Anne Lyle's Blog, page 7

October 2, 2013

Unexpected Journeys: an epic fantasy anthology

I’ve been sitting on (and occasionally hinting at) this news for weeks now, and at last I can spill the beans: I have a short story in an upcoming anthology of epic fantasy, edited by Juliet E McKenna and published by the British Fantasy Society. W00t!

Unexpected Journeys has an awesome table of contents, with contributors including Kate Elliott, Gail Z Martin, Adrian Tchaikovsky and Stephen Deas. The anthology will be launched on 31st October at the World Fantasy Convention in Brighton, and will be given away free to all current BFS members.

My own story is titled A Thief in the Night, and is set in the world I’ve been developing for a new series of novels, but several centuries earlier. It’s given me a chance to play with a really cool idea that didn’t quite fit into the novel series, and also stretched my short-story-writing skills (this is only the second short story I’ve had published, as I so seldom write them).

Please note: you will not be able to buy the anthology in shops or online; it’s a BFS membership exclusive. The electronic rights will revert to me in early 2014, however, at which point I will decide when/how to republish it.

Never the same river twice

We’re always told that if we want to write well, we should read widely and voraciously, and I totally agree with that—if you haven’t absorbed the rhythms of good prose and are unfamiliar with the conventions of your genre, the chances of you producing something awesome are greatly reduced (though not impossible). I certainly devoured books when I was younger and had more free time on my hands, but since I got published I find myself juggling two careers (author and web developer) and having to carve out reading time whenever I can find the headspace. Because it’s not just time that I require in order to enjoy a book nowadays; I find it very hard to focus on other people’s stories when I’m working on a draft because my own is constantly clamouring for attention.

Still, I love reading and I do want to keep up with what my peers are doing in fantasy, so I read as much as I can during lulls in my writing schedule. This summer has been a good time in that respect: the final revised version of The Prince of Lies was handed over in May, and though I was working on developing a new project, I was content to let that simmer in the background during the week and only give it my focus at weekends. Hence I’ve been catching up with a bunch of books that have been sitting in my TBR queue for a while (about 5 years in the case of Red Seas Under Red Skies!).

Given my time constraints, just reading a new book is a luxury, never mind re-reading—but when Marc Aplin of Fantasy Faction announced he was doing a read-along of both of Scott Lynch’s books in the run-up to the release of The Republic of Thieves, I couldn’t resist joining in (you can join in too, on the Gollancz blog). I only had time to re-read The Lies of Locke Lamora, and in any case Red Seas Under Red Skies was still fresh in my mind, but the experience was something of an eye-opener.

When I first read LoLL back in 2007, I gave it a mere 3 stars on GoodReads, mainly because of a torture scene that really freaked me out and spoiled the experience of the book for me (I had gruesome nightmares the night after reading it). The re-read benefited from the fact that I was able to skip the scene in question, but also I was able to sit back and enjoy the ride much better than on the first reading. The trouble with being a voracious reader is that one tends to race through a book just to find out what happened, and though you enjoy good prose as much as the next person, you may miss the subtler aspects of the story. The biggest change, though, was one I hadn’t really thought about: I am not the person who read this book back in 2007.

Back then I was an unpublished writer with a mere single novel draft under my belt (and that a rough, half-revised mess of a thing), with all the cockiness of someone who thinks they know what they’re doing but still lacks experience (see Dunning-Kruger effect). Also, I’d read extensively in my younger days but I really wasn’t up to speed on the kind of book being published in the fantasy genre in the twenty-first century. Hence The Lies of Locke Lamora came as a shock to the system: visceral, sweary and populated by some of the nastiest villains I’d come across in a long time. I liked it, but it made me too uncomfortable to love it.

By the time of my re-read I had two novels out and a third in production. I knew just how damned hard it is to put together 130k+ words of good prose—and to repeat the act to order. I’d also read a few other so-called gritty fantasies, such as Joe Abercrombie’s First Law trilogy, and The Steel Remains by Richard Morgan. I guess you’d say I was desensitised, but in a good way. As I mentioned, I still skipped the torture scene, but the rest didn’t bother me nearly as much—and as my readers know, I’m not afraid to put a few four-letter words in my own prose these days!

