Karen Lynn Allen's Blog, page 8

August 28, 2012

A Tale of Five Cities--Fascinating, Evolving Berlin

(This is the second of a five-part series. Part one is Charming,Livable Amsterdam.)

Brandenburg Gate November 1989Berlin is a paradox. Full of history and charm, it is neither quaint nor charming in a conventional sense. It has buildings that look centuries old but, in fact, were rebuilt nearly stone for stone only a few decades ago. It is the capital of a country with one of the greatest economies in the world, and yet its streets and its people often look a disheveled, funky, scraping by. Like Rome, Berlin has so many resonating layers of history they burst through each other to claim one’s attention. There is Prussian old Berlin of the Kaisers and ambitious Bismark. There is chaotic Berlin of the twenties, rising fascist Berlin of the 30’s. There is insane warmongering Nazi Berlin, and defeated, bombed-into-rubble post-war Berlin. Occupied Berlin turns into Cold War Berlin that segues into wall-divided Berlin. This crystallizes into a Berlin dominated by the paranoid, scary, and in some ways wildly funny DDR, a James Bond villain government if there ever was one. And then we have heroic Berlin, Berlin of the wall-tearer-downers, Berlin of the jubilant Brandenburg Gate. Berlin reclaiming itself; a Berlin of unity, healing, restoration. And today a Berlin that is still reimagining and reinventing itself, greening itself, all the while shouldering its role as uber-serious fiscal leader of Europe.

Brandenburg Gate November 1989Berlin is a paradox. Full of history and charm, it is neither quaint nor charming in a conventional sense. It has buildings that look centuries old but, in fact, were rebuilt nearly stone for stone only a few decades ago. It is the capital of a country with one of the greatest economies in the world, and yet its streets and its people often look a disheveled, funky, scraping by. Like Rome, Berlin has so many resonating layers of history they burst through each other to claim one’s attention. There is Prussian old Berlin of the Kaisers and ambitious Bismark. There is chaotic Berlin of the twenties, rising fascist Berlin of the 30’s. There is insane warmongering Nazi Berlin, and defeated, bombed-into-rubble post-war Berlin. Occupied Berlin turns into Cold War Berlin that segues into wall-divided Berlin. This crystallizes into a Berlin dominated by the paranoid, scary, and in some ways wildly funny DDR, a James Bond villain government if there ever was one. And then we have heroic Berlin, Berlin of the wall-tearer-downers, Berlin of the jubilant Brandenburg Gate. Berlin reclaiming itself; a Berlin of unity, healing, restoration. And today a Berlin that is still reimagining and reinventing itself, greening itself, all the while shouldering its role as uber-serious fiscal leader of Europe. See the gleamFor one of my daughters, Berlin was her favorite of the cities we visited; for the other, it was the least. One found it modern, bustling, vibrant, its history exciting, its people lively and creative. The other found it grey, drab, gritty, its scale too big, its history too sad, its architecture too prone towards brutalism. More than anything, Berlin feels unfinished, a work in progress. The former eastern half is still being rebuilt, upgraded, repaired, a massive effort and investment. From the top of the Berlin Cathedral we could see an absolutely ridiculous number of construction cranes in operation. The banks of the Spree River host gleaming new government buildings, some with stunning architecture, most with extensive glass walls so that even major politicians can be seen lunching and conversing. (The walk along the Spree in and among these buildings is absolutely lovely.) A repaired and restored Reichstag boasts an elegant new glass cupola from which the public can gaze down at their government at work. (In theory all this glass is a symbol of the German government’s commitment to transparency.) The scale of it all, the sense that the German people are finding their stride, taking control of their destiny and finally putting their country back together the way they want it is impressive. This is not a country so divided by political dysfunction that nothing gets done. Things are happening here.

See the gleamFor one of my daughters, Berlin was her favorite of the cities we visited; for the other, it was the least. One found it modern, bustling, vibrant, its history exciting, its people lively and creative. The other found it grey, drab, gritty, its scale too big, its history too sad, its architecture too prone towards brutalism. More than anything, Berlin feels unfinished, a work in progress. The former eastern half is still being rebuilt, upgraded, repaired, a massive effort and investment. From the top of the Berlin Cathedral we could see an absolutely ridiculous number of construction cranes in operation. The banks of the Spree River host gleaming new government buildings, some with stunning architecture, most with extensive glass walls so that even major politicians can be seen lunching and conversing. (The walk along the Spree in and among these buildings is absolutely lovely.) A repaired and restored Reichstag boasts an elegant new glass cupola from which the public can gaze down at their government at work. (In theory all this glass is a symbol of the German government’s commitment to transparency.) The scale of it all, the sense that the German people are finding their stride, taking control of their destiny and finally putting their country back together the way they want it is impressive. This is not a country so divided by political dysfunction that nothing gets done. Things are happening here.But let’s back up to our entry into the land of Beethoven, sauerkraut and Euro Cup mania. Even though trains leave from Amsterdam to Berlin every other hour, our train was packed! I was very glad I reserved seats for the five of us or not only we would have been spread out among cars, we might not have had seats at all. (One Japanese tourist stood in the aisle of our car well over an hour to her destination.) The train was comfortable, but the food available for sale was surprisingly lacking. Luckily we had some fruit with us and a round of Dutch cheese. (This cheese saw us through three separate train trips.) Our train wasn’t one of the high-speed, 196 mph versions that Europe boasts. It was a cheaper, medium-speed train, humming along at only 120 mph. Practically a snail.

See them everywhereAs we traversed Germany, I was impressed by the number of solar panels and wind turbines dotting the landscape. The solar was mostly on rooftops; the wind turbines peppered farmland. Though there were some wind turbines in the Netherlands, they were nothing compared to Germany’s. Just the ones I could see from my train window made the great California wind farms of Altamont Pass and Montezuma Hills look small. Indeed, Germany now has 29 Gigawatts (GW) of wind energy capacity installed, compared to California’s 4.3 GW. The amount of solar PV we saw was also remarkable, especially given the latitude, considerably north of the US/Canadian border. But even with their northerly location, Germany has installed close to 25 Gigawatts (GW) of solar PV compared to California’s 1 GW of the same. Together wind plus solar meet about 16% of German electricity demand, so you can see the Germans are going after renewables pedal to the metal (so to speak.) It’s interesting to compare California to Germany since California has a little less than half of Germany’s population and a bit more than half of its GDP. California is first in the US for installed solar, and third for installed wind, behind only Texas and Iowa. But although California is ostensibly wealthier per capita than Germany, we’ve made only one-tenth the investment in solar and wind.

See them everywhereAs we traversed Germany, I was impressed by the number of solar panels and wind turbines dotting the landscape. The solar was mostly on rooftops; the wind turbines peppered farmland. Though there were some wind turbines in the Netherlands, they were nothing compared to Germany’s. Just the ones I could see from my train window made the great California wind farms of Altamont Pass and Montezuma Hills look small. Indeed, Germany now has 29 Gigawatts (GW) of wind energy capacity installed, compared to California’s 4.3 GW. The amount of solar PV we saw was also remarkable, especially given the latitude, considerably north of the US/Canadian border. But even with their northerly location, Germany has installed close to 25 Gigawatts (GW) of solar PV compared to California’s 1 GW of the same. Together wind plus solar meet about 16% of German electricity demand, so you can see the Germans are going after renewables pedal to the metal (so to speak.) It’s interesting to compare California to Germany since California has a little less than half of Germany’s population and a bit more than half of its GDP. California is first in the US for installed solar, and third for installed wind, behind only Texas and Iowa. But although California is ostensibly wealthier per capita than Germany, we’ve made only one-tenth the investment in solar and wind.  Our viewAfter crossing almost to the eastern edge of Germany, we finally arrived in Berlin. Our apartment was near Alexanderplatz, right in the center of the city. In fact, our apartment had a balcony terrace with a view of the crazy TV tower left over from the sixties (1969, to be exact) when so many cities felt the need to put up groovy, space-age constructs reaching toward the sky. Our apartment was five floors up and involved a lot of stairs. (Luckily, we are used to stairs where we live.) I found it pleasant to have an outdoor space, however small, to drink a cup of tea in the morning or look out at the city lights in the evening. It made the apartment more airy, more connected to the neighborhood and the natural world. I would go so far as to say having some small amount of outdoor living space is connected to psychological health.

