Jessica Knauss's Blog, page 6

June 11, 2019

A Weekend in the Life: A Wedding and a Pilgrimage

San Julián de los Caballeros, Toro, after the wedding

San Julián de los Caballeros, Toro, after the weddingAll photos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss

unless otherwise specified Though I usually blog about the history I find on trips I've taken, sometimes you can have an extraordinary weekend staying close to home. Especially when you live in Spain. To start it off, on Saturday, my choir, the Coral Ciudad de Zamora, sang at a wedding in Toro. I haven't mentioned Toro on this blog before, but that's my bad. It's Zamora province's second capital and about as packed with thrilling history as Zamora. We carpooled to get there, and the lady I rode with, who sings tenor (although she would like to sing bass), parked next to the castle. This is not something you can do at all in the United States, but isn't worth batting an eye in Toro.

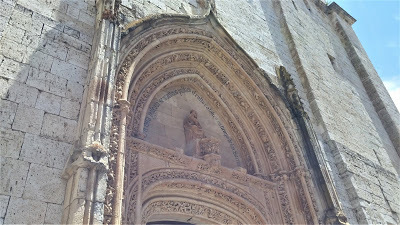

The wedding took place in the Church of San Julián de los Caballeros, a sixteenth-century Gothic structure on the site of a much more ancient sanctuary. Gothic letters on the facade proclaim, "Here the Christian faith was publicly practiced in the time of the 'saracens.'" Alfonso III gave the "repopulation" order for Toro in 910, so this is a reference to worship taking place here in the ninth century and earlier. Such antiquity shouldn't surprise in Toro, which was probably established before 220 BCE.

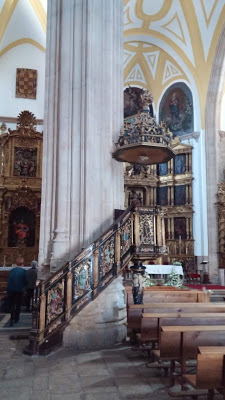

The wedding took place in the Church of San Julián de los Caballeros, a sixteenth-century Gothic structure on the site of a much more ancient sanctuary. Gothic letters on the facade proclaim, "Here the Christian faith was publicly practiced in the time of the 'saracens.'" Alfonso III gave the "repopulation" order for Toro in 910, so this is a reference to worship taking place here in the ninth century and earlier. Such antiquity shouldn't surprise in Toro, which was probably established before 220 BCE. Gothic pulpit We had the chance to look around in the church, change into choir robes in the sacristy, and warm up before any guests arrived.

Gothic pulpit We had the chance to look around in the church, change into choir robes in the sacristy, and warm up before any guests arrived.Hardly anybody came into the church before the ceremony started. A fellow soprano said they were waiting around outside to catch a glimpse of the bride. No way! Rather than follow the rules, the Spanish don't mind spoiling the surprise.

An alto's husband took this photo of us during warmups. The groom was handsome, the bride elegant. The choir didn’t make any obvious flubs, and word from the family is that our contribution was thoroughly appreciated. Although there didn't seem to be a videographer, as I've seen at most American weddings, two photographers pestered the bride and groom and ignored us completely. Choirs at weddings in Spain must be so normal as to not need a photographic reminder.

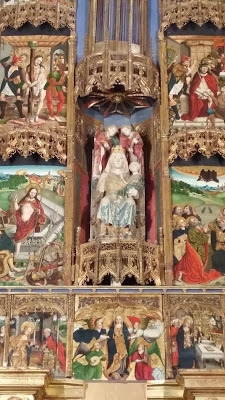

An alto's husband took this photo of us during warmups. The groom was handsome, the bride elegant. The choir didn’t make any obvious flubs, and word from the family is that our contribution was thoroughly appreciated. Although there didn't seem to be a videographer, as I've seen at most American weddings, two photographers pestered the bride and groom and ignored us completely. Choirs at weddings in Spain must be so normal as to not need a photographic reminder. Main altar There was mass while the bride and groom were seated. They exchanged vows, rings, and arras, coins symbolic of dowry and bride price, though they said they were symbolic of the fortunes the bride and groom would enjoy together.

Main altar There was mass while the bride and groom were seated. They exchanged vows, rings, and arras, coins symbolic of dowry and bride price, though they said they were symbolic of the fortunes the bride and groom would enjoy together.The groom's brother carried a cardboard sign nicely lettered with "Don't worry, ladies, I'm still single!" Well, that's a relief!

The groom’s new aunt read a text of blessing as a surprise, and a nervous friend sang a short song, sitting in the pews. It wasn't the performance of the year, as the choir commented afterward, but I was moved by her sentiment.

A meet-and-greet instead of a recessional Though we sang an upbeat song by Monsignor Marco Frisina as a recessional, the wedding party didn't leave the church at the end. All the invited friends and family went up to them near the altar to congratulate them. Outside, there were three baskets with different things to throw at the couple when they did come out: rice, rose petals, and confetti canons.

A meet-and-greet instead of a recessional Though we sang an upbeat song by Monsignor Marco Frisina as a recessional, the wedding party didn't leave the church at the end. All the invited friends and family went up to them near the altar to congratulate them. Outside, there were three baskets with different things to throw at the couple when they did come out: rice, rose petals, and confetti canons.

This is the first wedding I've been to since I became widowed. I almost broke down in tears during the exchange of rings, thinking widow thoughts that would be a real downer to anyone who's been spared losing the love of their life. And then, looking at the happy couple being pelted with the modern remnants of fertility symbols, I couldn't help but feel optimistic. The day was emotionally exhausting because of these ups and downs. Grief always comes back around with the same intensity, but at least I find that now, nearly three years in, I recover from such triggers quickly, with a little rest.

This is the first wedding I've been to since I became widowed. I almost broke down in tears during the exchange of rings, thinking widow thoughts that would be a real downer to anyone who's been spared losing the love of their life. And then, looking at the happy couple being pelted with the modern remnants of fertility symbols, I couldn't help but feel optimistic. The day was emotionally exhausting because of these ups and downs. Grief always comes back around with the same intensity, but at least I find that now, nearly three years in, I recover from such triggers quickly, with a little rest.

