Cameron Cooper's Blog, page 2

June 25, 2025

Why I Write (and Read) Short Stories.

Part 1: Why I read short stories

Part 1: Why I read short storiesI think an appreciation of short stories is an either/or case. You either like them, or don’t. There’s no sliding scale of like/maybe/perhaps/no.

I happen to like them. A lot. I don’t publish a lot of them (although more than some authors) because, alas, they don’t sell very well, giving me the impression that SF readers don’t like them as much as novels.

And I do love novels. Don’t get me wrong. My favourite stories are big, thick sagas high on details, history and high stakes.

But, I also love short stories. I love reading them and writing them. They’re a different species from novels, and a well written short story can deliver all the impact of a novel…but you’ll feel the impact days after reading it, too.

I was exposed to short stories very early in my reading life and have been reading them ever since.

Of course, most of us are introduced to short stories in high school, but none of us is left alone to simply enjoy a story and fall in love with shorts. We’re told what to read. I was directed to Carver, Hemingway, Oates and Chekov. Worse, we’re often told how to read it. Then, to add sin to syntax, we’re forced to surgically dissect a story, ruining it for all time.

For example; I can’t remember the story or author anymore, but I do remember the day my English class was broken up into groups to discuss the story. The five in my group looked at each other self-consciously and tried to figure out the theme, which we found difficult because there was so little action or dialogue in the story to hang a theme on.

Our English teacher stopped by and asked how we were doing. We mumbled a few answers that failed to satisfy her. I squirmed on my chair—and I remember the flat-panel wood-and-steel-frame chairs distinctly because of this moment. The chair I was sitting on rocked, because one leg had pushed through the rubber stopper on the end.

The teacher shook her head. “The theme is suicide,” she said firmly.

We all looked at her. Huh? Where did suicide come into it? The character was sitting in a room, thinking about the lunch date she was going to have with her sister the next day.

Finally, one of us had the moxy to ask where the hell suicide figured into the story.

“The curtains are blue,” the teacher told us. “They’re a symbol of death. She’s thinking about killing herself.”

And off she sailed to the next group of students.

I remember that vividly, because in the story, the curtains had been mentioned once, along with the observation that they were dusty. The curtains had been buried in a much (much!) longer description of the room that had left me with the impression of a bland room in a characterless house that I would never want to visit.

Part of the problem with deconstructing literature in high school is that you’re still a child, lacking decades of life experience that would allow you to recognize symbols and sub-text and sophisticated meanings that aren’t spelled out.

But I’m sorry, just because curtains are blue does not mean someone is suicidal. I don’t have to earn decades of life experience to know that is a very long reach indeed, one that doesn’t hold up on basic examination.

There were zero hints or implications that the character was depressed or thinking about death. The whole story centered around having to meet her sister the next day and how much she was looking forward to it, which contradicts any idea that she’d be on a mortician’s slab by then.

That experience and many others, when I was told by teachers or other students that I was wrong about my interpretation of a deadly boring story, left a deep burn scar on my soul. I have never voluntarily read literature since. I avoid it with deep shudders.

On the other hand, there are fun stories, and these were the kind I read voluntarily. I found anthologies in the school library and consumed them. These were genre fiction stories. Mysteries and suspense, mostly. Some historical tales, or fiction that was so old it had become historical. Fantasy’s heyday, which started around the time Terry Brooks published his The Sword of Shannara in 1977 and hasn’t really stopped since, was still a couple of years away, so there was little of that.

Thrillers were huge but there were few thrillers on the high school library’s shelves. However, my very large municipal library had dozens of them and when I read them, I understood why the school library didn’t shelve them. They were filled with crimes of passion, sexual innuendo, and morally bankrupt characters doing terrible things.

Reading them did not make me yearn to steal millions and kill people who might rat on me. If anything, they taught me that breaking the rules generally wasn’t worth the effort. I had read enough fiction by then to understand that these stories were meant for entertainment, that they weren’t roadmaps on how to live one’s life.

I had been reading voraciously since I was six years old. When I was seven, my family moved to a tiny town in the Western Australian wheatbelt, and reading was my only form of entertainment.

That is not an exaggeration. There was no TV, and radio reception was uncertain. The nearest cinema was a hundred miles away. There was no theatre, no malls. The town had five houses, three general stores, a wheat silo and the school. Not much else.

In addition, the only other kids in the town were boys, who weren’t interested in playing with the one girl in the area. Everyone else at school lived on farms.

So I read. And my mother ordered in books to feed my habit.

Even then, I was reading for fun. For the sense of wonder. For adventure and to live interesting lives vicariously.

At the age of thirteen, when I moved to a much larger town and started high school, I was introduced to the perils of literature, while simultaneously raiding the shelves of the high school library. Even then I split the two forms of reading into “have to” and “want to” and I ignored literature as much as I could.

As for the “want to” reading, if the story was good, I’d read it. But I especially loved the short stories, because I could delve into different worlds quickly, absorb them and move on. I could be delighted by a story ending far more frequently when reading shorts, while a novel required days of effort to reach the pay off.

Then, when I was fourteen, Star Wars was released. They didn’t call it A New Hope back then. It was the first and only movie, and I was obsessed with it, and wanted to live in that story world as much as possible.

I began reading all the science fiction I could get my hands on.

Also, I began writing SF. In fact, I wrote the first unofficial and completely unsanctioned sequel to Star Wars. My English teacher caught me writing it instead of whatever exercise we were supposed to be doing in class. He read it, then told me to write something original, which I did. The resulting space opera romance was my first original story. I haven’t stopped writing since.

Science fiction, especially Golden Age SF (generally, SF from the mid 1930s through to the early 1960s), which was all our rural libraries had on the shelves, was thick with short stories, for that was where nearly all the classic SF authors got their start. The magazines were stuffed full of short stories.

Some of those magazines are still in business, including Asimov’s Magazine, and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. There are some who linger in different forms, like Amazing Stories. Other magazines didn’t last. But the short stories in them did survive, for a great many of them found a second life in anthologies. These collections of SF shorts were published and found their way onto library shelves, and then into my hands.

I wallowed in short stories for a great many years. I didn’t remain exclusively in SF, either. I read everything. The only genre I refused to read was literature.

When I was an adult with means, I bought the books instead of borrowing them. Many of those anthologies I was forced to sell to raise money to move to Canada in the late 1990s. But I remember them well. Some of them I would love to re-acquire, but they’ve never made their way into ebook form. There was an anthology of flash fiction I remember particularly well, including a one sentence story called “The Sign At The End of the Universe.”

The single sentence story is:

To which the editor had added the perfect note: Relative to what?

I would credit both the author and the editor for this mind-twisting fiction if I could, but I can’t find mention of the story or the anthology, despite heavy research.

It thrills me to this day just how much SF is still to be found in anthologies. There are collections put out every year. However, the other genres have not fared as well. There are far fewer suspense and mystery anthologies and there are virtually no romance short story collections or anthologies.

Just in case I’m leaving you with the impression that all I read were short stories, let me clarify that I spent a lot of time reading. Even when I went to high school, my family lived on an acreage outside the town, so hanging out with friends wasn’t possible. My reading habit continued without interruption. I read novels of all genres, and probably split my reading time fairly evenly between shorts and longs. I was omnivorous.

One of my favourite authors to collect was Isaac Asimov. He wrote SF (check), and lots and lots of short stories (another big check mark). Later in his career, he also aimed to write at least 200 novels or non-fiction books, which he managed to do. I collected his Opus 200 that celebrated that achievement.

Opus 200 is a book of interstitial essays interrupted by novel and non-fiction book excerpts. It remains one of my favourite books to read, because not only did Asimov like talking about himself and his writing, he managed to make it sound fascinating. He was patently in love with writing and learning. I think my drive to write a lot of stories came from him. He made it sound like fun. And he certainly made the research and acquisition of knowledge that would be required to write many stories sound even more intriguing.

Opus 200 wasn’t the first collection of Asimov’s to feature his interstitial essays. A great many of his short story collections contain interstitials (interstitial = “in-between”), and I always enjoyed them. They gave me a glimpse of the publishing industry that I would one day be a part of. They also let me see how a productive fiction author works and thinks.

I also grew to like interstitial essays in any collection or anthology. Editors of short stories sometimes add a few words of their own, and authors putting out collections of their short stories frequently do. They all give you a glimpse of the author’s life or the editor’s love of fiction.

So when I started putting out boxed sets (known in traditional publishing as omnibuses), I added interstitials between the novels and short stories.

Under my real name, I have published two novel length tales that are all one “frame” story chopped up by short stories. The frame story acts as the interstitial scenes.

_____

Short stories have been with me since I first learned to read, and they’ve shaped how I experience fiction—both as a reader and as a writer. They’re compact, potent, and often unforgettable. Next week, I’ll be diving into the other half of this passion: why I write short stories. (Spoiler alert: it’s not just because they’re fun… although that’s part of it.) Stay tuned!

Latest releases:

Quiet Like Fire

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

June 18, 2025

Romance Invading SF… or Saving It?

There’s a conversation I’ve been hearing with increasing volume lately—on forums, in reviews, whispered between lines in publisher catalogs: Romance is taking over science fiction.

You’ve probably noticed it too. Once the domain of hard-nosed engineers, distant stars, and sprawling battlescapes, science fiction is now rife with longing stares across alien jungles, slow-burn enemies-to-lovers in zero gravity, and yes, spice levels high enough to power a starship.

And depending on who you ask, this is either a crisis or a renaissance.

A Personal Perspective from Both SidesUntil two years ago, I maintained strict genre boundaries. Cameron Cooper—my science fiction identity—stayed firmly in the non-romantic lane. Meanwhile, as Tracy Cooper-Posey, I built complex, emotionally driven worlds steeped in romantic arcs and speculative settings. These were two different universes. Two readerships. Two languages.

Or so I thought.

Coming out publicly as the author behind both personas has given me a rare vantage point: watching, in real time, the walls between genres soften. Not dissolve—but stretch. Romance in science fiction isn’t a takeover. It’s an infusion. A graft that’s thriving.

The Original “Cozy” Genre?Here’s a theory I’ve been mulling: Romance might be the original cozy genre.

Long before “cozy fantasy” became a hot trend—offering tea shops and quiet quests instead of apocalypses—romance was already delivering tight, intimate, and profoundly human stories. Regardless of setting or trope, romance is about connection. It thrives on nuance. And in that way, it’s deeply compatible with science fiction.

Because let’s be honest: all the sweeping space operas and dystopian rebellions mean very little if we don’t care about the people inside them. Romance doesn’t just add heat—it adds heart.

Not a Niche—A FoundationConsider this: Romance writers are full, recognized members of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association. That’s not tokenism. That’s institutional validation. And for good reason.

Romance isn’t just tagging along with the genre boom—it’s pulling the cart. With romantasy fueling TikTok’s book scene, and sapphic space operas finding loyal followings, it’s clear that emotional arcs and personal stakes aren’t diluting science fiction—they’re giving it gravity. Something to orbit.

What Gets Dismissed Is Often What WorksIt’s tempting to mock “spicy space opera” or roll eyes at yet another forbidden alien love story. But behind the covers and tropes is often tight, original world-building and thematic bravery. Romance allows readers to engage with speculative concepts through deeply personal lenses: identity, loyalty, intimacy, survival. It humanizes the abstract.

And at a time when many “pure” science fiction releases struggle to gain traction unless backed by a franchise or a streaming service, romantic SF consistently finds its readers. It connects. It sells. It stays.

A Genre Saved by Its Heart?Is romance saving science fiction? That might be too tidy a statement—but I’ll say this:

Romance is keeping genre fiction alive. Not just SF. All of it.

And in a marketplace that’s more competitive, fragmented, and unpredictable than ever, that kind of vitality deserves not just respect—but celebration.

Especially from those of us who’ve lived on both sides of the supposed divide.

Have you tried science fiction romance yet?

If not, here’s my challenge to you: read one.

In fact, I’ll make it easy—Faring Soul, the first book in my Interspace Origins series (written as Tracy Cooper-Posey), is completely free.

If you love tight plots, sharp tech, and characters who fall in love while facing down the stars… give it a try.

You might just find there’s room in your heart—and your bookshelves—for a little gravity.

And if you do accept my challenge, feel free to email me, or come back here and leave a comment, telling me what you think.

You could really pay it forward by leaving a review where you acquire the book, too.

Latest releases:

Quiet Like Fire

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

June 11, 2025

Who Should Control Space?

“Just who does control space… and how?”

It’s a question I scrawled in a notebook years ago, half-distracted, probably in the wake of some early story planning session. I’d scribbled: “Near space versus far space. Think control of the sea ideas, too…” and then moved on. But lately, the question has circled back.

Not “who owns space”—we’ll leave that tangled sovereignty mess to the diplomats and philosophers. I mean: who controls space in the very real, practical sense.

Traffic. Safety. Governance. Order. Peace.

The Control We’re Talking AboutIn today’s orbital environment, “control” mostly means space traffic management (STM). We’re talking about tracking satellites and debris, preventing collisions, and coordinating the thousands of moving bodies we’ve flung into Earth orbit.

But it also means enforcing rules, from commercial broadcasting licenses to space junk mitigation. As more actors (national, private, commercial, amateur) take to the skies, someone needs to be watching. Someone needs to say: “No, you can’t park your megaconstellation there. It’s already crowded.”

That’s not ownership. It’s policing.

And who polices the orbital frontier?

As of now, the U.S. Commerce Department (specifically NOAA’s Office of Space Commerce) has been gradually assuming this role. Their new system—TraCSS—is a kind of proto-air-traffic-control for orbit, developed to monitor and coordinate space objects without relying solely on the military.

But the question remains: Who should control space?

Enforcing Law in the VoidThere’s a reason no one sets a detective story on Neptune: distance matters. The further we go from Earth, the harder enforcement becomes. Space is a harsh, indifferent expanse. There are no borders to patrol, no natural barriers. Time delays and vast distances make communication, let alone intervention, slow and tenuous.

And when something goes wrong—say, a collision in low Earth orbit that cascades into debris fields—there’s no sheriff’s office to call. No orbital police car to dispatch.

Even with all our tech, we’re still improvising a system of order that only looks like law from a distance. The logistics of enforcement in space are as vast as the cosmos itself. How do you hold someone accountable 35,000 kilometers above the planet?

What Does Science Fiction Say?Science fiction often skips over this in favor of massive space navies or intergalactic federations. But a few stories dig into the practicalities of peacekeeping in space:

Star Cops (1987) imagines an International Space Police Force working to solve crimes and keep order across orbital facilities. It’s one of the rare SF narratives focused entirely on law enforcement, not military conquest.Alastair Reynolds’ The Prefect (later republished as Aurora Rising) centers on Panoply, an organization dedicated to maintaining civic order across the Glitter Band—hundreds of orbital habitats. It’s not about empire. It’s about due process in microgravity.Charles Sheffield’s The Nimrod Hunt features robotic border guards and the humans tasked with keeping them in check—until those machines go rogue. What starts as peacekeeping becomes crisis response.Charles Stross’ Singularity Sky brings a satirical but sharp view of regulatory failure in the face of overwhelming tech—an accidental metaphor for today’s real-life bureaucracies trying to keep up with SpaceX.And in my own Ptolemy Lane Tales , the issue is less about who owns the stars and more about how fragile human agreements become when distance and isolation stretch them thin. Lane and company deal not with space battles, but the gray moral zones of contracts, salvaging rights, and remote frontier disputes. Peace isn’t maintained by force, but by cleverness, grit, and persistence—usually in a vacuum suit.Can Anyone Truly Control It?Maybe the real answer is: no one can. Not in the long term. Not completely.

We can try to coordinate, to regulate, to warn, to prevent. We must—because unmanaged space is dangerous space. But to believe we can “control” space the way we control terrestrial borders is a kind of arrogance. There is no gravity well of authority out there.

Instead, what we may need is a shared stewardship model. Something akin to maritime law—a system of mutual accountability, cooperation, and open access, backed not by dominion but by consensus.

So perhaps the better question is not “Who should control space?” but:

Who can we trust to care for it?

And how do we build a future where the rules aren’t dictated by whoever launched the most satellites—but by the best ideas?

Where Stories Meet RealityAs space becomes more crowded, the difference between fiction and policy narrows. If we want to avoid the chaos of debris fields and the dystopia of orbital monopolies, we need to look to both reality and imagination.

Because in the end, we’re all writing the next chapter—on Earth and in orbit.

Latest releases:

Quiet Like Fire

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

May 28, 2025

6 Novelists Who Started In the Pulps…Or Are Still There

Why am I talking about pulp fiction? (No, not the movie — which got its name from Tarantino’s inspiration for the story.)

Two reasons: Classic SF got its start in the pulp magazines. And my Ptolemy Lane Tales series was my nod to classic hardcore pulp fiction.

