Khoi Vinh's Blog, page 187

February 16, 2011

TD 63-73

Boutique design publisher Unit Editions have announced their latest book: "TD 63-73: Total Design and Its Pioneering Role in Graphic Design." An "insider's account" of one of the more influential design studios from the height of mid-century graphic design.

"Written by Ben Bos, a key member of the studio, the book describes how a group of idealistic Dutch designers came together to form a multidisciplinary design studio that helped shape the future of graphic design. Total Design began in Amsterdam in 1963. Ben Bos joined the founders (Wim Crouwel, Benno Wissing, Friso Kramer and the Schwarz Brothers) from the outset. Together, and individually, they set new benchmarks for identity design, cultural design, exhibition design and product design."

Preview images look very promising, and the cover is gorgeous.

Pre-orders will receive free international shipping (the book is sold from the U.K., where Unit is based). Of course, ordering means figuring out the company's Web site, which is just good enough that it really should be much more usable and better designed than it is. Start deciphering the ordering process here.

February 15, 2011

Fast Co.: User-Led Innovation Can't Create Breakthroughs

Apple and Ikea demonstrate that user-centric design is a fallacy, argues this opinion column by design professional Jens Martin Skibsted. He insists that "user insights can't predict future demand," "user-centered processes stifles creativity," and that "user focus makes companies miss out on disruptive innovations." He also (anonymously) quotes members of the Apple design team regarding their view of user-centric design:

"It's all bullshit and hot air created to sell consulting projects and to give insecure managers a false sense of security. At Apple, we don't waste our time asking users, we build our brand through creating great products we believe people will love."

This is a healthy debate within the design profession. I hope it becomes a bigger and bigger debate, too. Read the full piece here.

Confirmed: Blu-Ray Not for Moms

When I was visiting my mother earlier in the month, I helped her upgrade her 'home theater' — I hesitate to call it that because her needs are not nearly so grand as replicating a theater viewing experience inside of her home. She just likes to watch the occasional movie and maybe tap into her granddaughter's Flickr stream and that's about it.

She had an old 30-in. CRT television that weighed about a ton, but I managed to kick it to the curb and bought her a new, inexpensive Vizio LCD television. Setup was a breeze, but of course her old DVD player was not capable of upconverting to the new TV's greater resolution, so playing movies looked terrible on it. I went to the store with the idea of buying her a new, simple, US$50 upconverting DVD player.

Fool Me Twice, Shame on Me

Somewhere along the way though, I was distracted by a good price on a Sony Blu-Ray player, this in spite of my previously documented poor experiences with Blu-Ray. I know, I should̵ve known better, but I decided to give the format another chance, reasoning that it would let my mother take full advantage of her new TV. Like most Blu-Ray players, this one could access Netflix and other online video and music services, so I figured at US$160, it was a decent deal. I bought it, brought it home and set it up for her. Blu-Ray discs looked wonderful on it.

Then I realized that the device was actually only Internet-capable, that in order to access anything on the network at all, to say nothing of Netflix, the additional purchase of a Wi-Fi dongle was necessary. Unfortunately, the only dongle that works with that player costs US$80 dollars — that's half the cost of the unit just to attach a USB Wi-Fi card to the back of the unit — bringing the total price of the unit up to US$240.

The next day I returned the Blu-Ray player and bought a simple DVD player instead, plus an Apple TV for US$99. Everything worked great out of the box, no additional gadgets necessary, plus now she has the full breadth of content that an Apple TV provides in addition to Netflix, all with a mom-friendly user interface. Of course, she can't watch Blu-Ray discs but, having now fully learned my lesson regarding how customer-hostile the format is, I figure she's better off without it.

February 14, 2011

Music at the Speed of Hype

A few weeks ago, fan site Radiohead At Ease — among other sources — reported on an unsubstantiated rumor that Radiohead's long-awaited eighth album was already complete. Then, this morning, the Internet woke up to find that apparently the album is finished after all and fans can pre-order it immediately. Physical copies of the new record won't be available for a few months, but the songs will be available for download this Saturday. Wow.

This is the way music works in the 21st Century: no waiting through months and months of unconfirmed deadlines, no release dates announced several quarters in advance, no slogging through interminable marketing campaigns trying to build up anticipation, no manufacturing timelines holding up the delivery of the songs, no record companies just generally getting in the way. When the music's done, it ships. This will soon be the norm for record releases but at the moment it still strikes me as kind of amazing. Now, if the band could just finish recording their records a bit more quickly, we'd really be living in the future.

MORE/REAL Stylus Cap

Depending on whether you think a stylus tool would make for a much needed complement to your iPad or a heretical corruption of its original idea, you may or may not like industrial designer Don Lehman's new Kickstarter project: The MORE/REAL Stylus Cap attaches to either end of standard-issue Sharpie markers, Bic ballpoints or Pilot Fineliner pens, giving users greater precision for sketching and drawing.