Our viewAfter crossing almost to the eastern edge of Germany, we finally arrived in Berlin. Our apartment was near Alexanderplatz, right in the center of the city. In fact, our apartment had a balcony terrace with a view of the crazy TV tower left over from the sixties (1969, to be exact) when so many cities felt the need to put up groovy, space-age constructs reaching toward the sky. Our apartment was five floors up and involved a lot of stairs. (Luckily, we are used to stairs where we live.) I found it pleasant to have an outdoor space, however small, to drink a cup of tea in the morning or look out at the city lights in the evening. It made the apartment more airy, more connected to the neighborhood and the natural world. I would go so far as to say having some small amount of outdoor living space is connected to psychological health.Berlin is essentially a former East German city surrounded by former East German suburbs, and the fortunes of Berlin today reflect this historical fact. Even though Berlin is Germany’s capital and its largest city, its unemployment rate is double Germany’s as a whole and its GDP per capita is 16% less. This makes for a city that is both run-down and vibrant, energetic but also oddly tranquil.

Biking in BerlinOne source of tranquility for this dense city of 3.5 million was surprising: in the capital of one of the world’s greatest car manufacturers, there just weren’t a whole lot of cars on the streets. In fact, the rate of car ownership in Berlin is lower than every other major city in Europe. (Even lower than Amsterdam.) Half of all Berlin households do not own a car. In the area of town we stayed in, the Mitte, most buildings were six stories high, with shops and businesses on the ground floor and residential above. The public transportation in Berlin is extensive. There is the U-Bahn (underground), the S-Bahn (mostly elevated but some underground) and trams and buses. There are not THE BICYCLES of Amsterdam, but there are still twice as many bicycles in Berlin as cars. And not only do people in Berlin not own cars, they don’t drive them much when they do have them. In the US two thirds of trips under a mile are made by car compared to one third of such trips in Germany. In the Mitte, 13% of trips are made by bicycle, 30% by walking, 29% by public transit, and only 22% by private vehicle. This makes the private vehicle use roughly half that of San Francisco. The even more surprising part is that congestion is not linear: halving the number of cars reduces congestion to the point that the Mitte “feels” like it has only a fourth of San Francisco’s traffic. In addition, three fourths of Berlin’s streets have a 30 km per hour (18mph) speed limit. This may sound horribly limiting, but when you combine this speed with car-lite streets, car drivers actually get places faster than in American cities because there is so little congestion.

Biking in BerlinOne source of tranquility for this dense city of 3.5 million was surprising: in the capital of one of the world’s greatest car manufacturers, there just weren’t a whole lot of cars on the streets. In fact, the rate of car ownership in Berlin is lower than every other major city in Europe. (Even lower than Amsterdam.) Half of all Berlin households do not own a car. In the area of town we stayed in, the Mitte, most buildings were six stories high, with shops and businesses on the ground floor and residential above. The public transportation in Berlin is extensive. There is the U-Bahn (underground), the S-Bahn (mostly elevated but some underground) and trams and buses. There are not THE BICYCLES of Amsterdam, but there are still twice as many bicycles in Berlin as cars. And not only do people in Berlin not own cars, they don’t drive them much when they do have them. In the US two thirds of trips under a mile are made by car compared to one third of such trips in Germany. In the Mitte, 13% of trips are made by bicycle, 30% by walking, 29% by public transit, and only 22% by private vehicle. This makes the private vehicle use roughly half that of San Francisco. The even more surprising part is that congestion is not linear: halving the number of cars reduces congestion to the point that the Mitte “feels” like it has only a fourth of San Francisco’s traffic. In addition, three fourths of Berlin’s streets have a 30 km per hour (18mph) speed limit. This may sound horribly limiting, but when you combine this speed with car-lite streets, car drivers actually get places faster than in American cities because there is so little congestion. Tranquil Mitte neighborhoodThe car-lite streets combined with the low speed limits makes the Mitte area, even though densely populated, very livable. Low noise, low pollution, few vibrations. Pleasant for outdoor cafes; safe and easy to cross the street. Safe and easy to bicycle. On the whole the bicycle infrastructure I saw in Berlin ranged from pretty good to inadequate, much better than San Francisco but generally nowhere near as good as Amsterdam. However, because so many streets are so calm with just sporadic, slow-moving cars, bicycles sharing the road with cars on these streets isn’t so bad. The injury and death rates for pedestrians and bicyclists in Germany are a fraction of ours in the US. On the street we were staying, one with shops and many lively restaurants, probably only one car passed by a minute. Three times that number of bicycles and six times that number of pedestrians passed by in the same time frame. Just as a note, people tend to have nicer bikes in the Mitte than in Amsterdam. Part of this might be due to people storing their bicycles at night in the interior courtyards of their apartment buildings rather than out on the street.

Tranquil Mitte neighborhoodThe car-lite streets combined with the low speed limits makes the Mitte area, even though densely populated, very livable. Low noise, low pollution, few vibrations. Pleasant for outdoor cafes; safe and easy to cross the street. Safe and easy to bicycle. On the whole the bicycle infrastructure I saw in Berlin ranged from pretty good to inadequate, much better than San Francisco but generally nowhere near as good as Amsterdam. However, because so many streets are so calm with just sporadic, slow-moving cars, bicycles sharing the road with cars on these streets isn’t so bad. The injury and death rates for pedestrians and bicyclists in Germany are a fraction of ours in the US. On the street we were staying, one with shops and many lively restaurants, probably only one car passed by a minute. Three times that number of bicycles and six times that number of pedestrians passed by in the same time frame. Just as a note, people tend to have nicer bikes in the Mitte than in Amsterdam. Part of this might be due to people storing their bicycles at night in the interior courtyards of their apartment buildings rather than out on the street.Low car ownership levels might be due to Berlin’s high unemployment and relative poverty, at least in relation to the western parts of their country. It might be due to West Berlin and East Berlin spending several decades competing with each other as to who could provide better public transportation. It might be due to Berlin being flat and easy to bicycle around, although Berlin does get its fair share of rain and snow. It might be due to decent levels of fitness that makes walking fifteen minutes to get somewhere both practical and effortless for most people. It might be due to expensive parking; it might be due to people from the suburbs taking the excellent train network into the city rather than their cars. Infrastructure, habits, attitudes, years of investment, and car-lite government policies all add up.

Dozens of Chinese tourists wanted this shot (Marx and Engels)Right after settling into our apartment we went to the base of the crazy TV tower where we met up with our bicycle tour. Our guide was a British woman with a half-shaved head who absolutely adored Berlin and its history. She sure knew her stuff. As usual with a bicycle tour, we were able to cover days of sightseeing in four and a half hours, and this included wending our way through masses of drunken, singing football (soccer) fans, competing with hordes of Chinese tourists for photo opportunities, and a stop at a beer garden in the lovely woods of the Tiergarten. The tour covered many WWII and Cold War highlights. What was interesting was how the city itself appeared to celebrate the Cold War (and its eventual jubilant end) and played down WWII. One history is sung, the other mumbled. Perhaps, on reflection, this is not so surprising.

Dozens of Chinese tourists wanted this shot (Marx and Engels)Right after settling into our apartment we went to the base of the crazy TV tower where we met up with our bicycle tour. Our guide was a British woman with a half-shaved head who absolutely adored Berlin and its history. She sure knew her stuff. As usual with a bicycle tour, we were able to cover days of sightseeing in four and a half hours, and this included wending our way through masses of drunken, singing football (soccer) fans, competing with hordes of Chinese tourists for photo opportunities, and a stop at a beer garden in the lovely woods of the Tiergarten. The tour covered many WWII and Cold War highlights. What was interesting was how the city itself appeared to celebrate the Cold War (and its eventual jubilant end) and played down WWII. One history is sung, the other mumbled. Perhaps, on reflection, this is not so surprising. The happy historyAs the Russians and Germans fought through Berlin block by bitter block in April and early May of 1945, the city was pretty much bombed to rubble. When the war was over, anything left of the grand Nazi architecture was hurriedly obliterated. One of the few buildings intact from that grandiose era is the former Luftwaffe headquarters. Hitler’s New Reich Chancellery, built in one year by 4000 workers staffed round the clock, is no more, demolished by the Soviets, its blood-red marble carted away. On top of the bunker where Hitler spent his last days is merely a gravel parking lot. Not even a marker indicates what lurks beneath, but it’s all still down there, just bulldozed over. While Checkpoint Charlie has cheery actors in American and Soviet uniforms, and segments of the Berlin Wall are displayed around the city like public art, reminders of what preceded Berlin’s sad division are few. Maybe this is good; maybe neo-Nazis would just use Hitler’s bunker or palace as a shrine of adulation, but still it feels almost as if the Nazis have been photo-shopped out of the picture. Even the word “Hitler” has gained Voldemort-like unmentionable status. Given that Berlin is rife with twentieth-century history, we discussed the various eras and events with our kids, doing our best to make a distinction between the Nazis and the German people. However, in restaurants and on the U-Bahn, we soon learned to speak in undertones or in code when mentioning Hitler. Uncomfortable looks got sent our way otherwise.