I was thus able to focus more squarely on the book’s other qualities. Armed with my knowledge of how to put a story together, I was able to appreciate Lynch’s back-and-forth narrative instead of finding it a distraction, and I revelled in the little details (like the squid-and-tomato soup served during a combat display pitting prisoners against a deadly tentacled sea-monster). All in all it left me stunned and awed that this was a debut from a relatively young writer (he was 28 when it was published), and I immediately upped my GoodReads rating to a 5

Finding time to read is still an issue for me—the next three or four months are going to find me slaving over the first draft of my new novel—but I do hope I can fit in a re-read of another good book next year. If only my TBR pile would stop growing…

September 25, 2013

Generating words for your conlang

One of the most labour-intensive stages of creating a conlang (constructed language) is generating the masses of words required, and also of ensuring you have enough distinct words that use the full range of options that you designed into the language. Thankfully it’s a trivial task to do this with a computer program, and being a developer myself I’ve written a simple script that can be used to generate an “instant dictionary”.

Now obviously you’re not constrained by the output; if you see a word that doesn’t feel right for the assigned meaning, then of course you’re free to swap it for something else. Use your auto-generated dictionary as a jumping-off point to get you going, rather than a shackle for your creativity!

The technical stuff

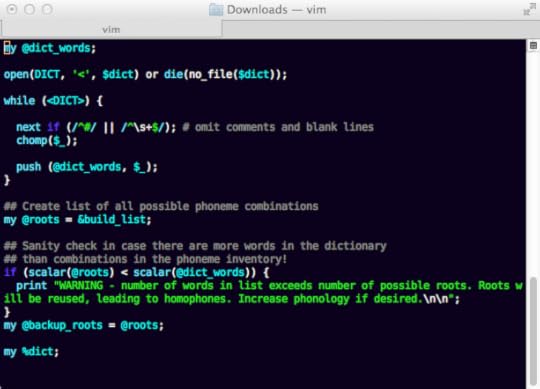

Perl script in OSX Terminal

Perl script in OSX TerminalNice as it would be to offer you a standalone program, I’m not qualified to do that. Instead, I’ll show you how to use a popular programming language called Perl to run my code. Perl was designed to be good at handling strings of characters, so it’s the perfect language for conlanging. Don’t worry, you won’t have to write any code per se, just the file that describes your conlang.

If you’re using a Mac, you can skip the rest of this paragraph, as Perl is provided as part of the OSX operating system (ditto with Linux, but if you’re a Linux geek you probably already know about Perl!). If you’re a Windows user, you can get a free installation bundle from ActiveState; I originally learnt Perl when I was still on Windows. If you go this route, I suggest selecting the 5.14.x package, as I haven’t had the opportunity to try my code on version 5.16.x yet.

You’ll also need a program that can create and edit plain text files. In Windows, you could use Notepad or Wordpad, but I recommend the free text editor Notepad++ as it will be better at handling the files I’ve written in OSX (Windows and Unix use different non-printing characters to denote line endings). For Mac users, the built-in TextEdit program will do fine as long as you make sure to save new files as plain text, not .rtf, or you might like to try the free text editor TextWrangler.

Both Notepad++ and TextWrangler have syntax highlighting, meaning they colour-code the text according to its meaning within the format/programming language being used. This doesn’t make much difference with text files, but if you start poking around in the Perl script, it’s very helpful for distinguishing blocks of code from comments.

Please note that I can’t offer technical support on installing and using these common tools; there are masses of resources online, so I recommend you resort to Google if you have any problems.

You’ll need to run the script in a terminal window; rather than try and explain that here, I’ve linked to some handy online tutorials:

Windows command prompt tutorial

OSX terminal tutorial (NB. the built-in Terminal program, found in Applications/Utilities, is more than capable of running this script, so you don’t need to install iterm)

Finally you’ll need to download the zip file containing my Perl script and some sample input files.

instant_dictionary.zip (9Kb)

Preparing your input

My dictionary script takes two input files. One is a simple list of English words that you’d like to “translate” into your conlang. I’ve provided two sample lists, based on various “universal word root” lists that I’ve encountered over the years. One is fairly short—only 200-odd words, mostly verbs, nouns and adjectives—whereas the other is over a thousand items long and covers a wider range of concepts. It’s a good idea to edit them to suit your conlang’s culture; for example I omitted words like “husband”, “wife” and “marriage” from my Vinlandic dictionary as skraylings don’t live together after mating.

The other input file you need is one that defines the sound patterns in your language; it’s the one named ‘example.conf’ in the download. This requires a bit more explanation!

The lines starting # are comments, meaning that they are ignored by the Perl script, so you can use them to remind yourself what each part of this “sound configuration” file is doing.

First we define our pattern of sounds within a word – see last week’s post on how to design a phonology for your conlang. Each capital letter in the pattern represents a list of sounds that we’ll define later in the file. The letters can be anything you want as long as they’re unique to each sound group; I generally use C and V to represent the full range of consonants and vowels respectively, and other letters to represent subsets of sounds.

