Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 15

September 12, 2021

Travers McLeod’s response to George Megalogenis’ Quarterly Essay, Exit Strategy: Politics After the Pandemic

Published in The Quarterly Essay 83, September 2021

Reading Exit Strategy as most of Australia went back into lockdown with one of the world’s worst vaccination rates made me wonder whether the title was an oxymoron.

When historians examine Australia’s response to COVID-19, the absence of a clear strategy to steer Australia beyond a pandemic into a brighter future may well be the most mystifying part of the whole episode. Our inability to plan and implement a response to a known systemic risk could be one of the biggest own goals in our nation’s history. If repeated on climate change, we are doomed to fail.

None of this discounts George Megalogenis’s essay, which offers a dose of history on how Australia has tackled systemic shocks, the latest of which is COVID-19. His story of the distinctive values and culture of Australia’s public services and the widespread acceptance that they should be able to offer frank professional advice without fear of losing their jobs provided a ray of light in an otherwise grim time, as did his snapshot of the new lease of life in Joe Biden’s America, where strengthened social infrastructure and a $450 billion investment in early childhood development are central tenets of the response.

Australian policymakers have known about the devastating regularity of pandemics for some time, and they were warned about the risk of coronaviruses specifically nearly a decade ago. A Senate Estimates hearing in federal parliament way back in June 2013 was told the possibility of a “novel coronavirus” was “very scary.” Among the participants in that exchange was Jane Halton, then secretary of the Department of Health, who was appointed to the National COVID-19 Coordination Commission (NCCC) in March 2020 and was a key adviser as Australia explored suitable vaccines.

When the prime minister established the NCCC, he said it would “coordinate advice to the Australian government on actions to anticipate and mitigate the economic and social effects of the global coronavirus pandemic.” This was, he said, “about mobilising a whole-of-society and whole-of-economy effort.” The NCCC sounded like a “red team” for COVID-19, and it should have been, yet by 3 May 2021 its work had concluded. “We have moved past the emergency phase of the COVID-19 response and are now on the path of economic recovery,” said the prime minister. “Australia’s strong health and economic circumstances and our strong outlook make it the right time for the Board to conclude its work.” With Australia then at the bottom of global vaccination rates, and the Delta strain having just been used to justify a ban on Australians returning from India, it beggars belief the NCCC was told to down tools early. One wonders what it actually did, and whether it offered up anything other than smoke and mirrors. Whatever the NCCC spent time on, it does not appear to have war-gamed different strategies on quarantine hubs or vaccination rollouts, or to have tested various tactics to keep Australia one step ahead of the virus.

The grim short story of COVID for Australia is that we were caught napping at the start and have been reactive throughout. While some of our reactions have been inspired, overall we have lacked the courage and creativity to use the crisis to imagine a better future for Australians and for our region. The initial flurry of national collaboration has been replaced by a fractured Federation. According to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Australia now has some of the most stringent restrictions among OECD countries. That is a predictable consequence of sticking with last year’s strategy, not chasing and securing multiple vaccines, being too slow to add new technologies to our arsenal, like rapid lateral flow tests, and not preparing effectively for the inevitable future waves and different strains.

Megalogenis is spot-on about Australians placing their faith in government being the story of the pandemic. I am willing to believe the desire Australians have for more active government was growing before COVID-19. Two years ago, in the Quarterly Essay Australia Fair, Rebecca Huntley wrote that Australia is a nation of democrats. The Centre for Policy Development’s research on public attitudes reinforced this, revealing that, as Australians, we share a unique resolve to make democracy work, solve big problems and improve the lives of others. The 2019 federal election did not disprove Huntley’s thesis. The twin crises since, the bushfires and pandemic, have put it firmly back in the frame. When CPD asked Australians in June 2020 what the main purpose of their democracy is, the answer now three times more popular than any other was ensuring all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable. This answer was chosen by 45 per cent of respondents, up from 36 per cent in 2018, far ahead of other answers, such as ensuring people are free to decide how to live (15 per cent) or electing representatives to make decisions (13 per cent).