The happy historyAs the Russians and Germans fought through Berlin block by bitter block in April and early May of 1945, the city was pretty much bombed to rubble. When the war was over, anything left of the grand Nazi architecture was hurriedly obliterated. One of the few buildings intact from that grandiose era is the former Luftwaffe headquarters. Hitler’s New Reich Chancellery, built in one year by 4000 workers staffed round the clock, is no more, demolished by the Soviets, its blood-red marble carted away. On top of the bunker where Hitler spent his last days is merely a gravel parking lot. Not even a marker indicates what lurks beneath, but it’s all still down there, just bulldozed over. While Checkpoint Charlie has cheery actors in American and Soviet uniforms, and segments of the Berlin Wall are displayed around the city like public art, reminders of what preceded Berlin’s sad division are few. Maybe this is good; maybe neo-Nazis would just use Hitler’s bunker or palace as a shrine of adulation, but still it feels almost as if the Nazis have been photo-shopped out of the picture. Even the word “Hitler” has gained Voldemort-like unmentionable status. Given that Berlin is rife with twentieth-century history, we discussed the various eras and events with our kids, doing our best to make a distinction between the Nazis and the German people. However, in restaurants and on the U-Bahn, we soon learned to speak in undertones or in code when mentioning Hitler. Uncomfortable looks got sent our way otherwise. Some wounds leave scarsBut the Cold War is visible in Berlin in spades, not only in relics and museums (the DDR museum manages to be both nostalgic and a hysterically sarcastic examination of Berlin’s cold war era) but in the physical scar still left by the Wall. The Wall itself wasn’t all that thick, but it included a no-man’s land that cut a swath through the city up to a hundred yards wide and 27 miles long. Berlin is still trying to figure out what to do with the space. Some want it eradicated as fast as possible to facilitate unity and healing; others see it as a creative void, allowing impromptu activities and events that are themselves monuments to freedom. Around the Brandenburg Gate the scar was easy to erase, just reinstate a great plaza that, while we were there, was filled with giant screens for the public to watch the Euro Cup competition, courtesy of Hyundai. (A Korean car company? Really?) Poor Brandenburg Gate, standing forlorn in the midst of barbed wire for so many years. I can imagine the exultation Berliners of both side must have felt to get it back. While many parts of the Wall’s scar have been filled, much remains, mutely reminding Berlin about its past and simultaneously raising questions about its future.

Some wounds leave scarsBut the Cold War is visible in Berlin in spades, not only in relics and museums (the DDR museum manages to be both nostalgic and a hysterically sarcastic examination of Berlin’s cold war era) but in the physical scar still left by the Wall. The Wall itself wasn’t all that thick, but it included a no-man’s land that cut a swath through the city up to a hundred yards wide and 27 miles long. Berlin is still trying to figure out what to do with the space. Some want it eradicated as fast as possible to facilitate unity and healing; others see it as a creative void, allowing impromptu activities and events that are themselves monuments to freedom. Around the Brandenburg Gate the scar was easy to erase, just reinstate a great plaza that, while we were there, was filled with giant screens for the public to watch the Euro Cup competition, courtesy of Hyundai. (A Korean car company? Really?) Poor Brandenburg Gate, standing forlorn in the midst of barbed wire for so many years. I can imagine the exultation Berliners of both side must have felt to get it back. While many parts of the Wall’s scar have been filled, much remains, mutely reminding Berlin about its past and simultaneously raising questions about its future.  A serious gateA simply amazing place in Berlin is the Pergamon Museum. For some reason, before I began researching our trip, I had never heard of it. I don’t know how this is possible. It’s like not knowing about the British Museum. Back at the turn of the century, when every wealthy colonial power wanted to show off its cultural prowess by carting off the remains of some ancient civilization, the Germans went gung ho in what is now Turkey and Iraq. They dug up some absolutely amazing stuff and brought it all back to Berlin, apparently without a twinge of conscience because everyone knew only northern Europeans could appreciate ancient cultures. So the Pergamon Museum now houses Babylon’s (yes, thatBabylon) absolutely enormous Gate of Ishtar, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world until the Lighthouse in Alexandria booted it off the list in the 6th century AD. Evidently what’s in the museum is just the small, frontal part of the gate. The big kahuna back part was deemed too large and is in storage. (Heck, just the front is nearly five stories high.) The Pergamon Museum is also home to (and named after) the great Pergamon Altar, a prized example of Hellenic art and architecture. It was reconstructed in its entirety so that today we can walk up and down its steps and pretend we live two millennia ago in the Pergamene Kingdom. And there is the Market Gate of Miletus, perhaps my favorite exhibit at the Pergamon. The history of Miletus (located, like Pergamon, in what is now Turkey) begins in the mists of the Bronze Age. After several incarnations it eventually wound up as an Ionian Greek city and produced philosophers, writers, architects, even urban planners. Miletus must’ve prospered because the Market Gate dates from the second century AD and reflects Roman rather than Hellenistic design. The gate was shaken down by an earthquake around 1100 AD and then waited eight centuries for the Germans to put it back together like Humpty Dumpty. If I could be a time tourist, I would visit its crumbling, magnificent ruins just before that quake.

A serious gateA simply amazing place in Berlin is the Pergamon Museum. For some reason, before I began researching our trip, I had never heard of it. I don’t know how this is possible. It’s like not knowing about the British Museum. Back at the turn of the century, when every wealthy colonial power wanted to show off its cultural prowess by carting off the remains of some ancient civilization, the Germans went gung ho in what is now Turkey and Iraq. They dug up some absolutely amazing stuff and brought it all back to Berlin, apparently without a twinge of conscience because everyone knew only northern Europeans could appreciate ancient cultures. So the Pergamon Museum now houses Babylon’s (yes, thatBabylon) absolutely enormous Gate of Ishtar, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world until the Lighthouse in Alexandria booted it off the list in the 6th century AD. Evidently what’s in the museum is just the small, frontal part of the gate. The big kahuna back part was deemed too large and is in storage. (Heck, just the front is nearly five stories high.) The Pergamon Museum is also home to (and named after) the great Pergamon Altar, a prized example of Hellenic art and architecture. It was reconstructed in its entirety so that today we can walk up and down its steps and pretend we live two millennia ago in the Pergamene Kingdom. And there is the Market Gate of Miletus, perhaps my favorite exhibit at the Pergamon. The history of Miletus (located, like Pergamon, in what is now Turkey) begins in the mists of the Bronze Age. After several incarnations it eventually wound up as an Ionian Greek city and produced philosophers, writers, architects, even urban planners. Miletus must’ve prospered because the Market Gate dates from the second century AD and reflects Roman rather than Hellenistic design. The gate was shaken down by an earthquake around 1100 AD and then waited eight centuries for the Germans to put it back together like Humpty Dumpty. If I could be a time tourist, I would visit its crumbling, magnificent ruins just before that quake. Miletus, put back together

Miletus, put back together Imagine our surpriseBut ancient treasures are not the only surprises in Berlin. A block from our apartment, we saw a restaurant sign that curiously said, “Dolores.” Well, that didn’t sound German. Peeking our heads in, we saw a map of our San Francisco neighborhood spread out larger than life on the wall! It turns out Dolores is a well-reviewed gourmet burrito place that pays tribute to San Francisco. Of course we ate lunch there, and while the burritos aren’t exactly the same as the ones in the Mission, they were quite tasty. I suppose if they’d named themselves “Valencia,” that would’ve been even more hipster cool, but next time you’re in Berln, I say check them out.

