Tim C. Taylor's Blog, page 17

January 27, 2012

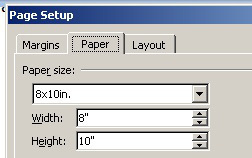

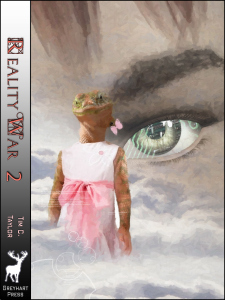

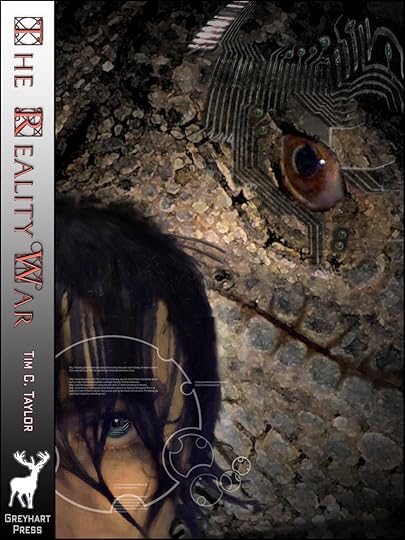

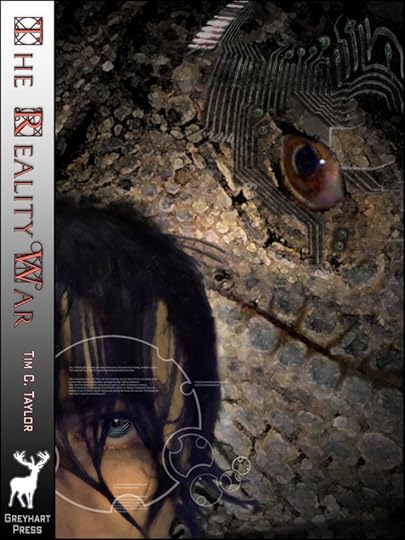

Fancy a free read? Calling beta reviewers for The Reality War

Book1: The Slough of Despond

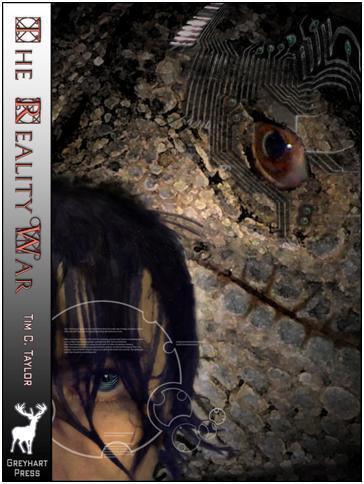

My debut novel comes out on February 9th, a story of time travel and adventure called The Reality War. I'm looking for beta reviewers: people who read a free copy, and in exchange, post an honest review on Amazon (and possibly elsewhere too) when the book is launched. There's no time limit, or expectation that you will post a positive review regardless of what you thought.

If you're interested, mail me at tim at timctaylor dot com or tweet @TimCTaylor, and let me know whether you'd like a Kindle, PDF, or ePub version (ePub is suitable for iPad, iPhone, Kobo, Nook, Sony eReader).

There's some help on writing reviews here, and more information about the book here.

As an extra bonus, book1 gives details on how to download a free copy of book2.

January 26, 2012

The Pilgrim's Progress and The Reality War: Part 2

Now that we've briefly seen something of The Pilgrim's Progress, and its successes and criticisms (see Part 1), let's see how they influence The Reality War.

[By the way, I've illustrated this post with some lovely artwork. You can click on the images to bring up a larger version.]

Right from the start, I took the idea of a spiritual journey from despair toward enlightenment. My key difference is that I have de-coupled my journey from being a specifically Christian journey. I fear that if Bunyan were to read this, he would reject this approach, believing that without God, any spiritual journey is meaningless, a dangerous diversion from the one true, narrow path.

The Slough of Despond

In Bunyan's book, the first obstacle, is the Slough of Despond, a metaphorical bog that many of us sink into with little hope of escape.

My two principal characters start their journeys in this mire: Radlan, the human character, is a drunken failure in virtual exile, while non-human Karypsic is embittered, ineffectual, and humiliated. Of course, no one enjoys reading novels about losers and whiners, and so our main characters are offered both redeeming qualities and helping hands out of their respective Sloughs of Despond.

In The Pilgrim's Progress, Christian is offered divine help out of the mire; the idea being that that helping hand is always there for those who seek it. This is true of my novels, several helping hands being available until each main character seizes one and allows him to be hauled up.

You will notice I've just written about two principle characters: one human and one not. This is where I break away from The Pilgrim's Progress to use the science fictional idea of parallel universes. First and foremost, I do this for fun.

Book2: The City of Destruction

This is a good point to respond to the first criticism of The Pilgrim's Progress: that it is crude. I had some thematic and scientific ideas in mind as I wrote The Reality War. But just as Bunyan wrote his book to be a spiritual manual for regular people, I wrote mine to be an enjoyable read for regular people. I wrote these novels as entertainment, not to deliver a message. To my mind, I only earn the right to play with themes and scientific speculation once I have delivered an exciting read.

Although I write about parallel worlds because I hope that makes for an exciting story, but I also did so deliberately to take the ancient story idea of a spiritual journey towards enlightenment, and present it in a new light.

How so?

In The Reality War: the Slough of Despond, our main human character, Radlan, does something he shouldn't. In many ways, he does the right thing, the honourable thing. Still, he is not supposed to choose that path. The multiverse is disturbed. Other realities, such as one where reptiles are the dominant species, become more likely; the probability that humanity evolved becomes increasingly unlikely.

