Terri Windling's Blog, page 165

April 19, 2014

Tilly and I will be out of the office over the long...

Tilly and I will be out of the office over the long holiday weekend, and back again on Wednesday, April 23.

April 17, 2014

One of those days

We all have them: the off days, the slow days, the dull days, the befuddled days, the days when nothing goes quite right. The days we forget how to write, how to paint, how to sing or sculpt or design or teach or cook or parent or do much of anything creative at all; when knowledge dries up, inspiration shrivels, and we reach inward but nothing comes out. I'm not having One of Those Days right now, mind you...but I certainly will again, and sooner than I'd like, no doubt. This is part of the creative process, too, and thus deserving of our attention.

In "Why I Write," Francis Spufford describes what a bad work day feels like for him:

"[T]here’s the gluey fumbling of the attempts to gain traction on the empty screen, there’s the misshapen awkwardness of each try at a sentence (as if you’d been equipped with a random set of pieces from different jigsaws). After a time, there’s the tetchy pacing about, the increasingly bilious nibbling, the simultaneous antsiness and flatness as the failure of the day sinks in. After a longer time -- two or three or four or five days of failure -- there’s the deepening sense of being a fraud. Not only can you not write bearably now; you probably never could. Trips to bookshops become orgies of self-reproach and humiliation. Look at everybody else’s fluency. Look at the rivers of adequate prose that flow out of them. It’s obvious that you don’t belong in the company of these real writers, who write so many books, and oh such long ones. Last, there’s the depressive inertia that flows out of sustained failure at the keyboard, and infects the rest of life with grey minimalism, making it harder to answer letters, return library books, bother to cook meals not composed of pasta."

Ouch. And yet, so true.

There are days, says Neil Gaiman, "when you sit down and every word is crap. It is awful. You cannot understand how or why you are writing, what gave you the illusion or delusion that you would every have anything to say that anybody would ever want to listen to. You're not quite sure why you're wasting your time.  And if there is one thing you're sure of, it's that everything that is being written that day is rubbish. I would also note that on those days (especially if deadlines and things are involved) is that I keep writing. The following day, when I actually come to look at what has been written, I will usually look at what I did the day before, and think, 'That's not quite as bad as I remember. All I need to do is delete that line and move that sentence around and its fairly usable. It's not that bad.'

And if there is one thing you're sure of, it's that everything that is being written that day is rubbish. I would also note that on those days (especially if deadlines and things are involved) is that I keep writing. The following day, when I actually come to look at what has been written, I will usually look at what I did the day before, and think, 'That's not quite as bad as I remember. All I need to do is delete that line and move that sentence around and its fairly usable. It's not that bad.'

"What is really sad and nightmarish," Neil continues, "(and I should add, completely unfair, in every way. And I mean it -- utterly, utterly, unfair!) is that two years later, or three years later, although you will remember very well, very clearly, that there was a point in this particular scene when you hit a horrible Writer's Block from Hell, and you will also remember there was point in this particular scene where you were writing and the words dripped like magic diamonds from your fingers -- as if the Gods were speaking through you and every sentence was a thing of beauty and magic and brilliance. You can remember just as clearly that there was a point in the story, in that same scene, when the characters had turned into pathetic cardboard cut-outs and nothing they said mattered at all. You remember this very, very clearly. The problem is you are now doing a reading and you cannot for the life of you remember which bits were the gifts of the Gods and dripped from your fingers like magical words and which bits were the nightmare things you just barely created and got down on paper somehow!! Which I consider most unfair."

Douglas Rushkoff points out: "The creative process has more than one kind of expression. There’s the part you could show in a movie montage — the furious typing or painting or equation solving where the writer, artist, or mathematician accomplishes the output of the creative task. But then there’s also the part that happens invisibly, under the surface. That’s when the senses are perceiving the world, the mind and heart are thrown into some sort of dissonance, and the soul chooses to respond.