Singing at a wedding on Saturday would've been enough to distinguish this weekend from any other in my life, but Zamora can be relentless. It provided another unique event to transport me to yet another world.

Singing at a wedding on Saturday would've been enough to distinguish this weekend from any other in my life, but Zamora can be relentless. It provided another unique event to transport me to yet another world. The highway is blocked to car traffic on the morning of Pentecost Monday every year. June in Spain is synonymous with weddings, but also with romerías. The translation is "pilgrimages," but yet again, something is lost in that transfer. A romería, unlike what we usually think of as a pilgrimage, is a local affair, something that can be undertaken in a single day by an entire community. It turns out looking like a mass migration to the countryside for the day. The most famous is the romería from Sevilla to El Rocío, but I've seen national news reports on many others all over the country.

The highway is blocked to car traffic on the morning of Pentecost Monday every year. June in Spain is synonymous with weddings, but also with romerías. The translation is "pilgrimages," but yet again, something is lost in that transfer. A romería, unlike what we usually think of as a pilgrimage, is a local affair, something that can be undertaken in a single day by an entire community. It turns out looking like a mass migration to the countryside for the day. The most famous is the romería from Sevilla to El Rocío, but I've seen national news reports on many others all over the country.  Guess what? Zamora's romería claims to be the oldest continually performed such ritual. The media claims this is the 729th year! In about the year 1290, it's said young King Sancho IV (Alfonso X's son) was out hunting in the area of present-day La Hiniesta when the Virgin Mary appeared to him in a broom shrub (hiniesta). He had the church that is now the center of town built to commemorate that auspicious moment. And people have been making the pilgrimage out here from Zamora on Pentecost ever since.

Guess what? Zamora's romería claims to be the oldest continually performed such ritual. The media claims this is the 729th year! In about the year 1290, it's said young King Sancho IV (Alfonso X's son) was out hunting in the area of present-day La Hiniesta when the Virgin Mary appeared to him in a broom shrub (hiniesta). He had the church that is now the center of town built to commemorate that auspicious moment. And people have been making the pilgrimage out here from Zamora on Pentecost ever since.  Someone who goes on romería is a romero,

Someone who goes on romería is a romero,so sprigs of romero (rosemary) are required. Last year, the romería came up without enough warning for me to consider doing it. Besides, walking seven kilometers there and seven more back by myself in a crowd didn't appeal when I was finishing up my first school year and preparing for an epic journey with my wonderful mother.

This year June 10, a Monday, was a holiday in Zamora and nowhere else. Chatting with my roommate, Fernando, the romería to La Hiniesta came up casually with enough time beforehand for him to consider that since I love Zamora and haven't done it before, perhaps he could do me the extraordinary favor of guiding me through the experience.

The Cross of Don Sancho, one of the important stops along the way I needed a local guide because these things are hard to pin down, even if they've published schedules and itineraries. I wouldn't have known what time to be at the church from which the Patroness of Zamora, the Virgen de la Concha (Our Lady of the Shell), makes her grand exit. I also wouldn't have had the motivation to get up so early.

The Cross of Don Sancho, one of the important stops along the way I needed a local guide because these things are hard to pin down, even if they've published schedules and itineraries. I wouldn't have known what time to be at the church from which the Patroness of Zamora, the Virgen de la Concha (Our Lady of the Shell), makes her grand exit. I also wouldn't have had the motivation to get up so early.We showed up at San Antolín at 8:30 a.m. Only bakers and romeros (pilgrimage-goers) are up at that hour in Spain. Everyone else I'd talked to about it had said they were going to be away from Zamora on Monday, so I had the impression of a deserted city. That impression was the first thing corrected.

The Virgen de la Concha came out of San Antolín punctually to a march played by flute and tambor, a harsh type of oboe, and bagpipes. These musical groups spread out over the course of the route, but were most impressive when they were all together. The Virgen has been the Patroness of Zamora since 1100, but the current iconographically unique dressing image is from the eighteenth century. She stands proudly with a flag, and her Child stands next to her, united by a silver chain. The shell that gives her her name is also silver and tied around her waist over whatever elaborate robes she's dressed with. Because she's a dressing image, under the robes, she's a skeletal framework, making her relatively light, which must be a blessing on her romería day. Seven kilometers (4.35 miles) to La Hiniesta, a trip around the large church there, and seven kilometers back on the same day would test anyone's devotion.

The Virgen de la Concha came out of San Antolín punctually to a march played by flute and tambor, a harsh type of oboe, and bagpipes. These musical groups spread out over the course of the route, but were most impressive when they were all together. The Virgen has been the Patroness of Zamora since 1100, but the current iconographically unique dressing image is from the eighteenth century. She stands proudly with a flag, and her Child stands next to her, united by a silver chain. The shell that gives her her name is also silver and tied around her waist over whatever elaborate robes she's dressed with. Because she's a dressing image, under the robes, she's a skeletal framework, making her relatively light, which must be a blessing on her romería day. Seven kilometers (4.35 miles) to La Hiniesta, a trip around the large church there, and seven kilometers back on the same day would test anyone's devotion.

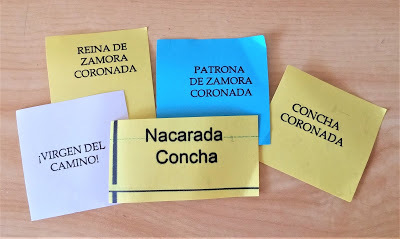

As she made her way down the sloped street to exit what was once the Fair Gate in the city wall, people in balconies threw confetti. This wasn't just any confetti. It had been cut with care from multicolored paper after being printed with all the Virgen's honorifics: Crowned Queen of Zamora, Crowned Patron of Zamora, Virgin of the Pilgrim's Way!, Mother-of-Pearl Shell, and Crowned Shell were the ones Fernando caught for me.