Imagine our surpriseBut ancient treasures are not the only surprises in Berlin. A block from our apartment, we saw a restaurant sign that curiously said, “Dolores.” Well, that didn’t sound German. Peeking our heads in, we saw a map of our San Francisco neighborhood spread out larger than life on the wall! It turns out Dolores is a well-reviewed gourmet burrito place that pays tribute to San Francisco. Of course we ate lunch there, and while the burritos aren’t exactly the same as the ones in the Mission, they were quite tasty. I suppose if they’d named themselves “Valencia,” that would’ve been even more hipster cool, but next time you’re in Berln, I say check them out.  Furnish your apartment

Furnish your apartment

Flea Market finds

Flea Market findsWhen you’ve had your burrito and really want to fill your hipster quota, the flea market next to the Mauerpark, (literally “Wall Park,” because it was created from a stretch of Wall scar) is the place to go. You can even take the U-Bahn to get there! By our third day in Berlin, after all the museums and culture Mom tried to cram down her throat, youngest daughter was longing for Shopping. Now Mom is not much of a Shopper and isn’t particularly inclined to spend vacation time on the activity. But many museums had indisputably been entered, and a compromise was in order. The Mauerpark flea market turned out to be not only a Shopping Delight to younger daughter, it was also enough of a Cultural Excursion to placate Mom. (Other family members shopped or appreciated cultural niceties in varying degrees.) In addition, it was very Good Value, pleasing to mother and daughter alike. At the Mauerpark market you could outfit an entire apartment, down to the kitchen appliances. You could dress yourself and three thousand of your closest friends, outfit half the bands at Woodstock with instruments, eat a dozen different ethnic foods, buy communist memorabilia (real and fake), obtain a flotilla of marginally working typewriters--it was all there in the run-down but friendly and comfortable splendor of Mauerpark market’s vast acres. As you leave you might even be greeted by a local, scrap-iron robot like we were.

Path among stelaeAnother way Berlin has filled its Wall scar is with the extraordinary new Holocaust Memorial, inaugurated in 2005. Designed by American architect Peter Eisenman, it goes even further than the Vietnam Memorial in Washington as an interactive way not only to honor the dead, not only to feel and grieve the loss, but, in this case, to actually comprehend some of the alienation, fear and disorientation that was endemic to this dreadful period of time. First off, the memorial is huge, covering more than four acres. It is made up of stelae (large rectangular stones) placed on end in a grid pattern. But the ground is not flat; it slopes and rolls in waves. The stelae are not straight either, but rather cant like headstones in an old cemetery. Walking through the tall sections, you can only see straight ahead or straight to the side. The sky above feels a long ways away. Though you know can always walk out, you have no idea where your family members have gotten to. The hundreds of people traversing the paths with you appear and disappear between these massive stones in the blink of an eye. You feel oddly alone. Distances seem long, never-ending. And you begin to wonder what it would feel like to be split from your family, loaded in a rail car, nothing familiar, nothing secure, to a fate unknown. These acres of grey stelae form a maze of Kafkaesque surrealism, a cemetery of broken dreams. To wander here is to be Alice fallen down the rabbit hole into a terminally grey, merciless world. I recommend it.

Path among stelaeAnother way Berlin has filled its Wall scar is with the extraordinary new Holocaust Memorial, inaugurated in 2005. Designed by American architect Peter Eisenman, it goes even further than the Vietnam Memorial in Washington as an interactive way not only to honor the dead, not only to feel and grieve the loss, but, in this case, to actually comprehend some of the alienation, fear and disorientation that was endemic to this dreadful period of time. First off, the memorial is huge, covering more than four acres. It is made up of stelae (large rectangular stones) placed on end in a grid pattern. But the ground is not flat; it slopes and rolls in waves. The stelae are not straight either, but rather cant like headstones in an old cemetery. Walking through the tall sections, you can only see straight ahead or straight to the side. The sky above feels a long ways away. Though you know can always walk out, you have no idea where your family members have gotten to. The hundreds of people traversing the paths with you appear and disappear between these massive stones in the blink of an eye. You feel oddly alone. Distances seem long, never-ending. And you begin to wonder what it would feel like to be split from your family, loaded in a rail car, nothing familiar, nothing secure, to a fate unknown. These acres of grey stelae form a maze of Kafkaesque surrealism, a cemetery of broken dreams. To wander here is to be Alice fallen down the rabbit hole into a terminally grey, merciless world. I recommend it. What I don’t recommend is this: while grabbing a bite to eat near the Brandenburg Gate at food stands set up for the Euro Cup viewing, do not, I repeat, do not order the currywurst. Unless, indeed, an indifferent hot dog glopped with some tasteless brown sauce and sprinkled with some sorry curry power shaken directly from a cardboard box sounds like your idea of an appetizing meal. I didn’t like it much as I ate it, and I liked it even less the next few hours that followed. In fact, I can’t understand how anyone would like it, especially given the excellent traditional German food we had at the beer garden the previous evening. In general I liked the food in Berlin. In general I made smart choices on the cuisine front—after all, I was smart enough to avoid the sushi sold on the U-Bahn subway platforms. (Someone is going to buy sushi there? Really?) But let me tell you, in the future I will avoid currywurst like the plague. As we were leaving Berlin and I was trying to decipher which platform our train was leaving from (a task not entirely stress-free given my scant ability to read German) my son said it was too bad we didn’t have time to visit the Currywurst Museum this trip. I gave him a dirty look, my family at that point being well acquainted with my currywurst debacle. My son said, “No, really! Didn’t you see the ad for it back there?” I thought he was seriously trying to annoy me, but I went over to where he pointed. No doubt he was indeed trying to annoy me, but he was also telling the truth. There was a sign with a freaking chopped-up hotdog with a face that said CURRYWURST MUSEUM. Here is a video about the place. Click on it and watch it. I’m not kidding. Watch it to the end. It is 2 minutes and 30 seconds of insane evil German satire. The people who made it are rolling on the floor laughing even now. It is the only explanation I have because no one in their right mind would CREATE A WHOLE MUSEUM ABOUT CURRYWURST. Honestly, I’m going to have to go back to Berlin just to see if this museum actually exists. If it does, I may weep.

What I don’t recommend is this: while grabbing a bite to eat near the Brandenburg Gate at food stands set up for the Euro Cup viewing, do not, I repeat, do not order the currywurst. Unless, indeed, an indifferent hot dog glopped with some tasteless brown sauce and sprinkled with some sorry curry power shaken directly from a cardboard box sounds like your idea of an appetizing meal. I didn’t like it much as I ate it, and I liked it even less the next few hours that followed. In fact, I can’t understand how anyone would like it, especially given the excellent traditional German food we had at the beer garden the previous evening. In general I liked the food in Berlin. In general I made smart choices on the cuisine front—after all, I was smart enough to avoid the sushi sold on the U-Bahn subway platforms. (Someone is going to buy sushi there? Really?) But let me tell you, in the future I will avoid currywurst like the plague. As we were leaving Berlin and I was trying to decipher which platform our train was leaving from (a task not entirely stress-free given my scant ability to read German) my son said it was too bad we didn’t have time to visit the Currywurst Museum this trip. I gave him a dirty look, my family at that point being well acquainted with my currywurst debacle. My son said, “No, really! Didn’t you see the ad for it back there?” I thought he was seriously trying to annoy me, but I went over to where he pointed. No doubt he was indeed trying to annoy me, but he was also telling the truth. There was a sign with a freaking chopped-up hotdog with a face that said CURRYWURST MUSEUM. Here is a video about the place. Click on it and watch it. I’m not kidding. Watch it to the end. It is 2 minutes and 30 seconds of insane evil German satire. The people who made it are rolling on the floor laughing even now. It is the only explanation I have because no one in their right mind would CREATE A WHOLE MUSEUM ABOUT CURRYWURST. Honestly, I’m going to have to go back to Berlin just to see if this museum actually exists. If it does, I may weep. Ein BerlinerNote: “Ich bich ein Berliner” means both “I am one with the people of Berlin” and “I am a jelly doughnut.” However, it’s an urban legend that Kennedy gaffed with the latter because his audience would have known he was saying the former. Or so I’m told.