Douglas Rushkoff points out: "The creative process has more than one kind of expression. There’s the part you could show in a movie montage — the furious typing or painting or equation solving where the writer, artist, or mathematician accomplishes the output of the creative task. But then there’s also the part that happens invisibly, under the surface. That’s when the senses are perceiving the world, the mind and heart are thrown into some sort of dissonance, and the soul chooses to respond.

"That response doesn’t just come out like vomit after a bad meal. There’s not such thing as pure expression. Rather, because we live in a social world with other people whose perceptual apparatus needs to be penetrated with our ideas, we must formulate, strategize, order, and then articulate. It is that last part that is visible as output or progress, but it only represents, at best, 25 percent of the process.

"Real creativity transcends time. If you are not producing work, then chances are you have fallen into the infinite space between the ticks of the clock where reality is created."

My favorite reflection on the subject of Those Days comes from Dani Shapiro's Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of the Creative Life.

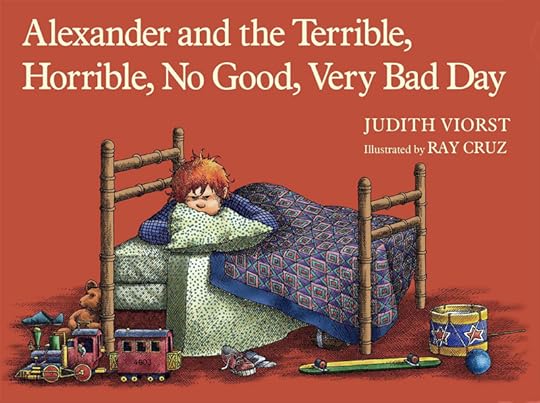

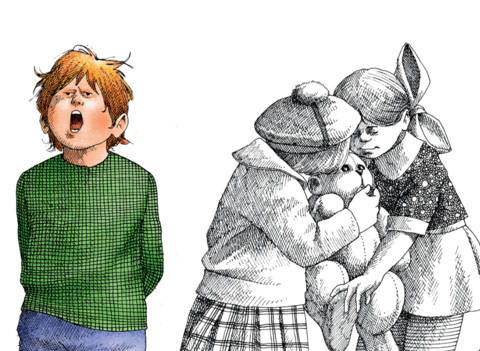

"When my son was little," she says, "he loved a book by Judith Viorst called Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. Poor Alexander. He woke up with gum in his hair, he ended up in the middle seat during carpool, his mom forgot to pack dessert in his lunch box, he had a cavity at the dentist, and just when he thought things couldn't get any worse, he saw people kissing on television. You can feel the momentum of a day turning against you, and if it does, sometimes the best thing to do is crawl back into bed and wait for it to pass.

Shapiro advises that writers (and other arts freelancers) must learn to be kind to themselves. "What we're doing isn't easy. We have chosen to spend the better part of our lives in solitude, wrestling with our deepest thoughts, obsessions and concerns. We unleash the beasts of memory; we peer into Pandora's box. We do this all in the spirit of faith and exploration, with no guarantee that what we will produce is worthwhile. We don't call in sick. We don't take mental health days. We don't get two weeks paid vacation, or summer Fridays, or holiday weekends. Often, we are out of step with the tempo of those around us. It can feel isolating and weird. And so, when the day turns against us, we might do well to follow the advice of Buddhist writer Sylvia Boorstein, who talks to herself as if she's a child she loves very much: Sweetheart, she'll say. Darling. Honey. That's all right. There, there. Go take a walk. Take a bath. Take a drive. Bake a cake. Nap a little. You'll try again tomorrow."

(For some reason I imagine this in Delia Sherman's voice, perhaps because Delia is so wise and sensible.)

Walk the dog. Read a book. You'll try again tomorrow.

And indeed, we do.

The pictures above are Ray Cruz's illustrations for Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, a very wonderful American children's book by Judith Viorst. (I often mutter "I think I'll move to Australia" when it's One of Those Days, and my English husband never knows what I mean.) Previous posts on Very Bad Days, Creative Burn-out, and Creative Blocks can be found here.

