Karen Lynn Allen's Blog, page 10

July 10, 2011

Publisher's Weekly Review of Beaufort 1849 (July 8, 2011)

Beaufort 1849

Karen Lynn Allen

Cabbages and Kings Press (www.cabbage-king.com), $13.95 trade paper (306p) ISBN 978-0-9671784-1-7

In this lively historical novel, set in Beaufort, S.C., at the apex of the town's antebellum period, prodigal son Jasper Wainwright returns to his family plantation after 12 years abroad to educate his kin about the evils of slavery. When he left Beaufort for Harvard University and world travel, Jasper was known as a hellion, savage drinker, and frequent duelist. Returning now—with an education and in the company of emancipated slave Spit Jim—to visit his cousin, Henry, at the lovely Villa D'Este, Jasper is stunned that Henry's niece, Cara Randall, is no longer the child he remembers, but a poised, intelligent, self-taught young woman keen to expand her mind and horizons. Having rejected numerous local suitors, Cara has no intention of marrying, and Jasper—widowed after a disastrous marriage—vows never to make the same mistake again. But both will be proven wrong, if the matchmaking Henry has his way. Cara is a singular, independent female in a culture of aristocratic entitlement, and she and Jasper aim to change the town's brutal system of slavery and bigotry in their own, converging ways. Charged with subtle period detail and boasting fully developed characters, Allen's work is sharp, smart, and well focused.

Link to Publisher's Weekly Review of Beaufort 1849

Karen Lynn Allen

Cabbages and Kings Press (www.cabbage-king.com), $13.95 trade paper (306p) ISBN 978-0-9671784-1-7

In this lively historical novel, set in Beaufort, S.C., at the apex of the town's antebellum period, prodigal son Jasper Wainwright returns to his family plantation after 12 years abroad to educate his kin about the evils of slavery. When he left Beaufort for Harvard University and world travel, Jasper was known as a hellion, savage drinker, and frequent duelist. Returning now—with an education and in the company of emancipated slave Spit Jim—to visit his cousin, Henry, at the lovely Villa D'Este, Jasper is stunned that Henry's niece, Cara Randall, is no longer the child he remembers, but a poised, intelligent, self-taught young woman keen to expand her mind and horizons. Having rejected numerous local suitors, Cara has no intention of marrying, and Jasper—widowed after a disastrous marriage—vows never to make the same mistake again. But both will be proven wrong, if the matchmaking Henry has his way. Cara is a singular, independent female in a culture of aristocratic entitlement, and she and Jasper aim to change the town's brutal system of slavery and bigotry in their own, converging ways. Charged with subtle period detail and boasting fully developed characters, Allen's work is sharp, smart, and well focused.

Link to Publisher's Weekly Review of Beaufort 1849

Published on July 10, 2011 08:54

July 7, 2011

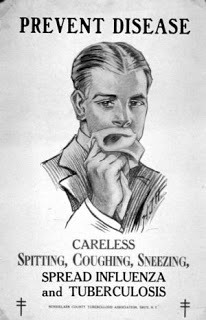

Spitting in the Wind, Past and Present

To spit in the wind is to attempt the impossible, a waste of one's time and energy, even if for a good reason or cause. In Beaufort 1849, Spit Jim accuses Jasper of this when, after reading an enlightened letter to the editor in the Charleston Courier, Jasper perceives a faint chance that the South might voluntarily transition away from a slave economy. Jim, justifiably antsy to leave the South, doesn't believe it for a second. "No one gives away wealth and power just because someone writes something sensible in a newspaper once in a while," he tells Jasper caustically and urges him to leave both the South and this futile hope behind as soon as possible.

But Jasper sees the tragedy that lies ahead if the South doubles down to defend its way of life. At the dawn of what is now known as the Second Industrial Revolution, he's aware that not only is public sentiment in the North and in Europe growing against slavery, but that the wealth and power of the world is beginning to swing heavily towards mechanization, industrialization, and energy supplied by coal. Try as it might, there will be no way for an agricultural South to maintain its economic and political parity with an industrialized North. Flush with immigrants and a growing middle class, the North is already vying for its economic system to prevail in the new territories and states as the nation expands. Further, as cries for secession mount in Beaufort, Jasper foresees the sheer impossibility of the North letting the South become a separate, hostile, militarily-powerful country stretching along its entire southern border, competing to annex land and resources. Because the South will be on the wrong side of economic (not to mention moral) history, Jasper realizes that in the coming fight for dominance the South is likely not only to lose the battle but to have its entire civilization crushed in the process.

Jim, born and raised a slave, is just fine with the prospect of the South's destruction. Jasper, however, argues that given the suffering that will likely result, they should try to head off the brewing violence by advocating for reform. And so he begins his impossible task of convincing Southern planters to voluntarily give up a portion of their wealth and control, turn slaves into citizens and willing participants in the economy, begin mechanized farming, and industrialize by creating mills to manufacture cotton into cloth for local markets. (The South will eventually do some approximation of all of this, but not until enduring great suffering, death and hardship, and even then the collapse of the Southern economy and widespread poverty will endure several generations.)

I don't think it's giving too much away to say that Jasper does not succeed in preventing the Civil War. Was he a fool even to try? Indeed, what are the odds that any one man could change the mind of an entire civilization? The reader of Beaufort 1849 knows Jasper is spitting in the wind from his very first attempt.

But if Jasper foresees disaster for the people he loves, isn't he morally obliged to do what he can to avert it? How hard should he persevere, how much should he sacrifice?

Imagine if you were to visit a beloved cousin you hadn't seen for a number of years. When you arrive, though he and his family appear quite prosperous, it soon becomes evident that the family is living beyond their means and that their prosperity is fueled by debt—credit cards, home equity withdrawls, no interest balloon payment loans, etc. As you hear about their recent Caribbean cruise, admire their remodeled kitchen, see the four new cars parked in the driveway, your feeling of impending doom for these people you love grows heavier and heavier. What do you do? Perhaps have a quiet talk with your cousin. And what will be the outcome? Most likely denial and perhaps a testy, "Mind your own business, everything's under control."

And what if your cousin lives in an entire town of people relying on ever-growing amounts of debt to maintain their lifestyle? What would your obligation be to change their behavior that is bound to make them poor, angry, unhappy and even desperate in the long run? If we like arguments, perhaps we might get into a few heated ones at a BBQ and make ourselves none too popular. For a subtler approach, we might offer hints that fall upon deaf ears. Perhaps we will be told that this way of life poses no problem, and how can we argue because, after all, it's worked up until now? Perhaps we are indeed Cassandra's, doomsters who want to frighten everyone into being miserable and giving up the good life because we can't stand to see others enjoying themselves.

Upton Sinclair once wrote, "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

Now what if your cousin made his living strip mining coal or marketing cigarettes? What if your cousin lived in early Nazi Germany and didn't seem troubled by the murders and disappearances because his mercantile trade was finally booming again? What if your cousin imported goods from Asia made by children and young teens for wages that barely kept them fed? Or what if your cousin lived in a slave economy, all his friends and neighbors owned slaves, and he used slaves to farm his fields?

I first saw the phrase, "Denial is not a river in Egypt," on a button worn by a NA (Narcotics Anonymous) member out with a bunch of compatriots on a day trip to Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay. The support and camaraderie that this group (who had likely been through hell) were giving each other was important, but so was the acknowledgement that change only occurs when one is willing and open to it. After one has identified and admitted the problem. People who don't believe they have a problem are unlikely to change. And people whose wealth and ease depend on a particular way of life are likely to defend that way of life rather than perceive problems with it. In fact, they are most likely to perceive problems with the person criticizing it.

I first saw the phrase, "Denial is not a river in Egypt," on a button worn by a NA (Narcotics Anonymous) member out with a bunch of compatriots on a day trip to Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay. The support and camaraderie that this group (who had likely been through hell) were giving each other was important, but so was the acknowledgement that change only occurs when one is willing and open to it. After one has identified and admitted the problem. People who don't believe they have a problem are unlikely to change. And people whose wealth and ease depend on a particular way of life are likely to defend that way of life rather than perceive problems with it. In fact, they are most likely to perceive problems with the person criticizing it.Now, what if the town living an unsustainable way of life (along whichever measure you wish—economic, moral, environmental, resource consumption, etc.) is not your cousin's but your own? What if it is not your town that is on a dangerous path, but your entire country? Your planet? Jasper has the option of leaving the South, and due to his struggles with alcoholism and commitments he's made to Jim, he knows he can't linger in Beaufort for long. In contrast, though most of us could probably change towns, countries would be difficult, and the planet impossible. Is pressing for change then more imperative even if deaf ears and anger seem to be the only result? Or is it wiser to hunker down, accept that the worst may indeed come, and put our energies towards preparing our families and those we love as best we can? As Dmitry Orlov observes, "Big changes happen slowly at first, then all at once." There may be less time to prepare than we think.

But what if "the worst" means the suffering and death of millions if not billions through drought and famine? What if "the worst" means our children will have available only a fraction of the energy and natural resources we currently enjoy? What if "the worst" means that half of all species currently on the planet will be driven to extinction? How bad does the future have to be to make inaction unbearable? Or is it all too clear that any attempt is simply spitting in the wind. A waste of time and energy. Pointless.

I don't have an answer to this quandary. Anyone who understands compound interest, can interpret charts and graphs, and has a basic understanding of science will have to weigh their ethical obligations against the practical realities of their lives. I have no doubt that each of us will feel called to different actions depending on our temperaments and life situations.

All stories involve problems. In comedies, through courage, ingenuity, cooperation, dramatic epiphany or perhaps plain luck, people manage to overcome their predicaments. In tragedies, they fail. The antebellum South was a tragedy. Rather than adapt to the demands of the time, the white populace risked everything to preserve an unsustainable way of life. The result was economic ruin and the collapse of their civilization.

Which are we living right now, comedy or tragedy? Do we need pluck, gumption and courage to heroically prevail against impossible odds? Or should we cultivate our ability to accept and adapt to the inescapable forces that history is already winding up to throw at us, however dreadful and harrowing they may be? I just don't know.

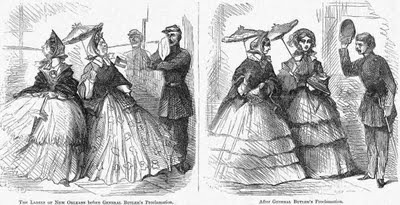

(A note on the first cartoon above: when occupying New Orleans in April of 1862, Major General Benjamin F. Butler issued a proclamation indicating that any woman who harassed a northern soldier by any show of contempt would be arrested as a prostitute. This didn't make him very popular in New Orleans, but it did cut down on the spitting.)

Published on July 07, 2011 17:57

June 20, 2011

Gideon Pillow: Coward, Liar and Scoundrel for the Ages (But, Oh, What a Name!)

The Glory of a Great NameIn the movie Shakespeare in Love, Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare are discussing Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate's Daughter when Marlowe suggests the character Mercutio. Later, Viola outlines the idea of Twelfth Night with a Duke Orsino. "Good name," Shakespeare says both times with admiration and a little envy, and I can entirely relate. As a writer, a good name can fill me with admiration, elation, and downright covetousness. And so it was when, researching the Civil War, I stumbled across the perfidious Gideon Pillow.

The Glory of a Great NameIn the movie Shakespeare in Love, Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare are discussing Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate's Daughter when Marlowe suggests the character Mercutio. Later, Viola outlines the idea of Twelfth Night with a Duke Orsino. "Good name," Shakespeare says both times with admiration and a little envy, and I can entirely relate. As a writer, a good name can fill me with admiration, elation, and downright covetousness. And so it was when, researching the Civil War, I stumbled across the perfidious Gideon Pillow.As I pondered the near perfection of the moniker I could only sigh deeply. Since the real Pillow could not be incorporated into Beaufort 1849, and since naming a fictional character after a real person alive at the time could cause confusion, there was no way to include the glorious name in my book. I had to be satisfied with calling one of my characters Gideon Pickens, a weak echo at best. But there is more to Mr. Gideon Pillow than just his name! As Henry Birch says in Beaufort 1849, "My, my. We have a complete bounder on our hands."

Born in Tennessee in 1806, Gideon Pillow practiced law in his home state as the partner of future president, James K Polk. Through his connections with Polk, he served as Brigadier General of the Tennessee Militia. Ten years later, when the Mexican-American War started up, Pillow deftly used political patronage to join the U.S. Army as a brigadier general. And then in 1847 President Polk promoted him to major general! Lesson learned: make friends with those who will ascend to high places.

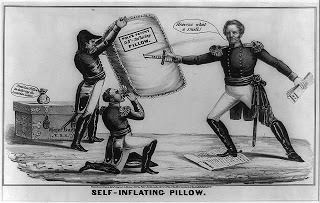

So far, so good. At the age of 41, Pillow appeared to be a rising star in the military. But then he made the mistake of crossing General Winfield Scott, commander of American forces in Mexico. Now, "Old Fuss and Feathers" Scott is considered by many historians to be one of the ablest generals in American military history. (He was also responsible for at least a portion of the terrible human toll during the Cherokee removal from Georgia, but that's another story.) After the major action of the war--action during which Pillow had altogether shown a great deal more incompetence than competence--Pillow felt he hadn't received enough recognition and glory. So under the pseudonym "Leonidas," he sent letters to the New Orleans Daily Delta and Picayune newspapers, as well the American Star and the Pittsburgh Post, crediting himself for recent American victories at Contreras and Churubusco. (Interesting to see that even in that day and age people worked the news media spin.)

Can't beat the caption aboveScott, however, knew very well that Pillow had done next to nothing to achieve those victories and that others deserved the credit. When the dastardly letters were exposed as Pillow's handiwork, Scott arranged for a court of inquiry into the matter. Believing Scott's actions politically motivated, President Polk came to the defense of his former law partner and recalled Scott to Washington. During the court of inquiry investigation, Pillow persuaded Major Archibald Burns to claim authorship of the letters and publicly take the fall for him. It was not widely believed however, and Pillow was discharged from the army all the same.

Can't beat the caption aboveScott, however, knew very well that Pillow had done next to nothing to achieve those victories and that others deserved the credit. When the dastardly letters were exposed as Pillow's handiwork, Scott arranged for a court of inquiry into the matter. Believing Scott's actions politically motivated, President Polk came to the defense of his former law partner and recalled Scott to Washington. During the court of inquiry investigation, Pillow persuaded Major Archibald Burns to claim authorship of the letters and publicly take the fall for him. It was not widely believed however, and Pillow was discharged from the army all the same.Said Scott in his memoirs, Pillow was "amiable and possessed of some acuteness, but the only person I have ever known who was wholly indifferent in the choice between truth and falsehood, honesty and dishonesty:—ever as ready to attain an end by the one as the other, and habitually boastful of acts of cleverness at the total sacrifice of moral character."

Always ambitious, Pillow went on to try for the nomination for vice president but failed twice, in 1852 and again in 1856. His next shot for public glory would be the Civil War.

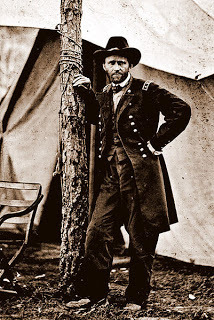

When the war began, Pillow joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general in the Western Theater. He is best remembered for two battles, the first being the Battle of Fort Donelson. Fort Donelson was a Confederate stronghold in Tennessee that protected the vital manufacturing and arsenal city of Nashville. The battle turned out to be Ulysses S. Grant's first big success, and indeed was a vital victory for the North at a time when the Union army was showing little progress at all.

Now Fort Donelson was under the command of Brigadier General John B. Floyd, a political appointee who, although he had been Secretary for War for the United States right up until nearly the Secession, had no actual experience in conducting war. Second-in-command was our friend, Gideon Pillow, who in theory had experience in the Mexico, but as we know was really a fraud who tended to talk big and do little.

Confederate troops at Fort Donelson numbered 18,000, whereas Grant had about 25,000 Union troops at his disposal. To capture a fortified position generally took a three to one advantage in numbers, so you can see Grant had almost no business even considering attacking Fort Donelson. But fresh from his victory over nearby Fort Henry (mostly due to the badly-engineered Fort Henry conveniently flooding the Confederates out) Grant was confident of success at Fort Donelson as well. It turns out this confidence was largely due to his knowledge that Gideon Pillow was in command inside that fort. Said Grant in his memoirs:

Pillow deflator"I had known General Pillow in Mexico, and judged that with any force, no matter how small, I could march up to within gunshot of any intrenchments he was given to hold. I said this to the officers of my staff at the time. I knew that Floyd was in command, but he was no soldier, and I judged that he would yield to Pillow's pretensions."