Ein BerlinerNote: “Ich bich ein Berliner” means both “I am one with the people of Berlin” and “I am a jelly doughnut.” However, it’s an urban legend that Kennedy gaffed with the latter because his audience would have known he was saying the former. Or so I’m told. Next stop: "Sparkling, Technicolor Prague"

Published on August 28, 2012 23:05

August 13, 2012

A Tale of Five Cities--Charming, Livable Amsterdam

Earlier this summer my family visited five European cities: Amsterdam, Berlin, Prague, Vienna and Venice. We chose in advance not to rent a car and instead used the myriad other transportation options available in Europe. We walked and biked. We rode street-level trams, elevated light rail, underground metros, and electric passenger trains between cities. We were transported by horse-drawn carriage, water buses and a gondola. In Berlin we even rode an octo-bike (actually only a septo-bike, but the experience was not unlike riding an octopus.)

Each of these cities was amazing and delightful in its own way, but there were remarkable differences beyond the cuisine and languages spoken. In Amsterdam, seventy year olds smoked past us on their bicycles; in Venice I learned you cannot get any kind of coffee to go to save your life. In Berlin, I saw my San Francisco neighborhood plastered on a restaurant wall; in Vienna I was surprised to discover perhaps the most innovatively green city in Europe. On the downside, I learned to never ever order currywurst or rent a bike with coaster brakes again. (Some things you have to just chalk up to experience.) Come and savor my trip with me, with a special emphasis on transportation and city livability. Of course four days in a city does not an expert make, but things I observed that surprised me may surprise you, too.

In this post, I’ll tackle the first city we visited—Amsterdam.

Of course being an avid fan of bicycles—and Amsterdam being a Mecca for all things bicycle--I was looking forward tremendously to my first trip ever here. But even with the reading I’d done, I was unprepared for what I found. First off, Amsterdam is much older and more charming than I expected. I don’t know why, but I imagined it to be harsh and modern. No, no, no! Amsterdam of canals and cafes and bridges and small streets is anything but that. And for an entry point to Europe, it is superb for dipping one’s linguistic toes. Though signs and names of places are in Dutch, pretty much everyone speaks excellent English. Easy-peasy for asking questions and getting around. Communication would grow more challenging as our trip progressed.

Intersection near our apartmentNext off, though of course I knew of the bicycles, I didn’t really understand THE BICYCLES in Amsterdam. The word “ubiquitous” might have been invented just for them. They are everywhere, either in motion or parked on the street. What I also didn’t expect is that for the newbie, riding a bicycle in Amsterdam alternates between unsettling and terrifying, at least for the first couple days. It got better by the third day, and I realize it was due to not being used to how the Dutch do things, but still, even with all our years of experience riding in San Francisco, and even with all the good Dutch separated bicycle infrastructure, Amsterdam was not for the uninitiated faint of heart. I suppose it is akin to taking someone who has only ever driven on the back roads of Wyoming and plopping them behind the wheel in downtown San Francisco. Eventually the person would learn to cope, but the first few days would be hairy.

Intersection near our apartmentNext off, though of course I knew of the bicycles, I didn’t really understand THE BICYCLES in Amsterdam. The word “ubiquitous” might have been invented just for them. They are everywhere, either in motion or parked on the street. What I also didn’t expect is that for the newbie, riding a bicycle in Amsterdam alternates between unsettling and terrifying, at least for the first couple days. It got better by the third day, and I realize it was due to not being used to how the Dutch do things, but still, even with all our years of experience riding in San Francisco, and even with all the good Dutch separated bicycle infrastructure, Amsterdam was not for the uninitiated faint of heart. I suppose it is akin to taking someone who has only ever driven on the back roads of Wyoming and plopping them behind the wheel in downtown San Francisco. Eventually the person would learn to cope, but the first few days would be hairy.I am a big believer in bicycle tours as a way to get acquainted with a city. On a bicycle with a guide you can cover in half a day what takes two days to see on foot. Since my husband and son were arriving a day after us, my daughters and I took a four-hour city tour of Amsterdam that covered the usual tourist high points with some history, humor and city mythology thrown in for good measure. The biking was a little dicey here and there, but our guide took care of us and got our group of thirteen around town in one piece without too much trauma. At the end of the tour, my girls and I gulped and bravely decided to rent bikes to take on our own for a few days. Then things got interesting.

First off our bikes, while relatively shiny and new, weren’t great. They had coaster brakes. (Never again.) The steering was far from nimble and it was hard to go much faster than a mild glide. I longed for my bike back in San Francisco. And since we were completely new to Amsterdam, we were the proverbial clueless tourists, constantly consulting a map. (Indeed, over half of the pictures taken of me during this entire trip in Europe show moi, family navigator, map in hand.) Still, the next day we were able to bike to the museums and all around town to show my son and husband what we’d seen on our tour the day before.

Separated from carsThough the bike lanes were almost always wide enough to ride two abreast, we mostly rode in single file to allow the locals to fly past us, even the sixty and seventy year olds. (These people are good at biking! It pays to start young and do it your whole life.) As far as I could tell, there are no stop signs in Amsterdam. I didn’t see one. There are intersections controlled by stoplights, which sometimes have a separate light for bikes and sometimes don’t, and sometimes have two parts and sometimes don’t. (Were we sometimes confused? Yes.) There are completely uncontrolled intersections (especially in the inner ring area.) And there is yielding when minor roads meet major ones. Because there are few cars in the inner ring area with its narrow streets and lovely 17th century buildings, the uncontrolled intersections here primarily involve bikes, although cars traveling slowly are definitely in the mix. But the bikes are incredible. Everyone just goes, and somehow no one hits each other. At first we would stop and try to find a gap in passing traffic. What noobs. Then we just started biking with faith no one would hit us. And no one did. It all just mysteriously works. (It helps that while Amsterdamers don’t poke along by any means, they usually ride under 15 mph and are extremely adept at judging other bicycles’ speeds and swerving accordingly.) The one thing that didn’t work for me were the motorbikes and Vespas allowed to use the bike lanes. Noisy, smelly nasty things that could just as well drive with the cars since the cars didn’t go any faster than they did.

Separated from carsThough the bike lanes were almost always wide enough to ride two abreast, we mostly rode in single file to allow the locals to fly past us, even the sixty and seventy year olds. (These people are good at biking! It pays to start young and do it your whole life.) As far as I could tell, there are no stop signs in Amsterdam. I didn’t see one. There are intersections controlled by stoplights, which sometimes have a separate light for bikes and sometimes don’t, and sometimes have two parts and sometimes don’t. (Were we sometimes confused? Yes.) There are completely uncontrolled intersections (especially in the inner ring area.) And there is yielding when minor roads meet major ones. Because there are few cars in the inner ring area with its narrow streets and lovely 17th century buildings, the uncontrolled intersections here primarily involve bikes, although cars traveling slowly are definitely in the mix. But the bikes are incredible. Everyone just goes, and somehow no one hits each other. At first we would stop and try to find a gap in passing traffic. What noobs. Then we just started biking with faith no one would hit us. And no one did. It all just mysteriously works. (It helps that while Amsterdamers don’t poke along by any means, they usually ride under 15 mph and are extremely adept at judging other bicycles’ speeds and swerving accordingly.) The one thing that didn’t work for me were the motorbikes and Vespas allowed to use the bike lanes. Noisy, smelly nasty things that could just as well drive with the cars since the cars didn’t go any faster than they did. A gazillion bikes at the central train stationOutside of the inner ring area, when riding the mix of minor and major roads, I observed that the minor roads have very few cars, rendering them for the most part quite tranquil. Transitioning from a minor onto a major road in a car required some care. Cars often had to cross a distinct raised area separate in style and color from the road and first yield to pedestrians, then to bikes, and then could make a turn (or, heaven forbid, go straight across) when a gap in car traffic appeared. The cars were very good about yielding in these situations. I didn’t see even one try to push its nose through a mess of pedestrians or bikes. In fact, if you were a bike on a major road approaching a car on a minor one, you could be confident they would see you and wait for you to pass. The only times I felt threatened by cars in Amsterdam were on the narrow inner ring roads adjacent to the canals where there was not room to pass however much we tried to hug the right-hand side. (Door zone!) Though there were few cars on these roads, the ones that were there would hang behind impatiently and squeeze past the second they had the chance. One car came so close its mirror actually knocked my handlebar. (I was indignant. This was Amsterdam—land of pure biking!)

A gazillion bikes at the central train stationOutside of the inner ring area, when riding the mix of minor and major roads, I observed that the minor roads have very few cars, rendering them for the most part quite tranquil. Transitioning from a minor onto a major road in a car required some care. Cars often had to cross a distinct raised area separate in style and color from the road and first yield to pedestrians, then to bikes, and then could make a turn (or, heaven forbid, go straight across) when a gap in car traffic appeared. The cars were very good about yielding in these situations. I didn’t see even one try to push its nose through a mess of pedestrians or bikes. In fact, if you were a bike on a major road approaching a car on a minor one, you could be confident they would see you and wait for you to pass. The only times I felt threatened by cars in Amsterdam were on the narrow inner ring roads adjacent to the canals where there was not room to pass however much we tried to hug the right-hand side. (Door zone!) Though there were few cars on these roads, the ones that were there would hang behind impatiently and squeeze past the second they had the chance. One car came so close its mirror actually knocked my handlebar. (I was indignant. This was Amsterdam—land of pure biking!)

Car-lite inner ring areaThe reduced number of cars (and reduced attendant noise and stress and smells) is definitely part of what makes Amsterdam so charming and livable. I would guess there are half as many moving vehicles per square mile in Amsterdam as there are per square mile in San Francisco. All three of my kids ranked Amsterdam either 1 or 2 of the cities we visited in terms of places they could imagine living, perhaps in part because Amsterdam resembles San Francisco in both size and live-and-let-live attitude. The districts of Amsterdam I saw were more dense than San Francisco but not by much. Most buildings were four or five stories tall, retail was located under residential, there were few chain stores (though, yes, there were Starbucks), lots of shops and cafes. The apartment we rented was quite large—four bedrooms on the second floor, living room, dining room and kitchen on the first, garden in the back. (Our landlady’s unit above us occupied floors 3 and 4.) Tram one block away; grocery and other stores right around the corner. I could definitely see how you could raise a family here.

Car-lite inner ring areaThe reduced number of cars (and reduced attendant noise and stress and smells) is definitely part of what makes Amsterdam so charming and livable. I would guess there are half as many moving vehicles per square mile in Amsterdam as there are per square mile in San Francisco. All three of my kids ranked Amsterdam either 1 or 2 of the cities we visited in terms of places they could imagine living, perhaps in part because Amsterdam resembles San Francisco in both size and live-and-let-live attitude. The districts of Amsterdam I saw were more dense than San Francisco but not by much. Most buildings were four or five stories tall, retail was located under residential, there were few chain stores (though, yes, there were Starbucks), lots of shops and cafes. The apartment we rented was quite large—four bedrooms on the second floor, living room, dining room and kitchen on the first, garden in the back. (Our landlady’s unit above us occupied floors 3 and 4.) Tram one block away; grocery and other stores right around the corner. I could definitely see how you could raise a family here. Contraflow bike lane on one-way streetAmsterdam was not high on the MAMIL index (Middle Aged Males in Lycra, a species of bicyclist my husband sometimes claims membership to.) Very little Lycra at all except for a few guys on long distance training runs. People simply rode bikes in whatever they were wearing for the day. No one wore helmets either, except a couple in Lycra. It’s a curious thing, but even though absolutely no one wears helmets, the Dutch have the lowest bicycling injury and mortality rate of any country in the West, indeed a mere fraction of our own rate. (Conclusion? Helmet use does not create bicyclist safety; good bicycle infrastructure and cars that yield create bicyclist safety.) Since there were no stop signs in Amsterdam, I never saw a bike run one, and I think I saw only one bicyclist run a red after stopping at a light. The lights, however, were very short, and we sometimes had difficulty getting all five of us across an intersection in one light cycle. Though many bike paths were asphalt, some were made of pavers laid so smoothly on sand it felt like you were riding on asphalt. Pretty great. So for those who predict peak oil means no more bike lanes, this is not necessarily the case.

Contraflow bike lane on one-way streetAmsterdam was not high on the MAMIL index (Middle Aged Males in Lycra, a species of bicyclist my husband sometimes claims membership to.) Very little Lycra at all except for a few guys on long distance training runs. People simply rode bikes in whatever they were wearing for the day. No one wore helmets either, except a couple in Lycra. It’s a curious thing, but even though absolutely no one wears helmets, the Dutch have the lowest bicycling injury and mortality rate of any country in the West, indeed a mere fraction of our own rate. (Conclusion? Helmet use does not create bicyclist safety; good bicycle infrastructure and cars that yield create bicyclist safety.) Since there were no stop signs in Amsterdam, I never saw a bike run one, and I think I saw only one bicyclist run a red after stopping at a light. The lights, however, were very short, and we sometimes had difficulty getting all five of us across an intersection in one light cycle. Though many bike paths were asphalt, some were made of pavers laid so smoothly on sand it felt like you were riding on asphalt. Pretty great. So for those who predict peak oil means no more bike lanes, this is not necessarily the case. Canal bridge with forbidden bike parkingGiven the bicycle vs. auto mode share in Amsterdam (38% vs 25%) a dispro- portionate amount of space is devoted to cars and their storage. Though there is separated bicycle infrastructure on all major roads, the lanes are overly crowded because so many bicyclists are using them at all times! Because there are precious few bike racks for people to lock their bikes to, bikes are littered everywhere, even locked to canal bridge railings (supposedly a big no-no.) Since the Dutch seem fond of practicality and order, I’m mystified why they don’t take a couple car parking spots per block and create tidy bike corral parking for 30. I also don’t understand the Dutch penchant for incredibly heavy, cloth-covered chains rather than the much lighter, less awkward U-locks we use here. Our landlady in the apartment we rented (in the Oud Zuid district) was so worried about our rental bikes being stolen (even with all five locked together) that she insisted we lock our bikes to her family’s bikes that were chained to the building. The next day she coasted off on her own bike to a rehearsal at the Concertgebouw where she is a violinist. Bicyclists silently glided by our apartment (not in a touristy part of town at all) from six in the morning until well after midnight. Small children came with their parents, preteens rode alone, business people in formal wear cycled past, elderly grey-haired women with their shopping in their baskets whizzed by. Ordinary, real Amsterdamers really do bike just for basic transportation because they’ve designed their city to make bicycling fast, safe, pleasant and convenient.

Canal bridge with forbidden bike parkingGiven the bicycle vs. auto mode share in Amsterdam (38% vs 25%) a dispro- portionate amount of space is devoted to cars and their storage. Though there is separated bicycle infrastructure on all major roads, the lanes are overly crowded because so many bicyclists are using them at all times! Because there are precious few bike racks for people to lock their bikes to, bikes are littered everywhere, even locked to canal bridge railings (supposedly a big no-no.) Since the Dutch seem fond of practicality and order, I’m mystified why they don’t take a couple car parking spots per block and create tidy bike corral parking for 30. I also don’t understand the Dutch penchant for incredibly heavy, cloth-covered chains rather than the much lighter, less awkward U-locks we use here. Our landlady in the apartment we rented (in the Oud Zuid district) was so worried about our rental bikes being stolen (even with all five locked together) that she insisted we lock our bikes to her family’s bikes that were chained to the building. The next day she coasted off on her own bike to a rehearsal at the Concertgebouw where she is a violinist. Bicyclists silently glided by our apartment (not in a touristy part of town at all) from six in the morning until well after midnight. Small children came with their parents, preteens rode alone, business people in formal wear cycled past, elderly grey-haired women with their shopping in their baskets whizzed by. Ordinary, real Amsterdamers really do bike just for basic transportation because they’ve designed their city to make bicycling fast, safe, pleasant and convenient.  Typical Dutch bikesGarages were few and far between and pretty much no one appeared to bring their bikes inside where they live. (Perhaps they are unwilling to track dirt and muck in when it rains?) So, since Dutch bikes live outside all year around, vulnerable to both weather and thieves, the average Dutch bike looked heavy, rusted, and as if it first touched pavement in 1938. Yes, Amsterdam is flat (if you don’t count the Dutch “hills”, a.k.a. canal bridges) but they handicap themselves by riding incredibly heavy (though stately, dignified and indestructible) bikes. Though in San Francisco we have hills, we also tend to have lighter, more nimble bikes with decent gears to deal with inclines. And if you have a nice bike, you sure as heck don’t leave it out on the street at night.