The pictures above are Ray Cruz's illustrations for Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, a very wonderful American children's book by Judith Viorst. (I often mutter "I think I'll move to Australia" when it's One of Those Days, and my English husband never knows what I mean.) Previous posts on Very Bad Days, Creative Burn-out, and Creative Blocks can be found here.

April 16, 2014

The eye and the ear

"Ancient man took in the world mainly by listening, and listening meant remembering. Thus humans both shaped and were shaped by the oral tradition. The passage of culture went from mouth to ear to mouth. The person who did not listen well, who was tone deaf to the universe, was soon dead. The finest rememberers and the most attuned listeners were valued: the poets, the storytellers, the shamans, the seers. In culture after culture, community after community, the carriers of the oral tradition were honored. For example, in ancient Ireland the ollahms, the poet-singers, were more highly thought of than the king. The king was only given importance in times of war....

"But the eye and ear are different listeners, are difference audiences. And the literary storyteller is one who must bring eye and ear into synchronization. But it is a subtle art. Just as the art of typography has been called 'the art invisible,' subliminal in the sense that it changes or manipulates the reader's perceptions without advertising its own presence, so, too, the art of storytelling in the printed book must persuade and capitvate. It must hold the reader as the spoken tale holds the listener, turning the body to stone but not the mind or heart." - Jane Yolen (Touch Magic)

"The difficulty for me in writing -- among the difficulties -- is to write language that can work quietly on a page for a reader who doesn’t hear anything. Now for that, one has to work very carefully with what is in between the words. What is not said. Which is measure, which is rhythm, and so on. So, it is what you don’t write that frequently gives what you do write its power." - Toni Morrison ("The Art of Fiction," The Paris Review)

"One method of revision that I find both loathsome and indespensible is reading my work aloud when I'm finished. There are things I can hear -- the repetition of words, a particularly flat sentence -- that I don't otherwise catch. My friend Jane Hamilton, who is a paragon of patience, has me read my novels to her once I finish. She'll lie across the sofa, eyes closed, listening, and from time to time she'll raise her hand. 'Bad metaphor,' she'll say, or 'You've already used the word inculcate.' She's never wrong." - Ann Patchett ("The Getaway Car," This is the Story of a Happy Marriage)

"I've always tried out my material on my dogs first. You know, with Angel, he sits there and listens and I get the feeling he understands everything. But with Charley, I always felt he was just waiting to get a word in edgewise. Years ago, when my red setter chewed up the manuscript of Of Mice and Men, I said at the time that the dog must have been an excellent literary critic." - John Steinbeck (Journal of a Novel)

Above: Wild daffodils in the woods, and in a jar on the kitchen table.

Above: Wild daffodils in the woods, and in a jar on the kitchen table.

Built by books

In her 2012 novel How it All Began, Penelope Lively describes her central character, Charlotte Rainsford, in a manner that many of us can relate to:

"Forever, reading has been central, the necessary fix, the support system," writes Lively. "[Charlotte's] life has been informed by reading. She has read not just for distraction, sustenance, to pass the time, but she has read in a state of primal innocence, reading for enlightenment, for instruction, even. She has read to find out how sex works, how babies are born, she has read to discover what it is to be good, or bad; she has read to find out if things are the same for others as they are for her – then, discovering that frequently they are not, she has read to find out what it is that other people experience that she is missing.

"Forever, reading has been central, the necessary fix, the support system," writes Lively. "[Charlotte's] life has been informed by reading. She has read not just for distraction, sustenance, to pass the time, but she has read in a state of primal innocence, reading for enlightenment, for instruction, even. She has read to find out how sex works, how babies are born, she has read to discover what it is to be good, or bad; she has read to find out if things are the same for others as they are for her – then, discovering that frequently they are not, she has read to find out what it is that other people experience that she is missing.

"Specifically, she read bits of the Old Testament when she was ten because of all that stuff about issues of blood, and the things thou shalt not do with thy neighbour’s wife. All of this was confusing rather than enlightening. She got hold of a copy of Fanny Hill when she was eighteen, and was aghast, but also intrigued.

"She read Rosamond Lehmann when she was nineteen, because her heart had been broken. She saw that such suffering is perhaps routine, and, while not consoled, became more stoical.

