Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 20

June 15, 2012

A peek at Mary Dyer's handwriting

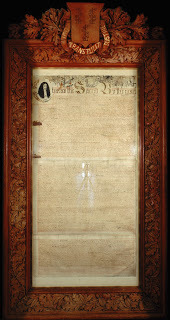

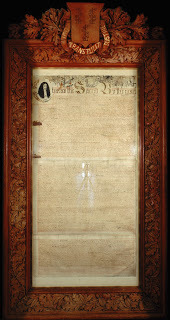

Transcript below of the fragmentary image of Mary Dyer's letter to the Boston court, 26 October 1659.

Transcript below of the fragmentary image of Mary Dyer's letter to the Boston court, 26 October 1659. (I'm still figuring out the words that fit in the blanks I left.)

From mary dire to ye generall court now this present 26thday of ye 8 mo 59 assembled in ye towne of boston in new Ingland greetings of grace mercy and peace to every soul yt doth well: tribulation anguish and wrath to ____ doth excell Whereas its said by many of you yt I ame guilty of mine owne death by my coming as you cal it voluntarily to boston: I therefore declare unto every one yt hath an ease to hear: yt in ye fear peace and love of god I came and in _____ did and stil doth commit my soul and body to him as unto a faithful creator who for this very end hath profferred my my life until now through many trials and temptations having held out his royal scepter unto mee by which I have access into his presence and have found such favoure in his sight as to offer up my life freely for his truth and peoples sakes: whom ye _____ hath moved you again...

Yes, I have the scan of the entire document, front and back, which I'll be transcribing in my historical novel (in process of being written). I may use the image as a background in the book's cover image, so it's best not to blast it all over the internet at this time.

Mary came to the end of the large sheet of textured paper, and turned it over to write six more lines, the ghost image you see behind the words in the middle of this fragment. On the right vertical edge of the paper are water stains which smeared the ink. Perhaps it was raining when the messenger carried her letter from the jail to the Massachusetts General Court, presided over by Governor John Endecott. The letter was folded at some point, and the paper has flaked away at some folds and edges, but for the most part, it's legible, even after more than 350 years!

Published on June 15, 2012 17:02

May 17, 2012

William Dyer and the Anglo-Dutch war

The First Dutch War,

The First Dutch War,by Abraham Willaerts (Dutch painter)

© Christy K Robinson

On 17 May 1653, William Dyer, along with newly-elected Governor John Sanford and Nicholas Easton, formed an admiralty court to attend to Rhode Island colony’s part of all prizes secured in the war against the Dutch. “Prizes” were Dutch ships and their cargo, Dutch trading posts or farms encroaching on what the English colonists considered their chartered territory, or even Dutch trade goods from the East Indies carried by English, American, French, or Spanish ships. This taking of prizes, or privateering, was a powerful and lucrative business. It was a license to be a pirate in the employ of a government. The privateer shared a percentage of the prize with the employer, along with the advantage to the authorizing government of valuable ships which could be fitted for their own navy.

The first Anglo-Dutch war (there were three of them) was all about trade with foreign ports, following England's Navigation Act.

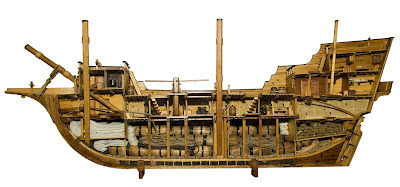

Cross-section of a 17th-century merchantman,

Cross-section of a 17th-century merchantman, the sort that Dyer and Hull may have commanded--or taken as prize.

It's certainly a ship that plied the West Indies, America's east coast,

the Mediterranean, and the English Channel.

Captain William Dyerwas at this time Rhode Island attorney general, and had already been commissioned by England’s Council of State in early October 1652. His orders were to “raise such forts and otherwise arm and strengthen your Colony, for defending yourselves against the Dutch, or other enemies of this Commonwealth, or for offending them, as you shall think necessary; and also to take and seize all such Dutch ships and vessels at sea, or as shall come into any of your harbors, or within your power, taking care that such account be given to the State as is usual in the like cases. And, to that end, you are to appoint one or more persons to attend the care of that business; and we conceive the bearer hereof, Mr. William Dyer, is a fit man to be employed therein; and you are to give account of your proceeding to the Parliament or Council.”

It was signed by James Harington, president of the Council of State that month, and John Thurloe, clerk of the council—and spymaster for the Commonwealth of England.

(Did Thurloe, who had a network of spies in the West Indies, America, and Europe, expect spy reports from William Dyer? Hmmm… Interesting thought, because William appears to have been a royalist, not a fan of the puritan parliament.)

With very similar language to the orders from England, Rhode Island’s legislature commissioned him commander-in-chief upon the sea on May 27.

[I modernized the antiquated spelling for your ease of reading.]

This certifies whom it may concern that whereas we the free inhabitants of Providence Plantations having received authority and power from the Right honorable Council of State by authority of parliament to do something ourselves from the Dutch, the enemy of the Commonwealth of England, as also to assist them as we shall think necessary as also to seize all Dutch vessels or ships that shall come within our harbors within our power.

And whereas by true information and great complaint of the severe condition of many of our cantonments of English natives living on Long Island are subjected to the double sovereigns of the Dutch province at the manors there and the desperate hazard they are subjected to by the bloody plotting of the governor and all, show who are decided and declared to have demand in and any ways of the Indians by bribes and promises to set off and destroy the English natives in those places by which exposure one cantonment is put in trouble as quite desperate hazards and in continual fear to be set off and murdered unless some speedy and defensible remedy is so provided.

These present we consider and as all neighbors by our general assembly met the 19th of May 1653. It was agreed and is to remind by the said assembly that it was necessary and for our own defense (where if the English there should be attacked or set off) we could not long enjoy our stations chosen as before we have thought it necessary both to defend our selves and so sustain them to give.

And we hereby give by virtue of our authority provided us before full power and authority to Capt. William Dyer and Capt. John Underhill to take all Dutch ships and vessels as shall come into their power and so to defend themselves from the Dutch and all enemies of the Commonwealth of England. And do further think it necessary that they offend the Dutch, offer all inducements also to take them by indulgence, and to prevent the effusion of blood, provided also that no violence be given nor no detriment sustained to them it shall submit to the Commonwealth of England which being which authority though thus may offend them at the Expedition of Capt. William Dyer and Capt. John Underhill who by devise and counsel of three councilors one of which councilors dissenting have power to bring the same to conformity to the Commonwealth of England provided that the states so provide and all vessels taken be brought into the harbor at Newport and according to the law to show before and states that further provided also that these seized and authorized by us do give account of their proceedings to the said Court and assistants of the Colony and accordingly provide further instructions to order their assigns by the President and assistants aforesaid.

It is further provided that Capt. John Underhill is constituted Commander-in-Chief upon the lands and Captain William Dyer Commander-in-Chief at the sea, yet to join in counsel to be assisted both to other for the preparings of the several seizures for the honor of ye Commonwealth of England in which they are employed.Given under the Seal of the Colony of Providence Plantations this the present 27th of May, 1653. Per me, Will Lytherland, General Recorder.

Captain John Underhill was magistrate of Flushing, New Netherland (later called NewYork), a Dutch territory, from 1651-1653, all the time he was commander-in-chief upon the land for the English citizens of New England. He was married to a Dutch woman, Helena; her mother, also Dutch, resided with their family. Underhill was a military officer-for-hire from his training days in 1620s Netherlands, to his career with the English colonists in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and on Long Island. After some run-ins with the Massachusetts courts, they refused his compensation and he couldn’t find work, so he sailed back to England, where he also could not find the right fit. So he offered his services to the Dutch of Long Island and Manhattan for some years. Now, with a conflict brewing in the English Channel, he was back in the employ of the English, andhe was knowledgeable about the disputed territories, defenses, finances, and weaknesses of the Dutch in New England.

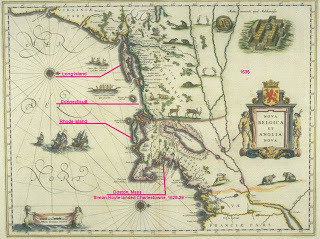

This 1635 map considers Connecticut and Long Island to be

This 1635 map considers Connecticut and Long Island to be "New Netherland" for settlement and trading purposes.

In other words--the Dutch claimed it as their own.