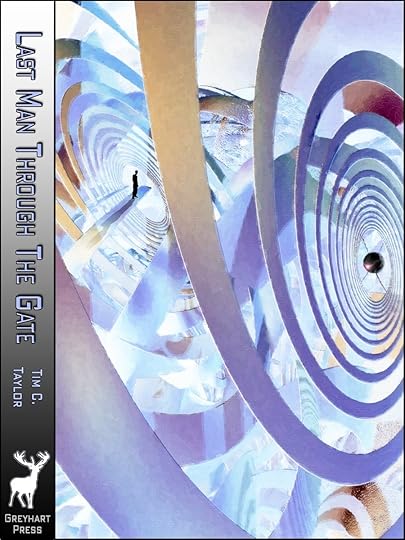

Reality has splintered, leading to the setting for Last Man Through the Gate

Take a look at the cover art for my novella, Last Man Through the Gate. See all those swirling paths? Radlan did that. Last Man is a standalone story, but the worlds it travels through were made possible by Radlan.

For a while, it seems that when the multiverse settles once again into equilibrium, it looks as if the human existence we are familiar with will never have existed. Desperate measures are called for…

I'll stop there. We're getting into plot, where I want to look at theme.

Karypsic (the principal non-human character) and Radlan are parallel characters. Similar things happen to them. There are similarities in the 'people' around them and the obstacles they face; they even dream of each other. This is no coincidence. Radlan and Karypsic, together with their families, friends (and enemies!) are the unwilling champions of the two front runners in the race to become the dominant reality.

The Reality War: the clue's in the title.

Even as each character is progressing through a journey like Christian's in the Pilgrim's Progress, the Reality War is the big background event. As the books progress, the war comes increasingly to the fore. The characters gain in balance, wisdom, and empathy. They improve, moving along the path toward enlightenment. But there are no easy answers here, the Reality War is not a children's game where everyone wins a prize. There can be only one winner, and oblivion is the fate for the loser. The tragedy of the story is that even as we grow to care about both sets of characters, we become convinced that one of them is doomed. Spiritual enlightenment is not enough in this series; no matter how praiseworthy your journey might be, blind chance and physics can kill you anyway.

So for the third criticism of The Pilgrim's Progress (that Christian has to die in order to 'win' — although some would dispute this reading of The Pilgrim's Progress), I alter the message. With Bunyan and Lewis, you have to complete your spiritual journey in order to die and 'win'. In my series, you can only 'win' if you make progress along your spiritual journey, but you might 'lose' anyway, even if you do make good progress. I chose to put my characters in an unforgiving and perilous multiverse to keep you guessing about how the story will end. It's a good job I didn't write these books to convey some kind of message, because it would be a stark one if I did!

Giant Despair and Doubting Castle: Radlan experiences this literally

Since we're drawing references to a few common criticisms of The Pilgrim's Progress, let's draw to a close with the people left behind: women and children. It's difficult to say much about how I deal with this without giving away spoilers. While the two main characters are males, very loosely based on Christian, they only make progress when they recognize and accept help from their families. In fact, the families move as a group. When one part of the family strays off the narrow path, the whole family is dragged back until they find their way back to the path and set off again.

Such a focus on family values sounds simple and rather traditional, and I suppose it is. Don't forget, though, that my story has time travel, parallel worlds, and alternate histories with alternate individuals. Let's just say that some of my family groupings would be impossible without these science fictional devices!

I'll post more about locations another time. If you know Bedford or Elstow, you will think you recognise some of the locations. There are differences, though. The descriptions of The Bear on Bedford High in the early 90s are pretty much how I remember it, even down to the CDs in the juke box. But many details are altered. My descriptions of the Bunyan's Mead cottages don't match what I see when I walk through Elstow High Street. In fact, they don't even stay the same as the book progresses. Reality has become unstable. As the book starts, the 1990s Bedford that I remembered never existed, replaced by something subtly different. Which version history will crystallize out of the Reality War? Read and find out!

So that's your lot: probably more than you ever wanted to know about John Bunyan and The Pilgrim's Progress.

In conclusion, The Reality War does not carry an explicitly Christian message, but some of the ideas behind The Pilgrim's Progress, and many of the real locations too, were woven into the fabric of my stories. In the end, though, I wrote The Reality War to be entertainment, and if you read it, entertained is the reaction I hope you feel.

Tim

January 24, 2012

The Pilgrim's Progress and The Reality War: Part 1

John Bunyan

When talking about my science fiction novel series, The reality War, I've sometimes mentioned a connection with John Bunyan and his hugely popular book The Pilgrim's Progress (1678). Several people have asked me to explain more about that connection. Are my books simply a retelling of The Pilgrim's Progress, making them a Christian allegory dressed up in science fictional clothing? Or are they an anti-Christian allegory? There again, perhaps the Bunyan connection is no more than a marketing ploy, a few words crudely bolted onto my story, and just as easily taken away again?

In this post, I'll look at The Pilgrim's Progress and pick out a few common criticisms as a tool to examine it in a little detail. In the following post, I'll show some of the connections between The Reality War series and The Pilgrim's Progress. But first…

The Concise Answer

Book1: The Slough of Despond

How are my books connected to The Pilgrim's Progress? The concise answer is that the thematic idea of a spiritual journey operates at a deep level across my books, and was always present in my mind as I crafted the story. Readers hoping for a faithful retelling of Bunyan's plot will be disappointed, but without The Pilgrim's Progress as my blueprint, I would have written a very different book. So there is a deep thematic link, even though I don't spell out a specifically Christian journey.

There are more literal connections too, both in sharing the same geographical setting (Bunyan used real locations in the Bedford and Elstow area) and in a few specific actions of my characters that I can't explain without giving away spoilers.

