Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 70

May 6, 2011

Family planning to end population growth

For years, I've maintained that one of the greatest obstacles for humanity's future lies in reducing humanity's number; that people are simply too numerous to continue their present rate of consumption of food and materials to allow a sustainable planet. I have said that, instead of allowing the population to increase, we should be decreasing it, ideally to pre-industrial levels (yes–not billions, but millions), which would allow plenty of our mother planet's resources to go around.

Robert Engelman, Vice president for programs at the Worldwatch Institute, has provided a great deal of material to back up that premise, in his article on the Solutions website. An End to Population Growth: Why Family Planning Is Key to a Sustainable Future provides great detail on the studies done to establish the need for negative population growth to allow planetary sustainability, and the extent to which worldwide family planning efforts, and the availability of reliable contraception, could reverse population growth within a single generation.

In early 2010, researchers with the Futures Group in Washington, DC, estimated the demographic impact of meeting unmet family-planning demand in 99 developing countries and one developed one… Using accepted models for the impact of rising contraceptive prevalence on birthrates, the researchers concluded that satisfying unmet need for contraception in these 100 countries—with a cumulative 2005 population of 4.3 billion—would produce a population of 6.3 billion in 2050. Under the United Nations' medium projection, the countries' population would be 400 million higher, at 6.7 billion. Average global fertility at midcentury would be 1.65 children per woman, well below the population replacement fertility level—and would continue to fall.

Much of the data is based on the idea that unintended pregnancies worldwide are so greatly contributing to population growth that preventing the majority of those alone would allow families to largely continue their present rate of intended births, and still the overall population would decline. Further education could result in families deciding on fewer children (mainly as a reflection of hard times convincing them to limit children and avoid overtaxing the family resources), further reducing growth.

Engelman's article suggests that no authoritarian controls would be necessary to limit population growth; he clearly believes in the power of education (not to mention an industrial complex providing worldwide contraception tools to all sexually-active women) to bring about significantly fewer births and bring population down of its own accord. But that could be a tough nut to crack, for two reasons, both having to do with education.

Historically, women would self-apply contraception measures (or infanticide) when times were hard, and there was no telling when they'd get better. Today, it's incredibly difficult to convince women in developed countries that times are, indeed, "hard." With the availability of things like credit and government assistance, even the worst of times aren't as bad as what people used to have to go through even a century ago. This is possibly the primary reason why the United States is the most populous of developed countries at the moment.

Another strategy employed by women in undeveloped countries has been to have a number of children, because infant mortality was always high. Although infant mortality is dropping significantly today, thanks to the help from developed countries, women have not altered their childbirth habits significantly, and families are becoming larger on average in undeveloped areas.

Both of those educational chasms must be bridged, before we can expect to see significant changes in birthrates and contraception use among sexually-active females. And it wouldn't hurt to get sexually-active males on-board as well. And even beyond the educational divide, the task of providing contraception supplies to all those women, while not impossible, would be a monumental task.

It may be highly debatable how realistic or potentially effective the premise is. But I would say it sounds worth pursuing with all fervor.

Family Planning to End Population Growth

For years, I've maintained that one of the greatest obstacles for humanity's future lies in reducing humanity's number; that people are simply too numerous to continue their present rate of consumption of food and materials to allow a sustainable planet. I have said that, instead of allowing the population to increase, we should be decreasing it, ideally to pre-industrial levels (yes–not billions, but millions), which would allow plenty of our mother planet's resources to go around.

Robert Engelman, Vice president for programs at the Worldwatch Institute, has provided a great deal of material to back up that premise, in his article on the Solutions website. An End to Population Growth: Why Family Planning Is Key to a Sustainable Future provides great detail on the studies done to establish the need for negative population growth to allow planetary sustainability, and the extent to which worldwide family planning efforts, and the availability of reliable contraception, could reverse population growth within a single generation.

In early 2010, researchers with the Futures Group in Washington, DC, estimated the demographic impact of meeting unmet family-planning demand in 99 developing countries and one developed one… Using accepted models for the impact of rising contraceptive prevalence on birthrates, the researchers concluded that satisfying unmet need for contraception in these 100 countries—with a cumulative 2005 population of 4.3 billion—would produce a population of 6.3 billion in 2050. Under the United Nations' medium projection, the countries' population would be 400 million higher, at 6.7 billion. Average global fertility at midcentury would be 1.65 children per woman, well below the population replacement fertility level—and would continue to fall.

Much of the data is based on the idea that unintended pregnancies worldwide are so greatly contributing to population growth that preventing the majority of those alone would allow families to largely continue their present rate of intended births, and still the overall population would decline. Further education could result in families deciding on fewer children (mainly as a reflection of hard times convincing them to limit children and avoid overtaxing the family resources), further reducing growth.

Engelman's article suggests that no authoritarian controls would be necessary to limit population growth; he clearly believes in the power of education (not to mention an industrial complex providing worldwide contraception tools to all sexually-active women) to bring about significantly fewer births and bring population down of its own accord. But that could be a tough nut to crack, for two reasons, both having to do with education.

Historically, women would self-apply contraception measures (or infanticide) when times were hard, and there was no telling when they'd get better. Today, it's incredibly difficult to convince women in developed countries that times are, indeed, "hard." With the availability of things like credit and government assistance, even the worst of times aren't as bad as what people used to have to go through even a century ago. This is possibly the primary reason why the United States is the most populous of developed countries at the moment.

Another strategy employed by women in undeveloped countries has been to have a number of children, because infant mortality was always high. Although infant mortality is dropping significantly today, thanks to the help from developed countries, women have not altered their childbirth habits significantly, and families are becoming larger on average in undeveloped areas.

Both of those educational chasms must be bridged, before we can expect to see significant changes in birthrates and contraception use among sexually-active females. And it wouldn't hurt to get sexually-active males on-board as well. And even beyond the educational divide, the task of providing contraception supplies to all those women, while not impossible, would be a monumental task.

It may be highly debatable how realistic or potentially effective the premise is. But I would say it sounds worth pursuing with all fervor.

May 5, 2011

Stores blocking ebooks? Try selling them instead

John Blake at the Bookseller Blog laments over ebook sales cannibalizing hardback sales, what he calls "real books," in the stores:

The idea of simultaneously publishing an exciting new title both as a hardback and as an e-book seems totally crazy. If only publishers could publish the book as a hardback initially, then put out the e-book some months later, bookshops would be given a sporting chance to stay in business, and the dizzying decline of book sales could almost certainly be slowed.

I was fascinated to discover that serious readers—people who buy more than 12 books a year—are fast becoming the keenest e-book customers. These, surely, are the very people who would wish to purchase hardbacks rather than waiting months for an e-book edition.

Obviously Blake considers ebooks inferior to hardbacks—an attitude that many of his blog's commenters clearly disagreed with—and seems to think he's found a way for bookstores to survive, namely, by holding back the increasingly more popular ebook to prop up the decreasingly popular hardback, which he sees as the way to save the bookstore.

As usual, everyone is ignoring the obvious: Selling ebooks at the bookstore. The idea is hardly new, and it only requires a store to have an online presence for its walk-in customers. Hardback books can serve as "display models," allowing customers to get a look at the contents. Then they can whip out their favorite reading device and buy the book from the store's portal, or pay for the book at the cashier and have the staff email the file to them.