Pillow deflator"I had known General Pillow in Mexico, and judged that with any force, no matter how small, I could march up to within gunshot of any intrenchments he was given to hold. I said this to the officers of my staff at the time. I knew that Floyd was in command, but he was no soldier, and I judged that he would yield to Pillow's pretensions."And Pillow did not disappoint! And yet to be fair, Pillow did actually achieve success in battle before he managed to completely screw it up. With the fort surrounded in large part by Union troops, the Confederate officers knew things looked bad for them, so at dawn Pillow directed an assault of 10,000 men into the unprotected right flank of the Union line in an attempt to open up an escape route. This way they would cede the fort but not lose the men.

Surprisingly, luck went with him. Pillow had a massive force filled with talented men, among them Nathan Bedford Forrest, and he had the advantage of surprise. Not expecting the Confederates to take action that morning, Grant was away consulting with a gunboat officer too wounded to come and make a report to him. Other than telling his underlings to stand their ground, he didn't leave much in the way of instructions, so when Pillow's forces attacked, they found unorganized resistance, brigadier generals unwilling to help each other without explicit orders from Grant, and troops who were curiously clueless about how to resupply themselves with ammunition even when there was plenty lying about in boxes on the ground.

After a few hours of heavy fighting, the Confederates pushed through and the escape route was clear! The Confederate troops fought with backpacks of three days provisions on their backs. They were ready to head to south to safety.

The heat of battleIt was right about then that Grant returned from his visit to his wounded officer. Much to his surprise he found a battle going on, a battle in which his side was being routed. Wounded and demoralized men were everywhere; noise, smoke and chaos abounded. Characteristic of Grant, he didn't freak out. (No matter how bad things were, Grant never freaked out, a good quality in a general.) He quickly figured out that the Confederates were pressing for escape not a combat victory, he determined where they would be weakest, and he started giving orders. From his memoirs: "I directed Colonel Webster to ride with me and call out to the men as we passed: 'Fill your cartridge-boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so.' This acted like a charm. The men only wanted some one to give them a command."

The heat of battleIt was right about then that Grant returned from his visit to his wounded officer. Much to his surprise he found a battle going on, a battle in which his side was being routed. Wounded and demoralized men were everywhere; noise, smoke and chaos abounded. Characteristic of Grant, he didn't freak out. (No matter how bad things were, Grant never freaked out, a good quality in a general.) He quickly figured out that the Confederates were pressing for escape not a combat victory, he determined where they would be weakest, and he started giving orders. From his memoirs: "I directed Colonel Webster to ride with me and call out to the men as we passed: 'Fill your cartridge-boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so.' This acted like a charm. The men only wanted some one to give them a command."He had one general attack the enemy's west side, the other the enemy's east. And then Grant had his turn of luck in the expected form of Pillow's bad judgment. Just when the Confederates had created their escape route, and indeed, were halfway to leaving, for some incomprehensible reason Pillow decided to regroup and resupply his troops before pushing forward. To the amazement of all he ordered his troops back into their trenches, and all advantages gained by the Confederates that morning were lost. Grant quickly exploited the opening given to him, and by the end of the day the Union army was poised to take the fort.

That night was a bad one for the Confederate leadership. General Floyd was edgy. Having committed what amounted to treason as U.S. Secretary of War (shipping arms from northern armories to southern ones to better position the South when Secession came was just one example of why the North might like to hang him), he decided to skedaddle out while the going was good and offered the command of the 18,000 troops to his second-in-command, Gideon Pillow. But Pillow then decided that it was also too dangerous for him to be captured for reasons known only to himself. So he handed the command to third-in-command, Brigadier General Simon P. Buckner who accepted responsibility for the welfare of the troops, and Floyd and Pillow fled in the dark of night. Nathan Bedford Forrest, furious at the general level of incompetence and stupidity, said, "I did not come here to surrender my command," and stormed out. He also left during the night, escaping with his cavalry of 700 by mucking through swamps and fording swollen creeks to the south.

Though the next morning Grant would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender from Bruckner, he and Bruckner were old buddies from West Point and the Mexican war. They discussed Pillow's flight the previous night, and how Pillow had expressed concern that his capture would be a disaster for the Southern cause.

"He thought you'd rather get hold of him than any other man in the Southern Confederacy," Buckner told Grant."Oh," replied Grant, "if I had got him, I'd let him go again. He will do us more good commanding you fellows."

The fall of Fort Donelson and the loss of so many men was difficult for Pillow to spin, though he did try. But his next battle, the Battle of Stones River, where Major General Breckinridge found Pillow cowering behind a tree and had to order him forward, spelled the end for Pillow's combat assignments. Though he went on to administrative positions in the Confederate army (where he could do less damage), he had successfully earned for all time the distinction of being one of the worst generals in American history.

Published on June 20, 2011 22:28

June 12, 2011

Five Simple Technologies to Improve Your Family's Resiliency

With this post I'm switching to another subject that, when I'm not writing fiction, I spend time researching and thinking about: energy and its sources and uses. Since there are many connections between energy and water (energy is used to pump and transport water, and in the case of hydroelectricity, water is used to make energy), when I'm energy blogging I'll sometimes talk about water was well.

With this post I'm switching to another subject that, when I'm not writing fiction, I spend time researching and thinking about: energy and its sources and uses. Since there are many connections between energy and water (energy is used to pump and transport water, and in the case of hydroelectricity, water is used to make energy), when I'm energy blogging I'll sometimes talk about water was well.Whether it's due to peak oil or a hurricane, war in the Middle East or a heat wave, there are many factors that could create spot shortages in energy, could cause prices to rise sharply in the short term, or could gradually but inexorably inflate energy costs in the long term. Although different energy forms are not completely interchangeable (for example, electricity cannot easily substitute for oil in the US without major upgrades in our electrical grid and transportation infrastructure) they are fungible enough that a shortage of any one of them will cause prices to rise for all. Even without natural disasters or wars, I expect short term we will see gasoline prices increase (unless the economy tanks sharply, pulling commodity prices down with it), and longer term we will see electricity prices rise significantly for peak hour use (i.e. periods of max air conditioning).

So, to make your family resilient either in the face of a temporary shortage or a longer-term escalation in price, here are some simple, highly cost effective technologies you can employ. Though some may seem laughably obvious, the majority of Americans employ only one or two, and often even those ineffectively.

1) Attic sealing and insulation. Very simple, fairly cheap, and yet not nearly as widely used as it should be. It's important to remember that there's a difference between movement of heat and movement of air. Insulation prevents movement of heat but if there are gaps, holes, etc, between the lower floor and the attic, it won't prevent air movement. At any temperature, air moving across the skin makes us feel cooler than we otherwise would, so sealing up these holes and gaps is a good idea. If you already have some amount of insulation, someone may need to go into your attic, pull back that insulation, look for gaps and then seal them with caulk, expanding foam, or rigid foam board insulation. Then you (or a service) can add insulation until it's about knee deep. If your house is now drafty and poorly insulated, you can save as much as ½ to 1/3 of your monthly winter heating costs. Remember also that heat wants to rise more than it wants to travel horizontally, so insulating your attic is more important than replacing single pane windows unless they're very leaky and drafty.

1) Attic sealing and insulation. Very simple, fairly cheap, and yet not nearly as widely used as it should be. It's important to remember that there's a difference between movement of heat and movement of air. Insulation prevents movement of heat but if there are gaps, holes, etc, between the lower floor and the attic, it won't prevent air movement. At any temperature, air moving across the skin makes us feel cooler than we otherwise would, so sealing up these holes and gaps is a good idea. If you already have some amount of insulation, someone may need to go into your attic, pull back that insulation, look for gaps and then seal them with caulk, expanding foam, or rigid foam board insulation. Then you (or a service) can add insulation until it's about knee deep. If your house is now drafty and poorly insulated, you can save as much as ½ to 1/3 of your monthly winter heating costs. Remember also that heat wants to rise more than it wants to travel horizontally, so insulating your attic is more important than replacing single pane windows unless they're very leaky and drafty. 2) Ceiling fans. As stated before, at any temperature, movement of air across the skin makes us feel cooler than we otherwise would. So in the summer months, ceiling fans are a great way to combat heat using far, far less energy than air conditioning units. In South Carolina I noticed many houses and shops use both air conditioning and ceiling fans so that the air conditioning can be set at a much higher level—say 80 degrees—and still be quite comfortable. A ceiling fan can save you as much as 40% of your summer cooling costs. Ceiling fans are more energy efficient than floor fans, but they are also more work to install properly.

2) Ceiling fans. As stated before, at any temperature, movement of air across the skin makes us feel cooler than we otherwise would. So in the summer months, ceiling fans are a great way to combat heat using far, far less energy than air conditioning units. In South Carolina I noticed many houses and shops use both air conditioning and ceiling fans so that the air conditioning can be set at a much higher level—say 80 degrees—and still be quite comfortable. A ceiling fan can save you as much as 40% of your summer cooling costs. Ceiling fans are more energy efficient than floor fans, but they are also more work to install properly. 3) Programmable thermostats. Don't heat or cool your house when you're not there to benefit! And at night use a blanket or a ceiling fan to help warm or cool you to a comfortable temperature. Programmable thermostats cost about $35. They are not all that difficult to install or program, though, sadly, 40% of Americans who have programmable thermostats never actually program them. (Ouch!) During the winter, take advantage of this simple technology to a.) automatically turn down the heat when you're gone to 55 degrees, (most pets can do ok with 61 degrees), b.) turn the heat down at night to whatever temperature keeps you comfortable under a couple blankets, and c.) turn on the heat an hour before you get up so the house is pleasant again. You can experiment with the settings that work best for you, but heating the house up to 70 degrees 24/7 costs you way more than you need. In the winter, our house generally varies between 55 degrees at night and 63 degrees during the day, but I'm willing to wear lots of wool. (I also encourage my kids to use those other little technologies called sweaters and slippers.) In the summer, leave the air conditioning off until an hour before you're going to return home. Or you could leave your blinds closed during the day and when you come home, open up the house to the cooler evening temperatures and use a whole house fan to push the hot air out and pull the cool air in. Another low tech tip—plant deciduous trees on the south side of your house that will shade the house in the summer and let in warming sunlight in the winter.

3) Programmable thermostats. Don't heat or cool your house when you're not there to benefit! And at night use a blanket or a ceiling fan to help warm or cool you to a comfortable temperature. Programmable thermostats cost about $35. They are not all that difficult to install or program, though, sadly, 40% of Americans who have programmable thermostats never actually program them. (Ouch!) During the winter, take advantage of this simple technology to a.) automatically turn down the heat when you're gone to 55 degrees, (most pets can do ok with 61 degrees), b.) turn the heat down at night to whatever temperature keeps you comfortable under a couple blankets, and c.) turn on the heat an hour before you get up so the house is pleasant again. You can experiment with the settings that work best for you, but heating the house up to 70 degrees 24/7 costs you way more than you need. In the winter, our house generally varies between 55 degrees at night and 63 degrees during the day, but I'm willing to wear lots of wool. (I also encourage my kids to use those other little technologies called sweaters and slippers.) In the summer, leave the air conditioning off until an hour before you're going to return home. Or you could leave your blinds closed during the day and when you come home, open up the house to the cooler evening temperatures and use a whole house fan to push the hot air out and pull the cool air in. Another low tech tip—plant deciduous trees on the south side of your house that will shade the house in the summer and let in warming sunlight in the winter.

4) Bicycles, racks, and panniers. The bicycle is one of the most efficient machines mankind has ever devised. It takes less energy per mile to go by bicycle than by any other mode of transport, including walking. For most terrains it's easy to cover a mile by bicycle in six or seven minutes. For distances under two miles, when you factor in time to walk and park your car, it's generally as fast to bicycle as drive. And you don't need to be Lance Armstrong kitted out in Lycra! You can wear regular clothes, ride an upright bicycle at a leisurely pace and be no sweatier or tired than if you'd spent the minutes strolling your neighborhood. To make your bicycle useful for errands, get a rack with panniers. This will allow you to carry two grocery bags full of stuff with ease—the load will be on your bicycle, not on your back! If, like me, you live in an area with hills, consider an electric bicycle. These are substantially more expensive but they essentially make the hills flat and can be an excellent car substitute if an oil shortage arises.

4) Bicycles, racks, and panniers. The bicycle is one of the most efficient machines mankind has ever devised. It takes less energy per mile to go by bicycle than by any other mode of transport, including walking. For most terrains it's easy to cover a mile by bicycle in six or seven minutes. For distances under two miles, when you factor in time to walk and park your car, it's generally as fast to bicycle as drive. And you don't need to be Lance Armstrong kitted out in Lycra! You can wear regular clothes, ride an upright bicycle at a leisurely pace and be no sweatier or tired than if you'd spent the minutes strolling your neighborhood. To make your bicycle useful for errands, get a rack with panniers. This will allow you to carry two grocery bags full of stuff with ease—the load will be on your bicycle, not on your back! If, like me, you live in an area with hills, consider an electric bicycle. These are substantially more expensive but they essentially make the hills flat and can be an excellent car substitute if an oil shortage arises. 5) Water Filters. Why pay for bottled water if you can filter water from your tap that tastes as good for a fraction of the cost? Having a good filter on hand also means you can tap many sources of water in case of an emergency (say an earthquake, hurricane or tornado) that shuts down the water supply system. There are many filters on the market--one I like is the Big Berkey water filter. From their website:

5) Water Filters. Why pay for bottled water if you can filter water from your tap that tastes as good for a fraction of the cost? Having a good filter on hand also means you can tap many sources of water in case of an emergency (say an earthquake, hurricane or tornado) that shuts down the water supply system. There are many filters on the market--one I like is the Big Berkey water filter. From their website:This system removes pathogenic bacteria, cysts and parasites entirely and extracts harmful chemicals such as herbicides, pesticides, VOCs, organic solvents, radon 222 and trihalomethanes. It also reduces nitrates, nitrites and unhealthy minerals such as lead and mercury. This system is so powerful it can remove food coloring from water without removing the beneficial minerals your body needs.Even if you don't use a filter to reduce chemicals in your normal drinking water, in a crisis it might be handy to turn water from a rain barrel, creek or pond into safe drinking water. For some reason, Berkey doesn't ship to California or Iowa. (I think it has to do with these state's laws.) Remember, as gasoline prices go up, any liquid shipped by truck is bound to increase in price as the shipping weight involved is substantial. If you really like carbonated beverages, you can get a home carbonator like this for around $100.

So five simple, inexpensive technologies that can vastly improve your family's ability to weather an emergency or save you nearly their upfront cost the first year by reducing your energy (or bottled water) bills. I hope you'll give them a try.

Published on June 12, 2011 13:44

June 1, 2011

Head in the Beaufort Clouds

Carolina skyIt rained in San Francisco yesterday on the last day of May. It rained again today. If you lived in San Francisco you would know that it never rains here this time of year. Nor in May do we get billowing, puffy clouds with dark undersides that roll northwest as if looking for trouble in the Sierras. Even though the sun sometimes shines through the downpour, one begins to despair of summer at all. And so on these obstinately cool, winter-like days when my strawberries are unlikely to ripen and bike rides are sodden excursions, my thoughts turn to South Carolina--Beaufort, to be specific--where it did not rain yesterday and the temperature reached 97 degrees. Now there's summer for you, even if the solstice has yet to arrive.

Carolina skyIt rained in San Francisco yesterday on the last day of May. It rained again today. If you lived in San Francisco you would know that it never rains here this time of year. Nor in May do we get billowing, puffy clouds with dark undersides that roll northwest as if looking for trouble in the Sierras. Even though the sun sometimes shines through the downpour, one begins to despair of summer at all. And so on these obstinately cool, winter-like days when my strawberries are unlikely to ripen and bike rides are sodden excursions, my thoughts turn to South Carolina--Beaufort, to be specific--where it did not rain yesterday and the temperature reached 97 degrees. Now there's summer for you, even if the solstice has yet to arrive. A view to what wasThere was a time, a stretch of two years, when my thoughts often turned to Beaufort. I thought of Beaufort while sitting at my kitchen table, while doing the Tai Chi form, while driving across San Francisco to pick my daughter up from school. I remembered how the light filtered through the Spanish moss, how the river ebbed and flowed with the tide, how the cord grass swayed in the wind. I ruminated over the masses of oysters growing on the city's piers, the daytime's suffocating heat, the evening's lively breeze. When I shut my eyes I saw the stately houses, the ancient arching trees. My thoughts were not so much of Beaufort as it exists, but of Beaufort as it was, though the present Beaufort was my signpost to the former age.

A view to what wasThere was a time, a stretch of two years, when my thoughts often turned to Beaufort. I thought of Beaufort while sitting at my kitchen table, while doing the Tai Chi form, while driving across San Francisco to pick my daughter up from school. I remembered how the light filtered through the Spanish moss, how the river ebbed and flowed with the tide, how the cord grass swayed in the wind. I ruminated over the masses of oysters growing on the city's piers, the daytime's suffocating heat, the evening's lively breeze. When I shut my eyes I saw the stately houses, the ancient arching trees. My thoughts were not so much of Beaufort as it exists, but of Beaufort as it was, though the present Beaufort was my signpost to the former age. The way lamps used to be lit

The way lamps used to be lit

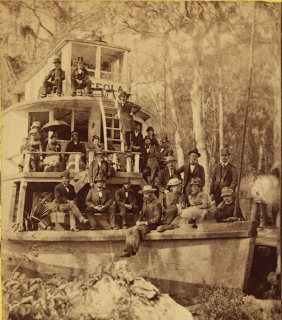

The way to get aroundThough I could visit Beaufort (and I did) I couldn't visit 1849, at least not in person. I read books and books, both factual accounts and narratives from the period, in my quest to digest the values and the language, the customs and the manners, the technologies, cuisine, and cultural reference points of the era. Armed with legions of details, I then had to think through my characters, how they moved through this world over a century and a half ago, parsing what would have been important to them and why. In 1849 women still wore petticoats because hoop skirts had yet to come into fashion. This made their clothing heavier and hotter than a decade later. In 1849, whale oil was still used to fuel lamps rather than kerosene. In fact, the world had just about reached peak whales and peak whale oil, although no one then yet knew it. In 1849 laundry was a heavy, hot affair and no one with money did their own. In addition, since dyes were not colorfast, most top layers of clothing were brushed, not washed, preferably by a servant. In 1849 roads in the South were poor and trains not yet prevalent, so for a town like Beaufort, being on a steamer route connoted a nearly cosmopolitan connection to the exterior world.

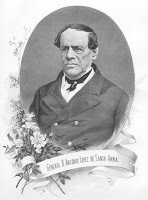

The way to get aroundThough I could visit Beaufort (and I did) I couldn't visit 1849, at least not in person. I read books and books, both factual accounts and narratives from the period, in my quest to digest the values and the language, the customs and the manners, the technologies, cuisine, and cultural reference points of the era. Armed with legions of details, I then had to think through my characters, how they moved through this world over a century and a half ago, parsing what would have been important to them and why. In 1849 women still wore petticoats because hoop skirts had yet to come into fashion. This made their clothing heavier and hotter than a decade later. In 1849, whale oil was still used to fuel lamps rather than kerosene. In fact, the world had just about reached peak whales and peak whale oil, although no one then yet knew it. In 1849 laundry was a heavy, hot affair and no one with money did their own. In addition, since dyes were not colorfast, most top layers of clothing were brushed, not washed, preferably by a servant. In 1849 roads in the South were poor and trains not yet prevalent, so for a town like Beaufort, being on a steamer route connoted a nearly cosmopolitan connection to the exterior world.  CrushedIn 1849, most Americans (Thoreau one of the few excepted) felt pride in the crushing of Santa Anna and the Mexican army and saw nothing amiss in forcing Mexico to sell of a third of its land at a cut-rate price to its stronger neighbor. In 1849, gold was practically leaping into the hands of miners in California, Chopin was writing his last waltzes in Europe, and the engines of the industrial North were revving up, even if the South couldn't hear their echoes yet. In 1849, the last good president had been Andrew Jackson a dozen years before, John Calhoun (South Carolina's "cast iron" senator) was on his last legs, and manifest destiny wasn't no longer a doctrine but an achievement in progress. In 1849, things were changing in America with more speed and uncertainty than the average citizen was comfortable with. Though the last five sentences are all gross generalizations, it gives broad brushstrokes of the American 1849 mindset. But what their memories would have consisted of—that was harder to reconstruct.

CrushedIn 1849, most Americans (Thoreau one of the few excepted) felt pride in the crushing of Santa Anna and the Mexican army and saw nothing amiss in forcing Mexico to sell of a third of its land at a cut-rate price to its stronger neighbor. In 1849, gold was practically leaping into the hands of miners in California, Chopin was writing his last waltzes in Europe, and the engines of the industrial North were revving up, even if the South couldn't hear their echoes yet. In 1849, the last good president had been Andrew Jackson a dozen years before, John Calhoun (South Carolina's "cast iron" senator) was on his last legs, and manifest destiny wasn't no longer a doctrine but an achievement in progress. In 1849, things were changing in America with more speed and uncertainty than the average citizen was comfortable with. Though the last five sentences are all gross generalizations, it gives broad brushstrokes of the American 1849 mindset. But what their memories would have consisted of—that was harder to reconstruct. GranddaddiesWhat I gleaned from my reading was that historical cultural memory of the era proudly focused on the glorious revolution that their grandfathers had achieved and the momentous first-of-its-kind government they'd subsequently created. In 1849 these grandchildren knew they had inherited something grand but were growing uneasy as to whether it was a legacy they could keep. The Bible, the Magna Carta, ancient Rome, and ancient Greece were their touchstones. George Washington and Mr. Jefferson had been known (or at least seen) by men and women still alive. In 1849, most people were aware that life was less dangerous, brutal and short than it had been for their forefathers, and they were grateful. The Civil War and its awful grinding slaughter did not lurk unpleasantly in their past. At that point the pain involved in rending the nation in two was not something they could conceive of. Though certainly adept enough at hangings, whippings and other brutality, they were also incapable of imagining the systematized factory barbarity that the twentieth century achieved at Auschwitz that still haunts our collective memory today. We can envy their innocence, but events that should have featured prominently in their historic conscience—the Trail of Tears, the horrific sea passage of the slave trade—most seemed to dispose of with a shrug.

GranddaddiesWhat I gleaned from my reading was that historical cultural memory of the era proudly focused on the glorious revolution that their grandfathers had achieved and the momentous first-of-its-kind government they'd subsequently created. In 1849 these grandchildren knew they had inherited something grand but were growing uneasy as to whether it was a legacy they could keep. The Bible, the Magna Carta, ancient Rome, and ancient Greece were their touchstones. George Washington and Mr. Jefferson had been known (or at least seen) by men and women still alive. In 1849, most people were aware that life was less dangerous, brutal and short than it had been for their forefathers, and they were grateful. The Civil War and its awful grinding slaughter did not lurk unpleasantly in their past. At that point the pain involved in rending the nation in two was not something they could conceive of. Though certainly adept enough at hangings, whippings and other brutality, they were also incapable of imagining the systematized factory barbarity that the twentieth century achieved at Auschwitz that still haunts our collective memory today. We can envy their innocence, but events that should have featured prominently in their historic conscience—the Trail of Tears, the horrific sea passage of the slave trade—most seemed to dispose of with a shrug. No looking back1849 in America was not a time of regret for past failings or longing for what was. That would come later, at least for the South. Instead it was a time of expansion and optimism, of growth and domination. For those growing cotton, it was a time of great wealth. For centuries now America, priding itself on its optimism and expansion--geographically, economically, and otherwise--has been little interested in all but the most superficial glances backwards. Perhaps those who are confident of the future always have little patience for history. Perhaps like a shark we must always swim forward or perish.

No looking back1849 in America was not a time of regret for past failings or longing for what was. That would come later, at least for the South. Instead it was a time of expansion and optimism, of growth and domination. For those growing cotton, it was a time of great wealth. For centuries now America, priding itself on its optimism and expansion--geographically, economically, and otherwise--has been little interested in all but the most superficial glances backwards. Perhaps those who are confident of the future always have little patience for history. Perhaps like a shark we must always swim forward or perish.  Salty pillar gets a good lookPerhaps only those who are uncertain about what lies ahead try to see what the past can tell us. Like Lot's wife, they are the ones who, with wavering step, turn back to glimpse the fire and brimstone. For this momentary act of defiance, Lot's wife (she never even gets her own name) is transformed into a pillar of salt. But the Bible gives us the story of Lot and his doomed cities precisely to encourage us to look back, to reflect, to learn. Sometimes looking back, even to the summer of 1849, is a means of swimming forward.

Salty pillar gets a good lookPerhaps only those who are uncertain about what lies ahead try to see what the past can tell us. Like Lot's wife, they are the ones who, with wavering step, turn back to glimpse the fire and brimstone. For this momentary act of defiance, Lot's wife (she never even gets her own name) is transformed into a pillar of salt. But the Bible gives us the story of Lot and his doomed cities precisely to encourage us to look back, to reflect, to learn. Sometimes looking back, even to the summer of 1849, is a means of swimming forward.

Published on June 01, 2011 14:18

May 23, 2011

Why Remember the Civil War?

"The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."--Abraham LincolnI have ancestors that fought on both sides of the U.S. Civil War. My mother's kin fought for the Union and my father's for the Confederacy. Generations later, both families made it to California, one via Kansas, the other by way of Oklahoma. Both came to the Golden State during the Depression, and it was this historic event that I heard the rumbling echoes of as I grew up. The tales of my childhood were of how my great-grandmother, a widow, would have starved if my grandfather hadn't sent her money home from the WPA camp. And how my grandmother, an independent woman working as a nurse until she was in her thirties, proudly saved a sizeable sum of money before she was married.

If there were stories about battles in my family, they were about my grandfather's stint on Okinawa (horrific.) I knew nothing of Manassas or Fredericksburg, and I only grew aware of Gettysburg when required to memorize the Gettysburg Address in school. (Thank you, Lincoln, for keeping it short!) Remarkably, I covered the American Revolution four times in my academic career, but never the Civil War. I had a vague notion that the South had slaves and that the slaves escaped on railroads. Since slavery was bad, the North had been in the right and so of course won the war.

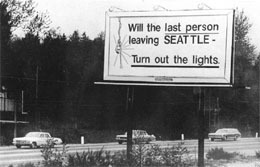

Exodus isn't just a book in the BibleI was six and a half when I heard "a king" had been killed (I asked what country he was king of), a murder shortly to be followed by that of Bobby Kennedy. It was the same year my parents continued their own parents' migration by leaving California for Washington State. San Francisco's summer of love in 1967 had been too much for them, and they fled for the calmer climes of suburban Seattle. Little did they know that a mere three years later the bottom would drop out of Boeing and the Seattle economy, creating a exodus so enormous that a billboard near Sea-Tac airport read, "Will the last person leaving Seattle, turn out the lights." That economic recession colored my entire childhood and, in a way, shaped most of my twenties, though at the time I was relatively unaware how history could be an active participant in a person's destiny.

Exodus isn't just a book in the BibleI was six and a half when I heard "a king" had been killed (I asked what country he was king of), a murder shortly to be followed by that of Bobby Kennedy. It was the same year my parents continued their own parents' migration by leaving California for Washington State. San Francisco's summer of love in 1967 had been too much for them, and they fled for the calmer climes of suburban Seattle. Little did they know that a mere three years later the bottom would drop out of Boeing and the Seattle economy, creating a exodus so enormous that a billboard near Sea-Tac airport read, "Will the last person leaving Seattle, turn out the lights." That economic recession colored my entire childhood and, in a way, shaped most of my twenties, though at the time I was relatively unaware how history could be an active participant in a person's destiny. Dress like MarthaAh, history. We can't do anything about it. It's dead. It's gone. Doesn't remembering just evoke pain and recrimination? Why not live and let live, go forward afresh and new? This year, 2011, is the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. It is nothing compared to the bicentennial of our country's founding. Now that was a party. 1976—seems like yesterday. Stars and stripes were everywhere, on every product, in every ad. Schoolhouse Rock had Saturday morning cartoons about it, and people even sewed their own Martha Washington dresses from Butterick patterns.

Dress like MarthaAh, history. We can't do anything about it. It's dead. It's gone. Doesn't remembering just evoke pain and recrimination? Why not live and let live, go forward afresh and new? This year, 2011, is the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. It is nothing compared to the bicentennial of our country's founding. Now that was a party. 1976—seems like yesterday. Stars and stripes were everywhere, on every product, in every ad. Schoolhouse Rock had Saturday morning cartoons about it, and people even sewed their own Martha Washington dresses from Butterick patterns.

"I'm just a bill . . ."The Declaration of Independence was an unequivocal milestone in human achievement, and our war of revolution (unlike the recent humiliation in Vietnam) was one we could all feel good about. We won. We were right, and through our courage, fortitude and wisdom, we established a precedent for the world to follow. The French fleet who'd really signed the deal for us weren't mentioned much, and Loyalists who bet on the wrong horse and had to leave everything behind to flee to Canada weren't brought up at all. The subsequent near annihilation of the native peoples of the continent didn't get much play, nor did how the legitimization of slavery by the Constitution and our Founding Fathers was a betrayal of the country's founding precepts, not to mention it left a huge mess for following generations to resolve. No, the American Revolution was crystalline in its fife and drum purity and unambiguous goodness.

"I'm just a bill . . ."The Declaration of Independence was an unequivocal milestone in human achievement, and our war of revolution (unlike the recent humiliation in Vietnam) was one we could all feel good about. We won. We were right, and through our courage, fortitude and wisdom, we established a precedent for the world to follow. The French fleet who'd really signed the deal for us weren't mentioned much, and Loyalists who bet on the wrong horse and had to leave everything behind to flee to Canada weren't brought up at all. The subsequent near annihilation of the native peoples of the continent didn't get much play, nor did how the legitimization of slavery by the Constitution and our Founding Fathers was a betrayal of the country's founding precepts, not to mention it left a huge mess for following generations to resolve. No, the American Revolution was crystalline in its fife and drum purity and unambiguous goodness. Sesquicentennial SplendorCompare that national extravaganza to this year. Now, it's true that a sesquicentennial is fundamentally less exciting than a bicentennial—heavens, the word itself is a pain to pronounce. So what we have are a few new books out, some magazine and newspaper articles on the Civil War, some low-key, local events. But I would posit that this is at least partly because we're not sure how to view this war anymore. What used to be clear is murky these days. The South's bitterness has mellowed and developed a different patina; the North's righteousness has turned into something more ambiguous and wistful. Yes, the Civil War ended slavery, but we're starting to remember that that had not been its original intent. Yes, the war saved the Union, but if the Constitution had been a contract, both sides had violated its terms, and who was to blame that there was no exit clause? And we're more aware these days that in every battle, one side's victory meant the others side's death and maiming, and as such they can't be celebrated, only mourned.

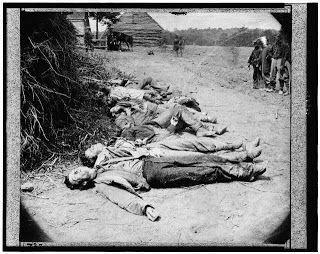

Sesquicentennial SplendorCompare that national extravaganza to this year. Now, it's true that a sesquicentennial is fundamentally less exciting than a bicentennial—heavens, the word itself is a pain to pronounce. So what we have are a few new books out, some magazine and newspaper articles on the Civil War, some low-key, local events. But I would posit that this is at least partly because we're not sure how to view this war anymore. What used to be clear is murky these days. The South's bitterness has mellowed and developed a different patina; the North's righteousness has turned into something more ambiguous and wistful. Yes, the Civil War ended slavery, but we're starting to remember that that had not been its original intent. Yes, the war saved the Union, but if the Constitution had been a contract, both sides had violated its terms, and who was to blame that there was no exit clause? And we're more aware these days that in every battle, one side's victory meant the others side's death and maiming, and as such they can't be celebrated, only mourned. Dead Americans618,000 Americans died in the Civil War war, 68,000 of them African-American. That was the cost of that war. Though few understood it at the time, those 618,000 husbands, sons, and brothers were consumed by an epic battle of industrialization wrestling agriculture for the reins of the North American continent. Which is not to say the Civil War was not about slavery—it was. But it was also about the deal that had been brokered by the Constitution that had been unraveling for decades. It was about changing technologies and energy sources, and how society necessarily had to evolve as a result. It was about immigration and conflicting, competing economic models. And, like most wars, underneath it all it was about money and power and who would possess them.

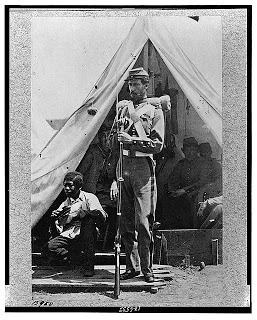

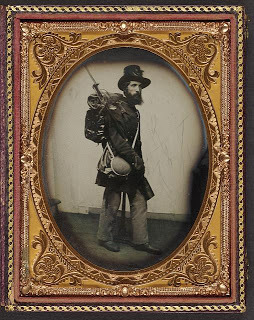

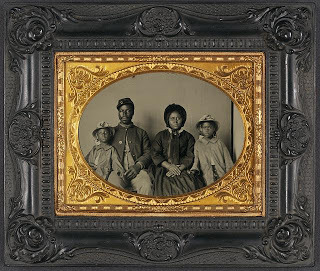

Dead Americans618,000 Americans died in the Civil War war, 68,000 of them African-American. That was the cost of that war. Though few understood it at the time, those 618,000 husbands, sons, and brothers were consumed by an epic battle of industrialization wrestling agriculture for the reins of the North American continent. Which is not to say the Civil War was not about slavery—it was. But it was also about the deal that had been brokered by the Constitution that had been unraveling for decades. It was about changing technologies and energy sources, and how society necessarily had to evolve as a result. It was about immigration and conflicting, competing economic models. And, like most wars, underneath it all it was about money and power and who would possess them.  Soldier and familyIn the end, the South chose to dig in its heels rather than adapt to the moral, economic and technological pressures demanding it change. In the end, the North couldn't allow a powerful, hostile country to stretch all the way across its southern border. If they didn't fight the Confederacy after Fort Sumter, they would've inevitably fought them a few years later over control of the western territories. For its security and future wealth, the North had to both defeat and crush the South to remove it as a threat. That this would impoverish and embitter a future third of the country for the next century was either not taken into account or considered an adequate price to pay.

Soldier and familyIn the end, the South chose to dig in its heels rather than adapt to the moral, economic and technological pressures demanding it change. In the end, the North couldn't allow a powerful, hostile country to stretch all the way across its southern border. If they didn't fight the Confederacy after Fort Sumter, they would've inevitably fought them a few years later over control of the western territories. For its security and future wealth, the North had to both defeat and crush the South to remove it as a threat. That this would impoverish and embitter a future third of the country for the next century was either not taken into account or considered an adequate price to pay.The Civil War is valuable to remember as an example of what happens when patched-together compromises can no longer hold. It's what happens when adaptive small changes—often known as reforms—are resisted, forcing large changes—often known as revolutions or collapse—to come all at once. It's what happens when, in the face of historic forces, a people says its way of life is non-negotiable and then finds out that, indeed, history does not negotiate.

There is value in remembering people and events in all their complexity--their good and their bad, their dark and their light. We gain when we comprehend the entirety of a person or an era (or as close as we can get to it) rather than a sanitized, one-sided version. The Civil War, with its suffering, loss, and heartache, should make us sad and even uncomfortable. And it's important to acknowledge that our leaders, even the ones we most admire, had failings as well as strengths. This approach doesn't make for a good party. There's no basking in any nostalgic, rosy glow. But an honest look back lets us embrace both the wonder and the warts of our history and let us know ourselves—our own virtues and our own failings--better because of it. In this way the mystic chords of our nation's memory, dissonant though they may still be, can slowly grow in harmony.

Published on May 23, 2011 21:26

Pearl City Control Theory, a Novel Available as Ebook $2.99

Pearl City Control Theory, a novel of city Buddha-mind walking, love and breaking free is available as an ebook on both Nook and Kindle for just $2.99.

Pearl City Control Theory, a novel of city Buddha-mind walking, love and breaking free is available as an ebook on both Nook and Kindle for just $2.99. It's a modern comedy of manners set in urban San Francisco, very different than Beaufort 1849! Here's the description:

When Sara's husband, Mark, goes to the East Coast for law school, Sara stays behind in her beloved San Francisco. Their marriage will be BCDR -- bi-coastal, dual rental. It's only for three years, Sara tells herself. An admirer of efficiency, she intends to keep loneliness at bay by moving in with her erratic sister, Amanda, and by staying busy at work in her newly promoted position as a manager for a large consumer products manufacturer.

But Sara's tightly controlled world starts to crack when she accepts the help of an inscrutable mentor and begins volunteering at a domestic violence shelter on the weekends. As mercurial Amanda does her best to disarray the order of Sara's life, challenges at work and at the shelter test Sara's resolve and illuminate the fissures in her careful structures. To top it off, Sara finds her mentor far too helpful when she knows she shouldn't be seeing him at all . . .

Published on May 23, 2011 15:38

May 17, 2011

Win a free copy of Beaufort 1849!

I am guest blogging for the next couple days at author Suzanne Adair's blog.

Suzanne Adair's Blog--The Improbable Story of Robert Smalls

Leave a comment on this post at her blog for a chance to win a free copy of Beaufort 1849!

Suzanne Adair's Blog--The Improbable Story of Robert Smalls

Leave a comment on this post at her blog for a chance to win a free copy of Beaufort 1849!

Published on May 17, 2011 07:52

May 13, 2011

Between the Wars

Roaring through the twentiesI've been on a jag lately of immersing myself in the culture of upper-crust Britain in the decades between the world wars. Though I've long been a fan of P.G. Wodehouse and Mrs. Dalloway, now, from re-watching Granada Television's Brideshead Revisted (oh so good), to reading Nancy Mitford's Love in a Cold Climate, to tearing through a number of lightweight Georgette Heyer period mysteries, the twilight of the British aristocracy has been on my mind. Ah, the details that no other era can match! Mannish women wearing monocles, the plover eggs at an Oxford luncheon, snobby countesses in tiaras, bathtubs full of newts. Who can forget Poirot in his white spats, or Bertie chasing his cow creamer while his faithful Jeeves rescues him from a dreaded Aunt or two? In this manic world, Cedric and Lady Montford prance together in their jewels, Sebastian laments about the bad mood of his teddy bear Aloysius, and the butler never does it but gets killed instead.

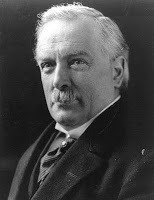

Roaring through the twentiesI've been on a jag lately of immersing myself in the culture of upper-crust Britain in the decades between the world wars. Though I've long been a fan of P.G. Wodehouse and Mrs. Dalloway, now, from re-watching Granada Television's Brideshead Revisted (oh so good), to reading Nancy Mitford's Love in a Cold Climate, to tearing through a number of lightweight Georgette Heyer period mysteries, the twilight of the British aristocracy has been on my mind. Ah, the details that no other era can match! Mannish women wearing monocles, the plover eggs at an Oxford luncheon, snobby countesses in tiaras, bathtubs full of newts. Who can forget Poirot in his white spats, or Bertie chasing his cow creamer while his faithful Jeeves rescues him from a dreaded Aunt or two? In this manic world, Cedric and Lady Montford prance together in their jewels, Sebastian laments about the bad mood of his teddy bear Aloysius, and the butler never does it but gets killed instead. Lloyd George--no fan of lordsIt's an odd literary flowering that documents this period of frantic parties and still opulent displays of wealth. The first World War, the great one, had finished this particular group of people off, even if they hadn't realized it quite yet. But the changes had been raining down for a while, working to erode centuries of privilege stretching from the Middle Ages. One could say it began with the repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1846 that allowed cheap grain to be imported into Britain from other countries, lowering domestic agricultural profits. Others might say it was the invention of the spinning jenny and the cotton gin that created a capitalist-mercantile class, a class that spent most of the nineteenth century fighting to expand its wealth and influence at the expense of its more refined brethren. The aristocracy, however, not without a trick or two themselves, fought back and hung on. As late as 1880, these seven thousand families owned four-fifths of the land in Britain. They dominated government and social prestige, controlled the Houses of Parliament, and filled the ranks of the army, church and civil service with their second and third sons. In 1884 another blow was struck with a series of reform measures that allowed nearly 60% of the male population to vote. (Gosh, sounds radical.) And then in 1913 Lloyd George, a Welshman no fan of landlords, pushed through his "Land Campaign" with higher taxes for landowners, government control of rents, and higher wages for laborers. The coffin for the aristocracy had been built and the grave dug, but the body was still kicking. Then came the war.

Lloyd George--no fan of lordsIt's an odd literary flowering that documents this period of frantic parties and still opulent displays of wealth. The first World War, the great one, had finished this particular group of people off, even if they hadn't realized it quite yet. But the changes had been raining down for a while, working to erode centuries of privilege stretching from the Middle Ages. One could say it began with the repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1846 that allowed cheap grain to be imported into Britain from other countries, lowering domestic agricultural profits. Others might say it was the invention of the spinning jenny and the cotton gin that created a capitalist-mercantile class, a class that spent most of the nineteenth century fighting to expand its wealth and influence at the expense of its more refined brethren. The aristocracy, however, not without a trick or two themselves, fought back and hung on. As late as 1880, these seven thousand families owned four-fifths of the land in Britain. They dominated government and social prestige, controlled the Houses of Parliament, and filled the ranks of the army, church and civil service with their second and third sons. In 1884 another blow was struck with a series of reform measures that allowed nearly 60% of the male population to vote. (Gosh, sounds radical.) And then in 1913 Lloyd George, a Welshman no fan of landlords, pushed through his "Land Campaign" with higher taxes for landowners, government control of rents, and higher wages for laborers. The coffin for the aristocracy had been built and the grave dug, but the body was still kicking. Then came the war. The dead left behind in FranceThe young men of this class and era, schooled at Eton and Harrow and Cambridge and Oxford, had been groomed to lead and rule, so when war with the Kaiser came, they promptly volunteered to command troops for king and country. But it turned out to be a different kind of war than anyone expected, and in France and Flanders men died or were maimed in horrific numbers. It was a bloodletting that diminished all of Britain but impacted aristocratic young men in disproportionate numbers.

The dead left behind in FranceThe young men of this class and era, schooled at Eton and Harrow and Cambridge and Oxford, had been groomed to lead and rule, so when war with the Kaiser came, they promptly volunteered to command troops for king and country. But it turned out to be a different kind of war than anyone expected, and in France and Flanders men died or were maimed in horrific numbers. It was a bloodletting that diminished all of Britain but impacted aristocratic young men in disproportionate numbers.

Party time

Party timeThe war also brought an abrupt end to many repressive Victorian mores, and when the armistice finally arrived, the freedom was exhilarating. Still, even in the midst of parties and gaiety and cocktails and flappers, the landed gentry sensed something was wrong. Already financial troubles were knocking at the door even if they did their best not to listen. Already the older generation raged at the assaults on their wealth and prerogatives, or worse, resigned to their fate, sold off millions of acres of inherited land--one of the largest transfers of territory in British history--just to stay afloat. Country houses and London town homes soon followed until the landed class had no land to pass onto their children. With the corpse in the coffin, the twenties and thirties were a glorious two-decade wake.

The final, most undignified blow followed the second war. After a hefty increase in taxes to pay for debt brought on by the war, and a hefty increase in wages for the average worker, no one could afford servants at all. Without chambermaids, valets, gardeners and cooks, estates couldn't be maintained, dinner parties couldn't be given, and being an Earl or Duchess grew suddenly irrelevant. It took Hitler and WWII to hammer down the final nails in the British aristocratic coffin, and then that class was buried into obscurity and irrelevance for good.

Though there is art and architecture from these decades that evokes the style and exuberance and wild social change of the era, I think it is literature that captures it best. This is true even if the novel or story was written slightly later and tinted by nostalgia for something that can be revisited in memory but never regained. Was this lost world a paradise? Well, it was certainly nice for those seven thousand families. Should its passing be mourned? A harder question to answer. Yes, something has been lost, and the world is still missing it. But dead bodies have to be buried. No one wants to live with zombies in tiaras and spats.

Though there is art and architecture from these decades that evokes the style and exuberance and wild social change of the era, I think it is literature that captures it best. This is true even if the novel or story was written slightly later and tinted by nostalgia for something that can be revisited in memory but never regained. Was this lost world a paradise? Well, it was certainly nice for those seven thousand families. Should its passing be mourned? A harder question to answer. Yes, something has been lost, and the world is still missing it. But dead bodies have to be buried. No one wants to live with zombies in tiaras and spats.

Published on May 13, 2011 19:05

May 6, 2011

The Aiken-Rhett House: Take a Ride on the Roller Coaster of History

I like grand old houses, their craftsmanship, their whimsy, their attention to detail. A fine house can charm the senses and even, on occasion, uplift the soul. But best of all is when a house has a story to tell.

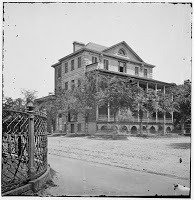

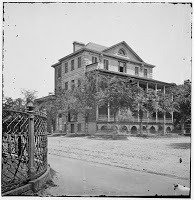

Aiken-Rhett house in 1865 Often a century or two of renovations muddy the narrative or even lose the storyline altogether in favor of central air and indoor plumbing--modern conveniences that are understandable enough, I admit. However, to my delight, in Charleston, South Carolina, there exists a house where the whispers of history are abundant, where layers of generation upon generation are still plainly in view. It is a house that depicts the rise and fall not only of a family but of an entire civilization. It is the Aiken-Rhett house.

Aiken-Rhett house in 1865 Often a century or two of renovations muddy the narrative or even lose the storyline altogether in favor of central air and indoor plumbing--modern conveniences that are understandable enough, I admit. However, to my delight, in Charleston, South Carolina, there exists a house where the whispers of history are abundant, where layers of generation upon generation are still plainly in view. It is a house that depicts the rise and fall not only of a family but of an entire civilization. It is the Aiken-Rhett house.

The house was built by Charleston merchant John Robinson who, with the fickleness of early nineteenth century fortunes, lost it soon afterwards. It was then bought by William Aiken, Sr., a prosperous Irish merchant, to be used as rental property. (Pretty grand rental property, even back then!) When Aiken Sr. died in a carriage accident (notice a theme of reversals?) the house was left to his son, William Aiken, Jr. He promptly moved in with his bride, Harriet Lowndes, the beautiful and well-educated daughter of a South Carolina political grandee. She spoke four languages and was destined to become one of Charleston's leading hostesses. This son of an immigrant had truly made his way into Charleston society.

Grand EntrywayTime for renovations! The house was expanded and upgraded into one of the most magnificent residences in Charleston, a city not lacking in resplendent abodes. Aiken himself became a big cheese not only in Charleston, but the entire state, elected both governor of South Carolina in 1844 and a member of Congress in 1851. Owner of a number of plantations, he was also one of the largest slaveholders in the state.

Grand EntrywayTime for renovations! The house was expanded and upgraded into one of the most magnificent residences in Charleston, a city not lacking in resplendent abodes. Aiken himself became a big cheese not only in Charleston, but the entire state, elected both governor of South Carolina in 1844 and a member of Congress in 1851. Owner of a number of plantations, he was also one of the largest slaveholders in the state.

Slave quarters and other outbuildings At the back of the Charleston house were outbuildings where the ten to twenty house slaves that worked there during the antebellum years could often be found—in the kitchen, laundry, stables, carriage house, and in their living quarters in the upper parts of these buildings.

Slave quarters and other outbuildings At the back of the Charleston house were outbuildings where the ten to twenty house slaves that worked there during the antebellum years could often be found—in the kitchen, laundry, stables, carriage house, and in their living quarters in the upper parts of these buildings.

In the 1850's the price of cotton went sky-high. Time for more renovations! The interior was redecorated and an art gallery was constructed for the collection of paintings and sculptures that the Aiken's brought back from their extensive tour of Europe.