Here, I’ve decided that the pattern is a consonant, a vowel, a “final” consonant, and a short vowel. Note that there has to be a space between each letter.

# Pattern of phonemes in root

Name=Pattern

C V F S

Next we have to define each sound group. For each one, you need a line Name=X, where X corresponds to one of the letters in your pattern, then immediately below that you list the sounds, again separated by a space.

In this very simple example, all sounds have equal frequency in the language. For a more naturalistic result you might want to increase the frequency of some sounds and make others rarer. This is simple to do; just include multiple examples of the common sounds in your list, and include rare ones only once. (This will also potentially introduce homophones into your conlang, which is a good thing if you’re aiming for naturalism.)

Another refinement you can make is to allow an element to be optional. To do this, include a hyphen as one of your possible “sounds”; the script will strip it out when it prints the dictionary. As with other sounds, you can vary the probability by altering the frequency of hyphens in your list.

Note also that the definitions don’t have to be in the same order as the elements in your pattern, and that you only need to define each group once.

# Consonants

Name=C

p t k b d g

m n l r s z

h w y -

Name=F

p t k b d g

m n l r s z

# Vowels

Name=V

a e i o u

aa ei ii ai ao ou

Name=S

a e i

Create your own file; if you name it after your conlang (e.g. vinlandic.conf), that name will be used in the header of the output file. Make sure you keep all the files in the same directory as the script.

Running the script

Now comes the moment of truth!

In your terminal window, navigate to the folder that contains the downloaded files, and type:

perl instadict.pl -s example.conf -d short_wordlist.txt

Obviously you can substitute the name of your sound file and use the longer word list if you prefer. The script will run, and within moments you should have your output file. Then in your Windows File Manager (Finder in OSX), look in the conlang directory for an HTML file, then double-click on it to open in a browser window. Voilà! Instant dictionary

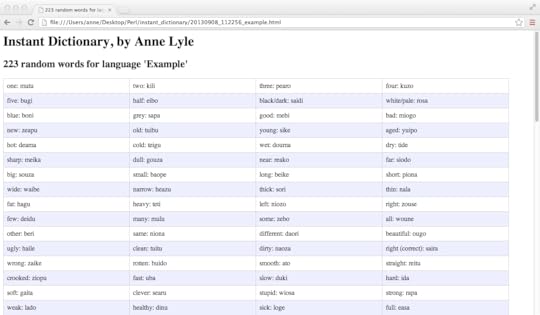

Screenshot of sample output using the provided input files

Screenshot of sample output using the provided input filesIf you would prefer a simple text file listing the results, append the flag –txt to your command, thus:

perl instadict.pl -s example.conf -d short_wordlist.txt --txt

Either way, if you’re not happy with the results, you can run the script again. By default the script includes a timestamp in the output file name, so it creates a new file each time.

That’s really all there is to it. I hope you find this script useful; do let me know how you get on!

#SFWApro

September 20, 2013

I&E follow-along: Finding the plot

This last couple of weeks I haven’t made a lot of progress on I&E because I’ve been catching up on promo work for The Prince of Lies: blog posts, interviews, etc. On the other hand the WiP has never been far from my mind, since my planning time is rapidly running out!

Because of all the changes I’ve made in the past few weeks, I now find myself with a bunch of characters in search of a plot. I have personal arcs for the protagonist and another major character, and I have the beginnings of a wider conflict – but I currently have little idea of where that’s going or who’s behind it, which is very frustrating. I think I need to sit down this weekend and use whatever tools Holly has given us on HtTS (Dot & Line, etc) to ferret out the main conflict and resultant plot.

On the plus side, I have a better idea of how the series is going to work structurally, and I even have a possible title and fledgling concept for a third book. Now if only I can rein my Muse in and focus on the WiP…

September 17, 2013

Conlanging 101

Last week I gave a very brief history of language construction and mentioned some well-known examples from fantasy, such as Sindarin and Dothraki. If you’ve been inspired by any of these books or TV shows to create a language of your own, read on! Note that I shall be focusing on creating languages for use in fiction; whilst conlanging for its own sake is a great hobby, it can be easy to get carried away and create something too arcane for your readers to cope with.

Bear in mind also that language creation is a vast topic that can’t be covered in a single blog post; however I shall link to resources that will help you to take your first steps in this fascinating hobby.

What’s the purpose of your language?

“What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Before creating your language, it’s best to think a little about what you want to achieve. Maybe you just want to come up with a consistent set of names for your novel’s characters and places, or maybe you want a language you can use within the story itself, to add the kind of depth that Tolkien achieved with Sindarin. The former is obviously a lot quicker and easier than the latter since you basically just need some nouns and adjectives, not the entire grammar!

Even if you do go the full nine yards, bear in mind that less is more. Many readers of The Lord of the Rings skip over Tolkien’s songs and poems (whether in English or Elvish); large chunks of incomprehensible text are rather daunting. When editing the later drafts of The Alchemist of Souls I cut a skrayling chant from the scene where the ambassador arrives in London, mostly to spare my audiobook narrator the hard and frankly rather pointless work! However I did retain a few full sentences here and there; just enough to give a feel for the skrayling languages without overwhelming the reader.

In addition to names of people and places, you might want to create a few nouns and phrases for things that exist in your invented world that have no English (or maybe Earth) equivalent. One word frequently encountered in the Night’s Masque books is amayi, an Aiyaluran word that means something akin to ‘soulmate’, though with additional shades of meaning that the English word lacks.

English is weird

If you’re a native speaker of English, you’re no doubt aware that we have some pretty arcane spelling rules, but you probably don’t realise just how atypical English is of the world’s languages. Our word order (subject followed by verb followed by object, e.g. I like cats) maybe fairly common, but the way we construct our verbs, with few markers for number, person or tense, is not. Also, English has some sounds that are relatively uncommon in other European languages (‘th’ is a particular problem for many non-native speakers), and is very fond of complex clusters of consonants. For example Japanese often inserts vowels into borrowed English words, to break them up into something closer to its own consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel pattern.

Learning other languages, especially non-Indo-European languages, will help give you a much wider perspective, but learning a language is time-consuming. An easy shortcut is to read overviews that describe the main features of a language without attempting to teach it to you. There are some good books on the subject—e.g. An Introduction to the Languages of the World by Anatole V Lyovin, which includes brief sketches of such diverse languages as Russian, Mandarin Chinese, Arabic, Hawaiian and Yu’pik Eskimo—and of course most of the world’s languages have a Wikipedia page describing their main features.

Designing a phonology

The full list of sounds that a human vocal tract can produce and that are used in extant languages is vast, and once you discover them it can be tempting to throw them all into your conlang. However bear in mind that if you’re creating a language to use in a book, your readers need to be able to make a reasonable stab at pronouncing the names in their heads, otherwise they will be constantly stumbling over the text.

Rather than adding new sounds it is often easier to omit a few; for example my skrayling language Vinlandic lacks labial sounds (p, b, and m) because the males like to be able to show their fangs when speaking. Also, unless you’re parodying pulp-era SFF, avoid weird clusters of consonants and needless accents/punctuation. Both will make your conlang look amateurish.

Words, words, words

Once you have your phonology you should come up with some standard morpheme templates (see below), so that you can start generating words, either by “hand” or using a computer script to generate lists of valid combinations (a topic I will cover next week).

A morpheme template is a pattern into which you slot sounds. For example:

CVCV(n)

where C = consonant, V = vowel, and (n) is an optional letter ‘n’. Using this template, example words in your languages might be leron, situ, tana, and so on. This simple process will ensure that your language has a consistency that will help to make it feel realistic. (I would, however, advise against using this exact pattern, as it’s become a cliché in SFF. It even has its own page!)

Grammar

Even if you only want to create names, you will benefit from a few basic rules of grammar for your language that will help to make it consistent. For example, do adjectives precede nouns, as in English, or do they come afterwards, as in French? (OK, not all French adjectives go after nouns; natural languages are often highly irregular!) What are the common ways to turn verbs and nouns into other nouns, as in English “walk” -> “walker”, “art” -> “artist”? As with the sound system your readers will pick up on these simple patterns, if only on a subconscious level, because our brains are naturally attuned to decoding language.

If you want to go beyond names, you’ll need to know how to fit words together into sentences. How much development you do is really up to you, but be warned—once you get into this stuff, it can be really addictive! It took me several attempts to come up with suitable languages for the skraylings in my Night’s Masque trilogy; the early iterations used all manner of arcane syntax, but I ended up throwing out a lot of it and starting again with simpler rules. Since I was running out of time by this point, I also only created the bare minimum needed for the books, instead of trying to complete a working grammar and vocabulary.

Even if you don’t create an entire language behind the scenes, it’s possible to come up with something that sounds authentic. The greatest compliment you can receive as a conlanger is for someone to ask “What language did you use in your book?” (with the implication that it was a real Earth language), as happened to me at a reading of Chapter 1 of The Merchant of Dreams at FantasyCon 2012. I admit I had rehearsed the scene thoroughly until I could speak the lines of dialogue as fluently as the rest of the text, but it was still very pleasing to hear.

Documenting your work

An important point that is rarely touched upon in conlang instructions is the importance of keeping accurate records. Writing a novel is a time-consuming and complex task taking months or years, and by the time you get to final edits it’s easy to forget the language rules that you came up with back when you were worldbuilding. And what if you want to write a series? Readers expect consistency, and if your books become popular you can be sure that a small minority of fans will start analysing your conlang!

My advice is:

Learn how to describe your language accurately and gloss entire sentences (i.e. give a written breakdown of the words in use) – see my description of Aiyalura for examples

Compile two-way dictionaries, e.g. English->Vinlandic and Vinlandic->English, to make your life easier

Back up any electronic documents, and ideally print them out as well

Conversely, if you do a lot of conlang work on paper, consider making scans of the finished documents and store them somewhere online

Learning Resources

I’ve really only been able to skim the surface in this article. For much more detail on how to put a language together, see the following:

Create a Language Clinic, by Holly Lisle (ebook) – aimed at complete beginners, this workbook is ideal if all you want to create is a naming language. It also has a great chapter on the weirdness of English!

The Language Construction Kit (web version; also a paperback book) – a great introduction to conlanging, suitable for beginners but going into some detail on linguistics

The Language Creation Society – provides links to masses of online resources for conlangers. Paid membership includes free web hosting for your conlang materials and related projects

Next week I’ll be concluding this brief series of posts with a look at a Perl script I’ve written to help with vocabulary generation.

#SFWApro

September 13, 2013

Friday Reads: The Thousand Names, by Django Wexler

A few weeks ago, I had a guest post by Django Wexler, as part of the promo effort for his debut fantasy novel The Thousand Names. I usually only do this for authors whose books I think will appeal to my readership, and I’m glad to say that I wasn’t wrong in this guess, at least if my own reaction to it is anything to go by…

In the desert colony of Khandar, a dark and mysterious magic, hidden for centuries, is about to emerge from darkness.

Marcus d’Ivoire, senior captain of the Vordanai Colonials, is resigned to serving out his days in a sleepy, remote outpost, when a rebellion leaves him in charge of a demoralised force in a broken down fortress.

Winter Ihernglass, fleeing her past and masquerading as a man, just wants to go unnoticed. Finding herself promoted to a command, she must rise to the challenge and fight impossible odds to survive.

Their fates rest in the hands of an enigmatic new Colonel, sent to restore order while following his own mysterious agenda into the realm of the supernatural.

I think The Thousand Names can best be summed up as “Sharpe does Napoleon’s Egyptian campaigns with a dash of Indiana Jones”. It’s a pretty low-fantasy story, at least for the first three-quarters of the book, focusing mainly on the day-to-day life of soldiers in a desert campaign. The tech level of the setting is roughly equivalent to late 18th/early 19th century Europe, with armaments including muskets, bayonets and a variety of cannon.

The star character has to be Winter Ihernglass, a young woman doing the historically well-attested thing of disguising herself as a man in order to join the army. As someone who has written a character very much like this, I enjoyed seeing Wexler’s take on the theme. Winter is hardy, resourceful and determined, but we never forget how vulnerable she is (though thankfully without any rape!); a truly strong female character who feels utterly realistic.

By contrast Captain Marcus d’Ivoire feels a little bland, but that may be because he has a lot less at stake. Sure, he’s under constant threat of death in battle, but so is everyone else. It isn’t until close to the end of the book, when he begins to suspect there are skeletons in his own family closet, that there’s a reason to think he might have an interesting personal arc ahead of him.

The book itself is something of a slow burn, and the second quarter consists almost entirely of a detailed account of a battle between the colonials and the rebels. Although I’ve studied a little military history, I’ve never gone into the minutiae of battle manoeuvres so I found these scenes hard work, trying to visualise all the details of the terrain and the troop deployments. Hence although these chapters are well-written, I confess I was relieved when the scale switched back to the individual characters’ level.

One thing that did slightly bother me was the worldbuilding. Despite its Afghan-sounding name Khandar is pretty much your standard North African/Near Eastern stereotype, with its self-centred puppet prince and his colonial allies ousted by a coalition of his own army and a bunch of religious fanatics, not to mention horse-riding desert raiders led by a mysterious masked character (The Desert Song, anyone? Or am I the only one old enough to remember that musical?). None of these elements is bad in itself, but together they feel a bit too much of a coincidence. Wexler tries to get away from identifying them racially as Arabs by giving them greyish skin, but it’s such a minor difference (and being visual, too easy to ignore in a book) that it feels like a token effort. Perhaps if we’d seen more of the Khandarai than their magic, there would have been enough cultural differences to throw the stereotypes into the shade, but the reader can only go by what’s on the page.