A commission was given May 27, 1653, to Captains Dyer and Underhill to “go against the Dutch” in the first Anglo-Dutch war of 1652-54. The war had been fought, on and off, in the English Channel since the year before, and it was destined to end in treaty early in 1654. But during the second half of 1653, with the unscrupulous Captain Edward Hull authorized to prey on Dutch vessels in Long Island Sound, the Anglo-Dutch war was fought between the shores of Long Island and Connecticut. The two commanders were ordered to do their best to prevent violence and bloodshed if possible.

According to Rhode Island records, Dyer’s and Underhill’s first target was the House of Good Hope, a Dutch trading post on the south side of the tributary to the Connecticut River at Hartford. (Another blog post, another time!)

Here’s something to get you started, though: This is the location of House of Good Hope: south bank of Little River (now the underground Park River) where it met the Connecticut River. The street called Huishope memorializes the grounds of the trading post. The smaller river was diverted and covered over, and is now covered by Park Street and buildings. Photo: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f8/Park_River_Conduit.JPG

Paddling Hartford’s Park River (formerly Hog River, formerly Little River), article:http://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/31/nyregion/paddling-hartford-s-scenic-sewer-abused-underground-river-up-close-noxious.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Published on May 17, 2012 18:03

May 7, 2012

Cures for what ails ye

© Christy K. Robinson

Woman bathing in a stream,

Woman bathing in a stream, RembrandtSome unpleasant medical and physical conditions, it seems, have been around forever. Many of them are preventable with hygiene practices, or we’ve learned which products we can purchase at the supermarket or corner store like Walgreens, CVS, or Boots.

Twelve generations ago, all sorts of quack remedies were available to treat conditions we generally avoid by bathing, cleaning our teeth, eating wholesome, fresh foods, and drinking pure water. Immersion bathing probably wasn’t very common for city dwellers, and without many changes of clothing, the aromas must have been quite ripe at any time of the year.

Because of the cost of consulting a physician, many with minor ailments benefited from the skills of an herbalist-healer or midwife. Depending on the spiritual climate, though, healers were sometimes accused as witches.

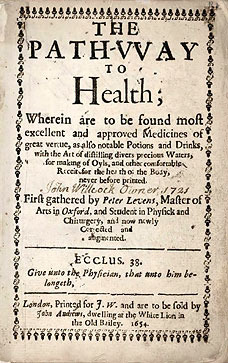

An array of potions and lotions that were considered cures for baldness, body odor, halitosis, and flatulence is chronicled in The Path-Way To Health. The book's subtitle reads: "Wherein are to be found most excellent and approved Medicines of great vertue, as also notable Potions and Drinks, with the Art of distilling divers precious Waters, for making of Oyls, and other comfortable Receit for the health of the body, never before printed."

This edition says 1654, but the original

This edition says 1654, but the original edition would have been 1597.

These libraries carry the 228-page book.

The book’s intended market was the physician, but probably also the apothecary who supplied the ingredients: snail’s blood, arsenic, lye, bird eggshells, herbs, distilled and brewed alcohol, seeds, cats' dung, and oils.

The author, Peter Levens, a physician and surgeon, held an MA degree from Oxford University in England, as did Dr. John Clarke, the principal author of Rhode Island’s charters of liberties and a Baptist minister. (The Master’s degree would not have been in medicine. In Dr. Clarke’s case, it was in theology.) Dr. Clarke was a friend and neighbor of William and Mary Dyer in Portsmouth and Newport, Rhode Island, and was one month younger than William Dyer.

Peter Levens lived in the 16thcentury, obtaining his Bachelor’s degree at Oxford in 1556 (during Queen Mary’s bloody reign), his MA in 1559 (just after Elizabeth I ascended the throne), and then practicing medicine and teaching grammar school. The Path-Way to Health was published in 1596, 1608, 1632, 1644, 1654, and 1664. This medical journal was written in English at a time when all scholarly work was recorded in Latin. Levens believed that books written in unknown or difficult-to-understand languages hid knowledge from people, and those who hid such wisdom were guilty of “malice exceeding damnable and devillish.”

Dr. Clarke, who emigrated to Boston in 1637 and moved with the Hutchinsons and Dyers (and many others) to Rhode Island, returned to England from late 1652 to about 1664, where he was the Rhode Island agent or representative working for their interests, and where he practiced medicine in London. Three editions of Path-Way to Health were published during the times Dr. Clarke lived in England! It’s very likely that he would have known of, or possibly used, this journal. I wonder if he treated Newport families with these or other remedies from the book.

Visit of the Physician, by Gabriel Metsu, 1660s

Visit of the Physician, by Gabriel Metsu, 1660sSome of Path-Way’s suggested cures:

To cure baldness:Take the ashes of Culver-dung [chicken dung] in Lye [potassium salts from ashes], and wash the head therewith. Also, Walnut leaves beaten with Beares suet, restoreth the haire that is plucked away. Also, the leaves and middle rinde of an Oak sodden in water, and the head washed therewith, is very good for this purpose."

To take away haire in unwanted places: Take the shels of two Egges, beat them small, and stil them with a good fire, and with that water annoynt the place; or else take hard Cats dung, dry it and beat it to powder, and temper it with strong Vineger, then wash the place with the same, where you would have no haire to grow.Also, take the bloud of a Snaile without a shel, and it hindereth greatly the growing up of haire.Also, take Labdanum [a sticky brown resin], the gum of a Ivie tree, Emmets Eggs, Arsenick and Vineger; and binde it to the place where you wil have no haire to grow.Or boil Frankensence and Barrows grease into an ointment.

A remedy for louse nits: Smear the scalp with the gall of a Calfe.

Where nails have been rent from the flesh: A mixture of brimstone, arsnick and vinegar can ease pain.Take Wheat flower, and mingle the same with Honey, and lay it to the nails, and it wil help them.

For stinking breath:Wash the mouth out with water and vinegar, followed by a concoction of aniseed, mint and cloves sodden in wine.

For a stench under the armpits: First, pluck away the haires of the arme holes, and wash them with white Wine and rosewater that cassialigna has been sodden in, and use it three or four times.

To help break wind in the belly [flatulence]: Drink a mixture of cumin seeds, fennel seeds and aniseeds in wine three times a day.

For women with great bellies: Take an handful of Isop, a handful of Herb-grace, a handful of Arsmart, and seethe all these herbs in a quart of Ale til it come to a pint, then preserve the same in a glass, and give the woman so grived a quarter of a pint at once, first in the morning and last at night.

For Womens paps [breasts] that arte rancled and be ful of ache:Take Grounsel, and two times as much of Brouswort, and wash them both, and stamp them, and temper them with stale Ale, and straine it through a cloth, and give it to the Patient thereof first thing in the morning and last at night.

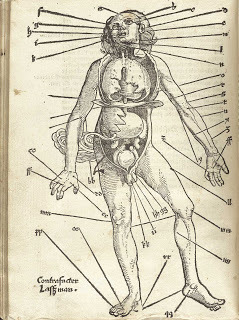

1517--Feldbuch diagram of blood-letting points.

1517--Feldbuch diagram of blood-letting points.Rules for Blood Letting: The vein above the thumb is good against all fevers. The vein between the thumb and the forefinger, let blood for the hot headache, for frenzy and madness of wit. Also be ye always well advised, and wary, that ye let no blood, nor open no vein, except the Moon be either in Aries, Cancer, the first half of Libra, the last half of Scorpio, or in Sagittarius, Aquarius, or Pisces.

Hmmm, I wonder if the snail minded being “bled” outside of those prescribed times!

Most of us, even the back-to-natural-remedies folks, vegans, PETA supporters, and just plain squeamish (that would be me), give thanks for antiperspirant, moisturizer, Rogaine, tweezers or wax, antiseptic, mild soap and minty shampoo, analgesic burn ointments, Gax-X, toothpaste and breath fresheners. Not to mention hot showers any time we wish!

Published on May 07, 2012 00:00

May 2, 2012

My Dearest Dust

Lady Katherine Dyer and the epitaph to her beloved husband

Hand-holding effigies of Katherine Mortimer and Thomas Beauchamp,

Hand-holding effigies of Katherine Mortimer and Thomas Beauchamp, Countess and Earl of Warwick, St. Mary's, Warwick.

Both died in 1369.