The other key takeaway from this attitudes research was how voters across the political spectrum are at the end of their tether with contracting out services. On this, Australians are united. Ninety per cent now think it is important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver services directly, instead of paying others to do it. This is up from 75 per cent in 2018. In a sign of the times, Coalition voters are now the strongest supporters of rebuilding an active role for government in service delivery. The failure of private contractors to roll-out COVID-19 vaccines efficiently will only reinforce this view. Let’s not kid ourselves: when lives are on the line, you want someone to take responsibility, not outsource it.

Megalogenis nails this issue, although I wish he had given us more on the central question he poses: can Australia restore faith in good government? His essay dares to dream that Australia can adapt its model of governing and delivering services “to the new consensus for a more active government” and “reconceive the political economy of the nation.” I agree that the answer lies in reconnecting with communities, just as Lynelle Briggs found in the aged-care royal commission, and that one part of the answer is a more effective approach by the Commonwealth to partnering with (and funding) state and local governments to deliver services in communities. But I want to suggest the challenge is more profound, for at least two reasons.

First, the how is not for the faint-hearted. As Megalogenis writes, “The gaps in the safety net which the coronavirus exploited will become poverty traps in recovery if the government continues to defer to the market.” A new approach requires a reorganisation of government and a commitment to regional and community deals involving levels of government alongside business and the community. That’s very difficult with anaemic public-sector capability and depleted memory at the national level, especially in social policy. Even if it prefers to fund than to deliver, the Commonwealth will need, and the community will expect, more feet on the ground. Digital delivery helps but is no substitute for interpersonal relationships and knowing what it takes to run things well at neighbourhood level, whether this is in early childhood development, aged care, disability or employment services. Each of these service systems faces acute challenges. Take employment as one example. As of 30 June 2021, there were 1,013,452 Australians on the employment services case load. Around three-quarters have been there for over twelve months. More than a third have been there for more than two years. We were asleep at the wheel.

Second, this century demands a richer understanding of what a sustainable economy looks like over the long term. Unless we change tack, it will be impossible to disentangle Australia’s strategy to exit the pandemic from our future approaches to care, climate change, and growth. In each, we see danger signs of the old model: reactive, not proactive, policy development that is based on events, not on evidence and foresight; the government not valuing or nurturing work in the “caring and brain economies” for Australians young and old; and a fossilised approach to boosting economic and social participation in communities in desperate need of new energy and fresh horizons.

Since Megalogenis wrote his essay, the federal government has published its 5-yearly Intergenerational Report, with rosy projections for productivity growth. But at the same time, we have seen a drain of international students and skilled migrants, and a stubborn lack of national planning for carbon transition. Optimistic forecasts are no substitute for an exit strategy.

This future has caught up with us. It demands that Australia change now, or be steamrolled by events. In the run up to a federal election, the prime minister and opposition leader need to answer the questions Megalogenis poses. Otherwise, to use a word deployed by the prime minister during the current lockdowns, we will “squander” the natural advantages and opportunities already open to Australia and be on a road from which there is no exit.

Travers McLeod

The post Travers McLeod’s response to George Megalogenis’ Quarterly Essay, Exit Strategy: Politics After the Pandemic appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

September 7, 2021

Andrew Hudson & Dewi Fortuna Anwar: Time to strengthen Australia-Indonesia partnership

Published in The Jakarta Post on September 8 2021

On Thursday, the Foreign and Defence Ministers from Indonesia and Australia are due to meet in Jakarta for vital talks. The stakes are high. No Australian minister has visited Indonesia since the pandemic began, while ministers have visited Jakarta in that time from many other nations.

As an Australian and Indonesian, we believe our governments should grasp the opportunity of this rare in-person meeting to accelerate a new era in Australian-Indonesian relations. Our two countries have elevated the bilateral relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in July 2020, reflecting the importance of our economic and strategic relationship. The time is right to invest more into the relationship so that the two countries can nurture democracy together, much like former Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa has suggested, and help the region to navigate growing superpower rivalry between the US and China in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia will be Australia’s closest and arguably most important bilateral relationship over the next 30 years, by which time Indonesia is projected to be the world’s 4th largest economy. Indonesia is already a global leader, due to be Chair of the G20 next year and the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2023.