"She read Saul Bellow, in her thirties, because she wanted to know how it is to be American. After reading, she wondered if she was any wiser, and read Updike, Roth, Mary McCarthy and Alison Lurie in further pursuit of  the matter. She read to find out what it was like to be French or Russian in the nineteenth century, to be a rich New Yorker then, or a Midwestern pioneer. She read to discover how not to be Charlotte, how to escape the prison of her own mind, how to expand, and experience.

the matter. She read to find out what it was like to be French or Russian in the nineteenth century, to be a rich New Yorker then, or a Midwestern pioneer. She read to discover how not to be Charlotte, how to escape the prison of her own mind, how to expand, and experience.

"Thus has reading wound in with living, each a complement to the other. Charlotte knows herself to ride upon a great sea of words, of language, of stories and situations and information, of knowledge, some of which she can summon up, much of which is half lost, but is in there somewhere, and has had an effect on who she is and how she thinks. She is as much a product of what she has read as of the way in which she has lived; she is like millions of others built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without."

“I need fiction, I am an addict," Francis Spufford declared in his poignant memoir, The Child That Books Built. "This is not a figure of speech. I don’t quite read a novel a day, but I certainly read some of a novel every day, and usually some of several. There is always a heap of opened paperbacks face down near the bed, always something current on the kitchen table to reach for over coffee when I wake up. Colonies of prose have formed in the bathroom and in the dimness of the upstairs landing, so that I don’t go without text even in the leftover spaces of the house where I spend least time….I can be happy with an essay or a history if it interlaces like a narrative, if its author uses fact or impression to make a story-like sense, but fiction is kind, fiction is the true stuff....I don’t give it up. It is entwined too deeply within my history, it has been forming the way I see for too long."

"Reading was my escape and my comfort, " Paul Aster concurs, "my consolation, my stimulant of choice: reading for the pure pleasure of it, for the beautiful stillness that surrounds you when you hear an author's words reverberating in your head.”

"When I got [my] library card, that was when my life began," says Rita Mae Brown, and I know just what she means.

Thus I've been surprised (and a little alarmed) recently by conversations in several of the different spheres I inhabit in which smart, creative people admit that they haven't read many books (in some cases, any books) in a long while. My god, I keep thinking, if artistic and literary friends aren't reading, what hope for the rest of our culture?

Not reading is something I can't really fathom. I'm not boasting here; my reading habit is compulsive, like Spufford's, bordering on obsession, and I'd spend my last dollar on a book, not food. (I know this, because I occasionally did so in the difficult days of my youth.) I cannot imagine how I would survive were I confined to this one single life, this one problematic body, this one limited, fragile consciousness, instead of roaming the wide, wondrous world through the magic of ink and the alphabet.

There's a famous scene (famous to bookish folks, anyway) in the American television show The Gilmore Girls in which teenaged Rory fills her backpack with books to read before catching the bus to school...explaining to her mother that she needs a pack big enough for all of them because each one --  a novel, a biography, short stories, essays, etc. -- is necessary for different reading moods. (This was pre-Kindle, of course.) My housemate found it hilarious since it was the way I loaded my backpack too; and one of my great fears in life is being stuck somewhere with nothing to read. Oh, the horror!

a novel, a biography, short stories, essays, etc. -- is necessary for different reading moods. (This was pre-Kindle, of course.) My housemate found it hilarious since it was the way I loaded my backpack too; and one of my great fears in life is being stuck somewhere with nothing to read. Oh, the horror!

"Writing is a form of therapy," said Graham Greene; "sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose, or paint can manage to escape the madness, melancholia, the panic and fear which is inherent in a human situation." Greene's words can apply to reading too--

I was about to write: "since I don't know how people can cope without reading." But in fact I do know, for I once spent several months unable to read (or to write) while recovering from meningitis, which affected both my vision and my ability to concentrate on the linear unfolding of a text. Even audiobooks were too hard to follow; I was reduced to watching old episodes of Buffy and Angel: simple, visual, and familiar enough that I could waver in and out of the story. I recall saying over and over to friends: I just don't feel like me. Who am I, if I'm not reading or writing? It was, I am very glad to say, a temporary experience -- but profoundly unsettling, and just plain profound. It is frightening, yes, but also enlightening when life strips away those things that we most depend on...and then gives them back again.