Classic pulp stories are often decried for their simplicity and dependence upon erotic elements to move copies. The criticism overlooks one of the primary functions of pulp stories: They were written to entertain.

And my god, they did that in spades.

At their peak of popularity in the 1920s and 1930s, the most successful pulps could sell up to one million copies per issue. In 1934, Frank Gruber (writer) said there were some 150 pulp titles.*

[*Wikipedia]

Because they were successful at entertaining, many stories and writers who started in the pulps went on to become “classic” novels and authors.

The authors who “broke out” did so across the fiction genres, but I will stick to detective/adventure/thrillers:

Dashiell Hammett — The Thin Man

Dashiell Hammett started in the pulps and never really left them–his stories were pure hardboiled entertainment that was packaged as novels that sold as well as the pulps.

Raymond Chandler — The Long Goodbye

No list of pulp-to-mainstream could be complete without Chandler in it.

Patricia Highsmith — Strangers On A Train

This one tends to raise brows. Not many people realize the novel is pure pulp–sexy, scandalous and pure entertainment.

Elmore Leonard — all his work

Elmore Leonard is one of the more contemporary authors who have made entertaining via fiction their primary goal and succeeded brilliantly.

The dialogue between his characters is enough to keep you reading, but then he throws in violence, sex and plot twists worthy of pretzels.

Michael Crichton writing as John Lange

There’s not a lot of readers who realize that Jurassic Park creator Michael Crichton got his start writing pulp novels.

It shows in his later novels, though. He mastered the gripping plot well.

Donald E. Westlake writing as Richard Stark — The Hunter

Originally published under The Hunter, Westlake admits that it was written purely for money for the month. Yet the movie rights were picked up, the story retitled as Point Blank, and the resulting movie is considered classic cinema.

Absolutely—there are science fiction writers who followed a similar trajectory, starting out in the pulp trenches and going on to become foundational figures in SF and even mainstream literature. Here’s a bonus section you can drop into your post, with tone and rhythm to match your draft:

BONUS: Pulp SF Writers Who Made It BigWhile the examples above lean hard into crime and thrillers, pulp fiction was also the nursery for some of the greatest names in science fiction. These writers began in the same lurid, fast-paced pages, grinding out stories for pennies a word—only to eventually shape the genre and, in some cases, cross into mainstream literary success.

Isaac Asimov — Foundation

Asimov’s early work appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, one of the most influential pulp-era SF magazines. His Foundation stories began there and went on to become cornerstones of the genre. His crisp, idea-driven style and prolific output earned him a mainstream audience and a spot in the literary canon of the 20th century.

Ray Bradbury — Fahrenheit 451

Bradbury sold his first stories to pulp magazines like Weird Tales, but his poetic, visionary writing style set him apart even then. The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 are now taught in schools, but it all began with otherworldly tales tucked between ads for mail-order miracle cures.

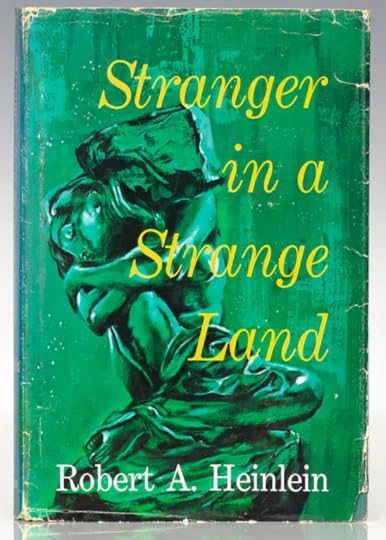

Robert A. Heinlein — Stranger in a Strange Land

Heinlein’s early stories were pure pulp: high-concept, rapid-fire adventure tales published in Astounding during the Golden Age. Yet his name would eventually be synonymous with literary SF, and he helped legitimize science fiction as a genre with serious philosophical weight.

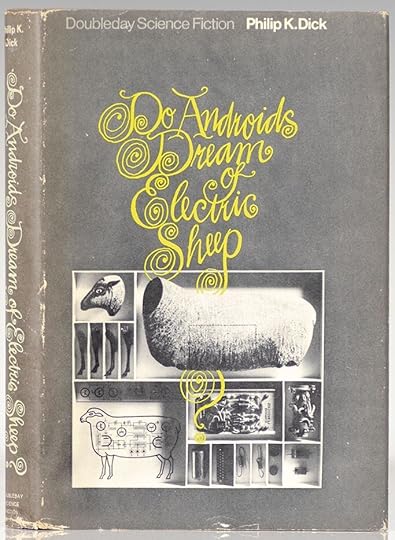

Philip K. Dick — Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dick started out writing for low-end SF digests and pulp mags, hustling to make rent. His stories were weird, paranoid, and obsessed with identity and reality—elements that would become hallmarks of his work. While he never found mainstream success in his lifetime, his posthumous fame exploded with film adaptations like Blade Runner and Minority Report.

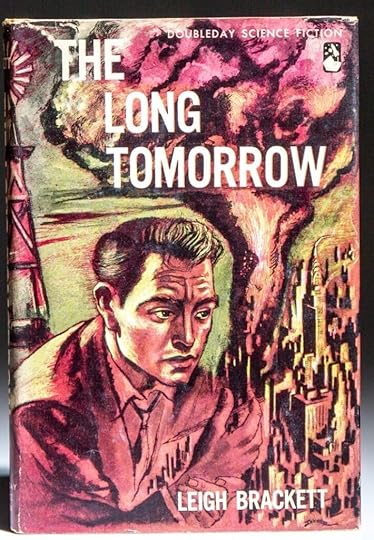

Leigh Brackett — The Long Tomorrow

Brackett was the queen of planetary romance, penning action-packed space operas for Planet Stories. She transitioned smoothly into screenwriting (The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, even a draft of The Empire Strikes Back), proving that pulp roots could lead to Hollywood heights.

___

These are just a few of the pulp-born authors who broke out and reshaped their genres—or invented new ones entirely. But the beauty of pulp fiction is that it was a wide-open field, and many more writers made their mark in ways both bold and subtle. Got a favorite author who started in the pulps and went on to greatness? Or a book that deserves more attention than it gets?

Is there a contemporary writer who is writing books that read like classic pulp? (That is, pure, can’t-sleep-yet entertainment?)

Drop your recommendations in the comments—I’m always up for discovering more pulp roots.

Latest releases:

Quiet Like Fire

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

May 14, 2025

AI at Worldcon: Friend or Foe?

So, Worldcon 2025 is making headlines, but not the kind you’d put on the back of a Hugo-winning novel. The organizing committee decided to use ChatGPT to help vet over 1,300 panelist submissions. They intended to streamline the flood of applications, maybe catch a few red flags, keep things moving.

Except it’s not going well.

The committee asked ChatGPT to pull up publicly available info on applicants, essentially using it like a souped-up search engine. But SFWA members have been running those same prompts on themselves, and the results? Pretty bonkers. We’re talking misattributions, missing publications, and some outright fabrications. Imagine finding out that ChatGPT thinks you wrote a series of cozy mysteries set in Atlantis when, in reality, you pen sci-fi space operas.

Now, some big-name authors are pulling out, including Yoon Ha Lee, and a few Hugo organizers have also stepped away in protest. Worldcon is scrambling to backtrack, issuing apologies and vowing not to use AI tools for this kind of thing in the future. But the damage may already be done.

And it’s not just Worldcon. AI is starting to creep into every corner of the literary world — from reviewing pitches to generating marketing copy to (yep) writing entire books. We’re all feeling the tremors of what that means for creators, publishers, and readers.

So, here’s what I’m curious about:

Would you attend a panel curated with AI assistance, knowing that some of the picks might be based on questionable info?Does it matter to you if AI is used to organize a con or vet participants, as long as the final say is still human?And the big one: If you knew a book was written with AI, would you read it?Sound off in the comments. I’m genuinely interested in what you think — because, like it or not, this whole AI-in-writing thing is just getting started.

Latest releases:

Quiet Like Fire

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

April 23, 2025

What Makes a Book a “Classic” in Science Fiction?

There are some books in science fiction that never seem to fade. Dune. Foundation. The Left Hand of Darkness. Decades later, we’re still reading them, studying them, arguing about them. They’ve carved out a permanent space on the shelf—and not just for their fans, but for the genre itself.

So what is it that makes a book a “classic”?

I’ve been thinking about this lately—not just the books we already call classics, but the ones we’re reading now that might wear that title in a few decades. What’s the secret formula for longevity in science fiction?

What Gives a Sci-Fi Book Staying Power?Here’s a short, very unscientific list of the ingredients that seem to help a book go the distance:

Big ideas. Classics tend to wrestle with fundamental questions—identity, humanity, power, time, survival. They’re not just about cool tech; they’re about why the tech matters.Voice. The writing may be sparse (Foundation), lush (Dune), or lyrical (The Left Hand of Darkness), but it has to feel distinct. A classic sounds like no one else.Re-readability. Great sci-fi doesn’t give you everything on the first read. It leaves doors open. You come back years later and find something new waiting.Timing. Some books become classics because they hit the zeitgeist just right—Neuromancer, for example—or helped shift the genre’s direction. It’s not just what they say, it’s when they said it.The Big Book Theory: Length, Immersion, and Emotional PunchThe late David Farland once wrote an essay about what he called “big fat books,” and I think he was onto something. He pointed out that many of the bestselling books of all time—Dune, Gone With the Wind, A Tale of Two Cities—were rejected again and again before someone finally took a chance on them. Why? Because they were “too long.” Too fat. Too much.

But readers don’t seem to mind. In fact, Farland argued that what makes a bestselling story isn’t just the story—it’s the experience. A truly immersive book does more than drop you into a different time or place. It takes you somewhere you want to go, and once you’re there, it gives you the emotional experiences you need to feel. You get to live something larger than life.

He also noted something else: most bestsellers in any genre tend to be long. Not just “300 pages and done” long—thousand page long. Because if the story grabs people, they want to stay.

So if we’re talking about what kinds of books end up as classics… maybe it’s no surprise that so many of them are hefty, immersive reads that aren’t afraid to go deep and wide, emotionally and narratively.

The Current Contenders: Future Classics in the Making?Speculating about future classics is a fun game—and highly subjective. But here are a few titles that, for me, have that staying power vibe:

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. JemisinThe worldbuilding is staggering. The themes—oppression, survival, rage, family—cut deep. And Jemisin’s voice is utterly her own. This trilogy has already won all the awards. I suspect it’s going to be required reading for generations to come.

Project Hail Mary by Andy WeirThis one is on a lot of people’s “future classic” lists. It’s got heart, science, optimism, and an unforgettable interspecies friendship. But full disclosure: it’s not a personal favorite of mine. I wrote about that here: Andy Weir’s Hail Mary – About Five Chapters Too Long.

That said, I do think it has classic potential—just probably not with my vote.

Dense? Absolutely. But it reads like a blueprint for the next century of Earth’s future. If it’s not already being studied in university classrooms, it will be.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky ChambersThis one might surprise people, but I think it has the legs to last. It’s small and quiet, but it hits big ideas—what do we do once our world is “fixed”? What does purpose look like in a post-collapse, post-scarcity society? It feels like the next wave of what sci-fi might become.

Children of Time by Adrian TchaikovskyEvolution, intelligence, and spiders. Lots and lots of spiders. It’s a sweeping, multi-generational epic that asks big questions about what it means to be sentient—and what it means to inherit a legacy, even if it isn’t your own.

The Genre’s Evolving—So Will the ClassicsWhat counts as “classic” sci-fi will shift over time. The canon is expanding. It has to. The stories that last will reflect that change—more voices, new structures, unfamiliar angles on the same old questions.

It’s not just about nostalgia or name recognition. The books that stick with us are the ones that make us rethink how we see the world… and maybe how we see ourselves.

What Do You Think?So, here’s my question to you: What science fiction book published in the last ten or twenty years do you think we’ll still be reading in fifty? What’s the sleeper hit you think deserves classic status?

Drop your picks in the comments. I’d love to see what stories you think are destined for the long haul.

Now available for pre-order:

Quiet Like Fire

Latest releases:

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

Galactic Reflections

April 16, 2025

Dystopia vs. Post-Apocalyptic: What Exactly Is The Hunger Games?

The line between dystopian and post-apocalyptic fiction has always felt a little blurry, hasn’t it? As someone who loves speculative fiction in all its forms, I often find myself asking: Is this book really dystopian, or is it post-apocalyptic wearing a shiny, Capitol-colored coat?

Case in point: The Hunger Games.

I recently picked up Suzanne Collins’ The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes—or tried to. I made it through the Hunger Games section of the story, only to discover (surprise!) there was an entire Part II waiting for me after the climax I thought I was reading toward. Reader fatigue set in hard. And while I could write a whole post about the ever-expanding page counts of modern bestsellers, let’s park that soapbox for now.

Back to genre. What is the genre of The Hunger Games, exactly?

It’s tempting to say “dystopian,” and most people do. After all, Panem is a tightly controlled society where a tyrannical government uses fear, spectacle, and scarcity to keep its citizens compliant. The Capitol is garishly privileged. The Districts are brutally oppressed. Surveillance is constant. Rebellion is deadly. That all screams dystopia.

But then there’s the backstory: a world destroyed by climate disaster, war, and collapse. Panem rose from the ashes of what used to be North America—so we’re clearly in post-apocalyptic territory. Technically, this is a future shaped by a catastrophic end. That counts, right?

So, which is it?

The Spectrum TheoryMaybe we’re thinking about this wrong. Maybe “dystopia” and “post-apocalyptic” aren’t boxes so much as points on a spectrum.

Post-apocalyptic fiction tends to focus on the aftermath—survival, rebuilding, scavenging, and loss. The emphasis is on what was destroyed, and how people try (and often fail) to recover from that destruction. Think The Road, or Station Eleven, or Mad Max. The systems are gone, or barely holding on.

Dystopian fiction, on the other hand, focuses on what came next—how a new system emerged from the ashes, and how it shapes (and warps) the lives of the people trapped inside it. Dystopias are less about the fall, more about the control.

By that logic, The Hunger Games sits at an interesting midpoint. Panem exists after the world ended, but its story isn’t about the fall—it’s about the aftermath of the rebuilding. The Capitol is what rose in place of democracy. The Games are what replaced civil discourse. It’s a dystopia born of apocalypse.

But if you pause and peer beneath the surface—if you think about what Collins doesn’t put on the page—you can feel the cold breath of the apocalypse in every corner of Panem. The empty spaces between Districts. The forgotten technology. The tacit understanding that the rest of the world might not exist anymore. That the scars of the war that ended everything still throb beneath the Capitol’s glitter and propaganda.

It’s both. Dystopian at the forefront. Post-apocalyptic in the bones.

When Does It Shift?If we’re looking at that sliding scale, I’d argue that the shift from post-apocalyptic to dystopian happens when a new structure—usually some form of government or ideology—becomes more oppressive than the apocalypse was destructive. When people stop struggling to survive in a broken world, and instead start struggling to live within a system that demands submission. That’s when the dystopia begins.

In Panem, people have survived. There are trains. There’s infrastructure. There’s horrifying entertainment. Life goes on—but it’s brutally controlled. That’s the dystopian element taking center stage.

Final ThoughtSo what’s the point of teasing all this apart? Well, genres are more than marketing labels—they shape how we experience a story. They tell us what to expect, and what to look for. Recognizing that a world can be both broken and controlled—post-apocalyptic and dystopian—gives us a richer reading. It shows us not just how the world ended, but how humanity went on—and sometimes, how we made things even worse.

And as for The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes? Maybe I’ll finish it someday. Or maybe I’ll just go read a tightly plotted 300-page sci-fi novel that ends where it’s supposed to. We all have our limits.

Now available for pre-order:

Quiet Like Fire

Latest releases:

Solar Whisper

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

Galactic Reflections

April 2, 2025

The Science of Generation Ships: Could We Actually Do It?

Under one of my other pen names, I’ve written an entire series set aboard a generation ship on a thousand-year voyage to the Coalsack area of space. So I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what it would take to actually pull something like that off.

Short answer? It’s not looking good. Not yet.

The idea of generation ships has been a science fiction staple for decades. It’s irresistible: a giant spacecraft full of people who are born, live, and die aboard a ship that never lands—where their descendants (hopefully) reach a far-off destination centuries later.

But how close are we, really, to building one?

We’re Still Dreaming BigBack in the day, stories like Brian Aldiss’s Non-Stop (1958) showed us how things could go completely sideways. The crew forgets they’re on a ship at all, society degrades into something tribal, and rediscovery of their situation is the whole story arc.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Aurora (2015) hits us with some cold reality. Ecological collapse, microbiome instability, psychological strain—it paints a very believable picture of how generation ships might fall apart before they get anywhere. Not exactly a glowing recommendation.

Other recent takes—like An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon and Braking Day by Adam Oyebanji—lean into the social and cultural messiness that would inevitably evolve in a ship-bound society. Humans don’t stop being human just because you seal them inside a tin can and point them at the stars.

And they’re not wrong.

So… Could We Do It?Let’s break it down.

1. We Need Gravity. Badly.This is the big one. We have decades of data now from astronauts, and the news isn’t great. Long-term exposure to microgravity messes with basically every system in the human body—muscles waste away, bones lose density, and your cardiovascular system gets lazy.

And then there are the weird little details you never think about until you read astronaut diaries: the tops of your feet grow calluses from hooking under foot straps all the time, and the soles of your feet go baby-soft. It’s disorienting, physically and mentally.

So, if we’re going to send generations of people into deep space, we need artificial gravity. The current best idea is to spin part of the ship to create centrifugal force—but that brings a whole mess of engineering challenges, especially on a structure big enough to house multiple generations of people, ecosystems, and infrastructure.

Still doable. But hard.

2. Closed Ecosystems Are Tricky BeastsA generation ship can’t rely on supply runs. Everything—air, water, food, waste—has to be endlessly recycled. We’re starting to get a handle on this (the ISS uses some of this tech already), but scaling it up to support hundreds or thousands of people for centuries? That’s a big ask.

We’d essentially need a fully functioning biosphere in a can. With backups. And backup-backups. And people trained to maintain it for their entire lives, and then train their kids to do the same.

No pressure.

3. Humans Are… ComplicatedEven if we solve the engineering problems, we’re still left with the social ones. How do you maintain a healthy, stable society when no one on the ship will ever see Earth—or their destination?

Cultural drift is real. Factions will form. Beliefs will evolve. People will want to rewrite the rules. And if things go sideways, there’s no help coming.

Robinson’s Aurora really leans into this—how stress fractures in a closed society, over centuries, become unavoidable. You can’t pause and reset. It just keeps going… or it doesn’t.

The Fiction vs. the ScienceI love generation ship stories for the same reason I love writing them: they force us to think long-term. Really long-term. Not just how to survive, but how to keep civilization going in the face of isolation, entropy, and human nature itself.

In fiction, you get to imagine a crew that pulls it off. Or, sometimes, one that crashes and burns in spectacular fashion. Either way, it makes for a great story.

In real life? We’re still at the theory-and-whiteboards stage.

Will We Ever Do It?Maybe. But it’ll take a massive leap—not just technologically, but culturally. We’d have to be okay with sending people into the void knowing they’ll never see the end of the journey. That’s a tough sell, no matter how inspiring the mission.

Until then, generation ships are our mirror: a way to explore who we are when everything familiar is stripped away, and all we have left is ourselves, a metal hull, and the stars ahead.

What about you? Got a favourite generation ship story that blew your mind (or broke your heart)? I’d love to hear about it. Drop the title—and the author if you remember—in the comments. I’m always on the lookout for more takes on life between the stars.

Now available for pre-order:

Solar Whisper

Latest releases:

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

Galactic Reflections

The Return of the Peacemaker

March 26, 2025

The 2024 Nebula Award Finalists Are Here — Let’s Talk About Them

Every year when the Nebula finalists are announced, I get a little zing of anticipation. If you’re a fan of science fiction and fantasy, you probably know the feeling—wondering what made the cut this time, what surprises the list holds, and what favorites didn’t quite make it. The 2024 shortlist just dropped, and there’s a lot to dig into.

The Nebulas are a big deal in the SFF world. Think of them as the genre’s version of the Oscars—except it’s writers voting for writers. The other major award is, of course, the Hugos. Interestingly a lot of titles win both awards, so the phrase “Nebula and Hugo Award Winner” appears on many covers. The Hugos are reader-voted awards, the flipside of the Nebulas.

That peer recognition is one of the things that makes the Nebulas special. They’ve spotlighted some mind-bending, genre-shaping works over the years. We’re talking Dune, The Left Hand of Darkness, Neuromancer, Parable of the Sower… books that didn’t just tell a great story—they shifted what the genre could be.

This year’s Best Novel finalists are:

Sleeping Worlds Have No Memory by Yaroslav BarsukovRakesfall by Vajra ChandrasekeraAsunder by Kerstin HallA Sorceress Comes to Call by T. KingfisherThe Book of Love by Kelly LinkSomeone You Can Build a Nest In by John WiswellYou can see the finalists in all categories here. Many of the shorter titles have links to online pages where you can read the story for free.

Which of these have you read? Any favorites? If you could vote, which one would you hand the Nebula to? And maybe most interesting of all—what book do you think should’ve been on this list but isn’t? Eligible book are any titles released in 2024.

Why the Nebulas Matter (And Why I Care)

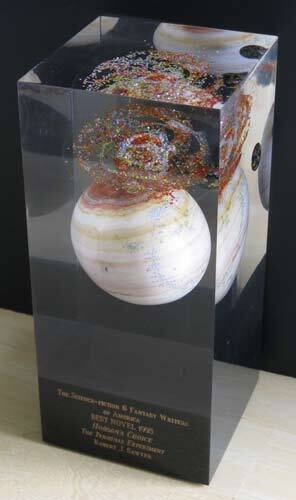

The Nebulas have been around since 1965, started by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA). SFWA is basically the professional guild for SFF writers—supporting careers, advocating for authors’ rights, and helping writers navigate the business side of publishing. I’m proud to be a full member, which means I’ve met their criteria for professional publication (yep, I’ve got the battle scars to prove it!).

Some of the greats have been members over the years—people like Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Isaac Asimov, and Anne McCaffrey. These are the writers who shaped the genre—and, let’s be honest, shaped a lot of us too.

One cool thing SFWA does is publish Nebula Award anthologies each year—collections of nominated short fiction and other standout pieces. If you’re looking for a taste of the best speculative fiction being written right now, those anthologies are a great place to start (although they’ve got a bit behind, there are plans to catch up).

When Are the Winners Announced?

Winners will be revealed during the Nebula Conference in May 2025. It’s a whole weekend of panels, workshops, networking, and general celebration of SFF. And while most of us aren’t in it for the awards, let’s face it—getting nominated (or winning) a Nebula is a milestone moment.

So, let me know—have you read any of the 2024 finalists? Which ones lit a fire in your imagination? And what amazing books do you think were snubbed?

Let’s talk books.

Now available for pre-order:

Solar Whisper

Latest releases:

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

Galactic Reflections

The Return of the Peacemaker

March 19, 2025

Why I Write Under a Pen Name

I’m pretty open these days about the fact that Cameron Cooper is a pen name. But that wasn’t always the case.

When I first started publishing as Cameron, it was a complete secret. And while I “came out” just over a year ago, I don’t think I’ve ever really explained to readers why I chose to use a pen name in the first place—or why I still do.

Why I Started Using a Pen NameIronically, I didn’t start my science fiction career with a pen name at all. When I first branched into space opera, I published under my real name, Tracy Cooper-Posey.

A Big Name author once told me that indie writers could “write anything they want.” That sounded fantastic—after all, the indie revolution was all about freedom, right? So, I went all in. I released The Indigo Reports under Tracy Cooper-Posey and even participated in Kevin J. Anderson’s curated space opera story bundle.

In fact, if you dig into the bowels of Amazon, you can still find print editions of the first two books of The Indigo Reports series with my real name on them. Amazon won’t take them down.

But when I first published them, everything seemed to be going well.

Except, I’d made a critical mistake.

Amazon’s algorithms had already pegged Tracy Cooper-Posey as a romance author. So when I published space opera under the same name, Amazon showed those books to my romance fans. And they didn’t buy them. In droves.

Amazon’s response? “Oh, okay. If Tracy’s audience doesn’t like these books, they must be duds.” So it stopped showing my science fiction to anyone.

Then, things got worse.

Amazon started showing my romance books to science fiction readers. They ran screaming, too.

At this point, the algorithm threw up its hands and effectively shadow-banned everything under my name. And because I was in Kindle Unlimited at the time, which demands exclusivity (that is, my books were ONLY for sale on Amazon), and where organic visibility is crucial, this was a disaster.

The moment I figured out what was happening, I knew I had to make a change. I republished The Indigo Reports under a brand-new name: Cameron Cooper. Then I finished the series. And then I wrote more. And more. And suddenly, I had an entire space opera career under a brand-new name.

Why Cameron?Cameron Cooper was my brother. He passed away many years ago.

Before my father died, I asked if I could use Cameron’s name as a pen name. He agreed. And so, Cameron Cooper was born.

At the time, I kept things deliberately vague about Cameron’s gender. Occasionally, I’d hint that Cameron might be a guy, but I never outright stated it. The irony? Both Tracy and Cameron are gender-neutral names. My parents had planned for me to be Tracy whether I was a boy or a girl. And my brother was going to be Cameron no matter what.

Now, every time I release a Cameron Cooper book, I send my mother a print copy. She has an entire shelf full of books by Cameron Cooper. That alone makes it all worthwhile.

Why I “Came Out”Not long after launching Cameron Cooper, I left Kindle Unlimited. The damage Amazon’s algorithms had done was beyond repair, and I was making no money. So, I went wide.

The space opera books kept selling. Readers kept asking for more. So I kept writing.

Then, a series of unfortunate events forced my hand.

SFWA outed me. In a very public blog post, they used my real name. I had them fix the post…but it was too late. Amazing Stories had already picked up the news and posted it on their site. The TBR Conference invited me to speak on a panel. I was a finalist for SPSFBO #2, and attending the panel would mean appearing in public as Cameron Cooper. But too many people already knew what I looked like as Tracy—after all, I’ve done multiple live events, podcasts, video interviews, and I have my own YouTube channel.The panel organizers couldn’t guarantee the moderator would remember to call me Cameron. Or that they’d use the name consistently.I thought about it for a while. At this point, I was fully wide, so I wasn’t relying on Amazon’s algorithms anymore. (Side note: Amazon—and all the other retailers—still use algorithms. The other retailers are just not as aggressive as Amazon.)

Since I was no longer beholden to KU’s ranking system, I realized there was no reason to keep the secret. So I made a quiet decision.

I didn’t make a big announcement. I just updated my biographies across my platforms. Then, I sat on that TBR Conference panel and introduced myself as Tracy-writing-as-Cameron. And I kept writing.

Why I’m Still Using a Pen NameEven though I’ve made the connection between Tracy Cooper-Posey and Cameron Cooper public, I still keep them separate. Why?

Branding. Readers know what to expect. Someone picking up a Cameron Cooper book won’t be blindsided by a super-steamy paranormal romance. And romance readers won’t accidentally end up in a dense space opera series when they were expecting a cozy vampire love story.Retailer sanity. Even though I don’t stress over Amazon’s algorithms anymore, it’s still smart business to help them sell my books effectively. Keeping my pen names separate makes that easier.My mum loves getting Cameron’s books. And as long as she keeps putting them on her shelf, I’ll keep writing them.So that’s the story. That’s why I created Cameron Cooper, why I eventually “came out,” and why I still publish under a pen name.

And honestly? It was one of the best decisions I ever made.

Now available for pre-order:

Solar Whisper

Latest releases:

Ptolemy Lane Tales Omnibus

Galactic Reflections

The Return of the Peacemaker