Flaws aside, this was a great book; it’s always a good sign when I find myself really looking forward to my next reading session. Like Brian McClellan, Wexler has released a prequel short story (“The Penitent Damned”), which I will definitely be checking out whilst I wait for the sequel, The Shadow Throne.

September 10, 2013

Constructed languages in fantasy & SF

A couple of years ago I blogged about how I’d gone about creating the languages for my alternate history fantasy series Night’s Masque. At the time, The Alchemist of Souls was undergoing final edits, so I felt it was a bit early to post any details of the languages. However, this month being the fortieth anniversary of the death of J R R Tolkien, I felt it was high time I did a new series of blog posts on the topic of conlangs (constructed languages).

In this first post, I’m going to cover the history of conlanging in SFF. In following weeks I’ll talk about how you might go about creating your own language, and finish up with some software tools that can help you with the task.

A Brief History of Constructed Languages

Conlangs existed well before Tolkien came along, of course. Probably the most famous is Esperanto, created in the late nineteenth century by the Polish doctor and linguist L L Zamenhof, though there are examples dating back much earlier. Most of these invented languages were intended to have practical applications: they included attempts to reconstruct the language of Adam and Eve and to develop a “perfect” language (according to various criteria), or were used for cryptography.

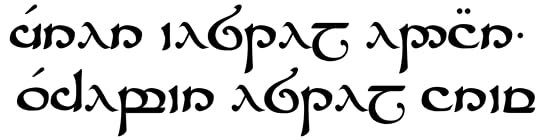

Tengwar (Sindarin script) by Xander, Wikimedia Commons

Tengwar (Sindarin script) by Xander, Wikimedia CommonsFor Tolkien, on the other hand, language-making was simply a hobby. He loved languages and wanted to make his own, just as SFF writers love to invent worlds. But whereas most modern writers start with a world and then create a language for it, Tolkien started with the languages and then wrote stories to give them a context. He even went so far as to create elegant scripts to write them in.

Whatever the reason, the languages gave his books a depth of verisimilitude that few have achieved before or since, and as with his fiction, there have been many imitators of this aspect of his worldbuilding. Before Tolkien (and, regrettably, after in some cases), invented names in SFF leaned towards the unpronounceable, such as H P Lovecraft’s Cxaxukluth and Xa’ligha. The apostrophe is particularly heavily overused;TV Tropes refers to this practice as the Punctuation Shaker. Even when there’s some kind of reason or consistency behind it (as with Anne McCaffrey’s dragon-riders, who shorten their names when they bond with a dragon to denote their change in status), the poor apostrophe has become such a mark of bad worldbuilding that many readers will run screaming at the sight of it!

After Tolkien’s elvish languages, the most famous conlang is probably Klingon, created by actor James Doohan for Star Trek: the Motion Picture and developed in detail by linguist Marc Okrand. So popular has it become that there is now a Klingon Language Institute that produces learning materials and translations of Earth literature and supports a community of conlang fans.

In recent years, the growth of the internet has enable the easy sharing of resources on basic linguistics, which has led to a better quality of conlangs. One of the pioneers of this new generation of conlangers is Mark Rosenfeld, a comics fan and linguist whose website has hosted The Language Construction Kit since 1996. (I’ll talk some more about the LCK next week, when we come to how to create your own language). At the same time, the use of Tolkien’s invented languages in the movie adaptations of The Lord of the Rings has exposed a whole new audience to the idea of language creation.

At WorldCon in Chicago last year, I was lucky enough to be invited onto a panel with both Lawrence Schoen, the founder of the KLI, and David Peterson, an American linguist and president of the Language Creation Society, who is best known for creating the Dothraki language for the TV series Game of Thrones. As far as I know, George R R Martin’s books feature Dothraki names but no actual examples of their language. However HBO decided to give them a language to speak on-screen that could then be subtitled, perhaps to emphasise their foreignness. They brought in Peterson as a consultant, and he has since gone on to create High Valyrian for the same show as well as the alien languages Castithan and Irathient for Syfy’s near-future SF series Defiance. If you’re interested in his work, you can find a number of websites online via his blog or follow him on Twitter, where he’s @dedalvs.

