Terri Windling's Blog, page 164

May 5, 2014

A life-enhancing art, and an art-enhancing life

From May Sarton's reminiscence of Virginia Woolf (published in Sarton's Journal of Solitude):

"The sheer vital energy of the Woolfs always astonishes me when I stop to consider what they accomplished on any given day. Fragile she may have been, living on the edge of psychic disturbance, but think what she managed to do nonetheless -- not only the novels (every one a breakthrough in form), but all those essays and reviews, all the work of the Hogarth Press, not only reading mss. and editing, but, at least at the start, packing the books to go out!

"And besides all that, they lived such an intense social life. (When I went there for tea, they were always going out for dinner and often to a party later on.) The gaiety and the fun of it all, the huge sense of life! The long, long walks through London that Elizabeth Bowen told me about. And two houses to keep going! Who of us could accomplish what she did?

"There may be a lot of self-involvement in A Writer's Diary, but there is no self-pity (and what has to be remembered is that what Leonard published at that time was only a small part of all the journals, the part that concerned her work, so it had to be self-involved). It is painful that such genius should evoke such mean-spirited response at present. Is genius so common that we can afford to brush it aside? What does it matter if she is major or minor, whether she imitated Joyce (I believe she did not), whether her genius was a limited one, limited by class? What remains true is that one cannot pick up a single one of her books and read a page without feeling more alive. If art is not to be life-enhancing, what is it to be?"

A good question indeed.

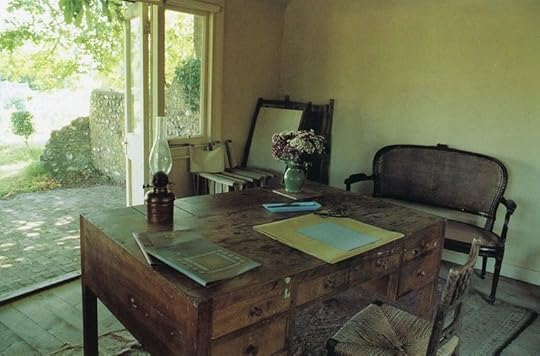

The pictures above are of Monks House, Virginia and Leonard Woolf's country house in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex. This 17th century house -- decorated with painted furniture, fabrics, and art by Virginia's artist sister Vanessa Bell (who lived nearby at Charleston) and other artist friends -- is now a National Trust property.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Songs for spring and the month of May:

Above, "Mummer's Dance" by singer/songwriter and Celtic music scholar Loreena McKennitt, from Canada.

Below, an instrumental piece: "May Morning Dew," performed by the Irish band Moving Hearts (during their 2007 reunion).

Next:

Singer/songwriter Kate Rusby, from Yorkshire, and Irish fiddler Kevin Burke join with the Irish band Dervish to perform "As I Roved Out."

And last:

Back to Loreena McKennitt, performing "Beltane Fire Dance" in Spain.

May 1, 2014

Sun stories

by Mary Oliver

Come with me

into the field of sunflowers.

Their faces are burnished disks,

their dry spines

creak like ship masts,

their green leaves,

so heavy and many,

fill all day with the sticky

sugars of the sun.

Come with me

to visit the sunflowers,

to visit the sunflowers,

they are shy

but want to be friends;

they have wonderful stories

of when they were young -

the important weather,

the wandering crows.

Don't be afraid

to ask them questions!

Their bright faces,

which follow the sun,

will listen, and all

those rows of seeds -

each one a new life!

hope for a deeper acquaintance;

each of them, though it stands

in a crowd of many,

in a crowd of many,

like a separate universe,

is lonely, the long work

of turning their lives

into a celebration

is not easy. Come

and let us talk with those modest faces,

the simple garments of leaves,

the coarse roots in the earth

so uprightly burning.

Oh how I love this line from the poem: the long work of turning their lives into a celebration is not easy. Because easy or not, that's precisely the "long work" I want to do too, in both life and art.

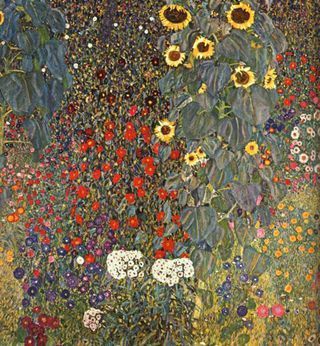

The art above is "Vase With Fifteen Sunflowers" by the French Symbolist painter Odilon Redon (1840-1916); "Farm Garden With Sunflowers" and "Sunflowers" by the Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918); "The Lesson, with Sunflowers" by the Swedish Arts & Crafts painter/designer Carl Larsson (1853-1919); "Clytie," a water nymph turned into a sunflower in Greek mythology, by the German Symbolist painter Louis Welden Hawkins (1849-1910); and "Two Cut Sunflowers" by the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). Below is "Sunflower," a 19th century wallpaper design created by Bruce James Talbert for Jeffrey & Co. London (1878), and a sunflower child from one of my old sketchbooks.

