Jessica Knauss's Blog, page 9

January 29, 2018

Oviedo: Medieval Paint and Alfonso II's Religio-Political Statement

San Julián de los Prados, Oviedo

San Julián de los Prados, OviedoAll photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss Oviedo was a hugely important urban center in the early Middle Ages, a focal point for the largely rural Kingdom of Asturias, which was the first area to be "reconquered" after Moorish domination began in 711. I was thrilled to visit it for the first time last November.

San Julián de los Prados is a pre-Romanesque gem of a church one kilometer from Oviedo's urban center. I trudged through the traffic and the rain in the cold of the early morning, suffering with my first cold of the season but determined to make my trip to Oviedo all about the early Middle Ages.

On the side of a highway, nothing much distinguishes San Julián from this side, but if you look closely, you can see the messy-looking but super skilled bricklaying technique and the archway characteristic of the first half of the ninth century, the reign of Alfonso II.

On the side of a highway, nothing much distinguishes San Julián from this side, but if you look closely, you can see the messy-looking but super skilled bricklaying technique and the archway characteristic of the first half of the ninth century, the reign of Alfonso II.Alfonso II, known as the Chaste, also founded Oviedo Cathedral and was the first to make the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela from here.

On the side closest to the highway, this gorgeous stone jalousie window let in latticed sunlight in a very particular spot we'll glimpse below.

On the side closest to the highway, this gorgeous stone jalousie window let in latticed sunlight in a very particular spot we'll glimpse below. The back of San Julián, with its surprising view back to Oviedo's cathedral tower, is obviously pre-Romanesque, with its three-part window and the smaller, lovely jalousies.

The back of San Julián, with its surprising view back to Oviedo's cathedral tower, is obviously pre-Romanesque, with its three-part window and the smaller, lovely jalousies. The architects and artists of the ninth century didn't value uniformity. If someone ordered three windows, the craftsmen made each one beautifully different.

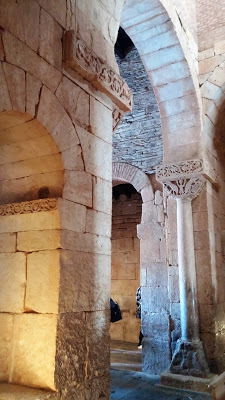

The architects and artists of the ninth century didn't value uniformity. If someone ordered three windows, the craftsmen made each one beautifully different.They don't let you take pictures inside, but I risked who knows what kind of admonishment or banishment with my silent, flash-free camera because this interior must be seen. They said it had original painting in it, but I was not prepared for the floor-to-ceiling glory of what was inside. Geometric shapes and a celestial cityscape, complete with chambers and bed linens, and color, color, color! They found these paintings underneath layers of lime-and-chalk (later centuries' hygiene methods, they said). My photos aren't exactly professional, but when you're in San Julián, you only have to use a little imagination to place yourself back in the ninth century, in contrast to most other medieval sites, where you have to use all your imagination and still can't picture it.

Here we see the side of the largest part of the church, where the less noble folk would've gathered to hear mass--basically the peanut gallery. It's not the most impressive spot, but it's still an eyeful.

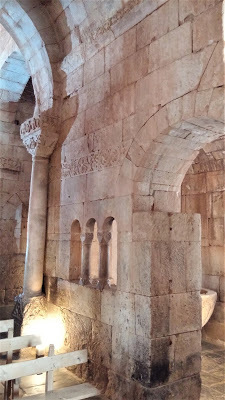

Here we see the side of the largest part of the church, where the less noble folk would've gathered to hear mass--basically the peanut gallery. It's not the most impressive spot, but it's still an eyeful.  This is the other side of the large window we see from the outside above. It's to the right side of the main altar. I wish the pictures did it more justice. I stood there dumbfounded, looked and looked, and found myself incapable of taking it all in. Is that the same impression ninth-century worshippers would've had as they stood there smelling incense and listening to Latin speech and song?

This is the other side of the large window we see from the outside above. It's to the right side of the main altar. I wish the pictures did it more justice. I stood there dumbfounded, looked and looked, and found myself incapable of taking it all in. Is that the same impression ninth-century worshippers would've had as they stood there smelling incense and listening to Latin speech and song?  This gallery is to the left side of the main altar. The archway in front separates this area from the main congregation area, and nobles would've had spaces reserved for them here.

This gallery is to the left side of the main altar. The archway in front separates this area from the main congregation area, and nobles would've had spaces reserved for them here.See the indentations in the wall above the bench and doorway? That's where the king's box would've been. It's across from the large jalousie window, which is placed exactly so that during mass, the sun shines through it with full brightness. (That's partially why there's less paint surviving on this wall.)

After all the people were settled and ready for mass, Alfonso II would appear on this balcony in his finest robes, embroidered with cloth of gold and decked out in all the jewels of the realm, surrounded by images of the celestial city, and the sun would create a spectacular scene of jaw-dropping splendor.

This was Alfonso II's public service announcement, a proclamation that he was indeed the chosen intermediary between God and the people.

I staggered out of San Julián, overwhelmed with the aliveness of history. I later learned that the three-part window in back is the only hint of a secret chamber destined for who knows what purpose.

I staggered out of San Julián, overwhelmed with the aliveness of history. I later learned that the three-part window in back is the only hint of a secret chamber destined for who knows what purpose.This was only the beginning of the mind-blowing experiences for a medievalist in Oviedo.

Published on January 29, 2018 00:30

January 1, 2018

Segovia's Medieval Treasures: Ayllón

Ayllón with its Martinete tower and Baroque bell gable of Santa María

Ayllón with its Martinete tower and Baroque bell gable of Santa MaríaAll photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss Spanish mornings are long. We got on the tour bus at 8 a.m., having swallowed some churros or other fast breakfast food, and we thoroughly experienced Santa María de la Riaza, which would've been enough medieval art for any other day or week, and then made it to Ayllón, but it was still nowhere near lunchtime.

Ayllón's Plaza Mayor Although Ayllón has works of art from most time periods, our tour focused on Romanesque standouts and the Gothic expressions inside them, and we still had our hands overfull.

Ayllón's Plaza Mayor Although Ayllón has works of art from most time periods, our tour focused on Romanesque standouts and the Gothic expressions inside them, and we still had our hands overfull. In fact, Romanesque churches were so abundant in the province of Segovia that—surprise, surprise—people in later time periods didn't value them, care for them, or even bother to keep them in one piece sometimes. The first monument we saw were the ruins of San Nicolás, which was converted into the gate of the municipal cemetery in the nineteenth century by demolishing everything but one doorway.

In fact, Romanesque churches were so abundant in the province of Segovia that—surprise, surprise—people in later time periods didn't value them, care for them, or even bother to keep them in one piece sometimes. The first monument we saw were the ruins of San Nicolás, which was converted into the gate of the municipal cemetery in the nineteenth century by demolishing everything but one doorway.

These fighters are so weathered, I would've misinterpreted them

These fighters are so weathered, I would've misinterpreted them without the expert guidance of Arteguías. They scavenged a few column capitals and placed them according to their own tastes. We took the opportunity to study them at length, identifying heads, angels, and medieval handfighters.

Another case of Romanesque reappropriation was Santa María la Mayor, a mostly Baroque edifice close to the Plaza Mayor with an impressive bell gable.

Another case of Romanesque reappropriation was Santa María la Mayor, a mostly Baroque edifice close to the Plaza Mayor with an impressive bell gable. The lion attacks represent the way the flesh passes on.

The lion attacks represent the way the flesh passes on.  Left: Weighing souls.

Left: Weighing souls. Right: An angel holds up a monogram of Christ that has its Alpha and Omega letters transposed. On the northern and eastern outer walls of Santa María, restorers placed Romanesque reliefs that probably originated in the church the Baroque builders replaced. The figures include lions pouncing on humans, an angel with a special monogram of Christ, and an instance of weighing souls in judgment. Why did they place those last two so high?

In the gorgeous porticoed Plaza Mayor, the main attraction was the church of San Miguel. It's now used as Ayllón's tourism office, and is a museum of marvels, inside and out. The apse is partially buried under street level, but that put the corbels that much closer to our avid eyes.