Guest post by Johan Winsser

In 1641 Lady Katherine Dyer erected in the church of St Denys in Colmworth, Bedfordshire, a large, ornate tomb to the memory of her beloved husband, Sir William Dyer, who died twenty years earlier at age 38. It is composed of prostrate statues of Sir William and Lady Katherine Dyer and below them, between the carved figures of Faith, Hope, and Charity, smaller statues of their seven surviving children and one grandchild, who died in infancy.

Inscribed on the tomb is the following remarkable epitaph.

If a large hart, joined with a noble mindeShewing true worth unto all good inclin’dIf faith in friendship, justice unto all,Leave such a memory as we may callHappy, thine is; then pious marble keepeHis just fame waking, though his lov’d dust sleepe.And though death can devoure all that hath breath,And monuments them selves have had a death,Nature shan't suffer this, to ruinate,Nor time demolish’t, nor an envious fate,Rais’d by a just hand, not vain glorious pride,Who'd be concealed, wer’t modesty to hideSuch an affection did so long surviveThe object of ’t; yet lov’d it as alive.And this greate blessing to his name doth giveTo make it by his tombe, and issue live.

My dearest dust, could not thy hasty dayAfford thy drowzy patience leave to stayOne hower longer: so that wee might eitherSate up, or gone to bedd together?But since thy finisht labor hath possestThy weary limbs with early rest,Enjoy it sweetly; and thy widowe bride

Shall soone repose her by thy slumbering side;Whose business, now, is only to prepareMy nightly dress, & call to prayer:Mine eyes wax heavy & the day grows old,The dew falls thick, my blood grows cold.Draw, draw the closed curtayns: & make roome:My deare, my dearest dust; I come, I come.

Sir William (1583-1621) was the eldest son of Sir Richard Dyer of nearby Great Staughton, Huntingdonshire, and therein closely related to the prominent West Country Dyers that included Sir James Dyer, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, and Sir Edward Dyer, the Elizabethan courtier and poet. Sir William was an active man who was once called to account for hunting deer in the king’s park and on another occasion was party to a melee in which a man was killed. He was heir to a substantial estate, but owing to the early death of his father and his own youthfulness, came into straightened times that required him to lease and sell off much to meet his obligations.

Sir William’s sister Anne married first the much older Sir Edward Carre of Sleaford, Lincolnshire, and second, Sir Henry Cromwell, cousin to the future Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. While the ancestry of Mary Dyer’s husband William and his possible relationship to Anne (Dyer, Carre) Cromwell remains unknown, it is notable that Sleaford is adjacent to Kirkby Laythorpe, where William was born, that William did very well on behalf of Rhode Island (and himself) when he appeared before Cromwell’s Council of State seeking a new charter for Rhode Island and a privateering commission; and that Anne’s son, Sir Robert Carre, was in 1664 sent to New England, New York, and Delaware to bring those colonies to the king’s account—and on whose coattails William and Mary’s son William, quickly rose to be customs collector and mayor of New York.

Lady Katherine was the daughter of John D’Oyley of Merton, Oxfordshire, and stepdaughter of Sir James Harrington of Exton, Rutland. “My Dearest Dust” is often attributed to Katherine Dyer, but uncertainly so. It is a beautiful and sophisticated composition, and no other works known to be by Katherine have been identified. Certainly she had the intelligence, family background, and likely private education to write it. But did she, or did she borrow or commission it? Its intimacy—and that she never remarried—argues that she wrote it herself.

Of curious note is the detailed dress of the four Dyer sons portrayed on the monument. Although Bedfordshire and the prominent West Country Dyer families were for the most part royalist, and two of the sons are dressed as such, the other two are dressed as roundheads (Puritan parliamentarians), thus suggesting a sad division in this family.

And how long did Lady Katherine have to wait to join her husband? Thirty-three years.

Read more: Photos of the memorial effigies http://www.colmworthhistory.org.uk/#/lady-dyers-poem/4535905977http://preferreading.blogspot.com/2012/04/sunday-poetry-lady-catherine-dyer.htmlhttp://www.ralphmag.org/DG/dyer.htmlEnglish Heritage report on St. Denys church of Colmworth http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42413&strquery=dyer&fb_source=message

***********

Johan Winsser has been researching and writing about Mary Dyer for many years. Some of his research is found on his DyerFarm website. Thank you, Johan, for your contributions to Dyer genealogy research, and to this Dyer blog.

Johan Winsser has been researching and writing about Mary Dyer for many years. Some of his research is found on his DyerFarm website. Thank you, Johan, for your contributions to Dyer genealogy research, and to this Dyer blog.

Published on May 02, 2012 21:26

April 27, 2012

Portrait of a loser, 1640 New England

© Christy K. Robinson

In June 1640, one James Sabire, who had been set in stocks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, moved to Boston. There, he probably demanded a divorce from his pregnant wife Barbara, of the Boston magistrates. He charged Barbara with being an adulteress, and denying him his rights in the marriage bed.

In June 1640, one James Sabire, who had been set in stocks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, moved to Boston. There, he probably demanded a divorce from his pregnant wife Barbara, of the Boston magistrates. He charged Barbara with being an adulteress, and denying him his rights in the marriage bed.

Barbara Sabire wrote to the governor and assistants of Rhode Island, asking for a character reference and witness to her husband's abuse and her stellar behavior, probably hoping not to be set in stocks at Boston--or hanged as an adulteress! It appears that she sheltered in the home of William and Anne Hutchinson for nine months, perhaps during her pregnancy and delivery.

The letter below was written by William Hutchinson, to his friend-turned-enemy, John Winthrop, who had just been replaced in the governor's seat by the severe and strict Thomas Dudley.

Not only does the letter describe the horrible behavior of James Sabire, but between the lines, we can read what kind of relationships were expected of godly men toward their wives: honor, protection, providence, love, tenderness, loyalty.

No matter how I search the internet with different spellings, word searches, Winthrop’s Journal, Winthrop Papers, Documentary History of Rhode Island, date searches, etc., I cannot find record of James and Barbara Sabire outside this letter. Did Barbara's baby live? Was James whipped, fined, or exiled? Was the court case dropped? Perhaps they emigrated back to England, as many did at this time, and got caught up in the Civil Wars. Maybe they moved to New Hampshire or Long Island.

But one thing is certain: there was no divorce in Rhode Island or Massachusetts. With the harsh Thomas Dudley in the chief seat of the magistrates' panel, we can hope that Mr. Sabire was punished according to his many unsavory deeds, beginning with a drying-out period in jail. But Mrs. Sabire was tied to her husband and master unless they were able to obtain a divorce in England (possible, but very unlikely), or Mr. Sabire died in his cups.

Related article: The scarlet letter, D: punishment for drunks in the 1600s http://bit.ly/I9OtZd

In June 1640, one James Sabire, who had been set in stocks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, moved to Boston. There, he probably demanded a divorce from his pregnant wife Barbara, of the Boston magistrates. He charged Barbara with being an adulteress, and denying him his rights in the marriage bed.

In June 1640, one James Sabire, who had been set in stocks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, moved to Boston. There, he probably demanded a divorce from his pregnant wife Barbara, of the Boston magistrates. He charged Barbara with being an adulteress, and denying him his rights in the marriage bed. Barbara Sabire wrote to the governor and assistants of Rhode Island, asking for a character reference and witness to her husband's abuse and her stellar behavior, probably hoping not to be set in stocks at Boston--or hanged as an adulteress! It appears that she sheltered in the home of William and Anne Hutchinson for nine months, perhaps during her pregnancy and delivery.

The letter below was written by William Hutchinson, to his friend-turned-enemy, John Winthrop, who had just been replaced in the governor's seat by the severe and strict Thomas Dudley.

Not only does the letter describe the horrible behavior of James Sabire, but between the lines, we can read what kind of relationships were expected of godly men toward their wives: honor, protection, providence, love, tenderness, loyalty.

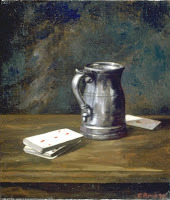

_____________________Wine glass, jelly glass, tumbler,

and wine bottles,

all probably made in England,

and a salt-glazed stoneware jug

came from colonial Boston’s

Three Cranes Tavern's privies.

The earliest privy,

dating from 1635 to 1662,

contained two wine glasses

possibly manufactured in 1590.

(Courtesy Norma Jane Langford

via Archaeology magazine)"To the Worshipful & much respected friend John Winthrop Esquire at his house in Boston

Right worshipful, We have lately received a letter from Barbara Sabire, the wife of James Sabire, now resident in Boston, with you, wherein we understand that he hath made complaint of her, if not false accusations laid against her, therefore we thought good to testify, being desired thereunto, what he confessed upon examination, before us whose names are here underwritten.

