Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 19

September 27, 2020

Climate & Recovery Initiative

CPD in partnership with ClimateWorks, Ai Group, ACTU and Pollination

The Climate and Recovery Initiative brings together prominent leaders from government, business and civil society to identify the best ideas for aligning Australia’s economic recovery with a transition towards a net zero emissions economy, and to get them into the right hands.

The Initiative is coordinated by the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) and ClimateWorks Australia, with a steering group that includes the Australian Industry Group (Ai Group), the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), and Pollination.

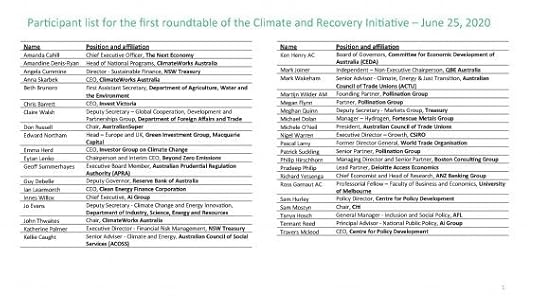

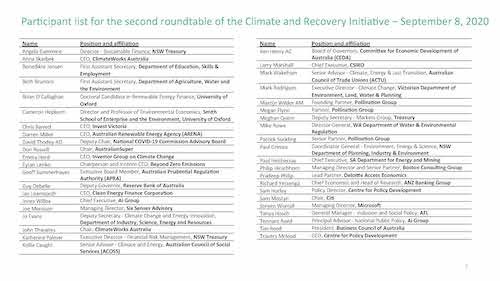

Working together since May 2020, the group has hosted two large stakeholder roundtables, convening senior officials from the Commonwealth and state governments alongside leaders from industry, unions, community organisations, think tanks and academia. Participants include representatives from the Business Council of Australia, AiGroup, ACTU, the Investor Group on Climate Change, the Australian Council of Social Services, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA).

The Initiative was formed in recognition that Australia faces two generation-defining challenges: recovering from the coronavirus pandemic and responding to climate change. These challenges are intertwined. Investments in climate resilience and net zero ambition today can turbocharge Australia’s recovery and position the country for stronger and more sustainable economic growth in the years ahead. The group is focused on both job-creating stimulus opportunities and broader policy changes that could sustain national collaboration on systemic risks like climate change.

At the first roundtable on 25 June 2020, participants shared frank insights and discussed opportunities to better align Australia’s economic recovery with climate and transition priorities. The discussion centred on three priority areas:

Identifying crisis response measures that can support jobs and growth now while aligning with a transition to a low emissions economy.

Entrenching ‘net zero’ in the wider policy agenda, making climate risk and resilience central to economic policymaking while planning the energy transition to protect the livelihoods of workers and communities.

Building new processes and models for more coordinated and ambitious climate responses, ensuring a long-term legacy from the current crisis.

The agenda and participant list from the first roundtable are available below, along with a framing paper prepared for the discussion.

At the second roundtable on 8 September 2020, participants discussed policy proposals including new processes on climate risk and resilience to inform the National Cabinet and an Australian Clean Technology Market-Creation Co-Investment Partnership. The proposals received encouraging support from a range of participants. Further detail on these proposals is available below, along with the agenda and participant list from the second roundtable.

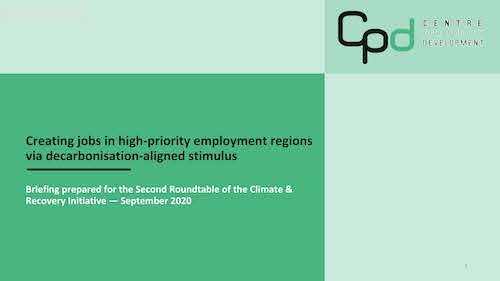

Two research papers developed to inform the second roundtable are also available below. The first identifies opportunities to create decarbonisation-aligned jobs in employment regions that have been doubly disadvantaged by long-term high unemployment and worse-than-average impacts from COVID-19. The second analyses global green technology patent activity, finding that Australia performs well among global peers in green innovation.

The Climate and Recovery Initiative will continue for the remainder of 2020 and into 2021, with key windows including the formation of the 2021-22 Federal Budget and the lead up to COP26 in November 2021.

Please note that the attached documents were prepared by the roundtable organisers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the individuals or organisations present at the roundtable.

Materials from Roundtable One, 25 June 2020

Roundtable one pack including agenda and framing paper

Roundtable one participant list

Roundtable one framing paper

Roundtable One:

Pack (agenda and framing paper)

Roundtable One:

Participant List

Roundtable One:

Framing Paper

Materials from Roundtable Two, 8 September 2020

Roundtable two pack including agenda and summary of proposals

Roundtable two participant list

Proposal: New process on climate risk and resilience to inform the National Cabinet

Proposal: Australian Clean Technology Market-Creation Co-Investment Partnership

Analysis: Creating jobs in high-priority employment regions via decarbonisation-aligned stimulus

Analysis: Measuring green innovation in Australia

Briefing: COVID-19 fiscal recovery pathways

Roundtable Two:

Pack (agenda and summary of proposals)

Roundtable Two:

Participant List

Proposal: Australian Clean Technology Market-Creation Co-Investment Partnership

Proposal: New process on climate risk and resilience to inform the National Cabinet

Analysis: Creating jobs in high-priority employment regions via decarbonisation-aligned stimulus

Analysis: Measuring green innovation in Australia

COVID-19 fiscal recovery pathways

Proposals for more coordinated and effective climate responses

Participants at the second roundtable discussed two proposed processes on climate risk and resilience that could support better coordination between state and federal governments and the private sector in the new federation structures to replace the Council of Australian Governments. The first model would incorporate an explicit focus on climate risk and resilience as part of the Council of Federal Financial Relations, which reports to the National Cabinet. This would help Treasurers and officials address climate risks and the need to build climate resilience as part of the broader economy policy agenda.

The second would establish a new forum or taskforce on climate risk and resilience, which would include senior government officials, financial regulators, and leaders from business and civil society. The taskforce would advise the government on opportunities to enable sustainable jobs, growth and investment in a challenging natural environment, informed by the implications of climate change for financial stability, risk management and corporate governance.

