Terri Windling's Blog, page 160

July 23, 2014

Solitude à deux

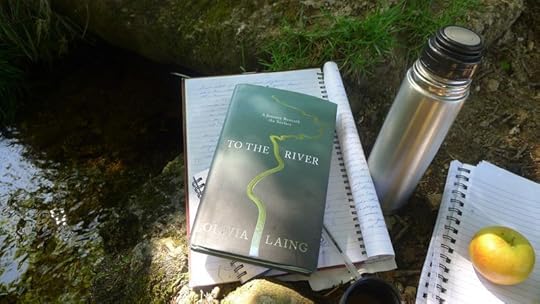

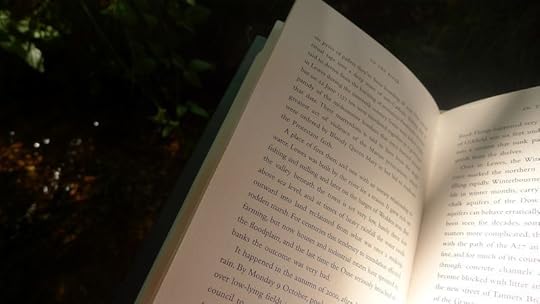

In a fascinating chapter of her book To the River, Olivia Laing reflects on two literary marriages:

"John Bayley and Iris Murdoch were married for 43 years, until her death in 1999, and for most of that time they lived in a sprawling and quite spectacularly filthy house near Oxford, where with a grand disregard for health and safety John dug a swimming pool in the greenhouse and heated it by dangling an electric radiator by its flex."

"John Bayley and Iris Murdoch were married for 43 years, until her death in 1999, and for most of that time they lived in a sprawling and quite spectacularly filthy house near Oxford, where with a grand disregard for health and safety John dug a swimming pool in the greenhouse and heated it by dangling an electric radiator by its flex."

In the latter years of Murdoch's life, when her mind was ravaged by Alzheimer's, she took to "collecting pebbles and scraps of silver foil and asking again and again When are we going? The house -- a different house by now -- is filled in addition to its usual chaos with odd objects she's gathered on her excursions: dried worms, twigs, bits of dirt; the indiscriminate final mutation of a lifetime fondness for inanimate objects....

"This marriage, in which a clever and kindly man takes care of his more brilliant wife, bears a distinct resemblance to that of Leonard and Virginia Woolf, who also lived rather sluttily. Virginia, Leonard once wrote, was a ferocious creator of what he called filth-packets: 'those pockets of old nibs, bits of string, used matches, rusty paper-clips, crumpled envelopes, broken cigarette-holders, etc., which accumulate malignantly  on some people's tables and mantlepieces,' while Leonard himself had a marmoset call Mitz that regularly relieved herself down his back.

on some people's tables and mantlepieces,' while Leonard himself had a marmoset call Mitz that regularly relieved herself down his back.

"Grubbiness aside, the resemblance goes deeper than the superficial similarity of trajectory, for all marriages must end in bereavement of some kind. Instead, it's something about the mechanics of the two relationships, for they each resemble delicate instruments that rely on careful weighing and judicious use of space. Both women were pulled in opposing directions throughout their lives: inward, toward the intense, almost febrile life of the mind; and outward, towards a melange of external love affairs and passions. Despite this both felt their husbands to be the steady centre of their lives, something I think [Martin] Amis had in mind when he wrote that Iris settled, in all senses of the word, for Bayley.

"These two couples nurtured a kind of fertile separateness, a solitude à deux that seems totally at odds with our modern concept of marriage. It is striking how frequently Virginia Woolf and John Bayley in particular write of the pleasure of writing alone in a room, knowing that somewhere else in the house, in their own private sphere, their spouse is also happily at work."