Elstow Green and the Moot Hall

The events of my book play out in Bedford and Elstow, the places where Bunyan lived and worked. Key events play out in a row of cottages called Bunyan's Mead. They didn't take that name in the seventeenth century, of course, but the cottages predate Bunyan. In other words, when Bunyan lived in Elstow, he would have walked past those same cottages every day. Then there's a scene in Elstow Green, a real place where I picked conkers with my son last year, and where my wife danced as a girl in the May Day celebrations. It was here in Elstow Green where, as a young man playing a bat-and-ball game called tipcat, that John Bunyan had a vision from God that placed him upon the narrow path of godliness. It was the annual fair at Elstow Green that Bunyan references in The Pilgrim's Progress, coining the term: Vanity Fair. I could go on. I won't, but if you want to see more of Elstow, the Tudor cottages and Elstow Green, there's a collection here.

As for literal references, I have kept them as deep hints because they are not fundamental to the understanding or enjoyment of my novels. After all, time travel novels have a tendency to drift into over-complexity if you let them; tangents that are potentially confusing need to be stamped out. Nonetheless, if you look for the hints, the time-meddler, Greyhart, may have more than a theoretical knowledge of Elstow in the seventeenth century.

A brief history of The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress first edition. I think my cover art is better!

Bunyan's book has been phenomenally successful. That's a term bandied about so frequently that it has lost its impact, but phenomenon is the right word to use. A century after first publication in 1678, Benjamin Franklin wrote of The Pilgrim's Progress in his autobiography, speculating that it had been read more than any other book except the Bible. A Google search for "The pilgrim's progress" returns over 3 million hits.

Bunyan's book describes an allegorical journey of a man (Christian) making his assisted way from the sinful world of Man (The City of Destruction) through many obstacles and meeting many characters along the way (mostly those who would lead him off the narrow path, but genuine help is there for those who look for it) until eventually he reaches heaven (the Celestial City — although some interpret the Celestial City more broadly, encompassing those still alive but qualified for heaven).

To modern readers, the allegory may appear crude, but in Bunyan's time, modern readers did not exist. I think Bunyan would have thought of his book as a linked series of parables , a technique for telling a story with a moral that would be very familiar from the New Testament. Bunyan was a Puritan preacher, and I imagine he thought of each chapter as a sermon. Puritanism was an English manifestation of Protestantism that fought successfully for influence over the development not only of modern England, but of America too. You see this Puritanism at work in the text, where Bunyan sets out a path to salvation but only for those who follow the right kind of Christianity. As a Puritan, and himself uneducated, Bunyan was aiming his book at the common man (and, as we'll see — possibly after some prompting — at the common woman too) and not at the educated elite of the land (those who imprisoned him more than once). The apparent crudeness of the allegory may have been a factor in its popularity, not only because it was understandable by simple uneducated folk, but because its lack of (apparent) artifice was popular with educated Protestants who championed the simplicity and directness as virtues.

If at times, the allegory is heavy-handed then that is a charge I dismiss, both because that is a stylistic choice, and because judged within the context of its time and its purpose (ultimately, Bunyan wrote his book in order to save souls) the book succeeded brilliantly. Sophisticated readers have always been quick to condemn populist literature. In recent times, JK Rowling has been rubbished for her crude Harry Potter series, as has Dan Brown with his The Da Vinci Code. Some of that criticism might be well-founded, but in the end it misses the point. Harry Potter and Da Vinci Code were designed to be stories that regular people would enjoy. Bunyan succeeded then as JK Rowling and Dan Brown succeed today.

One thing I've found in my experience with publishing eBooks is that sometimes people are quick to criticise a book for faults they assume it has, without troubling themselves to actually read it. And so it is with The Pilgrim's Progress. When I first read the book, I too thought some of the allegory was crude. I read it in Bedford Central Library, in the local history section. As Bunyan is by far the most famous individual connected with Bedford, I was surrounded by dozens of editions of The Pilgrim's Progress and books about Bunyan and his works. Reading through some works about The Pilgrim's Progress reveals a surprising truth for a work supposedly so crude: learned people over the past four centuries have tried to decode the book's allegory and arrived at different answers, and many of the interpretations are intricate and subtle. For me, that's the killer. An allegory that is open to interpretation cannot be so crude, can it?

Mansplain your way out of that!

Another criticism is that there is a gaping hole in Bunyan's thinking behind The Pilgrim's Progress. Considering the book as a series of parables/sermons rather than a single narrative thread might help to understand Bunyan, but no amount of mansplaining by me or by Bunyan himself really gets him out of this one.

Consider:

In The Pilgrim's Progress, the hero, Christian, hears about the City of Destruction (code for: realises his immortal soul is in peril unless he finds God). He is so terrified that he bids farewell to his wife and children and starts off on the tricky journey that eventually leads to his soul in heaven. He does try to persuade them to come, and does occasionally bemoan their absence on his journey, but there is never any question of him turning back for them.

Mr Great-heart, aid to Christiana

Let's back up a moment. Christian is a father and a husband. In Bunyan's day, that means a heavy responsibility as the spiritual, legal, and financial head of his household. His wife and children rely on him. But Christian is so intent on saving his soul, that he abandons them.Perhaps surprisingly, the accusation that Bunyan had offered no spiritual hope for women in his book was made immediately upon publication. We writers sometimes talk of 'fridge moments': when someone points out a gaping hole in our stories that is so unforgiveable, our only recourse is to repeatedly bang our head against the fridge. If Bunyan had a fridge, I wonder whether it would have had a few head-sized dents.

I honestly don't know. If anyone does know about Bunyan's reaction to this criticism, I'd love to hear about it. Having personal experience with writing a series of time travel novels with a theme of spiritual journey, I know that books can quickly get out of hand in terms of complexity, and sometimes need leading back into a simpler shape to be enjoyed by the reader. That means leaving things out. Perhaps Bunyan deliberately left out the family in order to concentrate onto personal journey that, in his view, everyone must complete on their own. Or maybe I'm just mansplaining J

Bunyan acknowledged this problem and wrote a sequel, where Christian's wife, Christiana, and children set off on their own journey of spiritual salvation. True to the times he was writing in, Bunyan does not allow Christiana to journey without a chaste male mentor and guardian to assist her. This role is provided by Mr Great-heart. You might see a similarity with the name Greyhart. This is no coincidence, but to explain more would be a spoiler.

To journey unto death

Children's author of His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman has written of his horror at much stories of Christian allegory: The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis. In the final Narnian book, The Last Battle, they fight their climactic battle and meet the Christ-figure, Aslan, once again. I remember reading this book in my early teens and thoroughly enjoying it. Pullman's distaste is that in order to be propelled into their final adventure, the human children must first die in this mortal world.

When I first read The Last Battle, I understood a lot of this but was too caught up in the excitement to pay much attention. Looking back now that I'm a father, I also feel uncomfortable with a children's story that could be seen as championing death as the gateway to the best part of your existence.

Whether this is a telling criticism depends upon the depth of your Christian belief (if any). To Lewis and Bunyan, whose belief was absolute, uncomfortable though their belief about heaven and hell might be, it was the ultimate truth and had to be addressed.

The Pilgrim's Progress is no different. Again, treating the book as a single narrative thread, rather than a collection of sermons, may exaggerate this, but the main character's ultimate objective is to die having overcome his obstacles along his journey. Only then can he truly finish his story in the Celestial City.

Wrap-up

So that's your lot: probably more than you ever wanted to know about John Bunyan and The Pilgrim's Progress… unless you're really into Christian religious texts, in which case it was not nearly enough and probably misguided because I am not myself religious.

Now that I've shown a little bit of The Pilgrim's Progress, next time I'll compare it to The Reality War.

January 20, 2012

Publication date set for my first novel

Book1 of The Reality War will be published through Greyhart Press on Feb 9th. Initially released as a Kindle eBook, paperback and other eBook editions will follow. Book2 will be published later in the spring.

Book1 of The Reality War will be published through Greyhart Press on Feb 9th. Initially released as a Kindle eBook, paperback and other eBook editions will follow. Book2 will be published later in the spring.

For more information, see my The Reality War page.

Guest Post: Sample of RJ Palmer's Sins of the Father

We're going to things slightly differently for my latest guest post. Author RJ Palmer has kindly offered us a sample of her forthcoming novel, Sins of the Father…

Lucian whispered something in that nebulous language that Aaron didn't understand, "Bendithia 'r blentyn , achub 'r blentyn."

Lena had only made it a few steps when Lucian stood and began to make his way to the front of the church and Aaron was at first completely confused until he thought that perhaps someone in Lucian's past might have been a practicing Catholic and taught it to the boy. Aaron sat back and observed despite his trepidation to find out what would happen next.

Lena watched Lucian walk past her without acknowledgement and turned to watch him as he made his way to the front of the church.

Aaron began to feel a heavy, electrified feeling in the atmosphere and began to become alarmed though he carefully suppressed it and continued to watch.

Lucian walked up to the front without so much as a bow or a by-your-leave and made his way past the Father who was intoning the prayers. The Father stopped for a moment and looked at Lucian mildly askance and then seemed to smile beneficently and indulgently and tried to speak to Lucian in greeting.

Lucian ignored him completely and walked up to the cross hanging prominently centered on the back wall of the church behind the pulpit.

The Father trailed off in complete confusion and turned around to watch.

Lucian laid his small hands on the cross and screamed his words with his head thrown back and his body tense and taut as a bowstring, "Bendithia 'r blentyn , achub 'r blentyn," And smoke began to rise from the cross on which Lucian's hands rested.

A few people rose and began to mutter, some cried out in surprise and fear as the cross at the centerpiece on the back wall of the church burst into flames.

Sins of the Father

A minister losing touch with his faith…

A severely autistic child with no past, no present and no real future…

An evil older than time itself…

When the boy Lucian is thrown into Aaron's life with nowhere else to go all hell breaks loose and Aaron confronts things he never actually imagined could really exist in an effort to save one small, tortured child.

Author, RJ Palmer

Find out more about RJ Palmer at her blog

RJ's previous novel, Birthright, is available at amazon.com | Smashwords

Why writing a time travel novel is like wearing fresh underwear

One of the finishing touches I'm applying to my forthcoming time travel novel is to add the location and date to my chapter sub-headings. It's not as easy as it looks (as I will explain), and made me think not only of writing tips for novelists, but of lessons about professionalism I learned the hard way in the software industry.

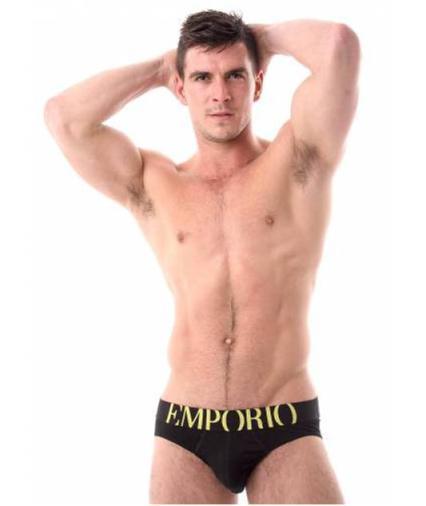

The author, yesterday

My conclusion is that getting the details right in your novel is like putting on fresh underwear in the morning.

Or — if you prefer a more visceral metaphor — not getting the details right in your novel is like wearing yesterday's underwear because you don't think anyone will notice.

So. Er… if I can tear your eyes away from the image, let's get back to my novel, please.

When I entered the sub-heading for my prologue, I put:

Elstow Abbey, 2992

I was happy with that at first. But my novel is somewhat like The Time Traveler's Wife in that the characters are not merely dumped in the past where they fall in love/ try to get back home; instead there are settings in several times and they way they interact is important. Sometimes it's not enough to know the year, I want the reader to be clear on the date too. The potential for excessive complexity is a potential pitfall of time travel stories. Therefore, although I wrote the novel so that readers can tell the date and setting from reading the words, I thought it a good thing to add in these sub-headings as extra help. And I wanted to help, it would make sense to add the date as well as the year.

Adding dates threw up an unexpected problem, the scourge of time travel novelists: leap years!

Although with a time travel story, you can jump in and out of any date you want, for the most part of the book, I keep what the characters call a parallel clock protocol. There is a secret time station in the sleepy English village of Elstow. When people from the 2900′s came back in time to the 1900′s, they kept the clocks running in parallel, exactly 1000 years apart. So when it's Jan 1st 2901 in the future version of this Elstow Abbey Time Station, it is Jan 1st 1901 in the version of Elstow Abbey in the past. If a month later (on Feb 1st 2901) someone from the future wants a chat with the past, the date in the past will be Feb 1st 1901. It's a practical way to run the operation, and keep the sanity of both the characters and the reader (not to mention the author).

Easy.

Except I had this nagging feeling that I needed to verify the effect of leap years. It's at this point that the underwear comes in (or on… but not off, sorry). By this point, my novel had gone past copyediting; the last thing I wanted was to dig up the text again to change a lot of dates. It was very tempting just to leave it as it was because — let's face it — who on Earth is going to actually notice if I write that July 2nd 2992 is on a Tuesday (when as anyone knows, it's actually on a Monday)? Probably some especially pedantic reviewer, that's who, but most readers would never bother to check such details. So why bother checking the dates?

I spent twenty years working for a software business whose products were used by hundreds of thousands of people every day, and whose software needed to be changed constantly and indefinitely to keep up with government rule changes. In other words, the software needed to be robust, and both easy and safe for us to maintain. When I ran the quality department, board members would sometimes ask me what they could do to help improve the quality of our software. My answer was that they should champion professionalism and demonstrate that through their actions at every opportunity.

When, instead, the directors cut dangerous corners, or knee-jerked into short-term solutions, the software development teams would follow their lead and also cut corners. Quality suffered. The reverse was true: when the directors tried to foster a culture of professionalism, software quality rose, especially robustness.

The software teams made scores of decisions every day. They worked best when all the team members knew that if it was a choice between the easy way and the right way, we would go for the latter.

It's the same as Broken Windows Theory, or running late in the morning and putting on yesterday's slightly seasoned underwear, rather than go out through the rain to the garage to get fresh underwear out of the dryer. If you wear yesterday's skankies, chances are that no one else will know (although you can't be sure). You would know, though. And if you cut corners with your clothing, what else will you do the easy way that day? On its own, wearing yesterday's underwear, may seem fairly trivial (I'm guessing it will be the guys who are more likely to agree with that) but it sets you up in a negative mental attitude that's far from unimportant.

So, as you've guessed, I did figure out my leap years, and I'm glad I did because the novel would have been wrong otherwise*. My advice to novelists is to do the same, especially if, like me, you write fantasy or science fiction. If you have a hazy notion of how part of your fictional world operates, then your writing will be vague, even evasive, in that area. Too many areas left unclear and soon the writing is unconvincing. If you don't have a vivid concept of how your fictional world works, then I can tell you one thing for certain: it isn't an interesting place to read about. And you can't come back and fix it at the end either (unless it's the small details) because if you didn't understand your world while you wrote the story, the world will not be woven into your story; it will be nothing more than background scenery.

So, as you've guessed, I did figure out my leap years, and I'm glad I did because the novel would have been wrong otherwise*. My advice to novelists is to do the same, especially if, like me, you write fantasy or science fiction. If you have a hazy notion of how part of your fictional world operates, then your writing will be vague, even evasive, in that area. Too many areas left unclear and soon the writing is unconvincing. If you don't have a vivid concept of how your fictional world works, then I can tell you one thing for certain: it isn't an interesting place to read about. And you can't come back and fix it at the end either (unless it's the small details) because if you didn't understand your world while you wrote the story, the world will not be woven into your story; it will be nothing more than background scenery.

Agile software teams often operate that way. You build another chunk of the software, and don't fret about some of the minor faults because it's more important to build and keep momentum. But there comes a point when the drag and the risk from too many faults left unfixed and questions unanswered means that intelligent teams will stop building more features for a while and concentrate on fixing bugs and making design decisions.

Oh, and for the record. I always wear fresh underwear. Honestly.

* Leap years — what did I get wrong? The year 2000 was a leap year; the year 3000 was not. So my parallel clock protocol (kicking off on Jan 1st 1901/ 2901) worked fine until February 28th, 2000 / Feb 28th 3000. The following date was February 29th 2000, but was March 1st 3000. Since I have dates in 3009, I had to offset them by one day.

The Reality War Book1: The Slough of Despond will be released for Kindle on February 9th 2012 through Greyhart Press. Paperback and other eBook editions will follow.

The Reality War Book1: The Slough of Despond will be released for Kindle on February 9th 2012 through Greyhart Press. Paperback and other eBook editions will follow.

January 17, 2012

I'm interviewed at Susan Ricci's site

I've been interviewed by author and blogger Susan Ricci, where I talk about John Bunyan, my debut novel, lizard-people, Stephen Baxter's Xeelee Sequence and my second novel. And Doctor Who.

I've been interviewed by author and blogger Susan Ricci, where I talk about John Bunyan, my debut novel, lizard-people, Stephen Baxter's Xeelee Sequence and my second novel. And Doctor Who.

Oh, and calculating diastatic enzymes when designing your own beer brewing recipe.

The usual fare, in other words.

Susan writes well-crafted posts, and I invite you to take a look around her site.

Tips on formatting your print book for Createspace and Lulu. Part2: Headers & Footers

Here's the latest instalment in a series of formatting tips. Click on the link to see the previous entries: Part1

Tip#4 Headers and footers

Time to dig out those books from your bookshelf again and take a closer look at the headers and footers. There are a variety of styles, but there are two things that are always true:

There are page numbers (though front matter (e.g. title and copyright notice) is handled differently, as are chapter and part title pages)

Blank pages are always left completely blank (no header; no footer)

Here are some other things you might find:

Name of the book

Name of the author

Name of the story (anthologies and collections)

Name of the chapter (especially with non-fiction)

Header text in in All Caps, Small Caps, or italics to set it apart from the body text.

If there are footers, they tend to only have the page number, and this will usually be centered.

Headers on odd and even pages are mirror images of each other

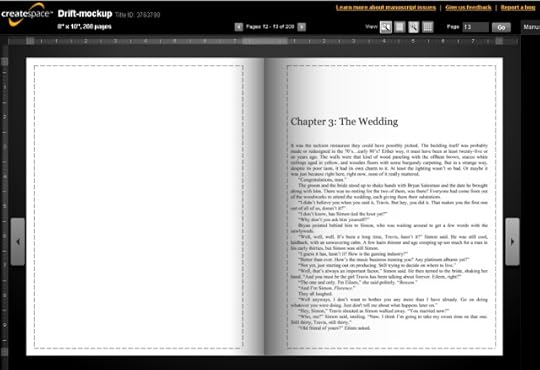

That's quite enough of that. Let's see how that looks in our example book, Drift by Andrew Cyrus Hudson.

Headers & footers in body text. Click for larger image

Here, on pages 6 and 9, we are past the title pages and blank pages we saw earlier, and showing how the main body of the book works. I've taken a standard style of mirrored headers with no footer. Although the headers are mirrored (the page number is always towards the outer edge of the page) the text is not the same. Even pages have the author name, and odd pages have the book title.

I have placed the title in all caps, using the same font as the body text. Because the author's name is fairly lengthy, I decided to keep Andrew Cyrus Hudson in mixed case. Your headers should recede into the background as the reader reads the story, and I judged that this was best served here by using mixed case. It was a close call; keeping all caps or small caps would have helped differentiate the title from the body text. I tried both and thought this looked best.

And that's what you should do, too. Read the advice, look at a sample of books, and then experiment to see what works best.

Before we see how we deliver this in Word, I'll turn the page once more in Createspace's Interior Reviewer tool.

Headers & footers at chapter start. Click for larger image

We've seen this in earlier tips, but it's a timely reminder that in my page layout plan, I decided to set each chapter so it started on an odd (facing) page. When that means a blank page is needed (as here) it should have no header and no footer. The first page of a chapter has no header either. Note that in this book I'm not using footers. If I was (probably with a centered page number) then the first page of the chapter would have the footer and the blank page would not.

Okay, that's quite enough of Createspace for a few moments, let's look at how we set this up in Word.

The first thing you need to know about Word is that in order to format a print book divided into chapters or similar, you need to divide up your Word document into sections. We'll do exactly that in the next tip, but with regard to headers and footers, the important things about sections are:

For each section, you can choose new headers/footers, or carry on the same as the last section.

For page numbers, you can choose to carry on counting from where you left off last section, or restart at a new number (which you would do if you wanted page numbers for you front matter (usually i, ii, iii rather than 1,2, 3)

You can define headers/footers to be different for the first page of a section. That's how we stop the header appearing on the first page of a chapter or part.

Now, let's see some screenshots of this in Microsoft Word 2007. If you have an earlier version of Word, don't worry. Word 2007 introduced the Ribbon, which makes the user experience very different. However, all the facilities I'm about to explain about were there in earlier versions, and so you can learn the concepts and then look at the online help to explain how to access them in your version of Word.

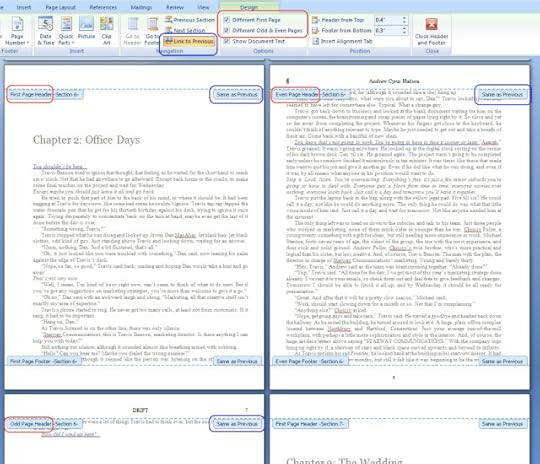

Headers & footers in Word. Click for larger image

Here we have pages 5,6,7, and 8. These pages in Word define what you saw earlier in the Createspace Interior Reviewer. I have clicked in the header area (i.e. the top of the page) to bring up the header and footer tools. This has grayed the main document text, brought up a new menu in the ribbon (Header & Footer Design), and added the pale blue tabs, which give you vital information about how you have defined your sections.

We'll start with the blue tabs. You can see that pages 5,6 & 7 are section 6, and page 8 kicks off section 7. What you can't see is that page 4 was the last page of section 5, and that I have currently got section 6 selected (because I was in chapter two when I brought up the header tools. You can move sections by clicking next/previous section in the ribbon).

Now look at the areas I've ringed in red. On the ribbon, I have set the following options that I'm interested in right now:

Different first page

Different odd and even pages

Now look at the red rings over the pages. I've ringed three of those pale-blue 'tabs'. They read 'First page header', 'even page header', 'odd page header'. This means that section 6 has three different headers, which is precisely what we told it to do as we've just seen on the ribbon.

We only have three pages for this chapter. If we had more, then any following pages would alternate between even page header and odd page header.

To set what goes into the header — in other words, the page number and the title/ author — first of all I have to pick the correct header. If I want to set the odd page header, for example, I need to click the page where the pale-blue tab says 'odd page header'. That will set the header for all the odd pages in the current section.

Next, I click on the header button in the ribbon like this…

Defining header in Word. Click for larger image

Here, I've picked the option for 'Blank (Three Columns)'. To carry on with the odd page header example, I:I

Clicked on the central '[Type text]' and replaced with 'DRIFT'

Deleted the left-hand '[Type text]'

Clicked on the right-hand '[Type text]' and entered the page number. Now in this case I've used a 'quick part' to define a field. If 'quick part' is gobbledygook, don't worry. Page numbers can be tricky, so we'll come back to them in the next tip, once we've dealt with the rest of headers.

We define the even page header in the same way, but with different text and placement.

As for the first page header… Well, I don't want the first page of the section to have any header, so I leave it blank.

Link to previous

If you look at the last couple of screenshots you'll see a ribbon option called 'Link to previous' and in the pale-blue tabs it says 'same as previous'. You need to know how to use this.

Suppose you have 100 chapters, and you want the odd and even headers, I used in Drift , and you want to leave off the header on the first page of a chapter.

That means you must have 100 sections.

Each section must have a separate first page, odd page, and even page header.

That's 300 headers. You really don't want to define each one by hand; you want to define each one just once, right? For that you need 'link to previous'.

Start towards the beginning of your document, at the first place you want to start using the standard headers (ie after the front matter).

Define all three of your headers.

For each subsequent section, instead of defining three new headers, click on the 'link to previous' ribbon button for each heading type and it will inherit what you defined in the previous section for that heading type. (when I say 'heading type', I mean one of odd- / even-/ first-page header).

Continue this all the way through to the end.

An added bonus, is that this means you can alter something about the header (perhaps set to all caps) and the change will be reflected in all the linked headers.

One gotcha here is that the 'next section' / 'previous section' buttons on the ribbon don't work quite the way you might think. It's best explained with an example.

With the example of Chapter 2, a couple of screenshots ago, suppose we start off on the first page of section 6 (remember — we've defined section 6 to mean the same as Chapter 2). If we click 'Next section', you would be forgiven for thinking we would move from section 6 to section 7. We don't! We move from 'First page header – Section 6' to 'Even page header – Section 6'.

If we carried on hitting 'Next section' we would then get 'Odd page header – section 6'; then 'First page header – section 7', 'Even page header – Section 7' and so on.

I'm trying to explain in writing here, but this would be a good point for you to go, define some headings, and play with the buttons to see how they work.

Which , what, huh?

At first, I found it confusing to work out which setting affected which part of the book. So here's a summary.

We divide the book into sections.

Some things are properties of a section, such as whether we have a different first page header and some setting we'll see in the next tip about page numbers.

We have up to three different header definitions for each section. The next/previous buttons move between these headers and not between sections, despite what the name says.

We can save a whole lot of effort (and risk) by making our header definitions inherit from the previous section.

As for footers, they work the same way as headers.

We're done for this tip. In the next tips we'll be looking a little more at sections and page numbers, but we've got most of it done in the tip you've just read.

This is the latest instalment in a series of formatting tips. Click on the link to see the previous entries: Part1

January 7, 2012

The Reality War: The Pilgrim's Progress meets Terminator

Expect some more mentions over the next few weeks of The Reality War as my first two novels approach publication. The copy editing report for the first book is almost ready. Cover artwork is coming in. I love what artist Andy Bigwood has done, especially the reptilian girl. She's got a name: Kalichee.

Book1: The Slough of Despond

Book2: The Narrow Path

Tips on formatting your print book for Createspace and Lulu. Part1

Yesterday I completed a commission to format a book interior for Createspace, and wanted to share some tips to help you create your own great-looking Createspace books. This isn't a top-to-bottom comprehensive guide, rather I've written down the things that I wished I knew when I took on the commission.

Although these tips will help you format printed books, the self-publishing authors who would find it useful will often also be interested in designing eBooks too. I won't be explaining how to build professional-looking eBooks in this article, but I will point out where eBook design is radically different from print. Certainly if you are self-publishing then it is a great help to think from the beginning about writing your manuscript so that it lends itself safely and easily to being built into a print book or an eBook.

Createspace is one of a number of print-on-demand companies (Lulu is another main player in this market). The idea is that you supply Createspace with a pdf or other file for the book's interior, and do the same for the cover (or use one of their templates). Once you're happy, you tell Createspace to print however many books you want and then wait for then to be delivered. The book will also be listed at places such as amazon.com for customers to purchase and have the book printed and delivered by Amazon without you getting involved at all (except to get paid!)

Simple!

Actually, it's not quite as simple as that to get the formatting looking good. You also need to know some conventions about how to lay out books professionally, because some reviewers will consider your book to be amateurish if you don't.

The book I formatted is called Drift, by author Andrew Cyrus Hudson. Drift is a novel, and I've used standard fiction layout. I used Microsoft Word 2007 on Windows XP, but the concepts should translate easily enough to other desktop publishing and word processing packages, such as Open Office.

Tip#1 Don't start from here! Start formatting as you write your book

You can save yourself a lot of grief by picking the styles you will use and applying them as you write. If you don't use styles in your writing then now's the time to start. Also dividing the book into sections as you go, and setting headers and footers will save a little time too. By the way, this is even more true for eBooks, which have a habit of revealing subtly inconsistent formatting that is difficult or impossible to spot.

Don't worry about locking yourself down to a particular font or size, because you can modify the style definition at a later stage. Concentrate on becoming familiar with a set of styles, and apply them as you go. Microsoft Word has the Style Set concept, which is perfect for this.

Do yourself a favour and invest in a little time to consider how you can use styles. For fiction books, you probably want styles for: title, headings, front matter, first paragraphs of a scene (with zero indent), body text (with first line indent), a 'blank line' style (with spacing above and below — very useful for Smashwords), and centred text. I'd also suggest that where you have an entire paragraph in italics, that you create a style for this too (I have 'italic' versions of my first paragraph and body text styles.

I've produced dozens of books now, and I can say that the two formatting errors that are most likely to sneak up and bite you are: inconsistent formatting from not using styles, and botched attempts at justifying text.

Tip#2 – Plan your layout strategy for your pages

Take a selection of professionally produced physical books off your shelves and have a look at how they're laid out. Then come back to me.

Ready?

If you were looking at adult fiction books then you should have found some variation but a typical approach works like this:

The title at the beginning of the book is on a facing page. In word processors, these are called odd pages. Why? Because the facing pages always have the odd page numbers. Go on, try it. All the books on your shelf will work that way.

If you have Parts in your book (Part1, Part2 etc) then they will be on odd pages, and the chapter heading that follows will also be on an odd page.

This means you will always get a blank page between the odd page with the part heading and the odd page with the chapter heading. Depending on your other page layout choices, you may get other blank pages too.

Blank pages have no header and no footer. They are totally blank. They still count in the page count but the page number is not displayed.

Pages with chapter headings don't have a header. They might have a footer. Many books don't have footers, only a header, and for these books, pages with chapter headings do not display a page number.

Some books always start a chapter on an odd page, others don't. I think that books that don't start chapters on new pages tend to be cheaper, mass market pressings, or those are with shorter chapters. There isn't a hard rule here, and I'm sure some would disagree. If the book is a collection or anthology of short stories, then new stories should definitely start on odd pages. New chapters on odd pages look smarter in my view.

Let's look at some examples from our example book, Drift. Here are a couple of screenshots from the Interior Reviewer, a great tool for inspecting how your book will look.

Start a new part on a facing page

The first example is mostly white space. Not very interesting, you might think, but in book formatting, we want blank pages to really be blank, no headers here. Same with the Part title. Ultimately, the blank page and the lack of headers in this example has come about from the way I defined the sections in Microsoft Word. The blank page was added automatically (because I set section start to odd page, and different first page for the header — you'll learn how to do that later). To some people familiar with books (such as those reviewers you were thinking of sending a copy to) missing off the blank page, or having a header over it looks amateurish. Don't give them a reason to think poorly of your book!

Start the first chapter of a new part on a facing page

In this next screenshot, we've turned the page. There is a blank page added automatically because we want the first chapter of a new part to start on a facing page.

You're possibly thinking at this point that I didn't actually bother with headers at all. Honestly, I did put in a header, and if you turned the page to read on into chapter1, then you would see them.

We'll look in more detail at headers and footers — and their connection to sections — shortly. But first, we need to look at page setup and how to use templates provided by Createspace and the other print-on-demand sites.

Tip#3 — Copy the page setup from the Createspace template INTO your document

Lulu and Createspace have Microsoft Word templates for each trim size (trim size is the page size of your book, for example 6" x 9" is common). If you've already written your manuscript in Word, do you copy into the template or copy the template definition into your manuscript? What if you aren't using Word at all?

My answer to both questions is to examine the page setup for the template and apply to your manuscript. If Microsoft Word is available to you, the alternative is to copy your manuscript into the template chapter by chapter. I don't like the second approach because it looks dangerous (How can you be sure you've copied all the right pages into the right place in the right order? Answer: you can't without a thorough read through.) and because pasting tends to bring across more than you think (such as page setups and styles) and overwrite what was in the template (which defeats its purpose).

I'm going to show you the page setup I used for the Drift manuscript at Createspace. The terms (such as gutters) are standard, so even if you aren't using Word, you should have similar options available to you. If you aren't sure what the terms mean, look at your manual or Google. (Hint: Microsoft Word help is online, so you don't need to use the software to read the manual or see a huge amount of online guidance).

You should be entering all these values, but I've highlighted a few I'm going to talk about.

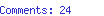

To bring up the 'Page Setup' window in Word 2007, click the little box on the bottom-right of the Page Layout section of the ribbon.

Mirror margins: This is a key setting. It tells Word that the page layout here is for facing (odd-numbered) pages. Whatever you set here will also be used for even-numbered pages, but the margins will be a mirror image. In this example, the margin is set much larger at the inside of the page (the bit that disappears into the middle and is glued to the binding). Microsoft explain this clearly in this online article.

Apply To: Apply the settings to your entire document. Normally the pages will all be the same. The differences will be with headers and footers; we'll come to them later.

Don't forget to set the paper size to match the trim size you selected.

Remember in the last topic, I mentioned that we want certain pages to always appear on an odd-numbered page? For example, when you begin a new part, or a new story in an anthology, you want the title page for the part/ story to be on an odd page. That's what we're telling Word to do by saying Section start: Odd page. When you print the document, or convert to pdf, Word will insert blank pages at that point if it needs to in order to start the new section with an odd page. In Word 2007, you won't see this blank page even in print layout, but it will be created when you print or create the pdf.

In the example I'm working through (Dift by Andrew Cyrus Hudson, a typically formatted fiction book) you will want different headers and footers for odd and even pages (headers are the next topic) and a different first page.

Apply this to the entire document, though you might want to change the section start setting later on. If you have decided you don't want to insist that new chapters start on odd pages, instead of setting Section start to odd page, you should set next page as your default, and put the odd page section starts back into the sections where you need them. (There is a topic coming later about sections and how to set properties for sections)

The Createspace templates are currently here, Lulu's are here. Although it's a little cheeky, I think it is worth looking at both sites for community help, templates, wizards and such like. For example, some (not all!) UK authors will find Lulu to be the compelling choice, but they might find the cover template wizard and interior reviewer on Createspace to be just what they need. In which case they can create a Createspace account, use the Createspace tools, but upload and print the final pdfs to Lulu.

I'll weigh the pros and cons of Lulu and Createspace later on, but one thing worth pointing out is that they are all changing and improving over time. So if it's been a while since you last produced a book, it's worth looking at the other site because their tools, guidance, and pricing might have moved on since you last looked. And if you are a UK Lulu author, it's worth considering that there are rumours that Createspace will begin UK operations.

That's all for this post. In a few days, I will add some more from the following:

Headers and footers

Sections

When to start page numbering

Page numbering and section gotchas

Justifying text – when and how

Dinkus asterisms, and how print and ebooks are different

Font embedding and pdfs

Adding blank pages at the end of the book

Createspace vs. Lulu. Which is best?

Cover art tips

Add a comment if you want to ask anything… or disagree

See you next time.

Tim