Top 10 Things You May Not Know About Mary Dyer

© Christy K. Robinson

17th-century painting of Catholic Spaniards

17th-century painting of Catholic Spaniards hanging Dutch Protestants. This is the type

of gallows used in Mary Dyer's time.Mary Dyer was hanged, but not for "being a Quaker." I know, that's what most of the genealogy websites—and Wikipedia, and countless opinions and feature articles say. But it's not true. Thanks to the Quaker missionaries from England, there were hundreds of Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) converts in New England in the late 1650s and early 1660s. They were subject to persecution and physical torture (imprisonment in wet or freezing jail cells, topless whipping for men and women, having ears notched or sliced off, tongues bored through, being dragged from town to town, put in stocks, fined heavily and/or their possessions confiscated, banished) because they represented anarchy to the church-state government formed by the Massachusetts Bay founders. It also happened in England, and for the same reason—fear of anarchy to established traditions and government. Not one Quaker was hanged for religious beliefs or "being a Quaker," but because they were intentionally disobedient to anti-Quaker laws.You can see by Mary's letters to the Massachusetts court that she was ready for heaven, that she was appalled at their cruelty and wickedness, and that she chose to die. [image error] Martin Luther King Jr. and Ghandi

also practiced civil disobedience

to change the world.Mary Dyer committed civil disobedience. The four who were hanged, including Mary Dyer, actually chose to die, rather than agree to permanent exile from Massachusetts and their preaching and religious support there. They were given the opportunity to leave—and live—and chose instead to take a stand for liberty of conscience in the hope that their deaths would be so shocking that the persecution would end. They were hanged for civil disobedience. Mary Dyer's letters to the Boston magistrates show that she was opposed to their "bloody" laws of religious intolerance and persecution, and that she rejected their conditional offer of release.

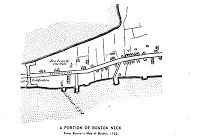

The strip of land that

The strip of land that connected Boston to the mainland.

The gallows were just outside

the fortification wall at the left.Not hanged on Boston Common. Nearly all accounts of Mary's and other "criminal" hangings say they were hanged on an elm tree on Boston Common, and their bodies were buried in a common grave (of Indians, thieves, paupers, etc.) now lost. This belief started more than a hundred years after Mary's 1660 execution. In M.J. Canavan's speech to the Boston Historical Society, published in the book, Where were the Quakers hanged in Boston? , he makes the case that executions in the 17th century were made just outside the fortification on Boston Neck, the isthmus that connected the Shawmut Peninsula to the Massachusetts mainland. It was about a mile's walk from the prison.Mary was educated, intelligent, well-bred, beautiful, wealthy. She was no timid wallflower. She was described as a woman "of no mean extract or parentage, of an estate pretty plentiful, of a comely stature and countenance, of a piercing knowledge in many things, of a wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse, so fit for great affairs, that she wanted [lacked] nothing that was manly, except only name and sex." Another writer said of Mary: "a Comely Grave Woman, and of a goodly Personage, and one of a good report, having a Husband of an Estate, fearing the Lord, and a Mother of Children." Mother of a "monster." Mary Dyer's third pregnancy ended in the premature stillbirth of a girl with anencephaly (having only a brain stem) and spina bifida deformities. Six months after it was buried, Governor John Winthrop ordered the exhumation and examination of the baby, calling it a monster, and proof of God's judgment on Mary's heresy to the puritan beliefs and lifestyle. In 1644, he published a book in England about Anne Hutchinson's heresy trial that described the Dyer baby's appearance. In the mid-1600s, there was an urban legend that women who preached, or even listened to a woman preacher, bore monsters. Mary bore eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood.

Mary Dyer was co-founder of two American cities. Many people believe that Mary Dyer was a Pilgrim who came to America on the Mayflower. Untrue! Stop it now! Though her name is not on the documents because as a woman she wasn't a "freeman" who could vote, Mary came to Boston in 1635 with her husband. In 1638, she was a pioneer who walked from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband, small child, and other families connected with Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Mary's husband William Dyer signed the Portsmouth Compact that united the founders of the new colony, and he was among the purchasers of Rhode Island from the Indian sachems. One year later, Mary and William and others established the town of Newport, Rhode Island. Mary's husband was a fishmonger, milliner, surveyor, farmer, politician, militia captain, sea captain, and trader. William's apprenticeship in London had been to the professional guild, the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, which had London mayors and council members among its alumni, but his first profession was milliner. A milliner was not a maker of fancy hats and bonnets, but a supplier of leather goods and accessories from Milan, Italy (Milan-er). William's apprenticeship in foreign trade, imports and exports, and merchandizing was probably the equivalent of a modern Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree! And it's probable that like a university student or intern, in his nine years of apprenticeship, William would have learned much about commercial fishing and its inspections and regulation. In New England, he was quickly put to work as a surveyor, trader, and administrator.Mary was married to a man of "firsts." Mary's husband, Captain William Dyer, was the first Secretary of State of Rhode Island, first Attorney General of Rhode Island (1650), and first Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England (1652-53). He was also commissioned as an admiral, by Sir Henry Vane in England.