The poem above comes from Dream Work by Mary Oliver (Atlantic Monthly Press); all rights reserved by the author.

April 30, 2014

Moon stories (for Beltane)

And they will gather by the well,

its dark water a mirror to catch whatever

stars slide by in the slow precession of

the skies, the tilting dome of time,

over all, a light mist like a scrim,

and here and there some clouds

that will open at the last and let

the moon shine through; it will be

at the wheel’s turning, when

three zeros stand like paw-prints

in the snow; it will be a crescent

moon, and it will shine up from

the dark water like a silver hook

without a fish -- until, as we lean closer,

swimming up from the well, something

dark but glowing, animate, like live coals --

it is our own eyes staring up at us,

as the moon sets its hook;

and they, whose dim shapes are no more

than what we will become, take up

their long-handled dippers

of brass, and one by one, they catch

the moon in the cup-shaped bowls,

the moon in the cup-shaped bowls,

and they raise its floating light

to their lips, and with it, they drink back

our eyes, burning with desire to see

into the gullet of night: each one

dips and drinks, and dips, and drinks,

until there is only dark water,

until there is only the dark.

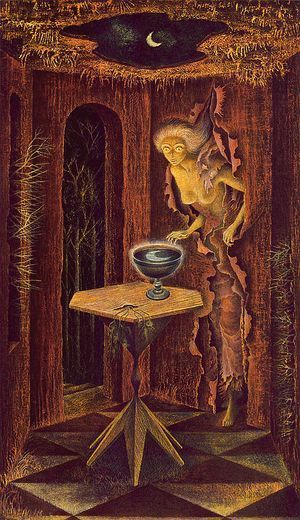

The paintings here are by the great Surrealist painter Remedios Varo (1908-1963), who was born in Girona, Spain, studied art in Madrid, fled to Paris during the Spanish Civil War and to Mexico when the Germans occupied France. She then spent the rest of her life in Mexico, where she worked closely with the English Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. For more information on this wonderful artist, I recommend Janet A. Kaplan's fine biography, Unexpected Journeys; and Surreal Friends, by Joanna Moorhead & Sefan van Raay, about the friendship between Varo, Carrington, and photographer Kati Horna. (Varo, by the way, was a formative influence on the character of Anna Navarro in my novel The Wood Wife.)

The poem above is from The Girl With Bees in Her Hair by Eleanor Wilner (Copper Canyon Press); it appeared online on poets.org. All rights are reserved by the author.

April 29, 2014

Transmigration stories

Some stories last many centuries,

others only a moment.

All alter over that lifetime like beach-glass,

grow distant and more beautiful with salt.

Yet even today, to look at a tree

Yet even today, to look at a tree

and ask the story Who are you? is to be transformed.

There is a stage in us where each being, each thing, is a mirror.

Then the bees of self pour from the hive-door,

ravenous to enter the sweetness of flowering nettles and thistle.

Next comes the ringing a stone or violin or empty bucket

gives off --

the immeasurable's continuous singing,

before it goes back into story and feeling.

In Borneo, there are palm trees that walk on their high roots.

Slowly, with effort, they lift one leg then another.

I would like to join that stilted transmigration,

I would like to join that stilted transmigration,

to feel my own skin vertical as theirs:

an ant-road, a highway for beetles.

I would like not minding, whatever travels my heart.

To follow it all the way into leaf-form, bark-furl, root-touch,

and then keep walking, unimaginably further.

The ephemeral "land art" here is by the British sculptor, photographer, and installation artist Andy Goldsworthy, whose influential work has been documented in Wood, Stone, Time, Arch, Passage, Hand to Earth, and other gorgeous art books. Goldsworthy was born in Cheshire, grew up in Leeds, studied fine art in Lancashire, and now lives and works in Scotland. You'll find his reflections on his work in the hidden picture captions. (Run your cursor over the photographs to see them.)

The poem above comes from Given Sugar, Given Salt by Jane Hirshfield (Harper Perrenial), and appeared online in Poetry Chaikhana; all right reserved by the author.

The poem above comes from Given Sugar, Given Salt by Jane Hirshfield (Harper Perrenial), and appeared online in Poetry Chaikhana; all right reserved by the author.

