Anne Lyle's Blog, page 4

March 25, 2014

“Lost” 17th century fencing manual – now in print!

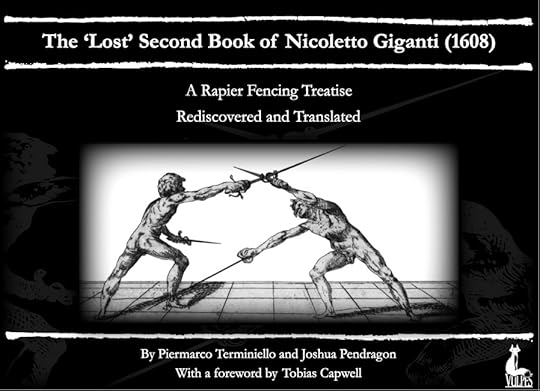

On Saturday 22nd March I attended the launch of a very exciting non-fiction book – an English translation of Nicoletto Giganti‘s second fencing manual, which until very recently had been lost to history.

The story of its discovery is up there with that of Tutankhamen’s tomb: a missing piece of the historical jigsaw that had faded almost into legend, suddenly found by a couple of bold adventurers. Admittedly the journey of discovery required only a visit to the Wallace Collection in central London, not to Egypt, but for those of us who love Renaissance history, it was just as exciting.

To give some context, there were many famous Italian masters writing fencing manuals in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, of which Nicoletto Giganti was one of the more highly regarded. His first manual was published in 1606 and covered the basic techniques of rapier fighting, but in it he promised to write further books that would expand upon this foundation. A sequel was duly published in 1608, but no copies were known to have survived, and even as early as 1673 some experts expressed doubts that it had been written at all. To complicate the issue, Giganti’s first book was reprinted several times in the 17th century, at least once in Italian and then in German translation, so there are numerous editions of it in the various collections around the world.

Renaissance fencing enthusiasts Piermarco Terminiello and Joshua Pendragon had heard there was a 1608 book by Giganti in the Wallace Collection, and were hoping very much that it was the second book and not a reprint of the first. The book itself had been overlooked because its illustrations were inferior to the first manual, giving rise to the assumption that it was a cheap rip-off! But when Pim and Josh started flipping through it, they realised that the illustrations didn’t match the first book’s text at all: here were pictures of the fighting techniques Giganti had promised to cover in his sequel, such as rapier and dagger, rapier and shield, and grapples. Returning to the frontispiece, the title was unequivocal: LIBRO SECONDO, in huge capitals!

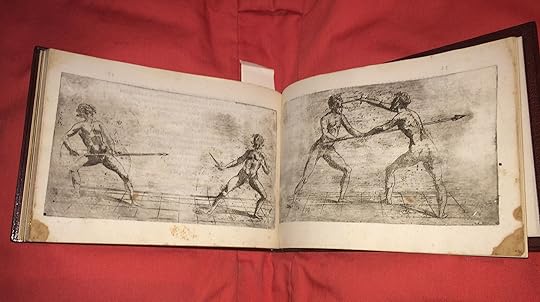

The precious sole copy of Giganti’s second book – this “dagger vs spear” illustration is one of the more advanced techniques covered

The precious sole copy of Giganti’s second book – this “dagger vs spear” illustration is one of the more advanced techniques coveredAfter months of work, first on an academic paper and then on the translation itself, the paperback edition was launched at the Wallace Collection. The Curator of Arms and Armour, Tobias Capwell, introduced the authors, then after a brief introduction to the topic by Joshua Pendragon the audience was treated to a more in-depth presentation by Piermarco Terminiello. Not only was the talk very entertaining in itself, but it was accompanied by live demonstrations of some of the moves by member of The School of the Sword.

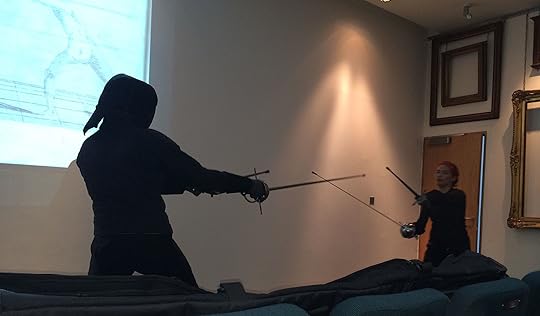

Fran Terminiello (right) takes on a mysterious hooded assailant!

Fran Terminiello (right) takes on a mysterious hooded assailant!Of course I bought a copy after the talk. For a writer of historical fantasy like myself, primary sources are so valuable in helping to envisage what real Renaissance swordplay looked like. In addition, Giganti’s second book covers just the kind of fighting one is likely to come across in a novel; not the stylised duelling of the salle, but the grapples and improvised tactics that – as Giganti says – will serve a man well on the dangerous city streets!

I am of the opinion, that the dagger is as important for a gentleman to know as any other weapon. This is because the majority of great men and captains who are killed, are slain by daggers or similar arms.

Nicoletto Giganti, 1608

I’m only sorry that this book wasn’t around when I was writing my Elizabethan novels – the cudgel- and knife-fighting techniques that Mal teaches to Coby in The Alchemist of Souls are based on other similar manuals of the period. However Giganti certainly bears out the approach I took, and I hope that his instructions will come in handy in future novels

Should you want to find out more:

A paperback edition of the translated manual, published by Fox Spirit Books, can be obtained from Amazon.

Fran Terminiello (Pim’s wife) is doing a swordplay demonstration at this year’s Edge-Lit SFF convention in Derby

The Wallace Collection is home to a fine collection of medieval and Renaissance arms and armour (as well as many famous paintings) and best of all, entrance is free!