I love the term solitude à deux. I find it deeply pleasurable, too, to be working in the blessed solitude of my studio while music drifts from Howard's cabin, which is just over the hedge from mine. As Rainer Maria Rilke famously wrote in his Letters to a Young Poet (1929):

"The point of marriage is not to create a quick commonality by tearing down all boundaries; on the contrary, a good marriage is one in which each partner appoints the other to be the guardian of his solitude, and thus they show each other the greatest possible trust. A merging of two people is an impossibility, and where it seems to exist, it is a hemming-in, a mutual consent that robs one party or both parties of their fullest freedom and development. But once the realization is accepted that even between the closest people infinite distances exist, a marvelous living side-by-side can grow up for them, if they succeed in loving the expanse between them, which gives them the possibility of always seeing each other as a whole and before an immense sky."

If you're interested in literary/artistic marriages and partnerships in all their permutations, I recommend Significant Others, an anthology of essays on the subject edited by Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron.

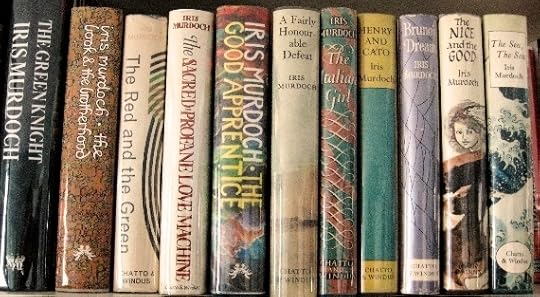

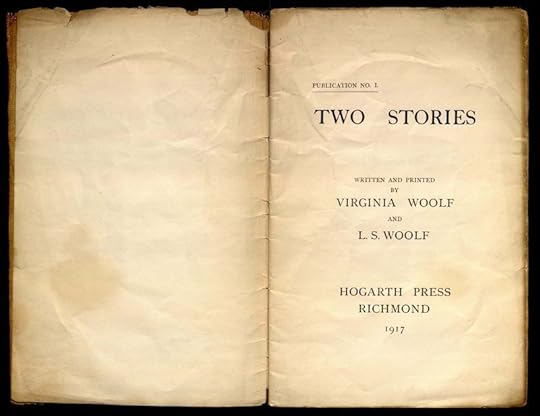

Images above: Books by Iris, the Dame hrself, and two photos of Iris & John at home in Oxfordshire (the first one by Eamonn McCabe). Virginia & Leonard with their dog Pinka in their Tavistock Square house in London (which was destroyed during the Blitz); Virginia's writing shed in the garden of Monk's House (their country place in Sussex); roses in the garden at Monk's House; the first book published by Leonard & Virginia's Hogarth Press; and Leonard & Virginia's earlier London home (where the Hogarth Press began). The last two photos of are Howard's "Little Cabin by the Woods" (his office and theatre/music/puppetry rehearsal space) and my studio next door, reached through an opening in the hedge between them. Solitude à deux.

Images above: Books by Iris, the Dame hrself, and two photos of Iris & John at home in Oxfordshire (the first one by Eamonn McCabe). Virginia & Leonard with their dog Pinka in their Tavistock Square house in London (which was destroyed during the Blitz); Virginia's writing shed in the garden of Monk's House (their country place in Sussex); roses in the garden at Monk's House; the first book published by Leonard & Virginia's Hogarth Press; and Leonard & Virginia's earlier London home (where the Hogarth Press began). The last two photos of are Howard's "Little Cabin by the Woods" (his office and theatre/music/puppetry rehearsal space) and my studio next door, reached through an opening in the hedge between them. Solitude à deux.

July 22, 2014

Nature's gift to the walker

From To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface by Olivia Laing, in which the author walks the River Ouse in Sussex from its source to the sea:

"It was a day of uplift. Everything was rising or poised to rise, the mating dragonflies crashing through the air, the meadow browns clipping sedately by....

"It was a day of uplift. Everything was rising or poised to rise, the mating dragonflies crashing through the air, the meadow browns clipping sedately by....