April 28, 2014

Creation stories

Working Together

by David Whyte

We shape our self

to fit this world

and by the world

are shaped again.

The visible

and the invisible

working together

in common cause,

to produce

the miraculous.

I am thinking of the way

the intangible air

passed at speed

round a shaped wing

easily

holds our weight. So may we, in this life

So may we, in this life

trust

to those elements

we have yet to see

or imagine,

and look for the true

shape of our own self,

by forming it well

to the great

intangibles about us.

The drawings and paintings here are from the Days of Creation series by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1899). The five surviving paintings are now in the collection of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts...where I loved to go visit them, back in my Boston days. These designs were also turned into stained glass windows by Burne-Jones and William Morris, for their Arts & Crafts company Morris & Co (which is still in operation). The window below (Day 4) is installed in the Chapel of Manchester College, Oxford.

"For every locomotive they build, I shall paint another angel.” - Sir Edward Burne-Jones

"Working Together" was first published in The House of Belonging by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press) and appears online on Whyte's website. All rights reserved by the author.

"Working Together" was first published in The House of Belonging by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press) and appears online on Whyte's website. All rights reserved by the author.

April 27, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

To start off today, we're heading back to medieval France and Germany....

Above: "The Mass of Notre Dame," a thoroughly goregous polyphonic mass by the 14th century French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut. This is the full order of the mass, with multi-part Gegorian settings for the proprium parts, sung by the French Ensemble Gilles Binchois, under the direction of Dominique Vellard.

Below, an improvisation on an extract from "Spiritus Sanctus" by the great 12th century German abbess and mystic Hildegard of Bingen.The piece is performed by Geraldine Zeller (soprano) and Helge Burggrabe (bass recorder), recorded in a dress rehearsal for a concert at Heppenheim Cathedral in Hesse, Germany (2010).

Next, a very beautiful contemporary piece that was inspired by Hildegard von Bingen and her music:

"Vespers for St. Hildegard," composed and directed by Stevie Wishart, performed at York Minster (Cathedral) in the north of England by Wishart's terrific Early Music group, Sinfonye, accompanied by the University of York Chamber Choir. (Wishart is the woman with the hurdy-gurdy, next to the harpist.) The piece was commisioned for the 2013 York Early Music Festival.

We're firmly back in the 21st century with the ending piece: my absolute favorite Stevie Wishart composition, "Heed My Spreading Wings," performed by one of my favorite new musical groups, called Voice.

Voice is a London-based acapella trio (Victoria Couper, Clemmie Franks, and Emily Burn) with a repetoire ranging from medieval to modern, drawn from traditions around the globe. In the video below, they sing "Heed My Spreading Wings" at Hugh Church in Faringdon, Oxfordshire (2012). The piece was commissioned by Voice for the New Music programme, Megaphones for the Unheard. This one could be my anthem....

Today's music is for my dear friend Midori Snyder.

April 24, 2014

What makes a good writing day?

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

"A good day? I get up, I wake my teenage son up, we have breakfast, and he leaves at 8. That’s the cue for me to go to my office. My writing life has shifted slightly over the years, but what works best for me now is if I start writing immediately. I’ll check my email to make sure there’s nothing I need to deal with right away, then I read what I’ve written the day before. That jolts me into continuing. Ideally, the day before I’ve left a little bit left in the tank, so to speak. Not like Graham Greene — he used to write 500 words a day, and if the 500th word was in the middle of a sentence, he’d stop. I’m not that bad, but what’s really useful is to have a little left that you haven’t quite gotten down on paper. Then I can use that in the morning to get started. A lot of times, if the writing goes well, I’ll be done by 10. Sometimes I’m still working at 6. It depends on what I come up against."

"I get up around 4:30 or 5 at the latest. I usually go until I get tired, until about 9 or 10. Then I quit and monkey around. That monkeying around could be anything: research, working out, paying bills, flossing my teeth…I have a whole array of delaying behaviors that usually don’t kick in until 9 or 10. At 5 in the morning I’m too sleepy to do anything but try to think about what I was last working on. My mind is clearer. Through the day sometimes I’ll practice music. I push through the day, get my son to school. Then after dinner, 7 or 8, I’ll have a go at writing again, if I’m really deep into it.

"I can write anywhere. I was on the train this morning writing. I usually write the first few pages longhand. I used to write a lot longhand. I still write my first 20-30 pages longhand. Then I move to the computer, or I’ll type it — I still use a typewriter, too. I used to use a typewriter a lot more. I needed it early in my career. The computer makes you rewrite and just hit the 'insert' key. The insert key is deadly for a writer. You really have to push forward, know you’re going to discard and rewrite everything. Man, I rewrite everything. Even emails I rewrite."