March 18, 2014

Diagramming your book’s conflicts

This weekend I knuckled down to sorting out the overall plot of my work-in-progress, Serpent’s Tooth. I have a setting, several main characters and some ideas for conflicts, but nothing was pinned down, hence my struggles to get on with writing the book. This is pretty par for the course with me; I tend to get bogged down in plot possibilities because there are so many directions the story could go in and I can’t decide which one is best!

I started with my usual process of “thinking aloud” on paper, and suddenly the pieces began to fall into place: I knew who my main opposing factions would be, and that there would be factions within those factions, divided loyalties, betrayals, etc. It was starting to get quite complicated, so at the suggestion of my writer friend Adrian Faulkner I broke out my trial copy of Scapple, a simple diagramming program for Mac and Windows, produced by those lovely people who brought us Scrivener.

I started drawing boxes, connecting them with arrows and colour-coding them by their allegiances, and I realised this was a really useful tool for fleshing out your conflicts. I’m not usually big on mind-maps for brainstorming, as they don’t help me figure out why people are connected, but it turns out they’re excellent for summarising the results of my brainstorming – and for provoking new brainstorming to fill in the gaps! It’s not really anything new, I guess, but I was so excited by how much clearer my ideas became that I wanted to share my methodology.

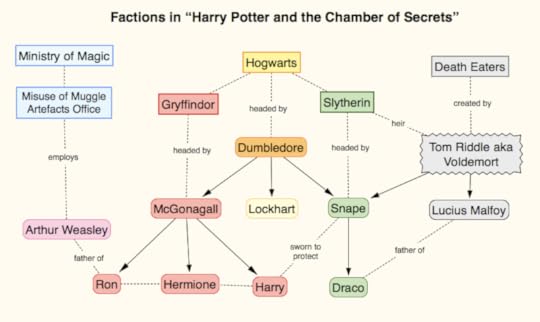

Obviously I can’t show you the diagram for Serpent’s Tooth—spoilers!—so instead I’ve mocked up some examples using the first two Harry Potter books. This series has the advantage that a) it’s extremely well known and b) the conflicts are simple enough to fit in a small diagram but complex enough to illustrate the principles well.

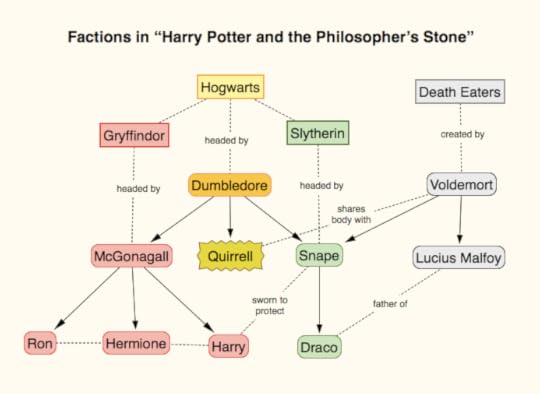

I’ve chosen to follow a few simple conventions for my diagrams:

Square-edged box – an organisation, group or faction

Round-edged box – an individual

Arrow – a superior-to-inferior relationship in a formal hierarchy (e.g. boss-to-employee)

Dotted line – any other kind of relationship

I’ve also marked the principle villain in each book with a jagged-edged box, just for clarity.

First, let’s look at Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone:

There are two principle factions at Hogwarts, Gryffindor and Slytherin, which I’ve coloured red and green respectively (based on their house colours). Note that whilst Hogwarts in general is represented by yellow, I’ve chosen orange for Dumbledore because he has a distinct bias towards Gryffindor. Professor Quirrell on the other hand is a dirty yellow, to signify his corruption by Voldemort. Quirrell is also the main antagonist in this book, since Voldemort is still lacking a body of his own.

Already we can see that Snape is going to be a crucial character because he belongs to two opposing factions. I think this diagram also shows why the series appealed so much to adults; although the action is focused on the younger generation, the most interesting conflicts revolve around the older wizards, giving the adult characters a far more prominent role than is usual in children’s fiction.

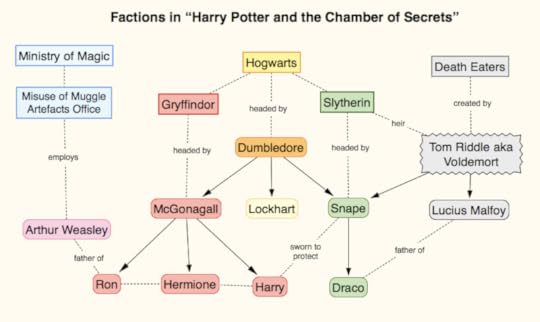

Moving on to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, we see the conflict expanding beyond Hogwarts into the wider world:

The new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Gilderoy Lockhart, is nowhere near as central to the plot as Quirrell was; instead the main villain is now Voldemort, or rather his past self Tom Riddle and his diary/horcrux.

Now you’re probably wondering why I bothered to include the Ministry of Magic on my chart – after all, it doesn’t play much of a role in this book. I would indeed omit it, except that it’s a great opportunity to illustrate what I discovered whilst working on my own book’s conflicts.

When Ron steals the flying car, it seems at the time like nothing more than a fun incident, but it also serves to introduce the ministry and hint at conflict between its authoritarian attitude and the Weasleys’ (and Dumbledore’s) more laid-back approach. If however Rowling had decided to expand this storyline in Chamber of Secrets, there’s a problem with the diagram as it stands: there is no-one who personifies the ministry, and therefore no-one whom the protagonists can confront.

What Rowling would need to do is add senior figures at the ministry: Mr Weasley’s boss, Barty Crouch Sr, and perhaps even the Minister for Magic himself. And of course she does exactly this in later books, fleshing out the ministry’s hierarchy as its members become almost as big a threat to Harry and his friends as the Death Eaters.