"I was getting into one of those trances that come from walking far, when the feet and the blood seem to collide and harmonise. Funnily enough, Kenneth Grahame and Virginia Woolf both wrote in praise of these uncanny states, which they thought closely allied to the inspiration writing required. 'Nature's particular gift to the walker,' Grahame explained in a late essay, 'through the semi-mechanical act of walking -- a gift no other form of exercise seems to transmit in the same high degree -- is to set the mind jogging, to make it garrulous, exalted, a little mad maybe -- certainly creative and supra-sensitive, until at last it really seems to be outside you and as it were talking to you, while you are talking back to it.'

"As for Woolf, she wrote dreamily of chattering her books on the crest of the Downs, the words pouring from her as she strode, half-delirious, in the noon-day sun. She compared it to swimming or 'flying through the air; the current of sensations & ideas; & the slow, but fresh change of down, of road, of colour: all this is churned up into a fine sheet of perfect calm happiness. It's true I often painted the brightest of pictures on this sheet: & often talked out loud.' "

Chattering her prose. I do that too. Thank heavens there's only Tilly to hear me as we roam the hills on these bright summer days.

The beautiful painting above is by my good friend and Chagford neighbor Marja Lee Kruyt.

The beautiful painting above is by my good friend and Chagford neighbor Marja Lee Kruyt.

July 21, 2014

In praise of re-reading

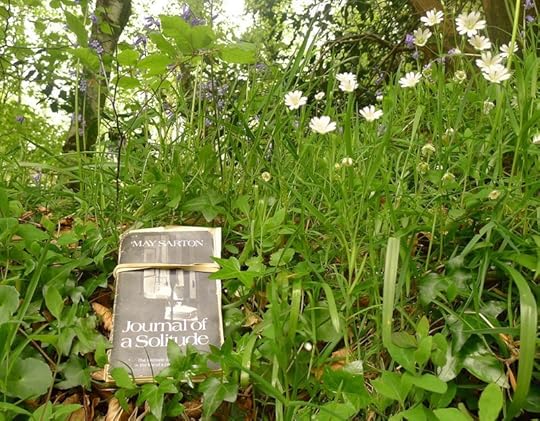

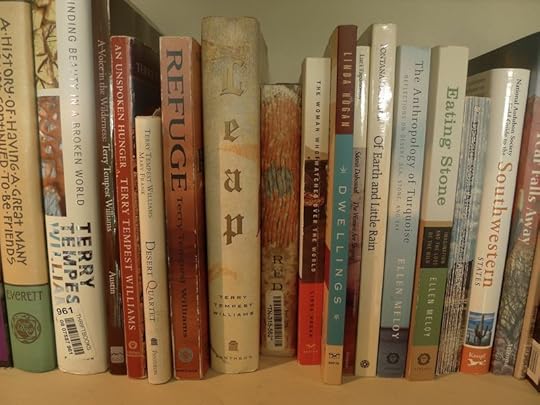

Over the last several months, I've been re-reading my old, dusty copies of memoirs, letters, and essays by women writers and artists -- works that I first encountered in decades past, when I was much younger. Returning to them now, I seem to be reading different books than the ones I remember -- although, of course, it's not the books that have changed with the passing of time but me. Vera Brittain's Testament of Experience and Testament of Friendship, Nancy Hale's The Life in the Studio, Dorothea Tanning's Between Lives, May Sarton's various memoirs, Madeleine L'Engle's Crosswick Journals, essays by Carolyn Heilbrun, Susan Cooper, and Virginia Woolf' -- these were all written by women close to the age I am now, give or take a few years, so my dialogue with them now is a conversation of peers, not age to youth...and there are other differences as well.

In Plant Dreaming Deep, May Sarton recounts the experience of buying and renovating a late-18th century house in a tiny village in rural New Hampshire, where she crafted a life dedicated to poetry, nature's beauty, and solitude. I first read her book in my early 30s when I, too, had just bought my first house: a 16th century cottage in a tiny village in rural England; and I, too, was deep in the work of renovation. My previous decade, like Sarton's, had been rootless and urban; I'd never lived any one place for long; and moving from New York and Boston to Devon was as complicated and impractical it was romantic. I was single then, liberated from a long, confining early relationship; I was back on my feet after two cancer operations; and I was determined to re-build my life as I wanted, now that it was wholly mine again.