As she made her way down the sloped street to exit what was once the Fair Gate in the city wall, people in balconies threw confetti. This wasn't just any confetti. It had been cut with care from multicolored paper after being printed with all the Virgen's honorifics: Crowned Queen of Zamora, Crowned Patron of Zamora, Virgin of the Pilgrim's Way!, Mother-of-Pearl Shell, and Crowned Shell were the ones Fernando caught for me. The idea is not to simply leave the temple and arrive at La Hiniesta in a timely manner. Several diversions, planned and improvised, kept boredom at bay throughout the trip. Among the spontaneous events, some people waited by the side of the road for the procession to pass by, holding flowers. If they held the flowers up while the Virgen approached, the float stopped and allowed the people to make votive offerings of the flowers. One of the brotherhood members would take the flowers and arrange them on the float as he saw fit.

The idea is not to simply leave the temple and arrive at La Hiniesta in a timely manner. Several diversions, planned and improvised, kept boredom at bay throughout the trip. Among the spontaneous events, some people waited by the side of the road for the procession to pass by, holding flowers. If they held the flowers up while the Virgen approached, the float stopped and allowed the people to make votive offerings of the flowers. One of the brotherhood members would take the flowers and arrange them on the float as he saw fit. The first programmed stop was just outside the Fair Gate. The Virgen entered the Church of San Lázaro, prayers were said and reverences made, and she made a triumphal exit accompanied by music.

The first programmed stop was just outside the Fair Gate. The Virgen entered the Church of San Lázaro, prayers were said and reverences made, and she made a triumphal exit accompanied by music.Fernando said when he used to do the romería as a kid, only "four cats" would show up. That's the Spanish way of exaggerating to say "nobody." Monday, the street near San Antolín was crammed with people, more people watched from their balconies, and more and more people joined the parade as it wended out of Zamora. It was truly a community affair. I saw people from my choir, a former student played in one of the bands, and Fernando was constantly running into people he knew.

By 9:30, we'd already arrived at the Cross of Don Sancho, a little wooded area where the procession stopped and prayers were said.

By 9:30, we'd already arrived at the Cross of Don Sancho, a little wooded area where the procession stopped and prayers were said.  Then a couple of the brotherhood members ceremoniously unchained Christ from his mother and cradled him reverently for the faithful to come and kiss his feet. Given that I'm not Catholic and Fernando is lapsed (apostate, he says), we only watched. At this point, though we didn't realize it, Christ was taken ahead by car.

Then a couple of the brotherhood members ceremoniously unchained Christ from his mother and cradled him reverently for the faithful to come and kiss his feet. Given that I'm not Catholic and Fernando is lapsed (apostate, he says), we only watched. At this point, though we didn't realize it, Christ was taken ahead by car. We passed the sign that indicated we were leaving Zamora and broke out into open country. I admit to getting a thrill for doing that on foot. I've only ever seen those signs from cars before. Sadly, the landscape looks almost as dry as it did when I first arrived in 2017. Last year, it must've looked much greener after a lot of refreshing spring rain we didn't get this year.

We passed the sign that indicated we were leaving Zamora and broke out into open country. I admit to getting a thrill for doing that on foot. I've only ever seen those signs from cars before. Sadly, the landscape looks almost as dry as it did when I first arrived in 2017. Last year, it must've looked much greener after a lot of refreshing spring rain we didn't get this year. We were able to keep up a brisk pace, and the day was clear but not hot. The highway was closed to automobile traffic, which made for a lot of peace of mind. Red poppies lined the highway.

We were able to keep up a brisk pace, and the day was clear but not hot. The highway was closed to automobile traffic, which made for a lot of peace of mind. Red poppies lined the highway. The fork leading to the route back if you stay with the procession all day We came up on the refreshments stop less than fifteen minutes after leaving the Cross of Don Sancho. The free "lemonade" was an insipid red liquid I chose not to do more than taste because restrooms were clearly going to be scarce. Fernando had brought roasted peanuts, and we walked and shelled them, shooting the breeze under the protection of hats.

The fork leading to the route back if you stay with the procession all day We came up on the refreshments stop less than fifteen minutes after leaving the Cross of Don Sancho. The free "lemonade" was an insipid red liquid I chose not to do more than taste because restrooms were clearly going to be scarce. Fernando had brought roasted peanuts, and we walked and shelled them, shooting the breeze under the protection of hats. We entered industrial farmland, and considerate farmers had laid down carpets of rose petals and rosemary to attenuate the "fresh" smell of animals.

We entered industrial farmland, and considerate farmers had laid down carpets of rose petals and rosemary to attenuate the "fresh" smell of animals. At 10:30, we came across an informal stop. "What are they giving out there?" asked Fernando. We looked closer, and it was the car with Christ. They'd stopped to allow for more foot kissing and claimed that donations were welcome. For the brotherhood, of course. I thought it was highly amusing.

At 10:30, we came across an informal stop. "What are they giving out there?" asked Fernando. We looked closer, and it was the car with Christ. They'd stopped to allow for more foot kissing and claimed that donations were welcome. For the brotherhood, of course. I thought it was highly amusing. Only a little farther on, large groups of people were sitting by the side of the road, eating sandwiches and other second-breakfast items they'd brought. They likely knew exactly how little room there was to do this kind of thing in La Hiniesta.

Only a little farther on, large groups of people were sitting by the side of the road, eating sandwiches and other second-breakfast items they'd brought. They likely knew exactly how little room there was to do this kind of thing in La Hiniesta.

When we arrived ahead of the procession at the entrance to the village at about 11, we found a place set up with barriers where the action would clearly take place. I said I needed to get a look at the church before it was overrun with pilgrims. We hotfooted it to the center of town and made it just in time to see the Brotherhood of La Hiniesta leaving to meet the Virgen de la Concha at her arrival.

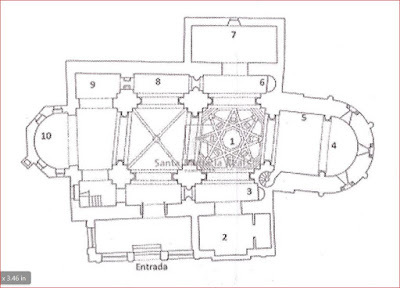

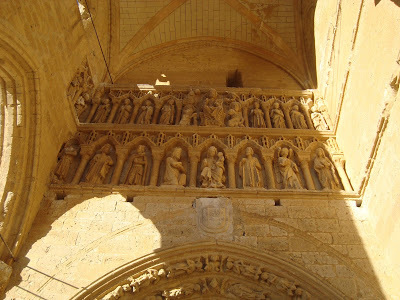

When we arrived ahead of the procession at the entrance to the village at about 11, we found a place set up with barriers where the action would clearly take place. I said I needed to get a look at the church before it was overrun with pilgrims. We hotfooted it to the center of town and made it just in time to see the Brotherhood of La Hiniesta leaving to meet the Virgen de la Concha at her arrival. The church, one of the few pieces of Gothic architecture in Zamora province, is spectacular. The grand doorway has the ball decorations no one can tell by sight alone whether they are Romanesque or Isabelline Gothic. In this case, history shows us they are Isabelline. The interior is a single nave with impressive Baroque pieces and three fine Gothic statues. We read that there were Gothic paintings, but didn't find them. They may have been behind the main altar.

The church, one of the few pieces of Gothic architecture in Zamora province, is spectacular. The grand doorway has the ball decorations no one can tell by sight alone whether they are Romanesque or Isabelline Gothic. In this case, history shows us they are Isabelline. The interior is a single nave with impressive Baroque pieces and three fine Gothic statues. We read that there were Gothic paintings, but didn't find them. They may have been behind the main altar. The main event is the facade. It's packed with masterful Gothic sculpture you simply don't expect in Zamora, highlighted by colorful paint.

The main event is the facade. It's packed with masterful Gothic sculpture you simply don't expect in Zamora, highlighted by colorful paint. Being Gothic, the scenes are all strictly religious, illustrating the life of Christ. But I could've stared at the sinuous, expressive forms for much longer than the three minutes we spared before running back to meet the procession. Looking at the photos, I dare say this Gothic style is influenced by the Romanesque symmetry all around the province.

Being Gothic, the scenes are all strictly religious, illustrating the life of Christ. But I could've stared at the sinuous, expressive forms for much longer than the three minutes we spared before running back to meet the procession. Looking at the photos, I dare say this Gothic style is influenced by the Romanesque symmetry all around the province. Horses weren't allowed to participate in the ceremonies this year,

Horses weren't allowed to participate in the ceremonies this year, but they came to watch.

Back at the entrance, we got a pretty good spot to watch the arrival of the Virgen. The brotherhood members intoned a song. A couple of children doing their first communion read poems including the phrase "I will never forget this day." The mayors of Zamora and La Hiniesta traded the canes that are the symbol of their responsibilities. They trade them back after the mass, before the procession heads back to Zamora.

Back at the entrance, we got a pretty good spot to watch the arrival of the Virgen. The brotherhood members intoned a song. A couple of children doing their first communion read poems including the phrase "I will never forget this day." The mayors of Zamora and La Hiniesta traded the canes that are the symbol of their responsibilities. They trade them back after the mass, before the procession heads back to Zamora.What everyone wanted to see was this, the dance of the brotherhoods' flags.

Then we processed again, to the church!

Ringing the bells

Ringing the bells

The Virgen made a circuit of the whole church, accompanied by the bands and the bellringers, before making a triumphal entry. Not nearly all the pilgrims would fit into the church for the solemn mass, and it seemed as though most didn't try.

The Virgen made a circuit of the whole church, accompanied by the bands and the bellringers, before making a triumphal entry. Not nearly all the pilgrims would fit into the church for the solemn mass, and it seemed as though most didn't try. Fernando said in the old days, plenty of the town's bars were open to provide restrooms and refreshments to the pilgrims. This time, only an outdoor events place was open--right on the side of the church. They were doing excellent business. Something must've happened over the years to make the local bars give up, because absolutely nothing was open. If not for the thousands of pilgrims, La Hiniesta would've been a ghost town.

Fernando said in the old days, plenty of the town's bars were open to provide restrooms and refreshments to the pilgrims. This time, only an outdoor events place was open--right on the side of the church. They were doing excellent business. Something must've happened over the years to make the local bars give up, because absolutely nothing was open. If not for the thousands of pilgrims, La Hiniesta would've been a ghost town.One of my devious roommate's ideas for not having to walk back to Zamora was to limp, moaning, into the Red Cross tent, and keep up the act until they take you home in an ambulance. There was no way I was doing that, but the Red Cross had port-a-potties, for which I will be eternally grateful. At about 1 p.m., after an incredible morning, and having our photo taken by someone else Fernando knew, we were confronted with this:

Four kilometers back to Zamora, plus the kilometers from the city limit to our house. On foot. Although the day was fine for walking, the return was tiresome because the highway was now open to traffic and, importantly, it was getting close to time for the midday meal.

Four kilometers back to Zamora, plus the kilometers from the city limit to our house. On foot. Although the day was fine for walking, the return was tiresome because the highway was now open to traffic and, importantly, it was getting close to time for the midday meal.We started toward Zamora, and Fernando tried what had always worked before: hitchhiking. "Nobody really hitchhikes anymore, do they?" he said after seven or eight attempts, echoing something I'd said earlier. Then we saw someone carrying an oboe wave down what was obviously a prearranged ride.

"He has a ride," I said, and we ran up the road a way. After they'd turned around, Fernando's trusty thumb finally worked.

Riding with one of the musicians afforded us a conversation about how much the romería has changed and a comment about the way the mayors exchange canes. "Just think, the Mayor of La Hiniesta could make a decree during those few hours and Zamorans would have to live by it!"

