Jessica Knauss's Blog, page 7

January 8, 2019

The Forgotten Royal Pantheon: Oña

Oña

OñaPhotos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss The area where my castle is, the Merindades, surprises again and again with its exceptional natural beauty and historical value. The same day we visited my castle, my friend and I returned to Burgos via Oña, a place of old glory I'd hardly ever heard about, in spite of how pertinent it turned out to be to my historical and novel-writing interests.

We pulled into a parking lot near the old train station and found a quaint place to have our midday meal before taking a personal guided tour--what a luxury! We got to ask questions about what interested us and look at all the wonders at our own pace. The drawback for this blog is that no photos were allowed. I haven't found anything usable online, either, so we'll have to make do with my exterior and cloister shots and your readerly imagination.

We pulled into a parking lot near the old train station and found a quaint place to have our midday meal before taking a personal guided tour--what a luxury! We got to ask questions about what interested us and look at all the wonders at our own pace. The drawback for this blog is that no photos were allowed. I haven't found anything usable online, either, so we'll have to make do with my exterior and cloister shots and your readerly imagination. As I mentioned in my castle post, the Merindades area was the forge of the Castilian character, the ancestral home of modern Spain. Oña in particular was staggeringly important throughout the Middle Ages, and for that reason, it's a melting pot of architectural styles that is fun to study and untangle.

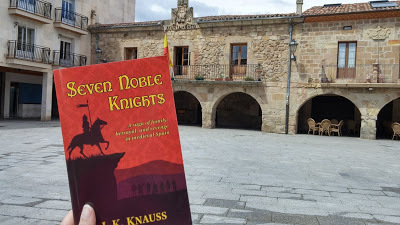

As I mentioned in my castle post, the Merindades area was the forge of the Castilian character, the ancestral home of modern Spain. Oña in particular was staggeringly important throughout the Middle Ages, and for that reason, it's a melting pot of architectural styles that is fun to study and untangle.  As readers of Seven Noble Knights will know, before Castile was a kingdom, it was a semi-independent county of León, and history honors four Counts of Castile. The third such count, Sancho García (the son of Count García of Seven Noble Knights fame) established the double monastery (both monks and nuns) at Oña in 1011 so that his daughter, Tigridia, could be the abbess. The area was particularly strategic in holding the Castilian border against half-amicable Navarrese encroachment. In 1033 it became a monks-only monastery under the Benedictine rule, and enjoyed prosperity and kept the most records of any medieval monastery in northern Spain until the State seized all Church property to balance the budget. Oña was sold off in two parcels in 1836. The area with the monks' dorms and living areas, library, and fish hatchery has since then been used as a Jesuit school, but now stands empty. We were only able to visit the sanctuary and cloister.

As readers of Seven Noble Knights will know, before Castile was a kingdom, it was a semi-independent county of León, and history honors four Counts of Castile. The third such count, Sancho García (the son of Count García of Seven Noble Knights fame) established the double monastery (both monks and nuns) at Oña in 1011 so that his daughter, Tigridia, could be the abbess. The area was particularly strategic in holding the Castilian border against half-amicable Navarrese encroachment. In 1033 it became a monks-only monastery under the Benedictine rule, and enjoyed prosperity and kept the most records of any medieval monastery in northern Spain until the State seized all Church property to balance the budget. Oña was sold off in two parcels in 1836. The area with the monks' dorms and living areas, library, and fish hatchery has since then been used as a Jesuit school, but now stands empty. We were only able to visit the sanctuary and cloister.  Looking down on the Plaza Mayor of Oña from the monastery

Looking down on the Plaza Mayor of Oña from the monastery  Our guide waits for the right moment to start our tour.

Our guide waits for the right moment to start our tour.  The bell gable was the last element to be added, in the nineteenth century,

The bell gable was the last element to be added, in the nineteenth century, after the Romanesque tower fell.

The gate was part of a defensive city wall

The gate was part of a defensive city wallerected in the fourteenth century. The statuettes are portraits of the royals buried inside. Tigridia became a saint during her time here as abbess. We admired a Baroque altar with her casket, then a recently revealed lineal Gothic mural depicting the entire life of St. Mary the Egyptian, a stunning Romanesque-Gothic transition Crucifixion surrounded by a gorgeous Flemish-Spanish fifteenth-century altar, and two Romanesque capitals up so high I couldn't tell what they represented, complete with original paint. I won't complain anymore about high-up Romanesque capitals because I'm taking a course in Romanesque symbolism. Now I know that height was just as important to Romanesque artists for looking up toward God as it was for Gothic artists. They just went about it in diametrically different ways.

The statuettes make the pantheon the first aspect the visitor encounters at the monastery. Another important resident here was Fray Pedro Ponce de León. He arrived in 1536 and took on the education of two noble children who had been deaf from birth. He is credited with creating the precursor of sign language.

The statuettes make the pantheon the first aspect the visitor encounters at the monastery. Another important resident here was Fray Pedro Ponce de León. He arrived in 1536 and took on the education of two noble children who had been deaf from birth. He is credited with creating the precursor of sign language. The door is Romanesque-Gothic transition, but the windows are fully Romanesque. After my friend and I admired a well-preserved Baroque organ and an extraordinary Gothic choir carved from walnut by the monks themselves, we got an eyeful of the main altar and the royal pantheon to either side of it.

The door is Romanesque-Gothic transition, but the windows are fully Romanesque. After my friend and I admired a well-preserved Baroque organ and an extraordinary Gothic choir carved from walnut by the monks themselves, we got an eyeful of the main altar and the royal pantheon to either side of it. The Gothic cloister The main altar consists of a tall, frothy Baroque tabernacle of gold curlicues surrounding the sixteenth-century gold, silver, and gemstone (probably glass pieces) casket of Saint Íñigo, one of the first and strictest abbots of the monastery. My friend thought we could easily buy my castle with the gold and silver in the casket alone, and he may be right.

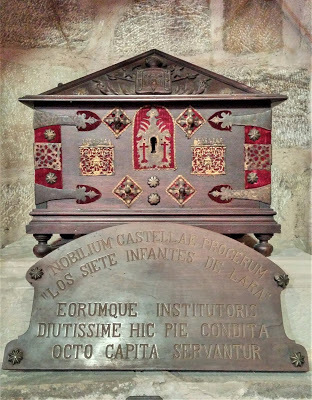

The Gothic cloister The main altar consists of a tall, frothy Baroque tabernacle of gold curlicues surrounding the sixteenth-century gold, silver, and gemstone (probably glass pieces) casket of Saint Íñigo, one of the first and strictest abbots of the monastery. My friend thought we could easily buy my castle with the gold and silver in the casket alone, and he may be right. But the pantheon is where it's at. Oña was always a place of noble burials, and they think the entryway between the gate and the door may have served as the first cemetery. The remains were transferred to the Chapel of the Virgin by order of Sancho IV (son of Alfonso X) in 1285. By the late fifteenth century, even this was deemed inadequate, and the remains were moved to flank the main altar and new tombs constructed.

But the pantheon is where it's at. Oña was always a place of noble burials, and they think the entryway between the gate and the door may have served as the first cemetery. The remains were transferred to the Chapel of the Virgin by order of Sancho IV (son of Alfonso X) in 1285. By the late fifteenth century, even this was deemed inadequate, and the remains were moved to flank the main altar and new tombs constructed. Tomb of a twelfth-century nobleman of La Bureba in the Gothic cloister The "new" royal tombs stand out because they aren't made of stone, but of walnut and boxwood. Their wooden tabernacles are smooth extensions of the Gothic traceries of the choir seating, and luxuriously carved and embossed tombs are surrounded by Flemish-Spanish paintings. On the left, four royal tombs, and on the right, four tombs of counts and other royals. The organization and setting give the impression of utmost respect if not adoration of these historical figures by the people who made the tombs. A sense of plenitude and perfection filled the area.

Tomb of a twelfth-century nobleman of La Bureba in the Gothic cloister The "new" royal tombs stand out because they aren't made of stone, but of walnut and boxwood. Their wooden tabernacles are smooth extensions of the Gothic traceries of the choir seating, and luxuriously carved and embossed tombs are surrounded by Flemish-Spanish paintings. On the left, four royal tombs, and on the right, four tombs of counts and other royals. The organization and setting give the impression of utmost respect if not adoration of these historical figures by the people who made the tombs. A sense of plenitude and perfection filled the area. The Renaissance tomb of Bishop Pedro Gonzalez Manso (d. 1539) in the cloister

The Renaissance tomb of Bishop Pedro Gonzalez Manso (d. 1539) in the cloister is backed with a Romanesque grille. On the royal side, we find the tomb of Sancho II, whose body was brought here personally by his devoted vassal, El Cid. This king was famously assassinated in Zamora in 1072. Next to Sancho II, we find Sancho III of Navarra (d. 1035), probably the most important and influential king of that small country. Next to Sancho III rests his wife and queen, Mayor. Finally, we contemplate the tomb of Prince García, son of Alfonso VII of Castile. The lad was studying at the monastery when he passed away at the age of 8.