Above: Hawker's Hut, built by poet Rpbert Stephen Hawker (1803-1875) near Morwenstow, Cornwall.

Below, a writer's hut built by poet Robert Duncan (1919-1988), also near Morwenstow.

"A day like today started around 4 in the morning, because often my kids wake me by yowling in their sleep. Then I’m bolt upright, wide awake, so I figure I might as well use that time in the middle of the night, so I hop up and do a bit of work. More typically I would get the kids off to school around 8:30, then I rush to my computer. I wish that what followed was actual writing. That would be bliss. But I admit that I first make my way through a fast-growing undergrowth of business....

"I know you’re supposed to do the writing first and leave the administrative stuff for later in the day, but I can’t see my way clear to do the writing until I’ve answered those wretched new emails. When I think back to when I had infinite time to write, before we had kids, I don’t think I did my best writing first thing in the morning. I need to warm up. Maybe in fact, by devoting the first hour of the day to silly business, I’m saving the better creative time for later. But sometimes the 'business' takes all day; I look up and it’s already 4, and I have to rush off to the bus stop to pick up the children."

"I don’t like getting up early, but I do because of school — driving my daughter to school is a good thing about my day. When I get back, either I walk/run our dog or go straight upstairs and sit down in the same chair I’ve had since 1981 — just the right arm height for a board to lay across and then I can sit there and write. A friend upholsters this chair every fifth year, and it is currently covered in red mohair velvet. My cousin’s quilt drapes the back of the chair. I am sort of obsessive about having things around me from my family — these objects pop up in the books."

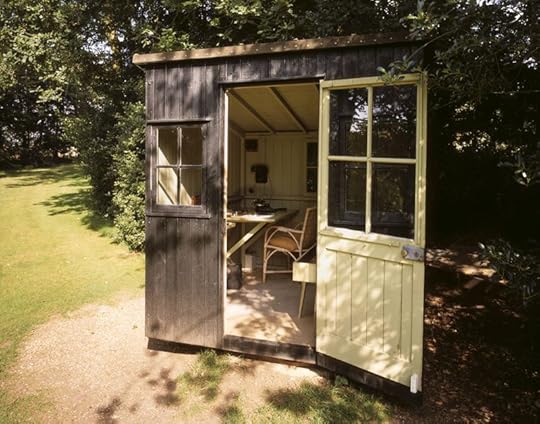

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire. (It rotated to catch the best sunlight.)

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire. (It rotated to catch the best sunlight.)

"The only time I have for writing is when I’m back home in England, in the house I grew up in, where all my things are, my books. Many times, I’ve got to try to get a lot of writing done in just, maybe, five days. That means setting the alarm for five o’clock. Desperately writing until breakfast, going back to write again. Always taking an hour off to spend with the dog. And in the evening I spend time with my sister — we own the house together and she lives in it with her family. Then I sometimes have to go back and write late into the night. It’s a very stressful way to write, high and edgy."

"Flora and I have four young children, so I write late into the night — the only time our home is silent. At three in the morning, I usually collapse on the narrow bed in my study, but am often woken a couple of hours later by one or both of our 3-year-old twins, who like to waddle down from their room and climb on top of me. At 8, I make pancakes for the children, then sleep again until 11. This is when the day really begins. I make myself a cup of tea, sit at my desk, phone my friends in Beijing, read for a while, then start thinking about what I am going to write."

"I can’t write every day. I’m a binger. I like to go six or seven hours at a time, without a break, then go off somewhere and drink something."

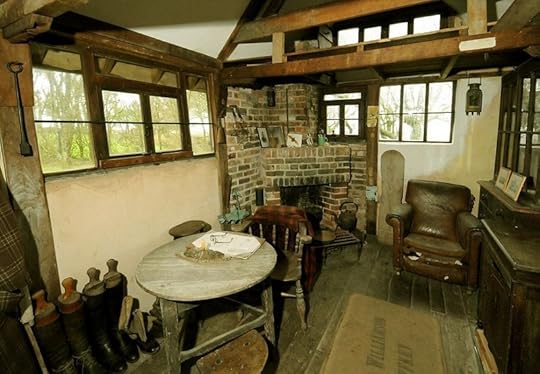

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

"I’d be lucky to have a morning routine! But let’s pretend…. I’d get up in the morning, have breakfast, have coffee, then go upstairs to the room where I write. I’d sit down and probably start transcribing from what I’d [hand]written the day before.... I don’t think there’s anything too unusual about [my study], except that it’s full of books and has two desks. On one desk there’s a computer that is not connected to the internet. On the other desk is a computer that is connected to the internet. You can see the point of that!"

"When I’m rewriting, and it’s progressing, I begin breathing audibly through my nose. I like to proofread in noisy restaurants, with my glasses off, staring close at the type. I love the feeling of sealing up a FedEx envelope — that soft, cool fibrous Tyvek bending around the corner of a block of page proofs — and sending it off. Lately, working on Traveling Sprinkler, I’ve been writing in the car, so what I see is whatever is out the windshield — usually leaves, other cars, fireflies. The dashboard is the desk, complete with coffee stains."

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

"I find that writing a first draft is very difficult and laborious. It is also often quite disappointing. It hardly ever turns out to be what I thought it was, and it usually falls quite short of the ideal I held in my mind when I began writing it. I love to rewrite, however. A first draft is really just a sketch on which I add layer and dimension and shade and nuance and color. Writing for me is largely about rewriting. It is during this process that I discover hidden meanings, connections, and possibilities that I missed the first time around. In rewriting, I hope to see the story getting closer to what my original hopes for it were.

"I write while my kids are at school and the house is quiet. I sequester myself in my office with mug of coffee and computer. I can't listen to music when I write, though I have tried. I pace a lot. Keep the shades drawn. I take brief breaks from writing, 2-3 minutes, by strumming badly on a guitar. I try to get 2–3 pages in per day. I write until about 2 p.m. when I go to get my kids, then I switch to Dad mode."

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

"I try to write 1000 words on a good day, about three pages. The reason for that amount, it feels right to me because most of the scenes I write are 3000-4000 words long. Not always, but on average. That means that I get 3-4 days per scene, which is good, because sometimes I’ll read it and feel — I feel different on different days, so it means I won’t have just one tone per scene. I have several different cracks at it.

"I’ll often be in the middle of writing and realize I don’t know what I’m writing about. For instance, today I’ve been writing a scene about a man who’s grafting apple trees. So I have to stop and look at my notes about grafting. Just now I was thinking, I still don’t really understand this. I need to order a book at the British Library and go and read it tomorrow. That’s what happens as I go. So what I’ll do is write a basic part of the scene, but for the grafting bit…I’ll put down three stars. Three stars in a manuscript for me means there’s something missing, I have to go back and fill it out. I don’t want it to stop my writing flow, but I’ll leave it aside and do the rest of the scene without it, come back and fill it in later. That’s a good interruption. A bad interruption is when I can’t focus and I wind up fiddling around online, having lunch with a friend, or something like that. What I’m aiming for is that concentrated time of focusing."

The writing hut in North Devon where naturalist Henry William Williamson

wrote Tarka the Otter.

The writing hut in North Devon where naturalist Henry William Williamson

wrote Tarka the Otter.

"I know many writers who try to hit a set word count every day," Russell continues, "but for me, time spent inside a fictional world tends to be a better measure of a productive writing day. I think I’m fairly generative as a writer, I can produce a lot of words, but volume is not the best metric for me. It’s more a question of, did I write for four or five hours of focused time, when I did not leave my desk, didn’t find some distraction to take me out of the world of the story? Was I able to stay put and commit to putting words down on the page, without deciding mid-sentence that it’s more important to check my email, or 'research' some question online, or clean out the science fair projects in the back for my freezer?

"For me, a good writing day is when I can move forward inside a story, because I take so much pleasure in tinkering with sentences that I often have to fight my own impulse to dither and revise in order to keep the momentum of the narrative going. So if I can move in a linear way through the story, and stay zipped inside the story, not jinx myself with despair or frustration or over-confidence or self-consciousness, and be basically okay with not-knowing what is going to happen from one sentence to the next, that’s a great writing day. Writers are such excellent self-saboteurs, though. I swear, I can hijack my own writing day in a hundred ways — I can eject myself from a story because I’ve decided it’s 'going good.' There’s this excruciating aspect of joy, I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced this, where you almost want to interrupt it. For me, the experience of losing myself in a character can feel intolerably wonderful. So I’ve decided that the trick is just to keep after it for several hours, regardless of your own vacillating assessment of how the writing is going....

"Showing up and staying present is a good writing day."

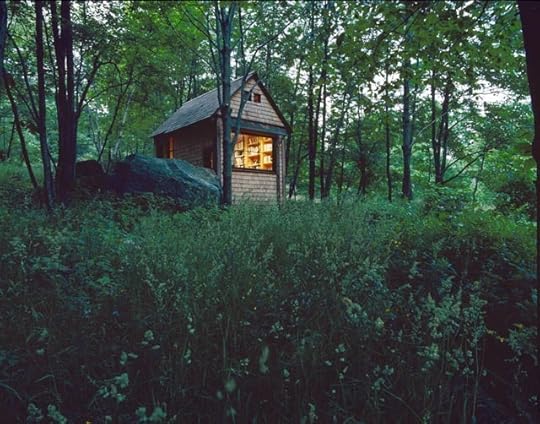

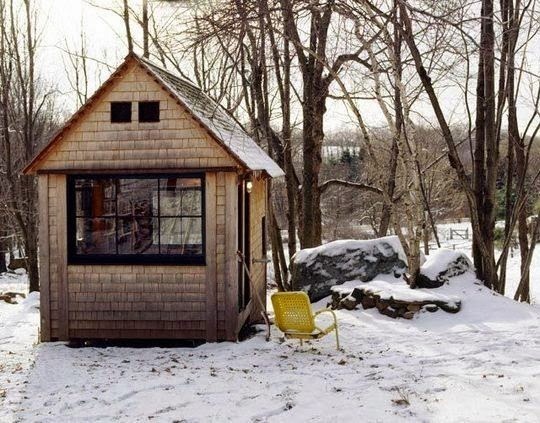

Michael Pollan's wrote a book about building this writing hut: A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams.

Michael Pollan's wrote a book about building this writing hut: A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams.

"On a shelf above my computer are five letters that spell out W-R-I-T-E. Just in case I forget why I’m there."

The writing day

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

"A good day? I get up, I wake my teenage son up, we have breakfast, and he leaves at 8. That’s the cue for me to go to my office. My writing life has shifted slightly over the years, but what works best for me now is if I start writing immediately. I’ll check my email to make sure there’s nothing I need to deal with right away, then I read what I’ve written the day before. That jolts me into continuing. Ideally, the day before I’ve left a little bit left in the tank, so to speak. Not like Graham Greene—he used to write 500 words a day, and if the 500th word was in the middle of a sentence, he’d stop. I’m not that bad, but what’s really useful is to have a little left that you haven’t quite gotten down on paper. Then I can use that in the morning to get started. A lot of times, if the writing goes well, I’ll be done by 10. Sometimes I’m still working at 6. It depends on what I come up against."

"I get up around 4:30 or 5 at the latest. I usually go until I get tired, until about 9 or 10. Then I quit and monkey around. That monkeying around could be anything: research, working out, paying bills, flossing my teeth … I have a whole array of delaying behaviors that usually don’t kick in until 9 or 10. At 5 in the morning I’m too sleepy to do anything but try to think about what I was last working on. My mind is clearer. Through the day sometimes I’ll practice music. I push through the day, get my son to school. Then after dinner, 7 or 8, I’ll have a go at writing again, if I’m really deep into it. I can write anywhere. I was on the train this morning writing. I usually write the first few pages longhand. I used to write a lot longhand. I still write my first 20-30 pages longhand. Then I move to the computer, or I’ll type it — I still use a typewriter, too. I used to use a typewriter a lot more. I needed it early in my career. The computer makes you rewrite and just hit the 'insert' key. The insert key is deadly for a writer. You really have to push forward, know you’re going to discard and rewrite everything. Man, I rewrite everything. Even emails I rewrite."

Hawker's Hut, built by the Victorian poet Stephen Hunter Hawker on a cliffside near Morwenstow, Cornwall

Hawker's Hut, built by the Victorian poet Stephen Hunter Hawker on a cliffside near Morwenstow, Cornwall

"The only time I have for writing is when I’m back home in England, in the house I grew up in, where all my things are, my books. Many times, I’ve got to try to get a lot of writing done in just, maybe, five days. That means setting the alarm for five o’clock. Desperately writing until breakfast, going back to write again. Always taking an hour off to spend with the dog. And in the evening I spend time with my sister — we own the house together and she lives in it with her family. Then I sometimes have to go back and write late into the night. It’s a very stressful way to write, high and edgy."

"Flora and I have four young children, so I write late into the night—the only time our home is silent. At three in the morning, I usually collapse on the narrow bed in my study, but am often woken a couple of hours later by one or both of our 3-year-old twins, who like to waddle down from their room and climb on top of me. At 8, I make pancakes for the children, then sleep again until 11. This is when the day really begins. I make myself a cup of tea, sit at my desk, phone my friends in Beijing, read for a while, then start thinking about what I am going to write."