Typical Dutch bikesGarages were few and far between and pretty much no one appeared to bring their bikes inside where they live. (Perhaps they are unwilling to track dirt and muck in when it rains?) So, since Dutch bikes live outside all year around, vulnerable to both weather and thieves, the average Dutch bike looked heavy, rusted, and as if it first touched pavement in 1938. Yes, Amsterdam is flat (if you don’t count the Dutch “hills”, a.k.a. canal bridges) but they handicap themselves by riding incredibly heavy (though stately, dignified and indestructible) bikes. Though in San Francisco we have hills, we also tend to have lighter, more nimble bikes with decent gears to deal with inclines. And if you have a nice bike, you sure as heck don’t leave it out on the street at night.By day three we had almost gotten biking in Amsterdam figured out, although my youngest was still nervous about crossing intersections after an incident with a tram. (Trams apparently have the right of way over everybody and do not take kindly to fourteen-year-old girls who are still in the middle of an intersection when the light turns red.) At this point we took a countryside tour to see what things looked like outside of the city. It was a different tour company with better bikes, which made me happy. We were impressed after twenty minutes of biking to be completely away from the city in open countryside. We took some great bikeways through parks, over a canal with locks, through a forest, through polders/reclaimed land, always either on pathways separate from cars or on roads with very few cars. We tasted cheese, saw an old windmill, visited a clog maker, the usual tourist stuff. We learned that when it comes to hydrological engineering, the Dutch are masters (a skill they will need in a big way with rising sea levels.) A very enjoyable afternoon.

Not much space for pedestrians (bike path in middle)So we come to the walking experience in this land of bicycles. Though we biked a lot, we also walked miles and miles in Amsterdam. It is a lovely place to wander around. There are some pedestrian esplanade/ plazas connecting residential areas that are idyllic, and the whole inner ring area is great fun for people watching/ window shopping/strolling. However, although sometimes Amsterdam’s bicycle lanes and bike parking seems to come from space previously given to cars, other times it appears carved from pedestrian ways, leaving pedestrians too little space. In addition, the first two days when walking in Amsterdam, even though I was warned, we nearly got run over by bicycles. By the third day we learned to always, always (!) look for bikes before crossing a bike path or just stepping anywhere at any time. Just as in San Francisco we would never step into the street without glancing for cars, so for the Dutch looking for bicycles is instinctive. As far as I could tell, bicyclists do not yield to pedestrians in Amsterdam. The Dutch see nothing wrong with this, probably because they are all bicyclists more than pedestrians themselves. In fact, when I stopped for pedestrians in cases where they seemed to clearly have the right of way (i.e. a crosswalk), the pedestrians looked at me with bemused confusion and waited for me to pass. After a time or two of this, I shrugged my shoulders, said “when in Rome,” and proceeded to ignore pedestrians thereafter.

Not much space for pedestrians (bike path in middle)So we come to the walking experience in this land of bicycles. Though we biked a lot, we also walked miles and miles in Amsterdam. It is a lovely place to wander around. There are some pedestrian esplanade/ plazas connecting residential areas that are idyllic, and the whole inner ring area is great fun for people watching/ window shopping/strolling. However, although sometimes Amsterdam’s bicycle lanes and bike parking seems to come from space previously given to cars, other times it appears carved from pedestrian ways, leaving pedestrians too little space. In addition, the first two days when walking in Amsterdam, even though I was warned, we nearly got run over by bicycles. By the third day we learned to always, always (!) look for bikes before crossing a bike path or just stepping anywhere at any time. Just as in San Francisco we would never step into the street without glancing for cars, so for the Dutch looking for bicycles is instinctive. As far as I could tell, bicyclists do not yield to pedestrians in Amsterdam. The Dutch see nothing wrong with this, probably because they are all bicyclists more than pedestrians themselves. In fact, when I stopped for pedestrians in cases where they seemed to clearly have the right of way (i.e. a crosswalk), the pedestrians looked at me with bemused confusion and waited for me to pass. After a time or two of this, I shrugged my shoulders, said “when in Rome,” and proceeded to ignore pedestrians thereafter.We opted to mostly walk and bike rather than take public transport in Amsterdam, though when we did take the tram I was amazed at how insanely quiet it was, both inside and out (especially when compared to San Francisco’s noisy behemoths.) Truly, it made me wonder what the heck is wrong with us that our light rail is so clunky and loud. The trams were a bit on the pricey side--a one-hour ticket was 2.7 Euros (about $3.30)—but residents can buy a monthly ticket for 81 euros, which is more in line with SF Muni prices. However, the trams were not ever packed as far as I could tell. There is also an underground metro in Amsterdam but it didn’t seem to serve the city center much and we didn’t use it. The bicycle really seemed to be the way to get around. If I were to do our trip all over again, I would rent better bikes and spring real money to get a decent map, but I would definitely bike again in Amsterdam despite the hair-raising nature of the first days.

Just as a note, two themes we heard a lot about in Amsterdam were 1) total national distress that the Dutch football (i.e. soccer) team had gotten tossed out early in the Euro Cup rounds, and 2) that everyone was thrilled to see the sun that week since they hadn’t seen it in a while. (They basically implied that it rained there constantly, worse than Seattle. Indeed, their annual precipitation levels are comparable.) In addition, World War II still casts its shadow here, and not only at the Anne Frank House. Right outside our apartment was a haunting statue of three men, representing the twenty-nine neighborhood men executed by Nazi occupiers right at that spot in retaliation after a Nazi officer stationed across the street was killed by resistance fighters.

I was impressed at how athletic the Dutch are. There is a range of body types, some slim, some heavier, but everyone was fit, no one obese, everyone more than up to a sprightly walk or bike ride. In fact, the Dutch think there’s no better way to spend a weekend than getting some exercise and fresh air out in the country. And they long for cold snaps to freeze over the canals (which doesn’t happen often) because then they get to skate! This attitude towards fitness and incorporating exercise into their everyday lives may be why the Dutch spend 60% as much on health care as the US does (counting both public + private expenditures), have an adult obesity rate of only 12% (compared to ours of 34%), and also have a longer life expectancy to boot. (It can’t be their alcohol or cigarette consumption—they smoke and drink more than we do. However they do drink less than half the soda pop that we consume.)

As we took an early train out of Amsterdam the last morning, we passed through suburbs and then villages and small towns spaced farther apart. On every road I could see there were substantially more bikes than cars zipping happily along in the morning sunshine.

Next stop: Evolving, Fascinating Berlin.

Note: While it’s far preferable to reduce one’s carbon emissions rather than purchase offsets for them, for this trip we did buy carbon offsets for our airplane flights through Terrapass, a company that does a good job of funding carbon/methane reduction projects that would not happen otherwise.

Published on August 13, 2012 13:37

July 17, 2012

The Different Kinds of Hope

There is more than one kind of hope.

There is more than one kind of hope.First off, there is the no-hope kind of hope, believing nothing can change a situation. The plug has been pulled, and all that's left is to watch the water swirl down the drain. And indeed there are times when events are so large and already in play that there's little one can do. If a tsunami threatens, you run as far and as high as you can, but you aren’t going to move your house or stop the water. It’s too late for that. On a drier day, if your house catches fire, you can try to put it out, but at a certain point it’s best just to get out and watch it burn. Stay alive to rebuild another day. If you have a terminal illness you can undergo various costly procedures that have little chance of working, or, with as much equanimity as you can muster, you can focus on the quality of life of the time you have left. So there are situations when no hope (the acceptance phase in Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief) is the right choice. Some might call it pessimism, some might call it realism. It can be seen as giving in to despair or just sheer logic and pragmatism. Sometimes, though, "no hope" is used as an excuse when something actually could've been done to remedy a situation. Sometimes "there's no hope" is short-hand for "I just don't want to inconvenience myself in any way."

