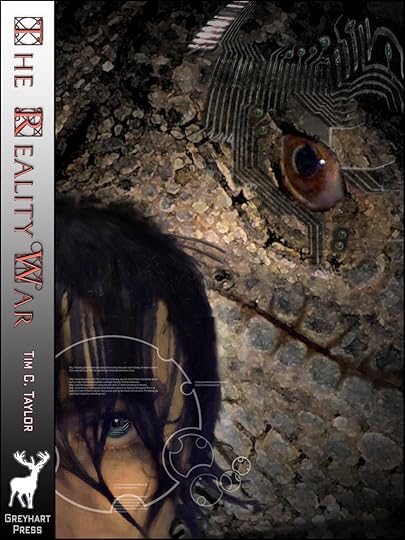

The Pilgrim's Progress and The Reality War: Part 1

John Bunyan

When talking about my science fiction novel series, The reality War, I've sometimes mentioned a connection with John Bunyan and his hugely popular book The Pilgrim's Progress (1678). Several people have asked me to explain more about that connection. Are my books simply a retelling of The Pilgrim's Progress, making them a Christian allegory dressed up in science fictional clothing? Or are they an anti-Christian allegory? There again, perhaps the Bunyan connection is no more than a marketing ploy, a few words crudely bolted onto my story, and just as easily taken away again?

In this post, I'll look at The Pilgrim's Progress and pick out a few common criticisms as a tool to examine it in a little detail. In the following post, I'll show some of the connections between The Reality War series and The Pilgrim's Progress. But first…

The Concise Answer

Book1: The Slough of Despond

How are my books connected to The Pilgrim's Progress? The concise answer is that the thematic idea of a spiritual journey operates at a deep level across my books, and was always present in my mind as I crafted the story. Readers hoping for a faithful retelling of Bunyan's plot will be disappointed, but without The Pilgrim's Progress as my blueprint, I would have written a very different book. So there is a deep thematic link, even though I don't spell out a specifically Christian journey.

There are more literal connections too, both in sharing the same geographical setting (Bunyan used real locations in the Bedford and Elstow area) and in a few specific actions of my characters that I can't explain without giving away spoilers.

Elstow Green and the Moot Hall

The events of my book play out in Bedford and Elstow, the places where Bunyan lived and worked. Key events play out in a row of cottages called Bunyan's Mead. They didn't take that name in the seventeenth century, of course, but the cottages predate Bunyan. In other words, when Bunyan lived in Elstow, he would have walked past those same cottages every day. Then there's a scene in Elstow Green, a real place where I picked conkers with my son last year, and where my wife danced as a girl in the May Day celebrations. It was here in Elstow Green where, as a young man playing a bat-and-ball game called tipcat, that John Bunyan had a vision from God that placed him upon the narrow path of godliness. It was the annual fair at Elstow Green that Bunyan references in The Pilgrim's Progress, coining the term: Vanity Fair. I could go on. I won't, but if you want to see more of Elstow, the Tudor cottages and Elstow Green, there's a collection here.

As for literal references, I have kept them as deep hints because they are not fundamental to the understanding or enjoyment of my novels. After all, time travel novels have a tendency to drift into over-complexity if you let them; tangents that are potentially confusing need to be stamped out. Nonetheless, if you look for the hints, the time-meddler, Greyhart, may have more than a theoretical knowledge of Elstow in the seventeenth century.

A brief history of The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress first edition. I think my cover art is better!

Bunyan's book has been phenomenally successful. That's a term bandied about so frequently that it has lost its impact, but phenomenon is the right word to use. A century after first publication in 1678, Benjamin Franklin wrote of The Pilgrim's Progress in his autobiography, speculating that it had been read more than any other book except the Bible. A Google search for "The pilgrim's progress" returns over 3 million hits.

Bunyan's book describes an allegorical journey of a man (Christian) making his assisted way from the sinful world of Man (The City of Destruction) through many obstacles and meeting many characters along the way (mostly those who would lead him off the narrow path, but genuine help is there for those who look for it) until eventually he reaches heaven (the Celestial City — although some interpret the Celestial City more broadly, encompassing those still alive but qualified for heaven).

To modern readers, the allegory may appear crude, but in Bunyan's time, modern readers did not exist. I think Bunyan would have thought of his book as a linked series of parables , a technique for telling a story with a moral that would be very familiar from the New Testament. Bunyan was a Puritan preacher, and I imagine he thought of each chapter as a sermon. Puritanism was an English manifestation of Protestantism that fought successfully for influence over the development not only of modern England, but of America too. You see this Puritanism at work in the text, where Bunyan sets out a path to salvation but only for those who follow the right kind of Christianity. As a Puritan, and himself uneducated, Bunyan was aiming his book at the common man (and, as we'll see — possibly after some prompting — at the common woman too) and not at the educated elite of the land (those who imprisoned him more than once). The apparent crudeness of the allegory may have been a factor in its popularity, not only because it was understandable by simple uneducated folk, but because its lack of (apparent) artifice was popular with educated Protestants who championed the simplicity and directness as virtues.

If at times, the allegory is heavy-handed then that is a charge I dismiss, both because that is a stylistic choice, and because judged within the context of its time and its purpose (ultimately, Bunyan wrote his book in order to save souls) the book succeeded brilliantly. Sophisticated readers have always been quick to condemn populist literature. In recent times, JK Rowling has been rubbished for her crude Harry Potter series, as has Dan Brown with his The Da Vinci Code. Some of that criticism might be well-founded, but in the end it misses the point. Harry Potter and Da Vinci Code were designed to be stories that regular people would enjoy. Bunyan succeeded then as JK Rowling and Dan Brown succeed today.

One thing I've found in my experience with publishing eBooks is that sometimes people are quick to criticise a book for faults they assume it has, without troubling themselves to actually read it. And so it is with The Pilgrim's Progress. When I first read the book, I too thought some of the allegory was crude. I read it in Bedford Central Library, in the local history section. As Bunyan is by far the most famous individual connected with Bedford, I was surrounded by dozens of editions of The Pilgrim's Progress and books about Bunyan and his works. Reading through some works about The Pilgrim's Progress reveals a surprising truth for a work supposedly so crude: learned people over the past four centuries have tried to decode the book's allegory and arrived at different answers, and many of the interpretations are intricate and subtle. For me, that's the killer. An allegory that is open to interpretation cannot be so crude, can it?

Mansplain your way out of that!

Another criticism is that there is a gaping hole in Bunyan's thinking behind The Pilgrim's Progress. Considering the book as a series of parables/sermons rather than a single narrative thread might help to understand Bunyan, but no amount of mansplaining by me or by Bunyan himself really gets him out of this one.

Consider:

In The Pilgrim's Progress, the hero, Christian, hears about the City of Destruction (code for: realises his immortal soul is in peril unless he finds God). He is so terrified that he bids farewell to his wife and children and starts off on the tricky journey that eventually leads to his soul in heaven. He does try to persuade them to come, and does occasionally bemoan their absence on his journey, but there is never any question of him turning back for them.

Mr Great-heart, aid to Christiana

Let's back up a moment. Christian is a father and a husband. In Bunyan's day, that means a heavy responsibility as the spiritual, legal, and financial head of his household. His wife and children rely on him. But Christian is so intent on saving his soul, that he abandons them.Perhaps surprisingly, the accusation that Bunyan had offered no spiritual hope for women in his book was made immediately upon publication. We writers sometimes talk of 'fridge moments': when someone points out a gaping hole in our stories that is so unforgiveable, our only recourse is to repeatedly bang our head against the fridge. If Bunyan had a fridge, I wonder whether it would have had a few head-sized dents.

I honestly don't know. If anyone does know about Bunyan's reaction to this criticism, I'd love to hear about it. Having personal experience with writing a series of time travel novels with a theme of spiritual journey, I know that books can quickly get out of hand in terms of complexity, and sometimes need leading back into a simpler shape to be enjoyed by the reader. That means leaving things out. Perhaps Bunyan deliberately left out the family in order to concentrate onto personal journey that, in his view, everyone must complete on their own. Or maybe I'm just mansplaining J

Bunyan acknowledged this problem and wrote a sequel, where Christian's wife, Christiana, and children set off on their own journey of spiritual salvation. True to the times he was writing in, Bunyan does not allow Christiana to journey without a chaste male mentor and guardian to assist her. This role is provided by Mr Great-heart. You might see a similarity with the name Greyhart. This is no coincidence, but to explain more would be a spoiler.

To journey unto death

Children's author of His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman has written of his horror at much stories of Christian allegory: The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis. In the final Narnian book, The Last Battle, they fight their climactic battle and meet the Christ-figure, Aslan, once again. I remember reading this book in my early teens and thoroughly enjoying it. Pullman's distaste is that in order to be propelled into their final adventure, the human children must first die in this mortal world.

When I first read The Last Battle, I understood a lot of this but was too caught up in the excitement to pay much attention. Looking back now that I'm a father, I also feel uncomfortable with a children's story that could be seen as championing death as the gateway to the best part of your existence.

Whether this is a telling criticism depends upon the depth of your Christian belief (if any). To Lewis and Bunyan, whose belief was absolute, uncomfortable though their belief about heaven and hell might be, it was the ultimate truth and had to be addressed.

The Pilgrim's Progress is no different. Again, treating the book as a single narrative thread, rather than a collection of sermons, may exaggerate this, but the main character's ultimate objective is to die having overcome his obstacles along his journey. Only then can he truly finish his story in the Celestial City.

Wrap-up

So that's your lot: probably more than you ever wanted to know about John Bunyan and The Pilgrim's Progress… unless you're really into Christian religious texts, in which case it was not nearly enough and probably misguided because I am not myself religious.

Now that I've shown a little bit of The Pilgrim's Progress, next time I'll compare it to The Reality War.