What Sarton's book gave me was validation of my decision to settle down and make a real home without marriage or children as my goal. Though life had changed for women between the time Sarton bought her first house in 1955 and I bought mine in 1992, it hadn't changed entirely. Single women were still quietly pitied for our presumed failure to find a mate, even those of us with rich romantic lives who simply enjoyed living alone. (I should mention that during the winter months I shared a house in the Arizona desert with a friend, so although I valued my independence, I was hardly a hermit.) A male colleague fretted that I was in danger of turning myself into Virginia Woolf, by which he meant an accomplished but dried-up old spinster -- oblivious both to my complicated love-life and the fact that Woolf had a long, close marriage.

Plant Dreaming Deep chronicles the reclamation of Sarton's farmhouse, the planting of its extensive garden, and the slow adjustment of an intensely intellectual woman to the physical rhythms of rural life. The book is a celebration of the bittersweet virtues of solitude, independence, and self-reliance -- and yet Sarton, too, was not a hermit. Her life was amply stocked with friendship, romance, travel, adventure, and the international web of connection arising from a long literary career. She spent time with lovers and friends in Boston, she taught, she travelled around the country giving readings ... but she did her best work in solitude, and work was her priority.

A woman living alone and unmarried by choice, privileging her writing over other social bonds, was rare enough when Plant Dreaming Deep was published in 1968 that it caused something of a stir. "Sarton chose the way of solitude with all its costs," wrote Carolyn Heilbrun (in an essay published in 1982), "and heartened others with the news that this adventure, this terrible daring, might be endured."

This was a message that many in Sarton's generation hungered for and the book was a popular success, appealing particularly to women who had given up their own work after marriage and children and who had little solitude themselves. They romanticized the life she led, imagining a tranquil idyll of poetry and music and flowers from the garden, not the hard labor and professional ups and downs of life as a working writer. Sarton herself came to feel that she'd painted too rosy a picture of her sojourn in the country -- and so her next memoir, The Journal of Solitude, aimed to set the record straight. In this book, she recorded her doubts, her creative struggles, her professional frustrations, her poignant loneliness. The woman who emerges in these pages is prickly, moody, often exasperating...and thoroughly human.

When I first read The Journal of Solitude, I appreciated its craft and honesty -- in many ways it's a better book than the first -- but I was, I remember, dismayed by the strain of bitterness that runs all through it. I could not help but wonder: would the independence I deeply craved leave me this bitter at Sarton's age? As I finished the book, I felt obscurely let down, for it seemed to suggest that the price for a work-focused life was high indeed.

Returning to Sarton two decades later, however, I see what I somehow failed to see before: The Journal of Solitude is not a book about the loneliness of the single life, it's a book about depression. This fact is so glaringly obvious that it's hard to fathom how I missed it back then...but at that time I didn't yet know the signs of long-term, clinical depression, whereas now I know them all too well due to a close family member and friends who have suffered beneath its weight.

And with this knowledge, I find myself reading an entirely different book this time, with different insights, observations, explications, and resonances. Instead of dismayingly bitter, Sarton comes across as sharp and irascible, yes, but also honest, tenacious, and brave, pushing through the grey clouds to return to the light not once but again and again. The pain that the poet is never quite rid of no longer seems like solitude's dark twin; it's the pain of a mental state that makes her solitude necessary, and healing.