My point is that if you draw up your conflict diagram and discover that an important faction (i.e. one with a major stake in the plot) has no representative, that’s a good indication that you need to create such a character. Without them, the faction will be a faceless organisation and thus far harder for your protagonists to interact with. Secondly, if your factions are monolithic blocks with no disagreements or divided loyalties, you’re missing out on some great story opportunities. Finally the diagram is a good way to get a grasp of all the connections between characters, and helps you to see where additional connections might enrich the plot.

Of course my “discovery” is hardly headline news, but on the other hand I’ve read many, many books of writing advice and yet I don’t recall seeing any that explain in a simple, visual way how to populate a plot with the characters you need. Maybe everyone else finds it intuitive, but surely I can’t be the only writer in the world who sometimes struggles with defining conflicts?

Anyway let me know if you find it useful!

Diagramming your book’s conflicts

This weekend I knuckled down to sorting out the overall plot of my work-in-progress. I have a setting, several main characters and some ideas for conflicts, but nothing was pinned down, hence my struggles to get on with writing the book. This is pretty par for the course with me; I tend to get bogged down in plot possibilities because there are so many directions the story could go in and I can’t decide which one is best!

I started with my usual process of “thinking aloud” on paper, and suddenly the pieces began to fall into place: I knew who my main opposing factions would be, and that there would be factions within those factions, divided loyalties, betrayals, etc. It was starting to get quite complicated, so at the suggestion of my writer friend Adrian Faulkner I broke out my trial copy of Scapple, a simple diagramming program for Mac and Windows, produced by those lovely people who brought us Scrivener.

I started drawing boxes, connecting them with arrows and colour-coding them by their allegiances, and I realised this was a really useful tool for fleshing out your conflicts. I’m not usually big on mind-maps for brainstorming, as they don’t help me figure out why people are connected, but it turns out they’re excellent for summarising the results of my brainstorming – and for provoking new brainstorming to fill in the gaps! It’s not really anything new, I guess, but I was so excited by how much clearer my ideas became that I wanted to share my methodology.

Obviously I can’t show you the diagram for Serpent’s Tooth—spoilers!—so instead I’ve mocked up some examples using the first two Harry Potter books. This series has the advantage that a) it’s extremely well known and b) the conflicts are simple enough to fit in a small diagram but complex enough to illustrate the principles well.

I’ve chosen to follow a few simple conventions for my diagrams:

Square-edged box – an organisation, group or faction

Round-edged box – an individual

Arrow – a superior-to-inferior relationship in a formal hierarchy (e.g. boss-to-employee)

Dotted line – any other kind of relationship

I’ve also marked the principle villain in each book with a jagged-edged box, just for clarity.

First, let’s look at Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone:

There are two principle factions at Hogwarts, Gryffindor and Slytherin, which I’ve coloured red and green respectively (based on their house colours). Note that whilst Hogwarts in general is represented by yellow, I’ve chosen orange for Dumbledore because he has a distinct bias towards Gryffindor. Professor Quirrell on the other hand is a dirty yellow, to signify his corruption by Voldemort. Quirrell is also the main antagonist in this book, since Voldemort is still lacking a body of his own.

Already we can see that Snape is going to be a crucial character because he belongs to two opposing factions. I think this diagram also shows why the series appealed so much to adults; although the action is focused on the younger generation, the most interesting conflicts revolve around the older wizards, giving the adult characters a far more prominent role than is usual in children’s fiction.

Moving on to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, we see the conflict expanding beyond Hogwarts into the wider world:

The new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Gilderoy Lockhart, is nowhere near as central to the plot as Quirrell was; instead the main villain is now Voldemort, or rather his past self Tom Riddle and his diary/horcrux.

Now you’re probably wondering why I bothered to include the Ministry of Magic on my chart – after all, it doesn’t play much of a role in this book. I would indeed omit it, except that it’s a great opportunity to illustrate what I discovered whilst working on my own book’s conflicts.

When Ron steals the flying car, it seems at the time like nothing more than a fun incident, but it also serves to introduce the ministry and hint at conflict between its authoritarian attitude and the Weasleys’ (and Dumbledore’s) more laid-back approach. If however Rowling had decided to expand this storyline in Chamber of Secrets, there’s a problem with the diagram as it stands: there is no-one who personifies the ministry, and therefore no-one whom the protagonists can confront.

What Rowling would need to do is add senior figures at the ministry: Mr Weasley’s boss, Barty Crouch Sr, and perhaps even the Minister for Magic himself. And of course she does exactly this in later books, fleshing out the ministry’s hierarchy as its members become almost as big a threat to Harry and his friends as the Death Eaters.

My point is that if you draw up your conflict diagram and discover that an important faction (i.e. one with a major stake in the plot) has no representative, that’s a good indication that you need to create such a character. Without them, the faction will be a faceless organisation and thus far harder for your protagonists to interact with. Secondly, if your factions are monolithic blocks with no disagreements or divided loyalties, you’re missing out on some great story opportunities. Finally the diagram is a good way to get a grasp of all the connections between characters, and helps you to see where additional connections might enrich the plot.

Of course my “discovery” is hardly headline news, but on the other hand I’ve read many, many books of writing advice and yet I don’t recall seeing any that explain in a simple, visual way how to populate a plot with the characters you need. Maybe everyone else finds it intuitive, but surely I can’t be the only writer in the world who sometimes struggles with defining conflicts?

Anyway let me know if you find it useful!

February 11, 2014

2014 convention schedule

After a certain amount of umming and ahhing, I’ve finally locked down my convention schedule for 2014. It’s a busy one, mostly because there are so many awesome cons around and I don’t want to miss out!

N.B. Panels and other events will be confirmed nearer the time.

18-21 April: Satellite 4 (Eastercon), Glasgow

I shall only be staying in Glasgow a couple of nights as I wasn’t sure of my convention budget when the time came to book everything, but there’s no way I’m going to miss the first big UK convention of the year!

3-6 July: CONvergence, Bloomington, Minnesota

I’m really excited about this one, as a) it’ll be my first trip to the US in 18 months; b) it’s a great chance to see some of my Midwestern friends; c) it’s reckoned to be a great convention and d) what could be better than a theme straight out of Shakespeare?

8-10 August: Nine Worlds Geekfest, London

Last year was awesome considering this is a brand new con, and this year is set to be at least as good – and this time it will be held at the Radisson Edwardian, the venue of my debut book launch and thus site of many happy memories.

14-18 August: Loncon 3 (WorldCon), London

The big one – and only the third WorldCon in our fair capital, ever! Some of my US buddies are coming over, which will make it doubly brilliant. Plus, as with World Fantasy last autumn, the guest list is going to be stellar. I just hope I can get through two conventions back-to-back without a repeat of the Cold From Hell that I had last autumn!

5-7 Sept: FantasyCon, York

A favourite convention of mine, for sentimental reasons – I made loads of writer friends at previous FantasyCons and of course it’s where I met my editor Marc Gascoigne and his trusty sidekick Lee Harris. There had better be a disco this year, though – it was sorely missed last year owing to the “merger” with WFC.

25 October: BristolCon, Bristol

The convention season usually ends for me with a trip to my alma mater, and 2014 is no exception. I love the cosy atmosphere – the venue is so small, there’s little chance of missing anyone (except for that sneaky Mark Lawrence chap, whose lightning visits make him the most elusive of authors!).

So, that’s my 2014 in a nutshell! In the unlikely event that you own one of the rare unsigned copies of The Alchemist of Souls (or any of my other books), please feel free to introduce yourself (unless I’m eating or attending to other bodily needs…).

See you there!

January 31, 2014

Friday Read: The Dragon’s Path, by Daniel Abraham

Way back in 2011 (gosh, was it really that long ago?) I read Abraham’s debut, A Shadow in Summer, and loved it for its beautiful writing and unusual Eastern-inspired setting, so when I heard he had written a more conventional epic fantasy series I was a little conflicted. I couldn’t blame him for wanting to write something more commercial than The Long Price Quartet, but I’m not a huge fan of bog-standard medieval EF so it didn’t exactly leap to the top of my TBR list. However I’m currently waiting on several much-anticipated books that aren’t out until spring, so I decided to bite the bullet and give The Dragon’s Path a go…

The dragons are gone, the powerful magics that broke the world diluted to little more than parlour tricks, but the kingdoms of men remain and the great game of thrones goes on. Lords deploy armies and merchant caravans as their weapons, manoeuvring for wealth and influence. But a darker power is rising – an unlikely leader with an ancient ally threatens to unleash again the madness that destroyed the world once already. Only one man knows the truth and, from the shadows, must champion humanity. The world’s fate stands on the edge of a Dagger, its future on the toss of a Coin . . .

Abraham is well-known for his collaborations with George R R Martin, and I have to say that it really shows in this novel. Handful of medieval kingdoms jockeying for power? Check. Weak king beset by ambitious nobles? Check. Dragon skeletons littering the landscape? Check. Scary evil lurking on the far edge of the world? Check. Even the names of many of the characters – Jorey Kalliam, Geder Palliako, Paerin Clark – sound like they could have stepped right out of Westeros. It’s pretty obvious, in fact, that the publishers were aiming squarely at GRRM’s readership: not only do they have the great man’s endorsement on the front cover, but they even managed to get the words “game of thrones” into the back cover copy. Subtle marketing this ain’t!

And yet this book is a rather different beast from A Song of Ice and Fire; less brutal, at least in this first volume, and far more female-friendly. Which is not to say that all is sweetness and light. One character starts out as a likeable buffoon but when his superiors humiliate him one time too many, he takes his revenge in a breathtakingly dramatic manner that reminded me very much of Londo Mollari, one of my favourite characters from the TV series Babylon 5 (and I’m not the only one). Abraham also balances out his military storyline – the Dagger referred to in the series title - with one about banking, i.e. the Coin.

The banking storyline centres around Cithrin bel Sarcour, a ward of the Medean bank who, disguised as a boy, escapes the tide of war with a cargo of valuables, guarded by jaded mercenary captain Marcus Wester, his gruff second-in-command Yardem (a not-quite-human – of which more later), and a bunch of actors pretending to be his crew. Sound familiar to my readers? Indeed, the further I read, the more it felt like a bunch of characters from Night’s Masque had wandered into a Joe Abercrombie novel by mistake

Cithrin is a wonderful character: at first terrified by the situation she has been thrust into, she gradually gains self-confidence and shows herself to be highly intelligent and capable, yet still possessing the vulnerability of a girl on the cusp of womanhood. I also liked Clara, wife of one of the other PoV characters, who becomes a PoV herself later in the book; she’s a woman locked out of power in a patriarchal aristocracy, who nonetheless provides insight and resourcefulness to counter the male characters’ head-on approach to problems. As with The Long Price Quartet, Abraham shows himself adept in writing strong, interesting female characters, with nary a rape in sight!