In the gorgeous porticoed Plaza Mayor, the main attraction was the church of San Miguel. It's now used as Ayllón's tourism office, and is a museum of marvels, inside and out. The apse is partially buried under street level, but that put the corbels that much closer to our avid eyes. Here we see many corbels depicting people at various tasks, including a delightful one with a stoneworker doing some fine detail carving with one of his enormous medieval tools. Note the intricate crosshatching above and the quatrefoil flowers between the corbels.

Here we see many corbels depicting people at various tasks, including a delightful one with a stoneworker doing some fine detail carving with one of his enormous medieval tools. Note the intricate crosshatching above and the quatrefoil flowers between the corbels. The southern entrance eroded quite a bit before they put a porch shelter over it. Its geometric decoration has heavy Sorian influence.

The southern entrance eroded quite a bit before they put a porch shelter over it. Its geometric decoration has heavy Sorian influence. Different masonry styles and a mysterious balcony

Different masonry styles and a mysterious balcony

I'm really impressed with María Álvarez de Vallejo. She's an avid reader even now! Inside, the nave is almost square and may have been built on a previous mosque. The different stones used in Muslim and Christian construction are clearly visible in the bare walls. Highlights include a balcony with mysterious Gothic painting, various Gothic burial niches, and the alabaster tomb of María Álvarez de Vallejo and her husband, Pedro Gutiérrez, secretary and treasurer of the Marquises of Villena, Diego López Pacheco and his second wife, Juana Enríquez. It may have been made by the same artists who completed the alabaster tomb of Fernando and Isabel in the Royal Chapel in Granada. Most of the damage was caused by Napoleonic troops as they came through!

I'm really impressed with María Álvarez de Vallejo. She's an avid reader even now! Inside, the nave is almost square and may have been built on a previous mosque. The different stones used in Muslim and Christian construction are clearly visible in the bare walls. Highlights include a balcony with mysterious Gothic painting, various Gothic burial niches, and the alabaster tomb of María Álvarez de Vallejo and her husband, Pedro Gutiérrez, secretary and treasurer of the Marquises of Villena, Diego López Pacheco and his second wife, Juana Enríquez. It may have been made by the same artists who completed the alabaster tomb of Fernando and Isabel in the Royal Chapel in Granada. Most of the damage was caused by Napoleonic troops as they came through! Ayllón is also home to several late Gothic palaces, their facades packed with heraldry symbolism and the Isabelline version of the decorative orbs we saw in Romanesque Santa María de la Riaza.

Ayllón is also home to several late Gothic palaces, their facades packed with heraldry symbolism and the Isabelline version of the decorative orbs we saw in Romanesque Santa María de la Riaza. In another part of town, the Church of San Juan might've suffered the same fate as San Nicolás (or worse) if it hadn't been for the passion and financing of Ayllón's native son, Pedro. He loved the ruined church when he was a boy, and always hoped to own it one day. His dream came true when it was threatened with bulldozing, and he saved it.

In another part of town, the Church of San Juan might've suffered the same fate as San Nicolás (or worse) if it hadn't been for the passion and financing of Ayllón's native son, Pedro. He loved the ruined church when he was a boy, and always hoped to own it one day. His dream came true when it was threatened with bulldozing, and he saved it. He now lives there and presents art exhibits. A gracious and tireless host, I think he would've put us all up for the night if we'd asked. Many parts of the church are in good shape after Pedro's study and guesswork.

He now lives there and presents art exhibits. A gracious and tireless host, I think he would've put us all up for the night if we'd asked. Many parts of the church are in good shape after Pedro's study and guesswork. The interior courtyard is made up of a well-preserved Romanesque apse and, to the side of it, a Gothic funerary chapel with many elaborate niches and an unusual five-pointed star.

The interior courtyard is made up of a well-preserved Romanesque apse and, to the side of it, a Gothic funerary chapel with many elaborate niches and an unusual five-pointed star.

Outside, a ghostly Christ monogram that was obviously and idiosyncratically carved after everything else was in place graces the weathered Romanesque entrance.

Outside, a ghostly Christ monogram that was obviously and idiosyncratically carved after everything else was in place graces the weathered Romanesque entrance.

A garden trellis is supported by sirens, saints, and serpents in the vivid column capitals.

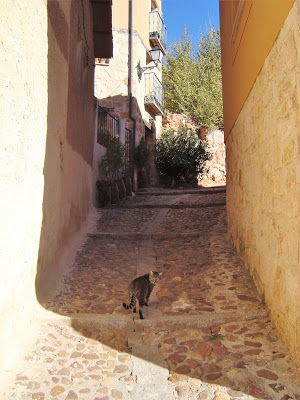

A garden trellis is supported by sirens, saints, and serpents in the vivid column capitals. This cat knows the best spots in photogenic Ayllón. After the wonders of San Juan, it was finally time for lunch. We ate a lovely Segovian meal of bean stew, lamb chops, potatoes fried in olive oil, a piquillo pepper, and a millefeuille-type pastry for dessert. I was suffering through my first cold of the season and would gladly have headed back to Madrid to sleep a long siesta in my comfy hotel room, but no, the wonders of the province of Segovia wait for no schoolyard disease. It was time to move on to Maderuelo, which will make up the epic grand finale post, coming soon. For a sneak peek, check out the Arteguías website.

This cat knows the best spots in photogenic Ayllón. After the wonders of San Juan, it was finally time for lunch. We ate a lovely Segovian meal of bean stew, lamb chops, potatoes fried in olive oil, a piquillo pepper, and a millefeuille-type pastry for dessert. I was suffering through my first cold of the season and would gladly have headed back to Madrid to sleep a long siesta in my comfy hotel room, but no, the wonders of the province of Segovia wait for no schoolyard disease. It was time to move on to Maderuelo, which will make up the epic grand finale post, coming soon. For a sneak peek, check out the Arteguías website.

Published on January 01, 2018 00:30

December 18, 2017

Happy Holidays! Felices Fiestas!

Happy holidays from Spain! For this special holiday blog, I'm giving my faithful readers exactly what you want: pictures of a fantastic castle. Minimal explanation. These are my snaps from my trip to Ponferrada earlier this month. Enjoy!

Happy holidays from Spain! For this special holiday blog, I'm giving my faithful readers exactly what you want: pictures of a fantastic castle. Minimal explanation. These are my snaps from my trip to Ponferrada earlier this month. Enjoy!

When the Pons Ferratus (iron bridge) was built here to help the pilgrims to Santiago

When the Pons Ferratus (iron bridge) was built here to help the pilgrims to Santiagoin the twelfth century, the Knights Templar settled in to protect and care for the holy travelers.

Most of the castle we see today was built during the time of Isabel and Fernando.

Most of the castle we see today was built during the time of Isabel and Fernando.

The town built up around the castle during a period of neglect.

The town built up around the castle during a period of neglect.

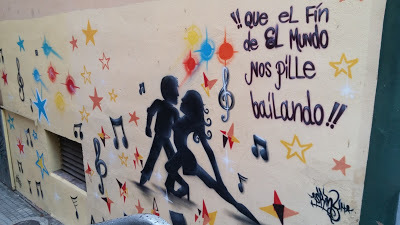

Let the end of the world find us dancing!

Let the end of the world find us dancing!  How pedestrians manage the steep hills in Ponferrada.

How pedestrians manage the steep hills in Ponferrada.  Knight Templar monument

Knight Templar monument  Caldo berciano: What they eat in Ponferrada. Yum!

Caldo berciano: What they eat in Ponferrada. Yum!  Your most trusted source for holiday gift-giving recommends

Seven Noble Knights

.

Your most trusted source for holiday gift-giving recommends

Seven Noble Knights

.

Published on December 18, 2017 00:30

December 15, 2017

Love or Money?

At the risk of obviousness, I love Spain.

At the risk of obviousness, I love Spain.I've loved Spain with blind faith since I first heard about its existence when I was about eleven years old. People have been telling me lately how hard it must be, away from home during the holidays. I've nodded and smiled, only to realize later that they were talking about me.

I can't understand why anyone would not love Spain.

I can't understand why anyone would not love Spain.Photo 2005 Jessica KnaussNo, I don't feel as if I'm away from home. If we must pathologize my experience, I've come up with the term nationality dysphoria, which is a form of psychological suffering on its way to being diagnosable, but I prefer to think of it as one of my defining characteristics rather than a disease. If you asked any one of my friends or family members to describe me, their first sentence would be, "She loves Spain."

Now that I'm here, what would it take to get me to leave? I underwent just such a test of my love and loyalty this past week. I'm exhausted!

A company I worked for in Massachusetts (one of my favorite places in the United States) had been trying to contact me about a freelance job. I welcomed this idea, because in order to live in Zamora, I teach English on a part-time basis. It pays enough to live frugally, but if I want to have money left over at the end of the year to pay student loans or buy a ticket back to the United States (that part's iffy), I have to maintain a healthy schedule of freelance editing.

The company had some trouble getting in touch with me because this came about when I was traveling in Ponferrada without much internet. We finally set up a time for a call via Google Voice on Monday afternoon. I should've suspected it was a big deal when they insisted on the phone call. Most of my freelance work never leaves the realm of email.

My favorite historical figures call me to Spain.

My favorite historical figures call me to Spain.Photo 2016 Stanley Coombs Nothing could've prepared me for what happened. I had my notebook next to the computer to write down the specifics, and it only has one line of notes before all hell broke loose in my brain. A huge editorial project in Spanish packed into three months for one of the most famous publishers, I would have to live in Massachusetts while I worked on it.

But... I live in Spain...?

As we kept talking, the offer took on epic proportions.

* A round-trip ticket.

* A rent-free apartment equipped with ways to eat frugally.

* More pay than I've ever earned in a year as a freelance editor, and much more than I make as a part-time teacher assistant, for three months' work.

That quantity of money wouldn't seem like much to some, but it would offer me some exciting possibilities.

It turned my head. I felt I'd only ever seen job offers like this in movies before. However, inconveniences included no health insurance and no transportation allowance. I would have to give notice at school and my gorgeous apartment and be on a flight by Christmas Day at the latest. (This kind of last-minute scramble is routine in this industry.)

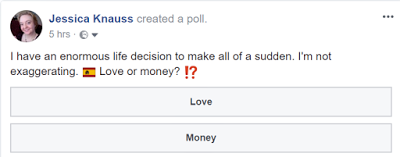

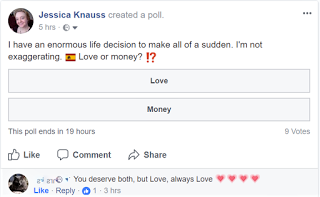

I requested twenty-four hours to decide, and put up the twenty-four-hour Facebook poll at the top of this post. The poll is highly simplified, but that was what it boiled down to for me: Love = staying in Spain, Money = leaving immediately for three months. I wanted people's gut reactions, and I got them. I was impressed, but not surprised, when Love became the favorite from the start.

I also got advice from a few people whose opinions I trust. In my shoes, they would go for the money. In my circles, money is rarer than love and you must take it when and where you find it. And, after all, I've already experienced true love, the kind you always hear about and never think is real. How greedy would I be to demand yet more love now that my sweet Stanley is gone?

I also got advice from a few people whose opinions I trust. In my shoes, they would go for the money. In my circles, money is rarer than love and you must take it when and where you find it. And, after all, I've already experienced true love, the kind you always hear about and never think is real. How greedy would I be to demand yet more love now that my sweet Stanley is gone?I went to bed thinking that in the morning, I was probably going to pack my winter clothes to head to Massachusetts. The English idiom "sleeping on it" is "consulting with the pillow" in Spanish. My Spanish pillow did a lot of convincing, because I woke up in the opposite frame of mind.

I got up and emailed to politely decline.

I got up and emailed to politely decline.With the time difference, the company wouldn't read the email for several more hours, but I felt better instantly. With that strange interlude over, I had an unusual day at school that required every ounce of extroverted energy I'd stored up over the last six months.

I was emotionally exhausted to the point of physical symptoms when I received a counteroffer.

The old offer still stood, with its plane fare and its quick time frame, but the new offer added:

* A generous food allowance.

* Even more salary!

* I would be picked up from the airport.

* I would work with people I enjoyed, as well as a new international cadre of brilliant experts.

* I would be a train ride away from all the wonders and friends of Boston.

I started thinking I would be crazy not to accept. As this blog post admits, I may just be a little crazy. Add nationality dysphoria to my normal, earth-shattering grief, and we can conclude that the only reason I'm not a complete basket case is that I'm successfully treating the symptoms of my pathology by living in Spain. I've also had some wonderful help with my grief.

I researched the details of what it would take for me to accept the offer. Sure, there were a few problems, but they all had solutions. Then the Facebook poll ended, with Love the clear winner. Why wasn't I as clear about it as my friends?

I researched the details of what it would take for me to accept the offer. Sure, there were a few problems, but they all had solutions. Then the Facebook poll ended, with Love the clear winner. Why wasn't I as clear about it as my friends?I had a coffee date that afternoon with my Zamora-native friend. It turned out that such an activity involves viewing the colorful sunset and the flight of the storks at the castle as well as a nice little walk past innumerable medieval and Renaissance architecture masterpieces that exert a physical pull on me to have tea in a cozy jazz cafe.

The storks just keep coming at Zamora Castle. (Not a photo from the coffee date.) I explained the extraordinary job offer to my friend, and he was impressed. "You must be really good."

The storks just keep coming at Zamora Castle. (Not a photo from the coffee date.) I explained the extraordinary job offer to my friend, and he was impressed. "You must be really good.""Of course, I'm the best. Didn't you know?" I replied with a sense of humor I'm not sure anyone understands but me.

All the beauty of Zamora had come out to meet me that afternoon. I savored the signature bergamot essence of Earl Grey tea in a jazz cafe in the small, unique city of my lifelong dream. My life since my true love died has dipped frequently into unbearable, but here and now, I can reach out and touch happiness, if only for the briefest moments.

"Spain will be here when you come back," my friend said. "It's not going anywhere."

It was true, but I wasn't convinced. Sure, I would have enough savings to come back in the springtime and resume everything but work at school, which I assumed wouldn't take me back after such a sudden departure. But once I was in Massachusetts, the paperwork alone would be daunting. Doubts surrounded the idea in my mind.

Some of the greatest moments of my life have happened in Spain. My Zamoran friend and I stopped at the supermarket (full of Spanish food!! I'll have to write a separate post about this aspect of life.) before heading to our separate homes, and we sang a few lines from Manolo García songs in the middle of the street. This is not something that ever happens in the United States. If he was rooting for me to take the job, he was going about it all wrong.

Some of the greatest moments of my life have happened in Spain. My Zamoran friend and I stopped at the supermarket (full of Spanish food!! I'll have to write a separate post about this aspect of life.) before heading to our separate homes, and we sang a few lines from Manolo García songs in the middle of the street. This is not something that ever happens in the United States. If he was rooting for me to take the job, he was going about it all wrong.I got home, made a Spanish-style light dinner, watched some of my favorite TV in the world, and then called up an old friend. She asked me different questions than all the other wise advisors I'd called upon so far and helped me unpack what felt wrong about the "it'll be here when you come back" argument.

Her question was: Would I have left Stanley for three months to be with a rich man?

When I recovered from the copious tears that sprang up at the thought, I choked out, "Never." No question. No argument. Everyone pack up and go home.

Photo 2005 Jessica Knauss Maybe no one else would see it this way, and maybe it's not fair to focus so much of the meaning of life on any one thing, especially a country, but this is an accurate reflection of my psychological landscape. At a deep level, I questioned whether Spain would ever take me back after such a betrayal. Perhaps the country of my birth would latch onto me and never let go. It was as if Spain was testing my loyalty and asking me to define what's most important. I couldn't disappoint the surviving love of my life, even if it will never give me words of approval because it has no lips or vocal cords.

Photo 2005 Jessica Knauss Maybe no one else would see it this way, and maybe it's not fair to focus so much of the meaning of life on any one thing, especially a country, but this is an accurate reflection of my psychological landscape. At a deep level, I questioned whether Spain would ever take me back after such a betrayal. Perhaps the country of my birth would latch onto me and never let go. It was as if Spain was testing my loyalty and asking me to define what's most important. I couldn't disappoint the surviving love of my life, even if it will never give me words of approval because it has no lips or vocal cords.I suppose everyone has their price, but the offer didn't quite meet mine.

Listen up, Spain! I passed the test. I'm staying as long as you'll let me. Send money now. Lots of money!

Published on December 15, 2017 03:22

December 3, 2017

Segovia's Medieval Treasures: The Church of the Nativity of Santa Maria de la Riaza

A monk strains to support an arch in the Church of the Nativity.

A monk strains to support an arch in the Church of the Nativity.All photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss. How to describe the company Arteguías? As the living, breathing representation of the contents of my head, perhaps. Or maybe by telling you that if it didn't exist already, it would be the company I would dream of creating.

Arteguías is a Spanish endeavor dedicated to medieval art. They publish books and present lectures on art history, make architectural models, and conduct minutely detailed guided tours of sites no other tourism company would even know about, much less consider visiting.

Looking toward the foot of the church.

Looking toward the foot of the church.Note the amazing ceiling and the baptismal font at back. I first stumbled onto Arteguías a few years ago, when my husband and I were as far from being able to go to Spain as we ever would be. Someday, someday... A few weeks after my arrival this year, I remembered my long-ago wishes and looked Arteguías up to find that they were soon going to give exactly the kind of tour I would like: medieval villages in the province of Segovia. I've been to the impressive city of Segovia many times, and the first time was during my college studies. Looking out the window of those tour buses, even though I thoroughly enjoyed the sites where they took us, I just knew they were skipping over the disregarded corners full of surprising cultural artifacts I would love the most.

Everyone on this tour was almost as excited as I was! I took the medieval villages of Segovia tour and boy, was I right. I'd been missing out hugely. Thank goodness for Arteguías, the only company willing to show me what I want to see in exactly the level of detail I demand!

Everyone on this tour was almost as excited as I was! I took the medieval villages of Segovia tour and boy, was I right. I'd been missing out hugely. Thank goodness for Arteguías, the only company willing to show me what I want to see in exactly the level of detail I demand!You, dear blog reader, are lucky because I'm going to share the best parts of that trip with you, and you don't have to spend money on travel, or a hotel in Madrid, or anything.

Our first stop was at Santa Maria de la Riaza to see its Church of the Nativity. Like many Spanish monuments, this one is on a hill, and as you drive up, it looms over you impressively. Like many medieval buildings in the province of Segovia, it's from the late Romanesque period, because during earlier medieval times, Segovia was too unstable of a border territory to construct lasting buildings of any kind.

Our first stop was at Santa Maria de la Riaza to see its Church of the Nativity. Like many Spanish monuments, this one is on a hill, and as you drive up, it looms over you impressively. Like many medieval buildings in the province of Segovia, it's from the late Romanesque period, because during earlier medieval times, Segovia was too unstable of a border territory to construct lasting buildings of any kind.The distinctive bell gable is a Baroque addition. That's all we have to say about that. The Baroque period has its place, but not on this tour.

The Romanesque part of the building still has impressive dimensions and must've drawn a congregation from many surrounding towns. The original building had a characteristic semicircular apse, which was covered up by the cross-shaped sacristy at a later date.

The gorgeous pillared arcade is all original and unique. Normally, such an arcade would be achieved with columns, but here, they didn't have any Roman monuments to steal from, so they made sturdy pillars instead. This is the largest and best preserved example of such a construction. There used to be ten windows, five on each side of the doorway, but the last two were filled in, upsetting the symmetry.

The gorgeous pillared arcade is all original and unique. Normally, such an arcade would be achieved with columns, but here, they didn't have any Roman monuments to steal from, so they made sturdy pillars instead. This is the largest and best preserved example of such a construction. There used to be ten windows, five on each side of the doorway, but the last two were filled in, upsetting the symmetry. Most of the corbels are basic, but there are a few mysterious human figures among them.

Most of the corbels are basic, but there are a few mysterious human figures among them.

The main entrance has ten corbels and a semicircular archway with five layers of different abstract designs, such as spheres (not to be confused with late Gothic Isabelline ball decor), flowers, and zigzags. The rich yellow stone takes on many blush tones here, adding to the loveliness.

The main entrance has ten corbels and a semicircular archway with five layers of different abstract designs, such as spheres (not to be confused with late Gothic Isabelline ball decor), flowers, and zigzags. The rich yellow stone takes on many blush tones here, adding to the loveliness.

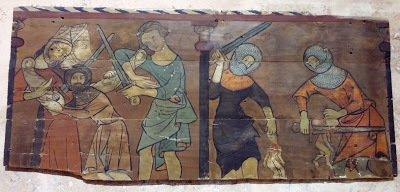

Its four column capitals merited an extended discussion in spite of their poor state of preservation. They represent lions (symbol of Christ), a couple of angels, leaves and pine cones, and people fighting.

Its four column capitals merited an extended discussion in spite of their poor state of preservation. They represent lions (symbol of Christ), a couple of angels, leaves and pine cones, and people fighting. The angels don't seem to be typical beatific types. Their facial expressions are lost to us, but the positions of their bodies indicate strong emotional states. Our guide, David, said the seated one looked miffed about something, and I had to agree.

The angels don't seem to be typical beatific types. Their facial expressions are lost to us, but the positions of their bodies indicate strong emotional states. Our guide, David, said the seated one looked miffed about something, and I had to agree. On the other side, the fighters illustrate the starting hand-fighting stance when this church was first built. The contenders had to place their feet side by side and clasp hands as if about to armwrestle, with the other arm around their opponent's neck and their foreheads touching or at least very close. The only reason I can tell you this is that David demonstrated with his assistant. These fighting scenes are so common in Segovian architecture of this period, he wanted to be sure we had the cultural context to recognize them throughout the day. It was quite a show, the stylized medieval aggression in front of that lovely archway.

On the other side, the fighters illustrate the starting hand-fighting stance when this church was first built. The contenders had to place their feet side by side and clasp hands as if about to armwrestle, with the other arm around their opponent's neck and their foreheads touching or at least very close. The only reason I can tell you this is that David demonstrated with his assistant. These fighting scenes are so common in Segovian architecture of this period, he wanted to be sure we had the cultural context to recognize them throughout the day. It was quite a show, the stylized medieval aggression in front of that lovely archway. On the other side of the fighters, a human figure appears to be carrying something, but we can only guess what. Someone on a previous tour observed that since he's next to the fighters, he's probably lifting weights in preparation for sporting combat. It makes sense. What do you think?

On the other side of the fighters, a human figure appears to be carrying something, but we can only guess what. Someone on a previous tour observed that since he's next to the fighters, he's probably lifting weights in preparation for sporting combat. It makes sense. What do you think? Inside, the main altar harbors a harmonious Virgin and Child image, transitional between Romanesque and Gothic styles, from the thirteenth century. She's surrounded by a Gothic altarpiece made up of many different scenes. You could've fooled me into thinking these were the national treasures we'd come to see, but when someone asked about them, David assured us they weren't worth a second glance. Many of these had been retouched in modern times, he added. Then I knew exactly where we stood. Our guide's tastes were well defined and hard to argue with.

Inside, the main altar harbors a harmonious Virgin and Child image, transitional between Romanesque and Gothic styles, from the thirteenth century. She's surrounded by a Gothic altarpiece made up of many different scenes. You could've fooled me into thinking these were the national treasures we'd come to see, but when someone asked about them, David assured us they weren't worth a second glance. Many of these had been retouched in modern times, he added. Then I knew exactly where we stood. Our guide's tastes were well defined and hard to argue with. All the wooden planks are meant to be "read" from right to left.

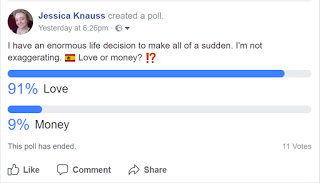

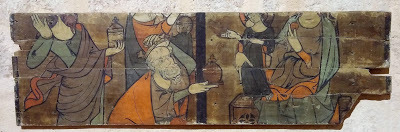

All the wooden planks are meant to be "read" from right to left.This one shows uncertain Biblical scenes. What had we come to see? These wooden planks, recovered in recent times from where they were languishing in storage and deteriorating, neglected because of changing senses of style and the modern-times superiority complex that seems to have prevailed from the Classical era until the at least the nineteenth century. David asked us to imagine what it would be like to live in a world in which these pieces of art, which we value so highly now, had always been respected and taken care of.

This fragment probably once showed a spectacular Crucifixion. The style of these paintings is linear Gothic, so called because of the cartoon-like black outlines and lack of depth. Personally, I don't need depth perspective in my paintings to arrive at depth of meaning and heights of artistic achievement. Neither did our guide, who explained the paintings to us for about 45 minutes! It was worth every second.

This fragment probably once showed a spectacular Crucifixion. The style of these paintings is linear Gothic, so called because of the cartoon-like black outlines and lack of depth. Personally, I don't need depth perspective in my paintings to arrive at depth of meaning and heights of artistic achievement. Neither did our guide, who explained the paintings to us for about 45 minutes! It was worth every second. Here we see the slaughter of the innocents, made all the more emotionally evocative because the sharp swords are so enormous in comparison to the babies. I love the colors and the facial expressions, which are reserved but clear. I dare say they reflect Castilian mannerisms. The mothers' struggle in the face of events the viewer knows to be inevitable looks especially dynamic.

Here we see the slaughter of the innocents, made all the more emotionally evocative because the sharp swords are so enormous in comparison to the babies. I love the colors and the facial expressions, which are reserved but clear. I dare say they reflect Castilian mannerisms. The mothers' struggle in the face of events the viewer knows to be inevitable looks especially dynamic. Christ, with the gold and orange nimbus, is brought before Pilate on the right and whipped by Roman guards on the left. The resignation on Christ's face turns into a sorrowful pain it would've been hard not to sympathize with.

Christ, with the gold and orange nimbus, is brought before Pilate on the right and whipped by Roman guards on the left. The resignation on Christ's face turns into a sorrowful pain it would've been hard not to sympathize with. Here, Judas kisses Jesus and the guards are ready to move in. Then, Judas hangs himself and a devil carries his soul away in a graphic depiction of his spiritual fate.

Here, Judas kisses Jesus and the guards are ready to move in. Then, Judas hangs himself and a devil carries his soul away in a graphic depiction of his spiritual fate. Christ in Majesty flanked by Mark and Luke, as demonstrated with their lion and ox symbols.

Christ in Majesty flanked by Mark and Luke, as demonstrated with their lion and ox symbols. Part of a beautifully composed Epiphany scene. Before the iconography began showing the Magi or Three Wise Men as being from three different ethnic backgrounds, they represented the three ages. The oldest, with a white beard, always comes first because he's the wisest. Here we get to see his face because he's kneeling to present his gift of gold to Mary and Jesus. I love the detail of doffing his crown. Behind him, the middle-aged man with a brown beard and the young man with no beard are missing their heads.

Part of a beautifully composed Epiphany scene. Before the iconography began showing the Magi or Three Wise Men as being from three different ethnic backgrounds, they represented the three ages. The oldest, with a white beard, always comes first because he's the wisest. Here we get to see his face because he's kneeling to present his gift of gold to Mary and Jesus. I love the detail of doffing his crown. Behind him, the middle-aged man with a brown beard and the young man with no beard are missing their heads. This fragment is probably the entrance into Jerusalem, with children laying out carpets for the "royal" arrival.

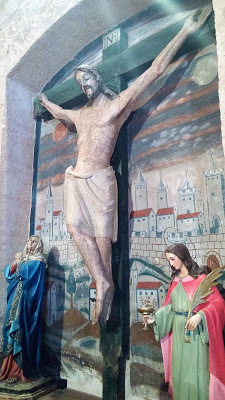

This fragment is probably the entrance into Jerusalem, with children laying out carpets for the "royal" arrival. There was still more to see. This Crucifixion is transitional between Romanesque and Gothic. When we see these artistic examples, it's like finding "the missing link." The lack of physiological detail, the long modesty panel, and the serene facial expression are Romanesque. The crossed feet, the Y shape of his arms, and the mild tilt of his head are the beginnings of the Gothic style.

There was still more to see. This Crucifixion is transitional between Romanesque and Gothic. When we see these artistic examples, it's like finding "the missing link." The lack of physiological detail, the long modesty panel, and the serene facial expression are Romanesque. The crossed feet, the Y shape of his arms, and the mild tilt of his head are the beginnings of the Gothic style. Last but not least, we studied this baptismal font. It's made from a single block of stone and is probably much older than the church. Its arches display strong Visigothic influence, and its shape also tells a story.

Last but not least, we studied this baptismal font. It's made from a single block of stone and is probably much older than the church. Its arches display strong Visigothic influence, and its shape also tells a story. David lifts an imaginary child by the

David lifts an imaginary child by the armpits into the baptismal font. According to our knowledgeable, affable, and entertaining guide, in the beginning of the Christian Church, baptism was always by immersion. The sacrament would've been given to children between three and five years old, so the font had to be big enough for the priest to take the child by the armpits and submerge him or her to the neck. The water would've been warmed whenever possible. The shape of baptismal fonts changed as their function changed. First, they became more goblet-shaped because they started immersing children at a younger age, cradling them and dipping them sideways, again leaving the head dry. You wouldn't need nearly as much warm water. Immersion got less and less popular as time wore on, so all a priest needs now is a bowl of consecrated water to pour or smudge on the child's forehead.

Armed with more new knowledge than I ever expected so early in the day, we were then off to see the medieval treasures of Ayllón.

Arteguías put a little "chronicle" of the tour on their webpage. I show up in at least two of the photos! Visit this blog in the coming weeks for more of my take on the wonders of the day.

Published on December 03, 2017 23:32

November 27, 2017

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: San Pedro de la Nave, Part III: Welcome In!

San Pedro de la Nave.

San Pedro de la Nave. All photos in this post by Jessica Knauss 2017. From afar, it's an unassuming building, and if you notice it at all, you might wonder why it's been set a little apart from the town of El Campillo. As you get closer, you see that this is not the same brickwork as the rest of the town. This is San Pedro de la Nave!

Even when it was built, the stones were extraordinary. They aren't local stones, meaning this building was costly to put together. In this picture, along the top left eave, you can see corbels placed there in Romanesque times (the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries), when the church was already hundreds of years old and in need of repair.

Even when it was built, the stones were extraordinary. They aren't local stones, meaning this building was costly to put together. In this picture, along the top left eave, you can see corbels placed there in Romanesque times (the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries), when the church was already hundreds of years old and in need of repair. The first impression of the inside is of warmth, in the golden color of the stone (which never had colored paint, as near as anyone can tell), and in the way the multiple horseshoe arches embrace your view. San Pedro's floor plan is a Latin cross, like a plus sign, and the spaces are highly compartmentalized, with little communication between the main nave and side apses. We're looking toward the main chapel here, and from this spot, there's no indication of anything beyond the main tunnel. The lateral areas could have been sacristies, chapter houses, or cells where monks lived. Yes, in those tiny spaces. (Find pictures in previous posts.)

The first impression of the inside is of warmth, in the golden color of the stone (which never had colored paint, as near as anyone can tell), and in the way the multiple horseshoe arches embrace your view. San Pedro's floor plan is a Latin cross, like a plus sign, and the spaces are highly compartmentalized, with little communication between the main nave and side apses. We're looking toward the main chapel here, and from this spot, there's no indication of anything beyond the main tunnel. The lateral areas could have been sacristies, chapter houses, or cells where monks lived. Yes, in those tiny spaces. (Find pictures in previous posts.) Looking back toward the entrance, you can appreciate the way the light illuminated the main altar on sunny days and the wooden ceiling, a practical solution to unstable Visigothic vaulting. The original vaulted ceilings are thought to have collapsed not long after they were built, and would've been replaced with a wooden ceiling much like the one we see today.

Looking back toward the entrance, you can appreciate the way the light illuminated the main altar on sunny days and the wooden ceiling, a practical solution to unstable Visigothic vaulting. The original vaulted ceilings are thought to have collapsed not long after they were built, and would've been replaced with a wooden ceiling much like the one we see today. Above, you can see that the central dome is made of bricks. The 1930s restorers wanted to differentiate their work from the stone that had survived so many centuries.

Above, you can see that the central dome is made of bricks. The 1930s restorers wanted to differentiate their work from the stone that had survived so many centuries.Glancing to the sides, you begin to appreciate the work of two different artists, one who tended toward the Classical and one with a more progressive Visigothic style.

Electric lighting was added recently. The blackness near the floor is the result of fires that were lit for lighting and warmth during San Pedro's long period of obscurity.

Electric lighting was added recently. The blackness near the floor is the result of fires that were lit for lighting and warmth during San Pedro's long period of obscurity.  The first artist was "old-fashioned," meaning that he took his inspiration from the sculptors who had gone directly before him, and limited his repertoire to plants and more abstract motifs that are highly symbolic of the church's relationship with churchgoers. The second sculptor is responsible for four of the column capitals, which have human and animal figures as well as symbolic vegetable motifs. Both artists were influenced by Byzantine art and had probably seen an illustrated copy of a Beatus of Liébana manuscript.

The first artist was "old-fashioned," meaning that he took his inspiration from the sculptors who had gone directly before him, and limited his repertoire to plants and more abstract motifs that are highly symbolic of the church's relationship with churchgoers. The second sculptor is responsible for four of the column capitals, which have human and animal figures as well as symbolic vegetable motifs. Both artists were influenced by Byzantine art and had probably seen an illustrated copy of a Beatus of Liébana manuscript. One of the biggest surprises about the columns is that they aren't structurally necessary: they don't support anything. The arches are supported in the walls. What compelled someone to put superfluous columns in such an otherwise austere space? Looking closer, we sense a highly didactic function.

One of the biggest surprises about the columns is that they aren't structurally necessary: they don't support anything. The arches are supported in the walls. What compelled someone to put superfluous columns in such an otherwise austere space? Looking closer, we sense a highly didactic function. Here, on the first column near the door on the right, we see the story of Abraham sacrificing Isaac. God's hand appears out of a cloud in the sky on the left to stop him, and the fat ram, the replacement sacrifice, appears on the right between skinny bushes. The altar is labeled as such—ALTARE—and is complete with tinder for burning the offering. A legend above the scene describes it just in case the meaning slipped the monks' minds. No detail is left out.

Here, on the first column near the door on the right, we see the story of Abraham sacrificing Isaac. God's hand appears out of a cloud in the sky on the left to stop him, and the fat ram, the replacement sacrifice, appears on the right between skinny bushes. The altar is labeled as such—ALTARE—and is complete with tinder for burning the offering. A legend above the scene describes it just in case the meaning slipped the monks' minds. No detail is left out.This is more than an important Bible story. The priests could've used this column to teach (and to remind themselves) of the way God sacrificed his son, Jesus, who also rose again from the sacrificial altar to save humankind.

The symbolism doesn't stop there. Above the capital, the cyma (capital-topper, basically) is decorated with bunches of grapes and long-necked birds. The grapes are a nod to consecrated wine—the blood of Christ—and the birds represent the human soul. They gnaw on the vines to show the human soul nourished by the blood of Christ.

San Pedro de la Nave is already extraordinary, and now you're telling me it harbors six imaginatively sculpted, unique column capitals that let us see into the Visigothic worldview? There are no words for this.

On the side, the capital shows St. Peter, the foundation of the Christian church, holding a book labeled as such—LIBER—and a cross to remind the viewer of his martyrdom.

On the side, the capital shows St. Peter, the foundation of the Christian church, holding a book labeled as such—LIBER—and a cross to remind the viewer of his martyrdom. The other side shows St. Paul, the first great traveler and proselytizer of the Christian world. He holds a book in the form of a scroll and his raised hand shows that he was a great teacher. The cyma extends back along the corner of the wall significantly, repeating its birds and vines, souls and blood, as needed.

The other side shows St. Paul, the first great traveler and proselytizer of the Christian world. He holds a book in the form of a scroll and his raised hand shows that he was a great teacher. The cyma extends back along the corner of the wall significantly, repeating its birds and vines, souls and blood, as needed. Facing Abraham and Isaac, another decorative column teaches with a different story.

Facing Abraham and Isaac, another decorative column teaches with a different story.  The prophet Daniel throws his hands up in prayer in the middle of the lions in the den, but is miraculously untouched by them. Because of the Latin translation of the den as LACUM (lake), Daniel's story is not only another reference to Christ's Resurrection (both were saved from certain death—it's a metaphor, go with it), but also to the sacrament of baptism. Yes, here, Daniel's feet are submerged as in early baptism, and rather than eating him, the lions lap at the lake's water. Daniel's robes echo the ripples in the lake, and the purposefully imperfect symmetry of the space makes it, to me, an even higher artistic achievement.

The prophet Daniel throws his hands up in prayer in the middle of the lions in the den, but is miraculously untouched by them. Because of the Latin translation of the den as LACUM (lake), Daniel's story is not only another reference to Christ's Resurrection (both were saved from certain death—it's a metaphor, go with it), but also to the sacrament of baptism. Yes, here, Daniel's feet are submerged as in early baptism, and rather than eating him, the lions lap at the lake's water. Daniel's robes echo the ripples in the lake, and the purposefully imperfect symmetry of the space makes it, to me, an even higher artistic achievement.Here, the cyma features birds more prominently, and each one picks directly at the grapes.

The left side shows the apostle Thomas, clearly labeled and holding a book that declares ENMANUEL ("God with us" according the King James Version).

The left side shows the apostle Thomas, clearly labeled and holding a book that declares ENMANUEL ("God with us" according the King James Version). Philip appears on the right side, holding over his head what's been described as a crown topped with a cross and fleurs de lis. The curls on the sides make it look like a ship to me.

Philip appears on the right side, holding over his head what's been described as a crown topped with a cross and fleurs de lis. The curls on the sides make it look like a ship to me. Moving toward the altar, the two facing columns showcase elegant birds, perhaps peacocks, representing the soul in paradise. If these columns were supporting anything, it would be San Pedro de la Nave's dome, which represents heaven. Practical function and metaphor become inextricably linked when we consider that these four columns artistically represent some of the main supports of the Christian church.

Moving toward the altar, the two facing columns showcase elegant birds, perhaps peacocks, representing the soul in paradise. If these columns were supporting anything, it would be San Pedro de la Nave's dome, which represents heaven. Practical function and metaphor become inextricably linked when we consider that these four columns artistically represent some of the main supports of the Christian church. This column is the only one whose base still clearly shows its original floral designs.

This column is the only one whose base still clearly shows its original floral designs. The cymas here feature apostolic faces, bunches of grapes, and pinecones, another representation of the church's relationship with the congregation.

The cymas here feature apostolic faces, bunches of grapes, and pinecones, another representation of the church's relationship with the congregation. The sides of these columns have large, serious faces. This one has a clear reference to Roman sun worship. It was not unusual to associate Christ with the sun in early Christianity because of the sacred space it occupied the Roman mind, and also because it sets and rises again every day. It is the ultimate representation of resurrection.

The sides of these columns have large, serious faces. This one has a clear reference to Roman sun worship. It was not unusual to associate Christ with the sun in early Christianity because of the sacred space it occupied the Roman mind, and also because it sets and rises again every day. It is the ultimate representation of resurrection. This unidentified presumed apostle is topped with a unique cyma: a lamb, with obvious symbolism.

This unidentified presumed apostle is topped with a unique cyma: a lamb, with obvious symbolism. When you're inside the lateral cells, it feels as if you can spy on everything going on in the nave.

When you're inside the lateral cells, it feels as if you can spy on everything going on in the nave. And finally, we come to the main chapel. It would've been the only chapel in Visigothic times. As I mentioned in the previous post, parts of an excavated altar were reassembled to make the new altar table here. St. Peter (San Pedro) stands on a Visigothic column that was also recovered during the transfer excavations. The area is tiny and mostly closed off from the rest. Visigothic rituals were secret, not really for public consumption, so it didn't matter if the congregation could see what the priests were doing. The reduced size probably contributed to its being the best preserved part of the church.

And finally, we come to the main chapel. It would've been the only chapel in Visigothic times. As I mentioned in the previous post, parts of an excavated altar were reassembled to make the new altar table here. St. Peter (San Pedro) stands on a Visigothic column that was also recovered during the transfer excavations. The area is tiny and mostly closed off from the rest. Visigothic rituals were secret, not really for public consumption, so it didn't matter if the congregation could see what the priests were doing. The reduced size probably contributed to its being the best preserved part of the church.  It's the only area that maintains its original Visigothic vaulting.

It's the only area that maintains its original Visigothic vaulting.  Entering this space is a sacred experience, in spite of its reduced size, largely because of the decoration, which is more profuse here than anywhere else.

Entering this space is a sacred experience, in spite of its reduced size, largely because of the decoration, which is more profuse here than anywhere else. While most Spanish guides use the word "rough" to describe these works by the Classical artist, I find them delicate, precise, and harmonious.

While most Spanish guides use the word "rough" to describe these works by the Classical artist, I find them delicate, precise, and harmonious. Crosses, grapes, geometric designs, and sunbursts frame the windows and run along the walls to unify the space and please the eye even while making reference to the same foundational metaphors we've seen on the column capitals.

Crosses, grapes, geometric designs, and sunbursts frame the windows and run along the walls to unify the space and please the eye even while making reference to the same foundational metaphors we've seen on the column capitals. The columns supporting the triumphal arch are nearly identical in conception. Also the work of the Classical artist, their cymas show winding serpents (sin) with bunches of grapes (redemption). The central parts of the capitals show four empty archways, which represent the four rivers in heavenly Jerusalem and recall the four Gospels.

The columns supporting the triumphal arch are nearly identical in conception. Also the work of the Classical artist, their cymas show winding serpents (sin) with bunches of grapes (redemption). The central parts of the capitals show four empty archways, which represent the four rivers in heavenly Jerusalem and recall the four Gospels. The columns are marble and very likely taken from a Roman construction.

The columns are marble and very likely taken from a Roman construction.On my first visit to San Pedro de la Nave, I had the luxury of being able to sit in the front pew and stare at and through the triumphal arch for an indeterminate amount of time. Time had become irrelevant as I was transported more than a thousand years into the past.

The last extraordinary and mysterious item inside San Pedro is this sundial. To the left of the triumphal arch, someone has carved the names of a few months. They're not very visible in this photo, but just under the Christ monogram, it reads +JANUARIUS Et DICEMBR MAR, with many Roman numerals indicating liturgical hours in the next row, and beneath, FBRS ET NOEMBER with their numerals. The metal bar casts a shadow on the wall, and you would think the shadow would point to the month and hours corresponding to the correct time of year.

The last extraordinary and mysterious item inside San Pedro is this sundial. To the left of the triumphal arch, someone has carved the names of a few months. They're not very visible in this photo, but just under the Christ monogram, it reads +JANUARIUS Et DICEMBR MAR, with many Roman numerals indicating liturgical hours in the next row, and beneath, FBRS ET NOEMBER with their numerals. The metal bar casts a shadow on the wall, and you would think the shadow would point to the month and hours corresponding to the correct time of year.Here's where the mystery comes in: The calendar doesn't work. It's in utterly the wrong place. Scholars have wondered why the calendar was never finished. I think the carver stopped when he realized it wasn't going to work. It also occurs to me that this stone could be recycled from another site where the calendar did work as planned. It's a less simple explanation, but perhaps more likely, given early medieval people's enthusiasm for reusing and recycling any materials at hand.

I hope you found this tour of San Pedro de la Nave as dazzling as I did.

Published on November 27, 2017 00:09

November 12, 2017

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: San Pedro de la Nave, Part II: The Ricobayo Threat

The previously flooded town of San Pedro de la Nave.

The previously flooded town of San Pedro de la Nave.Photos in this post by Jessica Knauss 2017. Imagine it's 1928 and you're a newly rediscovered pre-Romanesque treasure that happens to be on the banks of the Esla River. Yes, you are San Pedro de la Nave. In spite of a cave-in and some random additions, you still preserve the extraordinary remains of Visigothic sculpture and architecture. All of a sudden, after 1300 years of existence, you find yourself in the path of a reservoir project, about to be swallowed up by the rising waters of progress.

What do you do?

The bricks look haphazard, but they aren't. Just some of the sly smarts

The bricks look haphazard, but they aren't. Just some of the sly smarts of Visigothic architecture. Note the alabaster window, a recent addition. The Church of San Pedro de la Nave started out as the most important building in its area, the center of six small towns. Although it's not mentioned specifically in the historical record until 907, it's thought that it was the monastic center where Saint Valerio lived and did his saintly work in the seventh century because he describes it as the biggest and most luxurious of his time. When the area came under Muslim control, San Pedro slipped into obscurity. It seems there was never much money to do extensive construction work, a circumstance that saved San Pedro virtually intact for us today. In 1906, Don Manuel Gómez Moreno "discovered" the church for the modern era and it was declared a national monument in 1912.

Official tour guide Eva demonstrates how the bricks are held together.

Official tour guide Eva demonstrates how the bricks are held together. They're basically stapled with wooden clamps.Those holes should be in the back. In the 1920s, engineers became interested in the area for its hydraulic power potential. They wanted to build a dam near the town of Ricobayo, which would create a reservoir in part of the Esla River, drowning all the small towns on its banks, and destroying San Pedro de la Nave. It had just come back into the spotlight and had recently gained a few defenders. Progress couldn't be stopped, however. Historical arguments could not prevent the building of the dam.

The original site of San Pedro de la Nave. Note the foundation stones. Luckily, there were enlightened people on both sides of the issue, and someone came up with the idea of moving the church, brick by brick, to a safer location. The builders of the dam paid for the move, which took two years and a lot of research, love, and guesswork. Gómez Moreno directed the project with architect Alejandro Ferrant Vázquez and the resulting monument is a lasting testament to their scholarship.

The original site of San Pedro de la Nave. Note the foundation stones. Luckily, there were enlightened people on both sides of the issue, and someone came up with the idea of moving the church, brick by brick, to a safer location. The builders of the dam paid for the move, which took two years and a lot of research, love, and guesswork. Gómez Moreno directed the project with architect Alejandro Ferrant Vázquez and the resulting monument is a lasting testament to their scholarship. This Gothic bell tower was removed from the church

This Gothic bell tower was removed from the church and is now used as part of the fencing around it. While they dismantled the church, the workers and scholars learned a lot about Visigothic building techniques. They made note of everything, and some Roman funerary stelae and fragments of an altar were found. Most of the treasures can be viewed in the Museum of Zamora, but the altar blocks were creatively rearranged in the new place to provide an altar for occasional services.

The new altar uses blocks discovered in the dismantling process.

The new altar uses blocks discovered in the dismantling process.  The stones look like you could knock

The stones look like you could knock them over with a feather, but trust me,

they aren't budging! San Pedro de la Nave is now found two kilometers from where it originally stood in exactly the same north-south orientation as before. The original area was indeed flooded, but in recent years the water level has receded to the point that we can visit the church's original site without getting wet. Organic materials have washed away, but the sturdy stone structures of the entire town remain exactly where they were originally built.

Published on November 12, 2017 23:41

October 30, 2017

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: San Pedro de la Nave, Part I - The Legend of the Saintly Ferryman and Woman

Photos in this post by Jessica Knauss 2017 San Pedro de la Nave is a singular building in the unassuming town of Campillo.

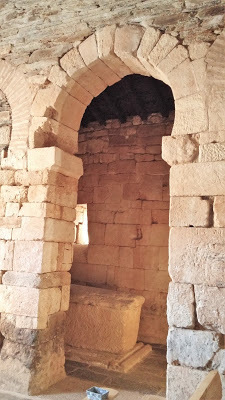

Photos in this post by Jessica Knauss 2017 San Pedro de la Nave is a singular building in the unassuming town of Campillo.If you can think of something that would make a building unique, San Pedro de la Nave has it in spades. It's permitted to hold ceremonies according to the ancient Mozarabic ritual, it preserves rare pre-Romanesque Visigothic sculpture, it was threatened with being swallowed up by a reservoir, and it was moved brick by brick to a safe location. We'll delve into all that in future posts. Now, let's start with the harrowing story people have told over the centuries to explain the presence of a simple sarcophagus that became mysterious with time.

Written in the seventeenth century, at least several centuries after the events would've taken place, the story goes: Long, long ago, a young man—let’s call him Julián—lived in a town that would later be called San Pedro de la Nave on the River Esla with his beloved mother and father. Julián was a great hunter, providing all the game his family needed and then some, and things were just dandy. One day, Julián was tracking a deer. As he closed in, the deer abruptly turned around to look at him and spoke.

Written in the seventeenth century, at least several centuries after the events would've taken place, the story goes: Long, long ago, a young man—let’s call him Julián—lived in a town that would later be called San Pedro de la Nave on the River Esla with his beloved mother and father. Julián was a great hunter, providing all the game his family needed and then some, and things were just dandy. One day, Julián was tracking a deer. As he closed in, the deer abruptly turned around to look at him and spoke.“Young Julián, you lead a good life in this fertile valley. But beware: one day, you will murder both of your beloved parents.”

Julián was shocked that the deer could speak at all. Given the extraordinary messenger, he had to believe the message. He laid down his bow and arrow right there and fled to Portugal (known as Lusitania at the time), thinking to evade the awful prophecy.

In Portugal, Julián made his fortune as a warrior. (The legend doesn’t specify what side he fought for. Whoever wrote the legend down probably had no idea who was fighting whom when Julián would’ve lived. The only thing he could be sure of was that it was on the Iberian Peninsula, so of course there was some kind of war.)

Julián was rewarded for his valor with marriage to the lovely Castilian noblewoman Basilisa. (Castile wouldn’t really have existed when Julián and Basilisa were alive, but to the seventeenth-century writer, Castile probably seemed eternal.)

Basilisa and Julián made a lovely home together, but there was another couple who wasn’t happy: Julián’s parents had been wondering where their son went and why for many years at this point. They went in search of him, and happened to find his home and bride when he was away doing important Lusitanian things.

Basilisa was a good daughter-in-law and gave Julián’s parents an unforgettable welcome. When they admitted to being exhausted from their long and worried journey, Basilisa offered them her own nuptial bed to rest in.

While her guests took their siesta, Basilisa went to church to pray. Of course that was the moment Julián came home to find two people in a bed where at most he would expect to find one: his wife, waiting for him. Julián believed Basilisa was dallying with another man, and slew both sleepers.

Basilisa walked in the door to find the horrifying sight of her mother- and father-in-law dead and explained the guests to her husband. Julián was devastated—I could’ve told him he couldn’t escape the prophecy so easily—and decided to do penance for his (totally unintended and studiously avoided) crime back in his hometown of San Pedro.

He and Basilisa set up a free service ferrying pilgrims across the River Esla so they could safely arrive at the holy sites they were aiming for. The couple did this successfully for years and earned quite the holy reputation. Finally one day, when Julián was an old man, he glimpsed someone on the opposite side of the river who needed a ferry during a severe storm.

When he made it across the dangerous river, Julián found that the pilgrim was a leper. Nonetheless, he offered the pilgrim his own bed in which to warm up and wait out the storm. Suddenly, the leper became a beautiful angel.

“Julián, your penance is complete. Your sin is redeemed. You will enjoy the rewards of Heaven. Go in peace.”

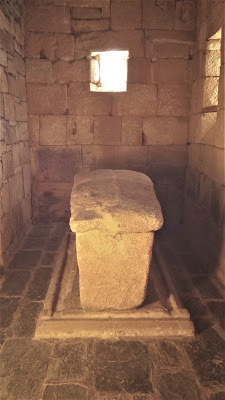

Julián and Basilisa lived out their final days feeling very blessed. That’s who’s supposed to be at rest in this tomb.

Julián and Basilisa lived out their final days feeling very blessed. That’s who’s supposed to be at rest in this tomb.Nevermind that it’s not a tomb, but a sarcophagus, where bodies were placed until such time as only bones remained. A sarcophagus is no one’s final resting place. Just try to tell that to someone writing a thousand years after this building came into being, though.

If you think this story is remarkable, just wait for the real saga of San Pedro de la Nave, in the next posts.

Published on October 30, 2017 00:30

October 23, 2017

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: San Cipriano

All photos in this post by Jessica Knauss Zamora has more than twenty Romanesque churches. This is extraordinary because, although the Romanesque style was vastly popular all over Europe in its heyday, over time people tended to dismantle the buildings from the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries in favor of Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and even more modern ways of building.

All photos in this post by Jessica Knauss Zamora has more than twenty Romanesque churches. This is extraordinary because, although the Romanesque style was vastly popular all over Europe in its heyday, over time people tended to dismantle the buildings from the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries in favor of Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and even more modern ways of building.In contrast to the Gothic style, the Romanesque might seem a little heavy, clumsy, or stiff. I'm here to say that, particularly in Zamora, the Romanesque style permitted a lot of fun artistic expression. Each of its surviving Romanesque churches has its own personality. I plan to visit them all and share the best with you here.

We'll start with San Cipriano because there's something mysteriously appealing about this church. When you come up on it from the public library or the parador nearby, it exerts a pull on you. Even the locals must feel it, because San Cipriano's plaza is a popular hangout among people of all ages. I wonder if they appreciate that this church shows up in the historical record for the first time in 1159.

We'll start with San Cipriano because there's something mysteriously appealing about this church. When you come up on it from the public library or the parador nearby, it exerts a pull on you. Even the locals must feel it, because San Cipriano's plaza is a popular hangout among people of all ages. I wonder if they appreciate that this church shows up in the historical record for the first time in 1159. Its bell tower, which used to form part of the defenses in the town wall, is pleasingly proportioned and visible from many prime spots in the city. Look for the stork nest in the corner. The stones that make up the church exterior have exquisite reddish accents, and the windows and doors display iconography worthy of any museum--and that's just the outside!

Its bell tower, which used to form part of the defenses in the town wall, is pleasingly proportioned and visible from many prime spots in the city. Look for the stork nest in the corner. The stones that make up the church exterior have exquisite reddish accents, and the windows and doors display iconography worthy of any museum--and that's just the outside! In this window, between two columns with floral capitals, two of the three Marys are portrayed next to the holy sepulcher with an angel and a sleeping solider. On the right, Abraham sacrifices Isaac. How do these themes go together? God's sparing of Isaac was interpreted during this time period as foretelling Jesus' sacrifice and resurrection. Both were placed upon a literal or metaphorical sacrificial altar, and both rose up from it again.

In this window, between two columns with floral capitals, two of the three Marys are portrayed next to the holy sepulcher with an angel and a sleeping solider. On the right, Abraham sacrifices Isaac. How do these themes go together? God's sparing of Isaac was interpreted during this time period as foretelling Jesus' sacrifice and resurrection. Both were placed upon a literal or metaphorical sacrificial altar, and both rose up from it again. Three of the church's architects had the sculptors make portraits of them so everyone would know who made this: Ildefonso, Sancho, and Raimundo. An inscription inside indicates they also made the church of San Andrés in 1093.

Three of the church's architects had the sculptors make portraits of them so everyone would know who made this: Ildefonso, Sancho, and Raimundo. An inscription inside indicates they also made the church of San Andrés in 1093. These weathered fellows have been identified as the apostles James, Thomas, Peter, and Philip.

These weathered fellows have been identified as the apostles James, Thomas, Peter, and Philip.

The southern entry has a lovely triple Romanesque archway that would be treasured anywhere else, but here is easily overlooked. Around the arch are many unique carvings from the original structure which were placed here during the 1975 retoration: an ironworker named Bermudo with memorial inscription on the left, St. Peter with his keys, a monogram of Christ, and on the right, the apocalyptic beast with seven heads.

The southern entry has a lovely triple Romanesque archway that would be treasured anywhere else, but here is easily overlooked. Around the arch are many unique carvings from the original structure which were placed here during the 1975 retoration: an ironworker named Bermudo with memorial inscription on the left, St. Peter with his keys, a monogram of Christ, and on the right, the apocalyptic beast with seven heads. A more customary theme in this region shows up on the other side of the door: Daniel in the lions' den. Daniel's story was interpreted as a parallel to the Resurrection in Visigothic times, and this is surely a carryover.

A more customary theme in this region shows up on the other side of the door: Daniel in the lions' den. Daniel's story was interpreted as a parallel to the Resurrection in Visigothic times, and this is surely a carryover. The eaves have many lovely corbels, some geometric, some abstractly floral, some monstrous, and here in the center, I think we can see a primitive Adam and Eve. Any of these could be restorations from 1975. As weathered as it is, I admire the checkerboard effect above them. It was a favorite pattern in the Zamoran Romanesque aesthetic.

The eaves have many lovely corbels, some geometric, some abstractly floral, some monstrous, and here in the center, I think we can see a primitive Adam and Eve. Any of these could be restorations from 1975. As weathered as it is, I admire the checkerboard effect above them. It was a favorite pattern in the Zamoran Romanesque aesthetic. In the interior, San Cipriano gives an impression of vastness, which was unusual for the Romanesque in general, but fairly common in the outsized style of Zamora. You can easily appreciate how it started out with three parallel apses and was cleared out to form one unified space in the thirteenth century.