Cloisters achieve a sense of upward pull by planting trees. The count side is full of people I want to write novels about. First, the third Count of Castile, Sancho García. As I mentioned, he's the son of Count García in Seven Noble Knights, and in 1002, Sancho defeated the mighty Almanzor (who also appears in Seven Noble Knights) at Calatañazor, as well as founding this monastery. Sancho will have a few important things to do in the sequel to Seven Noble Knights, if I ever get to write it! Next to him rests his wife, Countess Urraca.

Cloisters achieve a sense of upward pull by planting trees. The count side is full of people I want to write novels about. First, the third Count of Castile, Sancho García. As I mentioned, he's the son of Count García in Seven Noble Knights, and in 1002, Sancho defeated the mighty Almanzor (who also appears in Seven Noble Knights) at Calatañazor, as well as founding this monastery. Sancho will have a few important things to do in the sequel to Seven Noble Knights, if I ever get to write it! Next to him rests his wife, Countess Urraca. Next to his mother lies Prince García, who was the fourth and last Count of Castile. His story is part of the foundation of the Kingdom of Castile, and I've been dreaming of writing a separate novel about him. I wish I could describe how much it meant to me to be in the presence of the tombs of the people whose stories I want so much to tell.

Next to his mother lies Prince García, who was the fourth and last Count of Castile. His story is part of the foundation of the Kingdom of Castile, and I've been dreaming of writing a separate novel about him. I wish I could describe how much it meant to me to be in the presence of the tombs of the people whose stories I want so much to tell. The final tomb holds the remains of two of Sancho IV's children.

After enjoying the Gothic cloister, we found a lovely book full of photos and history at the gift stand near the exit, only to find out that the author had been our tour guide! As we headed down the steps to the tourism office to get his authorial signature, I realized my watch wasn't attached to my wrist. It's not an expensive watch, but I bought it while I was studying in Salamanca, around the time I dreamed I had an artists' colony in a Spanish castle, and it's been with me every day for thirteen years. I marveled that I should lose such an item in this historical place.

After enjoying the Gothic cloister, we found a lovely book full of photos and history at the gift stand near the exit, only to find out that the author had been our tour guide! As we headed down the steps to the tourism office to get his authorial signature, I realized my watch wasn't attached to my wrist. It's not an expensive watch, but I bought it while I was studying in Salamanca, around the time I dreamed I had an artists' colony in a Spanish castle, and it's been with me every day for thirteen years. I marveled that I should lose such an item in this historical place.  After our guide signed the book we'd just bought, he called the monastery and told my friend and me they would let us back in to look around. So we got two visits for the price of one! It was hard to look at the floor with so many medieval artistic wonders higher up. We felt strongly that we would've heard the watch hit the hard flooring throughout most of the complex. Only one place lacked the hard floor--the cloister, where the burbling fountain might also have impeded our noticing anything amiss. That's where we found it. The thirteen-year legacy of my Salamancan watch will continue, hopefully for another thirteen years or more.

After our guide signed the book we'd just bought, he called the monastery and told my friend and me they would let us back in to look around. So we got two visits for the price of one! It was hard to look at the floor with so many medieval artistic wonders higher up. We felt strongly that we would've heard the watch hit the hard flooring throughout most of the complex. Only one place lacked the hard floor--the cloister, where the burbling fountain might also have impeded our noticing anything amiss. That's where we found it. The thirteen-year legacy of my Salamancan watch will continue, hopefully for another thirteen years or more. I had the clasp tightened at a watch repair store the next day.

Published on January 08, 2019 06:36

January 5, 2019

The Castle of My Dreams

Castle and proprietor. Count on it.

Castle and proprietor. Count on it.All photos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss In January 2006, I was studying very hard in Salamanca. I was also getting to know the public face of Manolo Garcia as I'd never had the opportunity to before, and loving every new thing I learned, about both Alfonso X el Sabio and Manolo Garcia.

That month, thirteen years ago, I dreamed I lived in a large structure with many staircases and bedrooms. This wonderful dwelling was filled with ten or twelve writers and artists, focusing on their creations and feeling inspired by their distraction-free but gorgeous surroundings. One unassuming but popular guest was Manolo Garcia. He would give impromptu creativity talks in chambers where everyone sat on sumptuous pillows, but mostly he created, like all the other artists. He stopped me on a staircase to thank me for inviting him to my artistically stimulating refuge from the obligations of daily life, saying it had been the best month of his life.

That month, thirteen years ago, I dreamed I lived in a large structure with many staircases and bedrooms. This wonderful dwelling was filled with ten or twelve writers and artists, focusing on their creations and feeling inspired by their distraction-free but gorgeous surroundings. One unassuming but popular guest was Manolo Garcia. He would give impromptu creativity talks in chambers where everyone sat on sumptuous pillows, but mostly he created, like all the other artists. He stopped me on a staircase to thank me for inviting him to my artistically stimulating refuge from the obligations of daily life, saying it had been the best month of his life. Since then, I've known exactly what I will do with all the money I'll earn from bestselling books and unexpected inheritances. I'm inspired to run an artists' colony where writers and all kinds of creatives can practice their art unencumbered in a spectacular setting.

Since then, I've known exactly what I will do with all the money I'll earn from bestselling books and unexpected inheritances. I'm inspired to run an artists' colony where writers and all kinds of creatives can practice their art unencumbered in a spectacular setting. Fast forward ten years, ten of the best years of my life because they included my marriage to Stanley. Poking around on the internet one day in late 2015, I found a castle for sale. A Spanish castle for sale. The asking price was five million euros, which doesn't seem outlandish to fulfill one's cherished life dream, but was far out out of my prospects.

Fast forward ten years, ten of the best years of my life because they included my marriage to Stanley. Poking around on the internet one day in late 2015, I found a castle for sale. A Spanish castle for sale. The asking price was five million euros, which doesn't seem outlandish to fulfill one's cherished life dream, but was far out out of my prospects. I showed the listing to my soul mate and he was happy to find out it's in the same region as Frías, a gorgeous medieval wonderland we'd recently seen and where he said many times (jokingly) that we should go and live. The region is called the Merindades, and it's the hardscrabble mountain birth mother of Castile, and thus of Spain as we know it.

I showed the listing to my soul mate and he was happy to find out it's in the same region as Frías, a gorgeous medieval wonderland we'd recently seen and where he said many times (jokingly) that we should go and live. The region is called the Merindades, and it's the hardscrabble mountain birth mother of Castile, and thus of Spain as we know it. Specifically, my castle is located in Lezana de Mena. It's next door to the place where the word "Castile" was written down for the first time (that we know of). The first written notice of the castle is from 1397, and it was built a few years before that for the Angulo family, one of the important landowners in the region. The construction is solid and finished with perfection in every angle. Aside from the tower, which is the only thing visible in my photos here, it has a wall and other towers and some usable one-story buildings. It sits on 22,000 square meters of gardens with fruit trees, a stream, a little forest with three century-old oaks, and a large pond. (Perfect for rhinoceros grazing, but we'll think about that later.)

Specifically, my castle is located in Lezana de Mena. It's next door to the place where the word "Castile" was written down for the first time (that we know of). The first written notice of the castle is from 1397, and it was built a few years before that for the Angulo family, one of the important landowners in the region. The construction is solid and finished with perfection in every angle. Aside from the tower, which is the only thing visible in my photos here, it has a wall and other towers and some usable one-story buildings. It sits on 22,000 square meters of gardens with fruit trees, a stream, a little forest with three century-old oaks, and a large pond. (Perfect for rhinoceros grazing, but we'll think about that later.) The price, to me, is further justified because it boasts state-of-the-art central heating; a heated swimming pool with geothermal technology, a wave generator, and spa jets; all new plumbing; double-glazed windows; a centralized vacuum cleaning system; satellite telephone system with Wi-Fi, TV in all rooms, and motion detectors in communal areas; five open fireplaces, three of which have inserted cassettes with hot air impellers with insulated stainless steel flues; solid oak beams and stairways; floors made of oak, chestnut, and northern pine; six bed chambers with on-suite bathrooms, two with walk-in wardrobes; three powder rooms; a library; a large refectory; public rooms; a kitchen; and an elevator!

The price, to me, is further justified because it boasts state-of-the-art central heating; a heated swimming pool with geothermal technology, a wave generator, and spa jets; all new plumbing; double-glazed windows; a centralized vacuum cleaning system; satellite telephone system with Wi-Fi, TV in all rooms, and motion detectors in communal areas; five open fireplaces, three of which have inserted cassettes with hot air impellers with insulated stainless steel flues; solid oak beams and stairways; floors made of oak, chestnut, and northern pine; six bed chambers with on-suite bathrooms, two with walk-in wardrobes; three powder rooms; a library; a large refectory; public rooms; a kitchen; and an elevator! And now the asking price has been reduced to less than three million euros!

And now the asking price has been reduced to less than three million euros! This first week of January 2018, I had the chance to visit my castle for the first time, so of course I seized it! Driving north from Burgos, my friend and I were aghast at the constantly changing countryside. Just looking through the window filled me with gratitude. "If you like Castile," said my friend, "it doesn't get any more authentic than this!"

This first week of January 2018, I had the chance to visit my castle for the first time, so of course I seized it! Driving north from Burgos, my friend and I were aghast at the constantly changing countryside. Just looking through the window filled me with gratitude. "If you like Castile," said my friend, "it doesn't get any more authentic than this!" Passing by innumerable Romanesque churches and other castles I don't currently have plans to buy, weaving through the mountains, we at last came around a bend and my castle presented itself to me like a gift from Spain, the entity I've loved longest and hardest. It was apparent that the castle wasn't open to visits from tourists (But I'm not a tourist! I'm the future owner!) before we even parked.

Passing by innumerable Romanesque churches and other castles I don't currently have plans to buy, weaving through the mountains, we at last came around a bend and my castle presented itself to me like a gift from Spain, the entity I've loved longest and hardest. It was apparent that the castle wasn't open to visits from tourists (But I'm not a tourist! I'm the future owner!) before we even parked. The town surprised me with its lively atmosphere. It lacked the sense of desolation you get in a lot of towns on the Castilian plain, and felt welcoming. We had tea in the bar across from what looked like the castle's front gate, while I was champing at the bit to get outside and take photos and commune with my castle. The lady who made our tea gave us the low-down: Indeed, no one is allowed in the castle unless they intend to put their visit in a high-visibility publication or have documented ability to buy it. Even so, I didn't feel turned away. I had a strong sense of being in the right place, which is something I haven't felt in my life very often.

The town surprised me with its lively atmosphere. It lacked the sense of desolation you get in a lot of towns on the Castilian plain, and felt welcoming. We had tea in the bar across from what looked like the castle's front gate, while I was champing at the bit to get outside and take photos and commune with my castle. The lady who made our tea gave us the low-down: Indeed, no one is allowed in the castle unless they intend to put their visit in a high-visibility publication or have documented ability to buy it. Even so, I didn't feel turned away. I had a strong sense of being in the right place, which is something I haven't felt in my life very often. The castle passed into the Velasco family in the early fifteenth century, a time full of conflicts between nobles and uprisings at all levels. The Velascos had countless castles all over what is now northern Castile, claiming their territory and warning against any and all transgressions of authority. Wouldn't it be ideal to have an invasion of writers and artists in this beautiful space to encourage the sense of peace that now blankets this valley?

The castle passed into the Velasco family in the early fifteenth century, a time full of conflicts between nobles and uprisings at all levels. The Velascos had countless castles all over what is now northern Castile, claiming their territory and warning against any and all transgressions of authority. Wouldn't it be ideal to have an invasion of writers and artists in this beautiful space to encourage the sense of peace that now blankets this valley?  Generous donations graciously accepted, serious investment queries gladly entertained.

Generous donations graciously accepted, serious investment queries gladly entertained.

Published on January 05, 2019 06:15

December 29, 2018

Cantigas in the Air

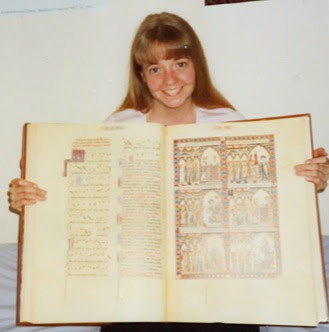

Yours truly with a facsimile of the Codice rico of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

Yours truly with a facsimile of the Codice rico of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.It's an enduring infatuation.

What a year it's been! One of the most surprising accomplishments I can count in 2018 is that I took part in my second radio interview. Dr. Debra J. Bolton interviewed me about the beloved

Cantigas de Santa Maria

for her music-filled Christmas-day broadcast. As well as introducing me and my cantigas work in a flattering fashion, Dr. Bolton managed to make my responses to her questions seem coherent even though I was suffering from the vestiges of a cold and overwhelmed with the enthusiasm of thinking about these stories and their art and music.

What a year it's been! One of the most surprising accomplishments I can count in 2018 is that I took part in my second radio interview. Dr. Debra J. Bolton interviewed me about the beloved

Cantigas de Santa Maria

for her music-filled Christmas-day broadcast. As well as introducing me and my cantigas work in a flattering fashion, Dr. Bolton managed to make my responses to her questions seem coherent even though I was suffering from the vestiges of a cold and overwhelmed with the enthusiasm of thinking about these stories and their art and music.Mostly it's a lovely show because of the variety of cantigas recordings you get to hear. I'm honored to have been a part of this celebration of multicultural wisdom and joy.

The show will be rebroadcast on December 30 at 9 a.m. United States Central Time. You can listen from anywhere via the High Plains Public Radio site.

If time zones are an issue for you like they are for me, check out the handy dandy Time Zone Converter. Tune into hppr.org at 9 a.m. on December 30 for hours of cantiga enjoyment.

Published on December 29, 2018 01:08

November 14, 2018

Galician Romanesque, or Santiago and His Pilgrimage in La Coruña

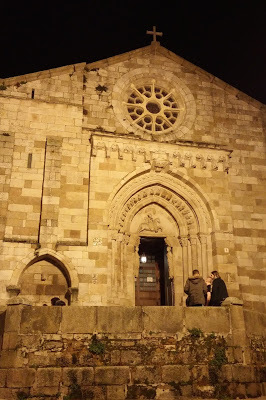

The Church of Santiago under a typically cloudy La Coruña sky

The Church of Santiago under a typically cloudy La Coruña skyAll photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss I recently had the opportunity to visit La Coruña. I faced wind and rain (What did you expect? It's the coast of Galicia.) to investigate the Romanesque style at what was, in the European Middle Ages, the edge of the known world.

While in this seaworthy and fascinating corner of Spain, I learned about a Renaissance episode that drastically affected how we can appreciate La Coruña's medieval art. In 1589, the English besieged the city as a revenge for the Invincible Armada's attack in 1588. (Sore feelings even after soundly trouncing the Spanish navy and starting a long period of historical decline? How much reinforcement do you need, England?) The soldiers of La Coruña and its local citizens turned the English away, but before the siege, the city boasted five Romanesque churches and a monastery; when it was over, only two Romanesque churches remained in the city proper. (You can guess how I feel about his instance of history obliterating history.)

While in this seaworthy and fascinating corner of Spain, I learned about a Renaissance episode that drastically affected how we can appreciate La Coruña's medieval art. In 1589, the English besieged the city as a revenge for the Invincible Armada's attack in 1588. (Sore feelings even after soundly trouncing the Spanish navy and starting a long period of historical decline? How much reinforcement do you need, England?) The soldiers of La Coruña and its local citizens turned the English away, but before the siege, the city boasted five Romanesque churches and a monastery; when it was over, only two Romanesque churches remained in the city proper. (You can guess how I feel about his instance of history obliterating history.) Santiago (Saint James the Apostle) is the oldest of the surviving church buildings, having been first constructed in the second half of the twelfth century in the same "Mateo" style as the Romanesque Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. The ground on which it stands has been hallowed for a very long time, perhaps as early as the tenth century.

Santiago (Saint James the Apostle) is the oldest of the surviving church buildings, having been first constructed in the second half of the twelfth century in the same "Mateo" style as the Romanesque Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. The ground on which it stands has been hallowed for a very long time, perhaps as early as the tenth century.This church was established as the beginning of the walking Camino (Santiago pilgrimage) for English pilgrims arriving in Galicia by sea. It was restored multiple times in the medieval era because of fire damage, which makes the structure a historical record in itself. Fortunately, the original apse area, as we see here, survived to display the particularities of Galician Romanesque for visitors today.

The outside of the apse has many delightful corbels. Here, a bearded man and a man pulling at his mouth.

The outside of the apse has many delightful corbels. Here, a bearded man and a man pulling at his mouth.  Here, many different realistic animals, a miniature bestiary.

Here, many different realistic animals, a miniature bestiary. This building embodied the bond between the medieval Church and State. As late as 1521, this church had two towers: the surviving one here (this version constructed in 1607) with the bells and clock, and a second one that held munitions, archives, and other city government items the town hall didn't have room for. For more than one hundred years from the fourteenth century, the temple also served as the city council's meeting place.

This building embodied the bond between the medieval Church and State. As late as 1521, this church had two towers: the surviving one here (this version constructed in 1607) with the bells and clock, and a second one that held munitions, archives, and other city government items the town hall didn't have room for. For more than one hundred years from the fourteenth century, the temple also served as the city council's meeting place. The shortest street in La Coruña is found between Santiago's tower and the old consulate building, which has a Renaissance coat of arms and interesting Romanesque Resurrection, both taken from other, unknown sites.

The shortest street in La Coruña is found between Santiago's tower and the old consulate building, which has a Renaissance coat of arms and interesting Romanesque Resurrection, both taken from other, unknown sites.  The first thing I noticed about this lovely north doorway is that the door itself is square, as in other churches, but the door jamb has extra symmetrical decorative elements, giving the top an indented look I found repeated in the other two Romanesque churches I saw in La Coruña. The indentations are oxen heads, which in close proximity to the Lamb of God in the archway, represent the triumph of Good over Evil. The archway is better preserved than most other areas of this church and features many attractive flowers as well as the Lamb, both much in the "Mateo" style.

The first thing I noticed about this lovely north doorway is that the door itself is square, as in other churches, but the door jamb has extra symmetrical decorative elements, giving the top an indented look I found repeated in the other two Romanesque churches I saw in La Coruña. The indentations are oxen heads, which in close proximity to the Lamb of God in the archway, represent the triumph of Good over Evil. The archway is better preserved than most other areas of this church and features many attractive flowers as well as the Lamb, both much in the "Mateo" style. The front entrance displays features from different medieval styles, as well as evidence of where the other tower used to be. The pointed main arch and rose window are from the end of the fourteenth century, but still copy the much venerated "Mateo" style. Christ shows his wounds at the arch's apex, and the interior of the arch and the rain ledge are resplendent with seated angels.

The front entrance displays features from different medieval styles, as well as evidence of where the other tower used to be. The pointed main arch and rose window are from the end of the fourteenth century, but still copy the much venerated "Mateo" style. Christ shows his wounds at the arch's apex, and the interior of the arch and the rain ledge are resplendent with seated angels. It's only natural that the church of Santiago should sport an image of that saint at its entrance. However, the vast empty space around the horseman and the modern look of his boots are sure signs that something else originally occupied the space where Santiago now gallops in search of Moors to slay. This figure is indeed later than anything else we've seen so far, from the sixteenth century. His metal sword has had time to turn green in the Galician weather, giving him a lightsaber-y pizzazz.

It's only natural that the church of Santiago should sport an image of that saint at its entrance. However, the vast empty space around the horseman and the modern look of his boots are sure signs that something else originally occupied the space where Santiago now gallops in search of Moors to slay. This figure is indeed later than anything else we've seen so far, from the sixteenth century. His metal sword has had time to turn green in the Galician weather, giving him a lightsaber-y pizzazz. A Gothic-style tomb has been cut out of the front wall.

A Gothic-style tomb has been cut out of the front wall. On this side, the magnificent although eroded column capitals show twisting dragons (the Devil), an angel, and a scene that was popular in Romanesque times, Daniel in the lions' den. Although Daniel himself is mostly missing, four lions and the figure of Habakkuk accompanied by an angel make it unmistakable.

On this side, the magnificent although eroded column capitals show twisting dragons (the Devil), an angel, and a scene that was popular in Romanesque times, Daniel in the lions' den. Although Daniel himself is mostly missing, four lions and the figure of Habakkuk accompanied by an angel make it unmistakable. The plant-themed column capitals on the other side are finished off with a story that's not often seen in Galicia, but this blog's readers have seen before, also closely associated with Daniel in the lions' den: the sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham wields a sword, which an angel takes hold of to stop him turning toward Isaac, crouched and tied up behind him. Between the angel and Abraham, the sacrificial lamb ready to replace Isaac on the altar saves his life.

The plant-themed column capitals on the other side are finished off with a story that's not often seen in Galicia, but this blog's readers have seen before, also closely associated with Daniel in the lions' den: the sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham wields a sword, which an angel takes hold of to stop him turning toward Isaac, crouched and tied up behind him. Between the angel and Abraham, the sacrificial lamb ready to replace Isaac on the altar saves his life. On both sides of the door, angels with scrolls create that signature Coruñan shape. Below them, we have additional figures, elongating the indentations. These have both been carved in a Gothic style that harks back to "Mateo" to beautiful effect. The figure on the left is Santiago, bearded and with a pilgrim's walking stick. The younger beardless man on the right is probably Saint John, pointing to the gospel he wrote. A closer look reveals that his head has been replaced, as the angle is slightly uncomfortable and the stone a different color. As it still successfully copies the "Mateo" style, albeit with Gothic waves in his hair, it was probably replaced no later than the fifteenth century.

From the inside, Santiago and John appear to float over the street even as they guard the entrance.

From the inside, Santiago and John appear to float over the street even as they guard the entrance.  Gazing toward the main altar, Santiago reminded me of San Cipriano in my Zamora. Like that temple, it used to have three parallel naves that were turned into a single large nave in Gothic times to create the sense of spaciousness so favored in that artistic period.

Gazing toward the main altar, Santiago reminded me of San Cipriano in my Zamora. Like that temple, it used to have three parallel naves that were turned into a single large nave in Gothic times to create the sense of spaciousness so favored in that artistic period.  The church features many seventeenth-century burials, of which this is the most striking example. This noble lady and her husband are portrayed as praying figures, both with their heads turned drastically to face the altar of their devotion.

The church features many seventeenth-century burials, of which this is the most striking example. This noble lady and her husband are portrayed as praying figures, both with their heads turned drastically to face the altar of their devotion.  This life-sized Saint James survived the medieval fires in the apse and has been moved to the foot of the church, where I stand for perspective. I'd seen a photo of this image before I arrived, and was pleasantly surprised by the presence it exuded because of its size.

This life-sized Saint James survived the medieval fires in the apse and has been moved to the foot of the church, where I stand for perspective. I'd seen a photo of this image before I arrived, and was pleasantly surprised by the presence it exuded because of its size.  The stained glass in the rose windows was placed at the turn of the twentieth century but blends in harmoniously with the medieval architecture.

The stained glass in the rose windows was placed at the turn of the twentieth century but blends in harmoniously with the medieval architecture. In the well-preserved side chapel, a figure of the Virgin Mary, pregnant with the Son of God, is venerated. Such figures are often called Our Lady of the O, because of the surprised reaction they illicit.

In the well-preserved side chapel, a figure of the Virgin Mary, pregnant with the Son of God, is venerated. Such figures are often called Our Lady of the O, because of the surprised reaction they illicit.  Lest we forget the whole point of this building, these column capitals remind us of Santiago and his pilgrimage with the symbolic shell.

Lest we forget the whole point of this building, these column capitals remind us of Santiago and his pilgrimage with the symbolic shell. Santiago is a well-lit place to hang out in the evening.

Santiago is a well-lit place to hang out in the evening.  The blogs Galicia Pueblo a Pueblo and Aquivoltas.com were essential resources for this post.

The blogs Galicia Pueblo a Pueblo and Aquivoltas.com were essential resources for this post.

Published on November 14, 2018 14:42

September 28, 2018

Seven Noble Knights in Search of a Home, Again

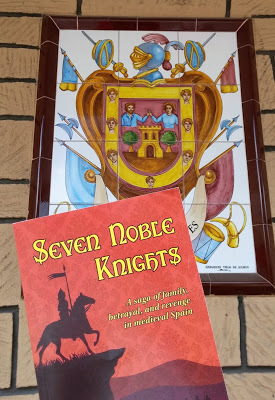

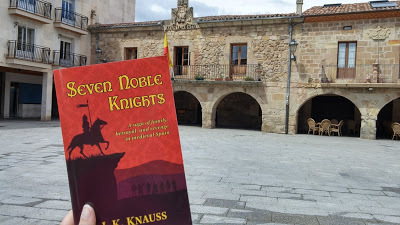

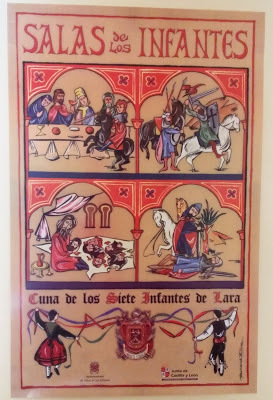

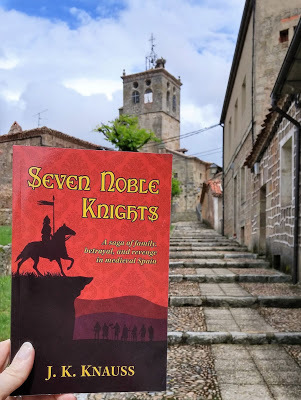

Seven Noble Knights will always belong in Salas de los Infantes... The steps between completing an excellent novel and becoming a published author can be painful and confusing, and frankly, most authors would rather skip them and get to "the good parts." The ones I'm thinking of include researching and querying agents and publishers, receiving multitudes of unhelpful rejections or brushoffs, wading through contracts, and waiting, waiting, waiting.

Seven Noble Knights will always belong in Salas de los Infantes... The steps between completing an excellent novel and becoming a published author can be painful and confusing, and frankly, most authors would rather skip them and get to "the good parts." The ones I'm thinking of include researching and querying agents and publishers, receiving multitudes of unhelpful rejections or brushoffs, wading through contracts, and waiting, waiting, waiting.In the case of my Seven Noble Knights, I experienced all of the above plus an evisceration that ended up vastly helpful to the complete rewrite of the beginning of the novel.

When Seven Noble Knights was accepted for publication, it felt like my writerly dream come true--with all of the trepidation something like that can cause. (I read somewhere that writing long fiction is the most cognitively complex task known to brain researchers. Input from all directions! Is it any wonder that every moment of a writer's life is fraught with mixed feelings? This is not a profession for wimps.)

It turned out to be a long journey from acceptance to publication. I'm thinking about this now because this week, my contract with Bagwyn Books has been terminated and I've received the publishing rights back. Which is to say, Seven Noble Knights is again an unpublished manuscript.

The contract came to an amicable end based on mutually recognized issues at Bagwyn that have nothing to do with my novel. I'm pleased to have the rights back under auspicious circumstances. All the options are open, which is ideal and also scary.

The contract came to an amicable end based on mutually recognized issues at Bagwyn that have nothing to do with my novel. I'm pleased to have the rights back under auspicious circumstances. All the options are open, which is ideal and also scary.It also feels like starting over, but it's really not. Seven Noble Knights has already debuted to critical praise from the Historical Novel Review and thrilled at least two book clubs. I fulfilled my dream of giving a reading and doing a signing at the Harvard Book Store. Seven Noble Knights has rubbed elbows with the Book Doctors, countless luminaries at the Historical Novel Society Conference and the Tin House Summer Workshop, and was the focal point of a lightning-fast radio interview.

My options include researching and approaching more agents and/or publishers, or redoing the launch and publishing myself, or letting it rest for a while until the time is right. I'll definitely consult with a few of my writer friends who have gone through something similar (rights reversion is not uncommon in the volatile publishing industry) before I make a final decision.

So there you have it. Seven Noble Knights will soon be unavailable for purchase. It's an end that promises an even brighter beginning.

Hold onto your bloody cucumbers! Great things are on their way!

Published on September 28, 2018 14:02

September 3, 2018

Burgos's Medieval Mystery: Quintanilla de las Viñas

Santa Maria de Lara and the rocky outcrop I tried to evoke in

Seven Noble Knights

Santa Maria de Lara and the rocky outcrop I tried to evoke in

Seven Noble Knights

All photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss unless otherwise specified In the wild green rolling lands of Lara, southeast of Burgos, a lone traveler may come upon Santa Maria de Lara and feel as if she's discovering it for the first time. This Visigothic temple has been set against a dramatic rocky backdrop that now gives the region its name for more than 1300 years.

Quintanilla de las Viñas seen from Santa Maria de Lara.

Quintanilla de las Viñas seen from Santa Maria de Lara. Most writers discussing the church use the town's name to refer to the temple. I first discovered this rare evidence of Visigothic activity in 2015 during my second adventure in Spain with my beloved, now departed, husband. We were on our way to see Salas de los Infantes and other Seven Noble Knights locations for the first time, so when I saw the diminutive pink sign on the highway that indicated "Visigothic temple, seventh century" this way, we didn't feel we could spare the time that morning.

Santa Maria de Lara with the Castle of Lara de los Infantes behind

Santa Maria de Lara with the Castle of Lara de los Infantes behindPhoto 2015 Jessica Knauss Returning to Burgos after the day's rainy adventures, we drove past a patch of fossilized sauropod tracks and the village of Quintanilla de las Viñas and got the full impact of where the temple sits. The barest indications of civilization, Lara Rock looming with its fascinating caves, and the evocative ruins of the Castle of Lara de los Infantes (where the first Count of Castile was born, I found out later!) off in the distance set the weight of the centuries firmly upon these stones.

It was closed. I mean really closed, as if we were the first people to whom it had occurred to go inside. There was an informative sign with photos of the interior, but no indication that it ever opened. I would have to live through many more experiences over the following three years before this site divulged its secrets to me.

This year, after delving into the fascinating story and fantastic art of San Pedro de la Nave, I was raving to return to Quintanilla de las Viñas to see the inside and slipped it into an epic journey this summer with my adventurous-for-history mother.

This year, after delving into the fascinating story and fantastic art of San Pedro de la Nave, I was raving to return to Quintanilla de las Viñas to see the inside and slipped it into an epic journey this summer with my adventurous-for-history mother.When you come upon the site from town, it's not impressive. The wall that faces you is unadorned and has a bricked-up door. It turns out that even this unsightliness tells us an important part of Quintanilla's story. When it was first built, near the end of Egica's reign, and for a few hundred years thereafter, the church was decorated all around and occupied three times the space it does now. In the ninth or tenth century, a major restoration project was undertaken. Some time after it was donated to the monastery at San Pedro de Arlanza in 1038, Quintanilla entered a long, slow period of decline, and two thirds of the structure caved in and/or was harvested for the stones to be used in other buildings long since vanished.

The space at the front of the building when you approach from the village marks out the temple's original footprint, which was defined during archaeological digs at the site. The wall that greets visitors today was not in the original plans at all. Only a little more than the apse of the original structure now survives. It's when you come around the side that you get a sense that this is more than a hasty pile of rocks.

The space at the front of the building when you approach from the village marks out the temple's original footprint, which was defined during archaeological digs at the site. The wall that greets visitors today was not in the original plans at all. Only a little more than the apse of the original structure now survives. It's when you come around the side that you get a sense that this is more than a hasty pile of rocks. Photo 2015 Stanley Coombs I remember coming around to "the back" in 2015 and being mystified by the multitude of friezes. Now I would recognize these abstruse symbols even out of context as the themes of the most richly decorated exterior of a Visigothic building in all of Spain. Notice also the crosses scratched repeatedly into the less decorated stones. This year, I was able to verify that these are medieval graffiti.

Photo 2015 Stanley Coombs I remember coming around to "the back" in 2015 and being mystified by the multitude of friezes. Now I would recognize these abstruse symbols even out of context as the themes of the most richly decorated exterior of a Visigothic building in all of Spain. Notice also the crosses scratched repeatedly into the less decorated stones. This year, I was able to verify that these are medieval graffiti. Photo 2018 Kay Holt (my lovely mum!) This time, as we approached the open door (visible on the left here), a man popped out of the ranger building (also on the left here). We exchanged greetings and he ended by saying he would be with us momentarily.

Photo 2018 Kay Holt (my lovely mum!) This time, as we approached the open door (visible on the left here), a man popped out of the ranger building (also on the left here). We exchanged greetings and he ended by saying he would be with us momentarily. My mother and I explored for a few minutes by ourselves, and when a Spanish couple arrived, the ranger came back out to give us his grand tour. The elegant vines (Are these the viñas in the town's name?), grape bunches, palm leaves, and birds recall San Pedro de la Nave and have much the same symbolic interpretations attached to them. The birds are the human soul, the palms represent divinity, and the vines and grapes represent the sacramental blood of Christ that gives life to the soul-birds. I've seen similar patterns on modern buildings in Zamora. They may be trying to evoke a time long past, but they mainly imitate these friezes because they're so lovely.

My mother and I explored for a few minutes by ourselves, and when a Spanish couple arrived, the ranger came back out to give us his grand tour. The elegant vines (Are these the viñas in the town's name?), grape bunches, palm leaves, and birds recall San Pedro de la Nave and have much the same symbolic interpretations attached to them. The birds are the human soul, the palms represent divinity, and the vines and grapes represent the sacramental blood of Christ that gives life to the soul-birds. I've seen similar patterns on modern buildings in Zamora. They may be trying to evoke a time long past, but they mainly imitate these friezes because they're so lovely. The pièce de resistance of the exterior is found in the middle frieze, behind the main altar, on the left. Among palm leaves, we find three sets of monograms, which scholars have read as FLNA, DNLA, and FCRN(T). These letters are likely the names of two individuals who gave the money to build or restore the church or the stonemasons themselves, variously interpreted as Flammola and Danila or Flainus and Dilanus, and the Latin fecerunt, "made (this)."

The pièce de resistance of the exterior is found in the middle frieze, behind the main altar, on the left. Among palm leaves, we find three sets of monograms, which scholars have read as FLNA, DNLA, and FCRN(T). These letters are likely the names of two individuals who gave the money to build or restore the church or the stonemasons themselves, variously interpreted as Flammola and Danila or Flainus and Dilanus, and the Latin fecerunt, "made (this)."I love a good building with a mysterious signature!

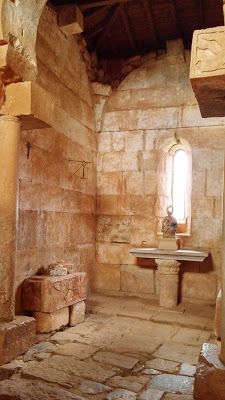

Photo 2018 Kay Holt Walking inside, it's obvious that the building is much smaller now than it was originally because it's hard to contemplate the glorious main archway without backing into the current wall. It's clearly seen better days, and you come to appreciate that the wall was necessary to prevent further deterioration. Even so, what's left takes away the breath of anyone who likes old stuff.

Photo 2018 Kay Holt Walking inside, it's obvious that the building is much smaller now than it was originally because it's hard to contemplate the glorious main archway without backing into the current wall. It's clearly seen better days, and you come to appreciate that the wall was necessary to prevent further deterioration. Even so, what's left takes away the breath of anyone who likes old stuff. Above the arch, barely visible in the photo, rests what is likely the oldest Christ in Majesty in Spain. It, and all the reliefs in the church, have a strong Byzantine vibe that could have been imported to Spain any time between the sixth and tenth centuries, causing some scholars to doubt that the temple is in fact Visigothic.

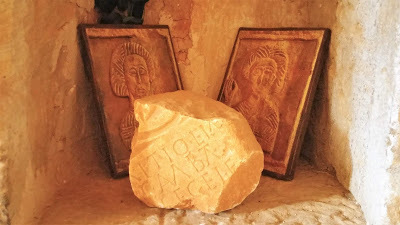

Above the arch, barely visible in the photo, rests what is likely the oldest Christ in Majesty in Spain. It, and all the reliefs in the church, have a strong Byzantine vibe that could have been imported to Spain any time between the sixth and tenth centuries, causing some scholars to doubt that the temple is in fact Visigothic. This snarky blog in Spanish offers a clearer photo of the Christ in Majesty (item 7) and also reveals that in 2004, two panels depicting probable evangelists were stolen from the site. All we saw of the panels this summer were these photos of them in a niche, so I assume their whereabouts are still unknown.

This snarky blog in Spanish offers a clearer photo of the Christ in Majesty (item 7) and also reveals that in 2004, two panels depicting probable evangelists were stolen from the site. All we saw of the panels this summer were these photos of them in a niche, so I assume their whereabouts are still unknown. The magnificent arch continues the signature vines-and-birds theme, but the unique part comes with the brackets under the arch, to the sides, resting on columns probably repurposed from a Roman site. With their symbolism and another signature, they tell tremendous stories about the people who built the temple, if only we knew how to read them.

The magnificent arch continues the signature vines-and-birds theme, but the unique part comes with the brackets under the arch, to the sides, resting on columns probably repurposed from a Roman site. With their symbolism and another signature, they tell tremendous stories about the people who built the temple, if only we knew how to read them.On the left, clearly missing another angel, we have a portrait of a humanoid in a double circle wearing a crescent moon as if it were horns. On either side of its head, the Latin letters LUNA permit no doubt that this is a carryover from pre-Christian worship of celestial bodies. What is it doing in a Christian temple? Some scholars have looked at the frieze on the right bracket and deduced that the Moon here must represent the Virgin Mary or the Church (feminine Ecclesia). Many doubt this because the Moon clearly has a short, thoroughly unfeminine beard, in keeping with the Germanic origin of Moon worship. So its placement here remains a fascinating headscratcher.

The interpretations of the SOL (Sun) frieze on the right as Christ illuminating the world feels more likely. It has a similar problem, though. This Sun looks rather more feminine than we usually think of Jesus. Another shoulder shrug, for sure, even as we admire the strange wings and nimbuses of the angels framing the portrait.

The interpretations of the SOL (Sun) frieze on the right as Christ illuminating the world feels more likely. It has a similar problem, though. This Sun looks rather more feminine than we usually think of Jesus. Another shoulder shrug, for sure, even as we admire the strange wings and nimbuses of the angels framing the portrait.This bracket is doubly wonderful because there was room at the top for a little medieval humility bragging. The letters translate to "Humble Flammola offers this modest gift to God." This gives credence to the "Flammola" reading of the exterior frieze. Many scholars believe this signature is from the ninth or tenth century, which puts me on Seven Noble Knights alert. The name "Flammola" had morphed into "Lambra" by the thirteenth century, when the seven noble knights' legend was first written down. Lambra, the name of the villainess of Seven Noble Knights ! As unusual at it seems today, this name was common in the early Middle Ages, so the Flammola/Lambra who founded or restored this extraordinary church was probably not also the scourge of the heroes in my book. In spite of how close this temple is to Salas and Barbadillo, where the bloody cucumber incident set everything in motion...

Behind all this excitement, we find the area that would've housed the main altar and been the site of the most sacred and secret ceremonies. The wooden roof is completely modern, but it's hard to fathom the age of the stones in the floor.

Behind all this excitement, we find the area that would've housed the main altar and been the site of the most sacred and secret ceremonies. The wooden roof is completely modern, but it's hard to fathom the age of the stones in the floor. This column and capital supporting the rudimentary altar is Roman in origin and was placed here in the twentieth century.

This column and capital supporting the rudimentary altar is Roman in origin and was placed here in the twentieth century. The most interesting pieces in the altar space provoke yet more questions. They're two friezes that may have served as brackets or column capitals in a no-longer-extant archway. They're similar in layout and style to the Sun and Moon friezes, and if possible, their subjects are even more puzzling. This one, on the left, appears to depict a male figure holding a cross. One angel frames the person and the other holds a smaller cross. All the figures have hair that could be mistaken for halos. The informative leaflet I purchased from the ranger at the end of the tour proposes that the central figure here could be the husband of the Flammola who donated the money to build the church. Essentially, that guess is as good as any.

The most interesting pieces in the altar space provoke yet more questions. They're two friezes that may have served as brackets or column capitals in a no-longer-extant archway. They're similar in layout and style to the Sun and Moon friezes, and if possible, their subjects are even more puzzling. This one, on the left, appears to depict a male figure holding a cross. One angel frames the person and the other holds a smaller cross. All the figures have hair that could be mistaken for halos. The informative leaflet I purchased from the ranger at the end of the tour proposes that the central figure here could be the husband of the Flammola who donated the money to build the church. Essentially, that guess is as good as any. Photo 2018 Kay Holt On the right, the same idea is carried out without the crosses. Could this be Flammola? Or are these Christ and the Virgin Mary? More evangelists? In my version of history, someone once wrote down the exact intentions of these bizarre pieces, and a lucky scholar (yours truly?) is destined to find that writing and resolve so many doubts once and for all.

Photo 2018 Kay Holt On the right, the same idea is carried out without the crosses. Could this be Flammola? Or are these Christ and the Virgin Mary? More evangelists? In my version of history, someone once wrote down the exact intentions of these bizarre pieces, and a lucky scholar (yours truly?) is destined to find that writing and resolve so many doubts once and for all.On top of this frieze, the keepers of the site have placed models of the church as it is now and how it's thought to have started out. The contrast confronts the visitor with the ravages of time. When you realize how lucky we are to have even this much of the building to gaze upon, it's also an opportunity to make peace with not having all the answers.

The ranger kindly took our photo with the church and Lara Rock. It was almost laundry day, and my mother and I had ended up with only blue clothes to wear for this monumental visit. It was an honor to be at Quintanilla de las Viñas in such good company, both times.

The ranger kindly took our photo with the church and Lara Rock. It was almost laundry day, and my mother and I had ended up with only blue clothes to wear for this monumental visit. It was an honor to be at Quintanilla de las Viñas in such good company, both times.A visitor in 2012 also had an enjoyable time.

Published on September 03, 2018 00:30

August 28, 2018

Seeking Queen Violante

Lords of all we survey at the top of Allariz

Lords of all we survey at the top of AllarizAll photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss unless otherwise specified. "I didn't even know Alfonso X had a wife," said a Spanish friend of mine the other day.

Of course he had a wife—he was the king and needed legitimate heirs. But while Alfonso X, one of the obsessions of my life, is known to everyone in modern Spain, you don't hear much about his bride, Violante.

While I was studying for my PhD, I heard of a famous scholar of Spanish history who thought of writing Violante's biography. He soon learned why none exists: there just isn't enough information about her to fill a book.

"The Castle," a rocky outcrop at the top of Allariz Violante (a modernized version of this name is Yolanda) was a princess of Aragón, daughter of Jaume the Conqueror and Violante of Hungary. Some sources claim that she married Alfonso when she was only ten years old. Papers were drawn up in 1246, and there may even have been a ceremony, but the marriage was probably not consummated until after she had her first menses.

"The Castle," a rocky outcrop at the top of Allariz Violante (a modernized version of this name is Yolanda) was a princess of Aragón, daughter of Jaume the Conqueror and Violante of Hungary. Some sources claim that she married Alfonso when she was only ten years old. Papers were drawn up in 1246, and there may even have been a ceremony, but the marriage was probably not consummated until after she had her first menses.The lack of information about Violante in a court where it seemed everything was written down, and the existence of two or three bastard-providing lovers of the king, have led some scholars to believe that the marriage was not happy. However, Violante and Alfonso had eleven children together, a number that seems above and beyond strict duty.

[image error] Violante in a thirteenth-century manuscript, Tumbo de Touxos Outos.

Another presumed portrait, from the Libro de ajedrez, is in this blog's banner.

Wikimedia Commons The most lovely evidence that the marriage had tenderness and strength appears in the Cantigas de Santa Maria . Cantiga 345 is full of politics and war, but in the pertinent lines, King Alfonso has a dream that wakes him up. He turns to Queen Violante, who is in the bed next to him, exactly where a beloved spouse should be. Would the Cantigas composers mention this detail if it were false? What reason could they have to make up something like that? What's more, when Alfonso describes his dream to his bedmate, she responds that she's had the same dream. The same dream! That kind of thing is soulmate territory. The king and queen stay together, taking necessary action and celebrating the happy results together, through to the end of the song.

I knew only two other facts about Queen Violante.

One, during the emotionally taxing confusion over who should inherit the kingdom when Alfonso's and Violante's firstborn son was killed in battle in 1275, the queen fled back to Aragón with her two young grandchildren, who stood to gain under Alfonso X's new laws. She eventually returned to court and must've made some kind of peace with her husband and second son, although nothing much more is said about her.

Typical Galician grain storage at the entrance to AllarizSecond, she survived Alfonso X by many years. He died in 1284 and Violante passed away in 1300. The main event recorded about her widowhood was that she founded a convent in the town of Allariz in what is now the province of Ourense in the region of Galicia.

Typical Galician grain storage at the entrance to AllarizSecond, she survived Alfonso X by many years. He died in 1284 and Violante passed away in 1300. The main event recorded about her widowhood was that she founded a convent in the town of Allariz in what is now the province of Ourense in the region of Galicia.I imagined Violante living out her days in the rainy gray weather of Celtic Galicia. For my birthday this year, I wanted to see the place where my fellow widow lived in constant sorrow after the love of her life left her all alone in the world.

Allariz's Praza Maior features the Romanesque

Allariz's Praza Maior features the Romanesque Church of Santiago, which Violante probably visited. I've had help and company for many of my travels over the past year, for which I'm keenly grateful. But this trip had to be solo. All told, I spent more than two hours my first day in the capital of Ourense researching how to get to Allariz and back without my own car and what to see once I got there. I mention this because the character of any travel is influenced not by the destination, but by the journey.

I imagined Violante felt lonely even surrounded by a royal retinue when coming to settle in this green land. Although I was taking taxis, city buses, and intercity buses just as alone, I did it with a sense of accomplishment I could never have achieved from my shotgun position in a friend's car. Those bus rides were, in a way, the culmination of all my years of studying the Spanish language and the history of Spain.

The Galician flag blends in with the Galician sky at the top of Allariz I arrived in Allariz—a big spa town, as it happened—before the convent museum was open, so I headed to what the locals call "The Castle." It was a huge rocky mound with no man-made structures except for a white and blue flag of the region of Galicia that waved stiffly in the strong breezes.

The Galician flag blends in with the Galician sky at the top of Allariz I arrived in Allariz—a big spa town, as it happened—before the convent museum was open, so I headed to what the locals call "The Castle." It was a huge rocky mound with no man-made structures except for a white and blue flag of the region of Galicia that waved stiffly in the strong breezes.I felt like a queen at the top of that rock, looking down at valleys, so many green trees, and roads and houses. Would this have been enough after thirty-two years as the queen of an entire dynamic country? I inhaled the clear air, cool the way August mornings can be with their powerful gusts, and thought that yes, it could be plenty. I recognized the influence of my departed husband in that assessment, and wondered if Violante would ever have agreed.

Convent of Santa Clara, Allariz That's why I made this trip: to learn more about Violante. The convent museum was just opening as I got there. It's enormous... and not very medieval.

Convent of Santa Clara, Allariz That's why I made this trip: to learn more about Violante. The convent museum was just opening as I got there. It's enormous... and not very medieval.Violante founded the convent in 1286 with her son, King Sancho IV, and decided to be buried here, but precisely because it was a royal convent, it had plenty of money to do complete overhauls with changing architectural tastes, and almost nothing of the original convent survives. A fire in the eighteenth century obliterated most of what would've been recognizably Gothic. This convent has the largest cloister in Galicia, but no visits are allowed.

Santa Clara with the Church of San Benito I scoured the convent museum in search of what I'd come looking for. Many reliquaries and liturgical items were of fine artistic quality, but Baroque. Even the Gothic artwork on display was from after Violante's time. Then, in a room all by itself, this:

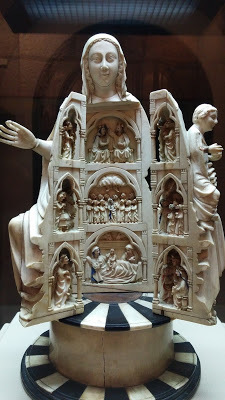

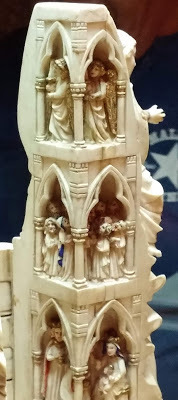

Santa Clara with the Church of San Benito I scoured the convent museum in search of what I'd come looking for. Many reliquaries and liturgical items were of fine artistic quality, but Baroque. Even the Gothic artwork on display was from after Violante's time. Then, in a room all by itself, this: The Virgen Abridera (opening Virgin) was made in the thirteenth century from a single elephant tusk (not okay to do today—don't even think about it), at the behest of Queen Violante. When closed, it looks like a finely carved ivory of a Virgin and Child in the cheerful Gothic style of the thirteenth century.

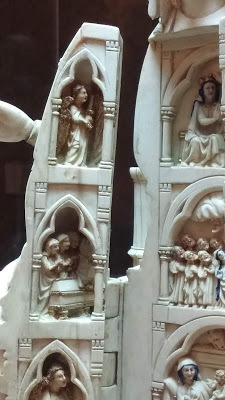

The Virgen Abridera (opening Virgin) was made in the thirteenth century from a single elephant tusk (not okay to do today—don't even think about it), at the behest of Queen Violante. When closed, it looks like a finely carved ivory of a Virgin and Child in the cheerful Gothic style of the thirteenth century. Opened, it becomes a triptych showing Jesus's birth, his Ascension to Heaven, and how Mary was made the Queen of Heaven by her son.

Opened, it becomes a triptych showing Jesus's birth, his Ascension to Heaven, and how Mary was made the Queen of Heaven by her son. The Nativity scene is flanked by an Annunciation in two parts, with Gabriel on the left and the Virgin on the right. On the left of the Ascension, the angel announces Jesus's Resurrection at the tomb, and on the right, Jesus appears as the Holy Spirit to the Apostles. Mary's coronation is flanked by angels holding candles.

The Nativity scene is flanked by an Annunciation in two parts, with Gabriel on the left and the Virgin on the right. On the left of the Ascension, the angel announces Jesus's Resurrection at the tomb, and on the right, Jesus appears as the Holy Spirit to the Apostles. Mary's coronation is flanked by angels holding candles.

The fine details, the remains of medieval paint, and the craftsmanship in the hingework display the highest quality and remind me of my favorite Gothic art, the illustrations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

The fine details, the remains of medieval paint, and the craftsmanship in the hingework display the highest quality and remind me of my favorite Gothic art, the illustrations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. The back of the sculpture shows how Mary's body adjusts to the curve of the tusk out of which she was carved.

The back of the sculpture shows how Mary's body adjusts to the curve of the tusk out of which she was carved. This closeup of the right side shows its 3-D, wedge shape.

This closeup of the right side shows its 3-D, wedge shape.This sculpture had incredible presence. It told all its stories with joy and loving care. Through the ages, anyone who really looked at this ivory has probably been moved in a positive way. In the absence of many facts about Violante's life, I got a visceral feeling for her personality by appreciating one of her possessions.

The opening Virgin also seemed to me an apt metaphor for where I am with widowhood: It rips you open. What you find inside determines the quality of the rest of your life.

Neoclassical fountain in the convent plaza, Allariz Most importantly, in Allariz I learned that the widowed queen did not stay at this convent for the rest of her life, the way I'd assumed. She lived where she was likely happiest, her home in Aragón. She was returning from a pilgrimage to Rome when she died in the Pyrenees mountain pass of Roncesvalles.

Neoclassical fountain in the convent plaza, Allariz Most importantly, in Allariz I learned that the widowed queen did not stay at this convent for the rest of her life, the way I'd assumed. She lived where she was likely happiest, her home in Aragón. She was returning from a pilgrimage to Rome when she died in the Pyrenees mountain pass of Roncesvalles.Good for her. Not shutting herself away, but going where she wanted and living in a way that brought her happiness? That's a widowhood example to follow.

Published on August 28, 2018 03:47

August 20, 2018

A Saint and His Legend in Zamora Today

All photos in this post 2017, 2018 Jessica Knauss I live in a place enchanted by long years of people creating, destroying, and most of all, telling stories.

All photos in this post 2017, 2018 Jessica Knauss I live in a place enchanted by long years of people creating, destroying, and most of all, telling stories.A particularly delightful legend surrounds the first Bishop of Zamora, Saint Atilano. Atilano was a humble man, so humble that he didn't feel worthy of the position of bishop that had been granted him by the king. He decided to perform a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and as he was leaving Zamora, he threw his episcopal ring into the Duero, Zamora's majestic river and the whole reason the city was founded. To finish off the symbolic act, Atilano declared that if he ever came upon the ring again, he would resume the solemn duties of tending to the Zamoran flock of faithful.

In no version of the legend are his travels interesting enough to talk about. This is a story of Zamora, and for that reason, no one knows whether Atilano even made it to the Holy Land or how long he was gone. When he had completed his pilgrimage, or was simply tired of traveling (tenth-century travel was rather more harrowing than our worst tales of airline abuse today), he stopped outside Zamora at an inn to have his midday meal, rest, and clean up from his travels. Digging into the fresh fish on offer that day, what did he find but his very own episcopal ring!

Notice the hefty ring in the fish's mouth. Atilano's humility didn't make him a fool, and he understood a sign when he saw one. He accepted his holy duty to be Bishop of Zamora once again. When he slipped the ring onto his finger, all the bells of Zamora tolled without the influence of bell ringers, and Atilano's ragged travel clothes became the delicately embroidered robes of the highest ecclesiastical office (read: highest office) in the land.

Notice the hefty ring in the fish's mouth. Atilano's humility didn't make him a fool, and he understood a sign when he saw one. He accepted his holy duty to be Bishop of Zamora once again. When he slipped the ring onto his finger, all the bells of Zamora tolled without the influence of bell ringers, and Atilano's ragged travel clothes became the delicately embroidered robes of the highest ecclesiastical office (read: highest office) in the land. This miracle is the main reason the first Bishop of Zamora is considered a saint, and everyone who grew up in Zamora (and avid new residents like yours truly) have a sense of its significance to the city. Zamoran artist Gregorio Fagúndez created this sculpture commemorating the story in 2013, using materials left over from the restoration of the Iron Bridge and calling it "The Legend of the Tenth Century." Calling the miracle story a legend emphasizes the differences in the way Zamorans thought more than a thousand years ago (Did they accept the story at face value?) and our all-too-modern skepticism.

This miracle is the main reason the first Bishop of Zamora is considered a saint, and everyone who grew up in Zamora (and avid new residents like yours truly) have a sense of its significance to the city. Zamoran artist Gregorio Fagúndez created this sculpture commemorating the story in 2013, using materials left over from the restoration of the Iron Bridge and calling it "The Legend of the Tenth Century." Calling the miracle story a legend emphasizes the differences in the way Zamorans thought more than a thousand years ago (Did they accept the story at face value?) and our all-too-modern skepticism.Of course they're right to be skeptical. The story has all the trappings of a folktale, and its legendary character was dramatized for me in a surprising manner this week. I went to the castle for an evening program by El Za-Moro de Zamora, a modern Muslim who loves Zamora's legends, but wanted to give his own take on them. Among jolly audience participation, one of the first themes he came upon was the story of Saint Atilano.

"Who knows the story of Saint Atilano?" he asked a relaxed and knowledgeable audience. I almost raised my hand, but in this case, I'm glad I didn't. If I'd recited my perfect outsider's version of the tale, I would've missed the way the performer had to cajole long-forgotten facts out of several audience members, which made for absurd hilarity and a sense of what it must've been like to grow up with the legend. The first people weren't sure why Atilano didn't want to be bishop, and no one could come up with the idea that he was going to the Holy Land. Things got a little more specific when it came to his return, when he ordered the fish dish at a restaurant over there near that church across the river. The performer used the idea of a restaurant (not exactly the same thing as an inn, but it'll do) to bridge the story with what he wanted to share.

"That's got to be a health code violation," said the performer (I'm translating loosely). "They didn't even clean the fish before they served it!" Then he launched into an even more ancient tale that takes place in "a city in Arabia," which doesn't tell of a bishop, but of a devout jeweler, who is prosperous and appropriately grateful, giving thanks to God with every transaction. One day, however, he lets his guard down and a jealous neighbor sneaks into the shop and steals earrings meant for the princess, throwing them into any nearby body of water. The jeweler was shocked to discover that the earrings were missing and wasn't sure what to do. When his wife was cleaning the fish (unlike the "restaurant" in Zamora) for that evening's meal, what did she find?

"That's got to be a health code violation," said the performer (I'm translating loosely). "They didn't even clean the fish before they served it!" Then he launched into an even more ancient tale that takes place in "a city in Arabia," which doesn't tell of a bishop, but of a devout jeweler, who is prosperous and appropriately grateful, giving thanks to God with every transaction. One day, however, he lets his guard down and a jealous neighbor sneaks into the shop and steals earrings meant for the princess, throwing them into any nearby body of water. The jeweler was shocked to discover that the earrings were missing and wasn't sure what to do. When his wife was cleaning the fish (unlike the "restaurant" in Zamora) for that evening's meal, what did she find?"The bishop's ring!" someone in the audience responded lustily.

"The bishop's ring? How did the bishop's ring get to Arabia? This story takes place long before Atilano threw his ring away! I've never heard anything more surreal," said the performer amiably. But he ended by saying, "Everything's connected."

And in this fish/jewelry story, everything really is. The performer was pointing out that Atilano wouldn't have found his ring in a fish if the jeweler's wife hadn't found earrings in a fish first. The legend is clearly traceable from Zamora to the Middle East (and then farther?) via Andalusia.

The performer said if he had been there, he would've caught the ring and told Atilano not to bother with the travels, because he was clearly going to find the ring again (since his story is based on another, much older one), and he might as well get on with it.