If I have one major criticism of this book, it’s that the other humanoids are too thinly developed. There are normal humans like us, called Firstbloods, plus (IIRC) twelve additional “races” created by dragons thousands of years ago, most of whom can interbreed with Firstbloods. They have a variety of distinctive physical characteristics – the Cinnae are thin and pale, the Kurtadam are furry and otter-like, the Jasuru have scales – but otherwise their only purpose in the story seems to be to allow racial tensions without the real-world baggage. There’s little sense that these are separate peoples with their own cultures, and OK, maybe they aren’t, but it made for a kind of thin, underdeveloped multiracial culture. Even when one of the PoV characters ventures into a part of the world where Firstbloods are rare, it’s easy to forget that the foreigners he is interacting with aren’t exactly human – they’re just not as alien as I would like. I don’t know if Abraham is deliberately playing safe by not taking his readers out of their comfort zone or whether this is an aspect of worldbuilding he’s not particularly interested in, but it felt like window-dressing to me.

The writing also felt a bit sub-par compared to Abraham’s earlier work – lots of repetition of words within sentences, and not in a poetic sense. This added to my feeling that the genesis of this series was driven by a desire to rapidly fill the ever-longer gaps between volumes of ASOIAF. Still, I doubt most readers will even notice; being a writer oneself, it’s almost impossible to turn off the editorial voice when reading what should be polished work!

One final nitpick that’s more specific to my interest in history is Abraham’s apparent lack of knowledge in some areas. There’s his habit of referring to noblemen as Sir , instead of Sir or Baron Whatsit and, worse still, a sword fight in which he mentions the “blood channel” on the blade. If you don’t know why I’m annoyed, or just want to know where the idea comes from, I’ve discovered a great article on the myth of the blood groove (its actual name is the fuller). I was totally thrown out of a tense fight scene by my astonishment that an otherwise good writer would make such amateurish mistakes. OK, so this is a made-up world, but I feel that if you’re going to base your culture so closely on a real-world one, you should get the language right, otherwise it comes across as sloppy.

From all this criticism you’d be forgiven for thinking that I didn’t enjoy the book, but honestly its faults are so minor that they merely knocked it down from five stars to four – if I have been sparing in my praise, it’s mainly to avoid specifics that would constitute spoilers. With its engaging characters and well-paced, deftly woven plot (and, crucially, none of the “grimdark” aspects that have made me abandon other similar series) The Dagger and the Coin is close to my ideal epic fantasy. I shall certainly be picking up the second volume to find out what happens next!

January 28, 2014

The Musketeers

So, the BBC have a new “historical” drama series based on that much-loved classic The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas. So far, so awesome for any fan of swashbuckling action, right? Well, yes and no…

Mmm, look at all that leather! (Photo: BBC)

Mmm, look at all that leather! (Photo: BBC)On the one hand, The Musketeers offers a wealth of eyecandy to…I was going to say ‘ladies’, but maybe that’s too heteronormative – to anyone who appreciates the sight of attractive young men in leather doublets and bucket-top boots. The settings are excellent too; the series is filmed in the Czech Republic, which stands in for so many historical locations these days. I also love the opening titles, which have a “Young Guns” vibe, blending gorgeous artwork with live action to a foot-stomping theme tune.

One the other hand, sticklers amongst us may have a few gripes. The swordplay isn’t exactly stunning – the actors wield their rapiers more like broadswords, slashing where they should be lunging – and the dialogue can be clunky at times. Peter Capaldi, who has excelled in many roles including the infamous Malcolm Tucker in The Thick of It, somehow lacks the necessary scenery-chewing presence as Richelieu that this light-hearted drama requires. Given his riveting presence in other shows, I can’t help but wonder if the director is more to blame than Capaldi himself?

I was particularly pleased to discover that Santiago Cabrera had been cast as the womanising Aramis. Having seen his appearance in early episodes of Merlin, I picked him out as an actor I’d love to see cast as my own Mal Catlyn (though Aidan Turner will always be my first choice). So, watching Cabrera run around with rapier and pistol is a nice substitute for getting to see Night’s Masque itself made into a TV show

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre DumasTo me as an amateur historian, though, the most interesting aspect of the series is the casting of black actor Howard Charles in the role of Porthos (far right in the above photo). Before anyone cries tokenism, I’d like to point out that Dumas himself was mixed-race: his paternal grandmother, from whom he took his surname, was a black slave in Haiti. It’s so easy to view our past through the whitewashed lens of previous generations – frankly it’s about time we admitted that Europe has always had a small but nonetheless real and ubiquitous black population.

The Musketeers may not be up to the standards of great BBC dramas such as Pride & Prejudice or Sherlock, but it’s a fun show that will hopefully bring a classic story to the attention of a new audience.

More about The Musketeers on the BBC website

January 21, 2014

GTD for beginners, part 3

Unlike many organisation methods, Getting Things Done works in a bottom-up way; that is, you start with the small tasks and work your way up to the big picture. This has the advantage that you can get to work right away and only have to worry about the long term once you have the day-to-day landscape under control. However you can’t put off the higher-level planning forever!

NB: If you haven’t read my other posts on GTD, don’t start here – the first post is GTD for beginners, part 1 (obviously)!

Someday, Maybe…

British Airways 747. Photo: François Roche

British Airways 747. Photo: François RocheNo doubt when you started listing projects, you came up with some that you haven’t currently got the time or money to pursue. Maybe it’s a story idea, or a holiday destination, or a long-term plan like buying a house or going back to college. Rather than leave these as “open loops” that nag at the back of your mind, GTD encourages you to create them in a category called “Someday/Maybe”. If you’re using GTD software, these blue-sky projects don’t get listed under Next Actions, so you aren’t distracted by them during your daily work, but neither do you have to worry about forgetting them.

Still, they can’t be ignored forever, otherwise you’ll never get to do that cool stuff. That’s where your regular Review comes in.

Reviews

It’s a good idea to set aside some time every week to go through all your projects, to ensure that each one is on track and you haven’t overlooked anything.

Whilst you don’t want to review your Someday/Maybe category every week, it’s a good idea to look it over once in a while and see if there are any projects you can move off the backburner yet. I would do this no more than once a month, but probably no less frequently than once every three months.

Conclusion

GTD can be as simple or as complex as you like, but either way it really does help you keep a handle on your responsibilities so that you can Get Things Done!

If you want to get into the process in more depth than described in this short series of articles, I strongly recommend reading the original book, Getting Things Done by David Allen. You might also be interested in the 43 Folders website, named after the paper-based version of managing recurring tasks (31 folders for the days of the month + 12 for the months of the year).

January 15, 2014

Guest post: Kameron Hurley on combat in fiction

This week I’m delighted to host an article by award-winning author Kameron Hurley, whose Bel Dame Apocrypha trilogy is at last being published in the UK. Kameron and I first met in 2012 at Chicon 7, where she was giving away books if you ate a bug (dried mealworms and crickets, designed for human consumption, I would add!); I ate several bugs but did not take a book, for the sake of my luggage allowance, but would heartily recommend her work if you’re into SF with tough female characters.

Inside the Ring: Crafting Believable Combat in Fiction

Once upon a time, I took boxing and mixed martial arts classes. For the first time in my life, I learned to appreciate the power my body was capable of generating.

One fist. One punch. Power.

Boxing classes taught me the physicality of close combat. I’ll never know what it’s like to fight in a war (let’s hope) or to kill someone (let’s hope), but what I did have was the ability to learn how to throw and take a punch. What I couldn’t get a feel for in the ring, I could pick up by talking to others and through extensive research.

It wasn’t a huge surprise, then, that when I was trying to come up with a fighting style for the folks in my novel, God’s War, I leaned heavily on my knowledge of boxing, kickboxing, and Krav Maga. I liked the rawness and physical brutality of these styles. It wasn’t about being pretty. It was about getting results.

What I didn’t realize before I started taking classes was that there was also a lot more to stepping in the ring than just hitting hard. Anybody can throw one great punch. The trick was to be able to keep on throwing them – and taking them – for long periods of time. Fighters needed endurance. I found myself jogging three miles, twice a week, on the Chicago waterfront in blistering cold, just so I could keep up with the punching drills in class. If someone would have told me that being better at boxing meant cardio, I would have quit before I started.

But it did give me good details for the worlds I created. The better fighters, like better zombie evaders, kept up on their cardio.

Even now, years after taking classes, I can still close my eyes and work myself into a situation similar to my characters’. I can block it out. Imagine their footwork. Don’t ever ask me to dance, because I’m terrible at it, but I’ve gotten pretty good at blocking out a fight scene.

If you can’t rely on personal experience of some kind – or, even if you have some passing experience taking a martial art – your details are only going to be richer if you do your homework. Watch boxing matches. Watch MMA fights. Read about medieval combat. Scour books for firsthand accounts. Talk to friends with military training. Not long after graduating high school, a number of my friends became Marines, and were delighted to show me all the different ways they’d learned to kill people. It’s an unsettling thing to realize your friends have become trained killers, but it should feel surreal. Because if you’re writing fight scenes in a world that’s incredibly violent, like the one in my novels, people are going to be pretty different. It should feel that way.

Here are some things to keep in mind when writing fight scenes:

Blocking. Where are the combatants located? I’m pretty good at mapping things out in my head at this point, but when you have complicated battles, or those involving armies on a grand scale, it might be worth hauling out a pen and paper or some D&D minis and figuring out where everybody is and where they’re going. My theater training also came in handy here, believe it or not. When I’d memorize my lines for a show, I’d also memorize my blocking, my movements with each line, so I got used to mapping out virtual situations in my head. Having a second person read what you’ve written helps, too. I had a reader once email me to note that the left uppercut my character threw was actually a set up for a right hook, not a left hook (I’d written left. So they’re punching up with the left, pulling back, and punching around again with the same arm, which is a wasted movement, and counterintuitive. Just try standing up and trying to throw those punches – two lefts or a left, then right. Pretty clear which is the winner). But sometimes this stuff gets through when you’re writing quickly. When in doubt, stand up and block it out with a friend. Nicely.

A selection of replica weapons at the Globe Museum. Photo: Anne Lyle

A selection of replica weapons at the Globe Museum. Photo: Anne LyleWeapons. Do your fighters have weapons, or bare fists? If weapons, you’ll need to know the potential reach and damage of those weapons. I made up a lot of different types of fantasy/science fictional weapons for the God’s War universe, from scatterguns to acid rifles to organic pistols. I needed to figure out how many shots each had, at what distance they were accurate (more or less, depending on the skill of the user), how heavy they were, where my characters stored them (at the hip? Strapped to the thigh? Across the back? Over the shoulder?) and of course the shape – which is important for when they’re out of ammo and hitting people with them. Large differences in the height/reach of your characters are also going to matter. My spouse likes to tell a story of when a bully with a shorter reach once challenged him to a fight. My spouse is nearly 6’4”, and was able to snap out and hit the guy easily without ever being within the other guy’s shorter reach. Fight over.

Skill of combatants. Is you protagonist a good shot? Have they been formally trained on how to throw a punch? Is this their first fight, or their 50th? Have they fought for a living? Are they war veterans, or do they have military training? The way a character thinks about and approaches a fight is going to vary based on their training. Good, decent people with training actually try hard to avoid a fight with a less skilled opponent. This is because if you’ve been trained to kill people, getting into a fight with a screaming frat boy or blustering sorority sister is a life-or-death match that the better trained fighter knows the other isn’t ready for. Fighters with training will always beat fighters without, often with a single blow. The fights that stretch out are blustering-drunk-fights among the unskilled or fights between equally skilled opponents. It’s often shocking to realize how fast most fights are over. It’s not all thirty minutes of KungFu drama. Even boxers are quickly shuffled off the circuit if they can’t give the audience “a good show.” Which means sticking it out for several rounds. Nobody likes a one-hit wonder match.