Even stranger than hearing that literary friends are no longer reading (or read only online) is meeting aspiring writers who rarely read...and this happens much more often than you'd think. The key word is "aspiring," however -- for I can't recall a single one of the many successful writers I've edited over the years who wasn't also a passionate reader of books, of one sort or another. Such alien creatures must exist, somewhere, since all things are possible under the sun, but I don't know how I'd work with a non-bookish writer. What common language would be speak?

Of course, sometimes when a novelist is at work, he or she will avoid reading some books or authors in order to avoid certain kinds of influence (a rhythm of prose that interfere with one's own, for example) -- although this varies from writer to writer, and also between one stage of writing and another. For me, when I'm on a first or last draft, I tend to limit the amount of fiction I'm reading (making up for it with nonfiction instead) so that my narrative voice is not overlayed by another fiction writer's style...but for in-between drafts I can, and do, read pretty much anything. I'm not worried, then, about influence; on the contrary, I seek it out: learning this from one writer and that from another; inspired by good books, educated (on what to avoid) by bad ones; filling the well so that the internal Waters of Story will never run dry.

"A great painting, or symphony, or play, doesn't diminish us," assures Madeleine L'Engle, "but enlarges us, and we, too, want to make our own cry of affirmation to the power of creation behind the universe. This surge of creativity has nothing to do with competition, or degree of talent. When I hear a superb pianist, I can't wait to get to my own piano, and I play about as well now as I did when I was ten. A great novel, rather than discouraging me, simply makes me want to write. This response on the part of any artist is the need to make incarnate the new awareness we have been granted through the genius of someone else."

"Read, read, read," advised William Faulkner. "Read everything -- trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You'll absorb it. Then write. If it's good, you'll find out. If it's not, throw it out of the window."

James Baldwin was also a child "built by books," in New York City during the '20s and '30s. "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read," he recalled. "It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive."

"Reading is the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another's skin, another's voice, another's soul," says Joyce Carol Oates.

Or as Betty Smith wrote in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943): "The world was hers for the reading."

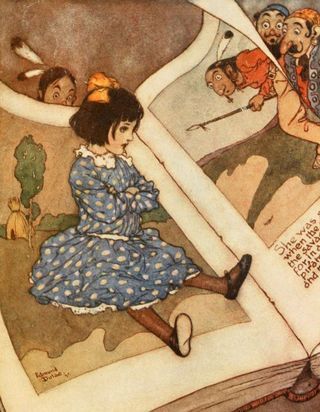

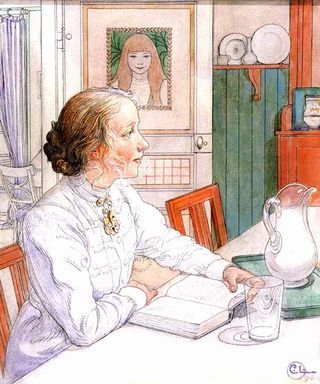

Images above: "The Good Book" by Katherine Cameron (1874-1965), "Little Girl in a Book" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), pen & ink drawing by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), The Fairy Garland illustrated by Edmund Dulac, three paintings by

Carl Larsson (1853-1919)

, "Making Paper Dolls" by Arthur Rackham, and two old photgraphs: boys in front of the Public Library in Cincinatti, Ohio (exact date unknown), and Holland House Library in London during the Blitz (1940).

Images above: "The Good Book" by Katherine Cameron (1874-1965), "Little Girl in a Book" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), pen & ink drawing by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), The Fairy Garland illustrated by Edmund Dulac, three paintings by

Carl Larsson (1853-1919)

, "Making Paper Dolls" by Arthur Rackham, and two old photgraphs: boys in front of the Public Library in Cincinatti, Ohio (exact date unknown), and Holland House Library in London during the Blitz (1940).