And we made it home in time for the midday meal after a nice shower. It was hard to believe the rest of the world, and even the rest of Spain, had been going about normal business on this extraordinary day, the day of the romería to La Hiniesta.

Published on June 11, 2019 15:30

May 31, 2019

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Santiago de los Caballeros

Santiago de los Caballeros in the middle of the Field of Truth,

Santiago de los Caballeros in the middle of the Field of Truth, seen from the castle

Photos in this post 2017, 2018, 2019 Jessica Knauss When you visit Zamora, you're likely to see Santiago de los Caballeros for the first time as you gaze down at the Field of Truth from the eleventh-century city walls or the ruins of the castle. I sometimes take a little walk to get this this view and marvel that I live here. In this post, I'm sharing the oldest Romanesque structure in the city in order to celebrate my assignment to the same school in Zamora for next school year. (Three in a row! That's the longest I've stayed anywhere in decades!)

It's known as St. James of the Knights because throughout the Middle Ages, this was where squires came to do a nightlong vigil and be knighted in a ceremony the following day. The current structure has elements from the beginning of the twelfth century. The rudimentary north and western facades (seen above) are likely hasty reconstructions from the late twelfth century and later. Like other Romanesque churches here, it's made from lovely golden and rose-colored local stones. From afar, it looks small, an impression that doesn't change as you come closer.

It's known as St. James of the Knights because throughout the Middle Ages, this was where squires came to do a nightlong vigil and be knighted in a ceremony the following day. The current structure has elements from the beginning of the twelfth century. The rudimentary north and western facades (seen above) are likely hasty reconstructions from the late twelfth century and later. Like other Romanesque churches here, it's made from lovely golden and rose-colored local stones. From afar, it looks small, an impression that doesn't change as you come closer. Santiago's "good side" has the intact early twelfth-century apse. The most famous knight to undergo the vigil and ceremony on this site was Ruy Díaz de Vivar, later known as El Cid (c. 1043 - 1099). A visit to Santiago de los Caballeros is a stroll through history and legend. To keep it short, it's said that after he discovered his king, Sancho I, had been assassinated, El Cid chased the murderer, Bellido Dolfos, from the Door of Loyalty (previously the Door of Betrayal) in the city wall near the castle into the field where Santiago de los Caballeros sits. There, El Cid apprehended Bellido Dolfos, and the open area has been called the Field of Truth ever since.

Santiago's "good side" has the intact early twelfth-century apse. The most famous knight to undergo the vigil and ceremony on this site was Ruy Díaz de Vivar, later known as El Cid (c. 1043 - 1099). A visit to Santiago de los Caballeros is a stroll through history and legend. To keep it short, it's said that after he discovered his king, Sancho I, had been assassinated, El Cid chased the murderer, Bellido Dolfos, from the Door of Loyalty (previously the Door of Betrayal) in the city wall near the castle into the field where Santiago de los Caballeros sits. There, El Cid apprehended Bellido Dolfos, and the open area has been called the Field of Truth ever since. When I pointed out Santiago de los Caballeros and its connections to the famous hero, my friend said, "I didn't know El Cid was in Zamora." Come on, the first half of the El Cid film takes place in Zamora! Zamora, an open secret of spectacular history.

When I pointed out Santiago de los Caballeros and its connections to the famous hero, my friend said, "I didn't know El Cid was in Zamora." Come on, the first half of the El Cid film takes place in Zamora! Zamora, an open secret of spectacular history. Santiago de los Caballeros below the castle and cathedral bell tower

Santiago de los Caballeros below the castle and cathedral bell tower

In spite of its illustrious past, Santiago de los Caballeros gives off an air of humility today. Its placement near the river has exposed it to repeated flooding and continual repair. It seems each time it was repaired, the more basic the construction. The only decoration left to the twelfth-century entrance is that Romanesque predilection, a checkerboard pattern.

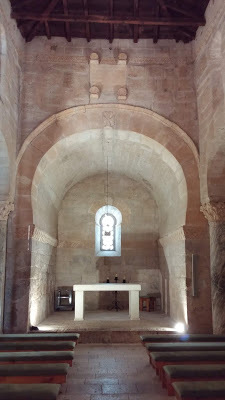

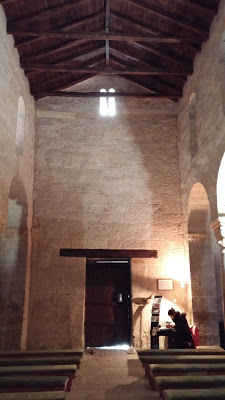

In spite of its illustrious past, Santiago de los Caballeros gives off an air of humility today. Its placement near the river has exposed it to repeated flooding and continual repair. It seems each time it was repaired, the more basic the construction. The only decoration left to the twelfth-century entrance is that Romanesque predilection, a checkerboard pattern. That's the caretaker. Stepping inside, the small space creates intimacy. When the door is left open, it's more than enough to flood the space with light. It has two levels of floor, surely the result of building works at different points of sedimentary history. Both levels have medieval tombs under them.

That's the caretaker. Stepping inside, the small space creates intimacy. When the door is left open, it's more than enough to flood the space with light. It has two levels of floor, surely the result of building works at different points of sedimentary history. Both levels have medieval tombs under them.Looking toward the foot, picture the plaster-covered walls replete with colorful paintings and you'll have a better idea of what Santiago was like when it was first built and used.

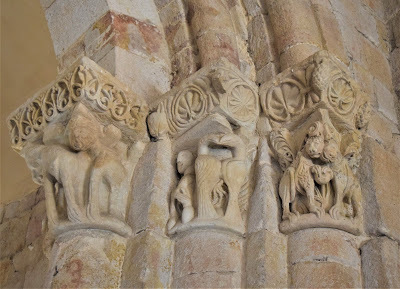

The lack of features in the rest of the building puts the focus on the parts that come to us directly from the early twelfth century: columns that might once have supported an arch, complete with capitals that are unique in Zamora; a triumphal arch some critics have said looks more like a doorway; and the tiny semicircular apse.