Participants also discussed a proposed Australian Clean Technology Market-Creation Co-Investment Partnership (CIP). The CIP is a model for providing financing to scale up supply chain responses in clean technology markets across Australia in order to enable decarbonisation across all sectors of the economy. It could be implemented as a partnership between the Commonwealth Government and the state and territory governments, whereby state and territory government program investment, traditionally through the form of grants, could be better coordinated to leverage co-financing investment contributions from the Australian Government and attract private investment.

Investment opportunities would be identified using a multi-sector goal-oriented approach, using ‘reverse auction’ style competitive rounds. This model would collectively leverage a greater amount of private sector capital, delivering bigger economic and employment impacts, lowering economy-wide emissions and leading to greater resilience of the Australian economy.

Support for greater alignment of Australia’s recovery with climate priorities

CPD CEO Travers McLeod said that the Initiative has highlighted broad support for greater alignment of Australia’s recovery and climate priorities and the desire for a more ambitious, coordinated response.

“The seniority and breadth of Climate and Recovery Initiative participants shows there is widespread support for a smart recovery that aligns job creation today with a long-term vision for a thriving, zero carbon Australia. This can create lasting benefits across all Australian regions, including those hardest hit by COVID-19.”

“Like COVID-19, climate change poses risks to every sector of our economy – but it also creates major opportunities. There is a need for a more coordinated response across state and federal governments and in the private and community sectors. The federation reforms under the new National Cabinet should ensure that governments are working together to address climate risks and resilience and building partnerships with industry and communities.”

Travers McLeod

ClimateWorks Australia CEO Anna Skarbek said that aligning Australia’s economic recovery with a trajectory to net zero emissions will require ambition and cross-sector collaboration, which is exactly what the Initiative is about.

“Australia can achieve net zero emissions by 2050. To do so, we must invest in decarbonisation across all sectors of the economy and in all states and territories. Smart investments today can lay the foundation for long-term growth and prosperity.”

“Better coordination of efforts between the Commonwealth, the states and the private sector can drive large-scale investment, job creation and economic growth while lowering economy-wide emissions.”

Anna Skarbek

Pollination Group Senior Partner Patrick Suckling said that investors and the private sector are becoming more aware of the role of capital in building a more resilient and net-zero emissions economy.

“As corporates are increasingly factoring climate risk and opportunity into their operations as core business, so should governments as core economic management. Similarly, shifting the billions required to transition to a net zero emissions, more climate resilient economy requires public and private capital to work together and in new and better ways. It was encouraging to see consensus among the Climate and Recovery Initiative participants on these two fundamental points, to hear agreement on possible pathways forward on both and to feel the strong unanimity that it is not a choice between emissions reductions and growth and jobs. Rather the two can be mutually reinforcing – we all need to make sure they are.”

Patrick Suckling

Australian Industry Group CEO Innes Willox said coordinated State and Federal efforts will support stronger growth and ensure clean economy finance initiatives have greater impact.

“Australia’s growth trend was weak even before the massive slug of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the escalating costs of climate change have become increasingly obvious. Steps to protect our economy and society by managing and reducing climate risks will support stronger growth for decades to come. Many steps will also have an immediate benefit in restoring growth and employment.”

“Keeping climate risks on the radar of economic policy makers makes good sense. So does bringing State and Federal clean economy finance initiatives together to boost their scale and impact. The Federal Government’s strong recent clean technology announcements can achieve even more in partnership with the States.”

Innes Willox

CPD Deputy Chair and Citi Australia Chair Sam Mostyn said the Climate and Recovery Initiative was a unique collaborative effort to help Australia’s response to cascading crises.

“The Climate and Recovery Initiative is all about the best ideas rising to the top to accelerate Australia’s COVID recovery and make huge gains towards a net zero emissions economy at the same time.”

“This initiative uniquely brings together the expert insights and commitment of some of Australia’s leading men and women from sectors and industries key to Australia’s success.”

Sam Mostyn

Business Council of Australia President Tim Reed said our COVID recovery must include addressing the risk and impact of climate change.

“Our recovery must include addressing the risk and impact of climate change, that means big opportunities for investment in clean energy and decarbonising technology.”

Tim Reed

National COVID-19 Commission Deputy Chair and Australian Climate Leaders Coalition Co-Chair David Thodey AO said the proposals could help to streamline efforts on climate across the federation.

“The Climate and Recovery Initiative has put important proposals on the table and the support for them has been encouraging. The proposals would streamline efforts on climate risk and resilience across the federation with a focus on boosting jobs and investment.”

David Thodey AO

Further reading

NSW Decarbonisation Innovation Study: Scoping Paper , NSW Chief Scientist & Engineer, March 2020

Greener After: A Green Recovery Stimulus for a post COVID-19 Europe , Pascal Lamy, 14 May 2020

Greening EU Trade 3: A European Border Carbon Adjustment Proposal , Pascal Lamy, 03 June 2020

Guide to Climate Scenario Analysis for Central Banks and Supervisors , The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, 6 June 2020

Climate Change and Monetary Policy: Initial Takeaways , The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, 6 June 2020

The Million Jobs Plan: A Unique Opportunity to Demonstrate the Growth and Employment Potential of Investing in a Low-Carbon Economy , Beyond Zero Emissions, June 2020

Joint Proposal for Economic Stimulus Healthy & Affordable Homes: National Low-Income Energy and Productivity Program , Australian Council of Social Service, June 2020

National Summit: Energy Efficiency and Australia’s Economic Recovery , Australian Council of Social Service & Australian Industry Group, June 2020

Far Reaching Climate Change Risks to Australia Must be Reduced and Managed, Australian Council of Social Service & Australian Industry Group, August 2020

Navigating Climate Change: CSIRO’s Climate Risk Initiative , CSIRO, August 2020

No Free Ride: Australia’s Economy and the Consequences of a Warming World post-COVID , Deloitte Access Economics, September 2020

The post Climate & Recovery Initiative appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

September 15, 2020

John Menadue Oration 2020

We are delighted to announce that we have rescheduled the John Menadue Oration for 2020 with Professor Megan Davis. Professor Megan Davis will deliver CPD’s third John Menadue Oration on Thursday 15 October 2020. You can register for the event here.

Professor Davis will speak on the theme: ‘Can Australia Deliver?’ The oration will take a big picture view of 2020, encompassing our COVID-19 response, the increased spotlight on Indigenous incarceration, and the future of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

This theme builds on Professor Davis’s work, as well as our 2018 Oration ‘Can the State Deliver?’, given by Mariana Mazzucato and the 2017 Oration, ‘Can Democracy Deliver?’, delivered by Marty Natalegawa, former Indonesian Foreign Minister.