Here are some priorities we hope the governments will agree in their talks.

First, Indonesia is suffering enormously from COVID-19. As others have argued, Australia should considerably expand its Indonesian Covid-19 Development Response Plan to help Indonesia’s recovery. More broadly, Australia should work closely with Indonesia to build regional resilience on other challenges that loom large over the next 30 years, whether it be decarbonisation, shared prosperity, security or human displacement. All are linked — the less distance between the approaches taken by our countries the better.

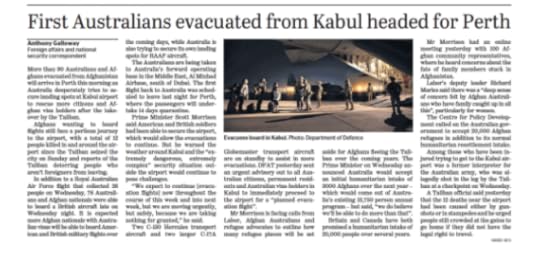

We have watched with horror at the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding in Afghanistan. Of great concern to both Australia and Indonesia should be large-scale displacement of Afghans in the coming weeks and months. Australia’s role in the war in Afghanistan and subsequent Allied occupation elevates the duty Australia owes to those now fearing persecution. The Centre for Policy Development has called for Australia to resettle 20,000 Afghan refugees, in addition to its normal humanitarian resettlement intake. Indonesia has many thousands of Afghan refugees. Given the very limited number of Afghan refugees Australia was able to evacuate form Kabul, one way Australia could help its neighbour, and fulfil its pledge to take Afghan refugees, would be to offer resettlement to some of them currently in Indonesia. These refugees have been stuck in limbo and are increasingly desperate.

Australia and Indonesia should also be worried about the possible terrorist resurgence in the region given the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. Indonesian police recently arrested around 50 suspected members of different local terrorist groups affiliated with Al-Qaedah or ISIS, amid reports they are consolidating in response to the Taliban victory. Al-Qaedah affiliated Jamaah Islamiyah members trained in Afghanistan were infamously responsible for Indonesia’s worst terrorist attack in Bali in 2002 that killed 88 Australians and 38 Indonesians. Indonesia and Australia must work together to root out radicalisation and terrorism in the region, to prevent future terrorist attacks targeting our nations.

Sadly, Afghanistan is not the only crisis in our region forcing huge numbers of people to flee their homes. The continued post-coup crackdown in Myanmar and ongoing persecution of Rohingya are also causing mass displacement. 2020 was the deadliest year on record for refugee journeys in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal. We hope Australia and Indonesia will agree a coordinated approach to apply more pressure both to the Myanmar junta and ASEAN to implement the agreed 5-point consensus for Myanmar. A political agreement is badly needed in Myanmar to stop the violence — greater advocacy and coordination from Indonesia and Australia can help to achieve that.

Our organisations co-convene the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM) with colleagues in Malaysia and Thailand. We have long warned the combination of events in Myanmar and Afghanistan, the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change risk a dire displacement crisis in the Indo-Pacific. Australia and Indonesia co-chair the main inter-governmental body dealing with forced migration – the Bali Process. We hope, at their meeting this week, the co-chairs will agree an urgent date for a Ministerial meeting of the Bali Process to discuss these crises – the last Ministerial meeting was in 2018. The 20th anniversary of the Bali Process next year is a big opportunity for the co-chairs to propose reforms to make the institution more effective and impactful in the wake of COVID.

Australia and Indonesia will need to have each other’s backs in the decades ahead. Now is the time to strengthen our partnership and work together on the unprecedented challenges facing the region.

Andrew Hudson is International Director at the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) in Australia. Dewi Fortuna Anwar is a former Deputy Secretary for Political Affairs to the Vice President of Indonesia and incoming board member of CPD.

The post Andrew Hudson & Dewi Fortuna Anwar: Time to strengthen Australia-Indonesia partnership appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

September 6, 2021

Leslie Loble, Travers McLeod & Jen Jackson: America has a big-picture vision for its children, so why don’t we?

Published in The Age on September 1, 2021

Amid fears about the long-term impact of COVID on kids, it’s worth reflecting on the bigger picture for children in Australia – the story we have much greater control over.

Nelson Mandela said you can judge a society by how it treats children. This wasn’t a platitude but a prescription for good government. It’s a script followed by President Joe Biden, who has made children central to his vision for America and an essential part of his strategy to compete with China.

A large part of Biden’s budget that advanced in Congress last week is the American Families Plan, which includes a $US450 billion investment in American children in the crucial early years.

This includes $200 billion for preschool for all three- and four-year-olds, and $225 billion so that low and middle-income families spend no more than 7 per cent of their disposable income on childcare costs and so early childhood services can improve quality and wages. The remaining $25 billion will create essential infrastructure to deliver on this vision.

Biden introduced the package at his first joint sitting of Congress in April. “To win that competition [with China] for the future”, he said, requires “a once-in-a-generation investment in our families and our children”.

The President cited studies showing that “adding two years of universal high-quality preschool for every three-year-old and four-year-old, no matter what background” enables them to “compete all the way through 12 years” and “going on beyond graduation”. He said the future will belong to countries who invest in early learning.

So where is Australia with children and this competition for the future? The recent federal budget and intergenerational report provide partial answers.

The budget read a little like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and had some big treats. Guaranteeing preschool funding for four-year-olds is a big reform long overdue and one for which the Commonwealth deserves credit. But it is a long way from the American plan to deliver two years of preschool nationwide.

Similarly, the $1.7 billion investment in the childcare subsidy is a welcome announcement for families coping with the ever-increasing costs of early childhood education and care. Yet this story was framed as a treat for working mums, not as an investment in children with a double dividend for parents.

And there is no goal for how much families should spend – well over a third of Australian families still pay more than 7 per cent of disposable income on childcare.

The intergenerational report read more like The Gruffalo. Reams of pages on the growing dependency ratio, the (un)sustainability of essential services and a half-baked section on climate change would make any child feel let down. If children look hard, they will find themselves mentioned 48 times, but in the context of fertility rates, female workforce participation and the childcare subsidy. “Oh, the places you’ll go!” said absolutely no parent after putting down that bedtime story.

The COVID chaos makes it even more important to get the story straight about what Australia guarantees for its young children and their families, and how our early childhood development system can be the world’s best.

This story should start with what we know is a no-brainer: the importance of early learning for brain development. But it also needs to consider the interaction of critical services for children and families, often supported by different levels of government.

Our maternal and child health systems and early learning systems barely talk to each other. Our parental leave system bakes in inequity between women and men. Our focus on ‘jobs’ overlooks the early childhood workforce who shape our children’s fertile young brains.

Families are left with a fragmented system that compounds stress and confusion.

Governments have a responsibility to consider how these services are best funded, staffed and delivered, and to understand the cracks that children and families can fall through. They can agree on a shared vision and mobilise many contributors to turn the vision into reality.

If we want a more exciting story for Australian children, the forthcoming Preschool Reform Funding Agreement – a $2 billion national reform commitment to strengthen the delivery of preschool and better prepare children to start school – is a big opportunity to accelerate an Australian early childhood reform agenda.

To do so, the agreement has to be written with much more than a single year of learning for four-year-olds in mind. Preschool is important, but only as part of a connected system that supports children and their families from the time a child is born to when they start school.

Now is the time to make our early childhood system the backbone of Australia’s social and economic wellbeing. With investment and vision, we can make Australia the best place in the world to be a child, and to raise one. And we need to be to punch above our weight and compete this century.

The post Leslie Loble, Travers McLeod & Jen Jackson: America has a big-picture vision for its children, so why don’t we? appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 22, 2021

CPD is hiring a Communications Director

CPD is recruiting a Communications Director (part time). This is a new key leadership role for an innovative and collaborative individual with experience in media or government relations to build the profile of our work and organisation.

Read the position description below for more information:

The post CPD is hiring a Communications Director appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 19, 2021

Australia should take 20,000 Afghan Refugees

Thursday 19 August 2021

CPD is calling on the the Australian government to accept 20,000 Afghan refugees in addition to its normal humanitarian resettlement intake. Australia cannot escape its responsibilities to Afghanistan and the Afghan diaspora in Australian communities.

Read our full statement here:Coverage of our statement in the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age

Article by Anthony Galloway

The post Australia should take 20,000 Afghan Refugees appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 9, 2021

CPD appears at the Senate inquiry into the current capability of the Australian Public Service

On Friday 6 August 2021, CPD’s CEO Travers McLeod, CPD Chairperson Terry Moran AC and Senior Policy Advisor Frances Kitt appeared at the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee’s inquiry into the current capability of the Australian Public Service. Travers, Terry and Frances highlighted the cultural, philosophical, managerial and situational problems with current APS capability. They drew upon CPD’s extensive work in public service capability, including the impact of the efficiency dividend, the effectiveness of big service delivery systems, research on Australian attitudes to democracy and to government, and place-based approaches to service delivery.

Watch CPD at the inquiry here:

CPD’s submission to the InquiryCPD’s opening statement

CPD’s submission to the InquiryCPD’s opening statement

Other related links:

Web page for the inquiry into the current capability of the Australian Public ServiceFull video of CPD before the Finance and Public Administration References CommitteeTranscript of the inquiryThe Mandarin reports on Terry Moran’s appearance at the InquiryTravers McLeod on ABC Radio National’s four part series on APS capabilityThe post CPD appears at the Senate inquiry into the current capability of the Australian Public Service appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 28, 2021

CPD appears at the inquiry into the prudential regulation of investment in Australia’s export industries

On Wednesday 28 July 2021, CPD’s CEO Travers McLeod and Sustainable Economy Program Director Toby Phillips appeared at the inquiry into the prudential regulation of investment in Australia’s export industries. Travers and Toby drew upon CPD’s work on directors’ duties and climate change and the Climate & Recovery Initiative to highlight that structural change driven by climate impacts and decarbonisation will create major challenges, risks and opportunities for many Australian businesses and regions. They also highlighted that risks from a changing climate and changing global demand for carbon-intensive goods are material to the interests of many companies and investors, who have clear duties to consider the financial impacts of climate change.

Watch Travers McLeod’s opening statement here:

https://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Opening-statement-Pitt-Inquiry-low-res-2.mp4

CPD’s submission to the inquiry CPD’s opening statement

CPD’s submission to the inquiry CPD’s opening statement

Other related links:

Web page for the inquiry into the prudential regulation of investment in Australia’s export industries Full video of CPD before the joint standing committee Transcript of the inquiryThe Climate & Recovery InitiativeDirectors’ Duties and Climate RisksThe post CPD appears at the inquiry into the prudential regulation of investment in Australia’s export industries appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 18, 2021

New Materials: Early Childhood Initiative Evidence Pack 1

CPD’s Early Childhood Development (ECD) Initiative is pleased to release its first evidence pack: ‘Building the Case for Reform’.

The evidence pack has been adapted from materials prepared by the CPD team for the first two meetings of the ECD Council. This initial pack focuses on early childhood education and care (ECEC) as a key part of the broader ECD system. The pack outlines the opportunity to reposition early childhood development, and particularly ECEC, as a major driver of economic and social outcomes for all Australians, making the case for a ‘guarantee’ to all Australian children and families.

While this evidence pack incorporates ECD Council feedback, it should not be considered representative of an agreed view of the Council, or as representing the views of individual participants or their organisations.

Click here to view the evidence pack:

Links and Related Reading:

Introducing CPD’s Early Childhood Development InitiativeEffective Government ProgramJen Jackson, Early childhood educators are leaving in droves. Here are 3 ways to keep them, and attract more, The Conversation, January 2021The post New Materials: Early Childhood Initiative Evidence Pack 1 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 12, 2021

Virtual Workshop on Case Management in the Context of International Migration | 31 May 2021

In May 2021 the Secretariat of the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM) was pleased to co-convene a virtual workshop with the International Detention Coalition (IDC), focused on case management approaches in the context of international migration.

Materials

Event Summary

Materials

Event Summary

The ADFM Secretariat is pleased to continue to build the Regional Peer-Learning Platform and Program of Learning and Action on Alternatives to Detention of Children in collaboration with the International Detention Coalition.

The latest event in the Regional Peer Learning Platform was a virtual workshop held on 31 May 2021. Around 40 participants came from operational and policy agencies in governments in Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Thailand, as well as national and international civil society groups.

Case management has been identified as a topic of significant interest by Regional Platform participants at past sessions. The Virtual Workshop provided space for practical discussion about what makes case management approaches effective, what services are required, and the benefits of using case management approaches in a migration context.

Participants discussed the benefits of using case management approaches in the context of alternatives to detention, and shared some challenges they have faced in their implementation in different countries. The workshop follows on from a successful in person roundtable in November 2019 in Thailand, and a subsequent virtual roundtable on mainstreaming child protection, held in December 2020.

Despite the challenges posed by COVID-19, we have been pleased to find strong agreement on the utility of the platform and a commitment to continuing to build it together.

Key documents and related reading

Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration

Regional Roundtable on Alternatives to Child Detention | 21-22 Nov 2019 | Bangkok

The post Virtual Workshop on Case Management in the Context of International Migration | 31 May 2021 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Regional Peer-Learning Platform and Program of Learning and Action on Alternatives to Child Detention

CPD, as part of the Secretariat of the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM), is pleased to co-convene a Regional Peer-Learning Platform and Program of Learning and Action on Alternative Care Arrangements for Children in the Context of International Migration in the Asia Pacific with colleagues at the International Detention Coalition (IDC).

The Peer-Learning Platform was first proposed at the seventh meeting of the ADFM in Bangkok in November 2018, where participants identified a regional grouping on this issue as being beneficial to advancing practical progress towards alternatives to detention in the region.

Since then a number of events have been convened on the topic. Participants are drawn from policy and implementing agencies within the governments of Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Thailand, as well as civil society and international organisations.

1: Regional Roundtable on Alternatives to Child Detention

Bangkok |21-22 Nov 2019

The first meeting took place in person in Bangkok, Thailand on 21-22 November, and comprised a full day roundtable, preceded by a day of site visits, coordinated by the Thai Department of Children and Youth, Host International and UNICEF Thailand.

There was agreement at this event about the ongoing utility of this platform, and participants made a range of suggestions for ways to continue the work, including further roundtables, bilateral study visits, information exchanges and capacity building.

More information about the roundtable can be found here.

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

2: Roundtable on Mainstreaming Child Protection in the Context of International Migration

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

2: Roundtable on Mainstreaming Child Protection in the Context of International MigrationVirtual | 14 December 2020

The next meeting took place virtually due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. With travel restrictions in place, participants from the 2019 roundtable expressed an interest in re-convening online to continue the peer-learning platform.

Thus the ADFM Secretariat and IDC convened a virtual roundtable in December 2020, which focused on Australia’s experience mainstreaming child protection and child safeguarding and how that applies to children in the context of international migration.

More information about the roundtable can be found here.

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

3: Workshop on Case Management

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

3: Workshop on Case ManagementVirtual | 31 May 2021

The latest event in the Platform was a virtual workshop held on 31 May 2021. The session focused on case management approaches using examples from two civil society groups in Malaysia to begin the discussion. Participants discussed the benefits of using case management approaches in the context of alternatives to detention, and shared some challenges they have faced in their implementation.

More information about the roundtable can be found here.

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

Agenda and Participant List

Event Summary

The ADFM Secretariat is grateful to the International Detention Coalition (IDC) for co-convening this Platform with us, to all participants for their active engagement in the process and to the Australian Department of Home Affairs and New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade for their support.

For more information about the Peer Learning platform please contact the ADFM Secretariat on adfm@cpd.org.au.

The post Regional Peer-Learning Platform and Program of Learning and Action on Alternatives to Child Detention appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Centre for Policy Development's Blog

- Centre for Policy Development's profile

- 1 follower