The ground of his examination was from some false reports he had raised up against his wife. We called them false because they proved so to be when they were inquired into, but not to trouble you with those: 1. A word or two of what he did confess, when the question was demanded of him, Did your wife deny unto you due benevolence, according to the rule of god or no? His answer was she did not, but she did and had given her body to him, this he confessed, & did clear her of that which now he condemns her for and this may evince it and prove it to be so. 2. He did here likewise report his wife was with child, which we understand he doth also deny unto your worships and that will also prove him to speak falsely if he shall say his wife did deny him marriage fellowship until he did come under your government: 3. This we must witness that his wife was not the ground or cause of his being set in the stocks, but for his disturbance of the peace of the place at unseasonable hours whereas people were in bed, and withal for his cursing and swearing and the like.

Again a word or two concerning his life when he was with us, It was scandalous and offensive to men, sinful before God; and towards his wife. Instead of putting honour upon her as the weaker vessel, he wanted [lacked] the natural affection of a reasonable creature, we also found him idleand indeed a very drone sucking up the honey of his wife’s labour, he taking no pains to provide for her, but spending one month after another without any labour at all, it may be some found one day in a month he did something being put upon it, being threatened by the government here; and indeed had he not been relieved by his wife and her friends where she did keep, he might have starved. Besides he is given very much to lying, drinking strong waters [whiskey], and towards his wife showing neither pity nor humanity, for indeed he could not keep from boys & servants, secret passages betwixt him and his wife [sexual demands she felt were immoral? rape?] about the marriage bed, and of those things there is more witnesses than us, and concerning her.

She lived with us about 3 quarters of a year, whose wife was unblameable before men for anything we know, being not able to charge her in her life & conversation but, beside her masters testimony, who best knows her is this, that she was a faithful, careful, & painful both servant & wife to his best observation, during the time with him.

Those things we being requested unto, we present unto your wise considerations hoping that by the mouth of 2 or 3 witnesses, the innocent will be acquitted, & the guilty rewarded according to his works; thus ceasing further to trouble you we take our leaves & rest.

Your worshipful Loving friends William Hutchinson [assistant governor]

William Baulston [treasurer]William Aspinwall [secretary]John Sanford [constable]

Portsmouth, Rhode Island, the 29th of 4th 1640 [29 June 1640]

Source: DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF RHODE ISLAND, p. 172

No matter how I search the internet with different spellings, word searches, Winthrop’s Journal, Winthrop Papers, Documentary History of Rhode Island, date searches, etc., I cannot find record of James and Barbara Sabire outside this letter. Did Barbara's baby live? Was James whipped, fined, or exiled? Was the court case dropped? Perhaps they emigrated back to England, as many did at this time, and got caught up in the Civil Wars. Maybe they moved to New Hampshire or Long Island.

But one thing is certain: there was no divorce in Rhode Island or Massachusetts. With the harsh Thomas Dudley in the chief seat of the magistrates' panel, we can hope that Mr. Sabire was punished according to his many unsavory deeds, beginning with a drying-out period in jail. But Mrs. Sabire was tied to her husband and master unless they were able to obtain a divorce in England (possible, but very unlikely), or Mr. Sabire died in his cups.

Related article: The scarlet letter, D: punishment for drunks in the 1600s http://bit.ly/I9OtZd

Published on April 27, 2012 16:06

April 24, 2012

The scarlet letter, D: punishment for drunks in the 1600s

© Christy K. Robinson

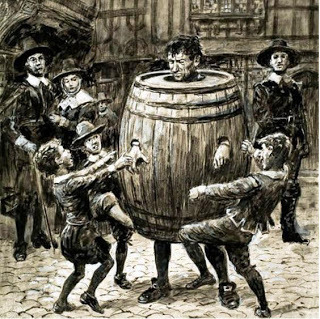

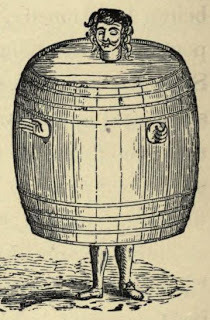

1655: An alcoholic is punished in a Drunkard's Cloak,

1655: An alcoholic is punished in a Drunkard's Cloak, what amounts to a pillory. Alcohol addiction is a neurological disease which affects body and mind, and is characterized by an uncontrolled consumption of alcohol. Treatment of alcoholism includes detoxification, counseling, support group participation, education, and sometimes medication. But treatment for addiction is a relatively-recent innovation. More commonly in history, “treatment” was punishment and shame.

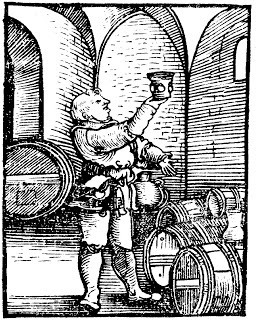

In 17th century England, nearly everyone drank alcoholic beverages, because water, especially in towns, was often contaminated and carried disease. Ale, beer, and cider were fermented and brewed at home, and had a relatively small alcohol content, about four percent. Wine was usually imported from warmer climates like France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. Everyone drank alcohol, including children and pregnant women, and it may have saved many lives from infectious disease, poisoning, and parasites that they’d have picked up from polluted water.

Whiskey had been distilled in Ireland and Scotland for several hundred years, and the English used it not only as a beverage, but as the base for some medications. They called it variously “strong waters,” or aqua vitae, the water of life. Governor John Winthrop and his eldest son, John Jr., dispensed medication based on aqua vitae.

In the homemaker’s guide, The English Housewife, published in 1615, a remedy for “heartsickness” (heart disease, or a broken heart?) was this: “Take rosemary and sage, of each a handful, and seethe them in white wine or strong ale, and then let the patient drink it lukewarm.”

In the homemaker’s guide, The English Housewife, published in 1615, a remedy for “heartsickness” (heart disease, or a broken heart?) was this: “Take rosemary and sage, of each a handful, and seethe them in white wine or strong ale, and then let the patient drink it lukewarm.” At the Great Migration beginning in 1630, the English brought their beverages and remedies with them to America. In the ships of the Winthrop fleet were 42 tuns of ale (about 10,000 gallons), an equal amount of wine, and 14 tuns of water (3,332 gallons). Fresh water went bad in the wooden casks on the 8-12 week crossings, so alcoholic drink was necessary for health—and not terrible for a feeling of well-being!

When the fleet arrived and people eventually settled in Boston and Cambridge, they remarked on the sweet water of the New World. “For the Countrey it is as well watered as any land under the Sunne, every family, or every two families having a spring of sweet waters betwixt them, which is farre different from the waters of England, being not so sharpe, but of a fatter substance, and of a more jetty colour; it is thought there can be no better water in the world, yet dare I not preferre it before good Beere, as some have done, but any man will choose it before bad Beere, Whey, or Buttermilke. Those that drinke it be as healthfull, fresh, and lustie, as they that drinke beere.” Source: William Wood, New-England’s Prospect As I’ve written elsewhere in this blog, alcohol use was widespread and considered beneficial to peoples’ health. The problems arose when drinking became drunkenness. The offenders were punished with time in stocks, disfellowship from the church, or whipping. Boston was the major port in New England, followed by Newport, Rhode Island, and drunk sailors often appear in court records and histories.

An outdoor tavern, probably in London

An outdoor tavern, probably in London (roof tiles instead of thatch).

There were a number of entries in Winthrop’s Journal about alcohol abuse and their various penalties, including instances of ships blowing up, sexual escapades (straight, gay, and bestial) being blamed on excessive drink, and this story of combining Sabbath-breaking with drunkenness (implying Divine justice for the drunkards): One Cowper of Pascataquack [near modern Portsmouth, New Hampshire], going to an island, upon the Lord's day, to fetch some sack [strong, dry, sweet, light-colored wine of the sherry family] to be drank at the great house, he and a boy, coming back in a canoe, (being both drunk,) were driven to sea and never heard of after.

Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop, in 1634, noted that Robert Cole (1598-1655), who had come to Massachusetts with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, “having been oft punished for drunkenness, was now ordered to wear a red D about his neck for a year.” Some literature professors suggest that this was the origin of the story written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter.