Number of combatants. This is related to blocking, as it’s important to know exactly how many folks you have in motion at any one time. For massive campaigns involving hordes of troops, the best resources are historical ones. I have a great book called 100 Battles that Shaped the World that gives me historical overviews and troop movement maps for great battles from antiquity to the modern day. My research assistant found some strong resources, too, including this interactive timeline for the battle of Gettysburg. For small-scale combat, writing scenes where one person takes on a group are… well, they are Hollywood at best. In real life, you’d need to create a crazy Conan-type character or a single character with superior weaponry to successfully take on a group (which, yes, I do quite a lot because I love Conan). Again, when you have, say, three people of equal fighting ability and it’s two on one, the person who’s fighting on their own is pretty much fucked unless they are incredibly smart about using their environment to get away – running, dodging, leaping. Running, basically. I had a martial arts instructor tell me that once I moved into a fighting stance in response to an attacker instead of running, I’d chosen to fight. So I needed to be seriously sure I was ready to start a fight before committing to that stance. It’s a commitment I have my characters very aware of making as they slip into it instead of running. There’s always a choice. What your character chooses to do is interesting in and of itself.

Women have always fought. Everything I’ve said here goes for combatants of every type. When building fictional worlds, remember that it’s a good time to challenge your own expectations for who fights, and why. Women have of course fought in regular armies, revolutionary armies, and in individual combat forever. It’s something folks sometimes forget when they put together their armies, militias, patrols, and bar fights. Writing my God’s War trilogy forced me to interrogate my default assumptions for secondary characters of all types. With all men drafted at the front, every spear carrier – from the bartender to the boxing ticket manager to the security personnel outside the bounty hunting reclamation office – were default female.

I don’t take any fighting classes these days, because of jobs and mortgages and dogs and commutes. But when I sit down at my desk I can still close my eyes and go back there. In truth, I’m there every day, stepping into the ring with my characters, letting them take the blows meant for me.

Sometimes they’re pissed at me. I tell them it builds character.

ABOUT Kameron Hurley

Kameron Hurley is an award-winning writer and freelance copywriter who grew up in Washington State. She is the author of the book God’s War, Infidel, and Rapture, and her short fiction has appeared in magazines such Lightspeed, EscapePod, and Strange Horizons, and anthologies such as The Lowest Heaven and Year’s Best SF.

January 7, 2014

GTD for beginners, Part 2

This week’s post is a tad later in the day than planned, as I’m back at the day-job this week and – more crucially – didn’t put “Write next GTD blog post” in Things (the ToDo app I use on my phone and various Macs). A good example of why you should write things down the moment they occur to you!

So, last week I talked about setting up your buckets: places to save everything that needs dealing with, whether it’s a bill to be paid (your in-tray) or a blog post that needs writing (your notebook or ToDo app). If you’ve been following along, you’ll probably have a long list of stuff in your bucket and may be feeling a little overwhelmed by it all! Don’t panic – today I’m going to cover organising your tasks.

Note: I’m deliberately not following the “getting started” method described in the original GTD book, as that requires you to spend a whole day (or weekend) setting up your system, which I think can be a bit overwhelming! Instead I’m taking a “baby steps” approach, introducing concepts as and when you need them.

Next Actions

A key concept in GTD is that of Next Actions. By focusing only on what you can/must do next, you avoid the panicky flailing around that often accompanies a long ToDo list.

If you look at your current list, some items are probably single actions, e.g. “return library books” or “iron dress shirt for party” whilst others are really entire projects, like “write a novel” or “repaint living room” – things that are going to take a lot longer than an hour or two! These latter projects need to be broken down into their individual steps, e.g.

Pick up paint swatch leaflets from DIY store

Choose paint colours

Buy paint and brushes

Wash walls

etc, etc.

If you’re using a GTD-capable app like Things or OmniFocus, it’ll have a Projects mode built in; if you want to keep things simple with a basic checklist approach, look for an app that allows you to organise lists into folders or subtrees, e.g. Notebooks or CarbonFin Outliner (these are all iOS/Mac apps, btw – I’m afraid I’m not up-to-date on Windows software).

If you’re working on paper, you’ll need a second notebook or, even better, a looseleaf binder (in addition to your “bucket” notebook) – use a page per project and list your tasks in the order they need doing. This is one area where software makes life so much simpler, since you can reorder tasks at will.

You can also group related tasks into what Things calls “Areas of Responsibility” – for example I have a categorise for Writing, Personal and Household tasks. You can treat these like open-ended projects, to keep your ToDo lists short and easy to manage. That way you’re not distracted by household chores when you want to review your blog post topics, and vice versa.

Now you should have a list of Next Actions that will include all the single actions plus the first action on each project list, which is hopefully a bit more manageable! You also can potentially trim this list down further by putting off tasks that can’t or won’t be started until a future date, using either the “scheduled date” in your software, or writing a date next to the item.

But what if you still have a long, long list of things to do soon? Never fear – Contexts will help you see the wood for the trees.

Contexts

Another key concept in GTD is Contexts. These are places and situations that determine whether you can do a task or not. For example, when you’re in town you can return those library books but not iron your dress shirt! So you could classify tasks by location such as “Home”, “Town”, “Office” and so on. Or you might need some quiet time in the office to make a phone call, or you might prefer to make all your calls in one session – in either case, a context named “Phone” would help you zero in on this opportunity. Or you might want to organise tasks by the approximate time and/or energy they require (e.g. 5 minutes, an hour), so that you can quickly pick out a short simple task when you have a few minutes on your hands.

Some software programs like OmniFocus have contexts built-in, but in others there may be an alternative way of implementing them; Things, for example, uses tags, which has the advantage that you can tag a task with multiple contexts (that phone call to the cable company, which is likely to leave you on hold for ages, isn’t going to fit into 5 minutes!). Contexts are a bit trickier on paper, but you could use written tags (perhaps in different coloured pens?) or organise non-project tasks in different lists by context.

One general context that I find very useful is “Waiting” – if you can’t move a project forward because, say, you’re waiting to receive an email confirmation, it helps to mark it as such so that it’s off your mental radar. Conversely the “Waiting” context can be used as a quick way to look up all the items you need to chase other people up on.

Conclusion

With all your tasks organised into projects and contexts, you’ll have fast access to your Next Actions and should now easily be able to pick out what you can/should be doing!

Next time: with the day-to-day task management under control, it’s time to look at the Big Picture…

December 31, 2013

GTD for beginners, Part 1

One of the things you get asked a lot, as a writer (after “Where do you get your ideas from?”) is “How do you find time to write?”. The simplest answer is that you have to give up other time-consuming activities: watching TV, playing video games, even—to some extent—reading. But even that will only get you so far if, like me, you are juggling other responsibilities, such as a day job or family. And you still need some time for yourself to recharge your creative batteries, or you’ll burn out.

The big influence on my early adulthood was Shirley Conran’s “Superwoman” (a gift from my mum), which aimed to help the working women of the 1970s keep their lives in balance. As well as specific advice, she had one guiding principle: if you’re going to be lazy, you have to be organised. And being an inherently lazy person, I decided that organisation was my best bet

I’ve tried a few other systems over the years, but the first one that has really worked for me is Getting Things Done (or GTD for short), first described by David Allen in the book of the same name. Being a long-time fan of organisation, I found it easy to implement, but I know (from comments on my blogs) that some people find it daunting – perhaps especially the creative, right-brained people amongst you! So, I thought I’d give my own perspective on GTD, and maybe inspire you to give it a go.

There are really only 3 basic tenets to GTD:

1. Make lists of everything you have to do, ought to do, or might want to do (at some nebulous time in the future).

2. Keep these lists scrupulously up-to-date and complete. If you don’t track these things, they will lurk in the back of your mind, causing you niggling stress.

3. Maintain a strict separation between the tasks that actually need doing, and the material you might need to refer to at some point in the future.

Given these basic principles, the trick to successful GTD is to develop a system that works for you. You’ll find lots of suggestions, in the GTD book and online, of methods you could use, but ultimately it doesn’t matter as long as your system allows you to follow the GTD basics.

Whilst keeping lists is important, the maintenance of them is vital to good GTD, so I’ll address this point first.

Buckets

The crucial first step in GTD is capturing all incoming tasks and information in an efficient way. Allen calls the tools you use to do this “buckets”, as they are intended to be simple, temporary containers.

One notebook is enough! (Photo: Mhairi Simpson)

One notebook is enough! (Photo: Mhairi Simpson)At a bare minimum you will need two buckets: a physical inbox for collecting snail-mail and other small objects that need your attention, and some kind of notepad (paper or electronic) in which to jot down all the to-dos and ideas that cross your mind. The physical inbox is naturally going to be confined to a single location (perhaps near the front door, though I keep mine in my home office), and the “notepad” should ideally be something small that you can keep with you at all times (e.g. a smartphone, or a small notebook and pen). Armed with the latter, you can soon get into the habit of recording thoughts as soon as they cross your mind, instead of having to carry them around until you get back to your desk. Hence it’s important to choose a method that doesn’t discourage you from doing so. If you tend to lose pens, maybe a smartphone is the best choice of bucket; if you find technology fiddly, don’t be ashamed to resort to paper and pen! Make it easy and fun, by choosing a stylish notepad or a cool new app – whatever increases the chance of you actually using it.

I prefer to have a combination of the two: a small spiral-bound notebook for shopping lists, and a notepad app on my iPhone for everything else. The reason for this is simple: I once dropped my Palm organiser in the supermarket and shattered the screen! Also, if my husband volunteers to go to the supermarket alone so that I can get on with my writing (he’s such a dear!), I can tear out a grocery list and give it to him. OK, so many apps allow you to email a note to someone, but unless your other half is also a GTD addict, it can get a little fiddly at that point.

On the iPhone I put new items straight into a GTD-friendly organisation app (of which more later), but for now you can just use your smartphone’s built-in ToDo list. Remember, keep it simple!

Making it happen

Your task this week is to set up your buckets.

1. If you already have an in-tray, empty its contents into a box, carrier bag or whatever – we’ll deal with that stuff next time. If you don’t have an in-tray, find or buy something suitable. It doesn’t have to be a formal office in-tray – any box or basket will do, as long as it’s big enough to hold about a week’s snail mail. Either way, all new mail and small items that need dealing with should go straight into it, the moment they cross your desk or drop through your letter-box.

2. Decide what kind of notetaking bucket suits you best – electronic or paper. If paper, buy a notebook and pen small enough to carry around with you everywhere. If electronic, either install a new notepad app on your device or, if you already have a favourite, back up its contents, delete them from the app and start using it only for GTD. (Or use both – but only if, like me, you have a clear separation of purpose.)

3. Get into the habit of jotting down every reminder that crosses your mind, the moment it does so (or as soon as you can). If you record it straight away, that’s the first step in ensuring it gets done.

Next week we’ll look at how to organise this amorphous mass of ToDos into a neat structure so that you don’t feel overwhelmed.

Happy organising!