The lack of features in the rest of the building puts the focus on the parts that come to us directly from the early twelfth century: columns that might once have supported an arch, complete with capitals that are unique in Zamora; a triumphal arch some critics have said looks more like a doorway; and the tiny semicircular apse. As usual, the meaty art is in the column capitals. The two large capitals before the apse both have simas with leaves, vines, and compressed palms not unlike the ones in San Claudio de Olivares. Many critics believe this is Asturian influence. To my eyes, it looks like a natural continuation of the sima tradition seen first in San Pedro de la Nave.

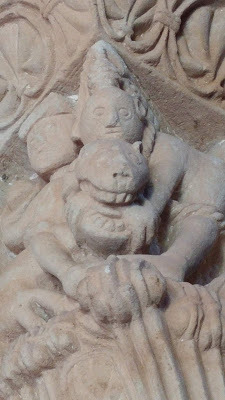

As usual, the meaty art is in the column capitals. The two large capitals before the apse both have simas with leaves, vines, and compressed palms not unlike the ones in San Claudio de Olivares. Many critics believe this is Asturian influence. To my eyes, it looks like a natural continuation of the sima tradition seen first in San Pedro de la Nave.This first capital is worth viewing from every angle, such is the inscrutable confusion of forms.

Every interpretation I've read claims that this is a sculptural representation of Hell, complete with all manner of fornication. Is it Hell, or the earthly behavior that leads to that low place? Before reading about this capital, I thought it was acrobats, a popular subject in Romanesque sculpture with multiple interpretations. Given the chaotic nature of the composition, it's likely the most negative connotations are the correct ones. Acrobats could indeed represent sins of the flesh, but looking closer, the sins appear to be represented literally.

Every interpretation I've read claims that this is a sculptural representation of Hell, complete with all manner of fornication. Is it Hell, or the earthly behavior that leads to that low place? Before reading about this capital, I thought it was acrobats, a popular subject in Romanesque sculpture with multiple interpretations. Given the chaotic nature of the composition, it's likely the most negative connotations are the correct ones. Acrobats could indeed represent sins of the flesh, but looking closer, the sins appear to be represented literally. The inclusion of a horse on the side and heads of oxen in the sima further emphasize the theme of humans committing the sin of surrendering to their animal nature. I adore the numerous faces, the honest execution, and the inventiveness of the forms. Call me lurid, but this may be my favorite capital in Zamora.

The inclusion of a horse on the side and heads of oxen in the sima further emphasize the theme of humans committing the sin of surrendering to their animal nature. I adore the numerous faces, the honest execution, and the inventiveness of the forms. Call me lurid, but this may be my favorite capital in Zamora. Some Romanesque churches like to balance out the themes in their capitals by portraying opposite concepts across the aisle. Not so here. Clearly done by the same delightful artist, this capital shows the consequences of the actions in the first. The flames of Hell rise out of an Asturian-inspired rope decoration. Ropes are a continued theme as the tortured souls appear to be tied to the exotic beasts that punish them, with obvious allegorical value.

Some Romanesque churches like to balance out the themes in their capitals by portraying opposite concepts across the aisle. Not so here. Clearly done by the same delightful artist, this capital shows the consequences of the actions in the first. The flames of Hell rise out of an Asturian-inspired rope decoration. Ropes are a continued theme as the tortured souls appear to be tied to the exotic beasts that punish them, with obvious allegorical value. This poor fellow appears to be giving his tormentor a hug while it gnaws his hands off. This particular scene could have a subconnotation of the way time consumes all living things. But time is hardly a factor when you're enduring the eternal torments of the damned.

This poor fellow appears to be giving his tormentor a hug while it gnaws his hands off. This particular scene could have a subconnotation of the way time consumes all living things. But time is hardly a factor when you're enduring the eternal torments of the damned.  Turning our attention to the apse, the semicircular arch over the quadrilateral structure of the columns makes a perfect metaphor for the union between heaven and earth. The semicircular apse has three small windows and a stone checkerboard border. A simple table altar stands over the Renaissance tomb of one of Zamora's bishops. It would be hard to cram more sacredness into this limited space. During one of my visits here, I found this view to be as useful to a meditative state as a view of nature.

Turning our attention to the apse, the semicircular arch over the quadrilateral structure of the columns makes a perfect metaphor for the union between heaven and earth. The semicircular apse has three small windows and a stone checkerboard border. A simple table altar stands over the Renaissance tomb of one of Zamora's bishops. It would be hard to cram more sacredness into this limited space. During one of my visits here, I found this view to be as useful to a meditative state as a view of nature. The triumphal arch has three fractional columns on each side, and their capitals line up in a row. On the left, delicately carved plant decorations that echo the simas, Adam and Eve after the original sin with the Serpent winding around them like a boa constrictor, and the expulsion from Eden.

The triumphal arch has three fractional columns on each side, and their capitals line up in a row. On the left, delicately carved plant decorations that echo the simas, Adam and Eve after the original sin with the Serpent winding around them like a boa constrictor, and the expulsion from Eden. The Adam and Eve figures are strange and rudimentary, but the serpent symbolism is original. In this view, we see the other side of the expulsion capital, which has facing lions. Remember them.

The Adam and Eve figures are strange and rudimentary, but the serpent symbolism is original. In this view, we see the other side of the expulsion capital, which has facing lions. Remember them. What's left of Adam and Eve in the expulsion from Eden is again crudely executed, in the same style as the serpent capital. Rather than merely covering themselves with found objects, however, we can see Eve is wearing a tunic that, while basic, doesn't have to be held together with the hands. She still modestly crosses her arms in front.