“Robert Cole was living in Roxbury, Massachusetts, when he petitioned to be made a "freeman" on 19 Oct 1630, and was granted that status by the General Court on 18 May 1631, along with 113 other men. He was disfranchised 4 Mar 1634, for a short time on account of his problem with drinking too much wine, when he was also ordered to wear a red letter "D" on his clothing for a year; however, his freeman status was reinstated about two months later on 14 May 1634, and the requirement to wear the letter ‘D’ was also revoked at that time.” Source:: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~bbunce77/ColeChart.html

The Bible instructed churches not to keep company with a member who was “a fornicator, or covetous, or an idolator, or a railer, or a drunkard, or an extortioner; with such an one not to eat.” 1 Cor. 5:18 KJV.

Robert Cole was actually treated with mercy, being removed from membership for a short time to clean up his act and be reinstated, compared to what he’d have endured as an alcoholic in his native England. There, he might have been sentenced to time in a torture device known as the drunkard’s cloak (see images), where he’d be driven around town (probably with sticks and stones), kicked, physically abused, spit or urinated on, and have feces flung at him. It's not a stretch to imagine that his tormenters would roll him down an incline in hopes that he'd crash.

In 1655, John Willis claimed that in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, “he hath seen men drove up and down the streets with a great tub or barrel opened in the sides, with a hole in one end to put through their heads, and so cover their shoulders and bodies, down to the small of their legs, and then close the same, called the newfangled cloak, and so make them march to the view of all beholders; and this is their punishments for drunkards and the like.”

In 1655, John Willis claimed that in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, “he hath seen men drove up and down the streets with a great tub or barrel opened in the sides, with a hole in one end to put through their heads, and so cover their shoulders and bodies, down to the small of their legs, and then close the same, called the newfangled cloak, and so make them march to the view of all beholders; and this is their punishments for drunkards and the like.”Obviously to us in the 21st century, the drunkard’s cloak was cruel and inhumane. In previous centuries, even as recently as 150 years ago in America, alcoholics were not treated for their disease, but punished in the hope that the persecution would be a deterrent to future antisocial behavior. Alcoholics have also been held up for ridicule in TV shows which depicted chronic drunks as bewildered fools who would sleep it off or be cured by drinking enough coffee. More likely, chronic alcohol abusers are prone to commit domestic violence, sexual abuse, and destroying lives on the road, while plagued with the most serious of health and mental problems of their own.

Perhaps we should think more about sweet spring water than an excess of alcoholic beverages. Those that drinke it be as healthfull, fresh, and lustie, as they that drinke beere.

Perhaps we should think more about sweet spring water than an excess of alcoholic beverages. Those that drinke it be as healthfull, fresh, and lustie, as they that drinke beere.

Published on April 24, 2012 19:17

April 9, 2012

What music was on Mary Dyer's iPod?

© Christy K. Robinson

Woman With a Cittern,

Woman With a Cittern,

by Pieter van SlingelandWilliam Dyer was born in 1609, near the Lincolnshirefens, and Mary Barrett probably in 1611 in the London area. They would have heard folk musicperformed at fairs and at special occasions like wedding and holiday dances. Fiddlersplayed recreational music. William probably heard bawdy songs in taverns and ashe went about his apprenticeship in London.Mary, who seems to have been privately educated, may have had access to privateparties or even court events, and she would have heard sinfonias, dance suites,chorales, and perhaps a masque (a participatory operetta with a moral to thestory).

The instruments they'd have heard were flutes/recorders,drums, trumpets, the viol family, harps, guitars, lutes, bagpipes from Scotland and Ireland, and virginals (smallkeyboards similar to a harpsichord). Woman Seated at a Virginal,

Woman Seated at a Virginal,

by Jan VermeerIn English churches, there were organs, choirs, andsometimes string ensembles until the puritan restrictions on music in religiousmeetings. When, in May 1644, the puritan Parliament legalized the demolition ofsacred objects (crosses, stained glass, paintings, tapestries, saint images,etc.), they declared that 'all organs, and the frames or cases wherein theystand in all churches or chapels aforesaid, shall be taken away, and utterlydefaced, and none other hereafter set up in their places.'

Church musicIn New England, where the Dyers lived after 1635, there wereno church organs—organs being related to the hated Catholic mass, and drawingattention away from God and to the skills of the performer. At Sabbath meetingsof the Massachusetts Bay churches, they sangpsalms without musical accompaniment. Rev. John Cotton disapproved ofinstruments in worship. In 1640, three ministers published the first book inthe American colonies: a psalter that they approved for use in the churches of Massachusetts Bay. It was a text of psalms in rhyme,without notes because almost no one could read musical notation. In a shorttime, congregations forgot the tunes, and each singer sang in his or her ownkey, melody, and rhythm. (Perhaps something like a "Happy Birthday" cacophony today.)

Thomas Walter wrote at the end of the 17th century:"The tunes are now miserably tortured and twisted and quavered, in somechurches, into a medly of confused and disorderly voices. Our tunes are left tothe mercy of every unskillful throat to chop and alter, to twist and change...No two men in the Congregation quaver alike or together, it sounds in the earof a good judge like five hundred different tunes roared out at the same timewith perpetual interferings with one another." Source: Puritans at Play: Leisureand Recreation in Colonial New England, byBruce C. Daniels, p. 54.

James Franklin (Benjamin Franklin's older brother) wrote in1720s satire that he was "credibly informed that a certain gentlewomanmiscarried at the ungrateful and yelling noise of a deacon" whom Franklin described as a"procurer of abortions."

Viol da gamba, two lutes, and a pocket fiddleMusic as art and recreationThough church music was in a woeful state, colonial secularmusic flourished at celebrations of all sorts, including dances and festivals,and urban dwellers spent evenings "consorting" with their instruments,particularly violins and viols. The more highly-educated (ministers, teachers,merchants) had the larger, more expensive instruments like the viol da gamba(six-stringed, but similar in size to the four-stringed cello) or the virginal.Many households who valued music but had less money, used shoulder-held violinsor a cittern, a wire-stringed instrument between a banjo and a mandolin. Militarymen naturally favored the trumpet, fife, or drum.

Viol da gamba, two lutes, and a pocket fiddleMusic as art and recreationThough church music was in a woeful state, colonial secularmusic flourished at celebrations of all sorts, including dances and festivals,and urban dwellers spent evenings "consorting" with their instruments,particularly violins and viols. The more highly-educated (ministers, teachers,merchants) had the larger, more expensive instruments like the viol da gamba(six-stringed, but similar in size to the four-stringed cello) or the virginal.Many households who valued music but had less money, used shoulder-held violinsor a cittern, a wire-stringed instrument between a banjo and a mandolin. Militarymen naturally favored the trumpet, fife, or drum.

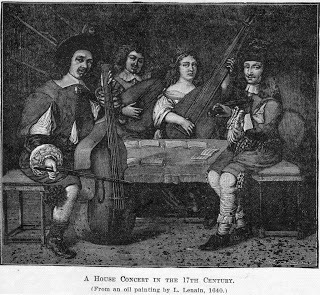

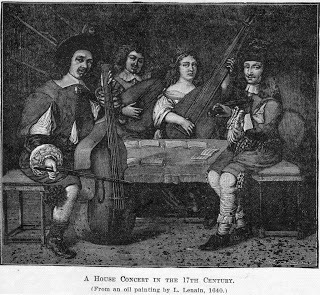

A Musical Party,

A Musical Party,

by Jacob van Velsen, 1631William and Mary Dyerwere educated, of the merchant class, and he was both a military man (captainof militia, and later, admiral) and a government official. They would haveattended and hosted parties, harvest festivals, weddings, house raisings andsewing bees, and the militia training days when potluck feasts and dancesoccurred. It's reasonable to expect that they at least danced and enjoyedmusical performances in homes, if not took part in music-making themselves.

*******************

Click the highlight for information on 17th centurymusical instruments in New France (French territories in North America).

The following links are videos of 17th century English music thatmight have touched the ears of the Dyers and their associates. Click thehighlighted titles to open a new tab in You Tube.

17thcentury English or Scottish folk tune The Water is Wide

Matthew Locke, Fantazie for two friendlyBasses

17thcentury English streetsong – TheCrost Couple, or A Good Misfortune.

17thcentury English song, The Bailiff's Daughter ofIslington – recorder and guitar

William Byrd, Earl ofOxford's March Brass quintet

Nicholas Lanier, MarkHow the Blushful Morn – soprano voice and lute

Nicholas Lanier, Love'sConstancy – soprano voice and lute

Try this early-17th century tune on your own at home!