Professor Davis is the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law and Pro Vice Chancellor Indigenous at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). She is also an Acting Commissioner of the NSW Land and Environment Court and an expert member of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Professor Davis is formerly Chair and expert member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Professor Davis’ renowned work on the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution will be known to many of you. As a constitutional lawyer and a member of the Referendum Council and the Expert Panel on the Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution, she helped craft the Uluru Statement. She is very much the constitutional legal scholar for our times.

Professor Davis is also a Commissioner on the Australian Rugby League Commission, and supports the North Queensland Cowboys and the QLD Maroons.

—

CPD’s flagship Oration has been named in honour of John Menadue AO, CPD’s founding Chairperson, in recognition of John’s contribution to public policy in Australia and to CPD. John served as Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet under Prime Ministers Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser, was Australia’s Ambassador to Japan and held senior roles in the business community.

—

This is an online event, hosted by the Centre for Policy Development via Zoom. Details will be sent to all registered attendees ahead of the event.

Register for the event here.

The post John Menadue Oration 2020 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 30, 2020

Putting Language In Place: Improving the Adult Migrant English Program

The Centre for Policy Development is pleased to announce the release of a new report, Putting Language In Place: Improving the Adult Migrant English Program.

The Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) has been the cornerstone of English language assistance for generations of migrants to Australia, providing language education and aiding new arrivals in their settlement journey. Now more than ever before, English language skills are vital in ensuring migrants can successfully participate in Australian economic and social life.

Putting Language In Place provides important context for the foundational changes to the AMEP announced by Minister Alan Tudge in his National Press Club Address, including expanding eligibility to all permanent migrants and citizens requiring English language support, relaxing the timeframe in which people can access this support, and making digital learning more accessible.

Whether recently arrived or resident for years, people with poor English will face additional barriers to full engagement in society and struggle to find work in an unforgiving post-COVID-19 labour market.

The report plots a reimagined and improved way forward for English language policy and programming. Building on the AMEP’s newfound flexibility, the report outlines how to create a more tailored and outcomes-driven program, which supports people on their full settlement journey, and allows them to adapt their English learning to the places in which they live and work. Key recommendations include:

promoting locally coordinated approaches to language learning, including through ‘local coordinators’

delivery of English language training on work sites and aligned to local employment contexts

expand the delivery of conversational, entry-level English language support in flexible environments, including co-located child-care

re-orienting AMEP to a settlement-first approach, where English language learning is integrated with settlement support, and ‘Pathways Counsellors’ to help guide people with what comes after the AMEP

the introduction of a licensing or accreditation arrangements that encourage specialist, flexible and sustained, high-performance service provision

Putting Language In Place was produced as part of CPD’s Cities and Settlement Initiative, and it complements CPD’s work supporting transitions to employment for people facing disadvantage in the labour market. CPD have been working with colleagues across the sector for over two years on ensuring English language assistance, and specifically a reinvigorated AMEP, more effectively supports economic and social participation for migrants. We are grateful to everyone who contributed their time and insights to this report, not least to Henry Sherrell, the report’s lead author.

Links and related reading:

Putting Language In Place: Improving the Adult Migrant English Program

Alan Tudge MP – National Press Club of Australia Address

Alan Tudge MP – Menzies Research Centre Address (February 2020)

Cities and Settlement Initiative

Settling Better: Reforming Refugee Employment and Settlement Services

Seven Steps to Success: Enabling Refugee Entrepreneurs to Flourish

The post Putting Language In Place: Improving the Adult Migrant English Program appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 11, 2020

CPD welcomes new CSIRO missions for Australia’s recovery and resilience

Today Australia’s national science agency, the CSIRO, has announced a suite of new ‘missions’ – major scientific and research collaborations aimed at achieving breakthroughs in response to Australia’s most pressing challenges.

In a National Press Club address to announce the new missions, CSIRO CEO Dr Larry Marshall described the program as part of a wider “mission of recovery and resilience” as Australia rebuilds from the COVID-19 crisis. “While COVID-19 will undoubtedly continue to disrupt, Australia will come together through this crisis and build a strong future in the process. We are calling for partners to join this Team Australia approach to solving what seem like unsolvable problems,” Dr Marshall said.

The CSIRO’s new program builds on growing global momentum for mission-oriented responses to pressing policy challenges. UCL Professor Mariana Mazzucato, who visited Australia as CPD’s guest in 2018 to deliver our John Menadue Oration, has been a global pioneer on mission thinking and driving a more collaborative, entrepreneurial role for the state in solving big problems. Mariana’s program in Australia included engagements with leading policymakers, institutions and innovators, including the CSIRO. It is encouraging to see these ideas taking hold, especially at a time when a mission-oriented approach can offer to much for Australia’s recovery and rebuilding process.

The new CSIRO program includes a new mission on building a new national climate risk capability to help navigate climate risk uncertainty. This responds directly to two key challenges that CPD has highlighted through our influential work on climate risk: the need for consistent, comparable data to enable better climate disclosure and responses, and the need for scaled up collaboration on climate across the public and provide sectors.

Most recently, our November 2019 Business Roundtable on Climate and Sustainability emphasised the need for “a significant ramp up in the availability and quality of decision-relevant information … in order for climate change to be appropriately addressed in the Australian economy.” It also highlighted that “more effective collaboration and leadership across the public and private sectors is an essential condition to understand and respond to climate risk. It concluded that that now was the time for a collaborative new economy-wide mission “to understand how climate risk impacts our financial system and economy, and what can be done about it.”

This new mission can help build more sophisticated, authoritative and accessible data on climate risk for companies and consumers, and support a more collaborative approach to the climate-related risks and opportunities that will shape Australia’s economic future. We will continue to work closely with the CSIRO as work continues towards the formal launch of the mission.

CPD CEO Travers McLeod said that the mission provides exactly the sort of launching pad Australia needs for greater public-private collaboration on climate risk. “New models for public-private sector collaboration are even more crucial as we recover and rebuild from bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic” he said. “We are delighted to see CSIRO stepping up to this challenge and look forward to continuing to work with the CSIRO team as the mission rolls out in coming months.”

A CPD media release on the mission is available here.

Links and related reading

CPD Business Roundtable on Climate and Sustainability

Climate change and the economy, speech by RBA Deputy Governor Dr Guy Debelle to Centre for Policy Development Public Forum, March 2019.

Can the state deliver?, CPD John Menadue Oration 2019 – Professor Mariana Mazzucato

On a mission to save democracy – Travers McLeod, Sam Hurley and Allison Orr

Risk of rising populism in the APS – Terry Moran and Travers McLeod

The post CPD welcomes new CSIRO missions for Australia’s recovery and resilience appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 10, 2020

Cities and Settlement Knowledge Hub

We’re excited to announce the launch of the Cities and Settlement Knowledge Hub, an online resource for the settlement services sector, service providers, policy makers and other stakeholders. It’s a curated portal that brings together up to date information on employment and settlement services, current data and statistics, reports and more.

The Knowledge Hub is also home to CPD’s evolving work around Community Deals, as well as other content from our Cities and Settlement Initiative (CSI). We intend for it to be a “living” resource, and we welcome any feedback or suggestions for content.

You can access the Knowledge Hub here.

We will also be producing a quarterly digital newsletter which will provide updates on the latest Knowledge Hub content, selected media, and other items of note from the Cities and Settlement Initiative.

As Australia enters a period of growing uncertainty, this initiative is more vital than ever. CPD is excited to be launching this valuable resource at such an important time.

The post Cities and Settlement Knowledge Hub appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 5, 2020

Caitlin McCaffrie: Andaman Sea Crisis: Is the region really better off in 2020?

Published as part of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law’s Andaman Sea Crisis series on 6 August 2020

The Asia Pacific is experiencing another major test of regional cooperation, reminiscent of the 2015 Andaman Sea crisis. In the first four months of 2020 there were more boat movements in the Andaman Sea than in all of 2019. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the vulnerability of forced migrants in refugee camps, on the move and at sea.

This article explores the governance and policy developments in regional institutions since 2015. In particular it focuses on four key developments: the agreement of two Global Compacts on Refugees and Migration, changes within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), changes within the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (Bali Process), and the establishment of the Track II Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM).

Having learned from the previous crisis, institutions in the region have taken steps to improve their capacity to address irregular migration. However, faced with another crisis, we are not seeing a different response.

1.Background to the 2015 Andaman Sea crisis

Five years ago, the world was horrified by images of thousands of Rohingya and Bangladeshi people stranded on trawlers in the Andaman Sea. The twin factors of a dramatic increase in boat movements and a sudden crackdown on trafficking and smuggling networks by the Thai Prime Minister led smugglers and traffickers to abandon boats full of people, adrift without food, water or medical care. Thousands were stranded in the open water, some for weeks. Some boats made it to Malaysia and Indonesia and disembarked, others were pushed back to sea by Thai, Indonesian or Malaysian authorities.

Widespread media coverage and international outcry ultimately prompted action. On 20 May 2015, Foreign Ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand met in Putrajaya, Malaysia. They “called on ASEAN to play an active role in addressing the issue in an effective and timely manner” and recommended “an emergency meeting by the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime to address the crisis.” This emergency meeting was convened on 2 July 2015, by which time most of those stranded at sea had disembarked.

Rather than through formal institutions such as ASEAN, the crisis was ultimately addressed through ad hoc multilateral cooperation. The key response was a Special Meeting on Irregular Migration in the Indian Ocean arranged by the Thai government. The meeting was held on 29 May 2015 and attended by the five most affected countries (Bangladesh, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia and Malaysia) along with 12 other countries, UNHCR, IOM and UNODC. At this meeting Malaysia and Indonesia agreed to: “provide humanitarian assistance and temporary shelter to those 7,000 irregular migrants still at sea provided that the resettlement and repatriation process will be done in one year by the international community.” While some states offered financial support, and some migrants chose to return to Bangladesh, few resettlement places were ultimately made available to those identified as refugees, placing the burden on the hosting countries.

Other examples of ad hoc cooperation include the roundtable convened by Indonesia in November 2015 on root causes of irregular migration of persons. The meeting focused on areas for practical cooperation on addressing root causes, building on the 2013 Jakarta Declaration, however was not instrumental in the immediate response to the boat movements earlier in the year.

The 2015 crisis exposed the lack of effective coordinated regional response mechanisms. While the nature of deaths at sea makes it is difficult to say with certainty how many people died as a result of the crisis, UNHCR estimates that at least 370 people died in the Bay of Bengal in 2015. Without the initiative shown by Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and others in the region in convening ad hoc meetings, this number would doubtless have been higher. However, such ad hoc resolutions do little if anything to bolster regional capabilities to address future crises. As the ADFM Secretariat wrote on the one-year anniversary of the Andaman Sea Crisis: “a one-off meeting should not be the norm for managing mass displacement events.”

2. The global and regional architecture is more developed than it was in 2015

Over the past five years, a number of international and regional developments have sought to strengthen the region’s capability to respond effectively to mass displacement and movements at sea. In 2018, the international community adopted two landmark Global Compacts: one on Refugees and one on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Previously, in response to the 2015 crisis, the Bali Process instituted a number of specific reforms to improve its capability to respond in the future. To a lesser extent, ASEAN has also bolstered its capacity to protect vulnerable groups, particularly victims of human trafficking. Another significant change to the regional governance landscape is the establishment of the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM), a second track forum designed to advance more effective regional responses to forced migration, which met for the first time in August 2015. This section explores each of these four institutional reforms in more detail, and other efforts in brief below.

2a) Global Compacts

The two Global Compacts have provided an overarching context within which to work collaboratively on issues of refugees and migration. The genesis of the two Global Compacts is the September 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. Over the ensuing two years, the international community developed the text for two distinct agreements, which were each adopted in December 2018. Although not legally binding, these two compacts provide a good basis for renewed regional coordination and leadership on critical issues concerning refugees and migrants at risk. Considering the current state of global politics, it is hard to imagine similar documents receiving such widespread support today.

The Refugee Compact was drafted by UNHCR in consultation with government and non-government actors, and ultimately adopted in the UN General Assembly in December 2018. It received widespread support: all ASEAN member states and all but one Bali Process member states voted in favour of adopting the Refugee Compact at the General Assembly in December 2018 (the United States voted against both compacts). It has four stated objectives, namely to “(i) ease pressure on host countries; (ii) enhance refugee self-reliance, (iii) expand access to third country solutions and (iv) support conditions in countries of origin for return in safety and dignity.” The Compact also establishes a ‘Global Refugee Forum’ to be convened every four years. The first of these fora was held in December 2019 and resulted in about 1400 separate pledges.

In contrast to the Refugee Compact, the Migration Compact was developed through a process of negotiation with states, and thus is more contested and ultimately had a lower rate of adoption. In our region, the Migration Compact had the support of eight of ten ASEAN member states (Brunei Darussalam did not vote and Singapore abstained), and 36 of 45 Bali Process members. Australia chose not to adopt the Migration Compact, which has been recognised as a missed opportunity, particularly given its position as Co-Chair of the Bali Process, as discussed below. The Migration Compact represents a commitment by states to “enhanced cooperation on international migration in all its dimensions” and contains 23 objectives, including Objective 9 on combatting smuggling, Objective 10 on combating trafficking and Objective 23 on international cooperation.

Ratification of the United Nations Refugee Convention is low in the Asia Pacific region, although some states do have provisions for protection of vulnerable migrants within their national policies, such as the 2016 Indonesian Presidential Regulation, discussed in greater detail here. In this context the existence of documents like the Global Compacts, outlining broadly agreed principles on often fraught issues such as migration and protection, is a significant milestone.

2b) ASEAN

Although the ten member states of ASEAN are all significantly impacted by migration, the regional body’s engagement on migration issues has only developed gradually over time. As ADFM Co-Convenor Sriprapha Petcharamesree, from the Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies at Mahidol University, has noted, “issues of forced migration have never been properly discussed or addressed in ASEAN by the member states.” However, one priority migration issue within ASEAN has been protection of migrant workers, due to high labour mobility to and from member countries.

There have been some important reforms within ASEAN since 2015; most significantly the signing of the ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (ACTIP) and development of the associated Bohol Work Plan. ACTIP entered into force in March 2017, and made Asia the second region (after Europe) to have a multilateral agreement on trafficking in persons. Article 1 recognises the need for cooperation among member states to meet the twin objectives of preventing and combating trafficking in persons and protecting and assisting victims. The Bohol Work Plan – the first ever cross-sectoral work plan developed by ASEAN – has been described as an “innovative and comprehensive approach to [trafficking in persons].”

Implementation of ACTIP, and the ability of member states to put the legal framework into practice, remain key issues. Although ACTIP and the Bohol Work Plan are steps forward for the region, ASEAN bodies remain insufficiently resourced to support member states in effectively implementing their commitments. To date, too few trafficking victims have been identified and supported, or perpetrators prosecuted. Another limitation is that ACTIP, being an ASEAN convention, does not cover Bangladesh and its counter-trafficking efforts, which are important to consider when looking at boat movements in the Andaman Sea. Bangladesh does have its own programs to address human trafficking and migrant smuggling; however, greater coordination and alignment between these and the work of ASEAN would be beneficial.

Other promising developments within ASEAN are the recent renewed commitment to the ASEAN-Australia Counter-Trafficking Program, and the April 2019 release of Regional Guidelines and Procedures to Address the Needs of Victims of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, developed by the ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children.

Significantly, ASEAN has also been playing a role in Rakhine State. In late 2018, the Government of Myanmar invited the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Affairs (AHA Centre) to “despatch a needs assessment team to identify possible areas of cooperation in Rakhine State to facilitate the repatriation process.” At its Bangkok Summit in November 2019, ASEAN established an Ad-Hoc Support Team to assist repatriation and reaffirmed its support for “a more visible and enhanced role of ASEAN”. The ASEAN Emergency Response and Assessment Team and the AHA Centre have been active in working to advance the repatriation process with both Myanmar and Bangladesh, including conducting a Preliminary Needs Assessment in Rakhine State and visiting Cox’s Bazar. The AHA Centre has traditionally worked on emergency response to natural disasters, and the Preliminary Needs Assessment was criticised for a lack of focus on protection concerns. The impact of ASEAN’s involvement in the repatriation process so far remains unclear, and progress remains slow. Suggestions have been made to boost the AHA Centre’s capacity to handle protection related issues, potentially in partnership with others.

2c) Bali Process

The Bali Process was established in 2002, is led by Indonesia and Australia, and over the years has grown to include 45 member countries, four international agencies (UNHCR, IOM, UNODC and ILO), 18 observer countries and nine observer agencies. The group continues to be co-chaired by Australia and Indonesia, with a Steering Group comprised of Australia, Indonesia, Thailand, New Zealand, UNHCR and IOM. An Ad Hoc Group was established in 2009 and now comprises 16 ‘most affected countries’ plus UNHCR, IOM and UNODC.

Following the Andaman Sea crisis, the Bali Process recognised it lacked the mechanisms and policies necessary to respond effectively. The Bali Declaration, made following the sixth Ministerial Meeting on 23 March 2016, recognised the need to “provide safety and protection to migrants, victims of human trafficking, smuggled persons, asylum seekers and refugees, whilst addressing the needs of vulnerable groups including women and children and taking into account prevailing national laws and circumstances”. This commitment was reaffirmed by the Bali Process in its 2018 Declaration.

In 2016 the Bali Process also conducted a review into its response to the Andaman Sea Crisis, which found that “at the time there was little functioning capability to deal with root causes of displacement in the affected countries, and that there was little functioning capability to deal with the consequences for the region when mass displacement occurs”. The review recognised the “need for more agile and timely responses by Bali Process members”.

In direct response to this crisis, the Bali Process created a new emergency response mechanism – the Consultation Mechanism – as well as an operational level Task Force on Planning and Preparedness. These mechanisms aim “to standardise various national approaches, develop early warning capabilities and coordinate action” in order to facilitate an effective response to another crisis. The Consultation Mechanism is non-binding and voluntary. The circumstances necessary to warrant triggering the Mechanism are i) circumstances must be related to irregular migration, people smuggling or trafficking in persons; ii) more than one member country is affected; and iii) significantly affected countries are members of the Bali Process. Triggering the mechanism authorises Co-Chairs to consult or convene meetings to discuss urgent irregular migration issues, as well as formulate possible regional responses.

It sadly did not take long before circumstances necessitated the first test of these new mechanisms. The sudden escalation in violence in Rakhine State on 25 August 2017 led to a mass exodus of Rohingya from Myanmar to Bangladesh. In response, on 13 October 2017, the Bali Process Co-Chairs activated the Consultation Mechanism, which facilitated confidential dialogue between the Bali Process Steering Group and affected countries. As a result of triggering the Consultation Mechanism, the Co-Chairs remain engaged on the issue, and have undertaken two ‘good offices’ visits to Myanmar and Bangladesh in May 2018 and November 2019.

The full Task Force on Planning and Preparedness has met five times since its creation, most recently in February 2020, as COVID-19 was beginning to spread around the globe. This theme of this meeting was ‘cooperative frameworks to address irregular maritime movement.’ At the meeting, the group reaffirmed its core principles, including non-refoulement and saving lives at sea. Despite the meeting being held so recently and on such a pertinent topic, it has not translated into measurable improvement in the ability of countries to cooperate in responding effectively to those stranded at sea. A virtual ad hoc policy experts gathering of the Task Force on Planning and Preparedness was held on 14-16 July 2020, however at the time of writing the co-chairs statement is yet to be made public.

Beyond mechanisms directly linked to the Andaman Sea review, the Bali Process has also been active in building longer-term capacity of members to address drivers of forced migration through the work of the Regional Support Office and Government and Business Forum. The Regional Support Office works to support and strengthen practical cooperation on refugee protection and international migration, including through developing policy guides, trainings and information sharing. The Government and Business Forum seeks to work with the private sector and governments to expand legitimate labour market pathways, promote ethical business practices and strengthen policy and legislative frameworks that counter trafficking and smuggling. In this context we should also note Australia’s 2018 Modern Slavery Act, which now requires businesses to report on risks of modern slavery in their supply chains or operations.

2d) Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration

The fourth significant change to the regional governance landscape since 2015 is the creation of a Track II process dedicated to migration issues: the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM).1

The ADFM was established by the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) in Australia and has been run by a Secretariat of policy think tanks in Thailand (Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University), Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and until recently Malaysia (Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia).

The ADFM builds trust and cooperation among key actors in the region, often on difficult or fraught topics. The forum brings together senior officials and experts from nine regional countries, UNHCR, IOM, ASEAN and the Bali Process, each of whom participate in their personal capacity and under the Chatham House Rule of non-attribution. Since its establishment in 2015 the ADFM has met nine times in the region; in Bangladesh, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Australia.

A central feature of the Dialogue is that it aims to provide governments and institutions with practical, implementable ideas, rather than offering general advocacy. This pragmatic orientation means the format, content and timing of meetings are designed to ensure they make most of existing opportunities. For example, by scheduling the ADFM’s second meeting in Bangkok in January 2016, immediately before the Bali Process senior officials’ meeting held there, and six weeks before the Bali Process Ministerial Meeting, the dialogue was able to provide timely space for creative policy debate and discussion and allow for the participation of senior officials.

At its fourth meeting in March 2017, the ADFM accepted the request from the Bali Process to become an ongoing source of policy advice on forced migration. ADFM advice to Bali Process Co-Chairs ahead of their sixth Ministerial Meeting was important in decisions made at that meeting, including establishing the Consultation Mechanism and to authorise the Andaman Sea Review. The ADFM assisted in conducting this review. The review’s recommendations were adopted by Bali Process senior officials in November 2016. The ADFM Secretariat also recommended the activation of the Bali Process Consultation Mechanism after discussions at the ADFM’s fifth meeting in September 2017.

The ADFM has also worked with ASEAN, including advising on the establishment of a focal point system for more effective implementation of ACTIP, which was endorsed by the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime in September 2017 and is being implemented by the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime. The ADFM has also advised on the two global compacts on migrants and refugees at conferences in Bangkok and Geneva.

The remit of the ADFM is broad; however, given the timing of its first meeting in August 2015, just a few months after the Andaman Sea Crisis, it has maintained a strong focus on how the region can better respond to the mass displacement of the Rohingya. To this end, the ADFM Secretariat and a team of researchers conducted an assessment of the risk of human trafficking, migrant smuggling and related exploitation arising from the mass displacement of Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar. The assessment found that the risk factors for trafficking were high within the camps and likely to increase unless urgent steps were taken to address both the immediate needs of the displaced Rohingya and their long-term prospects, namely through pursuit of safe, dignified, voluntary and sustainable repatriation to Myanmar.

The ADFM met most recently in February 2020 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down international travel. Prior to the meeting, the ADFM Secretariat led a smaller group of senior officials and experts to Cox’s Bazar, to follow up on its trafficking risk assessment and observe how the situation had changed since then. The statement the ADFM Secretariat released after the meeting expressed concern that “the risks of further people movement, trafficking and the prospect of loss of life, remain high, and are likely to grow with time” and this concern has only grown in the weeks and months since their time in Bangladesh.

2e) Other noteworthy efforts

Although not covered in depth here, it is also worth noting that there have been other important actors and work focusing on this issue over the past five years, such as the work of UNHCR and IOM in strengthening national protection frameworks in the region. In 2016, IOM officially joined the United Nations network, allowing greater alignment of work between agencies. In 2019, UNHCR decentralised its regional programming, in part to strengthen alliances with regional agencies and respond more rapidly to emergencies. Meanwhile, the final report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State put forward 88 recommendations in August 2017 to address political, social, economic and humanitarian challenges in Rakhine State.

3. The stakes are now higher

At the same time that regional institutions have been working to improve their capacity to respond to mass displacement, challenges in the region have intensified. Indeed, two major factors have dramatically changed the lay of the land and raised the stakes for responding to forced migration challenges.

3a) World’s largest refugee camp

The Asia Pacific region now hosts the largest refugee camp in the world. There are approximately one million Rohingya living in camps in Cox’s Bazar District, Bangladesh. Most fled their homes in Myanmar in August 2017, with about 500,000 crossing the border within the first month. The Government of Bangladesh has delivered a generous and effective humanitarian response to date, hosting the displaced Rohingya for nearly three years. The support of international donors and the humanitarian sector has helped to stabilise the crisis and provide ongoing support to both the Rohingya and Bangladeshi host community, although the Joint Response Plan remains critically underfunded.

As we approach the third anniversary of the 2017 Rohingya crisis, both Bangladesh and Myanmar remain publicly committed to voluntary, safe, dignified and sustainable repatriation of displaced persons. Yet progress has been slow. Irregular movements by sea and land are also continuing, and there are concerns about the shrinking protection environment for Rohingya living elsewhere such as Saudi Arabia and India. Concerns about the risk of trafficking, smuggling and exploitation continue to grow the longer the situation stagnates without a feasible resolution on the horizon, particularly given recent measures to restrict internet access and build a fence around the camps. The ADFM Secretariat again highlighted these concerns in a press release after their Dhaka meeting.

3b) A global pandemic

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has had harmful repercussions for migrants and refugees around the world. Many countries have focussed their attention inward, using border closures and travel bans in an attempt to manage migration to protect public health. Resources and officials working on forced migration have been diverted to the pandemic response. These trends will expose many vulnerable migrants, asylum seekers and refugees to greater risks, and so test the recently signed global compacts and their spirit of international cooperation.

Those living in crowded refugee camps such as Cox’s Bazar are unable to follow public health guidelines like social distancing. The first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the camps on 14 May 2020, and “as of 23 July 2020 there have been 64 confirmed cases in the refugee camps, and six fatalities. The Cox’s Bazar host community has seen 3,166 confirmed cases and 52 deaths.”

Among the unintended consequences of various national public health responses is increased risk of human trafficking. Not only are border closures likely to lead people to seek out smugglers to facilitate movement, but stay-at-home public health orders make it harder for media and other agencies to monitor the situation and support vulnerable groups. Loss of employment among migrant workers who are forced to return home to limited economic prospects will make some more vulnerable to false offers of employment by those seeking to exploit the desperate.

Worryingly, the 2016 Review into the Bali Process’s response to the Andaman Sea crisis found that: “it was the media reporting to the world on the ships stranded at sea, the discovery of graves and more profoundly the lack of coordination and agreement in the region that prompted action”. Now that the world’s attention is focussed on COVID-19, and in many cases journalists are confined to their homes, it’s already evident that public pressure is not as strong and effective as it was in 2015.

4. The current crisis: Are we any better off than we were in 2015?

Tragically, this special series could not be more timely. Five years after the Bali Process Review recognised the “need for more agile and timely responses” to mass displacements, boats of vulnerable migrants are again adrift in the Andaman Sea. In the first four months of the year alone, at least 135 Rohingya have died or gone missing in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal. Boat movements rose between March and May: UNHCR estimates 1,800 people have disembarked so far this year, and 200 people remain stranded at sea.

Echoing the experience of 2015, many Rohingya who have now reached safety report being stranded at sea for months. One boat is known to have disembarked in Malaysia and another safely disembarked in Aceh, Indonesia. Others have been intercepted and pushed back to sea, or have returned to Bangladesh, where approximately 300 are understood to have been quarantined on Bhasan Char island since May. International agencies have expressed concerns in the past about the viability of the island to support a population, given its flood-prone nature.

Although the numbers are not currently at the scale of 2015, the unprecedented context of the COVID-19 pandemic and mass displacement in Cox’s Bazar create the conditions in which the situation could certainly get much worse. Despite the steps outlined above to strengthen the region’s ability to respond collaboratively and effectively to just these types of situations, we are once again seeing a prioritising of national interest over coordinated action.

While the Global Compact on Refugees, supported by all states in the region, affirms the principle of international solidarity, burden- and responsibility-sharing. These principles have unfortunately not been on show in the region’s response to those most vulnerable, stranded at sea. ASEAN has held numerous regional and bilateral meetings since the COVID-19 crisis began, and issued no less than nine joint statements between February and June on issues ranging from food security, defence cooperation and tourism. However, the boat movements have not been on the official agenda. On 26 June 2020, ASEAN leaders met virtually for their first ASEAN Summit since the pandemic hit, but the boat movements were absent from the resulting Chairman’s Statement.

The ADFM Secretariat convened a virtual meeting of senior experts in late April to address the implications of COVID-19 on forced migration, including responses to the new Andaman Sea crisis. Following the meeting, the Secretariat made recommendations to Australian and Indonesian Governments as Co-Chairs of the Bali Process. Those recommendations outlined how the Bali Process could use the reforms of recent years to elevate senior official and ministerial engagement on boat movements and other issues of concern, particularly in light of COVID-19 and its impact on displaced populations, in order to facilitate more effective regional responses.

On 6 May, UNHCR, UNODC and IOM called on states in the region to “uphold the commitments of the 2016 Bali Declaration as well as ASEAN pledges to protect the most vulnerable and to leave no one behind”. Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon also called for the Bali Process Co-Chairs to activate the Consultation Mechanism, and also to ASEAN to do more to support refugee resettlement and the response in Cox’s Bazar. The Bali Process has made no public statement on the matter as yet, but Australian and Indonesian senior officials have convened discussions about the issue.

In June, Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne reaffirmed Australia’s commitment to the international community and “constructive, multilateral engagement”. It is thus timely that the ADFM Secretariat is taking forward a proposal supported by its members at its last meeting to conduct a strategic assessment of future regional priorities for forced migration responses, including review of progress on Bali Process initiatives since the 2016 Bali Declaration. Such an assessment could shine a light on implementation gaps and areas to prioritise for more effective future responses, including mapping future forced migration scenarios and ongoing drivers of displacement.

It is certainly challenging at the moment for governments and diplomats to transition rapidly to working together in a virtual, travel-constrained environment. Innovative and creative uses of technology will be essential if regional institutions are to fulfil their mandates during the pandemic.

At the five-year anniversary of the Andaman Sea crisis, regional institutions have built greater capacity to respond more effectively to mass displacement, human trafficking and migrant smuggling. However, for these reforms to be credible, they have to be put into practice. Faced with a displacement crisis coupled with a global pandemic, regional institutions have once again seemingly failed to respond effectively to protect the most vulnerable. Will anything have changed by the ten-year anniversary?

The post Caitlin McCaffrie: Andaman Sea Crisis: Is the region really better off in 2020? appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

August 3, 2020

Terry Moran: Consultants being public servants – The Select Committee

Published in The Mandarin on 04 August 2020

Malcolm Turnbull has bemoaned it. Our own Bernard Keane has criticised it. The Thodey Review has raised concerns about it. The ‘cult of the consultant’ has a grip on the public sector – like never before.

We have asked members of The Select Committee – The Mandarin Brains Trust exactly what they think about the growing use of consultants in federal, state and territory public services across Australia.

More specifically, we asked:

What is the appropriate level of the use of consultants in the public service? Has it gone too far? Are consultants doing too much core/routine work or are they providing a vital service?

You can access the full article (paywall) here.

The post Terry Moran: Consultants being public servants – The Select Committee appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 21, 2020

Community Deals

What are Community Deals?

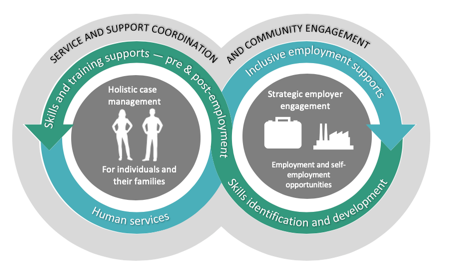

Community Deals are a local place-based model aiming to boost economic and social participation.

They are a genuine partnership between government, business and community that allow a consortia of local actors to adapt programming locally to achieve concrete outcomes for their community.

Community Deals feature holistic, tailored services wrapped around a family and individual, and strategic engagement of employers and local industry.

They harness sustained support from local, state and federal government, as well as non-government and philanthropic resources. They are distinct in that they are vertically integrated into national and state service systems.

They use a ‘tight-loose-tight’ framework (tight on objectives, loose on method of implementation and tight around evaluation) that gives confidence to funders and partners to invest in an ongoing and sustainable way.

The Community Deals model is based on good practice place-based approaches in Australia and overseas.

Community Deals Impact

Wyndham Employment Trial

Wyndham is a growing municipality on the urban fringe of Melbourne and home to a diverse community, including many refugees and other migrants. Wyndham City Council (WCC) and local partners have developed the Wyndham Employment Trial to boost economic participation for humanitarian migrants. The trial is based on the Community Deals model and commenced in mid-2019. CPD worked alongside WCC and local partners to establish the trial. As of 30 June 2019 there were 768 humanitarian migrants on the Werribee jobactive regional caseload. These people were on the jobactive caseload for an average of 80 weeks.

Outcomes/Impact

At 1 April 2020, after approximately 9 months of the trial:

The post Community Deals appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 12, 2020

Travers McLeod: Democracy can never be sublet

Published in The Australian on 13 July 2020

Victoria’s decision to give private security contractors responsibility for quarantine hotels is the subject of a judicial inquiry, which will reveal the true cost of this decision and whether it was right. But the reported poor performance of those contractors suggests that we should consider government reliance on such outsourcing more generally.

Australians are uneasy about outsourcing essential services. The Centre for Policy Development examined attitudes to democracy and the role of government and service delivery in 2017 and 2018. Australians believed services delivered by government were higher quality and more affordable, accessible and accountable than those delivered by private companies or charities. Three in four thought it was important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver social services directly instead of paying others to do it.

Last month, we asked the same questions again. The result was striking. Nine in 10 now think it important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver social services directly. The view was emphatic regardless of voting intention, although Coalition voters were more in favour.

This isn’t about hotels. It’s about who you trust to deliver when the outcome matters much more than profit — when your life might depend on it. Recent history hasn’t been good for outsourced services. The aged care royal commission stated it is “a myth that aged care is an effective consumer-driven market”, and it slammed the system for too often neglecting older Australians

The biggest mountain Australian governments need to climb now is the issue of jobs, yet our national employment services system, Jobactive, is all outsourced. Its caseload grew from about 615,000 at the start of 2020 to almost 1.4 million by the end of May. And that’s before JobKeeper finishes.

Australia should boast the world’s best employment services system after three decades of uninterrupted economic growth. But a 2018 review led by Sandra McPhee found our system had to do “much better”. Case managers averaged 148 clients. Providers were in touch with only 4 per cent of employers. The system was pre-digital, designed for a world without Google and Seek. It wasn’t cheap either, costing about $1.3bn a year.

With so much to fix, contracts with job service providers were extended to 2022 just before last year’s federal election. Trials started of a new digital model and specialised wraparound services for the most disadvantaged jobseekers. Today the system is overwhelmed.

We should have moved faster. Climbing the jobs mountain with Jobactive will be like doing the Tour de France on a bike with a single gear.

Noel Pearson has called for a government jobs guarantee due to COVID-19 and for this to be co-ordinated by local governments. There is merit in exploring this. Many local government authorities are highly effective. Those able to deliver should be given an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities in solving problems critical to their communities, with local accountability and more sophisticated funding systems.

The need for local approaches that tap into community networks has been a common thread of reviews of employment services and settlement services. David Thodey’s public service review agreed and sought to embed public delivery much more effectively in place.

The Centre for Policy Development has shown how Community Deals can do this, connecting funding sources and governance in local networks to boost economic and social outcomes, using the more efficient model recently backed by the Prime Minister for vocational education and training. The Brotherhood of St Laurence has a similar approach focused on youth unemployment.

This isn’t about choosing government over private or charitable providers, or always choosing local government as the co-ordinating authority. It’s about government getting back into the service delivery game alongside providers instead of just funding them.

Given 90 per cent of Australians want this, it’s worth asking why. The answer may be found in our view of democracy.

Last month, we asked Australians for the third time what they think the main purpose of our democracy is. The answer now three times as popular as any other is ensuring all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable. A total of 45 per cent of Australians chose this as the main purpose of our democracy (up from 36 per cent in 2018 and from 35 per cent in 2017), well ahead of other answers like ensuring people are free to decide how to live (15 per cent), ensuring no person or organisation has too much power (14 per cent) or electing representatives to make decisions on your behalf (13 per cent).

These figures suggest the bushfires and the virus have sharpened attitudes about our democracy and faith in government.

Australians expect government to be an active player in service delivery. And we want democracy to improve the lives of others, particularly the most vulnerable. We want that in the best of times and particularly in the worst of times. Such attitudes are instructive as governments face the biggest labour market disruption in a generation.

Fixing Jobactive to deliver during and after the pandemic cannot be achieved with new licensing contracts alone. It will take courage by governments to lead on the ground as an employer, co-ordinator, procurer, licensor and service provider. It will take honesty about how the recovery will be a grind and how we need to do clever things to make it work. More of the same is a recipe for disaster.

The post Travers McLeod: Democracy can never be sublet appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

July 9, 2020

Terry Moran: Reimagining Government

CPD Chair Terry Moran appeared as one of the panellists on a webinar series jointly hosted by the Centre for Public Impact (CPI) and the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). You can access the webinar here.

Reimagining Government explored the idea of “the enablement paradigm” – a new model which believes that the core role of government is to create the conditions in which communities can flourish.

The post Terry Moran: Reimagining Government appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Centre for Policy Development's Blog

- Centre for Policy Development's profile

- 1 follower