Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 28

June 18, 2015

Jacking in… when? Ever?

It’s one of those favorite icons of science fiction—it’s appeared in books, comics and movies: Jacks hard-wired onto our bodies, through which we plug in wires that make a physical connection from the human brain to outside electronic and mechanical gear. These hardwired connections allow us to “jack in” directly to electronic networks and control our gear with our thoughts.

It’s one of those favorite icons of science fiction—it’s appeared in books, comics and movies: Jacks hard-wired onto our bodies, through which we plug in wires that make a physical connection from the human brain to outside electronic and mechanical gear. These hardwired connections allow us to “jack in” directly to electronic networks and control our gear with our thoughts.

Sure, it looks cool, in a cyborgian kind of way. But how realistic or likely is it that we’ll be able to control computers and machines through a plug to our brains? Will we even want to?

The physical plug, usually depicted in fiction at the base of the skull, through which wires connect to external equipment, has been popularized by movies like The Matrix and countless science fiction books and anime comics. These connections allow the users to operate machinery as if it is part of us, to tap into sophisticated sensors and data-streams, and to communicate with others as if we are telepathic.

Plug technology is over a century old—so it’s very familiar-looking to the viewer—but in fact, little is shared about exactly how the wiring to the brain is actually done. It’s up there with warp-speed technology: There’s no real scientific basis for it, but it’s just assumed to be workable, as reliable as plugging in a set of headphones. And looks really cool and cutting-edge.

For the 20th century.

Futurologist Ray Kurzweil recently said in a presentation that, in 15 years, humans will have nanobots implanted into our brains that will allow us to wirelessly connect to the internet. This is a clearly a modernization of the plug idea, making it a wireless connection instead… but it still skips a vitally important step: Exactly how will that information be passed?

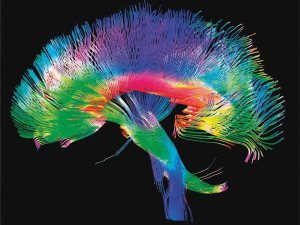

Most people would be surprised at how little we actually know about how the brain works. (And not just the human brain… any creature’s brain.) We know basic mechanical information, sure: We know how it’s shaped, we know what it’s made of. Over the years, we’ve managed to figure out (mostly) what parts of the brain control what functions of the body.

Most people would be surprised at how little we actually know about how the brain works. (And not just the human brain… any creature’s brain.) We know basic mechanical information, sure: We know how it’s shaped, we know what it’s made of. Over the years, we’ve managed to figure out (mostly) what parts of the brain control what functions of the body.

But exactly how those parts are controlled? Well, we’re pretty sure electro-chemical energy is involved. And other chemicals exchanged throughout the brain impact the electro-chemical signals… somehow. So that all those… uh, neurons can exchange… signals that mean… uh…

And that’s where we full-stop. Scientists still don’t know what the code used by the brain’s neurons says. They’re not sure how the neurons interpret it or know what to pass on to which neurons. They’re not sure how or where that information is stored. And they haven’t the foggiest idea how to read it externally.

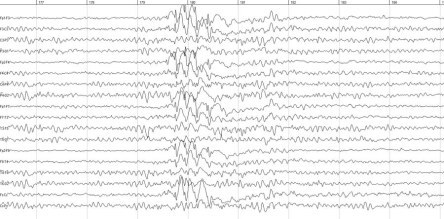

When we try to record the information being passed around in the brain, the best we can get is this:

So far, our best brain-electronic interface—the lowly electrode—can pass simple digital information (1 or 0) based on simple input (is the one signal I’m designed to monitor present, yes or no?). To be fair, that’s not as dismal as it sounds: Scientists have used this digital system to attach hearing aides directly to aural nerves, allowing the owner to receive a signal that roughly simulates the operation of the human ear, and allowing them to “hear” sounds through the hearing aid. Similar experiments are in the works to do about the same with light, and provide a very limited ability for the user to see simple shapes.