Try this early-17th century tune on your own at home!

THIS is what comes of popular music!

THIS is what comes of popular music!

Every time she hit a certain pitch,

Every time she hit a certain pitch,

her bodice just dropped.

Woman With a Cittern,

Woman With a Cittern, by Pieter van SlingelandWilliam Dyer was born in 1609, near the Lincolnshirefens, and Mary Barrett probably in 1611 in the London area. They would have heard folk musicperformed at fairs and at special occasions like wedding and holiday dances. Fiddlersplayed recreational music. William probably heard bawdy songs in taverns and ashe went about his apprenticeship in London.Mary, who seems to have been privately educated, may have had access to privateparties or even court events, and she would have heard sinfonias, dance suites,chorales, and perhaps a masque (a participatory operetta with a moral to thestory).

The instruments they'd have heard were flutes/recorders,drums, trumpets, the viol family, harps, guitars, lutes, bagpipes from Scotland and Ireland, and virginals (smallkeyboards similar to a harpsichord).

Woman Seated at a Virginal,

Woman Seated at a Virginal,by Jan VermeerIn English churches, there were organs, choirs, andsometimes string ensembles until the puritan restrictions on music in religiousmeetings. When, in May 1644, the puritan Parliament legalized the demolition ofsacred objects (crosses, stained glass, paintings, tapestries, saint images,etc.), they declared that 'all organs, and the frames or cases wherein theystand in all churches or chapels aforesaid, shall be taken away, and utterlydefaced, and none other hereafter set up in their places.'

Church musicIn New England, where the Dyers lived after 1635, there wereno church organs—organs being related to the hated Catholic mass, and drawingattention away from God and to the skills of the performer. At Sabbath meetingsof the Massachusetts Bay churches, they sangpsalms without musical accompaniment. Rev. John Cotton disapproved ofinstruments in worship. In 1640, three ministers published the first book inthe American colonies: a psalter that they approved for use in the churches of Massachusetts Bay. It was a text of psalms in rhyme,without notes because almost no one could read musical notation. In a shorttime, congregations forgot the tunes, and each singer sang in his or her ownkey, melody, and rhythm. (Perhaps something like a "Happy Birthday" cacophony today.)

Thomas Walter wrote at the end of the 17th century:"The tunes are now miserably tortured and twisted and quavered, in somechurches, into a medly of confused and disorderly voices. Our tunes are left tothe mercy of every unskillful throat to chop and alter, to twist and change...No two men in the Congregation quaver alike or together, it sounds in the earof a good judge like five hundred different tunes roared out at the same timewith perpetual interferings with one another." Source: Puritans at Play: Leisureand Recreation in Colonial New England, byBruce C. Daniels, p. 54.

James Franklin (Benjamin Franklin's older brother) wrote in1720s satire that he was "credibly informed that a certain gentlewomanmiscarried at the ungrateful and yelling noise of a deacon" whom Franklin described as a"procurer of abortions."

Viol da gamba, two lutes, and a pocket fiddleMusic as art and recreationThough church music was in a woeful state, colonial secularmusic flourished at celebrations of all sorts, including dances and festivals,and urban dwellers spent evenings "consorting" with their instruments,particularly violins and viols. The more highly-educated (ministers, teachers,merchants) had the larger, more expensive instruments like the viol da gamba(six-stringed, but similar in size to the four-stringed cello) or the virginal.Many households who valued music but had less money, used shoulder-held violinsor a cittern, a wire-stringed instrument between a banjo and a mandolin. Militarymen naturally favored the trumpet, fife, or drum.

Viol da gamba, two lutes, and a pocket fiddleMusic as art and recreationThough church music was in a woeful state, colonial secularmusic flourished at celebrations of all sorts, including dances and festivals,and urban dwellers spent evenings "consorting" with their instruments,particularly violins and viols. The more highly-educated (ministers, teachers,merchants) had the larger, more expensive instruments like the viol da gamba(six-stringed, but similar in size to the four-stringed cello) or the virginal.Many households who valued music but had less money, used shoulder-held violinsor a cittern, a wire-stringed instrument between a banjo and a mandolin. Militarymen naturally favored the trumpet, fife, or drum.  A Musical Party,

A Musical Party, by Jacob van Velsen, 1631William and Mary Dyerwere educated, of the merchant class, and he was both a military man (captainof militia, and later, admiral) and a government official. They would haveattended and hosted parties, harvest festivals, weddings, house raisings andsewing bees, and the militia training days when potluck feasts and dancesoccurred. It's reasonable to expect that they at least danced and enjoyedmusical performances in homes, if not took part in music-making themselves.

*******************

Click the highlight for information on 17th centurymusical instruments in New France (French territories in North America).

The following links are videos of 17th century English music thatmight have touched the ears of the Dyers and their associates. Click thehighlighted titles to open a new tab in You Tube.

17thcentury English or Scottish folk tune The Water is Wide

Matthew Locke, Fantazie for two friendlyBasses

17thcentury English streetsong – TheCrost Couple, or A Good Misfortune.

17thcentury English song, The Bailiff's Daughter ofIslington – recorder and guitar

William Byrd, Earl ofOxford's March Brass quintet

Nicholas Lanier, MarkHow the Blushful Morn – soprano voice and lute

Nicholas Lanier, Love'sConstancy – soprano voice and lute

Try this early-17th century tune on your own at home!

Try this early-17th century tune on your own at home!  THIS is what comes of popular music!

THIS is what comes of popular music!

Every time she hit a certain pitch,

Every time she hit a certain pitch, her bodice just dropped.

Published on April 09, 2012 07:48

April 4, 2012

Silence is golden, but the bridle is ironic

© Christy K Robinson

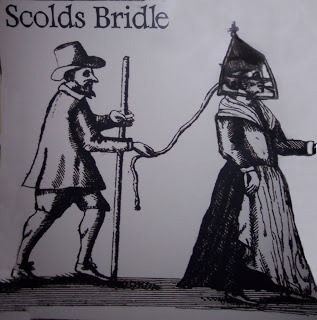

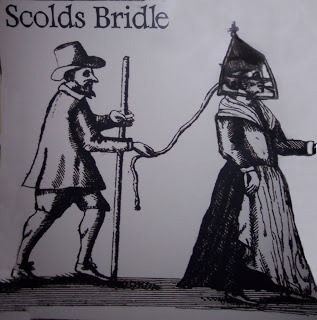

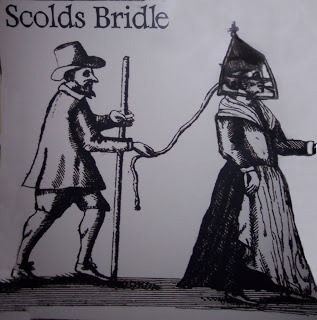

A woman with an iron bridle

A woman with an iron bridle

(called "branks" in Scotland)

on her head.

The 1650s were times of great upheaval in political andreligious circles. Englandhad still not recovered from the horrors of its Civil Wars of the previousdecade. Tens of thousands of men had died in the battles, from sickness more thanwounds; their women and children left at home were starving on the farms andmany left for the larger cities—where their fates were not much different in regard tostarvation and mortal illnesses. Several Christian sects, the Quakers foremostamong them, were heavily persecuted with excessive fines, imprisonment,beatings, brandings, and disfiguring ear removal.

William and Mary Dyersailed back to England inlate 1651 or early 1652, on business for Rhode Island. William went back to Rhode Island; Mary stayed in England. She stayed until early1657, and during those four years, became convicted of the principles of theFriends, who were "reproachfully" called Quakers. It's not known if Mary Dyer and Dorothy Waugh ever met in England, but they did meet in Rhode Island and Bostonin 1657 and 1658.

The young, unmarried Dorothy Waugh had been a housemaid in Preston Patrick, avillage in northwest Englandbetween Carlisle and Lancaster,and was a convert to the Quaker movement. There was a Friends group in thatout-of-the-way village: George Fox, during his journeysin the northwest, encountered a group of religious dissenters in the area knownas the Westmorland Seekers, and they were convicted of the gospel as Fox taughtthem. Fox allowed women to speak and preach. Most other schools of thought and theology were still blaming Eve for eating the forbidden fruit, and were holding her responsible for all humanity being driven from the Garden of Eden. Women were to keep silent not only in church, but in every public place.