Mary Dyer was co-founder of two American cities. Many people believe that Mary Dyer was a Pilgrim who came to America on the Mayflower. Untrue! Stop it now! Though her name is not on the documents because as a woman she wasn't a "freeman" who could vote, Mary came to Boston in 1635 with her husband. In 1638, she was a pioneer who walked from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband, small child, and other families connected with Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Mary's husband William Dyer signed the Portsmouth Compact that united the founders of the new colony, and he was among the purchasers of Rhode Island from the Indian sachems. One year later, Mary and William and others established the town of Newport, Rhode Island. Mary's husband was a fishmonger, milliner, surveyor, farmer, politician, militia captain, sea captain, and trader. William's apprenticeship in London had been to the professional guild, the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, which had London mayors and council members among its alumni, but his first profession was milliner. A milliner was not a maker of fancy hats and bonnets, but a supplier of leather goods and accessories from Milan, Italy (Milan-er). William's apprenticeship in foreign trade, imports and exports, and merchandizing was probably the equivalent of a modern Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree! And it's probable that like a university student or intern, in his nine years of apprenticeship, William would have learned much about commercial fishing and its inspections and regulation. In New England, he was quickly put to work as a surveyor, trader, and administrator.Mary was married to a man of "firsts." Mary's husband, Captain William Dyer, was the first Secretary of State of Rhode Island, first Attorney General of Rhode Island (1650), and first Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England (1652-53). He was also commissioned as an admiral, by Sir Henry Vane in England.

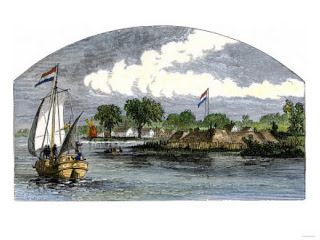

A Dutch trading ship at a fort near Hartford, Connecticut.Mary's husband was a privateer—a pirate with a license. Captain William Dyer (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas) and Captain John Underhill (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land) were commissioned, during the Anglo-Dutch War in 1652-53, to harass the Dutch traders and settlers occupying what's now known as Long Island, Manhattan, New York, and Connecticut. William's job was to take "prizes" of ships and their cargos, and split the profits with the United Colonies. As a result of the Dyer/Underhill ship and farm "takeovers" (or at least the imminent threat of them), the Dutch governor ordered a defensive wall built across the southern part of Manhattan Island. The wagon road that ran alongside the wooden palisade was called Wall Street. Wall Street is still the domain of raiders, 350 years later… Mary was staying in England during the time William performed these controversial acts.

A Dutch trading ship at a fort near Hartford, Connecticut.Mary's husband was a privateer—a pirate with a license. Captain William Dyer (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas) and Captain John Underhill (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land) were commissioned, during the Anglo-Dutch War in 1652-53, to harass the Dutch traders and settlers occupying what's now known as Long Island, Manhattan, New York, and Connecticut. William's job was to take "prizes" of ships and their cargos, and split the profits with the United Colonies. As a result of the Dyer/Underhill ship and farm "takeovers" (or at least the imminent threat of them), the Dutch governor ordered a defensive wall built across the southern part of Manhattan Island. The wagon road that ran alongside the wooden palisade was called Wall Street. Wall Street is still the domain of raiders, 350 years later… Mary was staying in England during the time William performed these controversial acts.

Mary Dyer heard God's voice. In her twenties, Mary was a close friend and student of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, who claimed divine revelation and visions, and by doing so, incited the fury of the Boston Puritan leaders who believed that God only communicated in that way with men. Massachusetts Gov. John Winthrop said that Anne and Mary were "much addicted to revelations." When Mary studied Quaker beliefs in the 1650s, she learned that they called divine revelation the Inner Light. Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians today would recognize it as the Holy Spirit speaking to one's heart. Secular people would term it a conscience. To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary andWilliam Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page, and follow http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

Mary Dyer heard God's voice. In her twenties, Mary was a close friend and student of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, who claimed divine revelation and visions, and by doing so, incited the fury of the Boston Puritan leaders who believed that God only communicated in that way with men. Massachusetts Gov. John Winthrop said that Anne and Mary were "much addicted to revelations." When Mary studied Quaker beliefs in the 1650s, she learned that they called divine revelation the Inner Light. Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians today would recognize it as the Holy Spirit speaking to one's heart. Secular people would term it a conscience. To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary andWilliam Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page, and follow http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

Published on December 01, 2011 23:00

No comments have been added yet.