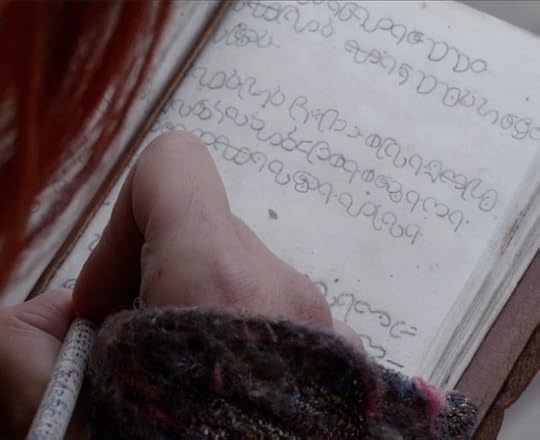

Irisa’s diary, from TV series Defiance

Irisa’s diary, from TV series DefianceI suspect that the popularity of these TV conlangs arises from the fact that you can hear the characters speaking them, rather than just seeing them written down on the page. That’s a big disadvantage to novelists, though with the growing popularity of audiobooks, perhaps there will be a resurgence of interest in constructed languages in books. When I created the skrayling languages used in Night’s Masque, I took particular care to make them pronounceable by an Anglophone reader, partly because I knew that Angry Robot had a new strategy of releasing audiobooks simultaneously with print formats so I knew they were destined to be read aloud. Fortunately I was assigned an excellent narrator, Michael Page, who managed to pronounce most of the examples of skrayling speech pretty accurately, and sometimes even better than I could manage! (I have no problem with fricatives in things like the Scottish place name Auchtermuchty, but can’t roll my ‘r’ sounds for toffee.)

That concludes my whistlestop tour of the history of conlangs. Next week: how to do it yourself!

September 6, 2013

Diversity in secondary world fantasy

There’s been a lot of debate in genre circles recently about diversity in fantasy – hell, I was on a panel about this very topic at AltFiction last year. It’s a very broad field, however, so I want to focus on one area that’s been on my mind for a while. Note that I’m writing this article from the perspective of a white Westerner; I’m very much in favour of a diversity of voices in SFF, but by definition that’s not an issue I can address in my own fiction.

Epic fantasy gets a lot of stick for being conservative in its worldbuilding: of cleaving to white, Western, European-inspired settings. And there’s a lot of truth in that. OK, so it’s hardly surprising, given that the acknowledged grandfather of the genre was a professor of medieval languages at Oxford University. But there’s a lot more to the world—and to human experience—than the culture of one small corner of it during a brief historical period.

By the way, I don’t believe there’s anything wrong with being inspired by the history and literature of your own culture; if I did, I wouldn’t have written a trilogy of novels set during the age of England’s greatest literary figure, William Shakespeare. Night’s Masque is alternate history set in our world, but there are plenty of examples of secondary world fantasy that, like Tolkien’s work, draw heavily on European history: a particularly famous one is A Song of Ice and Fire, which is based on the War of the Roses. I’m currently reading The Thousand Names by Django Wexler, which is clearly inspired by historical military fiction such as Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe novels, and thus the good guys are predominantly white and male (or in one case a cross-dressing woman). There’s a lot of pleasure to be had in writing what is in a sense “history fan-fiction”

The problem is that too many Western authors use European-based settings uncritically, as an unthinking default. They create yet another white, misogynistic, xenophobic culture because “that’s the way things were in those days”, ignoring a whole bunch of issues. For starters, that’s not necessarily the way things were. Medieval culture lasted a thousand years and spanned a continent; it wasn’t homogeneous, and the stuff you were taught in school omits a lot of surprising facts. Did you know for example that in the early Christian world, men could marry other men? That in 15th century England, women of the landed classes were expected to run their husbands’ estates, even leading the defence against attacks by rival knights and their private armies? I’ve had people tell me that my Elizabethan characters couldn’t possibly be blasé about homosexuality, when there’s ample historical evidence that sodomy was endemic in male-dominated Renaissance culture.

Statue of kickass medieval heroine Jeanne Hachette (photo: Marc Roussel, Wikimedia Commons)

Statue of kickass medieval heroine Jeanne Hachette (photo: Marc Roussel, Wikimedia Commons)And then of course there’s the fact that FANTASY WORLDS ARE MADE UP and we can therefore do whatever the hell we like with them! I’m not saying that every secondary world has to be a multicultural feminist utopia, but I’d like to see more writers put as much effort into worldbuilding their cultures as they do into their magic systems or the fucking heraldry of a hundred minor aristocrats. Ahem. Where was I?

Maybe it’s because I started my genre career as an avid SF reader, but it seems to me that there are as many possibilities for exploring the human condition in a fantasy setting as there are in SF. I did this a little in Night’s Masque, where I created a sentient species, the skraylings, that were based not on folklore but on biological and anthropological principles. The result was a culture very alien to my Elizabethan characters but consistent and, I hope, believable.

In my new project I’m taking the worldbuilding a step further, into secondary world fantasy, because that gives me more control over the human cultures. Yes, they take a good dollop of inspiration from European history at various periods, because that’s what I know and love. And yes, there will be hot guys with swords/crossbows/whatever at the heart of the action, because that’s what gets my creative juices flowing. But those guys won’t necessarily be white, or straight, or abled.

The thing is, this is my world, which means I’m free to make changes that simply wouldn’t work in a historical setting. I can give women a more equitable social status, make sexual orientation a non-issue, create a broader racial mix than would be seen in most pre-modern cultures; whatever makes the setting more pleasing to me—and more inclusive for my readers. It won’t be a utopia by any means—there are inequities of power in any society—but I don’t see why I should harp on the same old prejudices that dog our world. I want my writing to be fun, and misogyny, racism and homophobia are the polar opposite of that.

A brief aside on race in fantasy. In real-world settings you can rely on reader knowledge to fill in the details. Mention that a character is Chinese or Japanese and the reader will mentally add straight black hair and epicanthic folds (unless you say otherwise). Conveying race in a secondary world fantasy is a more delicate business, especially if you’re not filling it with close analogues of real-world cultures. And what about creating racial characteristics not found on Earth, e.g. different skin tones or combinations of colouring? So far in my work I’ve tended not to describe characters’ appearance in great detail, so this is an issue I’m going to be wrestling with in my new series.

Anyway, I guess my point is that you don’t have to throw away all the cool toys that you love—swords, castles, dragons, whatever—to write diverse, inclusive fantasy; a fondness for familiar tropes is no excuse for perpetuating hurtful stereotypes. The joy of fantasy is in stretching our imaginations, so why limit ourselves?

September 3, 2013

Previously on Night’s Masque…

As per last year, I’m making it easy for you to refresh your memory of the story so far, by posting a synopsis of The Merchant of Dreams on my website. Of course if you haven’t read the book itself yet, you’d better get your skates on

Also, a reminder of my October schedule, which is starting to fill up!

Saturday 12th – Wood Green Literary Festival

I shall be doing a reading and Q&A session along with fellow Angry Robot author Mike Shevdon – the theme of the festival is “London: a Celebration”, so we’ll be talking about our respective fantasy Londons and the history of the city. Of course we’ll also be available to sign books if you bring them along (or buy them).

Check out the programme for location and times: http://www.woodgreenlitfest.org.uk/saturdays-programme/

Saturday 26th – BristolCon

As per the past two years, I’ll be attending this compact and bijou convention in my alma mater, Bristol, and hopefully doing a panel or two and a reading, though the programme is yet to be confirmed.

Thursday 31st October – Forbidden Planet, London

I’m delighted to announce that I will be launching The Prince of Lies at Forbidden Planet in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, alongside Wes Chu’s The Deaths of Tao. A bunch of other Angry Robot authors are going as well, so this is your chance to meet us all for a chat – and pick up an exclusive early copy of the paperback edition, which isn’t officially released in the UK until November 7th!

Angry Robot Halloween Takeover!

31st October – 4th November – World Fantasy Convention, Brighton

Straight after the Forbidden Planet signing, I’ll be jumping on a train down to Brighton for World Fantasy, where I’ll be hanging out with writer friends and hopefully doing a reading.

I look forward to seeing you at one or more of these events

August 30, 2013

I&E follow-along: spotting problems

Whether you outline in detail or just make some basic notes on characters and conflict (HtTS Lesson 8), this is your chance to figure out if the choices you’ve made are leading you in the right direction.

I had this issue with the protagonist of Book 1 of this new series. I chose a profession for him based on what I thought would be cool and useful further down the line, but when I came to work out how he’d acquired these skills, I realised there was a modern-day parallel that would take me into politically sensitive territory. In another book or in the hands of another writer that might be fine – but it was the wrong direction for this series.

So, I sat down and worked out which parts of his backstory I had to throw out and which I could keep, then took his life in a different direction that would nonetheless bring him to the place I’d envisaged the book beginning. As a bonus, it’s changed his personality in ways that I think will fit far better with the plot I have in mind, as well as totally solving the naming issue I was having.

In summary: don’t be afraid to interrogate your ideas. Better to throw out five hundred words of outline (as I did) than twenty five thousand words of first draft!