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire

"A day like today started around 4 in the morning, because often my kids wake me by yowling in their sleep. Then I’m bolt upright, wide awake, so I figure I might as well use that time in the middle of the night, so I hop up and do a bit of work. More typically I would get the kids off to school around 8:30, then I rush to my computer. I wish that what followed was actual writing. That would be bliss. But I admit that I first make my way through a fast-growing undergrowth of business.... I know you’re supposed to do the writing first and leave the administrative stuff for later in the day, but I can’t see my way clear to do the writing until I’ve answered those wretched new emails. When I think back to when I had infinite time to write, before we had kids, I don’t think I did my best writing first thing in the morning. I need to warm up. Maybe in fact, by devoting the first hour of the day to silly business, I’m saving the better creative time for later. But sometimes the business" takes all day, I look up and it’s already 4, and I have to rush off to the bus stop to pick up the children."

"I don’t like getting up early, but I do because of school — driving my daughter to school is a good thing about my day. When I get back, either I walk/run our dog or go straight upstairs and sit down in the same chair I’ve had since 1981—just the right arm height for a board to lay across and then I can sit there and write. A friend upholsters this chair every fifth year, and it is currently covered in red mohair velvet. My cousin’s quilt drapes the back of the chair. I am sort of obsessive about having things around me from my family — these objects pop up in the books."

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

"I’d be lucky to have a morning routine! But let’s pretend… I’d get up in the morning, have breakfast, have coffee, then go upstairs to the room where I write. I’d sit down and probably start transcribing from what I’d [hand]written the day before....I’m not often in a set writing space. I don’t think there’s anything too unusual about [my study], except that it’s full of books and has two desks. On one desk there’s a computer that is not connected to the internet. On the other desk is a computer that is connected to the internet. You can see the point of that!"

"When I’m rewriting, and it’s progressing, I begin breathing audibly through my nose. I like to proofread in noisy restaurants, with my glasses off, staring close at the type. I love the feeling of sealing up a FedEx envelope — that soft, cool fibrous Tyvek bending around the corner of a block of page proofs — and sending it off. Lately, working on Traveling Sprinkler, I’ve been writing in the car, so what I see is whatever is out the windshield — usually leaves, other cars, fireflies. The dashboard is the desk, complete with coffee stains."

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

"I can’t write every day. I’m a binger. I like to go six or seven hours at a time, without a break, then go off somewhere and drink something."

"I don’t outline at all, I don’t find it useful, and I don’t like the way it boxes me in. I like the element of surprise and spontaneity, of letting the story find its own way. For this reason, I find that writing a first draft is very difficult and laborious. It is also often quite disappointing. It hardly ever turns out to be what I thought it was, and it usually falls quite short of the ideal I held in my mind when I began writing it. I love to rewrite, however. A first draft is really just a sketch on which I add layer and dimension and shade and nuance and color. Writing for me is largely about rewriting. It is during this process that I discover hidden meanings, connections, and possibilities that I missed the first time around. In rewriting, I hope to see the story getting closer to what my original hopes for it were.

"I write while my kids are at school and the house is quiet. I sequester myself in my office with mug of coffee and computer. I can't listen to music when I write, though I have tried. I pace a lot. Keep the shades drawn. I take brief breaks from writing, 2-3 minutes, by strumming badly on a guitar. I try to get 2–3 pages in per day. I write until about 2 p.m. when I go to get my kids, then I switch to Dad mode."

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

"I try to write 1000 words on a good day, about three pages. The reason for that amount, it feels right to me because most of the scenes I write are 3000-4000 words long. Not always, but on average. That means that I get 3-4 days per scene, which is good, because sometimes I’ll read it and feel — I feel different on different days, so it means I won’t have just one tone per scene. I have several different cracks at it.

"I’ll often be in the middle of writing and realize I don’t know what I’m writing about. For instance, today I’ve been writing a scene about a man who’s grafting apple trees. So I have to stop and look at my notes about grafting. Just now I was thinking, I still don’t really understand this. I need to order a book at the British Library and go and read it tomorrow. That’s what happens as I go. So what I’ll do is write a basic part of the scene, but for the grafting bit … I’ll put down three stars. Three stars in a manuscript for me means there’s something missing, I have to go back and fill it out. I don’t want it to stop my writing flow, but I’ll leave it aside and do the rest of the scene without it, come back and fill it in later. That’s a good interruption. A bad interruption is when I can’t focus and I wind up fiddling around online, having lunch with a friend, or something like that. What I’m aiming for is that concentrated time of focusing."

