Constructed languages in fantasy & SF

A couple of years ago I blogged about how I’d gone about creating the languages for my alternate history fantasy series Night’s Masque. At the time, The Alchemist of Souls was undergoing final edits, so I felt it was a bit early to post any details of the languages. However, this month being the fortieth anniversary of the death of J R R Tolkien, I felt it was high time I did a new series of blog posts on the topic of conlangs (constructed languages).

In this first post, I’m going to cover the history of conlanging in SFF. In following weeks I’ll talk about how you might go about creating your own language, and finish up with some software tools that can help you with the task.

A Brief History of Constructed Languages

Conlangs existed well before Tolkien came along, of course. Probably the most famous is Esperanto, created in the late nineteenth century by the Polish doctor and linguist L L Zamenhof, though there are examples dating back much earlier. Most of these invented languages were intended to have practical applications: they included attempts to reconstruct the language of Adam and Eve and to develop a “perfect” language (according to various criteria), or were used for cryptography.

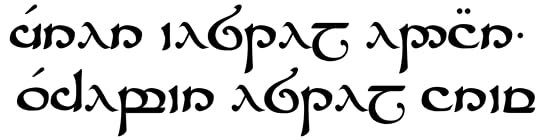

Tengwar (Sindarin script) by Xander, Wikimedia Commons

Tengwar (Sindarin script) by Xander, Wikimedia CommonsFor Tolkien, on the other hand, language-making was simply a hobby. He loved languages and wanted to make his own, just as SFF writers love to invent worlds. But whereas most modern writers start with a world and then create a language for it, Tolkien started with the languages and then wrote stories to give them a context. He even went so far as to create elegant scripts to write them in.

Whatever the reason, the languages gave his books a depth of verisimilitude that few have achieved before or since, and as with his fiction, there have been many imitators of this aspect of his worldbuilding. Before Tolkien (and, regrettably, after in some cases), invented names in SFF leaned towards the unpronounceable, such as H P Lovecraft’s Cxaxukluth and Xa’ligha. The apostrophe is particularly heavily overused;TV Tropes refers to this practice as the Punctuation Shaker. Even when there’s some kind of reason or consistency behind it (as with Anne McCaffrey’s dragon-riders, who shorten their names when they bond with a dragon to denote their change in status), the poor apostrophe has become such a mark of bad worldbuilding that many readers will run screaming at the sight of it!

After Tolkien’s elvish languages, the most famous conlang is probably Klingon, created by actor James Doohan for Star Trek: the Motion Picture and developed in detail by linguist Marc Okrand. So popular has it become that there is now a Klingon Language Institute that produces learning materials and translations of Earth literature and supports a community of conlang fans.

In recent years, the growth of the internet has enable the easy sharing of resources on basic linguistics, which has led to a better quality of conlangs. One of the pioneers of this new generation of conlangers is Mark Rosenfeld, a comics fan and linguist whose website has hosted The Language Construction Kit since 1996. (I’ll talk some more about the LCK next week, when we come to how to create your own language). At the same time, the use of Tolkien’s invented languages in the movie adaptations of The Lord of the Rings has exposed a whole new audience to the idea of language creation.

At WorldCon in Chicago last year, I was lucky enough to be invited onto a panel with both Lawrence Schoen, the founder of the KLI, and David Peterson, an American linguist and president of the Language Creation Society, who is best known for creating the Dothraki language for the TV series Game of Thrones. As far as I know, George R R Martin’s books feature Dothraki names but no actual examples of their language. However HBO decided to give them a language to speak on-screen that could then be subtitled, perhaps to emphasise their foreignness. They brought in Peterson as a consultant, and he has since gone on to create High Valyrian for the same show as well as the alien languages Castithan and Irathient for Syfy’s near-future SF series Defiance. If you’re interested in his work, you can find a number of websites online via his blog or follow him on Twitter, where he’s @dedalvs.

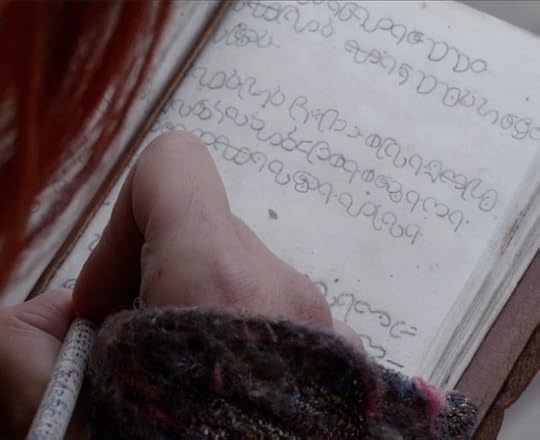

Irisa’s diary, from TV series Defiance

Irisa’s diary, from TV series DefianceI suspect that the popularity of these TV conlangs arises from the fact that you can hear the characters speaking them, rather than just seeing them written down on the page. That’s a big disadvantage to novelists, though with the growing popularity of audiobooks, perhaps there will be a resurgence of interest in constructed languages in books. When I created the skrayling languages used in Night’s Masque, I took particular care to make them pronounceable by an Anglophone reader, partly because I knew that Angry Robot had a new strategy of releasing audiobooks simultaneously with print formats so I knew they were destined to be read aloud. Fortunately I was assigned an excellent narrator, Michael Page, who managed to pronounce most of the examples of skrayling speech pretty accurately, and sometimes even better than I could manage! (I have no problem with fricatives in things like the Scottish place name Auchtermuchty, but can’t roll my ‘r’ sounds for toffee.)

That concludes my whistlestop tour of the history of conlangs. Next week: how to do it yourself!