Dorothy had little or no education, as only higher-statuswomen were taught to read and write. But she had enthusiasm and energy, and as some Quakers described it, the "fire and the hammer," andsoon she was giving her testimony and preaching the repentance of sinful ways,as she wandered England from London to Cornwall to Yorkshire.Quaker histories say that she was whipped and jailed numerous times all over England.Did she walk everywhere, travel with a group, or work her way through thecountryside for food and wagon rides?

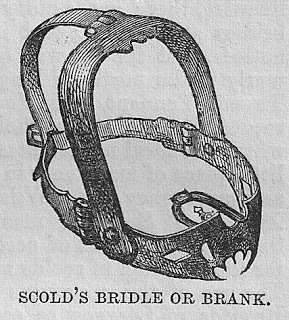

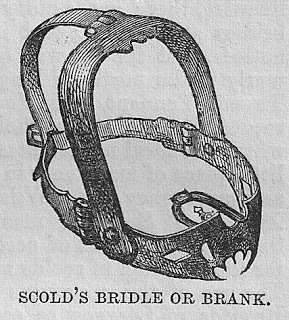

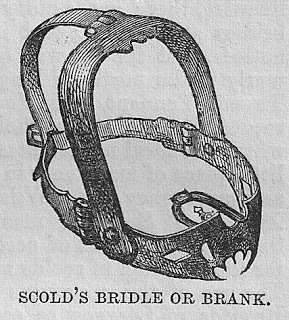

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branked." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whoscolded their husbands or otherwise disturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a tamed farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from beasts,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal.

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branked." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whoscolded their husbands or otherwise disturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a tamed farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from beasts,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal.

When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.

When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.

Dorothy had a taste of the bridle in 1655, in Carlisle, nearthe English border with Scotland.

"Dorothy Waugh, for declaring Truthin the Streets of Carlisle, and testifying against Sin and Wickedness, was,together with Anne Robinson who accompanied her, committed to Prison by theMayor, who ordered an Iron Instrument of Torture, called a Bridle, to be putupon the said Dorothy's Head, which they kept on about two Hours: And some timeafter having the like Iron Instrument put on both their Heads, which preventedtheir speaking to the People, they were publickly led through the Streets, andexposed to the Scorn and Derision of the Rabble, and then turned out of theCity." Source:AN ABSTRACT OF THE SUFFERINGS Of the PEOPLE call'd QUAKERS. FOR THE Testimony of a Good Conscience, Fromthe TIME of Their being first distinguished by that NAME, Taken from OriginalRecords, and other Authentick Accounts. VOLUME I. From the Year 1650 tothe Year 1660. LONDON: Printed and Sold by the Assigns of J.Sowle, at the Bible in George Yard, Lombard-street, 1733.

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)

The [Carlisle] Mayor 'was so violent & full of passion that he scarce askedme any more Questions, but called to one of his followers to bring thebridle as he called it to put upon me, and was to be on three houres, andthat which they called so was like a steele cap and my hattbeing violently pluckt off which was pinned to my head [so her scalp was probably torn when the hat was yanked off] whereby they taremy Clothes to put on their bridle as they called it, which was a stoneweight of Iron [about 14 pounds], & three barrs of Iron to come over my face, and apeece of it was put in my mouth, which was so unreasonable big a thing forthat place as cannot be well related, which was locked to my head, and soI stood their time with my hands bound behind me with the stone weight of Ironupon my head and the bitt in my mouth to keep me from speaking; And theMayor said he would make me an Example... Afterwards it was taken off andthey kept me in prison for a little season [hours? days? weeks?], and after a while the Mayorcame up againe and caused it to be put on againe, and sent me out of theCitty with it on, and gave me very vile and unsavoury words, which werenot fit to proceed out of any mans mouth, and charged the Officer to whipme out of the Towne.'

When Dorothy Waugh came to Rhode Islandand Massachusetts Bay in 1656, she partneredwith another missionary named Sarah Gibbons. They traveled on foot to Salem, Massachusetts,about 60 miles, and slept in the woods along the way, surviving a Marchblizzard and fierce winds. They were allowed to preach for two weeks without arrest; butdeciding it was too tame or too lax there, they went to Boston to "look your Bloody Laws in theFace." Once there, they were jailed for three days with no food, publiclywhipped (wherein they were stripped to the waist), starved for anotherthree days, then banished to Rhode Island.

When Dorothy Waugh came to Rhode Islandand Massachusetts Bay in 1656, she partneredwith another missionary named Sarah Gibbons. They traveled on foot to Salem, Massachusetts,about 60 miles, and slept in the woods along the way, surviving a Marchblizzard and fierce winds. They were allowed to preach for two weeks without arrest; butdeciding it was too tame or too lax there, they went to Boston to "look your Bloody Laws in theFace." Once there, they were jailed for three days with no food, publiclywhipped (wherein they were stripped to the waist), starved for anotherthree days, then banished to Rhode Island.

Dorothy and Sarah traveled to Hartford,Connecticut, were arrested and banished, and in1658, joined four other Quakers on a ship bound for Barbados, presumably to preachthere. But nothing is known of Dorothy after the late fall of 1658 in Barbados. Perhaps she married.Perhaps she died of illness or injury. Perhaps she was sold as a slave orbond servant. I suspect she died, because nothing else, including a barbarousbridle, could silence her when the cause of God was so precious.

A woman with an iron bridle

A woman with an iron bridle (called "branks" in Scotland)

on her head.

The 1650s were times of great upheaval in political andreligious circles. Englandhad still not recovered from the horrors of its Civil Wars of the previousdecade. Tens of thousands of men had died in the battles, from sickness more thanwounds; their women and children left at home were starving on the farms andmany left for the larger cities—where their fates were not much different in regard tostarvation and mortal illnesses. Several Christian sects, the Quakers foremostamong them, were heavily persecuted with excessive fines, imprisonment,beatings, brandings, and disfiguring ear removal.

William and Mary Dyersailed back to England inlate 1651 or early 1652, on business for Rhode Island. William went back to Rhode Island; Mary stayed in England. She stayed until early1657, and during those four years, became convicted of the principles of theFriends, who were "reproachfully" called Quakers. It's not known if Mary Dyer and Dorothy Waugh ever met in England, but they did meet in Rhode Island and Bostonin 1657 and 1658.

The young, unmarried Dorothy Waugh had been a housemaid in Preston Patrick, avillage in northwest Englandbetween Carlisle and Lancaster,and was a convert to the Quaker movement. There was a Friends group in thatout-of-the-way village: George Fox, during his journeysin the northwest, encountered a group of religious dissenters in the area knownas the Westmorland Seekers, and they were convicted of the gospel as Fox taughtthem. Fox allowed women to speak and preach. Most other schools of thought and theology were still blaming Eve for eating the forbidden fruit, and were holding her responsible for all humanity being driven from the Garden of Eden. Women were to keep silent not only in church, but in every public place.

Dorothy had little or no education, as only higher-statuswomen were taught to read and write. But she had enthusiasm and energy, and as some Quakers described it, the "fire and the hammer," andsoon she was giving her testimony and preaching the repentance of sinful ways,as she wandered England from London to Cornwall to Yorkshire.Quaker histories say that she was whipped and jailed numerous times all over England.Did she walk everywhere, travel with a group, or work her way through thecountryside for food and wagon rides?

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branked." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whoscolded their husbands or otherwise disturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a tamed farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from beasts,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal.

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branked." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whoscolded their husbands or otherwise disturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a tamed farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from beasts,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal. When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.

When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.Dorothy had a taste of the bridle in 1655, in Carlisle, nearthe English border with Scotland.

"Dorothy Waugh, for declaring Truthin the Streets of Carlisle, and testifying against Sin and Wickedness, was,together with Anne Robinson who accompanied her, committed to Prison by theMayor, who ordered an Iron Instrument of Torture, called a Bridle, to be putupon the said Dorothy's Head, which they kept on about two Hours: And some timeafter having the like Iron Instrument put on both their Heads, which preventedtheir speaking to the People, they were publickly led through the Streets, andexposed to the Scorn and Derision of the Rabble, and then turned out of theCity." Source:AN ABSTRACT OF THE SUFFERINGS Of the PEOPLE call'd QUAKERS. FOR THE Testimony of a Good Conscience, Fromthe TIME of Their being first distinguished by that NAME, Taken from OriginalRecords, and other Authentick Accounts. VOLUME I. From the Year 1650 tothe Year 1660. LONDON: Printed and Sold by the Assigns of J.Sowle, at the Bible in George Yard, Lombard-street, 1733.

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)The [Carlisle] Mayor 'was so violent & full of passion that he scarce askedme any more Questions, but called to one of his followers to bring thebridle as he called it to put upon me, and was to be on three houres, andthat which they called so was like a steele cap and my hattbeing violently pluckt off which was pinned to my head [so her scalp was probably torn when the hat was yanked off] whereby they taremy Clothes to put on their bridle as they called it, which was a stoneweight of Iron [about 14 pounds], & three barrs of Iron to come over my face, and apeece of it was put in my mouth, which was so unreasonable big a thing forthat place as cannot be well related, which was locked to my head, and soI stood their time with my hands bound behind me with the stone weight of Ironupon my head and the bitt in my mouth to keep me from speaking; And theMayor said he would make me an Example... Afterwards it was taken off andthey kept me in prison for a little season [hours? days? weeks?], and after a while the Mayorcame up againe and caused it to be put on againe, and sent me out of theCitty with it on, and gave me very vile and unsavoury words, which werenot fit to proceed out of any mans mouth, and charged the Officer to whipme out of the Towne.'

When Dorothy Waugh came to Rhode Islandand Massachusetts Bay in 1656, she partneredwith another missionary named Sarah Gibbons. They traveled on foot to Salem, Massachusetts,about 60 miles, and slept in the woods along the way, surviving a Marchblizzard and fierce winds. They were allowed to preach for two weeks without arrest; butdeciding it was too tame or too lax there, they went to Boston to "look your Bloody Laws in theFace." Once there, they were jailed for three days with no food, publiclywhipped (wherein they were stripped to the waist), starved for anotherthree days, then banished to Rhode Island.

When Dorothy Waugh came to Rhode Islandand Massachusetts Bay in 1656, she partneredwith another missionary named Sarah Gibbons. They traveled on foot to Salem, Massachusetts,about 60 miles, and slept in the woods along the way, surviving a Marchblizzard and fierce winds. They were allowed to preach for two weeks without arrest; butdeciding it was too tame or too lax there, they went to Boston to "look your Bloody Laws in theFace." Once there, they were jailed for three days with no food, publiclywhipped (wherein they were stripped to the waist), starved for anotherthree days, then banished to Rhode Island. Dorothy and Sarah traveled to Hartford,Connecticut, were arrested and banished, and in1658, joined four other Quakers on a ship bound for Barbados, presumably to preachthere. But nothing is known of Dorothy after the late fall of 1658 in Barbados. Perhaps she married.Perhaps she died of illness or injury. Perhaps she was sold as a slave orbond servant. I suspect she died, because nothing else, including a barbarousbridle, could silence her when the cause of God was so precious.

Published on April 04, 2012 01:03

Silence is gold, but the bridle is iron

© Christy K Robinson

The 1650s were times of great upheaval in political andreligious circles. Englandhad still not recovered from the horrors of its Civil Wars of the previousdecade. Thousands of men had died in the battles, from sickness more thanwounds; their women and children left at home were starving on the farms andmany left for the larger cities—where their fates were not much different in regard tostarvation and mortal illnesses. Several Christian sects, the Quakers foremostamong them, were heavily persecuted with excessive fines, imprisonment,beatings, brandings, and ear removal.

William and Mary Dyersailed back to England inlate 1651 or early 1652, on business for Rhode Island. William went back to Rhode Island; Mary stayed in England. She stayed until early1657, and during those four years, became convicted of the principles of theFriends. It's not known if Mary Dyer and Dorothy Waugh ever met in England, but they did meet in Rhode Island and Bostonin 1657 and 1658.

The young, unmarried Dorothy Waugh had been a housemaid in Preston Patrick, avillage in northwest Englandbetween Carlisle and Lancaster,and was a convert to the Quaker movement. There was a Friends group in thatout-of-the-way village: George Fox, during his journeysin the northwest, encountered a group of religious dissenters in the area knownas the Westmorland Seekers, and they were convicted of the gospel as Fox taughtthem. Fox allowed women to speak and preach, just like men: most other schools of thought were still blaming Eve for eating the forbidden fruit.

Dorothy had little or no education, as only higher-statuswomen were taught to read and write. But she had enthusiasm and energy, andsoon she was giving her testimony and preaching the repentance of sinful ways,as she wandered England, from London to Corwall to Yorkshire.Quaker histories say that she was whipped and jailed numerous times all over England.Did she walk everywhere, travel with a group, or work her way through thecountryside for food and wagon rides?

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branksed." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whodisturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from other animals,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal.

Not much is known of Dorothy's life outside of a fewincidents in England and New England, but she's famous for her description of whatit was like to be "bridled" or "branksed." A bridle was a metal cage that waslocked over a woman's head, with a bit (possibly spiked) pressing down on her tongue so shecouldn't speak. It had been invented in medieval times to punish women whodisturbed the social order, and it was meant to reduce a woman's status to thatof a farm animal. The ability to speak distinguishes humans from other animals,but with this apparatus, a woman was forced to be as silent ("dumb") as ananimal. When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.

When a woman was bridled, she was led about the town on achain and whipped, or secured to the village cross, and was then open to theabuse of refuse or dung thrown at her, or of people urinating on her. Theinfliction of a bridle may reveal more about the men who did it than about thewomen who endured it: the men were insecure in their power when women claimeddivine revelation, interpreted scripture, or preached. They believed that womenwho stepped out of their appointed place brought chaos and God's judgment.Dorothy had a taste of the bridle in 1655, in Carlisle, nearthe English border with Scotland.

Dorothy Waugh, for declaring Truthin the Streets of Carlisle, and testifying against Sin and Wickedness, was,together with Anne Robinson who accompanied her, committed to Prison by theMayor, who ordered an Iron Instrument of Torture, called a Bridle, to be putupon the said Dorothy's Head, which they kept on about two Hours: And some timeafter having the like Iron Instrument put on both their Heads, which preventedtheir speaking to the People, they were publickly led through the Streets, andexposed to the Scorn and Derision of the Rabble, and then turned out of theCity. Source:AN ABSTRACT OF THE SUFFERINGS Of the PEOPLE call'd QUAKERS. FOR THE Testimony of a Good Conscience, Fromthe TIME of Their being first distinguished by that NAME, Taken from OriginalRecords, and other Authentick Accounts. VOLUME I. From the Year 1650 tothe Year 1660. LONDON: Printed and Sold by the Assigns of J.Sowle, at the Bible in George Yard, Lombard-street, 1733.

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)

A year later, before Dorothy joined other Quakers on thetiny missionary ship, Woodhouse, onits voyage to New England to proselytize,Dorothy gave an account of her experience in a pamphlet anthology called The Lamb's Defence Against Lyes. (1656)The [Carlisle] Mayor 'was so violent & full of passion that he scarce askedme any more Questions, but called to one of his followers to bring thebridle as he called it to put upon me, and was to be on three houres, andthat which they called so was like a steele cap and my hattbeing violently pluckt off which was pinned to my head whereby they taremy Clothes to put on their bridle as they called it, which was a stoneweight of Iron, & three barrs of Iron to come over my face, and apeece of it was put in my mouth, which was so unreasonable big a thing forthat place as cannot be well related, which was locked to my head, and soI stood their time with my hands bound behind me with the stone weight of Ironupon my head and the bitt in my mouth to keep me from speaking; And theMayor said he would make me an Example... Afterwards it was taken off andthey kept me in prison for a little season, and after a while the Mayorcame up againe and caused it to be put on againe, and sent me out of theCitty with it on, and gave me very vile and unsavoury words, which werenot fit to proceed out of any mans mouth, and charged the Officer to whipme out of the Towne.'

When Dorothy Waugh came to Rhode Islandand Massachusetts Bay in 1656, she traveledwith a woman named Sarah Gibbons. They traveled on foot to Salem, Massachusetts,about 60 miles, and slept in the woods along the way, surviving a Marchblizzard. They were allowed to preach for two weeks without arrest; butdeciding it was too tame or too lax there, they went to Boston to "look your Bloody Laws in theFace." Once there, they were jailed for three days with no food, publiclywhipped (wherein they would be stripped to the waist), starved for anotherthree days, then banished to Rhode Island.