Writing sheds: Phillip Pullman & Linda Newbery (UK), and Michael Pollan (US)

Writing sheds: Phillip Pullman & Linda Newbery (UK), and Michael Pollan (US)

"I know many writers who try to hit a set word count every day," Russell continues, "but for me, time spent inside a fictional world tends to be a better measure of a productive writing day. I think I’m fairly generative as a writer, I can produce a lot of words, but volume is not the best metric for me. It’s more a question of, did I write for four or five hours of focused time, when I did not leave my desk, didn’t find some distraction to take me out of the world of the story? Was I able to stay put and commit to putting words down on the page, without deciding mid-sentence that it’s more important to check my email, or 'research' some question online, or clean out the science fair projects in the back for my freezer? For me, a good writing day is when I can move forward inside a story, because I take so much pleasure in tinkering with sentences that I often have to fight my own impulse to dither and revise in order to keep the momentum of the narrative going. So if I can move in a linear way through the story, and stay zipped inside the story, not jinx myself with despair or frustration or over-confidence or self-consciousness, and be basically okay with not-knowing what is going to happen from one sentence to the next, that’s a great writing day. Writers are such excellent self-saboteurs, though. I swear, I can hijack my own writing day in a hundred ways — I can eject myself from a story because I’ve decided it’s 'going good.' There’s this excruciating aspect of joy, I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced this, where you almost want to interrupt it. For me, the experience of losing myself in a character can feel intolerably wonderful. So I’ve decided that the trick is just to keep after it for several hours, regardless of your own vacillating assessment of how the writing is going....

"Showing up and staying present is a good writing day."

Neil Gaiman's writing gazebo, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Neil Gaiman's writing gazebo, Minneapolis, Minnesota

"On a shelf above my computer are five letters that spell out W-R-I-T-E. Just in case I forget why I’m there."

Are you holding it fast?

Jenny Diski wanted to be a writer, she says, "since I got the idea that each book I read was actually written by someone, that there was such a thing you could do and be in life." At fifteen years old, through a series of cirumstances, she came to live with Doris Lessing.

"Doris taught me how to be a writer," she recalls. "I don't mean she gave me lessons, or talked about writing. I can't remember her ever talking about writing, except to mumble occasionally that she was on a very difficult bit at the moment, meaning she was preoccupied, or to bellow as I thumped down the stairs past her closed door 'Be quiet. I'm working.' I was very impressed with the idea that writing was work. Even now, I always say, 'I'm working,' rather than 'I'm writing,' if anyone asks. She suggested books she thought I should read and began my instruction in the history of cinema with visits to the Academy and the National Film Theatre. But that was part of a general education of a teenager. It had nothing to do with me becoming a writer. We never talked about that. I never asked her to read anything I wrote. I learned what it was to be a writer from being around, in the house, day by day, observing her being one.

"Her morning started early when she went to the kitchen in her dressing-gown to make a cup of tea. Actually, a pint of tea in a huge blue and white striped mug, which she'd refill every couple of hours. If I happened to be up or on my way to school, she'd nod and I'd say hello, and take off. If I was at home, I'd hear the sharp clatter of keys hitting the platen. The shotgun sound of typing went on continuously for hours. She typed incredibly fast and only infrequently paused, perhaps for a sip of tea or to light a cigarette. When she did, the sudden silence was enormous, and then, whatever I was doing, I'd be on the alert, waiting for the clatter to start up again, rather like sleeping with someone with apnea when they stop breathing, and you hold your breath waiting for them to start again. She thought as she typed. And the most practical help she gave me was when she sent me to learn touch-typing, really so that I'd have secretarial skills, but, I realised quickly, by clattering myself and not having to think about typing, that it enabled the shortest possible distance between the thought in my mind and the fingers getting it on to the page.

"While she was writing, she conformed to her warning letter to me. She occasionally had supper with friends, but more or less went into what she referred to as purdah. Writing was the priority, and when something came along to interrupt – including sometimes my doings and misdoings – she dealt with it fast and efficiently, and with frequent sighs. Then she got back to work."

(I recommend Diski's full essay, published in The Guardian here.)

Lessing herself said: "Writers are often asked, How do you write? With a wordprocessor? an electric typewriter? a quill? longhand? But the essential question is, 'Have you found a space, that empty space, which should surround you when you write?' Into that space, which is like a form of listening, of attention, will come the words, the words your characters will speak, ideas - inspiration.

"If a writer cannot find this space, then poems and stories may be stillborn.

"When writers talk to each other, what they discuss is always to do with this imaginative space, this other time. 'Have you found it? Are you holding it fast?' "

Please note: If you experience problems reading or posting comments (as I'm unable to do myself), don't worry. Typepad is aware of the problem and working to correct it.

Please note: If you experience problems reading or posting comments (as I'm unable to do myself), don't worry. Typepad is aware of the problem and working to correct it.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers