Ezra Klein's Blog, page 898

February 14, 2011

Is the administration being too optimistic, cont'd

I mentioned earlier that the budget includes more optimistic economic predictions than what the Congressional Budget Office is using. This in turn makes the projected budget deficit smaller. In a briefing today, Austen Goolsbee explained where his numbers were coming from, and notes that the administration's projections are more pessimistic than the consensus projections of private-sector forecasters:

Four short points: The first is that the forecast that we use has to be locked in for planning purposes as of mid-November of last year, so it predates the tax deal. As you know, many of the private forecasters upped their forecast based on what was in the tax deal, and most of that is not in the forecast.

Number two, real GDP growth on a year-over-year basis, the administration is forecasting 2.7 percent in 2011, 3.6 percent in 2012, 4.4 percent in 2013. So our growth rate for 2011 is a fair bit lower than the consensus of private forecasters surveyed by the blue chip or by the Survey of Professional Forecasters.

The longer run we anticipate catching back up, that the potential GDP of the United States has not been severely damaged by this recession. So our medium-run forecast is a bit faster. It's within the so-called central tendency that comes out of the Fed FOMC forecast of last November, which is a -- the reasonable range in which they drop off the highest and lowest. It is rather in the center of that central tendency.

So over a five-year period -- the typical recession since World War II has been followed by a growth rate of a little less than 4.2 percent over five years. Our forecast is about 3.8 percent over five years. So it's slower than the typical recovery and we assume that because it's harder to get out of a financial recession.

The third point I'd raise is that the unemployment rate in our projection is that at the end of 2011 it would be 9.1 percent; by the fourth quarter of 2012, it would be 8.2 percent. That was obviously made in mid-November. The unemployment rate currently stands at 9.0 percent. Unemployment is likely to fluctuate through the year, but any revisions that we have will come out at the mid-session review.

Finally, for inflation we're projecting that in 2011 the CPI inflation will be 1.3 percent -- so actually decline from where it is now. It's very much in line with other professional forecasters, and that in 2012, 2013 and beyond we'd go back to something like the Fed's and others' 2 percent inflation level.

As I said in the original post, this one is too technical for me to judge.

Two budget dodges to watch for

Listening to the rhetoric surrounding the various budgets of Republicans and Democrats, a few things stand out: Republicans keep conflating cutting spending with cutting deficits. And it sounds to me like Democrats are banking on the fact that the public is a bit fuzzy on the difference between cutting the deficit and cutting the debt.

Take John Boehner. "We're broke," he said on Sunday's Meet the Press. "When are we going to get serious about cutting spending?" To be "not broke," however, you need the amount of money you're making to match the amount of money you're spending. Republicans want to cut spending, but they want to cut revenues even more: Just today, Mike Pence and Jim DeMint introduced the "Tax Relief Certainty Act," which would make the Bush tax cuts permanent. That would cost trillions of dollars, and they offer no offsets. It'd all just go on the national credit card. If you cut spending by $2 trillion and cut revenues by $4 trillion, not only are you still broke, but you're actually more broken than you where when you started.

Democrats, meanwhile, are talking about cutting annual deficits, but they're not talking about cutting total debt. That distinction occasionally gets lost, I think. When Sherrod Brown says, "the President's budget proposal will put us on track to cut the deficit in half in his first term," it sounds like he's talking about the debt we've accumulated, not merely the borrowing we're going to do that year. But getting deficits down to three percentage points of GDP in 2017 doesn't mean that's all we've borrowed, or are paying off. It means that's all we're borrowing in 2017. This isn't necessarily a case of intended misdirection -- the language here is a bit imprecise -- but there's a reason you're hearing a lot of deficit numbers and very few debt numbers from the administration.

Featured Advertiser

White House calls for Social Security talks

This hasn't gotten a ton of attention, but the budget includes a pretty explicit call for Congress and the administration to commence talks on Social Security reform. The administration even lays out its starting position:

The President believes that we should come together now, in bipartisan fashion, to strengthen Social Security for the future. He calls on the Congress to follow the example of great party leaders in the past — such as Speaker Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr. and President Ronald Reagan — and work in a bipartisan fashion to strengthen Social Security for years to come. Guiding the Administration in these talks will be the President's six principles for reform:

• Any reform should strengthen Social Security for future generations and restore long-term solvency.

• The Administration will oppose any measures that privatize or weaken the Social Security system.

• While all measures to strengthen solvency should be on the table, the Administration will not accept an approach that slashes benefits for future generations.

• No current beneficiaries should see their basic benefits reduced.

• Reform should strengthen retirement security for the most vulnerable, including low-income seniors.

• Reform should maintain robust disability and survivors' benefits.

For an idea of the kind of reform they're talking about, check out the proposal Christian Weller produced for the Center for American Progress.

The stimulus was small

At least when compared to the competition:

This paper studies the patterns of fiscal stimuli in the OECD countries propagated by the global crisis. Overall, we find that the USA net fiscal stimulus was modest relative to peers, despite it being the epicenter of the crisis, and having access to relatively cheap funding of its twin deficits. The USA is ranked at the bottom third in terms of the rate of expansion of the consolidated government consumption and investment of the 28 countries in sample.

On the same point, Paul Krugman posts this graph looking at total public spending -- that is to say, federal spending, which went up, but also state and local spending, which went down -- in recent years:

"Looking at this graph," Krugman asks, "if you didn't know there had been a 'massive' stimulus, would you even have suspected that there had been any stimulus at all?"

Why cover the budget at all? (Plus: E2I2!)

A couple of readers have e-mailed to ask why I'm wasting all this time on a budget document that'll never survive negotiations with a Republican Congress. The answer, put simply, is that it's important to know what the White House wants, and where they're starting from in negotiations. If the cuts to the military had been much larger, you could've imagined military cuts being a big part of the eventual deal between Republicans and Democrats. Now they won't be. If the White House had opened up entitlements, or tax expenditures, that would've made them likelier elements in an eventual compromise.

The budget also previews the White House's political strategy going into these negotiations -- and the public relations campaign that will precede them. And E.J. Dionne gets their message just right:

Today begins the war over E2I2.

The great budget battle of Bill Clinton's presidency was waged around a set of initials also inspired by the "Star Wars" character R2D2. Clinton's lieutenants jauntily encapsulated his fight against Republican cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, education and the environment as a defense of M2E2.

For President Obama, the battle lines will be drawn on investments in -- or, as Republicans would say, spending on -- education, energy, infrastructure and innovation, thus E2I2.

2012 Budget: Agency-by-agency

My colleagues at the Washington Post have a great round-up of what the budget means for various federal agencies. It's worth heading over and clicking around.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget blasts the White House

"It is encouraging that the Administration identifies some areas for real savings. However, the total level of savings is far short of what is needed and too many heroic assumptions are used to achieve them," said Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. "This budget fails to meet the Administration's own fiscal target, it fails to tackle the largest problems areas of the budget, and it fails to bring the debt down to an acceptable level."

"While we can certainly appreciate the difficult political environment in which the budget is introduced, the glaring omission of any significant entitlement reforms and the excessive use of 'fill-in-the-blank' budgeting does not help to advance the conversation," said MacGuineas.

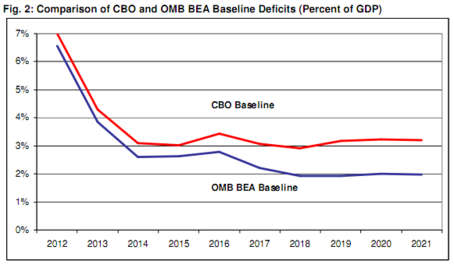

The interesting argument that CRFB makes -- and that I've been hearing from other budget wonks, too -- is that the underlying economic assumptions in the budget are substantially more optimistic than what the Congressional Budget Office is using, and that's part of how the administration gets deficits so low. "Under CBO's 'current law' projections (those which allow for the expiration of the 2001/2003/2010 tax cuts and other measures) the deficit reaches 3.2 percent of GDP by the end of the decade and the debt reaches 77 percent. Under OMB's current law projections, the deficit reaches 2 percent and the debt 70 percent. This alone has us concerned that CBO's estimate of the President's budget won't be nearly as charitable as OMB's – and reality might not be either." Here's the graph:

I'm not a macroeconomic forecaster, so I'll leave it to others to adjudicate this debate. But whose economic assumptions turn out to be right really matters.

Update: Here's the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities' take. They say the budget "does not go nearly far enough to keep the debt stabilized in later decades" but that criticism "ignores the fact that had the budget included a large array of specific proposals for longer-term deficit reduction — ranging from increased taxes to changes in Social Security — that likely would have made it harder, not easier, for the Administration and Congress to eventually reach bipartisan agreement on those matters."

The Defense Department won the future, or at least the budget

One of the big lessons of this budget is that if you work in the federal government, you want Defense Secretary Robert Gates on your side when the budget cuts come around.

The military made out quite nicely in the 2012 budget proposal. The administration is cutting $78 billion from the Defense Department's budget -- known as "security discretionary spending" -- over the next 10 years. That's a bit of a blow, but compare it to the $400 billion they're cutting from domestic discretionary spending -- that's education, income security, food safety, environmental protection, etc. -- over the next 10 years. And keep in mind that the domestic discretionary budget is only half as large as the military's budget. So if there were equal cuts, the military would be losing $800 billion. And you could argue that the politics of that make some sense: Military spending is one of the least popular categories of federal spending.

That's what the Fiscal Commission had wanted to do. "One of the Commission's guiding principles is that everything must be on the table" they wrote. For that reason, they recommended "equal percentage cuts from both sides."

Nor were they the only ones who thought such cuts possible. The Sustainable Defense Task Force, formed by Barney Frank and Ron Paul (among others) and staffed by a who's who of military policy experts from both sides of the aisle, produced a report (pdf) recommending up to $960 billion in cuts over the next 10 years. These were cuts, the experts said, "that would not compromise the essential security of the United States." Others disagree with that judgment, of course. One of them was Gates, who warned that major cuts in his department would be "catastrophic."

He won. The $78 billion in cuts are the exact $78 billion in cuts Gates recommended. I bet there are more than a few Cabinet secretaries who wish they had that kind of power over the president's recommendations.

It's interesting to think about this in terms of the president's focus on "winning the future." He's been very careful to speak of our challenge as primarily one of bettering ourselves and our country, not fighting our competitors. To win the future, we need to educate our people, rebuild our roads, expand broadband Internet, invest in research and development. And some of those categories are, to be sure, getting a boost in this budget. But only a small one. The R&D budget, for instance, goes up by one percentage point. And many important programs -- like Pell Grants -- are getting shaved down.

If this is a fiscally responsible budget, then cutting $500 billion -- forget $800 billion -- from the Defense Department would've opened room for much more domestic investment. It also could've gone to pay down the debt. As it is, we're pumping that money into sustaining a fighting force that's orders of magnitude larger than anything retained by any other country. The theory implicit in that decision suggests that the fight to win the future might be rather different than the Obama administration is letting on.

Photo credit: White House

Lunch Break

Ezra Klein's Blog

- Ezra Klein's profile

- 1105 followers

-thumb-454x357-34710.png)