Find out more and pledge at the Kickstarter page.

February 11, 2011

Where Did the Korean Greengrocers Go

Over at the urban-policy magazine City Journal, writer Laura Vanderkam takes a fascinating look at the shifts in economics and immigration that led Koreans to dominate the greengrocer industry in New York City for a generation and then, almost as quickly, start to leave it behind. Read the full article here.

This brings to mind two related projects. First is Virginie-Alvine Perrette's little-seen 2008 documentary "Twilight Becomes Night," a look at the dwindling number of independent, neighborhood-oriented businesses in New York. Second is the more popular coffee table-sized book "Storefront: The Disappearing Face of New York," which photographs the same phenomenon, beautifully capturing some of the mom and pop shops remaining throughout New York's five boroughs. (It's a huge book, but also recently made available in a smaller format.

February 10, 2011

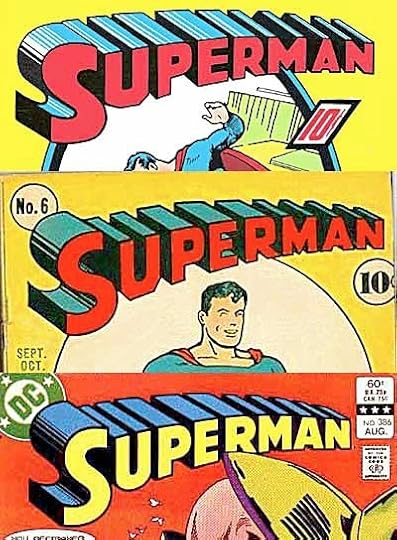

Comics' Greatest Logos

Veteran comic book letterer and type designer assembled this list of the "greatest" comic book logos in history. The intention was to identify the marks that "have had the greatest impact, are instantly recognizable and have withstood the test of time." There aren't a lot of surprises here, but the list really does show how iconic many of these logos have become, how deeply ingrained into our collective pop cultural memory they are.

It's not just a list, either. Klein, whose grasp of the typographic history of comics probably has very few peers, identifies the designer of each logo and each logo's various iterations. Fascinating stuff — well, to me at least. See the whole list here

An Archive for Interaction Design

Designers are terrible at saving what we do. Most of us know that we should take the time to document what we've done for our own portfolios, if not for posterity. Yet few of us take the trouble. We usually wait until we leave our jobs and a portfolio becomes an imperative, or when a potential client spurs us to write a case study of a finished project.

In the analog world, this is merely an inconvenience. We scramble to dig up old mock-ups, assets, tearsheets, samples, and digital files. It's tedious, but the definitive nature of analog design — the fact that there's a canonical version of every brochure or book jacket — makes the archival process a straightforward one.

Archiving digital design, on the other hand, is far less clear-cut. It's been said before, but it's worth repeating that digital media is a conversation. To design for digital media is to design systems within which wildly varying kinds of interactions can happen, virtual systems that are conducive to great conversations. Conversations, however, are notoriously difficult to fully capture.

Saving Conversations for PosterityImagine a verbal conversation between two or more people and consider the methods available for documenting it. You could transcribe the words spoken, of course, but those words are just one aspect of communication. Missing in that transcription would be a record of the the subtleties of the exchange, the pauses, the awkward moments, the sudden and spontaneous laughter or insight, and the facial expressions and hand gestures that do so much to flavor any exchange.

Even if you could capture those intangibles, the record would only be documenting the content, not the environment around it. Perhaps the conversation takes place at a formal event, like a gala or a dinner banquet. You could capture the invitations and other collateral, but those tell us very little about the event itself. Photography and film or video could capture scenes from the evening as well, but these measures require significant expertise, and their end products are frequently biased.

This hypothetical conversation is very similar to the challenge we face when we think about archiving digital design. More and more, digital media is social by nature. Designers are creating event-like structures within which robust conversations take place, with at least one added layer of complexity: The events don't end at midnight. They go on and on and on. Digital media is a conversation that has no end, a conversation that changes constantly. And as an industry, our attempts at archiving digital design have been less than satisfactory.

There's no shortage of printed compendia of digital design, books that are full of page after page of screen grabs from websites, arranged like a binder of mug shots. While these may satisfy some people, there are few serious digital designers who refer to them. Design competitions, similarly, will curate a selection of the best digital design within a given time frame, but they do such a poor job of surveying the entire field that their relevance to professional digital designers is minimal at best. Archive.org's venerable Wayback Machine, which seeks to capture snapshots, in code, of sites across the Internet, is valuable; yet it fails to catalog the images on any given web page. If the original site has taken down the available image, it's lost forever.

Just as a mere transcript of a conversation will never be enough to accurately record all of the detailed nuances of an exchange, this method is incomplete. But you can hardly place the blame on the good folks at Archive.org. They are years, if not decades, ahead of most of us on this problem, and designers, with our limited enthusiasm for the act of archiving, have been particularly neglectful. The Internet changes radically every three years, if not sooner, and yet we have very little record of the major role that we've played in its upheavals.

The problem is only becoming more difficult. Even if we could capture the full experience of the web, digital design is expanding beyond the relatively discrete confines of a "Web site." The total experience of visiting Facebook isn't just the site you see at Facebook.com, but also the countless sites that serve up Facebook's widgets every day. Likewise, Twitter is barely represented by Twitter.com, as most users access the service through third-party clients like TweetDeck and Echofon, or on apps installed on their smart phones. Location-based network applications such as Foursquare and Gowalla reside almost entirely on mobile devices, which requires roaming in the real world in order to be fully experienced. It's impossible to capture the entirety of these experiences.

The real question is, what do we want to save, and for what purpose? Do we need to merely document the typical interactions within a digital design, so that the most salient aspects of today's Facebooks and Twitters make it into future history (e-)books relatively intact? Or do we need to take an architectural approach and try to preserve designed online spaces, so that students of history can themselves be immersed in the experiences as they exist today?

Similarly, is it enough to capture code to be compatible with tomorrow's technology, so that today's designs can be run on tomorrow's hardware? Or do we need to record and recreate the hardware properties that render today's digital experiences? Will it be useful to experience YouTube on the inevitably faster technology that will become available in the future, or do we need to reproduce the joy and pain of waiting for movies to buffer on 2010 hardware over 2010 broadband?

These and many more unanswered questions represent the downside of digital media's inventiveness; it's changing so fast none of us has time to think about how to preserve its most instructive lessons. But we can't afford to ignore these issues for much longer. Today, we have no best practices for archiving digital design for the future, largely because we have yet to really grapple with these questions. Meanwhile, major milestones in digital design are being lost every year. Every time a site or an application gets a major upgrade, every time an interface is overhauled, it represents something learned, knowledge accrued to advance the craft. But we won't benefit easily from these revelations if we don't do the hard work of archiving these steps forward.

This article was originally published in the October 2010 issue of Print Magazine as "Toward an Archive of Digital Design." Read more of my writings for Print here.

Uncommon Cures for the Common Cold

I was thinking about medicines this morning. As I've complained before, it's been a terrible winter and so I'm fending off what seems like the fourth or fifth cold of the season already (having a toddler who brings home germs from play groups is part of this too).

My medicine cabinet is full of open boxes of cold remedies like Cold-Eeze, Zycam, Robitussin and others. Most of these over-the-counter medicines would taste neutral, bitter or worse were it not for the window-dressing of artificial flavorings like cherry, citrus or that generic, unidentifiable kind of sweetness you might associate with Smarties and other completely unnatural candies. Similarly, they're all far too sweet for my taste; almost all of them make me a little nauseous.

Part of the reason for this of course is that it's probably unwise, for obvious concerns, to make medicines so tasty that you look forward to the next dose. Still, it seems possible to me to create a sub-class of cold remedies that have more subtle, less powerful flavorings. I'd probably buy a cough syrup that tastes like some kind of lightly sweetened tea, for example, or a throat lozenge that has the flavor of rice candy, or a zinc supplement that comes in butterscotch. These could and probably should still taste a little bit unpleasant, but they don't need to be as brutally sugary as they are now.

You Are What You Sneeze

This is all a bit off topic for this blog, I know, but there is some connection to design here. Nearly all of the basic goods we consume now exist in some more specialized, more eclectic and yes more expensive form. There are artisinal cheeses, organic breakfast cereals, grass-fed beef, raw milk, and many more bobo alternatives to the basic stuff our parents used to buy unquestioningly.

This trend has a lot in common with the rise in prominence of design over the past decade or two; it's intimately linked with our increasing interest in consuming things that are more sophisticated and more elitist. I think we have to recognize that in large part design is about enabling more conspicuous, self-congratulatory forms of consumption, and while sophisticated foods are not strictly a form of design, they are complementary to the designed lifestyle that many of us aspire to, and that many of us promote. I'm not implying a value judgment here, because I am clearly in the target demographic for a lot of these goods. I'm just remarking that it can be striking when a whole category of goods like medicines is omitted from that kind of thinking; it just makes me think that it's only a matter of time before I can buy a bottle of organic, Napoleon cherry-flavored NyQuil. And I'll probably buy it, too.

February 8, 2011

10 Answers

New York designer and writer Rebecca Silver recently started this site where she posts a Q & A with a creative professional every day, posing the same ten questions to each. She's had some terrific gets already, including George Lois and Ellen Lupton, as well as some great up-and-comers like August Heffner. Visit the site here.

Khoi Vinh's Blog

- Khoi Vinh's profile

- 5 followers