What's left of Adam and Eve in the expulsion from Eden is again crudely executed, in the same style as the serpent capital. Rather than merely covering themselves with found objects, however, we can see Eve is wearing a tunic that, while basic, doesn't have to be held together with the hands. She still modestly crosses her arms in front. On the opposite side, the same artist placed indistinct four-legged beasts, facing birds and a man, and facing lions in a jungle-like scene. The enigmatic man appears to be protected by the birds, barely visible behind them. Birds can be representations of the human soul, or they can protect the human soul, which is sometimes symbolized with an anonymous human being. I like this interpretation because the man's pleasant expression indicates he has no worries: these birds are protecting him.

On the opposite side, the same artist placed indistinct four-legged beasts, facing birds and a man, and facing lions in a jungle-like scene. The enigmatic man appears to be protected by the birds, barely visible behind them. Birds can be representations of the human soul, or they can protect the human soul, which is sometimes symbolized with an anonymous human being. I like this interpretation because the man's pleasant expression indicates he has no worries: these birds are protecting him. The lions in this group are the best sculptures in the church. The lions on the other side appear to be rough drafts, and these the final development. Here we can see why the lion came to be called "king of the jungle." But the leaves and branches here aren't meant to represent just any plant. These lions are guarding the Tree of Life. Nobody's getting past those fearsome claws!

The lions in this group are the best sculptures in the church. The lions on the other side appear to be rough drafts, and these the final development. Here we can see why the lion came to be called "king of the jungle." But the leaves and branches here aren't meant to represent just any plant. These lions are guarding the Tree of Life. Nobody's getting past those fearsome claws! Santiago de los Caballeros is in use today. It's served by the same priest who gives mass in neighboring San Claudio de Olivares. It has endured the ravages of weather for about 900 years. For two years, I've had the honor of sharing space with it. Let's see how much longer we both last!

Santiago de los Caballeros is in use today. It's served by the same priest who gives mass in neighboring San Claudio de Olivares. It has endured the ravages of weather for about 900 years. For two years, I've had the honor of sharing space with it. Let's see how much longer we both last!

Published on May 31, 2019 09:05

May 15, 2019

A Lonely Place Made Sacred by Architecture and Paint: Medieval Soria

Looking for history in the middle of nowhere.

Looking for history in the middle of nowhere.Photos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss Our epic journey through the province of Soria in early March meant Daniel and I were often confronted with vast expanses of rolling Castilian plains. Sometimes, if you subtracted the asphalt roads, you would've been left with no sign of human life at any point in history--unless you knew exactly where to look.

Daniel had designed the itinerary so that the Church of San Baudelio near Casillas de Berlanga would dominate one of the trip days. As usual, though, there was too much to see! I'm thrilled we didn't skip Almazán, but taking that tour meant we had to rush to San Baudelio before it closed for the day. It seemed as if we would never make it, as there was never any indication that we were getting closer to this magical building. It was first started as a hermitage in the middle of nowhere. You can't get more nowhere than Casillas de Berlanga--no offense intended.

Daniel had designed the itinerary so that the Church of San Baudelio near Casillas de Berlanga would dominate one of the trip days. As usual, though, there was too much to see! I'm thrilled we didn't skip Almazán, but taking that tour meant we had to rush to San Baudelio before it closed for the day. It seemed as if we would never make it, as there was never any indication that we were getting closer to this magical building. It was first started as a hermitage in the middle of nowhere. You can't get more nowhere than Casillas de Berlanga--no offense intended. The tiny box of a building (less than 10 square meters) that appears between hillocks as if conjured by a Spanish Merlin is often described as plain. Although I didn't get a chance to read about the architecture before the visit, the sight of the stones taken from the hillside where it sits and lots of medieval concrete resonated strongly with me. Indeed, as I read later, it is believed this church was erected shortly after this area was "reconquered" in the year 912. Which is to say that the structure is pre-Romanesque Mozarabic. This building was around, looking much as it does today, when the characters in Seven Noble Knights lived, fought, and loved.

The tiny box of a building (less than 10 square meters) that appears between hillocks as if conjured by a Spanish Merlin is often described as plain. Although I didn't get a chance to read about the architecture before the visit, the sight of the stones taken from the hillside where it sits and lots of medieval concrete resonated strongly with me. Indeed, as I read later, it is believed this church was erected shortly after this area was "reconquered" in the year 912. Which is to say that the structure is pre-Romanesque Mozarabic. This building was around, looking much as it does today, when the characters in Seven Noble Knights lived, fought, and loved.

As if that history weren't enough to give me the authorial tingles, we hurried inside to make the most of the time before the caretaker closed up. I had to take off my glasses because the transition lenses made it impossible to see anything in the light from three tiny windows and the caretaker was answering the questions of three or four visitors with their modern speech, clothes, and priorities.

As if that history weren't enough to give me the authorial tingles, we hurried inside to make the most of the time before the caretaker closed up. I had to take off my glasses because the transition lenses made it impossible to see anything in the light from three tiny windows and the caretaker was answering the questions of three or four visitors with their modern speech, clothes, and priorities. In spite of all that, the interior overwhelmed me with a sense of sacred awe. To go against my usual writing style and employ understatement, this is no ordinary tiny hillside hermitage. There is no other building like this in all the world.

In spite of all that, the interior overwhelmed me with a sense of sacred awe. To go against my usual writing style and employ understatement, this is no ordinary tiny hillside hermitage. There is no other building like this in all the world. As you walk in, you're confronted by a column that seems enormous because it draws the eye up and fills the field of vision. Eight fronds arc out at the top to complete a cupola that covers the entire space, encompassing it and all visitors within what would be the shade of this metaphorical palm tree. That's right, as you walk in, you face the Tree of Life, the Source of everything, physical and spiritual.

As you walk in, you're confronted by a column that seems enormous because it draws the eye up and fills the field of vision. Eight fronds arc out at the top to complete a cupola that covers the entire space, encompassing it and all visitors within what would be the shade of this metaphorical palm tree. That's right, as you walk in, you face the Tree of Life, the Source of everything, physical and spiritual. To the left of the entrance, so small you might miss it, a diminutive apse opens up with double horseshoe arches and lets light in with its small window. Here, the most sacred ceremonies, such as consecration, would have been carried out without the need for any congregation to witness. Only about four people can fit there with room to move.