So far, our best brain-electronic interface—the lowly electrode—can pass simple digital information (1 or 0) based on simple input (is the one signal I’m designed to monitor present, yes or no?). To be fair, that’s not as dismal as it sounds: Scientists have used this digital system to attach hearing aides directly to aural nerves, allowing the owner to receive a signal that roughly simulates the operation of the human ear, and allowing them to “hear” sounds through the hearing aid. Similar experiments are in the works to do about the same with light, and provide a very limited ability for the user to see simple shapes.

But these are still direct connections, passing on ones and zeros to an individual neuron to represent a “hit” of data. That’s a long way from telling external monitors much about the girl who just ran by us, or how nice the flower bed smells, or whether we need to turn left or right at the next light.

In order to share real data and be able to control sophisticated systems with our brains, we’ll need to take a quantum leap beyond what we know about how the brain works, how it shares and stores its coded information, and how we can understand and share that code with the outside. This isn’t like progressing from a match to dynamite; it’s like jumping from fire to fusion.

And ultimately, direct-to-brain connections to control machines may be a waste of effort. A far more efficient method may be simply imbuing machines with enough intelligence to know their jobs, and to need minimal guidance from humans at all. In Marvel’s Iron Man movies, for instance, Tony Stark uses a sophisticated artificial intelligence named JARVIS, which can control his house, assist Tony in the lab with his experiments, and monitor and assist in the live operation of the Iron Man suit. It can take minimal direction or parse complex commands, monitor Tony’s visual and audio cues (and health data) to anticipate his immediate needs before he articulates them, and converse with him in a colloquial language.

And ultimately, direct-to-brain connections to control machines may be a waste of effort. A far more efficient method may be simply imbuing machines with enough intelligence to know their jobs, and to need minimal guidance from humans at all. In Marvel’s Iron Man movies, for instance, Tony Stark uses a sophisticated artificial intelligence named JARVIS, which can control his house, assist Tony in the lab with his experiments, and monitor and assist in the live operation of the Iron Man suit. It can take minimal direction or parse complex commands, monitor Tony’s visual and audio cues (and health data) to anticipate his immediate needs before he articulates them, and converse with him in a colloquial language.

Thanks to JARVIS, Tony Stark doesn’t need a physical connection to the internet. He just needs to wonder aloud, “What’s the current population of Carson City, Nevada,” “How many species of mosquito around here can carry Dengue fever” or “Any babes around here I haven’t hit on yet?” and JARVIS will tell him.

One of my favorite moments of Marvel’s The Avengers is when Tony must catch a nuclear warhead and fly it away from New York City. Formulating a quick plan, he tells JARVIS: “Put everything we got into thrusters!”

JARVIS, easily anticipating him, simply replies: “I just did.”

Hell, even the Waldo in Tony’s lab (lovingly referred to as “Dummy”) is smarter than most dogs. With AIs as smart as that, who needs to “jack in” to anything?

The other supposed use of physically connecting to our machines would be to physically control devices that need human guidance. I’d submit that, with a good-enough AI, there won’t be many machines that can’t control themselves better than any human could, again, with minimal monitoring and guidance. Automobiles are a perfect example: We’re already working to give our cars the ability to drive us around with minimal direction and independent decision-making ability to choose its route or avoid problems, traffic or obstacles. They are well on the way to being able to drive all of us around inside of a decade.

And look at modern fighter craft, so powerful and complex that they cannot be controlled by humans without a significant amount of computer control and translation, and are capable of recovering the craft independently in the case of a pilot error or incapacitation. Soon, many other machines that are manually manipulated by humans will be able to do their jobs independently, too.

And look at modern fighter craft, so powerful and complex that they cannot be controlled by humans without a significant amount of computer control and translation, and are capable of recovering the craft independently in the case of a pilot error or incapacitation. Soon, many other machines that are manually manipulated by humans will be able to do their jobs independently, too.

And it’s important we move to this step, because our machines are already better than humans at parsing piles of data, making complex calculations and executing macro and micro movements, able to execute hundreds of precise decisions in the time it takes people to make one or two general decisions (that is, after all, what we designed them for). With that kind of speed, it makes more sense to give machines the ability to work independently and anticipate our needs, rather than having to wait for pokey humans to give them instructions, one line at a time, and essentially waste all that potential efficiency.

So, fine: It looks really cool to run wires into your body and control giant robots, experience the Matrix or have telepathic conversations. But instead of the crude-but-quaint 20th century concept of connecting RCA plugs to our necks and trying to think our instructions to our machines, we should be concentrating on making our machines smart enough to do their jobs on their own, without our direct input… and just an occasional helpful instruction, like pointing and saying “You missed a spot.” That’s where the cool technology is going in the 21st century.

So, fine: It looks really cool to run wires into your body and control giant robots, experience the Matrix or have telepathic conversations. But instead of the crude-but-quaint 20th century concept of connecting RCA plugs to our necks and trying to think our instructions to our machines, we should be concentrating on making our machines smart enough to do their jobs on their own, without our direct input… and just an occasional helpful instruction, like pointing and saying “You missed a spot.” That’s where the cool technology is going in the 21st century.

June 16, 2015

Remember When

Nail head… meet hammer. I’m with you, Dan: Let’s have new movies, not endless reboots of old ones.

Originally posted on Winter Hill:

Originally posted on Winter Hill:

A man stalks through the jungle, hunting an animal. He feels something drip on his hand and looks down. Blood. The droplet runs left off, down the wrist. Another drop hits – this one falls right instead. It’s just like that really great scene in Jurassic Park, but instead of water; blood.

I went to see Jurassic World at the weekend.

It wasn’t good. It wasn’t bad either. It was terrible mediocre, but it got me thinking. The dramatic tension in the film was undercut at every possible moment by a reference to the original. So we have the visitors centre, the goat, chaos theory, even the jeeps from the first film make an appearance. All seemingly there to say, ‘Hey guys, remember this? It was pretty good, wasn’t it?’ Jurassic World, as it turned out, wasn’t there to outdo Jurassic Park, but exists soley to remind us that Jurassic…

View original 270 more words

June 14, 2015

Poor Tim Hunt. Poor us.

I feel for Tim Hunt. This Nobel laureate recently made a bad joke at a meeting about women in science, which was snapped up by social media, taken out-of-context (like anyone could have believed he was serious making those comments), and used as justification to force him to resign from his position at University College London.

I feel for Tim Hunt. This Nobel laureate recently made a bad joke at a meeting about women in science, which was snapped up by social media, taken out-of-context (like anyone could have believed he was serious making those comments), and used as justification to force him to resign from his position at University College London.

Let me tell you about my trouble with girls. Three things happen when they are in the lab. You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you, and when you criticise them, they cry.

I mean… yeah. Apocalypse Now.

Hunt’s plight isn’t isolated. Sometimes it seems the whole point of social media is to find things that can be shared without context and made viral, in order to shame or ruin others. In an atmosphere like that, it’s a wonder anyone is willing to speak in public at all.

I guess I should be glad that I’m not famous; otherwise, the comments I’ve made in the past about workplace (lack of) equality fostered by a fashion double-standard would have been twisted around by social media and gotten me sacked from my job.

I guess I should be glad that I’m not famous; otherwise, the comments I’ve made in the past about workplace (lack of) equality fostered by a fashion double-standard would have been twisted around by social media and gotten me sacked from my job.

Or that some other comment I’ve made as an aside, as a joke, as a snide criticism—picking on a politician, ridiculing a trend, calling out the irony of an incident—would have labeled me a crackpot or a subversive (or just a not-politically-correct person) and ruined my life.

(On the other hand… maybe I could use the publicity.)

(Kidding.)

(Probably.)

Actually, the one silver lining of this incident is that Hunt isn’t as doomed as he says he is. Wait about two years, and no one will remember his gaffe, social media will be screaming about some sports figure and his recent dolphin-skinned jacket scandal, or the latest medical findings that Chilean vodka cures shingles, and Tim will glide into a new position and resume his life. But yeah, he’ll have to wait out the well-documented short memory of the public before he can do that.

And we’ll have to wait out whatever valuable research and discoveries he may have made, or the development of any students or researchers he may have mentored, in the meantime… which means we’ll all pay for this incident.

June 11, 2015

Best A.I. in the movies?

There’s an interesting poll up on Hubpages, asking visitors to vote on the best movie about Artificial Intelligence so far. It’s notable for its fairly comprehensive list of excellent movies (if I was to make a suggestion, I’d say Colossus: The Forbin Project and Bicentennial Man should rightly have been included on the list… but to be honest, if we included every movie with a robot in it, this list would be ungodly huge), but I think it’s also notable for the poll’s results so far.

There’s an interesting poll up on Hubpages, asking visitors to vote on the best movie about Artificial Intelligence so far. It’s notable for its fairly comprehensive list of excellent movies (if I was to make a suggestion, I’d say Colossus: The Forbin Project and Bicentennial Man should rightly have been included on the list… but to be honest, if we included every movie with a robot in it, this list would be ungodly huge), but I think it’s also notable for the poll’s results so far.

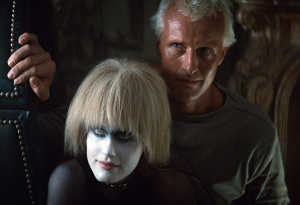

As of this writing, Her has garnered the most votes, as high as twice the votes as Ex Machina and Blade Runner, the next-highest runners-up. I admit to being a bit surprised that Her has polled so well, if only because of its lackluster performance in the box office. But then, the movie did highlight the very personal (and even intimate) relationship between a human and an AI… a bona-fide inter-species love story, in which both characters—human Theodore and AI Samantha—grew and developed during their whirlwind romance. Ex Machina, while it flirted with inter-species feelings, and at least the possibility of intimacy, nevertheless never takes that plunge, preferring to remain a purely intellectual exercise instead.

Did Her get my vote? No; I gave my vote to Blade Runner, the story of robot slaves desperate to risk all for a chance at an extended life of freedom. Though intimacy isn’t part of Blade Runner, it’s no less emotional, following the robots Roy, Leon, Zora and Priss as they try to reach their creator to give them more life… and policeman Deckard and his growing love for Rachel, a robot that thinks it’s a human until the truth is rudely presented to it. The fear and anger of the freedom-seeking robots—enough to kill—is as intense as Rachel’s devastation at the collapse of her reality, and it’s very easy to empathize with their plight. To me, AIs that the audience can fully empathize with make for a pretty powerful story.

Did Her get my vote? No; I gave my vote to Blade Runner, the story of robot slaves desperate to risk all for a chance at an extended life of freedom. Though intimacy isn’t part of Blade Runner, it’s no less emotional, following the robots Roy, Leon, Zora and Priss as they try to reach their creator to give them more life… and policeman Deckard and his growing love for Rachel, a robot that thinks it’s a human until the truth is rudely presented to it. The fear and anger of the freedom-seeking robots—enough to kill—is as intense as Rachel’s devastation at the collapse of her reality, and it’s very easy to empathize with their plight. To me, AIs that the audience can fully empathize with make for a pretty powerful story.

But ultimately, there are a number of deserving movies on this list… and at least one undeserving, I’d say, as they really don’t present what I’d consider a realistic or convincing AI at all. Terminator, I’m looking squarely at you: Sorry, but I’ve never bought the idea that a truly intelligent machine would conclude that the best way to get to the future was to wipe out humanity, the most clever, able, and ultimately manipulable creature on this planet. Period.

Also, I’d make a substitution which might initially surprise you: Replacing 2001: A Space Odyssey with its sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact. Bear with me: Though 2001 introduced us to the HAL 9000, and showed us his efforts to kill the astronauts on the Discovery (and his own sad demise), 2010 presented us with the reasons behind his actions, and in allowing HAL to choose to act on his own behalf or on the crews of the Discovery and Leonov, gave us so much more about the intelligence behind HAL’s unblinking eye. It was therefore a much more powerful AI story than its predecessor had been.

At any rate, the poll is a great jumping off point for the depiction of AI in the movies.

June 8, 2015

The Martian is coming!

The Martian, based on the phenomenal book by Andy Weir and starring Matt Damon, is in theaters this November. I can’t wait!

We need a renaissance…

“We need a renaissance of wonder. We need to renew, in our hearts and in our souls, the deathless dream, the eternal poetry, the perennial sense that life is miracle and magic.”

“We need a renaissance of wonder. We need to renew, in our hearts and in our souls, the deathless dream, the eternal poetry, the perennial sense that life is miracle and magic.”

~ E. Merrill Root (1895-1973)

This quote was recently posted to Facebook by futurist Alex Michael Bonnici, for other futurist fans (he called out a set of co-authors, who had used this quote in one of their books). When I read it, it gave me pause. But maybe not for the reason Alex intended.

For though it’s a nice statement, I’m not sure it’s the right approach for the future. In fact, the idea that “life is miracle and magic” may have backfired on modern civilization, which seems to be backing away from life, technology and the future because it no longer looks like miracle and magic to them.

The 20th century was full of amazing advances in technology, giving us electronics and global communications technology, new forms of games and entertainment, robotic factory workers, powering our homes with the atom and stepping on the Moon. For a time, it seemed there was nothing we couldn’t accomplish. Even the problems that followed those advances—pollution and the increasing damage to the environment—seemed only a nuisance that was easily fixed with a little effort.

Here in the 21st century, we are running headlong into incredible challenges, technological, social, financial and ecological. But the “little effort” needed to fix those things has been put off, or the responsibility shifted to others. The most common response to these challenges seems to be a denial that there are problems, followed by concerted efforts to turn back the clock to simpler times… innocent times… the times when everything felt like magic.

When we were kids.

As a result, we have allowed the continued ruination of our ecosystem in order to drive fast cars… we have resisted heightened security systems because it delays us in the cashier line… we argue gun laws because our right to shoot guns is cooler than your right to not get shot… we fight public surveillance systems because we are afraid to be caught doing things we’re not supposed to be doing, like skipping out of work to see the game or dallying with people we’re not married to. We are still living like children, and resisting anything that will force us to grow up… including doing the adult work needed to solve our problems.

The adult Peter Pan: Unfortunate icon of 21st century Americans.

Even our entertainment backs up our desperate grip on childhood, rehashing and remaking the simple stories of our youth, making live-action versions of fairy tales and showing us characters that never grew up, or who had to return to their childhood to be fulfilled… a world of childish monsters, superheroes and Peter Pans who refuse to leave Neverland.

But we simply can no longer afford to live like children, caring only for the cool stuff and ignoring the rest, as if some authority figure or “parent” will fix it for us. We are the parents. It’s our job to do the fixing.

So, with respect to Root (and Alex), I say:

We need a renaissance of responsibility. We need to put aside the dreams and poetry of our innocent and oblivious childhoods, understand that the problems of the world are not going to fix themselves, and accept our responsibility in getting the job done.

No, it’s not as much fun as partying in a Neverland existence. But when the rain comes, we’ll be glad we got serious for a time and fixed the roof.

The Onuissance Cells tell the story about the Age of Responsibility, or Onuissance, that will save our future. These are my earliest stories, and they are free to download.

The Onuissance Cells tell the story about the Age of Responsibility, or Onuissance, that will save our future. These are my earliest stories, and they are free to download.

June 3, 2015

“Diverse” to who?

An article on the IO9 web site  has some interesting things to say about the concept of diversity in books, and how the target shifts so significantly depending on whose perspective is involved. M Sereno made the following comment at Book Smugglers:

has some interesting things to say about the concept of diversity in books, and how the target shifts so significantly depending on whose perspective is involved. M Sereno made the following comment at Book Smugglers:

What this word means for me is lingo specific to Anglophone SFF, for “outside the majority” or “from the margins” in relation to the white, cis, straight, male, Anglophone, western experience — as Aliette said, outside these axes of privilege. I use it the way I use terms like “third world” or “global South”; they are imperfect and lose a lot of nuance, they’re based on a certain frame of reference outside of which they don’t mean much. They flatten us.

(Read more in the article.)

This has a lot to do with why the term “diversity” frankly bothers me when I write, or read others’ writing. Generally, it feels like it’s doing more to draw attention to the problem than it does to mitigate it.

When most writers, companies, organizations, etc, talk about diversity, I often get the feeling they are saying: “We have these things that White men have, but we want to offer them to non-White people too.” Which is not the same as saying, “Here’s something for everyone”… it’s closer to “Here’s something we made for you people who normally don’t get it.”

And the problem with that is, it tends to (pun fully intended) color the offering somewhat. Instead of being for everyone, it makes a point of being for Black people, or for women, or for LGBTs, or for seniors, etc… and suddenly it becomes no longer suited for White men. It is still exclusionary; it’s just excluding a group that isn’t usually excluded.

A lot of fiction strikes me this way: I run across a character or set of characters, and no matter how much care goes into them, I still feel like I’m reading characters that were shoehorned in to fit someone’s idea of equal opportunity quotas. Much like author Ben Bova’s Frank Colt character, a regular in his Chet Kinsman novels: A Black man who always made a point of mistrusting White men and expecting racist attitudes and actions directed at him… to the extent that his “angry Black man” attitude was often more uncomfortable to me than that of any other character of any other race or sex.

And I realize that those attitudes existed then, and exist now… I realize that men like Colt, who distrust non-Blacks, existed then and now… but the way Bova wrote Colt made him constantly, intentionally and vocally adversarial, even in instances when there was no need for the race issue to be brought forward (including, often, with his friend Chet). He was racism’s intentional poster boy (pun also fully intended), and came across as a stereotype, himself. Reading him, you just found yourself wanting to shout into the book: “DUDE! Calm the fuck down.” If Colt represented diversity, he was the kind of diversity that turned off people who wanted to see diversity.

When I’ve created my characters in the past, the first thing I’ve always tried to do is to allow my developing characters to “spontaneously” become any sex, race or creed that seemed likely—and even to allow them to occasionally be unlikely—just to add a different new element to the story. It was like I was intentionally rolling mental dice for each character, so as not to end up with the same combinations of predictable characters and groups.

On the other hand, this method doesn’t automatically mean you end up with a “rainbow club,” because after all, we still see certain groups dominate certain regions, professions, interests and activities. (You won’t see a mixed group of people at a KKK meeting.) But I also often write of the future, and as time has progressed, many of those old regions, professions, interests and activities have seen a more diverse set of people entering into them; so that, too, has to be taken into account…

As you can see, it’s a very complicated process, and one that can come off as strained to some, bland to others, and just plain insulting to somebody, depending on their point of view. It’s like a target that’s flying, rotating, changing color and fading in and out of reality as you aim at it. And most importantly, if you don’t develop the proper “voices” for the characters, they’ll all just sound like they’re from the same neighborhood anyway… and your attempt at diversity results in a Minstrel show.

As you can see, it’s a very complicated process, and one that can come off as strained to some, bland to others, and just plain insulting to somebody, depending on their point of view. It’s like a target that’s flying, rotating, changing color and fading in and out of reality as you aim at it. And most importantly, if you don’t develop the proper “voices” for the characters, they’ll all just sound like they’re from the same neighborhood anyway… and your attempt at diversity results in a Minstrel show.

When it comes down to it, applying diversity to a story is necessary for realism—and asking for trouble—all at the same time. And since real life is the biggest diversity crap-shoot, there’s just no wrong or right answer… literally anything goes. And sometimes an author needs to embrace that randomness and just do their story… to avoid driving themselves crazy.

Finally: This is my favorite part of the IO9 article, at the end:

Also, Cecilia Tan quotes Sarwat Chaddah, who was told by a bookseller, “We don’t need your book because we don’t have any Indians in our community.” To which Chaddah replied, “I bet you don’t have any hobbits either.”

June 1, 2015

San Andreas: Day After Tomorrow, all over again

What is it about ridiculously over-the-top disaster movies that people just have to watch? Why did someone think a movie patterned after the wretched excess of The Day After Tomorrow was going to be a good thing?

What is it about ridiculously over-the-top disaster movies that people just have to watch? Why did someone think a movie patterned after the wretched excess of The Day After Tomorrow was going to be a good thing?

No, no answers to these rhetorical questions. I have nothing more to say.

May 30, 2015

Lightweight High-Energy Liquid Laser (HELLADS) prepared for live fire tests

Project leader Chris Knight is expected to attend, though currently his whereabouts are unknown.

Project leader Chris Knight is expected to attend, though currently his whereabouts are unknown.

(Real article is here.)

May 29, 2015

Communication with alien species

The 2011 Scientific American article A Brief Guide to Embodied Cognition: Why You Are Not Your Brain has a lot to consider when we contemplate the difficulty we’re likely to have in communicating with aliens… or, for that matter, with certain of our own terrestrial co-species.

The 2011 Scientific American article A Brief Guide to Embodied Cognition: Why You Are Not Your Brain has a lot to consider when we contemplate the difficulty we’re likely to have in communicating with aliens… or, for that matter, with certain of our own terrestrial co-species.

Put simply (in deference to Kent), the article discusses how our thoughts are defined and guided by metaphors, many of which are dictated by physical experiences based around human physiology.

We understand control as being UP and being subject to control as being DOWN: We say, “I have control over him,” “I am on top of the situation,” “He’s at the height of his power,” and, “He ranks above me in strength,” “He is under my control,” and “His power is on the decline.” Similarly, we describe love as being a physical force: “I could feel the electricity between us,” “There were sparks,” and “They gravitated to each other immediately.” Some of their examples reflected embodied experience. For example, Happy is Up and Sad is Down, as in “I’m feeling up today,” and “I’m feel down in the dumps.” These metaphors are based on the physiology of emotions, which researchers such as Paul Eckman have discovered. It’s no surprise, then, that around the world, people who are happy tend to smile and perk up while people who are sad tend to droop.

Many of these metaphors are directly related to how the human organism responds to specific stimuli:

• Thinking about the future caused participants to lean slightly forward while thinking about the past caused participants to lean slightly backwards. Future is Ahead

• Squeezing a soft ball influenced subjects to perceive gender neutral faces as female while squeezing a hard ball influenced subjects to perceive gender neutral faces as male. Female is Soft

• Those who held heavier clipboards judged currencies to be more valuable and their opinions and leaders to be more important. Important is Heavy.

• Subjects asked to think about a moral transgression like adultery or cheating on a test were more likely to request an antiseptic cloth after the experiment than those who had thought about good deeds. Morality is Purity

What’s significant here is that an alien visitor to our planet may not share the same physiological form as humans, and therefore these metaphors might make no intrinsic sense to them… at least, not without extensive study of our physiological form and our psychological and social makeup to be able to recognize these metaphors and their significance. Similarly, without thoroughly understanding their physiology, psychology and social makeup, we would have as much trouble understanding them. We describe anger as making us “hot”; but if an alien responds to anger by becoming “flat” or “clean”, how do we communicate these feelings to each other?

He’s so happy to see me–YOWTCH!

Here’s some purely terrestrial examples. A smile, something humans use to indicate friendship, is used by Chimpanzees to indicate fright or nervousness… think of the consequences of misinterpreting that in a delicate situation. And, of course, many animals’ faces suggest to us permanent smiles (or frowns), causing humans to interpret dolphins, for example, as “happy creatures,” or Koalas as “sad,” and consequently (and, apparently, often) make the wrong assumptions about their physical or mental state in an encounter.

This is more fodder for the argument that, if we have this much trouble understanding creatures on our own planet that at least have some similarities to humans, how can we expect to be able to communicate with aliens? Sure, we may manage to cobble together a common form of language through mathematics, but will we understand the significance of a statement like “There are an awful lot of you humans”? Are they complimenting us, or suggesting that we begin culling ourselves? Will they understand when we bend closer to examine their appearance? Are we curious, lazy, hard of hearing, or hungry?