Then there is passive hope. The belief that, in spite of everything, things will work out for the best. That somehow, without effort on our part, our problems will be solved. And indeed, sometimes the universe does seem to work in mysterious ways. One of my favorite themes running through Shakespeare in Love:

Hugh Fennyman

: So what do we do?

Hugh Fennyman

: So what do we do? Philip Henslowe : Nothing. Strangely enough, it all turns out well.

Hugh Fennyman : How?

Philip Henslowe : I don't know. It's a mystery.

A caricature of passivity, Henslowe goes with the flow even though it makes him anxious and he nearly gets his ear cut off. And, lo and behold, his philosophy proves sound! Things work out with very little intervention on his part. Happy endings abound, or at least the show goes on.

The last kind of hope is active hope. It requires action in the face of uncertainty. We hope that our children will grow up happy and healthy. We can’t guarantee it, but we take as much action towards that goal as we can, and then optimistically hope for the best.

The universe appears to like those crazy optimists. Studies show that while pessimists have a much more accurate view of circumstances, optimists have better outcomes in life. This is because by believing a situation is rosier then it actually is, optimists try. They don’t give up, they don’t admit defeat before they’ve even begun. So because they try, they succeed more often than pessimists whose more realistic understanding of a situation leads them not to try at all.

But these studies only hold true for active optimists, not passive ones.

Consider this scenario: you have a patch of ground in your yard and you would like it to produce fresh vegetables for you. A pessimist might say that there isn't enough sun, the soil is too compacted, the probability of pests too great to make a garden worth the effort. An active optimist would loosen the soil, add the compost and fertilizer, trim back some overhead branches to let in more light, plant the seeds, and see what happens. Maybe the pessimist is right, maybe the garden will not produce, but the active optimist is willing to put in the effort and take his or her chances. A passive optimist would wish a garden to just show up in the patch of ground. Who knows—a bird could drop seeds from overhead, a neighbor could just up and plant some stuff, perhaps seeds might fall from a plane. Maybe a random person passing by will feel the urge to sow something in the dirt. It could happen.

Passive hope has its literary and cultural precedents. In The Three Musketeers,Athos decides there’s no way he can come up with the money to equip himself for the next battle campaign so decides he might as well sit in his room and wait for the equipment to come to him. And, remarkably, it does, thanks to his active, generous (and it turns out, lucky) friend, d’Artagnan. And in one of my favorite Dr. Who episodes, Warrior’s Gate, as the characters search frantically for a way to avoid imminent collapse into a singularity, one of the characters advises the Doctor to do nothing. (This is largely because that character has taken matters in hand in a way the Doctor does not yet understand.) As disaster approaches the Doctor finally recognizes that sometimes doing nothing is appropriate, “if it’s the right sort of nothing.”

Passive hope has its literary and cultural precedents. In The Three Musketeers,Athos decides there’s no way he can come up with the money to equip himself for the next battle campaign so decides he might as well sit in his room and wait for the equipment to come to him. And, remarkably, it does, thanks to his active, generous (and it turns out, lucky) friend, d’Artagnan. And in one of my favorite Dr. Who episodes, Warrior’s Gate, as the characters search frantically for a way to avoid imminent collapse into a singularity, one of the characters advises the Doctor to do nothing. (This is largely because that character has taken matters in hand in a way the Doctor does not yet understand.) As disaster approaches the Doctor finally recognizes that sometimes doing nothing is appropriate, “if it’s the right sort of nothing.”There is indeed a time and a place for the Zen minimalism of doing the right sort of nothing. Most of the time, however, the Doctor and Athos are lively shapers of their fate. In fact, they only refrain from action the rare times when it is wiser to let other characters do the work. Though in Shakespeare in Love it’s a mystery to Henslowe how the play inevitably does go on, we see that the other characters struggle mightily to write a great play, cast it, rehearse it, scheme, organize, deal with reversals, push and strive to make the play a success.

As Kipling observed,

"Gardens are not made by singing ‘oh how beautiful’ and sitting in the shade.“

"Gardens are not made by singing ‘oh how beautiful’ and sitting in the shade.“ Most of the time someone must prepare the soil, plant some seeds and tend them with a certain amount of care. Most of the time if a community doesn’t manage its sewage and sanitation effectively, it is prone to outbreaks of disease. Most of the time if you use your chimney year after year without cleaning it, it will fill with soot and catch on fire. Some things one can trust to God or the universe to take care of, but other things are such a basic matter of cause and effect that God and the universe expect us human beings to stop being stupid and lazy and take care of them ourselves.

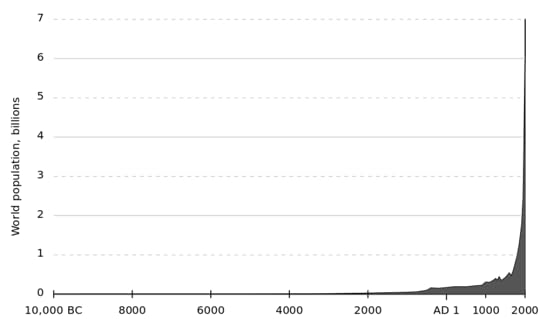

So where is this essay leading? In the last 150 years, with the advent of the unprecedented energy provided by fossil fuels, human population has exploded. We’ve made clever use of this energy to feed unprecedented numbers of people and raise standards of living for some to the levels of kings and queens of yore. In doing so we’ve spewed enough carbon, methane and other gases in the atmosphere that we are on track to transform our planet into a scorching hell. Why we lack urgency about this matter is because when it comes to carbon emissions, there is a time lag between cause and effect. This summer we are feeling the effects of carbon emitted fifty years ago. Unless we quickly get into the business of absorbing carbon rather than emitting it, the carbon we spew into our atmosphere this summer will be felt by our progeny fifty years hence.

So where is this essay leading? In the last 150 years, with the advent of the unprecedented energy provided by fossil fuels, human population has exploded. We’ve made clever use of this energy to feed unprecedented numbers of people and raise standards of living for some to the levels of kings and queens of yore. In doing so we’ve spewed enough carbon, methane and other gases in the atmosphere that we are on track to transform our planet into a scorching hell. Why we lack urgency about this matter is because when it comes to carbon emissions, there is a time lag between cause and effect. This summer we are feeling the effects of carbon emitted fifty years ago. Unless we quickly get into the business of absorbing carbon rather than emitting it, the carbon we spew into our atmosphere this summer will be felt by our progeny fifty years hence.  Human Population

Human PopulationIf we don't put the brakes on our collective carbon emissions, the earth’s temperature will rise 7 degrees F (4 degrees C) within our children’s lifetimes. This will be the hottest the earth has been in 30 million years. Half of all species presently living will go extinct, arable land will dwindle drastically, starvation and/or flooding will create hundreds of millions of refugees, and hundreds of millions will die from disease and/or starvation. This rise in temperature of 7 degrees F will likely trigger further feedback loops that will raise temperatures even further: to an 11 degree F rise within our grandchildren’s lifetimes, and to a 22 degree F rise by the year 2300. Ultimately, this will mean billions of humans dying with the earth so hot, survivors will be driven to live underground or in scattered, isolated areas still cool enough for human existence. If this is not a human extinction event, then it will be very close to it.

The future we are now creating for our children and grandchildren is bleak. Rapid climate change will bring about devastation and destruction on a scale worse than any war, any drought, or any plague humans have ever endured. The suffering and loss of life will be far worse than anything Hitler or Stalin ever dreamed of. Climate change on this scale is not just a possibility. If temperatures rise high enough to melt the methane frozen in the ocean and the arctic permafrost, it is a certainty. And methane has already begun to bubble up from the Arctic Ocean in plumes never before seen.

We can do nothing, of course, and hope for the best. Maybe an ice age will shortly set in and the earth will cool by itself. Maybe kindly aliens will arrive from outer space and save us. Maybe someone, somewhere will come up with some technology that will fix everything just fine. Surely if things were really bad our politicians would act responsibly and lead us down a sensible path. Why inconvenience ourselves, why spend money on energy sources that don’t destabilize the atmosphere, why change our lifestyles to reduce the amount of energy we consume, why go to the trouble of figuring out how to live in balance with our planet when there is a tiny chance some other force will step in and do the work for us?