April 14, 2014

The glassy hill

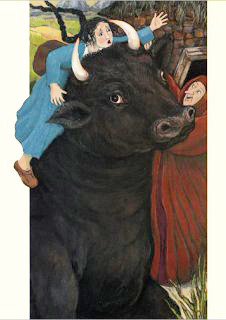

Today, two poems based on related fairy tales: "The Black Bull of Noroway," from England, and "East of the Sun, West of the Moon," from Scandinavia....

Norroway in February by Hannah Sanghee Park

by Hannah Sanghee Park

The glassy hill I clomb for thee

For surefooted step, hooves behoove the haver.

The sky redid blue, the woman wavered,

and the black bull (the vanquisher), vanished.

She called out to nothing, and in vain shed

tears until she reached the glass hill’s impasse.

Served her standard fairy tale penance, passim,

served her seven to be given iron

shoes to — at last — scale the hill, the earned

neared end. Each step conquered territory, at last, the sleeping prince-once-bull, torrid tearing

at last, the sleeping prince-once-bull, torrid tearing

of clothes, tearing on one’s clothes, three nights of this

until the prince awakes. How she, exhausted,

must have felt in the at long last, the ever after.

Happily, I guess, but a long time until laughter.

- Published in the November 2013 issue of Poetry magazine.

An excerpt from

An excerpt from

The Seven Pairs of Iron Shoes

by Tracina Jackson-Adams

The first pair of shoes I wore out

was for your forgiveness. Racked with guilt,

I pursued you with single intent,

barely ate or slept, accepted the heat,

the cold, the wet misery and stumbling weariness

as my due. I had failed you. It was only just.

Throughout the second pair, I hated you.

I followed you only because I forgot I could stop.

Many places looked familiar by the third pair,

and I found I knew the coming weather by the taste

of the wind. I was no longer afraid of snakes,

and I placed my feet with care

So as not to trample small things. By the fourth,

I moved silently and did not realize it.

From then on, I roamed for wonder alone,

and slipped through the years like a wolf

through tall grass. I had long since stopped counting

through tall grass. I had long since stopped counting

when I heard stories of a land east

of the sun and west of the moon,

and I thought, there's a place I haven't walked to yet....

- Published in Star*Line magazine, issue number 25.2, 2002, & reprinted in The Year's Best Fantasy & Horror, Vol. 16, 2003. The full text of the poem can be found online on various blogs such as this one -- though I don't know if it's ever appeared online with the author's permission, which is why I use an excerpt only here. I do recommend seeking out the full poem; it's a wonderful (and wonderfully sensible) reworking of the fairy tale theme.

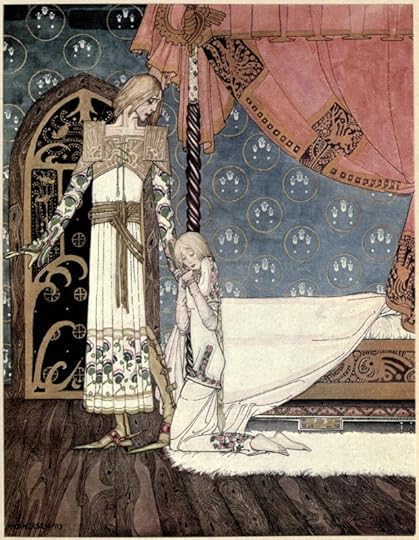

Art above: "Black Bull of Norroway" illustration by John D. Batten (1860-1932), two "Black Bull of Norroway" illustrations by Anita Lobel, three "East of Sun, West of the Moon" illustrations by Kay Nielsen (1886-1957), and another "Black Bull of Norroway" illustration by John D. Batten. All rights to Anita Lobel's art and the two poems above are reserved by their creators.

April 13, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

As I go through a stretch of time with some difficult things to contend with (and I'm sorry I can't be more explicit than that in this public forum), I'm grateful for the ways that music can lift the spirits even on the most daunting of days. One of the albums in heavy rotation in my studio lately is Sing to the Moon, last year's debut release by singer/songwriter Laura Mvula, from Birmingham, UK. Mvula's gorgeously multi-layered music -- rooted in soul, jazz, and gospel, but also rich in influences from English and African folk music and other worldwide musical genres -- is powerful medicine indeed.