Likewise, Madeleine L'Engle's four Crosswick Journals speak to me now as they never did before, written in a language of age and experience in which I've become more fluent. When I read the first three books back in the mid 1980s (the fourth was not yet published then), I found the author's life to be interesting but also alien: her glamorous parents, her international upbringing, her marriage to a Broadway actor and soap opera star, her children, her dogs, her homes in New York City and rural Connecticut...it was all so removed from the life I led as a struggling young writer/editor that we inhabited different world altogether -- even though we lived within blocks of each other on Manhattan's Upper West Side. I read L'Engle's journals with a certain detachment, for other than our shared taste for fantastic fiction we seemed to have very little in common. I underlined a few choice passages about writing, then put the books back on the shelves. I kept them, but I had no urge to re-read them until this year.

I opened the first volume, A Circle of Quiet, expecting to re-read it with the same mixture of interest and distance, the same wide gulf between the author's focus (marriage, children, church) and mine. But L'Engle had changed in the intervening years; the very words printed on the page had changed; and yes, I know that is quite impossible but so it actually seemed to me, for now her books had much to say that I was finally ready to hear. A quarter of a century has passed; I am roughly the age that she was then; and, surprisingly enough, her life and mine are not so far very apart now. I, too, have an actor husband, a family, a house in the country, a shelf full of published books...all of it on a much smaller scale than L'Engle's, yet close enough to share similar concerns about juggling conflicting commitments to family, community, and creative work. My life took an unexpected turn when I married my husband and became a parent; now I come to these books from a whole new direction, through a door I could not even see, much less pass through, when I first read them. In this re-reading, it is only the third volume (a meditation on Christianity, and how L'Engle's faith intersects with her work as a writer) that I still read with my early detachment...and who knows? In another quarter century a door might open into that one too.

I am speaking here of books that reward re-visiting, revealing new aspects of themselves each time you open them: Vera Brittain's fascinating, heart-rending memoirs; Virginia Woolf's brilliant diaries; Terry Tempest William's gorgeous books, falling somewhere between memoir and nature writing. (If I expanded this essay into fiction, then authors ranging from Jane Austen to Ursula Le Guin would certainly be mentioned here.)

Other books, however, remain stuck in time -- eloquent and profound at one stage of life, but stubbornly mute when you try to return; the door that stood open for the person you were has slammed shut for the person you are. Anaïs Nin's diaries fall into that category for me -- so influential in my late 20s that it's no overstatement to say I would not be the woman I am without them, and yet I can no longer read Nin with that youthful hunger and uncritical pleasure. This doesn't diminish her work for me; the diaries remain a classic of the form, and they still have a place of honor on my shelves. But some books -- and it's different books for every reader -- seem to belong to a certain age, a certain stage of one's development. Re-reading them is an exercise in nostalgia, rather than one of discovery, and although that has its pleasures too, it is a melancholy kind of pleasure, tinged with the sepia of loss. Every so often, however, I take Nin's diaries down from the shelves again, breathing in the scent of the young woman I once was. Perhaps one day a new door back into those books will stand ajar.

"I, too, feel the need to reread the books I have already read," remarks a character in Italo Calvino's great novel If On a Winter's Night a Traveler, "but at every rereading, I seem to be reading a new book, for the first time. Is it I who keep changing and seeing new things of which I was not previously aware? Or is reading a construction that assumes form, assembling a great number of variables, and therefore something that cannot be repeated twice according to the same pattern?"

I'd say that it's both those things, at different times, for different books, for different readers.

Rebecca Mead's The Road to Middlemarch: My Life With George Eliot is an especially lovely tribute to the fine art of re-reading. "There are books," she writes, "that seem to comprehend us just as much as we understand them, or even more. There are books that grow with the reader as the reader grows, like a graft to a tree."

Patricia Meyer Spacks notes that the pleasure of re-visiting our favorite books is one of mingled familiary and surprise. "By definition, rereading reacquaints us with the familiar. It does so, often, by defamiliarizing. The book we thought we knew challenges us to incorporate fresh elements in our understanding. The book we loved in childhood provides delights we never anticipated. We thought we already knew what it was about, but now it tells us that it is about something else. As our memories inform our understanding, that understanding changes. We who love rereading love it for its surprises as well as for its stability." (I recommend her book On Rereading if you'd like to explore this subject further.)

"We do not enjoy a story fully at the first reading," C.S. Lewis states provocatively in his essay "On Stories" (1947). "Not till the curiosity, the sheer narrative lust, has been given its sop and laid asleep, are we at leisure to savour the real beauties. Til then, it is like wasting great wine on a ravenous natural thirst which merely wants cold wetness. The children understand this well when they ask for the same story over and over again, and in the same words."

Read it again, our kids demand when we close their favorite storybooks. Read it again. And again. And again. One reading is simply not enough.

As adults, many of us have a book (or books) that we've read not once but countless times ... and I suspect you can learn quite a lot about a person by finding out what it is. Working in the fantasy field, it's assumed that I'm a re-reader of The Lord of the Rings, but I hereby confess that I've read Professor Tolkien's great epic exactly twice: first in my teens and again in my twenties when I was commissioned to write about it. The book I've re-read so often that I've long lost count is Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice -- which I didn't even particularly like when I first encountered it in youth, but which has dazzled me with its clarity, depth, and wicked humor in every reading since. Re-reading the novel at a slightly older age was the key that unlocked its treasures.

So let us praise the distinctive pleasures of re-reading: that particular shiver of anticipation as you sink into a beloved, familiar text; the surprise and wonder when a book that had told one tale now turns and tells another; the thrill when a book long closed reveals a new door with which to enter. In our tech-obsessed, speed-obsessed, throw-away culture let us be truly subversive and praise instead the virtues of a long and slow relationship with a text unfolding over many, many years. In an age that prizes novelty, irony, and youth, let us praise familiarity, passion, and knowledge accrued through the passage of time. As we age, as we change, as our lives change around us, we bring different version of ourselves to each encounter with our most cherished texts. Some books grow better, others wither and fade away, but they never stay static.

"No reader can fail to agree that the number of books she needs to read far exceeds her capacities," writes Patricia Meyer Spacks, "but when the passion for rereading kicks in, the faint guilt that therefore attends the indulgence only serves to intensify its sweetness.”

Do you feel guilty for re-reading? I never have -- just frustrated that this one short life is not nearly long enough for all the books that I want to read and re-read. Revisiting books over years, over decades, is a complex, multi-layered experience that the excitement of first-time reading can never match, although it has its distinctive pleasures too. Re-reading is a different art than reading, but certainly not a lesser one.

So today, let us praise re-reading, since reading itself has less need of champions. Let us praise old books dog-eared, creased, cracked, faded and marked through years of handling. New books are fine but give me old ones too, underlined, coffee-stained, containing the ghosts of the woman I was and the woman I will be, the next time I read them.

Let us praise re-reading, which gets richer and deeper with age. Take heart, young readers. The best is still to come.

In addition to the books mentioned above, I recommend Lisa Levy's essay, "The Pleasures and Perils of Rereading"; Anne Fadiman's charming anthology, Rereadings: 17 Writers Revisit the Books They Love; and Francis Spufford's memoir of a reading life, The Child That Books Built.

July 20, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Thank you all for your kind, kind messages while I've been gone, which have touched my heart more than words can express. The "Life Stuff" that has been dominating my time is not quite over yet, but I'm going to try to post again, at least as often as I'm able to.

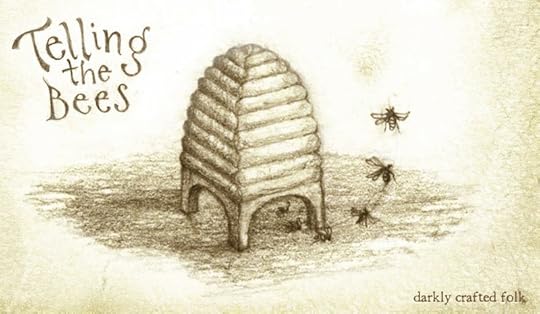

The songs today are for the bumblebees that gave our house its name, Bumblehill. And for bee lovers Amal El-Mohtar (author of The Honey Month) and Chagford fabric artist Angharad Barlow (creator of Sustainable Stylings and Atelier Bee).

Above: "Save the Bees" by the brilliant Anglo-Scots folk trio Lau, filmed in 2012.

Below: "The Hum" by the Yorkshire folk duo O'Hooley & Tidow, filmed earlier this year in Leeds.

Above: "Beekeeper" by singer-songwriter Aoife O'Donavan, from Boston, performing solo at McCabe's in Santa Montica last December.

Below: "Beeswing," performed by the Irish band Caladh Nua in in Castle Gurteen, Kilsheelan, Co. Tipperary, 2013. The song was written by the great Richard Thompson.

In the last video today, Andy Letcher (another Chagford friend) explains the inspiration behind his band Telling the Bees. I highly recommend both of the band's CDs (with cover art by Rima Staines for an added bonus). Their lovely song "Telling the Bees" is not online, but you can listen to an equally lovely song, "Blackbird" here.

"Telling the bees" is an old English folk custom -- which many still practice today -- in which bees are kept informed of all significant events in family and village life.

Amal with Tilly at the top of Nattadon Hill a while back. They've been good friends since Tilly was a pup. "We have, " Amal says, "each of us, a story that is uniquely ours -- a narrative arc that we can walk with purpose once we figure out what it is." (Tapping the Long Tale)

Amal with Tilly at the top of Nattadon Hill a while back. They've been good friends since Tilly was a pup. "We have, " Amal says, "each of us, a story that is uniquely ours -- a narrative arc that we can walk with purpose once we figure out what it is." (Tapping the Long Tale)

Angharad in her beautiful bee coat. "The earth bee," she says, "enables the energy, spirit and ideas to exit the cloth, so that nothing can get trapped and the magic can flow in and around the wearer.

Angharad in her beautiful bee coat. "The earth bee," she says, "enables the energy, spirit and ideas to exit the cloth, so that nothing can get trapped and the magic can flow in and around the wearer.

July 17, 2014

Guest Post: Mythic Theatre in Devon

Parzival

at Sharpham House

reviewed by Howard Gayton

On arrival at Sharpham, the marshals help you to park and find your way to the "holding field," with its beautiful views across the River Dart. As the audience sits admiring the landscape, a faint sound of drumming comes from the woods below; not awful ‘"let’s bang on a djembe" drumming, but rhythmical, pulsing, and fun. There is something interesting and enticing happening down there in the trees. Immediately you know that real care and thought has gone into this promenade performance: you will be in safe hands during a journey both physical and metaphysical into the forest and on the quest for the Grail.

For promenade performance to succeed, it needs a skillful guide. In this show, the task falls to the artful storyteller, Martin Shaw. Throughout the evening, he entertains, guides, informs, and cajoles the audience -- throwing in funny, throw-away contemporary references every now and then, while also drawing pertinent parallels between the world of myth (in which the audience finds itself) and our own times, our own lives.

The flow of the show -- both physically, in the movement from the forest to the court and then to the castle, and in the narrative -- is superbly handled. This is achieved by a combination of well-executed elements: the stunning grounds of Sharpham used in perfect combination with the narrative; the masked ushers and the ever-present story-teller guiding us on; musicians and drummers keeping us connected to the play as we move through the trees; and skillful stage management moving actors and props unobtrusively from scene to scene.

Sharpham itself provides magnificent spaces for the performance, with just the right addition of scenography and lighting where needed. These are never intrusive; and, as with all the elements of this production, handled with great sensitivity to both the story and the land.

Each scene is played out in a different part of the estate by a wonderful ensemble cast who are clearly enjoying themselves. The acting is good: physical, funny, moving, and committed. Lines are delivered well, and are audible. (Too many outdoor productions suffer from inaudible dialogue.) There are lovely touches of characterization and well delivered humour. My own speciality is mask theatre, so I feel justified in singling out one particularly fine actor in this regard. Mask work is woefully bad in many productions, but Helen Aldrich inhabited her mask brilliantly, with the right physicality to support it. This adds yet another layer of myth and magic to an already magical show.

As well as the show's professional cast there is also a company of community members who play the masked guides. Dressed in black with blue sashes, they subtly move the audience forward and create temporary performance areas. They also play in some scenes themselves -- which they do with gusto and, as with the main cast, a good sense of ensemble.

The production's music is just right: from the incredible drumming that greets the audience in the first forest glade to the incidental music -- subtle, humorous, and evocative by turns -- played on a variety of strange looking instruments.

It is a precious thing to find theatre that entertains and transports; that, for a few hours, brings you into a mythical world. Theatre strives to make the intangible mystery of the human condition tangible, if only for a brief moment. Parzival achieves this ... and then, as with all good theatre, the ephemeral nature of the form asserts itself. The glimpse of the "intangible made tangible" slips once again beyond our grasp ... like the Grail of the story.

Directed by Matthew (Harry) Burton, Parzival shows the powerful nature of what theatre can and should be, when all of its elements -- story, performance, use of space, lighting, music and production -- work seamlessly together. It's running at Sharpham House until Sunday, July 20th. If you like theatre, if you like myth, and particularly if you like the combination of the two, then hurry to get one of the last tickets for this inspiring, thought-provoking show.

June 29, 2014

Dear readers,

Myth & Moor is now officially on a tem...

Dear readers,

Myth & Moor is now officially on a temporary hiatus. I'll be back online as soon as I can be. Many thanks to you all for your supportive messages, and for hanging in there with me.

''Keeping your body healthy is an expression of gratitude to the whole cosmos - the trees, the clouds, everything.'' - Thích Nhất Hạnh (Touching Peace)

Art above: "In the Forest of Peace" by Kinuko Y. Craft, and Tilly in our own Forest of Peace.

Dear readers....

Myth & Moor is now officially on a temporary hiatus. I'll be back online as soon as I can be. Many thanks to you all for your supportive messages, and for hanging in there with me.

''Keeping your body healthy is an expression of gratitude to the whole cosmos - the trees, the clouds, everything.'' - Thích Nhất Hạnh (Touching Peace)

Art above: "In the Forest of Peace" by Kinuko Y. Craft, and Tilly in our own Forest of Peace.

June 27, 2014

The Dog's Tale

While my Person is distracted by matters I don't understand, I've made a wolf den beneath this old bench....

Shhhh! Don't tell! I'm not actually supposed to dig up the grass and the flowers.

Just a little dirt. Just a little grass. A few bulbs. No one will even notice.

June 26, 2014

Climbing

I'm climbing a mountain over the next few days regarding the "Big Life Stuff" I'm facing, and won't be back until next week.

There are mornings when Tilly's steady presence is what gets me up, outside, and keeps me going.

Dog teach us how to live in the present moment instead of the landscape of our worries -- with our eyes and our hearts wide open, our souls expansive, our bodies soft and supple. They show us how to keep on climbing while still "creating the environment" for joy.

June 24, 2014

Rock and water

"If we are not willing to fail, we will never accomplish anything. All creative acts involve the risk of failure. Marriage is a terrible risk. So is having children. So is giving a performance in the theatre, or the writing of a book. Whenever something is completed successfully, we must move on, and that is again to risk failure." - Madeleine L'Engle (Two-Part Invention)

"It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously that you might has well not have lived at all, in which case you have failed by default." - J. K. Rowling (from her TED talk on failure)

"Failure is unimportant. It takes courage to make a fool of yourself." - Charlie Chaplin

"I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it." - Pablo Picasso

Some days feel like failures. Other days I inch forward. But whether toad day or gold day, I keep showing up; I give what I have, sometimes much, sometimes little. The rocks lend their strength, and the water, its quiet persistence.

"Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” - Samuel Beckett

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers