Ezra Klein's Blog, page 900

February 11, 2011

Who's buying more stuff from us in one graph

The Commerce Department says export growth was 14.9 percent in 2010. That's pretty good, though it's pretty good in large part because 2009 was pretty bad. Here's who got our goods:

One way to read this graph is that we're in a lot better shape today because China is in a lot better shape than it was in 10 years. One of our "win the future" benchmarks is doubling exports in the next five years. That's pretty much impossible if China doesn't also keep winning the future and buying more stuff from us.

What's an elite education worth?

At the beginning? Quite a bit. Over time? Not as much.

In this paper we compare the labor market performance of Israeli students who graduated from one of the leading universities, Hebrew University (HU), with those who graduated from a professional undergraduate college, College of Management Academic Studies (COMAS). Our results support a model in which employers have good information about the quality of HU graduates and pay them according to their ability, but in which the market has relatively little information about COMAS graduates.

Hence, high-skill COMAS graduates are initially treated as if they were the average COMAS graduate, who is weaker [than an] HU graduate, consequently earning less than [HU] graduates. However, over time the market differentiates among them so that after several years of experience, COMAS and HU graduates with similar entry scores have similar earnings. Our results are therefore consistent with the view that employers use education information to screen workers but that the market acquires information fairly rapidly.

How the administration will get rid of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

I mentioned earlier that the administration plans to get rid of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. But I didn't say much about how they mean to go about doing it. Luckily, Daniel Indiviglio has a nice, clean summary:

One change would be to gradually increase the guarantee fees that [Fannie and Freddie] charge, so that private guarantors would be able to better compete. Another change would be to require Fannie and Freddie to obtain more private capital to cover subsequent credit losses. The Treasury also intends to reduce the size of mortgages that qualify for Fannie and Freddie guarantees. Finally, the administration intends to wind down Fannie's and Freddie's mortgage portfolios, by at least 10% per year.

I guess this was predictable

The Cato Institute invites you to a Policy Forum:

Is Dodd-Frank Constitutional?

featuring

Mark Calabria

Director of Financial Regulatory Studies, Cato Institute

Hon. C. Boyden Gray

Former White House Counsel

Timothy R. McTaggart

Partner, Pepper Hamilton LLP, and former Delaware State Bank Commissioner

moderated by

Ilya Shapiro

Senior Fellow in Constitutional Studies, Cato Institute

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 was intended to "promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end 'too big to fail,' to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes." The law is extraordinarily complex, requiring almost a dozen federal agencies to complete anywhere between 240 to 540 new sets of rules, plus about 145 studies that will affect rulemaking. There has been much debate over whether the law will accomplish its stated intent, but there are also growing concerns about its constitutionality, primarily due to separation of powers, vagueness, and due process issues. Central to that discussion is the fact that Dodd-Frank grants administrative agencies — including the newly created Financial Stability Oversight Council and Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection — broad and unchallengeable discretionary authority. Does Dodd-Frank provide effective oversight by any branch of government — Congress, the president, or the judiciary? How can constitutional concerns about the law's grants of regulatory power be resolved? Please join us for a discussion of these important issues.

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

Noon

You can sign up to attend here.

Should we pay members of Congress for performance? Can we?

Can we pay members of Congress for being productive?

That's what Rep. Jim Cooper (D-Tenn.) wants to do. "The real trouble with Congress is that you get what you pay for, and we are paying for the wrong things," he said in a recent speech at Harvard's Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. "Right now taxpayers are paying for mediocre members of Congress to look good while ducking fundamental issues in order to get reelected. Fixed salaries do much more to perpetuate the terrible status quo than most people realize."

The problem is, how do you measure congressional productivity? Bills passed? Constituents helped? Television hits? Even Cooper doesn't know.

Initially, I wrote his idea off as economic thinking run amok. But an interview today changed my mind, at least a bit. Cooper may not know how to pay congressmen to be more productive -- and he's not for higher pay overall. But he makes a good case that they are currently paid -- or at least rewarded -- for the wrong sorts of productivity.

"If you look at it carefully," he says, "we're already being paid for performance. But it's by special interests. And even here on the Hill, we kind of pay ourselves for a certain type of performance. Party leadership hands out all these perks: Committee assignments, staff privileges, annex offices, pages, even permission to travel. And then there are campaign contributions from the DCCC."

So what to do about it? That's a bit harder. There are crude measures of productivity like attendance at votes, hearings, and issue meetings. But it's not clear where exactly that gets you. It's important for a member of Congress to show up for a vote, but is it really better performance for her to help name a post office in another state than to meet with a constituent or read an issue brief? Another option is to reduce the bad types of performance pay, or at least their appeal, through things like campaign finance reform. But perhaps you folks have some subtler, better ideas for how to do this. Can we pay members of Congress for performance?

Lunch Break

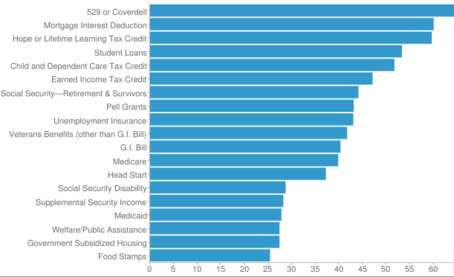

The submerged state in one graph

"The submerged state" is Cornell professor Suzanne Mettler's term for the slew of government policies that most Americans don't know exist or don't realize are government policies. As part of her paper -- gated, sadly -- exploring how these invisible programs affect the politics of social policy, she designed a study asking people first whether they'd ever used a government program and then later whether they had ever taken advantage of 19 specific programs. The overlap between people who didn't think they used government programs and people who admitted using government programs is shockingly large:

Of course, it's not as if these folks really don't know they're taking advantage of these programs. Try eliminating the mortgage interest deduction, or the tax break for employer-sponsored coverage, and you'll find that out real fast. But Americans tend to distinguish between benefits they feel they've earned -- Social Security, say -- and benefits they consider giveaways. It's not a very useful distinction, but it's a convenient, and thus a powerful, one. We have a vast welfare state for the middle and upper classes, but the politics of it are entirely different.

For instance: Among the more mind-blowing facts about the health-care system is that the tax break we give to employer-provided insurance dwarfs the cost of the entire Affordable Care Act -- and, if you want to take the concept a bit further, this means those of us who don't get insurance from our employers are being forced, even mandated, to pay for those of us who are. But this break is largely uncontroversial in American politics, while subsidies to help people who can't afford health insurance are extremely controversial.

Featured Advertiser

In praise of 'Planet Money'

I've become a recent convert to podcasts. Particularly after I found that the iPhone/iPod software allows you to listen to them at double speed. And so, in recent weeks, I've caught up with NPR's "Planet Money" show. And I want to take a second to gush about the work it's doing.

There are two recent episodes I particularly want to recommend. The first is "Writing the Rules." You know how wonks keep saying that the rulemaking process for bills such as the Affordable Care Act and Dodd-Frank are really the crucial process going forward? "Planet Money" actually goes inside that process. They put a microphone in the room while three regulators at the FDIC take out their dog-eared copies of the law and commence trying to figure out what it's telling them -- and everyone else -- to do. They head over to one of the public hearings that's supposed to give ordinary Americans a chance to weigh in on the new rules but is really just a forum for lobbyists to press their case. As someone who occasionally attempts to report on the rulemaking process, I know it's hard to do good journalism on it. It's almost impossible to do fun journalism on it. "Planet Money" managed both.

The second is "The Moral of the Financial Crisis." This episode is from the week the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission released its final report. That report, as you may remember, ended up bitterly partisan: Every Republican dissented. "Planet Money" spoke to a number of the commissioners and did a better job than anyone else distilling why: Part of it was personal -- the Republicans felt the Democrats treated them poorly, and the Democrats thought the Republicans were trying to impede the commission's work. But part of it was substantive: Although the two sides agreed on almost everything about the crisis, the Democrats considered it foreseeable and preventable and the Republicans didn't. That matters because, to the Republicans, concluding the crisis could've been stopped ratifies the idea that we need new regulations and more regulators. If it's more of a freak event that no one could have prevented, the case for more regulations is weaker, as they wouldn't have stopped it anyway.

Both episodes are well worth your time, as is subscribing to the show's podcast and blog. They're both free, after all. And props to "Planet Money" for making topics that a lot of other people have given up on clear and accessible, and even fun.

Mubarak steps down

I have zero insight to offer on the remarkable events in Egypt. But I did find this essay to be helpful in trying to think through what's happening there, and who's playing what role. An excerpt:

Many international media commentators – and some academic and political analysts – are having a hard time understanding the complexity of forces driving and responding to these momentous events. This confusion is driven by the binary "good guys versus bad guys" lenses most use to view this uprising. Such perspectives obscure more than they illuminate. There are three prominent binary models out there and each one carries its own baggage: (1) People versus Dictatorship: This perspective leads to liberal naïveté and confusion about the active role of military and elites in this uprising. (2) Seculars versus Islamists: This model leads to a 1980s-style call for "stability" and Islamophobic fears about the containment of the supposedly extremist "Arab street." Or, (3) Old Guard versus Frustrated Youth: This lens imposes a 1960s-style romance on the protests but cannot begin to explain the structural and institutional dynamics driving the uprising, nor account for the key roles played by many 70-year-old Nasser-era figures.

To map out a more comprehensive view, it may be helpful to identify the moving parts within the military and police institutions of the security state and how clashes within and between these coercive institutions relate to shifting class hierarchies and capital formations.

As they say, read the whole thing.

Ezra Klein's Blog

- Ezra Klein's profile

- 1105 followers