This way, you can sell both products at the store, whichever customers prefer… and since many of us have no interest in buying hardbacks at any price, despite Blake's obvious disbelief in such an idea, it means more selling opportunities for the store. I know it would give me a reason to go back, as I haven't bought a printed book in years, and have less and less of a reason to go into a bookstore (the last two times I went, I came out with music CDs… no books).

Barnes & Noble is a good example of this practice, allowing customers to buy via their in-store portal (though ebooks don't usually come out at the same time as printed books yet, simultaneous releases are starting to happen with many books). Put simply, it's a practice every store ought to be applying, which will simultaneously allow them to trim down to more sustainable sizes to befit the modern era of bookselling.

Or they can continue to try to block progress, and see where that gets them.

May 4, 2011

When will showing off get us practical electrics?

Peugeot recently showed off its EX-1 concept electric car for its 200th birthday. A 100% electric car, its main claim to fame—besides that Batmannish shell—is its 340 horsepower engines and its breaking of six world records. (I understand it may have also taken the record for the Kessel Run from the Millennium Falcon, but that hasn't been confirmed.)

Peugeot recently showed off its EX-1 concept electric car for its 200th birthday. A 100% electric car, its main claim to fame—besides that Batmannish shell—is its 340 horsepower engines and its breaking of six world records. (I understand it may have also taken the record for the Kessel Run from the Millennium Falcon, but that hasn't been confirmed.)

The EX-1 is a vehicle to stand beside the Tesla Roadster, which does 0-60 in 3.7 seconds. Maybe that'll be fast enough to save you from the authorities, or your wife, when they find out you paid over $100,000 for it.

It's great seeing all of this effort being taken to create scare-your-grandmother electric speed-demons. Really, it is. After all, this world needs all the 200+ MPH vehicles it can get, right? Traditionally, car companies create racers and concept cars in order to garner intense interest in the brand, which in turn raises stock prices and makes the company more money. In turn, the company trickles-down the technology in their racers and prototypes to the real car market. Much of the equipment inside even stodgy station wagons and tiny economy cars owe their heritage to racing tech.

Unfortunately, these companies don't seem to be making much progress getting to market the 200+ mile range electric car that Mr. and Mrs. Joe Consumer is looking for. You know, the one that doesn't cost over $100,000… and comes with a radio.

For instance, it's been recognized for most of a decade that pancake motors at each wheel are far lighter, more powerful and more responsive than one large motor and a transmission/differential system, would use less energy, travel further and would be easier to service. So where are the pancake motors on practical cars? Nowhere yet.

And where are the cars that look like… well, cars? Not everyone wants to buy a vehicle that looks like it just rolled off the Blade Runner lot. I want an electric car with handsome lines… not a lightcycle. And not one of those things the ghetto hamsters sell.

It's been my hope that, by 2015-2020, during which time I expect my current car to give up the ghost, I will have a number of full electric cars to choose from. Of course, in 1980 I saw electric concept cars about, built by small companies, and big ones like… yes, GM. I thought I'd see the practical electrics everywhere on the road in 2000. Thirty years after my initial guesstimate, ten years after the due date in my predictions, I'm still seeing a lot of concept cars.

It's time to move on from the concept stage. You've had 30 years; now give us practical cars.

May 1, 2011

What you want to get used to

One of the most spectacular characteristics of higher organisms is their capacity to rise above their instinctual programming and learn new things. The ability to learn, and to learn well, is often tied directly to survival success, or at least to level of prosperity. Humans have proven to be particularly adept at learning, and take full advantage of this tool in their struggle to get ahead in survival and non-survival situations.

One of the most spectacular characteristics of higher organisms is their capacity to rise above their instinctual programming and learn new things. The ability to learn, and to learn well, is often tied directly to survival success, or at least to level of prosperity. Humans have proven to be particularly adept at learning, and take full advantage of this tool in their struggle to get ahead in survival and non-survival situations.

Thanks to the wonderful plasticity of the human mind, an individual is capable of devoting varied amounts of its brain processing power on the subject of its choosing. If they choose to know just a little about a particular subject, only a small amount is retained. Yet, if they decide to know everything there is to know about a subject, the brain is capable of applying substantial information storage and processing capacity to that subject. This accounts for people who can carry encyclopedic knowledge about one subject—say, Star Wars—whilst simultaneously having incredibly minimal knowledge about another subject—say, girls. (I started off vowing not to use that particular analogy… but man, it was just too frakkin' easy…)

This mental talent extends to the physical, as well. This makes sense; the mind controls the body. Therefore, the mind is capable of teaching the body new tricks, practicing and honing certain reflexes, responses to certain stimuli, etc, designed to support that subject to which it has devoted so much processing power. This is what teaches a baseball aficionado to throw, hit and catch a ball, or a skater to perfect a pirouette. This is what taught me to type on a virtual keyboard on my first PDA, on a space that would not have held twelve keys of the Royal typewriter on which I learned to type in the first place.

Jordan's Theorem

For years I have had a mantra—and in the spirit of my writer-idol, Arthur C. Clarke, I tend to think immodestly of my mantra as Jordan's Theorem—that describes this phenomenon, to wit:

"You get used to what you want to get used to."

Though there are obviously exceptions to most every rule (or theorem), this one applies to most human effort applied to doing things.

I, of course, applied this principle often in life… for instance, when I taught myself the complex balancing skills needed to ride a bicycle… or the hand-eye coordination required to type on a keyboard… or the dexterity to cleanly crack and open an egg with one hand. In each case, I chose to hone a new skill that I desired to have, and kept working at it until I was proficient at it. As I have done these things, so I have seen others do similar things, providing proofs to my theorem every day.

I think of my theorem often, but most especially when I engage people in discussions of e-books for the first time. Such discussions often take familiar paths: After the establishment of whether or not the person actually knows what an e-book is, the response I hear the most often runs along these lines:

"Oh, I couldn't read on anything but a regular book. I don't like reading on computer screens. I like paper."

This is where the immodest portion of my mind jumps up and starts yelling and waving a massive banner, with Jordan's Theorem printed in radioactively-bright letters, in the forefront of my consciousness. Suddenly I feel the urge to engage that person, to attempt to explain Jordan's Theorem to them, and to convince them that if they were so inclined, of course they could learn to love reading on computer screens, or PDAs, cellphones, dedicated reading devices, even their iPod screen… all they had to do was want to do it.

Of course, it is considered impolite to actively try to convince another person that they may be wrong. So, out of a sense of politeness, I try to suggest that they may not have given e-books a fair try yet… that it might be better than they expect. The general response I receive from that runs along these lines:

"Electronic screens hurt my eyes. It's weird reading on a screen. I can't get comfortable reading on a screen. Don't make me hit you with this book."

(And for the record: No, I never get the "Hmm… that's an interesting point. Perhaps I shall try to check out some e-books, myself… and thanks so much for pointing them out to me!" response. Might be my approach.)

Jordan's Corollary

At this point, the immodest portion of my mind reaches down and grabs another banner, imprinted with what I refer to as the Corollary to Jordan's Theorem, which reads:

"If you won't get used to something, it is because you just don't want to."

Now, I realize that Jordan's Corollary to Jordan's Theorem has some decent-sized holes in it: For instance, a blind man can't learn to drive a car, no matter how badly he may want to. But in most cases, the corollary holds water, and in the case of probably 90% or more of people who haven't tried e-books, I consider it well-nigh watertight.

This is because, over the years, I have seen people teach themselves to do things that they were sure they would never be able to do… but once they decided it was in their best interests, they learned to do it, and to do it well. People have taught themselves how to work with computer programs, in order to do their jobs. People have learned how to properly write resumes, in order to get better jobs. People have learned to cook, in order to not starve when they moved out of their mother's house. People have learned to take public transportation, when driving to work became too slow, frustrating, expensive, or all of the above. Women have trained themselves to walk with an eye-popping sexy strut in 3-inch heels (trust me, no women born knows instinctively how to walk like that). People have learned to type messages on tiny Blackberry keyboards, despite the one-time universal belief that no one could ever use anything smaller than a full-sized Royal typewriter keyboard to type anything significantly longer than a shopping list.

And I have witnessed people who have said things like "I only like to read on paper," then checked out an e-book… usually because there was something about the e-book that drew them in, for instance, it was a book they wanted, or needed, that could not be found in print. Because they really wanted to read that book, they obtained the e-book, and taught themselves to get used to the differences between reading on paper and reading on an electronic screen. And lo and behold, eventually they found that they could read e-books as easily as reading printed books, and could even tune out the differences between paper and electronic formats and focus on the book itself.

So I firmly believe that most—not all, mind you, but most—of the people who provide reason upon reason why they can and will not read an e-book… have, in fact, already unilaterally decided that they will not like it, even if they have never tried it, and as long as they feel that way, e-books have no chance with them.

Method of attack… uh, I mean, "Encouraging people"

As a writer of e-books, obviously this concerns me. Not so much that I feel every e-book reader in the world should be reading my books… but because I'd like to see more e-book readers out there, and hopefully, the small proportion of those people who read my e-books would end up equating to a larger actual number (I am not being entirely altruistic here, I admit). So I have given plenty of thought about what to say to such people, to encourage them to see e-books in a new light, and to maybe see what they are missing.

So far, I have come up with a big goose's egg. Why? Because it's hard to convince someone of something against their will. If they have decided something is so, even showing them something is not so isn't always enough to convince them that it's not so. (Hmm… maybe I should consider that my corollary's corollary…) But I still find myself trying to assert Jordan's Theorem by convincing people they can learn to love e-books, if they just give them a chance.

Since the theorem suggests a psychological effect at work, I try to hit them in their psyche. But that can be an elusive target to hit. Some people will respond to reverse psychology: "Your loss, pobresito!" Others can be gotten to by appealing to their love of iconic personalities: "Girlfriend, Oprah loves 'em!" And some respond to basic peer pressure: "Everybody else is doing it…"

And sometimes, you have to bypass Psych 101, because some people are smart enough to know that's exactly what you are doing. So you have to use approaches that appeal to them more directly: "A $200 reader can hold thousands of dollars' worth of books." "Think of the shelf space you'll get back!" "Dude, Ashley loves 'em, and she was totally checkin' you out yesterday!"

Hey, whatever works.

Goals

The goal of any such effort is, of course, to get more people to read e-books. I realize that my effort won't work on everyone. But I try not to let those who are simply unwilling to try something new deter me from helping someone else who is more open to new things, and honestly doesn't know what they are missing.

The cool thing about psychology is, it's not absolute. Unlike many things in life that are not reversible, mental attitudes and desires can be reversed, given enough incentive to do so, and with enough help from interested parties. People can decide to change, just by… deciding. It really is that simple. Sure, the change itself will require more effort… but as I've said once or twice before, You get used to what you want to get used to.

So, until Jordan's Theorem gets completely busted, I will keep applying it wherever I can, using it as my guide to help those who continue to type on Royal typewriter keyboards, go to Mom's house for a decent meal, and read only printed books.

Scarcity to Abundance: E-books and the pain of the Digital Revolution

It has been baffling to many aficionados why the e-book market has taken so long to develop… isn't it as simple as opening up a new counter at the bookstore, or creating a new section of an online bookstore, and beginning to sell e-book content? Alas, e-books have proven to be much more than simply a new format for reading, as the constant banter over selling paradigms, formats, price, piracy and access have effectively demonstrated. E-books represent no less than a conceptual change to an entire world of literature, a foundation-shaking event that will eventually leave the industries devoted to literature forever changed. It is the real significance of the Digital Revolution: The fundamental difference between a commodity that was once scarce, and one that is now abundant.

Historically, any time a commodity undergoes a radical change in state, from scarcity to abundance—or vice-versa—all Hell usually breaks loose. Fortunes are lost and won. Political parties rise and fall. Paupers become princes. Princes become fools. Heads roll. The switch from scarcity of power to abundance, in the form of cheap coal, kicked off the Industrial Revolution, and the discovery of massive fields of oil further fueled it. The development from a scarcity of humans to an abundance forced sweeping changes in law and culture, and numerous scientific developments, in order to feed, clothe, house and care for billions of people concentrated into small areas.

At the same time, the evolution from an abundance of natural resources, to a scarcity of resources, such as fresh water, various foods and feed animals, have forced entire civilizations to alter their way of life to replace those resources, to conserve what was left, or to leave for better climes. An abundance of a particular skill, like expert furniture craftsmen, followed by a scarcity caused by increased demand, inspired machine design and factory production to take up the slack, forever altering the craft of furniture-making. None of these changes were quiet or easy, but they were essential to deal with the reality of change.

The evolution of the transistor, from scarcity to abundance, has brought the cost of computing down from hundreds of thousands of dollars in the mid-twentieth century, to a few-score dollars for the same computing power today, and put computers into the hands of the average person. The Digital Revolution, like the Industrial Revolution before it, has been driving change in many areas for roughly the past fifty years. And now, finally the Digital Revolution is making the same change to the lowly book.

The book evolves

What was once so rare and valuable that it had to be secured in private collections and libraries, loaned out in care and consideration, or copied and sold at whatever price the market would bear… is now virtually free to produce and disseminate. Literature, once limited to the physicalities of paper and the practicalities of transportation networks, can now be reproduced with captured electrons, and sent to the opposite ends of the world in seconds. Scarcity has been trumped by abundance. But the business of commodity-as-scarcity is still with us—and like the blaquesmith watching the automobile overtake his business, or the circus performer seeing his audience abandon him for television, the profiteers of traditional scarcity-based print publishing are dismayed at the future of the abundant digital book, and the almost incomprehensible impact it will have on their lives and fortunes.

If you examine most of the efforts expended by today's writers, publishers, booksellers and lawyers to deal with e-books, you quickly see that their efforts are primarily designed to create an artificial model of scarcity to fit the e-book into. Amazon's Kindle store, built around its dedicated readers and repackaged content, is a classic example of Industrial Revolution-era thinking: In many ways it is a sort of "bottled water" industry, created to Amazon's specifications, to insure they will retain the same control over e-books that they currently hold over printed books.

Fortunately (or unfortunately, in Amazon's case), savvy consumers are already recognizing the fallacies of this model, just as they have come to realize that "bottled water" is usually no better or healthier than what they can get out of their own tap, and a lot more expensive at that. Consumers are well aware that the water is still out there, flowing freely from streams and taps. E-books, like water, do not need to be packaged to be enjoyed… packaging only serves to create an Industrial Revolution-era paradigm that traditional capitalists can attempt to take advantage of.

E-books are a product of the Digital Revolution, and as such, are only being held back by Industrial Revolution paradigms. The realities of the digital world dictate that original creation is still work, but re-creation and delivery can be virtually effortless. Effortless re-creation and delivery means virtually-zero-cost, with a requisite loss of the need to recoup that cost… a factor that formerly needed to be added to the "cost" of any product. What's left is the value of the original work alone, freed from the extraneous costs of reproduction and distribution.

Hard change

During the period known as the Industrial Revolution, we were conditioned to pay for products like books based more on the costs of reproduction and redistribution than on the original creation. And producers were conditioned to run businesses and recoup profits based on those same realities. With those realities removed, how do we recondition the public to pay for the creation of literature, instead of the production and distribution of printed and bound copies? How do businesses generate income and profit? And how do we deal with the blatant inequalities of such a system that, until now, have gone largely ignored?

The institutions and conventions that our forefathers built around the precepts of the Industrial Revolution, appropriate and effective as they were for their day, must be revisited for the realities of the Digital Revolution and media like e-books. Buying and selling paradigms, and the role of the many facilitators of that process, need to be critically re-examined and reshaped to fit the demands of modern reality. Issues like copyright and ownership must also be revisited, as they have fallen so far behind the Digital Revolution as to be almost worthless today. Compensation for creations must be examined, and up-to-date determinations need to be made of who is responsible for compensating whom, and how that should be accomplished.

What does this mean for authors like me? I wish I knew. Hopefully, a way will be devised to fairly compensate writers for their work—for, after all, if writers feel they are not being treated fairly, can we expect them to write for us?—and creative works will be available to the public in the spirit of abundance. Quite possibly some type of minute charge, like an information tax, will be levied upon anyone who downloads an e-book, with some portion of that tax to eventually find its way into the author's pocket through a royalty system. Possibly governments will simply compensate authors for material entered into the information flow, paid for by more taxes and perhaps additional income for unusually popular works. Or perhaps some other method will be devised that we today cannot even imagine. For some authors, it might be enough to live off of. For others, perhaps the days of "making a living" as an author are over. But it may take generations to work it all out… so we may never know.

Evolution happens

The Digital Revolution, with its commodity-based shift from scarcity to abundance, will bring incredible and, in some cases, unrecognizable change to much of modern life… this is inevitable. Some of it will also be painful. The 20th century equivalents of the blaquesmith and circus performer must accept the fact that they will have to adapt, retire, or perish. But when we accept the realities of the Digital Revolution, and embrace the effort to develop new ways to work, to sell, and to profit, the eventual reward will be Earth-shattering.

The Digital Revolution provides us a unique opportunity to create a truly global marketplace out of the many disparate and uneven markets out there today. The effort to create a balanced, fair global market out of the chaos of Industrial Revolution-era international boundaries would be nothing short of apocalyptic… but imagine the reward of such an accomplishment. It would be one of the greatest, and most satisfying, challenges of the millennium. It must be addressed, if we as a global culture are ever to progress.

E-books are in a unique position of being able to stand at the forefront of the Digital Revolution, alongside digital music and other media. All digital media, in fact, share similar issues that must overcome the painful transition from scarce commodity to abundant commodity. But if those issues are overcome, they will be applicable to most other products of the Digital Revolution, smoothing the transition to other products, and aiding the development of whole new concepts of what a digital-era commodity is.

The state of our world, after the full adoption of the Digital Revolution, will likely be as unrecognizable to those of us alive today as the Industrial Revolution would have been to the farmers of the fifteenth century. The commerce of literature could also evolve into something we can barely understand today. But considering the value the world can derive, from a Digital Revolution poised to spread knowledge, entertainment and enlightenment around the world, who would we be to stand in its way?

Digital security: Think Biometrics

Ever since it was discovered that people could send information encased in arranged groups of electrons, a realization about the nature of that information began to set in: It was no longer as secure as it had been before.

Workable security for the American West.

Physical objects were easy to keep track of and catalog. They were harder to replicate, which made it easier to control their numbers. Large numbers were correspondingly harder to move, or lose, than smaller numbers. And they could be locked in a coherent space, with no chance of somehow seeping through the cracks and escaping. But the new digital file presented a problem that was as far beyond the constraints of physical objects, as a horse would be compared to a slug. And whereas you can confine a group of slugs with the simple expedient of encircling them with salt, you need a considerably more sophisticated method to corral a herd of horses.

Speaking of herds: In the early days of North American colonization, ranchers and farmers ran into problems establishing their lands, and keeping others' herds of cattle, horses, sheep, etc, off of farming lands. Over time, methods of fencing land, documenting property lines, branding animals and cataloging them with the local authorities were devised… and this, despite violent disagreement and joint animosity, in what was considered at the time a "lawless environment," that suggested that such control would never be accomplished. Bandits and rustlers regularly demonstrated that those controls could be broken, and often made others' lives miserable (and even shortened) in their acts of flaunting their ability to break the laws. But the steps were bolstered by law enforcement, and by a cooperative nature that forced farmers and ranchers to work together, or be denied fair commerce and other social perks over their transgressions, and soon, the bandits and rustlers were brought under control. In the end, the steps were seen as beneficial to all, as they provided security and protection fairly to those in the community, whilst allowing commerce and fair profit to be made.

There are a lot of similarities between today's digital document landscape, and the "lawless West" of the 1800s Americas. Before control was established on Westward Expansion, property was stolen, claims were jumped, herds of livestock were rustled and human lives were snuffed out by petty criminals, on a frighteningly regular basis. Despite the romanticism of the movies, there were no codes of conduct, there was only greed, anarchy, and the rule of the gun, the mob and the masked gang.

Today, computer bandits (usually called "pirates", but they might just as well be considered the modern version of "cattle rustlers") demonstrate every day that electronic files can be hijacked, security measures can be broken, and property can be stolen almost at will. And they, as well as others who have bought into the pirates' constant insistence that they cannot be stopped, believe that there will never be a way to provide security and protection for digital property. Anarchy exists today, and those who seek to establish any rule or control over their property are at the mercy of those who revel in lawlessness.

It is, of course, possible to find other ways to support digital content, such as through sponsoring programs, subscription models, and other pre-sale devices, thereby allowing for the files' free dissemination, and largely removing the need for security measures. Yet, despite the present reality, there are security measures that can be taken—some already developed, some under development, and some beyond the horizon—as well as changes to law enforcement and the social activities of individuals, to help provide the backing of that security and ensure its overall effectiveness.

Most of today's digital file security technology—aka Digital Rights Management, or DRM systems—are based on simple number- or text-based passwords, which are usually unique to the single item and therefore essentially disposable. The simple password systems are usually easy to break as well, leading eventually to potential dissemination of unprotected files. The fact that text-based passwords are so easy to circumvent, and that there is little disincentive to do so, makes existing DRM quite literally worthless… and this is the source of most of the anti-DRM sentiment in electronics circles. But there are better encryption methods available to digital files, methods that would make code guessing practically impossible. The most advanced and promising of these are biometrics.

The 21 st century "key": Biometrics

In the movie "The Incredibles," fashion designer Edna Mode provides some laughs when she enters her secret design lab by quickly and casually punching numbers into a keypad, providing a handprint, allowing her eyeball to be scanned and speaking into a voice recognition microphone (and just as quickly clearing Helen Parr, her guest, before she gets shot as an intruder).

A fingerprint scanner embedded into an electronic device, not much larger than the width of a finger.

Although the scene was comical, it hints at the future of security in the form of biometric identification systems, identification systems based on physical attributes that are unique to each individual. Many of the security methods in the Incredibles scene are already in use today, and others are still on the drawing boards. In fact, many biometric systems are now available as over-the-counter accessories for computer hardware, such as fingerprint ID scanners that can be used to log into a computer, or to unlock the files on a storage device such as a USB key. Such an encryption system would be orders of magnitude safer than mere text-based passwords, harder to spoof, and almost impossible to unintentionally share.

Although these devices are considered optional today, they are already being incorporated permanently into some devices being used in business circles (fingerprint ID scanners are now built into the bodies of many laptops). Businesses, ever mindful of security and seeking new and better ways of doing things, have usually been the first to experiment with these security devices. But, as has happened with other business-developed hardware and software, office-proven equipment could eventually find its way into the home. This could happen as other entities find uses for security hardware and software that benefits consumers.

We can easily envision an electronic landscape where every device capable of accepting a digital file, or for that matter needing any sort of personal security, is equipped with a fingerprint ID scanner (the smallest of them are about 1×2 centimeters in surface area). A user would activate the device by swiping their finger over the scanner, essentially replacing the "on" switch on most devices.

When a digital document was to be purchased, the purchaser would swipe their finger across their scanner for the purchase. Their scanned fingerprint data would be permanently encrypted into the document, and when the document was accepted or opened, the device would require a scan to decrypt and open it (probably the "on" scan would suffice, but a second verification scan might be useful). If the scan did not match the encryption password (the right biometric ID), the document would not open, or would not be accepted by the device at all.

Users would eventually adopt a new action, the "swipe," in their everyday dealings with protected electronics. The "swipe" would replace password typing, card-inserting, fob-waving and many other existing forms of initial electronics access, and would be added to individual files on an as-needed basis. If the system is kept relatively simple and accurate, the "swipe" could become second-nature in no time.

But how do consumers, who are notorious for not wanting to try radical new things, get into the use of biometric systems? And once in, how do they resist the urge to break them? The key, so to speak, is "incentive."

Incentives for new habits

In order to get people to try something new, you generally have to present them with a new way of doing things, show them how effective it is, encourage its use with appropriate incentives, and sit back while the population turns over. Most widespread changes are incorporated into daily use in this way.

A fairly recent example of this is the incredible proliferation of the cell phone, considered when it was introduced to be a rich man's toy that most people couldn't see any real need for. It was through incentive—subsidized phones, competitive prices and packages, cool designs and the usual "be cool with your friends/the opposite sex" ads—that cell phones became the runaway phenomenon of the 1990s and 2000s. Now, many cell phone users are cancelling their land-lines, something largely unheard-of just a decade ago, and leave their phones on at all times. A completely new paradigm of behavior was created in one generation, and many of us can scarcely imagine what life was like before the cell phone transformed our lives.

In another example, incentives such as online store discounts, exclusive content and advance opportunities at other offers and products have proven to be effective in encouraging customers to sign up for and use store and club cards, a system that uses security to ensure the customer gets deals that non-members cannot get. Interestingly, even though certain personal information is knowingly being collected, maintained, accessed by third parties and used to deliberately sell targeted products at the card owners… consumers largely accept all of this Big Brother-ish activity, for the perception of saving money.

Similar incentives could be applied to biometric systems, in effect, encouraging consumers to add the requisite hardware to their electronic devices, and to use it without fail on any device capable of reading a digital document. Unlike proprietary store cards, a biometric system would need to be standardized and widespread, applied equally to every electronic device that can accept external digital files. This would remove the danger that a vendor or company would fold and their proprietary biometric system would take valuable content with them… a major "disincentive" that is presently working to drive consumers away from proprietary systems.

In addition, a standardized way to encase the files within this encryption system would need to be devised. Protocols for assigning an encrypted "key" to a file, unlocking that file, and establishing fair use guidelines, would have to be established and followed. The methods of using these tools would have to be easy, almost thoughtless in their simplicity.

And finally, good reasons for using these tools, and good reasons not to abuse them, must be established. Access to exclusive content, discounts, convenience of use, and even social incentives (however real or bogus) should be used to drive consumers in the direction of biometric security systems. There should also be a significant downside to breaking or abusing these tools, as in a loss of access to other content, or having rights, privileges or accounts taken away… this disincentive method has been effective in keeping cable subscribers from sharing TV signals for years, and today is used effectively in preventing some software (like the Windows OS) from being shared on multiple computers.

Properly used, these tools enforce consumer honesty, with honest and dishonest alike, because of their desire to have access to the perks and to avoid jeopardizing that access. This can also stymie content pirates, who may still be able to break into content, but often find no market for it in a world where consumers have accepted the incentive-based legitimate systems and shun illegal markets for fear of losing their legitimate access.

This combination of law and social cooperation finally brought the American West under control, and turned a chaotic mob-rule countryside into a safe, orderly and profitable place to live. It may not be perfect—things still get stolen, and people still get hurt—but compared to its former state, it is a relative paradise of civilization today. And it is a shining example of what can be accomplished, given the desire of the majority to do so.

Big Brother, or Big Deal?

Of course, no one really likes security. Everyone wishes they could leave their front door unlocked at night, and not need to remember a password to get into their computer at work. Some cling to the notion that life is only worth living if it can be this way, and insist it is the only way of any future worth living.

Most of us, however, are more realistic than that. We understand why we lock our car doors, why we don't volunteer information to strangers over the phone, and why we don't open every e-mail we get. We understand why there are fences and drivers' licenses, metal detectors at airports, theft detectors at the department store and cameras in the ceiling at the grocery store. We understand that, as much as we might like it to be otherwise, there are needs for security and protection in the modern world. And we understand that security doesn't automatically equate to totalitarianism, as some fear mongers and Big Brother evangelists would like us to believe.

Some would like to think that a biometric system would somehow have to be tied in to a universal database in some government sub-basement, where all of a consumer's private data would be updated, and presumably accessed and abused, with every swipe of a finger. Not so: Existing fingerprint scanning devices would send the fingerprint data to the document itself, to be encrypted within and matched locally (within the machine) when opened… waiting for some universal database to clear and catalog every transaction would be too slow and impractical to be workable. A user's files and activities would not end up in a privately-controlled database somewhere, any more than a database buried somewhere is storing every instance of you unlocking your front door.

Others decry that no security system is perfect, and therefore they are by definition useless. Not so: Security systems are generally not expected to be "perfect," they are only expected to be effective at controlling loss; if the level of loss control is considered reasonable to the sellers, to the extent that fewer criminals are willing to go through the trouble of breaking the security for the resultant payout they expect, and the sellers do not lose more money than they want to due to theft, the security is considered successful.

Though we might prefer a world of free and unencrypted content, we tend to respond to access to good material, and the threat of losing access through inappropriate actions, by being good consumers, and accepting certain measures of security and control in order to gain access to that which is desired. Most businesses thrive on this theory, the idea that customers overwhelmingly prefer the easy option to get what they want, and if it is easier to just go with the flow, they will go with the flow. Easy access to desired content even trumps "Big Brother" concerns for most people, and the better the content, the less the concern.

The reality of the theory

To date, incentives have been applied to new technologies and selling paradigms, encouraging their use. The success of that use was dictated by a measure of the usefulness of the technology, against the undesirable qualities of the security system. If usefulness outweighed the undesirable qualities—as it did with cellphones and store cards—the technology was accepted. If undesirable qualities outweighed usefulness—Disney's "time-limited DVDs", for instance —they were abandoned in favor of better tech. Each successful application has ably demonstrated that we are capable of accepting some amount of inconvenience for the sake of effective security.

The realities of this instance is that it would take quite some time to roll out biometric ID hardware for all electronic devices, and this isn't even the greatest hurdle. An encryption "lock" must be devised to house the digital files, something that can be applied at point-of-sale or transfer, and unlocked by the consumer on-demand. A method of transferring the document's key access to another, at least on a limited basis, would be helpful (while not an absolute necessity, it is something consumers are used to, so it could be considered another "incentive"). Then consumers must be convinced to use biometrically-encrypted files through the use of incentives and disincentives, possibly including short-term extra incentives to get them on-board.

It is wholly possible that a combination of hardware, software and incentive/disincentive program could be rolled out and largely accepted by the public within a few short years… provided a dedicated organization was behind the push, and had full public support behind them. More likely, it would take between five and ten years for groups of organizations to work out standards, implement them, and find commercially-viable ways to get the public on-board… assuming the organizations all agreed on the need for the system, and got started on it together. A government could step in and create the standards for the organizations to follow… but waiting on a government to do that would probably take even longer than depending on the organizations to get it done. Consequently, we are probably talking about a system that could work today, but will probably not see widespread use for another decade or more. (At least that'll give the Big Brother alarmists time to get the howls of protest out of their systems.)

But that doesn't mean it isn't something to look forward to. Just like the American West was eventually brought under control through an application of laws and social cooperation, making it a better and safer place to live and do business, the digital landscape will be a better and safer place when document security has been established, and social cooperation backs the laws that protect it. And when that happens, there will be few people left who will look fondly back on the lawless era that preceded it.

When security measures are applied to a formerly unsecured product or service, no one is happy about it. But given time, everyone gets used to the situation, and even come to understand the advantages in better security. Digital document security can be established in this way, by creating a workable system and providing enough incentives for consumers to get on board. It's not impossible. And given the many examples of the past, and the fact that we will remain to be, for the foreseeable future, a goods and finance-based global market, I'd say it's inevitable.

Being NOML

Our planet has reached an era of crisis, a point at which civilization severely threatens the Earth's ability to maintain a biosphere conducive to human life. The early warning signs have been about for quite some time, but only recently have the signs been fully understood and appreciated… only now do the majority of people believe that the situation has graduated from "maybe" to "absolutely."

This has prompted leaders and individuals around the globe to espouse new lifestyles that will bring our planet back to a comfortable equilibrium for human habitation. Habits must change. New lessons must be learned, and old lessons must be un-learned (or, to put it in a generational perspective, your parents' lessons must be un-learned, and your great-grandparents' lessons must be re-learned). Our way of life is not sustainable… it's time to switch to one that works.

But this has led us to a second crisis, a crisis from within. As people are being told about the things they must do to improve the state of the globe—especially those who are most responsible for putting the globe in the state it's in—those same people are challenging each notion as a matter of course. Simply put, people really don't like being told what to do, and they especially don't like being told that they cannot do what they're already doing.

The situation is similar to that faced by people who want something, but who don't want the signs of that something to be apparent to them. As an example, American citizens demand electric power, and lobby for more plants to be built when power is scarce. But when officials decide to grant their request by building a plant, a curious thing happens: Anyone living within sight of the proposed location for such a plant does not want it there. "I don't want to see that nuclear plant in my view. Put it somewhere else. Anywhere where I don't have to see it… just not here." The phenomenon has spawned its own catchphrase, complete with a coy acronym: Not In My Back Yard, or NIMBY.

Today, the demands of altering the lifestyles of those who are comfortable in their present lives has spawned an effect that deserves its own catchphrase and accompanying acronym: NOML, or Not On My Life. This is actually shortened from Not On My Lifestyle, but in fact, either word applies. It is the effect of people who, upon being told that they must change their lifestyle for any reason, instantly rail against any change to their way of life, however large or small. "I want my life to stay the way it is… I want it to be normal."

This is not something to condemn people for. In fact, NOML is a natural psychological function. People seek stability… they get their lives working in a way that is familiar and reasonably satisfying, and thereby get used to it as it is. Psychologically, humans aren't great with change… at least, they are generally loathe to initiate change. Once change sets in, humans generally get used to the change, and it becomes their new "normal," their new lifestyle. But they are often dragged by their fingernails to get there.

We see this effect today in areas where people are asked to forego one luxury for a more sensible habit. A perfect example is the automobile. The car has been the changer of many a human habit since its invention… and to be sure, not all of them were welcomed at first, either. Traffic signals… speed limits… seat belt laws… all of these things were imposed upon people when they started driving, and make no mistake, each one was bitterly opposed by drivers as a threat to their personal "stability." But in time, each one was accepted by the majority, and eventually, became part of their "normal"… part of their lifestyle.

Today, people are being told they should leave the car at home, and take public transportation to work. The effect is predictable: Widespread resistance from car drivers who don't want to abandon their cars, their idea of "normal." The excuses are varied in subject, and degree of logic, but they all amount to: "I don't want to change my lifestyle." Is this unreasonable? As I said, it is psychologically ingrained to respond in this way. However, when contrasted by the people who already take public transportation—their "normal"—and who are perfectly comfortable doing so, it is plain that much of the protests are simple cases of fingernails being dragged on the ground.

The future for the car looks even more drastic. The automobile is overdue for a change in its basic power plant technology, to one that is less polluting. Unfortunately, a change in that power plant will probably result in needed changes in the way we use those cars, forcing us to reconsider how we apply personal vehicles to things like commuting, shopping and vacations. Habits that most of us learned from our parents will have to change, in some ways drastically, and it is not unreasonable to expect a lot more cracked and broken fingernails as they are dragged on the concrete of change.

Other examples of NOML can be found in the modern home, to varying degrees. Americans have demonstrated more resistance than perhaps anyone really expected when they were asked to replace their incandescent light bulbs with compact fluorescent light bulbs… after being told how much more efficient they were, you wouldn't think that the stores would be able to keep them in stock. Instead, the usual excuses of "I don't like it, 'cause it's different" cropped up, and the overall switch to CFLs has still not been fully accomplished in the U.S.. Other countries have seen the same effect, and are implementing (or considering) outright bans on incandescent bulbs, to speed up the transition.

But that was the easy transition, compared to the push to conserve more energy in the home. This push includes replacing appliances with new appliances that use less power, or that use zero power when turned off (many modern appliances use minute amounts of power even when turned off, resulting in what is known as "phantom loads"). It also includes things like turning off power strips when none of the things plugged into the strip are in use (again, to remove "phantom loads").

And many of us haven't seen other changes that will be even more difficult to deal with. In many places in America, water shortages have forced regulations on things like lawn watering. As our need to reduce carbon in the atmosphere grows, two popular American appliances are imminently at risk: The gas-powered lawn mower; and the charcoal grill. And as sprawl is seen to be increasingly bad for the environment, the lifestyle of the American suburb itself is threatened. None of these are things the American suburbanite will take lying down… they will fight tooth-and-nail before giving up their mowers, their grills, and their very homes.

Unfortunately—for all of us—many of these things must be curtailed or outright cut off, and soon, or we risk a global warming runaway effect that could render this planet about as hospitable as Venus. But we must do so over the psychological compulsions of NOML. Even those who are committed to doing better, often fall back on NOML in other aspects of their lives: "I'll change my light bulbs, I'll even turn off my computer, but I'm not going to stop driving my SUV." How are we to overcome NOML?

Historically, psychologically, there is one thing, and one thing only, that trumps the desire to avoid change: The threat to survival. When people believe that their lives are in danger, they are willing to risk change to survive. Therefore, appealing to people in terms of their likelihood of survival is perhaps the only way to convince them to act. If leaders want people to change, they must make them understand that their lives—not necessarily their mortal lives, but their comfortable lifestyles—literally hang in the balance. People must be made to understand how unpleasant their lifestyles will be, if they do not make the changes needed to mitigate that unpleasantness.

How do we do that? Here's a suggestion: In the 1980's, a television special called "The Day After Tomorrow" aired, depicting an America that experienced a limited nuclear attack. The program centered around a Midwestern city, and the individuals who had to suffer, survive, and in some cases die, following the aftermath of the bombs. It was honestly and accurately presented, nothing overly-dramatized, and its almost documentary realism hit a nerve in the American public. The program was so sobering that then-President Reagan, supported by that shell-shocked public, immediately took steps to limit nuclear arms in the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., to make sure such a thing never happened. Today, the possibility of an all-out nuclear exchange is severely lessened, and much of the world breathes easier.

Possibly a similar program is needed now… something that will accurately and realistically depict the lifestyles we will all be forced into if we refuse to take action against pollution and global warming today. Such a program, if properly done and if effective, could be enough to convince individuals and leaders to take the necessary steps to improve our shared global future.

Of course, there's no reason the program has to be limited to television. A concerted tie-in through the web would garner even more interest and attention, possibly creating a truly global event, with possibly global effect. Such an important global issue should take advantage of the latest in mediums to get its message across, and to make sure that message is spread far and wide.

And how likely are people to be swayed by a simple television program or website? Well, also in the eighties, NBC ran a special program called, appropriately enough, "Special Report." It was a fictional series of special reports that presented a terrorist incident in Charleston, South Carolina, wherein at the end of a program, a home-made nuclear device was set off by the terrorists, and a significant part of the southeastern coast had to be evacuated. Even though this program was advertised as fictional, featured major actors (including one who was the star of one of the highest-rated shows of the time on that same network, St. Elsewhere) and familiar character-actors, supposedly depicted the events of two days in a 2-hour time slot, and included disclaimers at the beginning and end of every single commercial break, it still managed to panic people nationwide, ala the War of the Worlds broadcast, who were duly convinced that the events had actually taken place. Put simply, the power of television is still as frightening as it has always been.

More recently, "webisodes" presented by "Lonelygirl15," a girl who appeared to be experiencing severe personal issues, and possibly in danger of her life, were seen by millions worldwide, and a great deal of consternation was experienced before the girl eventually revealed herself to be an actress following a script. Other entities have presented programs, webcast around the planet, that were as good in production as those made by major motion picture studios… or as real as material filmed in realtime by average people. The web has proven itself to be equal to television in its ability to grab people's attention, pull them into a program, convince them to accept its reality, and even to take action where they deemed it necessary.

And in no other arena may it be more necessary than in relation to our environmental crisis, a global issue that will have long-term consequences for the survivability of the organisms upon this planet.

Of course, there is another recourse that humans often take when faced with such a survivability dilemma: Many of them take the fatalist position, that is, "If it's going to kill me, let it kill me. If I die before it gets me, it's someone else's problem." Do Or Die—which certainly deserves its own acronym—becomes a defeatist proposition, and the change-averse decide they'd rather give up than fight. It's worth noting that the majority of these people really don't believe the threat will kill them, which explains their bravado… once they find themselves under the gun, most of them tend to take a different view. But until that point, they will steadfastly maintain their invulnerability, and embrace DOD as the natural response to NOML.

Unfortunately, once the gun is pointed, and the hammer is cocked, it will be too late to prevent its going off… and the gun is taking aim already. Is it already too late to scare these people straight… to fire off a warning shot that will spur them into believing the threat is immediate, and serious, enough for them to act? Even if we can overcome NOML, can we overcome the DOD fatalism that often accompanies it? Are we condemned due to the psychological inevitability of NOML, or is there a way to rally over NOML and DOD, and to get the needed job done?

Psychology is a powerful natural force… it is instinctual, and difficult to ignore. If it comes down to matters of psychology to decide whether or not we will save this planet, then Earth may already be doomed to suffer the worst effects of global warming, and we may be doomed to the inevitable struggle to survive through it. In fact, instinct could serve to prevent our survival altogether, like lemmings who plunge headlong over a cliff with their brethren.

Or, we could work hard on finding a way to beat instinct, to suppress the fatalism and fear of change, and to triumph over our natural limitations. If we, as a race, are as good as we say we are at overcoming our natural, animal limitations, perhaps we can yet stand proud and demonstrate that we're better than lemmings, that we can change the course of the world, and ourselves, for the better. As always, it is up to us to prove we are more than just naked Apes mired in the present, and reach for the future. We, and only we, can make sure NOML doesn't end up carved on our collective tombstones.

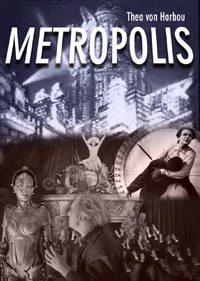

Metropolis: The one that started it all

A cover I created for an epub version of Metropolis that I created for myself.

City of light and spectacle… and of darkness and doom!

The first modern science fiction motion picture! One of the earliest mega-budget films! A marvel of cutting-edge special effects technology! An ageless parable that is as relevant today as it was in 1926!

A masterpiece that, like the Sphynx, exists only in its vandalized and incomplete form today!

This motion picture has an incredibly rich history in itself… yet, with its tortured past and highly-debated presentation, it remains as one of the most influential movies of all time. Certainly the format of science fiction films and novels owes much to this pioneer effort.

The Prototype

In 1924, when filmmaker Fritz Lang asked his wife, author Thea von Harbou, to write a story for him that would be the basis for his next film, science fiction films essentially did not exist. Other than shorts like Edison's Frankenstein and Melies' A Trip to the Moon, sci-fi concepts had not yet been rendered seriously on film.

However, the concepts inherent in Metropolis—the mega-city, the class struggle and inequalities between haves and have-nots, the demands of automation, and the threat of technology run amok—were already common and highly-debated themes in science fiction literature, and major concerns in a world entering the second century of the Industrial Revolution. Lang and von Harbou's message—"The mediator between the hands and the head must be the heart!"—is an almost over-simplified plea to emphasize humanity over industrialization, lest we allow industrialization to crush humanity utterly. Von Harbou delivered an epic script to Lang, and he set about the task of bringing her epic to the silver screen with gusto.

The Metropolis skyline: Massive buildings, painted backdrops and hand-animated miniature vehicles combined to bring us the ultra-modern city of the future, which would become a cinematic staple.

In its execution, Metropolis became the template for modern science fiction movies. Its heavy use of allegory and symbolic representation, remnants of the German expressionist movement in early filmmaking, became the standard visual tool of sci-fi. Its equally stylized representation of technology, guided by the necessarily visual demands of the silent era and symbolized by baroque machinery, flashing light shows, intricate controls and incomprehensible displays, became the artistic backdrop required of standard sci-fi. And its depiction of the city of the future, complete with monstrous buildings, hyper-modern fashions, flying craft, and endless highways clogged with futuristic vehicles, are among the universal elements of motion pictures.

Metropolis showed us the uber-horror of soulless technology run amok, destroying buildings and people, wrecking lives and societies. It presented the ideas that the demands of modern industrial civilization could ruin men, both physically and psychologically, if capitalism was allowed to rule over humanity—and that our machines could someday rise up and destroy us, if we were not careful and considerate about how they were used.

And let's not forget its robot: Futura (aka Parody), the beautifully-rendered art-deco woman-sculpture—worn by the same actress who portrayed the robot in human form—that inspired movie robots for the rest of the century… both the idea of human-styled robots, and of actors dressing up in robot suits to depict them. Though not the first robot in entertainment depiction (the stage creations of R.U.R. preceded it), it is undeniably the most elegant, certainly became the most famous, and was regularly used as the single image that represented the film on movie posters and art.

Metropolis pioneered the extensive use of special effects to make its city come to life. Visual processes were invented for the movie, such as glass-painting and split-screen photography, that are still in use today. The use of miniatures and realistically-painted cityscapes, stop-motion photography, and hand-animated scenes were also used liberally, requiring one of the largest budgets of any film of the day.

Metropolis' music was also on a grand scale, a full orchestral score complete with themes for individual characters, story arcs, action, and even parts of the city. The powerful, undeniably Germanic score served as the inspiration for the first sci-fi serials like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, who sometimes took their music directly from German operatic compositions. The tradition of the fully-orchestrated and commanding theme-based soundtrack is still popular today with sweeping sci-fi epics.

The Fall

For all of this, unfortunately, the audiences and critics did not "get" Metropolis when it was released… it was simply too unlike anything they had previously experienced. The resulting bad reviews and poor showings bankrupted Germany's UFA film studio, which had sunk a huge sum of money into the production, even while sharing the costs with an American film studio. After a pathetically short opening, the Americans took over distribution of the film, and decided to trim it extensively to emphasize the spectacle over the substance.

Rotwang and the robot: With a central character removed from the butchered script, the brilliant but tortured inventor becomes the prototypical Mad Scientist, and the robot's female appearance becomes confusing and pointless.

At the hands of people wholly unconcerned with the original plot or message of the movie, subsequent edits castrated the film, removing many scenes haphazardly, completely excising characters from the film—most notably Hel, the late wife of Joh Frederson, the master of the city; a central background character that fuelled the conflict between Frederson and Rotwang the inventor. They subsequently rewrote the caption cards in a sloppy and uncaring attempt to further simplify the script, until over half the film was gone and the story was a simplistic hash.

As the removal of Hel also removed the central motivation for the actions of Rotwang, leaving his actions and attitudes ambiguous at best, and unbalanced at worst, they ultimately resulted in another hackneyed sci-fi plot device: The wild-eyed Mad Scientist. Further edits were done by other studios and movie houses, to remove scenes deigned too racy or controversial for its audiences. After all this work, the movie became a disjointed mess, and audiences, if anything, got even less from it than from its original version. All that was left was a series of strange but pretty pictures, and a story that was juvenile and forgettable.

But before any more repair (or damage) could be done to the film, World War II struck a painful blow: Allied bombing leveled UFA Studios, destroying the original negatives of the movie. As most of the copies of the movie outside of Germany were the already-heavily-edited copies, the result was the effective loss of the film as a complete work.

Subsequent showings of Metropolis, throughout the decades, have been rebuilt from existing film stocks and occasionally-discovered negatives, none of which were complete, and many of which were in serious disrepair. Further, none of them presented the complete original story, and critics generally dismissed what was left of the movie as a beautiful work with a script of no value.

All that was left was its imagery, which served as the essential template for future sci-fi filmmakers to emulate, even to this day. Later sci-fi movies borrowed from Metropolis' imagery, and what of the original film was recalled by its contemporaries, in attempts to match or exceed its accomplishments. However, its surviving elements gave the impression of a genre that was immature, favoring style over substance, and struggling with concepts that were considered beyond its ability to effectively take on. The public's impression of sci-fi thus established, few sci-fi movies managed to reach beyond that image, and the genre struggled with that immature label for decades.

The Restoration

Fortunately, the original von Harbou novel survived intact, and by the sixties, was enjoying popularity as a re-released paperback book. The wealth of material in the novel, the many characters and complex themes, and the clearly coherent storyline, inspired buffs who realized how much of the original film work was clearly missing, and the poor remnants of the classic film were rediscovered by a new generation.

In the seventies, serious efforts were undertaken by multiple studios and film buffs to scour the globe, tracking down every surviving bit of film, and reassembling the movie to as complete its original state as possible. As the years progressed, and film versions or negatives were found with previously-missing scenes, new film edits were introduced to the public, and limited film restoration efforts began.

In the eighties, film producer Giorgio Moroder (Flashdance), a Metropolis fan, assembled the most complete version of the film at the time, and released it with colored frames and a modern rock soundtrack. Although he was lauded for his effort, the colored film and rock score did not win over many fans and was largely panned by critics. Moroder's film, as ambitious as it was, has since fallen into obscurity with the rest of the earlier restorations (though used VHS tapes and pirated digital versions of the movie can still be found).

As the years progressed, the original notes on the film were found or reconstructed from newfound sources. The original dialog cards were finally discovered, leading to a more accurate translation of the text to clarify major points of the script. Then the original film score was discovered, which also included notes on its timing with the script that further clarified many points of the story. It was performed by a modern orchestra, and added to the subsequent release.

In addition, computer-aided film reconstruction was reaching an incredible level of sophistication, allowing some scenes that were all but lost to age and deterioration to be recovered and cleaned up, and other badly-restored film to be rebuilt and clarified. The level of quality of many of those restored frames is nothing short of miraculous, a triumph of modern engineering and restoration art.

The Legacy

At the time of the 2002 release of Metropolis on video and DVD, restored by the F.W. Murnau Foundation, it was assumed that there were no other hidden caches of film or negatives remaining to be found, and that the latest edit of Metropolis would never be any more complete, nor would it look any better. The 2002 version had the original score restored to it, as well as clarifying text cards that were more faithful to the original work.

Then in 2008, a copy of what was purported to be the entire original film was discovered deep in the archives of the Museo Del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The film was immediately flown to Germany, where experts certified it as authentic. The newly-discovered copy clarified numerous plot-points, and fleshed-out the character of Slim (aka Schmael), Joh Frederson's lieutenant/spy. The badly-damaged film required extensive restoration, much like the efforts that were made on other filmstocks and negatives to produce the 2002 version. The 2010 version, billed as "The Complete Metropolis," is 145 minutes long, released in limited theatrical runs in 2010, and released on DVD and Blu-ray in November 2010.

Today, the 2010 restored version of the movie is considered "the best it will ever be." However, the "best it will ever be" milestone had been claimed before, and always, another bit of the original had been found and added to the sum of Metropolis' remains, like finding a bit of bone in a fossil that brings us closer to a complete skeleton.