April is National Child Abuse Prevention Month, so the beautiful song above -- "She," filmed in South Africa -- goes out to all of the good people who work with abused, neglected, homeless, and traumatized kids the world over. Including an incredible organization that I just learned about from my husband, Clowns Without Borders...

...a federation of clowns from Belgium, Canada, England, France, Germany, Ireland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and the U.S., dedicated to bringing laughter to children in war zones, refugee camps, and other places where communities are in crisis.The whole thing was started by Tortell Poltrona, a clown from Barcelona, after performing for children in war-ravaged Croatia in 1993. (You can read more about it in Mark Hay's recent article for Vice magazine.)

Getting back to the music....

Below, Mvula performs her album's title song, "Sing to the Moon," at the Full Future Festival in 2012.

Next:

"Green Garden," peformed last year for the BBC's Sound of 2013.

And last, a fabulous video for yet another fabulous song: "That's Alright."

Oh how I wish this one could be the personal anthem of every young girl -- and indeed, every young boy -- growing up amidst the narrow, poisonous definition of beauty so pervasive in our media culture today.

Bless you, Laura Mvula, for your strength, wisdom, and true beauty.

April 10, 2014

Madeleine L'Engle on writing and courage

"It's a good thing to have all the props pulled out from under us occasionally. It gives us some sense of what is rock under our feet, and what is sand."

- Madeleine L'Engle (Crosswicks Journal 3: The Summer of the Great-Grandmother)

"If I never had another book published, and it was very clear to me that this was a real possibility, I still had to go on writing. I'm glad I made this decision in a moment of failure. It's easy to say you're a writer when things are going well. When the decision is made in the abyss, then it is quite clear that it is not one's own decision at all."

- Madeleine L'Engle (Crosswicks Journal 1: A Circle of Quiet)

"I write for the child in everybody, that part of us that is aware and open and courageous. It's also that part of us that isn't afraid to explore the mythical depths, that vast part of ourselves we know little about and which we often fear because we can't manipulate or control it. That's where art is born."

- Madeleine L'Engle (Crosswicks Journal 3: The Irrational Season)

The freedom of the trail

In The Seven Secrets of the Prolific (a very practical guide to overcoming procrastination, perfectionism, and writers' blocks), Hillary Rettig proposes a "trail metaphor" of writing:

"Picture your writing session as a stroll down a beautiful, sun-dappled woodland path....All of a sudden someone pops up out of the underbrush and joins you on your path -- it's your husband, full of opinions on your current writing." As you walk on, your parents join you, your siblings, an old teacher, a critical editor, all yammering in your ear with opinions, worries, criticisms of your work. "Soon, you're walking at center of crowd, none of whom you've invited."

The prolific handle things differently, she explains. "They decide, with absolute authority...who comes on their path and how long they can stay. You're only allowed on if they want you on, and the minute you're no longer an asset to their process, you're gone....And no free passes -- everyone has to pass the 'asset' test, including partners, parents, kids, and 'important' teachers, editors, and the like. And those who fail a few times permanently lose their right to apply for entry.

"They're banished, baby.

"And so the prolific have a wonderful time strolling peacefully and productively through the hours, days, and years of their work."

The painter Philip Guston (1913-1980) described a similar process. Everyone followed him into the studio: his family, colleagues, mentors, critics, friends, enemies, everyone. But as Guston worked they all left again, emptying the studio one by one. On a good day, he said, I am finally alone; and on a really good day, even I leave the room.

"When the work takes over," wrote Madeleine L'Engle (in Walk on Water), "then the artist is enabled to get out of the way, not to interfere."

"Remember as you begin," Dani Shapiro advises (in Still Writing) "that you are in a remote and exotic place -- the literary equivalent of far eastern Bhutan. It is a place where no one can find you. Where anything is possible. Where, for a time, you are free, liberated from the expectations and ideas of others. You are trekking and the vistas are infinite. This freedom is necessary whether you're working on your first book or your tenth. In order to create a world on the page, you need to push away from the world around you. You must forget its expectations and constraints."

"So what it is about writing that makes it -- for some of us -- as necessary as breathing?" asks Shapiro. "It is in the thousand days of trying, failing, sitting, thinking, resisting, dreaming, raveling, unraveling that we are at our most engaged, alert, and alive. Time slips away. The body becomes irrelevant. We are as close to consciousness itself as we will ever be. This begins in the darkness. Beneath the frozen ground, buried deep below anything we can see, something may be taking root. Stay there, if you can. Don't resist. Don't force it, but don't run away. Endure. Be patient. The rewards cannot be measured. Not now. But whatever happens, any writer will tell you: This is the best part."

The books quoted above are: The Seven Secrets of the Prolific: The Definitive Guide to Overcoming Procastination, Perfectionism, and Writers' Block by Hillary Rettig (Infinite Art, 2011),

Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life by Danio Shapiro (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013) , and Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art by Madeleine L'Engle (Northpoint Press, 1995).

The books quoted above are: The Seven Secrets of the Prolific: The Definitive Guide to Overcoming Procastination, Perfectionism, and Writers' Block by Hillary Rettig (Infinite Art, 2011),

Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life by Danio Shapiro (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013) , and Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art by Madeleine L'Engle (Northpoint Press, 1995).

April 8, 2014

The path through the woods

''To write is to carve a new path through the terrain of the imagination, or to point out new features on a familiar route. To read is to travel through that terrain with the author as a guide - a guide one might not always agree with or trust, but who can at least be counted on to take one somewhere.''

- Rebecca Solnit (Wanderlust)

''Does the walker choose the path, or the path the walker?''

- Garth Nix (Sabriel)

"All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveler is unaware."

So at the end of this day, we give thanks

For being betrothed to the unknown.

T

he beautiful paintings above are illustrations for Tolkien's Lord of the Rings and Peter Dickinson's Merlin Dreams by Alan Lee. A look at the dark side of woodland journeys can be found in this previous post: The Dark Forest.

T

he beautiful paintings above are illustrations for Tolkien's Lord of the Rings and Peter Dickinson's Merlin Dreams by Alan Lee. A look at the dark side of woodland journeys can be found in this previous post: The Dark Forest.

April 7, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's songs are all by Bob Dylan, covered by various musicians. This post is in honor of Howard's return from Portugal, as he's a massive Dylan fan.

Above, a lovely version of "Girl from the North Country" (audio only) performed by the young English folksinger and fiddle player Jackie Oates, formely based here in Devon and now up in Oxford. Oates has four good solo albums to date, and has peformed with Rachel Unthank and the Winterset (before the band regrouped as The Unthanks) and The Imagined Village.

Dala also does a great cover of "Girl from the North Country." Alas, I can't find a good recording of it to link to, but here's an amazing blast from the past: Joni Mitchell and the late, great Johnny Cash perform the song as a duet, filmed back in the '70s. The video is a little blurry...but what a combination!

Below, "Boots of Spanish Leather" peformed by Wesley Schultz of The Lumineers, the alt-folk band out of Denver, Colorado.

Nanci Griffith's classic version of "Boots of Spanish Leather" is here. And the Lumineers' cover of another Dylan song, "Subterranean Homesick Blues," is here.

Next, Canadian folksinger Frazey Ford performs a bluesy cover of "One More Cup of Coffee" for BBC Scotland. Ford is a founding member of the fabulous female folk trio The Be Good Tanyas, and released a solo album, Obadiah, in 2010.

And last:

"Man Gave Names to all the Animals" performed by Johnny Borrell from the English indie rock band Razorlight. I love this one.

It's good to be back in the studio, and back on Myth & Moor -- but my time is still being taken up by some rather pressing Big Life Stuff, and I might not manage a daily post this week. On the other hand, I might...depending on how the week goes. Thanks for your patience, gentle Readers.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers