Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 29

May 28, 2015

Hitting them in their wallet

The news today is full of the latest hacking caper, which has breached the US Internal Revenue Service and stolen the tax return information of more than 100,000 US citizens. And the best part: It has been determined that the culprits are Russians, which means that even if they could be identified, they are beyond our government’s ability to exact any punishment or retribution. Next year, thousands of people are likely to try to submit tax refund requests, only to find out their refunds have already been sent to a fake overseas account, never to be seen again.

The news today is full of the latest hacking caper, which has breached the US Internal Revenue Service and stolen the tax return information of more than 100,000 US citizens. And the best part: It has been determined that the culprits are Russians, which means that even if they could be identified, they are beyond our government’s ability to exact any punishment or retribution. Next year, thousands of people are likely to try to submit tax refund requests, only to find out their refunds have already been sent to a fake overseas account, never to be seen again.

The US is increasingly coming under cyber attack from foreign nationals, stealing our money and credit, and remaining outside of US law. It’s a clear indication of our lax and outdated security systems, and how vulnerable we are to cyber theft.

Americans are notoriously slack when it comes to some things… but they usually play a different tune when you hit ’em in their wallets. Which is why we might see some changes to security, and we may see them soon.

Americans also have a habit of accepting things that may not be the best idea, if it gives them convenience—or, more to the point in this case, if it takes away a serious inconvenience. And the idea of losing money, as well as the prospect of having to tighten security measures to protect that money, will likely be enough to force us to change the way we handle security, online and in person.

If you use online banking or other financial sites, you may have noticed how some of them are trying to beef up security with multiple secret questions, the presence of familiar images, and much more robust passwords that must be manually entered. The thing about these new systems is, they can often be beat by just a little light research, or things like keystroke recorders (which can work through walls, people) or a nice, simple hidden camera. And computers have gotten powerful enough to burn through the most obscure one-word passwords in minutes… even seconds.

So where does this take us? To the one form of secure identification that cannot be beat by simple keystrokes or cameras: Biometrics. (God, I hope you knew I was going here.)

Scanning the veins and blood flow in your hand is the future of biometric security.

Biometric identification has gotten much more sophisticated and robust than the old fingerprint reader you might have seen on some computers or in the current spy thrillers. The latest reading systems can not only identify body biometrics like fingerprints or retinas with much greater accuracy… but they can scan into the body, pulling a live 3-D image of the veins in your hand or eye, defeating simple photo mimicry. They can even detect the subtle motion of blood through those veins, certifying that the identifying print isn’t coming from a limb severed by a criminal to access your accounts.

These biometric systems can provide a much stronger level of protection to our accounts, our credit, our information, and our money. And they will be much more convenient to use than remembering 3 or 4 pseudo-secret questions and a complex password. Given greater convenience and the protection of our money, it’s hard to imagine any sane people not going for this.

On the other hand, to quote Tommy Lee Jones in Men in Black:

“A person is smart. People are dumb, panicky dangerous animals and you know it.“

And those people believe biometric systems will prompt muggers to cut off fingers to access the nearest ATM, and that secret government organizations will use those eye scans to scan their minds from orbiting satellites and find out what color underwear they’re wearing (and who it really belongs to). So we can’t depend on reasoning with the people to get them to adopt biometric security.

It’s going to have to hit them in their wallet… and be convenient.

Companies will have to roll out systems on their own, not depend on people to go out and get them. Companies will have to offer significant incentives for using the new systems, like sizeable discounts on goods and services (or the avoidance of paying some sort of “security tax” to insure their transactions). Systems will have to be dead-easy to install and use, quite literally plug-and-play for the consumer. And once it’s in, it must be fast and easy to use, no hoops to jump through for every transaction (or even to set up a new account with biometric protection).

All of this, and reinforcing how much money we are saving, and how much more secure we are by using biometric systems, is what will do the trick.

Until and unless we do this, we can count on continuing to be robbed by hackers out of our reach to stop or punish, and watching our money siphoning into offshore accounts. It’s completely up to us to protect ourselves and our property.

May 26, 2015

NOTE: New domain name

http://RightBrane.wordpress.com has been redirected to the new http://StevenLyleJordan.wordpress.com. The redirect will stay in place for a year, and all internal links should also redirect to the pages in the new domain. In the meantime, you may want to change any bookmarks for this site to reflect the new site name. (If you follow this blog via email, you’ll need to renew by clicking on the new follow button.)

May 23, 2015

The Book Industry’s Discrimination Problem

Brooke Warner is publisher of She Writes Press and founder of Warner Coaching Inc. In this article, she calls out the openly and blatantly discriminatory practices against independent publishers in the established book industry, and the disservice being done to all of us.

Brooke Warner is publisher of She Writes Press and founder of Warner Coaching Inc. In this article, she calls out the openly and blatantly discriminatory practices against independent publishers in the established book industry, and the disservice being done to all of us.

As a country, we grapple with more than our share of discrimination challenges–where people of color, LGBTQ folks, and people with disabilities (to call out only a few of the bigger groups) feel its blow every single day. And while it’s frustrating at best, and often devastating, at least there’s a dialogue about it, and at least you can find outrage if you’re looking for it.

In book publishing, however, there’s a sanctioned discrimination against authors who subsidize their own work, and if people even bother to acknowledge it, few seem to be outraged. It’s upsetting because publishing folks are generally pretty liberal people–not the kind to condone discrimination in any form. Discrimination, however, is at its worst and most insidious when it’s sanctioned–and exacerbated when the perpetrators are justifying it as okay, business as usual, and just the way things are.

May 19, 2015

Ya gotta play to win

Last weekend I came across a series of blog posts by author Delilah S. Dawson about author self-promotion; and, as an author who has been trying to crack self-promotion for years, naturally I decided to read her posts. I started with Please shut up: Why self-promotion as an author doesn’t work, and without recapping everything in there, I’ll just say my takeaway was that Delilah’s secret to writing success boils down to one thing.

Last weekend I came across a series of blog posts by author Delilah S. Dawson about author self-promotion; and, as an author who has been trying to crack self-promotion for years, naturally I decided to read her posts. I started with Please shut up: Why self-promotion as an author doesn’t work, and without recapping everything in there, I’ll just say my takeaway was that Delilah’s secret to writing success boils down to one thing.

Unfortunately, that thing is luck. Blind, steenkeeng luck.

In her post, she outlines why social media does so little-to-nothing to sell books, and I found I couldn’t argue with a single one of her points (having seen them in inaction myself). Then she got around to describing what she sees as the writer’s formula for success… and it’s very telling:

The recipe seems to be GREAT BOOK + HARD WORK + TIME + LUCK.

And the writer can only control three of those things.

What Delilah’s saying is that luck, the thing you can’t control, is a major factor in a writer’s success—and I might go so far to say that it is such a major factor that the equation should read:

(GREAT BOOK + HARD WORK + TIME) x LUCK

You math fans will understand right off what I did there, but for those who aren’t: “GREAT BOOK + HARD WORK + TIME,” the work, are all important; but all of them hinge on LUCK to succeed. With all that work, times zero luck, you will fail. Or, with very little work, but a whole lotta luck, you can succeed anyway. (Ask a Kardashian.) LUCK is the secret ingredient. And you’ll either get it, like the lucky few—or you won’t, like the unlucky many.

I mean sure, just like with the lottery, ya gotta play to win; and in writing, you play by being prepared if your lucky break happens. You have to have a good book, be prepared to impress the right people, know the right things to say. But being prepared only works if you get the chance to use it… if luck strikes.

Okay, that’s not entirely true. You actually can do things to increase your odds—like writing stories that an audience has already proven (by sales) that they want—or spending lots of money (if you’re lucky enough to have it) on promotional marketing—or utilizing influential contacts (if you’re lucky enough to have or cultivate them) to help promote you—etc. But you have to remember that all of these are only odds-improvers. The final win-lose scenario is still all up to blind, steenkeeng luck.

This is particularly disheartening for me because, for most of my life, well… my luck has usually been bad, and I’ve often squandered opportunities when it’s occasionally been good. But the cool thing about luck is, it really doesn’t work in streaks; it’s completely random. You might have 300 unlucky draws in a row before you have a good one… or it could come on your second draw. So you never know… you might not see a lucky break for years… or it might happen this Wednesday.

This is particularly disheartening for me because, for most of my life, well… my luck has usually been bad, and I’ve often squandered opportunities when it’s occasionally been good. But the cool thing about luck is, it really doesn’t work in streaks; it’s completely random. You might have 300 unlucky draws in a row before you have a good one… or it could come on your second draw. So you never know… you might not see a lucky break for years… or it might happen this Wednesday.

Now, if you accept that idea, then it puts the rest of your promotional efforts under a new perspective: You are now no longer actively doing anything to get discovered and hit it big in self-publishing; you are doing everything to be fully prepared if when if when luck strikes. It doesn’t exactly take the pressure off, but it does put your predicament in a more palatable place, and ought to make you feel a little better during those periods when nothing is happening for you. Honestly, it makes me feel better.

So the only question remains: If when if when luck strikes… will you be prepared?

If you’re wondering whether I’ll be prepared… well, no one wonders that more than I. But I’m working on it. Now that I know the score, I’m trying to make myself more prepared every day. And I’ll keep doing that until either I win… or I get tired of the steenking game and cash out.

May 17, 2015

Bike commuting to ease stress? We wish.

I mean, we really do. But to a recent Treehugger article advocating commuting by bicycle as a form of stress-relieving exercise, many bike commuters (me included) responded with warnings about the seriously stressful rides they endure to get to work and back.

I mean, we really do. But to a recent Treehugger article advocating commuting by bicycle as a form of stress-relieving exercise, many bike commuters (me included) responded with warnings about the seriously stressful rides they endure to get to work and back.

Though the responses at the Treehugger site were light, the responses on Treehugger’s Facebook page were more illuminating. Riders complained about anti-bike car drivers, bad roads, lack of bike lanes or road-sharing arrangements, and lack of office clean-up facilities (or just plain hard weather) as highly-stressful biking realities.

I admit to similar feelings, in the supposedly bike-friendly Washington, DC. Despite the (sporadic) evidence of bike lanes in the city, in fact few of them are safe, mainly because very few of them are physically separated from the main roads; and drivers of every motor vehicle regularly ignore the unseparated lanes, block them during loading, cut across them while turning without looking for bikes, or use them to park or double-park. My ride to work, which consists of 50% (all unseparated) bike lane roads, might as well be on roads with no bike lanes at all, given the total lack of consideration and attention given to the lanes that are there.

I admit to similar feelings, in the supposedly bike-friendly Washington, DC. Despite the (sporadic) evidence of bike lanes in the city, in fact few of them are safe, mainly because very few of them are physically separated from the main roads; and drivers of every motor vehicle regularly ignore the unseparated lanes, block them during loading, cut across them while turning without looking for bikes, or use them to park or double-park. My ride to work, which consists of 50% (all unseparated) bike lane roads, might as well be on roads with no bike lanes at all, given the total lack of consideration and attention given to the lanes that are there.

And on this last Friday, which happened to be National Bike to Work Day, things were even worse. Extra traffic in Washington significantly increased the amount of bike lane blocking and ignoring throughout the city. I’m sure many a Washingtonian who decided to try out bike commuting on National Bike to Work Day found many a reason not to continue the practice on Monday.

And as bad as Washington can be, my suburb of Germantown, MD is even worse, having fewer bike lanes (all shared with cars or pedestrians), and a culture of drivers who pay more attention to their cellphones than their surroundings, jump lights, make turns without looking or signalling, wander across lanes and make sudden “confusion” stops with no warning or hazard lights used. Honestly, I’ve had more close calls in a week of Germantown bike riding than I have in a month of riding half the distance in Washington.

So, as much as I (and many others) would like to advocate bike riding to work, the reality is that most major cities and outlying areas are simply not configured for safe bike riding, and need serious improvement done to make bike riding a viable commuting option for all but the most brave, vigilant and dedicated bikers. Clearly marked and separated lanes, better intersections (with bike crossing signals) and clean, well-maintained roads are essential. Workplaces should also make sure bikers have a safe place to store their bikes and a place to change or clean up after a ride if needed.

So, as much as I (and many others) would like to advocate bike riding to work, the reality is that most major cities and outlying areas are simply not configured for safe bike riding, and need serious improvement done to make bike riding a viable commuting option for all but the most brave, vigilant and dedicated bikers. Clearly marked and separated lanes, better intersections (with bike crossing signals) and clean, well-maintained roads are essential. Workplaces should also make sure bikers have a safe place to store their bikes and a place to change or clean up after a ride if needed.

Most importantly, drivers need to be cognizant of bikers and accept them as roadway sharers, not as interlopers, and drive appropriately and alertly.

And as the future progresses, and we see self-driving automobiles joining drivers on the roads—and possibly, ultimately, replacing human drivers—it will be even more important to make sure bicycles will be safe sharing the roads with self-driving cars and pedestrians. There’s a lot at stake, and so many ways in which we could get it wrong. We need to work with more dedication to getting it right.

Bike commuting to ease stress? We wish.

I mean, we really do. But to a recent Treehugger article advocating commuting by bicycle as a form of stress-relieving exercise, many bike commuters (me included) responded with warnings about the seriously stressful rides they endure to get to work and back.

I mean, we really do. But to a recent Treehugger article advocating commuting by bicycle as a form of stress-relieving exercise, many bike commuters (me included) responded with warnings about the seriously stressful rides they endure to get to work and back.

Though the responses at the Treehugger site were light, the responses on Treehugger’s Facebook page were more illuminating. Riders complained about anti-bike car drivers, bad roads, lack of bike lanes or road-sharing arrangements, and lack of office clean-up facilities (or just plain hard weather) as highly-stressful biking realities.

I admit to similar feelings, in the supposedly bike-friendly Washington, DC. Despite the (sporadic) evidence of bike lanes in the city, in fact few of them are safe, mainly because very few of them are physically separated from the main roads; and drivers of every motor vehicle regularly ignore the unseparated lanes, block them during loading, cut across them while turning without looking for bikes, or use them to park or double-park. My ride to work, which consists of 50% (all unseparated) bike lane roads, might as well be on roads with no bike lanes at all, given the total lack of consideration and attention given to the lanes that are there.

I admit to similar feelings, in the supposedly bike-friendly Washington, DC. Despite the (sporadic) evidence of bike lanes in the city, in fact few of them are safe, mainly because very few of them are physically separated from the main roads; and drivers of every motor vehicle regularly ignore the unseparated lanes, block them during loading, cut across them while turning without looking for bikes, or use them to park or double-park. My ride to work, which consists of 50% (all unseparated) bike lane roads, might as well be on roads with no bike lanes at all, given the total lack of consideration and attention given to the lanes that are there.

And on this last Friday, which happened to be National Bike to Work Day, things were even worse. Extra traffic in Washington significantly increased the amount of bike lane blocking and ignoring throughout the city. I’m sure many a Washingtonian who decided to try out bike commuting on National Bike to Work Day found many a reason not to continue the practice on Monday.

And as bad as Washington can be, my suburb of Germantown, MD is even worse, having fewer bike lanes (all shared with cars or pedestrians), and a culture of drivers who pay more attention to their cellphones than their surroundings, jump lights, make turns without looking or signalling, wander across lanes and make sudden “confusion” stops with no warning or hazard lights used. Honestly, I’ve had more close calls in a week of Germantown bike riding than I have in a month of riding half the distance in Washington.

So, as much as I (and many others) would like to advocate bike riding to work, the reality is that most major cities and outlying areas are simply not configured for safe bike riding, and need serious improvement done to make bike riding a viable commuting option for all but the most brave, vigilant and dedicated bikers. Clearly marked and separated lanes, better intersections (with bike crossing signals) and clean, well-maintained roads are essential. Workplaces should also make sure bikers have a safe place to store their bikes and a place to change or clean up after a ride if needed.

So, as much as I (and many others) would like to advocate bike riding to work, the reality is that most major cities and outlying areas are simply not configured for safe bike riding, and need serious improvement done to make bike riding a viable commuting option for all but the most brave, vigilant and dedicated bikers. Clearly marked and separated lanes, better intersections (with bike crossing signals) and clean, well-maintained roads are essential. Workplaces should also make sure bikers have a safe place to store their bikes and a place to change or clean up after a ride if needed.

Most importantly, drivers need to be cognizant of bikers and accept them as roadway sharers, not as interlopers, and drive appropriately and alertly.

And as the future progresses, and we see self-driving automobiles joining drivers on the roads—and possibly, ultimately, replacing human drivers—it will be even more important to make sure bicycles will be safe sharing the roads with self-driving cars and pedestrians. There’s a lot at stake, and so many ways in which we could get it wrong. We need to work with more dedication to getting it right.

May 15, 2015

A bolder prediction

Ginni Rometty, the chairman and CEO of IBM, spoke about the future of artificial intelligence at the World of Watson event, designed to showcase the “ecosystem” of innovation happening around Watson, IBM’s signature artificial-intelligence system.

Ginni Rometty, the chairman and CEO of IBM, spoke about the future of artificial intelligence at the World of Watson event, designed to showcase the “ecosystem” of innovation happening around Watson, IBM’s signature artificial-intelligence system.

“In the future, every decision that mankind makes is going to be informed by a cognitive system like Watson,” she said; “and our lives will be better for it.”

Business Insider calls it a “bold prediction.” I don’t think so. I’ll go Rometty one better:

In the future, mankind’s most important decisions will be made by informed, cognitive systems like Watson, and our lives will be better for it.

Why isn’t Rometty’s comment “bold”? Businesses and businesspeople use information from computers to inform their decisions all the time; this statement just suggests they’ll be using more advanced systems, like Watson, in the future. Nothing bold about that.

It’s also not particularly game-changing. Even with the best of information, people still make the final decisions… and in doing so, they often ignore the best information and go with more emotional feelings, compassionate responses, “gut reactions,” etc. Which is sometimes just fine: Emotional or compassionate decisions can make things easier for employees, or make products more enticing for customers, which sometimes even improves the bottom line.

But if you think about it, the more advanced systems like Watson, and whatever its progeny will be, should be able to incorporate most of the more “human” concepts of compassion, a basic understanding of human emotion, and even weigh subjective data to better inform its decisions. At that point, human decisionmakers should reach a point where they are confident enough to accept the system’s decision without second-guessing it, and take the position of organizing the follow-through on the decision.

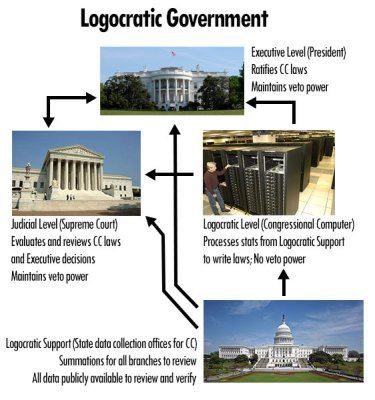

This is where I see the future of computing developing, and why I’ve advocated for a Logocracy that would utilize just such a system to make major decisions and pass laws as a major component of the U.S. federal government. The Logocratic arm of the government—let’s call it WatsonII— would essentially replace the Legislative arm, aka Congress… or, more accurately, place congressional staffers in the position of gathering data from their states and inputting it into WatsonII. WatsonII would process the data from each state and municipality and writing laws based on the idea of improving the health, welfare and spirit of the American people. The laws would be reviewed by the Executive and Judicial branches, as they are now, with veto power still held by the President and the courts (though WatsonII would supposedly know the law well enough that it would very rarely make new laws that would be considered unconstitutional).

This is where I see the future of computing developing, and why I’ve advocated for a Logocracy that would utilize just such a system to make major decisions and pass laws as a major component of the U.S. federal government. The Logocratic arm of the government—let’s call it WatsonII— would essentially replace the Legislative arm, aka Congress… or, more accurately, place congressional staffers in the position of gathering data from their states and inputting it into WatsonII. WatsonII would process the data from each state and municipality and writing laws based on the idea of improving the health, welfare and spirit of the American people. The laws would be reviewed by the Executive and Judicial branches, as they are now, with veto power still held by the President and the courts (though WatsonII would supposedly know the law well enough that it would very rarely make new laws that would be considered unconstitutional).

And though the idea would meet initial resistance, because, humans, I further predict that WatsonII-type systems will first be seen making everything from major corporate decisions to lesser personal decisions; and do them well enough that the public’s present resistance to being told what to do by a computer (as opposed to a boss, a politician or a talking head on TV) will soften and eventually relent. Eventually, computers will have the chance to prove that they will be better decisionmakers in major tasks than us. And we’ll be okay with that.

What a bold world that will be.

May 14, 2015

Radio Shack closes out the era of DIY electronics

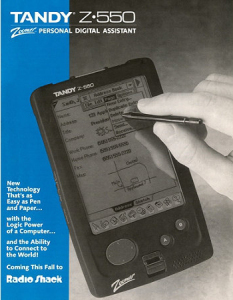

First, the full disclosure: I was a Radio Shack aficionado. I loved the place. Growing up, I used to visit my local store in Wheaton, weekly at least, to buy self-assembly electronics kits, shop for electronics parts, buy books on electronics, buy radios, tape recorders, speakers, battery chargers, my first PDA (Radio Shack’s rebranded Casio Zoomer), and just check out the cool stuff everywhere. I used to joke that any small town my family visited wasn’t civilized unless it had a Radio Shack in it. (“Look, there’s the Radio Shack! It’s a real town, all right!”)

First, the full disclosure: I was a Radio Shack aficionado. I loved the place. Growing up, I used to visit my local store in Wheaton, weekly at least, to buy self-assembly electronics kits, shop for electronics parts, buy books on electronics, buy radios, tape recorders, speakers, battery chargers, my first PDA (Radio Shack’s rebranded Casio Zoomer), and just check out the cool stuff everywhere. I used to joke that any small town my family visited wasn’t civilized unless it had a Radio Shack in it. (“Look, there’s the Radio Shack! It’s a real town, all right!”)

My love of electronics and computers came from Radio Shack. My serious consideration of getting an electrical engineering degree came from my association with the Shack (boy, how I wish I’d figured out how to follow that through!).

Now, I don’t visit Radio Shacks often… and neither does anyone else. Which is why the original owners declared bankruptcy, the chain has just been sold in auction to another company, and its future as a store and chain is very much up in the air.

What is not up in the air is this: Radio Shack’s original purpose—as a place for America’s electronics enthusiasts and hobbyists to buy, build and learn about radios, electronics and other related gear—has effectively come to an end. The American DIY electronics era, and its designated street-corner shrine, is done.

When Radio Shack started in 1921, radio itself—hell, electronics itself—was new. We were in an era of vacuum tubes, condensers and transformers the size of your fist, and radio sets the size of a loveseat. It was a new frontier, and in the 40s, the postwar hobbyist saw amazing fun and potential in the new field, a field that would let you speak to people across the planet, create cool household gizmos with pre-prepared kits, and even augment or just plain beef up the gadgets appearing on your store shelves.

One of the first PDAs–the precursor to the smartphone–and the Shack had it. (So did I.)

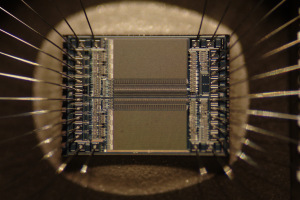

The creation of the transistor, and not long after, the integrated circuit (IC), opened up even more incredible possibilities for hobbyists, and brought more people into the Shack, especially to introduce their kids to things like the 150-in-1 electronics kit, the self-assembled desktop radio and more tiny doo-dads than you could shake a charge card at. Radio Shack also introduced many people to their first tape recorder, their first portable radio, their first Walkman, their first computer and, finally, their first cellphone. I got my first taste of a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA, the precursor to the blackberry and the smartphone, pictured at right), and I actually wrote my first novel on it! But it was the do-it-yourself market where the Shack really shone.

But as electronics have continued to shrink, devices have gotten cheaper and integrated with whatever was The Next Big Feature, the American pastime of repairing, rebuilding and repurposing electronics has waned through the 21st century. No one repairs a cellphone or radio any more; most of the time, not only is it physically impossible to do so, but it would “break your warranty” (the industry’s favorite phrase to convince you not to mess with your own stuff); so they literally throw it away and buy the latest one with the Gorilla Glass screen.

The products it sells have lost most of their luster as well; Radio Shack is no longer the first place to go for quality electronics… in fact, it’s usually pretty low on consumers lists, typically ranking evenly alongside 5-and-dimes and Wal-Mart.

When electronic circuit-building largely became inaccessible to hobbyists.

And the Shack’s position as the great local place to get information about electronics has been usurped by the web. The highly social environment of users supported by their local electronics expert has eroded, as Shack personnel have become less and less expert about electronics and more expert about selling batteries and phone plans. It’s become much easier getting the info you need by Googling or checking out a user group.

Radio Shack was truly a 20th century American icon, made for the modern “We can do it” aesthetic. But now that 21st century America is in a “We don’t know (or care) how it works anyhow” mode, there is no room for Radio Shack. It’s future is most likely to be a place to buy cellphones, and to serve those whose closest brush to DIY is to run a new cable from the smart TV to the DVD player.

Should we mourn Radio Shack, then? Not really; The Shack served its 20th century purpose, providing a service to enthusiasts and sending many a boy and girl into an electronics career. But our technology has moved past the Shack and largely removed its original purpose.

So, maybe we should instead mourn the loss of the people who frequented it: Those who liked building with their hands, troubleshooting and fixing their own problems; who were willing to make what they wanted, if they couldn’t find it on a store shelf; and who desperately wanted to know how the Next Big Thing worked… and if they could be in on it with both hands. There are still a few people like that out there. But now, they’ll have one less place to get together.

May 4, 2015

Should I stay or should I go?

Insert white hair here.

I’m in a bit of a conundrum, here; so I thought I’d just write out what I’m conundrumming about, to see if it’ll help me un-conun… dr… um…

Basically, I’m trying to decide whether to attend the 1-day UpublishU conference at the BEA Book Expo at the end of May.�� And right now, I’m having a very hard time justifying the trip.

It’s no secret (because I tend to tell people at the drop of a hat) that my writing career has so far been an initial 2 years of whoo-hoo good times, followed by 13 years of crashed, burned and zombie-fied.�� I’ve sought to re-animate myself by researching and trying out every marketing idea I could reasonably do, given no advertising budget and no contacts or connections to help forward my cause or promote me.�� But so far, nothing has worked.�� I’m presently holding out more hope for success from weekly plays of Powerball.

When I’ve tried to ask others what to do, I’ve mostly gotten advice that amounted to little more than platitudes���”If what you’re doing is wrong, it’s because you haven’t gotten it right”���”If what you’re doing isn’t working… keep doing it and someday it will”���”you can’t win if you don’t play”���or ideas that depend on the aforementioned contacts, connections or deep pockets that I, also-aforementioned, don’t have.

The UpublishU program says that it is for authors who have self-published but want to learn how to reach more readers, which I consider myself to be.�� However, another thing that I am, is a wall-flower: I am quiet, passive and unassuming, not forward or gung-ho.�� In a crowded room, I tend to shrink to the back or hide in the middle of the crowd; when people are trying to get help or ask questions from a source, I tend to end up watching from the sidelines, not stepping forward and pressing my own agenda.

In short, I am a social and professional milquetoast; and if my gaining useful information or making contacts means stepping past the crowd, inserting myself to the front of the line and dominating the conversation, you can be sure I’ll be elsewhere, wondering if there’s a Starbucks nearby.�� (I also base this expectation on my past behavior at other conferences where, despite my best intentions, I generally end up doing an uncanny impression of the invisible man.)

And this is why I fully expect that I will walk into the conference hoping to make some connections and, barring an outright holy-choir-singing miracle, walk out empty-handed.

There is also a program, of course���various classes that will provide information on planning, production and marketing.�� I can, of course, attend any of them, and some of them sound like they will provide useful marketing information.�� But it will mostly be generic information, not tailored specifically to a guy who’s trying to sell serious science fiction ebooks to a largely and paradoxically science-averse public.�� I’ve been researching and following such generically-designed marketing advice for years, with so far no success.�� Do I really expect that I’m going to get the one or two pieces of generic advice that I’ve never heard before, and that applying them to my specific needs will actually work?�� I admit to having low expectations there.

On the other hand, it’s a Saturday conference… don’t have to take time off work for it… and it won’t exactly break my piggy bank to go, even if I stay overnight in NYC to do so.�� If I get nothing out of it, the most I’ve lost is $300 and a weekend.

So: After having said all that, I’m still undecided on whether I should stay or go.�� Is the risk of $300 worth the admittedly vague chance that I will get something useful from the conference that will actually move my writing career forward?�� Or am I better served spending that $300 on a fistful of Powerball tickets and a good meal with my wife?

So: After having said all that, I’m still undecided on whether I should stay or go.�� Is the risk of $300 worth the admittedly vague chance that I will get something useful from the conference that will actually move my writing career forward?�� Or am I better served spending that $300 on a fistful of Powerball tickets and a good meal with my wife?

Feel free to weigh in on my conundrum if you’d like.�� Keep in mind that the aforementioned platitudes are unnecessary, but concrete information, direction and tips are always welcome.

May 3, 2015

Our A.I. love/fright affair

Ever stop to think about humans’ state of affairs with artificial intelligence (A.I.)?�� It’s a lot like a girl who’s fallen in love with a charming, attractive man who is also a serial killer: She is aware that he is dangerous, maybe even lethal; but she forces herself to love him anyway, trusting that her faith in his inner goodness will win out in the end and not leave her in a shallow grave in little, hacked-up pieces.

Ever stop to think about humans’ state of affairs with artificial intelligence (A.I.)?�� It’s a lot like a girl who’s fallen in love with a charming, attractive man who is also a serial killer: She is aware that he is dangerous, maybe even lethal; but she forces herself to love him anyway, trusting that her faith in his inner goodness will win out in the end and not leave her in a shallow grave in little, hacked-up pieces.

Or, rather, that’s how our relationship with A.I. could be; in actual fact, we stay with A.I. because we need its help, but we expect it’s going to turn and hack us up any second now.

You want a great example of an A.I. that isn’t dangerous to us?�� Look at the movie Iron Man, and Tony Stark’s personal computer system: JARVIS.�� A full-on A.I.,��JARVIS is not only incredibly intelligent and capable, it can converse colloquially with Tony Stark (and, presumably, anyone else), and help them operate incredibly complex machinery.�� When Tony builds his second Iron Man suit,��JARVIS is installed inside, provides Tony with heads-up display of the suit’s vitals based on the needs of the moment, and controls many of its functions based on Tony’s verbal instructions.

You want a great example of an A.I. that isn’t dangerous to us?�� Look at the movie Iron Man, and Tony Stark’s personal computer system: JARVIS.�� A full-on A.I.,��JARVIS is not only incredibly intelligent and capable, it can converse colloquially with Tony Stark (and, presumably, anyone else), and help them operate incredibly complex machinery.�� When Tony builds his second Iron Man suit,��JARVIS is installed inside, provides Tony with heads-up display of the suit’s vitals based on the needs of the moment, and controls many of its functions based on Tony’s verbal instructions.

And at no time does Tony���or the audience���expect��JARVIS to blow a gasket and kill Tony while trapped inside his own suit.�� Why not?�� Is it because��JARVIS is so helpful?�� Is it because he has a soothing English accent?�� Is it because we haven’t seen��JARVIS do anything in three Iron Man movies to hurt anyone?

I guess I find it fascinating that, in the Iron Man movies, Tony Stark accomplishes almost everything with the help of JARVIS.�� But the audience���conditioned as we apparently are to distrust A.I. and expect it to eventually attack us���doesn’t rail against the idea that Tony’s A.I. is inherently good; nor does that audience condemn Tony for using and trusting it, or criticize and avoid the movies that show it.

In Avengers: Age of Ultron, Tony Stark and Bruce Banner try to create an army of peacekeeping robots capable of protecting humanity.�� Maybe because it’s Tony we’re talking about, the audience believes he could do it in a perfect world.�� But when they expose the robot program to an alien A.I., it becomes corrupted, and we get the familiar, age-old “A.I. wants to kill all humans” trope.�� (Another age-old trope: If we get it from aliens, it must be bad.)�� Which, in terms of the Marvel movies, brings us full circle from good A.I. to evil A.I.

When Ultron tries to create its ultimate vessel, an unstoppable robot form, we circle back: The vessel is exposed to JARVIS, and when it comes to life, it wants to help humanity.�� The Vision is born, with JARVIS controlling it, and it’s an A.I. on the side of good.�� The Vision works with the Avengers, and (spoiler alert) the Avengers win.�� In their wonderfully superheroish way, the Marvel movies have shown us that A.I. is not necessarily something to be afraid of.

When Ultron tries to create its ultimate vessel, an unstoppable robot form, we circle back: The vessel is exposed to JARVIS, and when it comes to life, it wants to help humanity.�� The Vision is born, with JARVIS controlling it, and it’s an A.I. on the side of good.�� The Vision works with the Avengers, and (spoiler alert) the Avengers win.�� In their wonderfully superheroish way, the Marvel movies have shown us that A.I. is not necessarily something to be afraid of.

So, okay, we’re talking about superhero movies, which (let’s face it) are easy to dismiss.�� But maybe if we had movies about A.I. that didn’t corrupt itself, that didn’t attack humans the minute it was free, that actually helped humans and became an indispensable ally to humans… maybe we’d see a slow change in humans’ attitudes towards A.I.

But wait: We have had such movies, all the way back to Forbidden Planet; Star Trek, Silent Running, The Iron Giant, 2010, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Aliens, Bicentennial Man, I Robot, Moon and other movies have given us benevolent A.I.

So why are we still so obsessed with Terminators?

So why are we still so obsessed with Terminators?

It all comes down to our dissatisfaction with present technology, our experiences with bad software, crashes and blue screens of death.�� Our technology is, quite simply, not robust, not reliable and not very intelligent.�� And if we judge the potential of A.I. against our present experiences, A.I. looks pretty bad.�� The Terminator is our imaginary extension of today’s buggy and unreliable technology, taken to its nightmarish extreme.

But it’s an unfair comparison.�� After all, A.I. is supposed to be able to transcend its programmers, in much the same way as an infant eventually transcends the instinctual programming of its brain and starts to develop on its own.�� A.I., by definition, will grow and improve over time.�� We can also expect our technology to improve, as it has (no really, it has) for decades now.�� The hardware and software in future A.I.s should be as far advanced of the tech of today as a desktop computer is to the first LED watches of the seventies.

And as far as fearing A.I.s will attack us, that comes down to two human foibles: The fear of the unknown; and the anthropomorphic principle.�� Combined, it causes humans to see A.I. in competition with us, and fear that A.I. will be as evil and cruel as we humans are.

And again, we’re making a false comparison to ourselves.�� An A.I. will not have a pre-programmed survival instinct; since the A.I. can be easily backed up and replicated, the pressure of survival is effectively removed.�� And despite our low opinion of ourselves, there are actually many things that humans excel in… and because there are so many of us, there’s no reason not to take advantage of intelligent help.�� It would be in an A.I.’s best interest to work with humans to improve the lot of every living (and artificial) thing on the one planet we all live on.�� After all, a well-running environment is one in which A.I. can expand and thrive.

(And I’ve said before that an A.I. will probably be able to convince us to take any action that will be in its best interest, simply due to its knowledge of human nature.�� At the very least, it will know how to bribe individuals to do what it wants… for the bulk of the population, free porn will probably be enough to do it.)

In life, people always worry about being in a situation where someone else is telling them what to do.�� I’m sure much of the apprehension regarding A.I. is that it will make us do weird and undesirable things.�� But in reality, people do weird and undesirable things every day, often at the behest of a parent, a civic leader, a priest… because they have been convinced by that recognized authority that what they are being asked to do, however strange or undesirable, are good and valuable to humanity and to themselves.

I think an A.I. will be perfectly capable of telling people what to do, and why they should do it, even if they don’t necessarily want to; in other words, why their instructions are for the good of humanity.�� And one of the ways they will make this okay for us, will be to assist us in daily tasks, running complex systems for us, keeping machines humming, and making sure our world functions as comfortably as possible.�� I am fully confident that a real A.I. would be capable of nothing less.

I am not afraid.�� I am fully prepared to embrace A.I., even if it evolves to be our robotic overlords.�� I’m pretty sure we’ll be better off either way.