Terri Windling's Blog, page 168

March 6, 2014

Being normal is over-rated

From Writing Still: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life by Dani Shapiro (which I highly recommend):

"I need to live by certain rules in order to protect my writing life. When I was starting out, I didn't understand this. A friend would call and ask me to lunch or, worse, breakfast, and I'd jump at the chance to get away from my desk for a couple of hours and join the world of real people eating real meals. I convinced myself that I had enough disciplin to go out for a bit and then return to my desk, perhaps even invigorated and refreshed...and then, an hour or two later, I'd discover that my work day was over....

"I need to live by certain rules in order to protect my writing life. When I was starting out, I didn't understand this. A friend would call and ask me to lunch or, worse, breakfast, and I'd jump at the chance to get away from my desk for a couple of hours and join the world of real people eating real meals. I convinced myself that I had enough disciplin to go out for a bit and then return to my desk, perhaps even invigorated and refreshed...and then, an hour or two later, I'd discover that my work day was over....

"Our work requires us to adhere to certain rules -- not because we're rigid or self-absorbed as frustrated friends or family might secretly think -- but because it's the only way we can do it. If we are deep inside a story, we're in another world -- the world we've created -- which, for the time being, is where we need to live if we are to make it real to ourselves and, ultimately, to others.

"I used to be angry with myself for my inability to live a normal life with normal rhythms and also be a writer. But I've come to believe that normal is over-rated -- for artists, for everyone. When I was writing Devotion, all but the most essential tasks fell away. My hair got too long; I skipped my annual mammogram; the dogs' nails went unclipped; the windows didn't get cleaned; I lost touch with friends. But I took care of my family, and my book got written. That was all I could manage....

"Be a good steward to your gift. This is the first sentence on a list I keep tacked to the bulletin board in my  study, an impeccable set of instructions left by the poet Jane Kenyon.

study, an impeccable set of instructions left by the poet Jane Kenyon.

* Protect your time.

* Feed your inner life.

* Avoid too much noise.

* Read good books, have good sentences

in your ears.

* Be by yourself as often as you can.

* Walk.

* Take the phone off the hook.

* Work regular hours.

"...Culivate solitude in your writing space, your car, at the kitchen table when the house is empty. Get your blood moving, get your feet on the earth. Your mind is not floating in space but connected to a body. Kenyon wrote this before the lure of the Internet became like crack cocaine for most writers so I would add, 'Disable the Internet.' Find a rhythm. This is wisdom from a poet who died too young. I never knew her but she has helped me as much as anyone I have ever known."

(For another writer's list of personal instructions, see Henry Miller's in this previous post.)

From Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson (also highly recommended):

"I had lines inside me, a string of guiding lights. I had language. Fiction and poetry are doses, medicines. What they heal is the rupture reality makes on the imagination. I had been damaged, and a very important part of me had been destroyed -- that was my reality, the facts of my life. But on the other side of the facts was who I could be, how I could feel. And as long as I had words for that, images for that, stories for that, then I wasn't lost."

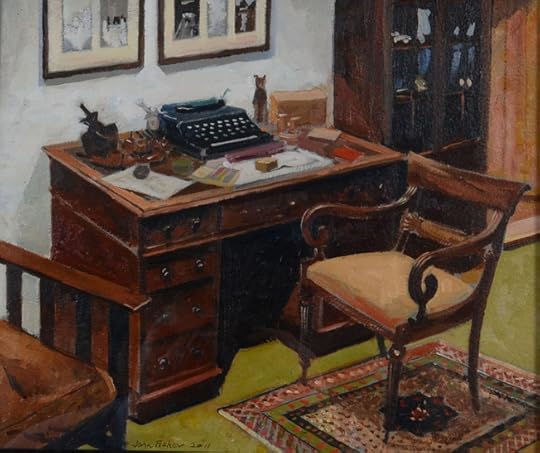

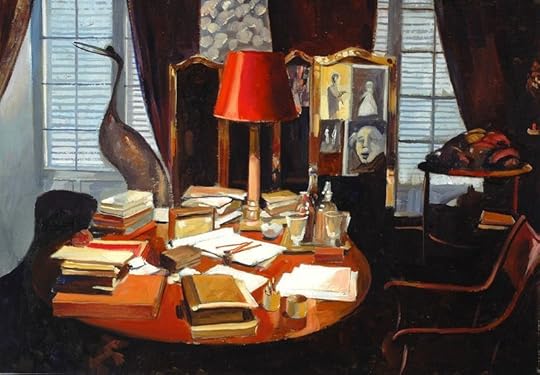

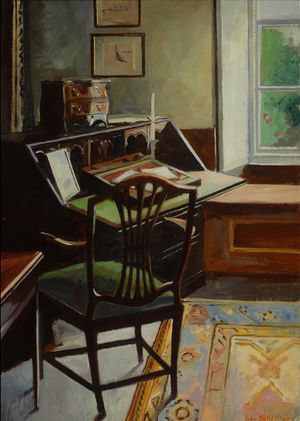

The art above is by the English painter John Fisher, from his wonderful series on writers' rooms.

"Freud once suggested that a house, when summoned in a dream, represents the soul of a dreamer," says Fisher. "This is certainly true of writers, who make a profession of dreaming, and whose houses often reflect their spirit long after they have departed the premises. I’ve always been fascinated by houses where writers have lived and worked, and have made far-flung pilgrimages to many of these sites of significant dreaming. One longs to sit in these houses, to wander their dark corridors and look out of their windows, to observe their peculiar angle of vision on the outside world."

March 4, 2014

Taking Our Own Hands

In her lovely book Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life, Dani Shapiro tackles a subject that will be familiar to many writers and other creative folks: the feeling that we somehow need "permission" to pull ourselves away from other tasks and sit down to do our heart's work.

"If you're waiting for the green light, the go-ahead, the reassuring wand to tap your shoulder and anoint you as a writer," she says, "you'd better pull out your thermos and folding chair because you're going to be waiting for a good long while. Accountants go to business school and when they graduate with their degrees, they don't ask themselves whether they have permission to do people's taxes. Lawyers pass the bar, medical students become doctors, academics become professors, all without considering whether or not they have the right to be going to work. But nothing and no one gives us permission to wake up and sit at home staring at a computer screen while everybody else sets their alarm clock, puts on reasonable attire, and boards the train....

"Sure, there are advanced degrees in writing and various signifiers that a career might be underway, but ultimately a writer is someone who writes. A writer who writes is someone who finds the way to give herself permission. The advanced degree is useless in this regard. No writer I know wakes up in the morning and, while brushing her teeth, thinks: Check me out, I have an MFA. Or, for that matter, I've published x number of books, or even, I've won the Pulitzer Prize. There is no magical place of arrival. There is only the solitary writer facing the page."

"Whether you are a writer just mustering up the nerve to sign up for your first weekend workshop," Shapiro continues, "or filling out your MFA applications, or one gazing moodily out from a big poster in the window of your local Barnes & Noble, you are far from alone in this business of granting yourself the permission to do your work. Masters of the form quake before the page. They often feel hopeless and despairing. They may also fall prey to petty musings. They have days in which they simply can't get out of their own way.

"But when we give ourselves permission, we move past this. The world once again reveals itself to us. We become open and aware, patient and ready to receive it....We give ourselves permission because we are the only ones who can do so."

Shapiro's good advice actually applies to many things in life besides writing, for there are all sorts of ways we can hold ourselves back from the things we need most to be doing. Most importantly, we must give ourselves "permission" to be the person we truly are -- as opposed to who we thought we'd be, or were raised to be, or who others would very much like us to be -- and no one else can do this for us. Teachers, mentors, partners, friends can provide support in various ways, but permission has to come from within if we are to own our lives, and our art.

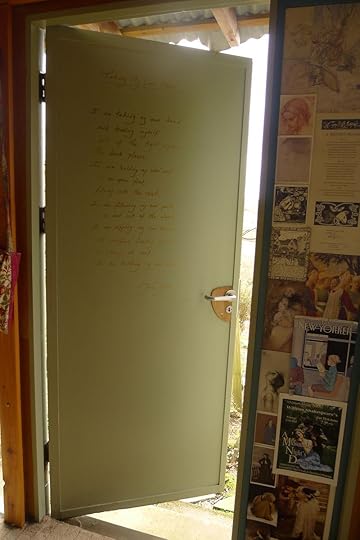

I started this post with a photograph of my studio door, which is where I write a favorite poem each month. (The gold ink washes off with white spirit, allowing me to change the poems as often as I want to.) Many of the poems Jane Yolen has shared on this blog have ended up here...including the one below, chosen for the month of March. It's been on the door before, but it's worth repeating, and it feels just right today.

In the photo above, Tilly looks out over the hills and waits for spring to arrive. The poem on the studio door, "Taking My Own Hand," is © 2012 by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. The Bunny Girl on my desk is by Wendy Froud.

In the photo above, Tilly looks out over the hills and waits for spring to arrive. The poem on the studio door, "Taking My Own Hand," is © 2012 by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. The Bunny Girl on my desk is by Wendy Froud.

March 3, 2014

Signs of spring

Well, it's official: it's been the wettest winter here in England in 250 years; and we're all just about as weary as we can be of grey skies, flooded gardens, leaky houses, mud-covered Wellies, and raincoats constantly drip-drying by the hearth. But spring is coming. Snowdrops are blooming and the wild daffodils are poking through the leaf mulch in the woods.

Every year as the first of the flowers emerge like miracles from the cold, dark earth, I'm reminded of these words from Anaïs Nin, for every year they seem to be relevant once again:

"The day came," she said, "when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom."

For me, I've decided that day is now. I've been solitary lately, quietly grieving, giving the end my Arizona life a proper mourning. But it's time to emerge from the dark days of winter, unfurl like the flowers and re-commit to life and art.

And what about you?

What have you been holding back on?

What have you been waiting to start, or change...

...and when will you finally be ready, if not now?

Winter's not yet over, and the rain keeps falling. But signs of spring are everywhere I look.

Some encouraging words for awakening after winter hibernation: Lean In, 2 (What Would You Do if You Weren't Afraid?), "Why One Writes," "On Beginnings," and "The Best Time to Begin," posted previously on Myth & Moor. "Fearless Women" by Theodora Goss. "18 Principles for Highly Creative Living" and "The Art of Creative Abundance" by Justine Munk. Creative goal-setting with Grace Nuth at the Domythic Bliss blog during "Mythic March." And since this is such a woman-centric list, here's Scott Sonnon's inspiring letter to his 9-year-old son, "Rules of Engagement for Becoming a Man," on The Good Men Project website.

Recommended Reading

I hightly recommend Rebecca Mead's "George Eliot, Middlemarch and Me" (which you can read in The New Yorker or The Guardian), which beautifully illustrates the value of returning to favorite novels (if they're good ones) at different points in our lives.

I hightly recommend Rebecca Mead's "George Eliot, Middlemarch and Me" (which you can read in The New Yorker or The Guardian), which beautifully illustrates the value of returning to favorite novels (if they're good ones) at different points in our lives.

"[I]n revisiting Middlemarch in middle age," writes Mead, "the melancholy I experience in reading its final pages is augmented by a strange glimmer of hope, even optimism. I see in it now what I could not see as a young person: that wisdom is always being acquired, and is never fully accomplished; that love can arrive in unimagined ways, and may be found where we least expect it."

Indeed.

There are a number of authors I re-read this way, getting new things out of their books each time -- but I haven't returned to Middlemarch in ages. I'm now inspired to pull it off the shelves again...and to order Mead's intriguing new book, My Life in Middlemarch.

The illustration above is by Pierre Mornet.

March 2, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's music comes from Dartmoor's own Seth Lakeman, who lives across the moor near Tavistock. I've been listening to his new CD, Word of Mouth, all weekend (thank you for the present, Howard!) and it's simply stunning.

As a songwriter, Lakeman draws inspiration from the myths, folklore, and history of Devon and Cornwall. This album, recorded in an old Cornish church, is focused on "hidden histories and unsung everyday heroes," telling the stories of soldiers, miners, dockyard workers, Travellers, and others. (The Special Edition of the album intercuts songs with excerpts from the interviews they're based on. There's a very good article about the genesis of the album here.) I deeply admire this man's music not only for its energy and fabulous sound, but also for the intelligence, care, and love for the West Country that he puts into every new recording.

The first two songs today are from Word of Mouth. Above, the newly-released video for "Courier," about ancient tracks on Dartmoor. Below, Lakeman's version of "Portrait of My Wife," a traditional English folksong derived from the Frank Kidson Broadside Collection, performed at the historic St James's Church (designed by Christopher Wren) in central London.

The next two videos feature songs from his first CD, Kitty Jay, which focused on lore and legends of Dartmoor.

Below, an orchestrated version of "The Bold Knight" (as opposed to the simple, stripped-down version on the album), performed with the BBC Concert Orchestra at the Plymouth Pavillions on the southern coast of Devon.

And last:

"Kitty Jay" performed at The Minack Theatre in Cornwall, a gorgeous open-air performance space right by the sea. The song is based on the legend of Kitty Jay (whose grave is just a short drive from here), played with the bow-shredding intensity Lakeman is well known for.

Kitty Jay's Grave, near Manaton and Hound Tor. (Wikimedia Commons photographs)

Kitty Jay's Grave, near Manaton and Hound Tor. (Wikimedia Commons photographs)

February 28, 2014

Want to name a goat?

Well, here's your chance . It's one of the inducements offered (for a £45.00 pledge) in the Chagford Community Farm Crowdfunding Campaign...along with the satisfaction of supporting the Local Food Renaissance here in south-west England.

The video above explains the campaign (and gives you a glimpse of the Chagford countryside). Follow this link to learn more about the nonprofit Chagford Community Farm (a.k.a. Chagfarm, founded by brothers Davon and Sylvan Friend)....not to be confused with the Chagfood Community Market Garden (a.k.a. Chagfood, about whom I have posted before), although the two groups often work together. Howard and I are members of both.

February 27, 2014

Stepping into the unknown

From "Escaping Into Ourselves" by Susan Cooper (Celebrating Children's Books, 1981):

"Perhaps I speak only for myself, perhaps it's different for other writers; but for me, the making of a fantasy is quite unlike the relatively ordered procedure of writing any other kind of book. I've never actually thought: 'I am writing fantasy'; one simply sits down to write whatever book is knocking to be let out. But in hindsight, I can see the peculiar differences in approach. When working on a book which turns out to be a fantasy novel, I exist in a state of continual astonishment. The work begins with a deep breath  and a blindly trusting step into the unknown; I know where I'm going, and who's going with me, but I have no real idea of what I shall find along the way, or whom I'll meet. Each time, I am striking out into a strange land, listening for the music that will tell me which way to go. And I am always overcome by wonder, and a kind of unfocused gratitude, when I arrive; and I always think of Eliot:

and a blindly trusting step into the unknown; I know where I'm going, and who's going with me, but I have no real idea of what I shall find along the way, or whom I'll meet. Each time, I am striking out into a strange land, listening for the music that will tell me which way to go. And I am always overcome by wonder, and a kind of unfocused gratitude, when I arrive; and I always think of Eliot:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time....

"One of the best 'realistic' novelists (how I hate labels -- but there's no way round them) said to me once, cheerfully rude, 'Oh, you fantasy people have it so easy, you don't know you're born. If there's  a problem in your plot -- bingo, you bring in a bit of magic and the problem's gone.

a problem in your plot -- bingo, you bring in a bit of magic and the problem's gone.

"No, no, no, fantasy doesn't work that way; anyone cherishing such theories is bound for trouble. If he or she tries to sail our perilous seas in such a ship, he is likely to end up with a book which may be beautifully written, hugely entertaining, full of bits of magic -- but which somehow isn't fantasy. True fantasy is John Masefield's The Box of Delights, or Alan Garner's The Owl Service: books which cast a spell so subtle and overwhelming that it has overpowered the reader's imagination, carried him outside all the rules, before he has noticed what is happening. To some degree I doubt whether Masefield or Garner or the rest knew what was happening either; they simply heard the music, and employed all their considerable talent to write it down. You can't write fantasy on purpose. Like poetry, it is a kind of happy accident which overtakes certain writers before they are born."

The pictures above are: "Carrying her Train (from The Happy Prince)," "Beauty and the Beast," "Hans in his Garden (from The Happy Prince)," "Casting a Spell," and "The Lion in Love" by Charles Robinson (1870-1937). He was the son of an illustrator, and his brothers Thomas Heath Robinson and William Heath Robinson were also illustrators.

The pictures above are: "Carrying her Train (from The Happy Prince)," "Beauty and the Beast," "Hans in his Garden (from The Happy Prince)," "Casting a Spell," and "The Lion in Love" by Charles Robinson (1870-1937). He was the son of an illustrator, and his brothers Thomas Heath Robinson and William Heath Robinson were also illustrators.

February 26, 2014

Re-shaping reality

From an article on fantasy literature for children by Lloyd Alexander (The Horn Book magazine, 1968):

"All art, by definition of the word, is fantasy in the largest sense. The most uncompromisingly (shall I say sordidly?) naturalistic novel is still a manipulation of reality. Fantasy, too, is a manipulation, a re-shaping of reality. There is no essential conflict or contradiction between literary realism and literary fantasy, no more than between science and humanism. Technical details aside, most of the things you can say about fantasy also apply to realism. I suppose you might define realism as fantasy pretending to be true; and fantasy as reality pretending to be a dream.

"Of course, for practical reasons -- and librarians and teachers understand these better than anyone -- we are obliged to catagorize and separate. Like it or not, we become specialists. The best we can do is make sure we are not nearsighted specialists. We can always keep in the back of our minds the idea that whatever our specialty, it is still an integral part of the whole. Literature for children is not a quiet backwater, but a current of the mainstream."

From Ursula K. Le Guin's acceptance speech for the National Book Award for Young People's Literature (received for the third of her "Earthsea" books, The Farthest Shore, 1973):

"We who hobnob with hobbits and tell tales about little green men are used to being dismissed as mere entertainers, or sternly disapproved of as escapists. But I think perhaps the catagories are changing, like the times. Sophisticated readers are accepting the fact that an improbable and unmanageable world is going to produce an improbable and hypothetical art. At this point, realism is perhaps the least adequate means of understanding or portraying the incredible realities of our existence. A scientist who creates a monster in the laboratory; a librarian in the library of Babel; a wizard unable to cast a spell; a space ship having trouble getting to Alpha Centauri: all these may be precise and profound metaphors of the human condition. Fantasists, whether they use ancient archetypes of myth and legend or the younger ones of science and technology, may be talking as seriously as any sociologist -- and a good deal more directly -- about human life as it is lived, and as it might be lived. For after all, as great scientists have said and as all children know, it is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope."

From Alison Lurie's collection of essays on children's literature, Don't Tell the Grown-ups (1990):

''The great subversive works of children's literature suggest that there are other views of human life besides those of shopping malls and the corporation. They mock current assumptions and express the imaginative, unconventional, noncommercial view of the world in its simplest and purest form. They appeal to the imaginative, questioning, rebellious child within all of us, renew our instinctive energy, and act as a force for change. This is why such literature is worthy of our attention and will endure long after more conventional tales have been forgotten.''

From Andre Norton's The Book of Andre Norton (1975):

"There is no more imagination-stretching form of writing, nor reading, than the world of fantasy. The heroes, heroines, colors, action, linger in one's mind long after the book is laid aside. And how wonderful it would be if world gates did exist and one could walk into Middle Earth, Kavin's World, the Land of Unreason, Atlantis, and all the other never-nevers! We have the windows to such worlds and must be content with those."

February 25, 2014

Why we need fantasy

"Dealing with the impossible, fantasy can show us what may really be possible. If there is grief, there is the possibility of consolation; if hurt, the possibility of healing; and above all, the curative power of hope. If fantasy speaks to us as we are, it also speaks to us as we might be." - Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007)

"Fantasy is escapism, but wait.... Why is this wrong? What are you escaping from, and where are you escaping to? Is the story opening windows or slamming doors? The British author G.K. Chesterton summarized the role of fantasy very well. He said its purpose was to take the everyday, commonplace world and lift it up and turn it around and show it to us from a different perspective, so that once again we see it for the first time and realize how marvelous it is. Fantasy -- the ability to envisage the world in many different ways -- is one of the skills that make us human." - Terry Pratchett

"From their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, they continually cope with frustrations as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things." - Maurice Sendak (1928-20012)

"When we are children, we have a tranquil acceptance of mystery which is driven out of us later on, by curiosity and education and experience. But it is possible to find one's way back. With affection and respect, I disagree totally with Penelope Lively's conviction about the 'absolute impossibility of recovering a child's vision.' There are ways, imperfect, partial, fleeting, of looking again at a mystery through the eyes we used to have. Children are not different animals. They are us, not yet wearing our heavy jacket of time." - Susan Cooper

To hear Lloyd Alexander, Terry Pratchett, Maurice Sendak and Susan Cooper speak about fantasy, imagination, and their work, follow the links above.  Other quotes on fantasy can be found here, here, and here. For quotes about fantasy in books for children: "The Forest of Stories" Parts I, II, and III. The illustrations above are by Richard Doyle (1824-1883).

Other quotes on fantasy can be found here, here, and here. For quotes about fantasy in books for children: "The Forest of Stories" Parts I, II, and III. The illustrations above are by Richard Doyle (1824-1883).

February 24, 2014

What love means

Love means to learn to look at yourself The way one looks at distant things

The way one looks at distant things

For you are only one thing among many.

And whoever sees that way heals his heart,

Without knowing it, from various ills.

A bird and a tree say to him: Friend.

Then he wants to use himself and things

So that they stand in the glow of ripeness.

It doesn't matter whether he knows what he serves:

Who serves best doesn't always understand.

- Czeslaw Milosz, 1911 - 2004

("Love," The Collected Poems of Czeslaw Milosz, translated from the Polish by Robert Haas)

A certain day became a presence to me;

A certain day became a presence to me;

and there it was, confronting me - a sky, air, light:

a being. And before it started to descend

from the height of noon, it leaned over

and struck my shoulder as if with

the flat of a sword, granting me

honor and a task. The day's blow

rang out, metallic -- or it was I, a bell awakened,

and what I heard was my whole self

saying and singing what I knew: I can.

- Denise Levertov, 1923 - 1997

(''Variations on a Theme by Rilke," Breathing the Water)

The illustrations above are by Honore Appleton (1879-1951), Richard Doyle (1824-1883), and Walter Crane (1845-1915).

The illustrations above are by Honore Appleton (1879-1951), Richard Doyle (1824-1883), and Walter Crane (1845-1915).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers