Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 64

July 18, 2012

Redemption in The Incredibles

Well, here we are in another period of summer blockbuster superhero films to wade through. And as much as I enjoy them, I often find myself thinking about The Incredibles, Pixar’s animated superhero family. Since the movie was released, it has gone to my list of favorite movies and stayed there. I watch it frequently when I’m alone in the house and have a few hours to spare, securing myself in the basement with the lights low and the drinks and snacks ready and soaking it in like a guilty pleasure.

Well, here we are in another period of summer blockbuster superhero films to wade through. And as much as I enjoy them, I often find myself thinking about The Incredibles, Pixar’s animated superhero family. Since the movie was released, it has gone to my list of favorite movies and stayed there. I watch it frequently when I’m alone in the house and have a few hours to spare, securing myself in the basement with the lights low and the drinks and snacks ready and soaking it in like a guilty pleasure.

But is it just because I like superhero movies? Is it because of my fondness for animation? No, it’s much more than that. In fact, more than the live-action superhero movies, more than most adventure movies, The Incredibles deals with adult themes that I find I identify with… most notably in the character of Robert Parr, aka Mr. Incredible.

Robert, the central character of the story, undergoes an appropriately Herculean ordeal. At the beginning of the story, he is at the top of his game as the powerful superhero Mr. Incredible, successful, famous, and enjoying his life of helping grateful people everywhere. He’s even found love, and marries another superhero, someone with whom he can share the best aspects of his life. He’s happy and optimistic towards the future.

And then, in a New York minute, it’s all taken away from him by the vagaries of fate (not to mention a lawsuit-happy society and a chicken$#!t government decision). Suddenly, he can no longer perform the one service he was best at; even worse, he must hide the fact that he ever was a superhero for fear of public reprisal. Years later, he finds himself stuck (almost literally) in a menial job, personally stifling him and, through its greed-based atmosphere, ironically preventing him from actually helping people. It impacts his marriage and rots his spirit, leaving him feeling helpless and cast off.

It’s no wonder that, when he is offered a suspiciously-convenient chance to return to his superhero profession, he jumps at it, even though he has to lie to his family to hide the fact. Fortunately, the return to using his past profession also improves his home life, his health and his optimism. But it was all a setup, ultimately designed to literally kill him, at the hands of a man he’d once slighted years ago. Suddenly the game is serious, and this time his family is drawn into his danger; his dalliances have caused harm to his wife and kids, horrifying and humbling him immeasurably.

It is his family that ultimately frees him, and Robert finds that his family (and friends, in the guise of best friend Lucius, aka Frozone, and Edna Mode’s mad costuming skills) with their special strengths are indispensable in supporting him and helping him finish the job he started. And fortunately for Robert, the crisis they averted was serious enough to prompt the government to change their years-long prohibition against superheroing, allowing Robert, now with his family, to return to the profession he loves so much.

I find parts of Robert’s life echoing with mine: I am also familiar with abandoning past professions just as I thought I was to reach the top of my game, and wishing there was a way to return to that profession when I was stuck in a more menial position. I have also allowed my frustration to affect my family life in the past. Fortunately for me, I was able to overcome those feelings through learning to accept myself and my life, however imperfect, and move on; today, those particular demons don’t haunt me.

As a writer, I’ve recently had to accept the fact that my writing has not produced the sales and success I’d hoped for, forcing me to reconsider my situation and my desires. In a way, I’d felt stifled by my own decision to postpone further writing until I could figure out how to sell the books I already had (which, since I’m not a great salesman, could mean quite a hiatus). And to an extent, I blamed others for my situation, specifically, readers who weren’t buying the books (or who were downloading them without paying) and who weren’t helping me spread my name with widespread reviews and recommendations, plus an existing publishing industry that was doing all it could to discourage the growing crop of independent authors like myself that threatened to overturn their apple cart.

But like Robert, I had a family willing to help me over the obstacles of my own mind and actions, providing support and centering for whatever I needed to do. Through their support, I’ve managed to avoid getting lost fretting about the time spent not writing—and I know that they have my back, whether I continue to write, or pack it all in tomorrow and start selling hamburgers. My family is my rock, and with their help, I can do anything, or be happy with what little I can do.

In The Incredibles, Robert overcomes personal obstacles and past mistakes and, through the help of his family and friends, is ultimately redeemed. I’ve overcome similar personal obstacles and past mistakes, and through my family, have redeemed myself. And like Robert at the end of the movie, it appears my best years are now ahead of me again.

June 28, 2012

Does anybody care?

Since it’s fairly close to July fourth… and since I happen to be a fan of the movie “1776″… I feel it’s an appropriate time to borrow a question that was posed by John Adams in the dramatic finale of that movie, and which hangs somewhere in the mind of anyone who writes a novel, short story or article.

Since it’s fairly close to July fourth… and since I happen to be a fan of the movie “1776″… I feel it’s an appropriate time to borrow a question that was posed by John Adams in the dramatic finale of that movie, and which hangs somewhere in the mind of anyone who writes a novel, short story or article.

The question came up when I came across a blog post by Roz Morris, a response in letter form to a fellow writer who’d had a crisis of confidence in starting a book. In that post’s responses, I commented on something that I felt Roz had missed pointing out: That a writer should consider whether their desire to write is impacted by the possibility that no one will read their work (or, if put on sale, that no one will want to buy it); is it worth the effort if no one touches your work?

This resulted in a second posting by Roz, addressing exactly that question.

I was gratified to see a number of responses to the question at the end of Roz’ post. I continue to be slightly dismayed, however, by those who believe that there is something inherently wrong with writers who write primarily for monetary gain. Interestingly, my initial question of whether or not an author’s work was read in any form always ends up centering on the question of whether consumers should pay to read my books. The mere mention of payment for books seems to ignite instant controversy that burns past other issues and instantly polarizes writers and readers.

Although it is the desire of every writer, however unspoken, to have someone (and preferably a lot of someones) actually read and approve of their work, the idea of asking for financial compensation for same is often considered to be somehow contrary to the point of writing (and the desire for reading). This is often held up as an example of the difference between an artist and a craftsman—an artist creates because they must, a craftsman creates for money—and every writer would rather be considered, by themselves and by their readers, to be an artist as opposed to a craftsman.

Many writers like to say that they write because they “feel an urge” to do so, independent of any other need or compensation for the effort—they have a story that must come out. They also like to suggest (if they won’t say it directly) that they are producing for posterity, creating art for the world to enjoy. These are the words of artists, seeking a “higher plane” in which to enshrine their creations.

I wouldn’t say that there’s anything wrong with feeling that way; however, I am not so vain as to think the world needs my writing, no matter how important I, myself, might think it is. There are plenty of writers and plenty of stories… if they can’t enjoy mine, they can go read Dumas or Dickens, and it will matter little to posterity. In other words, I do not consider myself an artist; I am a craftsman, a skilled writer, one of many.

I am, however, vain enough to believe that, as a craftsman, I am a valid member of a society that is founded upon certain implicit and explicit agreements; and among those is the idea that I have a right to ask any compensation for my services that I’d like, and other members of society have the right to either pay my price for my services, or not pay my price and forego my services. This is the goal of any craftsman, a person who understands the worth of the skills they possess.

Are the needs of artists and craftsmen mutually exclusive? Let’s put it this way: Michelangelo didn’t paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling for nothing… nor is it worth any less because he accepted payment for it. It is possible to be an artist and still be paid; it is possible to be a highly skilled craftsman; and it is reasonable for art to have a price tag placed upon it.

There is no question that the state of publishing is in a severe state of flux, thanks to the digital market. The present reality of ebooks allows individuals who never had a realistic access to the commercial publishing system to create and sell or give away their writing, while the old commercial system struggles to maintain its relevance and dominance in the market. Prices are literally all over the place, and at this point it’s anybody’s guess where things will stabilize in the near or far future.

But there are still a few writers out there who honestly believe that their craftsmanship is worth financial compensation, and that other card-carrying members of society should not have a problem with the idea of paying to enjoy that craftsmanship. They believe that many people who consider themselves “artists” are merely those with not enough confidence to ask for due compensation for their efforts; so they give away what they should sell, and hope to somehow be compensated for it later. They understand that free doesn’t necessarily confer value. And they appreciate compensation as being (quite literally) worth more than accolades.

Now, all that said… let’s return to the original point, which was: Does it matter if no one reads your book? Is a writer satisfied that they have created a masterpiece, that all the effort was worth it, if no one ever reads it? And in today’s ebook-glutted world, it’s entirely possible that no one will ever read your book.

Is that okay by you?

Many authors would answer “yes” to that question: The work is worthwhile, even if no one touches it. Honestly? I don’t believe it. No matter how much they might protest, every author wants someone to read their work (and appreciate it). If they didn’t, they wouldn’t bother to save it; they’d just sigh, think to themselves “I did it, I’m done,” and hit the delete key. The very fact that they don’t immediately trash their work is an implicit indication that they do want someone else to see it. And I suspect that, if they did create such a personal masterpiece, and could get absolutely no one to look at it beyond the title, that it would drive them slightly mad.

I suspect those who do not go mad, avoid it by telling themselves their book will be discovered after they’ve died, and they will clearly hear the accolades from their purchase in Heaven (probably seated somewhere between Shakespeare and Hemingway and sharing the same bottle of port). Metaphysics aside, they are sure posterity will benefit from their munificence, even if they don’t specifically live to see it.

Other writers are more practical than that. And, like a craftsman who builds chairs, and suddenly looks around his shop to see a roomful of unsold chairs… some writers understand when it’s time to stop writing what no one is reading. No one needs a world full of unread books; in such a world, why spend time writing books no one will read?

In “1776,” John Adams despairs that no one cares about his efforts and sacrifices to create a new, independent nation, for them as well as himself. In the end, he has the commitment to keep going, making effort and sacrifices, sure that he would ultimately prevail and achieve his desired goal. One must wonder what he might have done if he continued to receive assurances that his goal of independence would never be ratified by Congress, and that the rest of the nation didn’t care about the outcome… if he’d been ostracized by his fellow politicians and condemned by the people, until he was completely alone in his efforts to free his nation. Would he have continued his efforts, if he was convinced that no one cared?

Of course, the desire to write a single book and have someone read it hardly compares to creating a new nation; and committing to writing a book that perhaps no one will read isn’t likely to result in your being hanged. All the same, a writer should realistically consider whether effort not appreciated equates to effort wasted… and given all the potential outlets of entertainment and information already available to the world, they should consider this question, not in terms of its impact on posterity, but of its impact on themselves.

June 24, 2012

Questions for the Cult of Prometheus

Prometheus, the sort-of Alien prequel, opened in theatres a few weeks ago, and already it’s generating a lot of buzz… not for its production or acting, which were nothing short of excellent… but for the many questions the movie raises about the origins and history of life on Earth, the spread of life in the cosmos, and the morality of experimentation with life. Many of these questions are left unanswered by the end of the movie, leading to the possibility that we could see these questions debated for years in the movie’s aftermath. (Caution: Major spoilers follow.)

Prometheus, the sort-of Alien prequel, opened in theatres a few weeks ago, and already it’s generating a lot of buzz… not for its production or acting, which were nothing short of excellent… but for the many questions the movie raises about the origins and history of life on Earth, the spread of life in the cosmos, and the morality of experimentation with life. Many of these questions are left unanswered by the end of the movie, leading to the possibility that we could see these questions debated for years in the movie’s aftermath. (Caution: Major spoilers follow.)

The movie begins with some pretty heady questions, right off: The audience is presented with a white-skinned humanoid (later on called The Engineers) being on an unnamed planet who stands by a waterfall and drinks a cup of something that moves. In seconds, his body is consumed, right down to the DNA, and he literally falls apart and falls into the water. And we are shown, on the molecular level, his DNA being rebuilt. Many things are unclear: Is the Engineer on Earth, or some other planet? Did he intend to essentially kill himself? There is no indication of surprise on his face, nor is there much of a sign of agony from being consumed. But his face is alien, so his lack of emotions that we would recognize is understandable. Finally, what is his DNA being rebuilt into? Another alien just like him? Or something completely new and different to whatever planet he is on? And if that unnamed planet is Earth… did this act somehow contribute to the development of life on this planet? In what way? (And we are given a hint later on in the movie.)

The movie then jumps to our future, where a group of scientists have arrived at a planet indicated by hieroglyphics found in multiple places on Earth, a star pattern that no human could have seen without the aid of modern telescopes. The hieroglyphs indicate giant beings pointing to the star patterns, which is naturally translated by our scientists as a suggestion to go there. So they went, bringing along a decidedly amoral (or maybe non-moral is a better term) robot, an executive of the corporation that financed the mission, and a video from the corporation’s CEO, now years-dead, advising them to follow the orders of the two scientists who convinced him to finance the mission.

It is mentioned here that Prometheus, coincidentally the name of the ship, was a god who wanted humans and the other gods to stand as equals, and so he was cast out of heaven. It is presumed by a clever audience that this little tidbit will somehow relate to the story about to unfold; and it does, but not in the way the audience might expect.

When the crew lands on the planet found closest to the star pattern, they naturally explore a nearby buried structure, and in moments the first sign of scientific stupidity is presented to us: The scientists decide the air is safe, and remove their helmets. What made them think the air was going to stay that way? That kind of lack of forethought doesn’t make for good scientists. We are also shown the presence of worms in the ground, so we know this area can support life.

Soon we are presented with hauntingly-familiar images to anyone who’s seen the original Alien. Rooms full of vases are very similar to the floor full of alien eggs encountered in the first movie… and as soon as people arrive, they begin to “sweat” and leak black fluid everywhere. Amazingly, crew members actually have to be advised to not touch things, and leave things alone; what kind of scientist has to be told not to contaminate a sample or corrupt a study site? Have “scientists” become complete morons in the future? Or maybe just the ones who work for money? Perhaps this tired trope serves us by forcing us to examine its clear foolishness, in order to reconsider the foolish things we often do in the name of science… or in complete ignorance of it.

Soon, a severed fossil of a head is found… but it turns out to be a fossil-looking helmet concealing the still-intact head of an Engineer. And the head is intact, not dessicated, despite the fact that the helmet was severed from the suit, not hermetically sealed, in an atmosphere that we have seen can support life, for a few thousand years. Could these beings be that resilient… even after death?

More importantly, the find allows Shaw to determine that their DNA and ours is the same, suggesting that we are products of the Engineers. Or maybe we and the Engineers are products of something else. Are the humans looking at their creators… or another creation? If another created the Engineers and us, that would make the Engineers our brothers. And if the Engineers are our brothers, could it be possible that they have similar questions of their creators?

We start to get interesting questions posited to us by the crewmembers now: The robot, David, asks Holloway why he was created, and when the answer is given—”because we could”—David asks how a human would feel if his Creator gave him that answer? And almost immediately, demonstrates his amoral nature by purposely slipping some of the bacteria from a vase into Hollaway’s drink. Did he do it because of Holloway’s answer to him… or did he already consider Holloway expendable, as David himself must have known he was considered?

And Holloway’s lover, Shaw, confronts the captain, who now confesses that the one thing he cares about is protecting mankind. He believes that the things they’ve found are a result of alien experimentation on an outpost planet, like a remote weapons testing installation, because they were too smart to carry on those experiments at home… and that they’ve clearly gone wrong. It sounds likely… but why? What is the purpose of hyper-accelerating DNA? Or is there a purpose at all? Was Holloway’s comment about the robot—”because we could”—a reflection of the humanoid’s feelings toward their experiments? Or was there an agenda?

Things naturally go downhill from there, in true horror-movie fashion: Two other crewmen who were stranded in the alien caves (when they got lost during evacuation, and no one noticed until the ship was sealed) come across snake-looking lifeforms with what seem to be suckers for heads. Again, the scientists demonstrate incredible amounts of stupidity by moving close to them, acting as if they’ve just found kittens in the grass… and are killed in minutes. These snake-like things showed up after the vases began leaking onto the ground, where we know there were worms; did the fluid from the vases cause the worms to mutate rapidly into something new? Or were these creatures in the fluid already, and grew on their own once released? And is this somehow connected to the rapid growth and development we’ve seen in previous Alien movies?

And soon, we find out that whatever Holloway ingested is killing him, and he begs to be killed before it gets out of hand. Somehow, though, he didn’t think tiny worms borrowing out of his eyes were important enough to mention to the woman he’d just slept with, Shaw. And when those who came in contact with him are examined for contamination, we discover that Shaw—who was supposedly sterile—is now pregnant and pretty far along, causing her to self-administer a caesarian section to get whatever it is out of her. What we see looks like a terrestrial squid, with the addition of one of those mouth-tubes that Alien made so famous.

Since we really don’t know what was in that fluid originally, we don’t know if it contained bacteria that eventually grew into this creature… or if it spurred the growth of something already inside Holloway and Shaw. And because it looks pretty much like a squid, it begs the question: Do humans have that potential creature hidden away in their DNA, or was it given to them? And, of course, it suggests that there is supposed to be a connection between the squids on our world and this alien; remember the humanoid at the beginning, who died at the waterfall as his DNA rewrote itself? Did that new DNA from the humanoid create the progenitors of squids?

David later stumbles upon a recording that convinces him the humanoids were going to bring these incredibly dangerous DNA accelerants to Earth; whereupon he returns to the ship and gathers his creator, the close-to-death Mr. Weyland, who secretly accompanied them in stasis hoping to find the fountain of youth (naturally). Not surprisingly at this point, they discover that one of the Engineers is alive in his own stasis chamber, and they wake him so David can ask the Engineer to help Weyland.

The Engineer proceeds to surprise everyone by going on a killing spree, wiping out all of the crewmembers present. Why would a member of a supposedly intelligent, superior race kill his visitors? Consider this: Could that Engineer have been left behind as a fail-safe for the experiment? Was he, in fact, a soldier tasked with protecting the installation, and therefore attacking the aliens (to him) who had shown up in his ship asking stupid questions? Or maybe, like another crewmember who’d been exposed to the snake-like worm and later went berserk, the Engineer was not in his right mind for similar reasons?

Something else to consider: If the Engineers were, like humans, created by another race… maybe they fear humans will turn out to be the superior beings in time, and are doing all of this to eradicate the competition. The captain’s suggestion that the planet is full of biological warfare materiel may be dead-on.

Finally, the Engineer climbs into the pilot’s chair and starts to take off… as David and Shaw believe, presumably to Earth. Do we have anything concrete to show he’s going to Earth? No; we do know that Earth has presumably been experimented on before. In fact, he could be going anywhere, including back to his homeworld to report the disaster; to some other world in order to carry on more experiments (or just dump the cargo on them); or even back to his homeworld to dump the experiments on them.

Or maybe, as David alluded to earlier on when he suggested that the goal of every child is to bury his parents… maybe the Engineers are planning all of this to attack their creators, not us. If he’s a good soldier, he may be trying to complete his mission… if he’s a scientist, he wants to complete his experiments (and yes, both of these options could lead to Earth)… if he’s a pilot, he may just want to get home and get paid… or punish those who left him in that situation. There is really no way to know for sure.

Either way, Shaw decides the Engineer must be stopped, and here’s where the Prometheus parable comes in: Shaw advises Prometheus to stop the Engineer ship, thereby preventing the Engineers from unleashing the monsters on Earth, which leaves humans able to someday attain a level even with the Engineers… to sit with the gods. In so doing, Prometheus is destroyed—thrown out of heaven.

Shaw seems to be stranded, but as it turns out, David was not destroyed by the Engineer, and entices Shaw to fetch him so they can fly another Engineer ship home. She agrees, but not to go to Earth: She wants to go to the Engineer’s planet. She wants the answers to what we want to know as well: Did the Engineers create man, and why? Were we no better than lab rats to them? Did they intend to eradicate us, or was the materiel found on the planet just intended to be another experiment to see what would happen? And as we hope she will find an answer, we too are hoping to see a sequel to this movie, so we might know the answers as well.

Most insidiously, looking back throughout the Alien franchise, and at Prometheus, we have to consider the inherent suggestion that the alien is, essentially, not a new species, but created by our bodies when exposed to this DNA-accelerating fluid or bacteria; the aliens are our progeny, our future, our children trying to bury us. We’ve been brought in a vicious circle.

Prometheus was an excellent science fiction production, though the story proved to be transparently manipulative in typical horror-fashion, much like the original Alien was. However, the real value of this movie comes from the moral, philosophical and metaphysical questions it poses to the audience, to consider our origins, our place in the world, our responsibility for our actions, and our consideration of other beings.

Best of all, it does not impose its own answers upon us, but leaves us to answer them for ourselves. Such debates could not only inspire further thought in our everyday lives, but it could spur a resurgence of interest in “intelligent” science fiction, stories and movies designed to make audiences think as much as (or more than) react to monsters, explosions and stupid scientists. This kind of movie inspires cult-like followings, those dedicated to unraveling its every secret (and positing a few of their own, just as I have above). Prometheus could be the jumping-off point for a new chapter of science fiction, a return to the overriding question of “Why?” that SF has let slide for far too long, and which it has always been at its best when trying to answer.

I’d say science fiction is long overdue for the influence of the cult of Prometheus.

June 20, 2012

The writer as carpenter

One thing writers love to discuss is the way in which they go about writing; almost, it seems, as much as the writing itself. They will debate and dissect various methods of story-building, preparation and production, reviews and rewrites, trying either to find the best method for themselves, or to convince others which is the best method for them.

One thing writers love to discuss is the way in which they go about writing; almost, it seems, as much as the writing itself. They will debate and dissect various methods of story-building, preparation and production, reviews and rewrites, trying either to find the best method for themselves, or to convince others which is the best method for them.

I am no different, and I’ve been asked frequently of late how my writing process works. I like to compare my writing process to that of a carpenter making a chair; an orderly process that invariably results in a recognizable product, as basic or ornate as I desire. Since I’ve used my writing process on over a dozen novels, and it has never given me a problem, I consider it a pretty good method, and I often recommend it to other authors. So, in the interest of edification of my fellow writers, I’ll describe the process here.

The first rule may actually seem strange, but bear with me: Most authors profess to first conceive of a story premise, a “What if?” question that will guide their writing project; Not me. Before I create a premise, I decide what kind of story I want to write… that is the actual beginning of any project. Compare this to a carpenter who decides to make a chair: First they must decide what kind of chair, as there are many kinds, desk chair, barstool, straight-backed chair, Chippendale, high-chair, etc, etc. Only when you know what kind of chair you intend to make can you actually get started.

For me, the questions are: In what genre or theme do I want to write? Do I want to write a cerebral or an action story? Serious or comedy? Is there a particular atmosphere or resolution that I want to achieve? For me, this is important, because I can’t do my best work on a book if I’m not “in the right zone,” that is, if I don’t feel like writing that particular type of story.

Once I’ve decided on the story type, I create my premise. Often, I have a few ideas lying around, in varying stages of development, that I can pick up at this point if they fit the type of story I want to write. If not, I can develop a new premise. The “What if?” method works for most initial story development, but sometimes it leads you in the wrong direction. Often, you are better off framing your premise in terms of a statement, rather than a question: “I want a story that results in this.” This leads you to develop a storytelling goal to aim for, and will subsequently guide your preparations to get there.

Imagine you are about to shoot an arrow with a bow. One method, “What if I shoot this arrow?” will cause you to lift the bow and let loose the arrow haphazardly, then see where the arrow falls. The other method, “I want the arrow to hit the bulls-eye,” requires advanced preparation, choosing the correct bow, sighting, aiming, and more carefully loosing the arrow at your target. The difference is that, where the former method may or may not hit something significant, reflecting on how significant your story may or may not be… the latter method is more likely to hit a significant point in the first place.

I prefer the latter method, just as a carpenter generally decides in advance how their chair is intended to look—say, a dining room armchair with a white fabric seat—before they start making it. Everything I do from that point on is intended to reach that specific goal, that product, that bulls-eye.

Once you have a premise, you have to world-build… the carpentry equivalent of collecting your woods, fabric and other materials. This is accomplished with notes, often lots of notes, about the settings, the types of characters involved, the atmosphere of your story, the bits and pieces of action you’d like to see happen. Don’t be afraid to go nuts here: The more notes you write, the more detail you can incorporate into your story, which should enhance its realism. If you’re writing about futurist fiction or fantasy, use this opportunity to work out your technological or mythological details. Also spend some time on the history of your world and characters, to give things a sense of perspective and direction… why they do the things they do.

Concurrent with your notes, begin to write up character synopses: Names; relationships; personality types; backgrounds; significance to story or other characters. Start out with your Primary characters first, giving them a good amount of detail and development, and add Secondary characters with lesser amounts of development and detail later (depending on the story, you may find you don’t need Secondary character detail at all—just names and basic traits).

As you fill in all of these notes and characters, always keep in mind the type of story you want to tell; this will inform what you add to your notes and characters so they can get you to that goal, just as a carpenter must select the proper pieces of wood, in the proper sizes, colors and grains, to fit their design. If your story will need an engineer that thinks fast on their feet in order to satisfy part of your story premise, this is the time to add those traits to a character. If a character is doomed to die in order to give another character something to react against and guide their subsequent behavior, pick them here. If the story requires specific aspects of a piece of equipment to be in place, such as a fast car or a computer that will malfunction, write the details down. Make sure it makes sense and doesn’t sound contrived… or if it is contrived, make sure you can give a substantial reason for your audience to accept the contrivance.

As your notes and characters start to gel, you’ll find yourself increasingly ready to write. For me, I hit a critical mass with all that information, and find it’s time to start putting a story together. Now comes the outline. The outline is where you’ll describe all of the main points of the story: What happens, moment by moment, in varying amounts of detail to make sure significant points from your notes and character details are hit upon. This is a detailed synopsis of the story, from start to finish.

Consider these your carpentry tools, what you’ll need to do a proper job. This step also suggests the sketches a carpenter might make of particular parts of a chair, or even the whole thing, to make sure he remembers all of the aspects he wants to be part of the finished product.

I write my outline as paragraphs of abbreviated sentences describing the action and the thoughts and reactions of characters, along with minor notes (in parentheses) to help make clear why an event is happening or why a character is reacting as they are… essentially, a synposis. I write virtually no dialogue here, unless a particular word or phrase is crucial to the scene. Usually, my paragraphs equate to a chapter in my book (and why that works out, I may never know), but there’s no hard and fast rule there; a chapter should end at an appropriate break-point in the story, or at a crescendo in the story that demands a break for emphasis. My paragraph endings usually provide that.

Do all of your story development here, referencing your notes and characters often. As you work on the outline, feel free to make changes to your notes and characters, especially as you hit points in your outline that need help moving to the next desired story point; it is easier to backtrack and rework snags in the outline than it will be in the final work. Write the story outline right up to the last scene—the bulls-eye you were always aiming to hit—and make sure there’s a bit of room for the epilogue at the end of the story, the triumphant bow, the prize, the result of hitting that bulls-eye.

Once done with the basic outline, walk away for a bit (maybe a day or two); then go back over it, line by line, to make sure it all makes sense with time and distance. Then take time to add embellishment to the outline, further fleshing out characters or adding detail to scenes, the things that will add realism to your work. Once you can’t think of much more to add to the outline, it is essentially done.

Now you’re ready to write, the equivalent of the actual woodworking. Armed with my outline, the writing of the story is fairly straightforward: I already have the gist of what I want to say, I just have to find the best way to actually say it. As I write, I add detail to a scene where the outline has left me some leeway, and I write the dialogue as I go, allowing the notes and outline to keep the dialogue moving in the desired direction. (I will occasionally “allow” my creations to go off on a non-sequitor, but only when I can easily guide them back to my intended course.)

At this point my work comes to me as easily as a carpenter cutting wood, shaping the legs, and carving interesting patterns and rosettes into the frame. The writing generally goes without a hitch, following my outline and notes closely and applying artistic license to the open areas. I will occasionally come to a pause on a difficult passage, similar to the pause a carpenter must make if he comes to an unexpectedly rough or misshaped section of wood; careful not to ruin the overall product, the difficulty must be considered and carefully worked to get it into shape. If you did a good job with your outline, notes and characters, there should be few pauses of this kind to slow you down.

If all goes well, I finish the story just as a carpenter finishes the body of the chair: I call it a draft, but in actuality, I won’t be using it as a guide to rewrite the final; the outline was the real “draft,” and this, with some (hopefully) light editing and proofing, will be my final manuscript. At this point, I usually take a break from the book, then come back after a few days to a week to read it and proof what I’ve read. Again, if you did a good job with your characters, notes and outlines, the story itself should present few areas to fix or rewrite; maybe an edit to a section of dialogue to clarify a point, or a better description of a moment to improve its pacing or emphasis, etc. Most of the work will be proofing actual words, grammar and spelling.

This is the polishing of the product, making sure every angle looks good. As with carpentry, it’s possible to go too far with polishing, not being able to tell when the product needs no more work; and if you’re not careful, you can over-polish and take the life out of a section; but as you write more and more, it will become easier to recognize the point at which you can stop messing with it. When you’re done, you should have exactly what you envisioned at the beginning of the project, the product that you intended to make (and presumably sell). And if it sells well, you will know that you also have all the tools you need to make more, either just like it (creating sets, the sequels some readers love so much) or completely original.

And there you have it: The carpenter’s model of producing books, as applied by me. This model may not work for everyone—especially those who like to just take a hammer and chisel at a piece of wood, and see what they get at the end of the day—but for those of us who are trained to be more “workmanlike” at the tasks we take on, this model is a good one, and has not failed me yet. Again, I recommend the method to any author looking for a good writing process, even if you only need a few parts of this process to add to your own. If you use it, good luck… and if it works, I’d love to hear from you how well it worked for you.

June 10, 2012

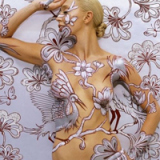

Sex in books: Give ‘em what they want

When I was a boy, I would often pick up novels wherein I didn’t actually read characters’ swear words; instead, I read the author’s account of the characters’ swearing, to wit: “He swore,” “he gave his opinion in language not fit for polite society,” “her language, as crude as any sailor’s, caused her companions to blush furiously,” etc. And I was introduced to the familiar scene known as “kiss kiss, cut to morning,” in which something significant happened in-between, but was apparently not appropriate enough for me to be privy to.

When I was a boy, I would often pick up novels wherein I didn’t actually read characters’ swear words; instead, I read the author’s account of the characters’ swearing, to wit: “He swore,” “he gave his opinion in language not fit for polite society,” “her language, as crude as any sailor’s, caused her companions to blush furiously,” etc. And I was introduced to the familiar scene known as “kiss kiss, cut to morning,” in which something significant happened in-between, but was apparently not appropriate enough for me to be privy to.

The United States has been called a very Puritanical country for most of its existence; it stood for very pure concepts like hard work, clean living, ten commandments, church on Sunday, that kind of thing. And these concepts were (mostly) reflected in its media, stories that generally depicted what the people in power wanted everyone else to think was The American Way. But as some people wanted to tell stories that weren’t necessarily emblematic of The American Way, the U.S. applied censorship to many mediums, rewriting or removing the parts that upset their sensibilities.

This was the standard in American literature, as well as television and movies, throughout the twentieth century. Certainly there were exceptions to this rule, but such exceptions were quickly seized by the censors and given “X” ratings, hidden behind curtained walls or cardboard backings, and protected by gatekeepers that demanded to see your ID in order to judge you worthy to see the forbidden things.

Welcome to the twenty-first century, where we have seen many changes in media related to the depiction of sexuality and impolite language: Where, in the past, all of that was hidden away, today the exposure to such risque fare on pay-television has slowly brought about a lowering of the gates, as it were; cursing pierced the boundaries of pay-cable and ended up on basic cable; lingerie eventually begat bare bottoms on prime-time shows; and finally, sex scenes that showed everything except the holy grail, clitoral penetration, appeared before the witching hour of midnight. As much as three hours before midnight, in fact.

This sea-change has come about in books as well, including areas previously considered to be pre-adult fare, like science fiction and fantasy. My first exposure to this sea-change came from the Wild Cards series edited by George R. R. Martin, a science fiction series in which I discovered very explicitly-described sexual situations, including (but not excluded to) a pimp who required a blow-job from one of his ladies in order to wield tantric magic.

Whoa.

I’ve followed these changes as a reader (avidly!), and as an author trying to create stories for other readers to enjoy. As I’ve developed, and developed my stories, I’ve come to appreciate that the audience is much more tolerant of the more personal moments of human interaction, and do not shy away from things like sex and crude language. Moreover, as an independent author I do not need to respond to the concerns of publishers who were more concerned about their reputations, or the reputations of those who supported them, and who edited books into G-rated products accordingly.

And finally, a wonderful aspect of ebooks is that a consumer can read one without displaying a cover that might tell others what they’re reading. Consumers have discovered the liberating aspect of being able to read any ebook without worrying about public reaction or condemnation, whether the book be Starship Troopers, Lady Chatterly or Harry Potter.

In short, I can be as lewd and crude a writer as I need to be, in order to tell a good story and entertain. And readers can happily lap it up without reservation.

I applied this realization to my earlier books when I updated them, as well as applying it to my more recent books as I wrote them. So far, I’ve heard a few comments from people who thought the more explicit sex scenes were not needed for the story, but they have been more than compensated for by those who have told me they enjoyed the books more for being unafraid to show relationships up-close and personal.

It appears that sex really does sell; and I won’t shy away from writing it where it’s appropriate to the story. (And maybe, occasionally, even when it’s not.)

June 8, 2012

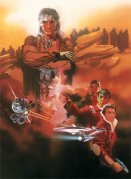

The Wrath of Khan sucked. Yes. It did.

This week, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan turned 30 years old (Oh! My back!), which is naturally resulting in people all over talking about how this movie was the greatest of the Star Trek franchise, bar none.

This week, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan turned 30 years old (Oh! My back!), which is naturally resulting in people all over talking about how this movie was the greatest of the Star Trek franchise, bar none.

I say: Horta-marbles.

So, I’ve waited thirty years; now, I’m going to tell you why The Wrath of Khan was a lousy movie, a lousy Star Trek movie and a lousy science fiction movie.

We know that Wrath was developed from the original series episode Space Seed, in which Khan and his followers, products of the Eugenics Wars, were discovered in a sleeper ship hundreds of years after they (take note) lost their war. These so-called physical and intellectual supermen tried to take over the Enterprise, but (again) lost, and were banished by Captain Kirk to a small uninhabited planet “to rule.”

Which should tell you right off that these guys weren’t the great s#!+s they thought they were.

Fast-forward about 25 years, to a movie that depicts an Enterprise being used as a training vessel (yeah… for the most celebrated ship in the fleet, that makes sense), and a survey vessel from that same Federation that is apparently not smart enough to notice that the solar system they’ve entered, which has been mapped by Federation ships before (including the Enterprise) is missing a planet. In fact, another planet has supposedly been moved out of its original orbit (something else the crew of the Reliant should have noticed), but instead of changing the temperature severely, the planet gets stoopid dust storms. Naturally, they find the surviving members of Khan’s group, but can’t say the words “Beam us out!” fast enough to avoid being captured.

A great deal of my angst over this movie is in its bad story and editing, leaving characters hollow and pointless: Saavik, for instance, has her part Romulan heritage left on the cutting room floor; characters like Scotty’s nephew become nameless footnotes, lessening the impact of their later death scenes; Chekov and Terrell can’t just beam out of Khan’s world before Khan’s guys can cross a few dozen yards of sand to catch them; Khan “remembers” Chekov, despite the fact that they never met in the original story; Khan, the “superior intellect,” apparently responded to the loss of his wife and the change in his planet by going insane, but none of his superior followers has the stones to explain his obsession to him or take steps to prevent their all being destroyed by the man; Khan’s son is the only one of the baddies group, other than Khan, who utters a word through the entire movie (besides “Aaugh!” when their ship is attacked); we discover Kirk fathered a son and never met him or kept in touch with his mother… and we’re supposed to actually care; how one of the worms Khan dropped in Chekov’s ear could have been dropped into the ear of just one of the scientists in order to find the genesis device, preventing the need to torture the rest of them; Khan’s followers are mute slabs of meat, and in the end, we feel nothing about their being blown up; and let’s face it, the whole Moby Dick theme (with lines from Melville’s book altered to use celestial references that Khan couldn’t possibly know) is lame, even when it’s presented by Ricardo Montalban, the one man in the universe who seems to be able to out-overact William Shatner.

So, we come to the part that everyone says is the best part of the movie: The starship fights. Okay, considering this is the first time in the history of the franchise that we see the Enterprise (and the Reliant) taking serious modern-special-effects battle damage, the battles were notable and memorable. Beyond that… meh. We see two starships close enough to spit at each other, which still miss each other with regularity. We get the whole “Khan displays two-dimensional thinking” bit, and we’re supposed to buy the premise that a “superior intellect” man who could rule a world (albeit temporarily), steal away on a sleeper ship, steal a starship, who has presumably thought about attacking and killing Kirk for many moons, and who’s probably heard of submarines, has never figured out three-dimensional space warfare. We see the old TV-series holdover of having bridge equipment blow up when a piece of ship dozens of decks away gets hit with a phaser blast… so you know they’re connected.

And finally, we have the Tech-Of-The-Day, a device the size of a man that can change the life-potential of entire planets; and the stereotypical “countdown to disaster” when the genesis device is started—but they never just go off, do they? No, we have to suffer a countdown for it to happen; but the Enterprise is crippled… oh no! Will they die? No, because Spock manages to get the engines fixed mere seconds before it’s too late. Whew. And oh, yeah, Spock is now going to die of radiation poisoning. On a ship that runs on antimatter, in which everyone in engineering is dressed like the Michelin Man to protect them from something, but no one goes where Spock dares to tread, and after we’ve seen radiation sicknesses cured with hyposprays in episodes of the original series…

You see where this is going, I’m sure. Khan isn’t consistent to Star Trek, not the original series nor the particular episode in which it was birthed. It’s not consistent with science fiction, not even the Trek brand of sci-fi. And on top of that, it’s just not well put-together. Everything in this movie just comes off as being contrived in order to push some incredibly obvious emotional buttons, while ignoring how much (or little) sense they make. It’s showy, it’s pretty, it has more colorful Star Fleet uniforms… and it’s stupid. It’s about as realistic as The Blues Brothers, complete with stupid Nazis.

And this is the movie that fans declare is the best Trek film ever.

IqnaH QaD. (Go look it up.)

It’s funny how Trek fans, who like to proclaim the intellectual superiority of their program of choice, are amazingly unsophisticated when it comes to their preferred Trek movies. The even-numbered movies that most cite as “the best” are in fact the worst when it comes to science fiction realism, Trek continuity and downright story quality. And Khan leads the pack of guilty movies (okay, it’s second, right after The Voyage Home, and barely preceding the disaster right after that, The Final Frontier… but it has the virtue of being iconic of all of them).

The Wrath of Khan was a redshirts movie: Let’s do stupid stuff and beat up on each other, yargh! It was designed to impress Star Wars fans, who (let’s face it) weren’t nearly that concerned with trifles like science and storylines. It was fluff… pure, unadulterated fluff.

You want good Trek movies? Star Trek: Generations is probably the best, in my opinion; followed by Star Trek: Insurrection. These movies had action, but they also had stories consistent with Trek continuity and the pseudo-science fiction universe that Trek was based within, paid close attention to the established behavior of Trek characters and didn’t go in any phenomenally stupid plot directions. Were they perfect? No; but let’s face it, Star Trek has never been a “perfect” show. But Star Trek has (almost) always had a way to look at the future that was thoughtful, humble and optimistic, and both Generations and Insurrection embodied that attitude.

So, I’ve said my piece, and you can now judge me according to my opinions of Star Trek movies.

Next week, I’ll discuss Lost In Space.

June 7, 2012

The secrets of indie success: There is no spoon.

L.A. is a great big freeway.

Put a hundred down and buy a car.

In a week, maybe two, they’ll make you a star.

Weeks turn into years. How quick they pass.

And all the stars that never were

are parking cars and pumping gas.

A thread on the MobileRead site has spent three months and sixteen pages exploring The Secrets of Indie Success… only to find out that there really aren’t any.

The above lyrics, from the Dionne Warwick hit Do You Know The Way to San Jose? are very apropos to the state of the independent writer’s world today: The lure of easy writing tools (the computer), the relative ease of producing ebooks, and the universal access to the internet and social media, lead people to think they will be able to write a book and become rich, almost overnight. The reality is that, despite what everyone would have you believe (and most of them already made it big or heard it from someone who made it big, which is how you heard it), it’s not that easy, and you’re as likely to get nothing for years of work besides a tedious existence and an occasional thought to what went wrong.

Sixteen pages into the thread, author David W. Fleming states: “My faith in the ‘wait to be discovered method’ diminishes each day.” And well it should: In a world of 7 billion and climbing, “waiting to be discovered” is a fool’s game. Sure, it’ll happen to about .0000001% of the population… how are those odds for you?

I think only one useful thing has come out of that thread: The fact that “waiting to be discovered” is not the same as “getting noticed.” And “getting noticed” is about doing the things that no one else is doing… yet. Being the leader… not another rider on the bandwagon.

Authors who go through traditional publishers are essentially paying the publishers to get noticed in traditional areas… best-seller lists… media promotion… spots on Leno and CNN… etc (as long as they still work). Independent authors, hoping to bypass the traditional route, try to accomplish the same thing through the web and social media tools. And the web and social media have the unique position of being a place where you can say what you want, including trying to sell something… and a place where users hate to be bombarded with commercials.

Social media is great, but it’s pretty much all bandwagon. By the time it gets popular, it’s already used up by the first-responders. Everyone else is by definition an also-ran, and the public is already tired of hearing from promoters like you. It can be used to connect to you… but people have to know you first to want to connect to you. You won’t get that through social media, no matter how much you hang about and post (it’s probably significant that social media, when abbreviated, becomes SM).

Getting noticed in non-traditional areas… social media, etc… requires more than just Being There. You have to find a way to Stand Out, to be significant, to be an icon.

Amanda Hocking (and I know, I hate that I’m using this example too… but truth is truth, baby) didn’t sit back and wait to be discovered. She aggressively marketed herself with her book, while standing on the crest of the wave of popularity being enjoyed by her subject. She scored interviews, and knew how to cross-link those interviews to sites full of people interested in her subject, her product, and later, herself. And as her popularity grew, she parlayed that into more interviews, more popularity, and finally the notice of a publisher, who took over all of those tasks for her so she could just write. Today, Amanda is not soaking up the web and social media as she once did… but she’s appearing in the traditional popularity venues, the published best-seller lists, the TV appearances, the bookstore posters and end-caps.

Being savvy… being aggressive… being bleeding edge. That’s what works. As it always has.

In The Matrix, Neo was told by a young disciple of the Oracle that the secret to bending a spoon with your mind was understanding that “there is no spoon.” It is this out-of-box thinking that is required of any independent author to penetrate the traditional layers of advertising and promotion and Get Noticed today. Look at how well it worked for Neo.

Unfortunately, writing being a traditional field tends to discourage non-traditional thinking… and many of us independent authors like to think: “I’m selling ebooks; isn’t that non-traditional enough?” Well, it was in 2005… but now, not anymore. What else you got?

That’s our task as independent writers: Figuring out What Else We Have that is significant, that is icon-worthy, that will get us a shot at Leno and CNN… and that we can get out there for people to see. Or get yourself a publisher, and let them do the job for you. Because if you can’t do that, and are just “waiting to be discovered”… well, odds are you’ll be waiting a good, long time.

May 29, 2012

Inertia: Enemy of progress

I was recently reminded about an experience I had as a teen: I went to an Earth Day show at the Mall in Washington, D.C. and, among many things I saw, I had a chance to examine no less than four fully electric automobiles, all endorsed by the U.S. Department of Energy, a few made by major auto manufacturers (GM was among them), and at least one of them expected to go to market within 5 years.

This was 1978 or so.

And I remember thinking how great that was, because it meant that by the year 2000—because, in 1978, 22 years into the future sounded serious enough to warrant the phrase “in the year 2000″—there would be multitudes of electric cars to choose from, and the country would be driving primarily electric vehicles by then.

Obviously, that didn’t happen. And when you ask someone about why it didn’t, the answer is likely to involve some form of inertia.

The best definition of Inertia is the resistance of any physical object to a change in its state of motion or rest. This is a definition that applies to physical bodies and applications of classic physics; if it is moving, it wants to keep moving, if it is at rest, it wants to stay still, and additional physical effort must be applied to change that.

A favorite joke of mine—and one which happens to feature inertia—is the one in which a man slips and falls from a 100-story building. At the 20th floor, a man sticks his head out of a window and shouts at the falling man, “How are you doing?”

The falling man shouts back: “So far, so good!”

Though inertia as stated is intended to apply to physical bodies, it has also come to be applied to concepts like institutions and individual thoughts; inertia is that which prevents institutions from changing internal practices, and which prevents individuals from changing personal habits. It also affects concepts like The Future, to wit: Inertia is that which prevents the future from happening.

Take the example of electric cars: Although we had the germs of electric autos and battery technology in 1978, we largely didn’t follow through on developing them; the oil-based automobile had taken over the planet, rich industrialists had committed their lives and fortunes to the oil-based auto, and were less concerned about the environmental improvement of the planet than they were of seeing their bank accounts shrink. Those industrialists took concrete steps to slow the progress of electric autos, to bring battery research and development to a crawl, to influence environmental regulation in favor of easing pollution laws and controls, and to market cheaper and even more polluting vehicles by appealing to the public’s desire for luxury over environmental concerns.

Their efforts to keep the oil-based auto plugging along amounts to inertia.

Here’s another example, involving the electricity in your home. For years, Americans used standardized incandescent light bulbs to light their homes. Recently, it has been revealed that the incandescents are very inefficient, costing Americans millions of dollars in lost and wasted heat; so, in order to make American homes more efficient, lights of differing technologies are being developed, using fluorescent technology, halogen, LED and other technologies.

However, all of these technologies must deal with the standardized screw-in bulb receptacle that has been built into every lamp and light fixture for the past century. And many Americans have voiced a preference for the older bulbs, not because they are all that great, but because they already fit into their existing lamps and fixtures, and don’t require them to learn anything new in order to light their homes. This is inertia at work.

Let’s go back to the car. A number of years ago, anti-lock brakes were developed for autos: The computer-assisted brake systems proved very quickly to be able to stop a car in a shorter distance by avoiding the wheel-lock and skidding that extend braking distance. The technology proved to be better at “pulsing” brakes than just about any human, thanks to its millisecond response times (not to mention lack of mental distractions to impact its performance).

Today, you would think anti-lock brakes would be on every car brought to American shores, given its proven ability to stop cars sooner and safer. But it is not on every car, and is not even an option on many cars, because American drivers cling to the belief that they can stop their car as soon as a computer can (or that there’s not enough of a difference to merit spending the extra money for the option). This has kept anti-lock brakes from becoming standard issue on all American cars… inertia at work.

Today, we are regularly introduced to technologies that can improve our world at the personal, local, regional and global level. Yet, people resist those technologies, either because they will force us to adopt new habits or adjust our existing technology to suit; or because we are more concerned with our present comfort than making an effort to ensure a better future; or simply because we just don’t believe the new technology can do the job better than we can or better than the old technology could. Many life-saving, energy-saving or just effort-saving technologies are constantly held up by needless inertia, a resistance to allowing that technology to assert itself, to progress, to take off.

As you may have guessed by now, I’ve been thinking about this in relation to automobiles lately. As I speak, there are test automobiles using the latest computers, GPS systems and maps, radar and imaging systems, taking the first steps towards fully automating the process of driving the car. I see this as a necessary next step in automobile evolution, taking the dangerous job of piloting the car out of the hands of flawed, careless, easily-distracted human beings.

As people continue to try to squeeze more everything into their time, they find themselves with less attention to give to driving duties. Considering that the automobile is the single largest cause of death in the U.S., and that less devotion to driving clearly leads to more accidents and death, this clearly can’t stand. But instead of the increasing laws designed to safeguard us by preventing us from doing more and more when behind the wheel, we could instead allow everything save one activity—driving itself—and accomplish the same goal.

Self-driving cars aren’t quite ready for prime time yet, but when they are, we can expect most drivers to show heavy resistance to them, for just about all of the reasons listed above: People will not want to give up the activity of driving that they are used to; they won’t trust the cars’ computers to do a better job at driving than they can do themselves; and they won’t believe self-driving cars will make for a safer future on our roads. In short, many people will fight tooth-and-nail to resist the self-driving car. And as it was with electric cars, resistance could delay their development and adoption for decades.

But eventually, the benefits of self-driving cars will become numerous and more desirable, and more people will adopt self-driving cars. And when they do, we will see an example of how inertia can speed change as well as slow it: As more support goes to a new technology, it speeds up in developing new advances, and the public shows more willingness in adopting the changes; it changes from rest to motion, and inertia helps to keep the motion going.

This discussion of inertia does not only apply to autos, of course. It can be evaluated against alternative energies, the internet and social media, cell phones and personal technology, eating habits, popular shows and media, and pretty much anything that undergoes change over time. As in physics, inertia is a universal force; we cannot ignore it, and we must always consider its force upon us as we try to move into the future.

But we must also consider inertia’s ability to keep us heading down the wrong path. Just as the man falling from the building will eventually discover, unchecked inertia can lead to disaster.

May 15, 2012

The success of series

As I write this, The Avengers is well on its way to becoming another record-breaking movie. As well, we have seen three Twilight movies, four Pirates of the Carribean movies, six Star Wars movies, umpteen Harry Potter movies, sequels to The Hunger Games and Iron Man are in the works… you know what? I could blow three or four paragraphs on all the sequels and series of movies out there.

As I write this, The Avengers is well on its way to becoming another record-breaking movie. As well, we have seen three Twilight movies, four Pirates of the Carribean movies, six Star Wars movies, umpteen Harry Potter movies, sequels to The Hunger Games and Iron Man are in the works… you know what? I could blow three or four paragraphs on all the sequels and series of movies out there.

Suffice to say, continuations are popular in movies. And why not? A movie can only pack in so much information… a typical 2-hour movie is perhaps the equivalent of a 100-page book, and these days, books pack in 3-400 pages. Multiple movies are a great way to get in all of the book’s content (well, more of it, anyway) and provide more well-rounded entertainment to the moviegoer.

Series like Twilight are good examples of the now-familiar extended movie, each movie following the same characters and picking up where the previous movie left off. And The Avengers has, in fact, pioneered no less than a new form of movie series: A group of individual movies which stand up separately, but which also culminate in a movie that encompasses all of the previous movies and creates a greater whole. To be fair, the idea is now new, being something that the comics industry has taken advantage of for decades; but it is new to moviegoers, and it turned out to be very successful (due in no small part to the quality of each individual movie, helping to whet the audience’s appetite for the next installment).

Books, of course, have taken advantage of series mania for decades: Series stories are in big demand, and those who sell (and buy) books are clamoring for more series to keep drawing in the public. The power of movie series hasn’t been lost on marketers either, who understand the value of cross-promotion, as well as the power of a successful product to attract consumers to the next product in line.

To me, the greatest draw of a series is this: The more material that is created relative to a series, the more fleshed-out your characters and your setting become. The incredible world of Star Trek is a perfect example of this: Between the television shows, books, comics and movies, you have a universe and established characters that seem almost as fully-formed as real life. It’s no wonder that attending a Trek convention is almost like being in a family reunion for many visitors. The various movies that culminate in The Avengers accomplished the same thing, providing a complete background for each major character that allowed the final movie to avoid all that character exposition and cover much more storytelling ground.

Though some complain about the sudden predominance of series, their success in the marketplace is undeniable. There’s something to be said for familiarity of characters and storyline, the idea that you already know what you’ll be getting when you plunk down your money. Maybe this is a sign that the public is becoming increasingly wary of the unknown; but more likely, it merely demonstrates a willingness to repeat an enjoyable past experience.

And there’s a powerful draw to the shared experience. Complete strangers can bond over characters that they all know like the backs of their hands, discuss their adventures, commiserate over their trials and gossip over their personal lives. The popularity of series brings disparate people together, giving them a common ground for communication that can branch into other areas later. It makes social contact and bonding easier.

Unfortunately, this may be the motion picture theatres’ last hurrah; convincing people to come out and spend over $20 per couple to see a movie is becoming increasingly difficult, especially as they can wait a few months and watch the same movie from the comfort of their home for significantly less. The social power of series movies is strong, and it is surely helping to bring groups together for the shared pleasure of seeing their familiar friends on the big screen when they first come out. But, as most pundits predict, the life-span of the neighborhood movie theatre is drawing to a close.

When theatres finally do become few and far between, will the popularity of series, having served their purpose for the movie industry, finally wane? No; their purpose is still well-served in other media, including the growing amount of media we’ll be watching at home and online. Hopefully, even if we are all watching movies separately, the popularity of series will still draw us back out of our homes to share our experiences and maintain our common interests.

May 9, 2012

Should we hide the “science fiction” label?

Science fiction, as a genre, has always had a “no respect” aspect to it… well, maybe not forever, but certainly all the way back to the early 20th century, when it was popularly used to entertain youngsters and fill low-budget preview space before movies.

Science fiction, as a genre, has always had a “no respect” aspect to it… well, maybe not forever, but certainly all the way back to the early 20th century, when it was popularly used to entertain youngsters and fill low-budget preview space before movies.

It’s an odd realization, considering the fact that science fiction has also been a noticeable part of a number of entertainment genres, and has not always been considered an element undeserving of respect or denigrating to the story. Take The Boys From Brazil, for instance: A thrilling drama that would not exist if not for its SF elements, but which is still considered an excellent story.

The trouble with the SF label may be the fact that it is too broad, encompassing everything from aliens, faster-than-light travel and parallel dimensions to the latest gadget-pen in James Bond’s pocket. As a result, it has been used as the primary identifier for a number of stories that could have been identified more accurately by labels such as thriller, drama, comedy, mystery… and possibly causing the same confusion that would result if you’d taken stories from each of those genres and labeled them “Western” because someone in the story had worn blue jeans.

This confusion has resulted in some books, motion pictures and television shows avoiding the use of the science fiction label. There is anecdotal evidence, at least, that using the science fiction label on media has resulted in significant parts of the public reactively avoiding the media without further investigation. In the same way that much of the public seems to have a dislike of (or outright hostility to) most or all science, they have extended that dislike to science fiction, and shun it out of hand. Marketers have reacted to this by simply leaving out references to SF in their promotions wherever feasible.

In a few cases, stories that were clearly science fiction, and became best-sellers over time, lost their SF labels somehow, and became known by their major genre… 1984, for instance, evolving from the science fiction label to that of drama. But more recently, television shows like Lost and movies like The Hunger Games were marketed as drama, with little or no mention of their obvious science fiction elements. The success of some of these programs has suggested that minimizing the science fiction label might be preferable in order to gain an audience.

Maybe it is time, then, to cease using “science fiction” as a genre type, and use a more descriptive sub-genre to accompany the overarching genre types of drama, comedy, mystery, romance, etc. Examining the various story types described by SF leads us to a likely series of sub-genre descriptors, such as: Future, describing any story that takes place beyond present day; Space, a story that takes place beyond Earth; Tech, a story that uses fictional technology; and Alternate, a story with a setting that is like ours, but significantly different (the “parallel universe” scenario). There may be other sub-genre possibilities, but this set would cover most usage.

For instance, a TV program like Eureka would be considered Adventure. Another example, Battlestar Galactica, would be Drama; Gattaca would be Drama; Mission: Impossible would be Adventure; Spaceballs would be Comedy; etc. In each of these cases, the media would be recognized as its primary genre for representation to the public, then narrowed down to its sub-genre for additional detailing: Eureka would be considered (Tech) Adventure (the sub-genre, Tech, modifying the main genre, Adventure); Battlestar Galactica, would be (Space) Drama; Gattaca would be (Future) Drama; Mission: Impossible would be (Tech) Adventure; Spaceballs would be (Space) Comedy; etc.

This new labeling convention would further serve to remove much of the separation between what is perceived as science fiction, and everything else, which would help to erode much of the stigma that separation has caused over the years; instead of being that off-the-wall weird stuff over there somewhere, frequented by oddballs and nerds, SF would be a more integrated part of media in general, enjoyed by anybody.

As in so many other things marketing-related, this constitutes a difference that is no difference; the media itself will not change. But if changing our perception of it makes it more palatable to a larger audience, the effort will have been worth it.