To the left of the entrance, so small you might miss it, a diminutive apse opens up with double horseshoe arches and lets light in with its small window. Here, the most sacred ceremonies, such as consecration, would have been carried out without the need for any congregation to witness. Only about four people can fit there with room to move. In the center, an open space harbors altar tables and a stairway to the most unusual part of the building, the loft.

In the center, an open space harbors altar tables and a stairway to the most unusual part of the building, the loft.

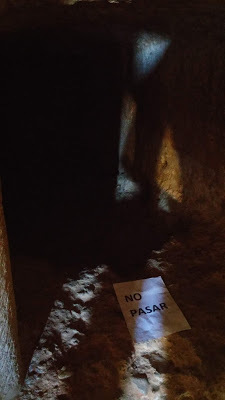

The loft enjoys a small window and a tiny chapel with room for only one person and its own two Mozarabic windows with horseshoe arches at the top. The loft is not accessible to the public, but it is clearly a place for contemplative isolation. The feature that makes this church unique also lends it tremendous spiritual gravity.

The loft enjoys a small window and a tiny chapel with room for only one person and its own two Mozarabic windows with horseshoe arches at the top. The loft is not accessible to the public, but it is clearly a place for contemplative isolation. The feature that makes this church unique also lends it tremendous spiritual gravity.

The loft is supported by a forest of miniature columns that come together in eleven horseshoe arches without capitals. Known as the "mosque," this collection of architecture only rises to a third of the building's height. It provides a daunting barrier between the rest of the building and the original hermitage cave entrance.

The loft is supported by a forest of miniature columns that come together in eleven horseshoe arches without capitals. Known as the "mosque," this collection of architecture only rises to a third of the building's height. It provides a daunting barrier between the rest of the building and the original hermitage cave entrance.  My fantastic photo of the cave entrance.

My fantastic photo of the cave entrance.Don't go in, the paper emphatically instructs.

Having taken in all that uniqueness, it's time to look up at the top of the palm tree again. Notice the hole between the branches. You think you're imagining it, but you can kind of see something architectural going on inside. You're not imagining it! There's a secret chamber up there! It's impractical to access and evokes the unstable border region this was when San Baudelio was built. Would it have been a place to hide valuables or even a hermit in case of attack?

Having taken in all that uniqueness, it's time to look up at the top of the palm tree again. Notice the hole between the branches. You think you're imagining it, but you can kind of see something architectural going on inside. You're not imagining it! There's a secret chamber up there! It's impractical to access and evokes the unstable border region this was when San Baudelio was built. Would it have been a place to hide valuables or even a hermit in case of attack?My descriptions and photos are falling short. The wonder San Baudelio induces is untranslatable.

These bulls are the original finished paintings!

These bulls are the original finished paintings!Photo 2019 Daniel Sanz And as you can see in the photos, there's still more to marvel at. We'd originally come for the extensive medieval paintings, as many guidebooks call this Soria's "Sistine Chapel." In accordance with medieval sensibilities, the artists among this community of monks left no space plain. They used a technique similar to fresco, so that the paint penetrates deep into the wall. In the early twentieth century, the outermost layers of some paintings were sold and removed. After some back and forth, these works of art can now be viewed in person in Madrid and New York. I'd seen them already in the museums and loved them with no knowledge of where they came from. There is nothing like viewing this art in its original context.

I remember seeing this rabbit hunting scene in the Museo del Prado in 2005. The imprints left behind are still so vivid, the visitor gets most of the intended impact. The central column is dotted to suggest a palm trunk. The branches are covered in colorful geometric and architectural patterns with long-necked birds that call San Pedro de la Nave to mind.

I remember seeing this rabbit hunting scene in the Museo del Prado in 2005. The imprints left behind are still so vivid, the visitor gets most of the intended impact. The central column is dotted to suggest a palm trunk. The branches are covered in colorful geometric and architectural patterns with long-necked birds that call San Pedro de la Nave to mind. The higher areas and loft feature remnants of Biblical scenes with people and tables.

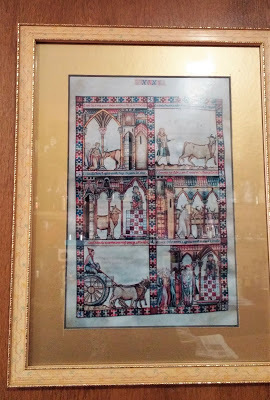

The higher areas and loft feature remnants of Biblical scenes with people and tables. The area above the stairs has painted drapery and medallions with animal figures.

The area above the stairs has painted drapery and medallions with animal figures. The entrance to the apse shows angels supporting a medallion with the Dextera Domini, the right hand of the Lord.

The entrance to the apse shows angels supporting a medallion with the Dextera Domini, the right hand of the Lord.

The apse is filled with saints and Biblical scenes and a dove, the Holy Spirit, springs forth from the window, as I'd seen in Maderuelo.

The apse is filled with saints and Biblical scenes and a dove, the Holy Spirit, springs forth from the window, as I'd seen in Maderuelo. Warrior on the side of the loft chapel. During the visit, I was under the impression that all the paintings were Romanesque, from the eleventh century onward. But according to Jaime Cobreros, many discreet scenes may be from the earliest times of the church's existence, the tenth century. The possibly earlier paintings are less obviously religious in nature and show some artistic connection with Hispano-Muslim art and Beatus manuscript illustration. These include some lions; the hunting scene, a camel, a rampant greyhound, and the warrior with shield on the side of the loft chapel, all now in the Prado; and the magnificent bulls pictured above. I couldn't believe no one had bought the top layer of the bulls painting, and had Daniel take my photo with it so I could pretend it was mine.

Warrior on the side of the loft chapel. During the visit, I was under the impression that all the paintings were Romanesque, from the eleventh century onward. But according to Jaime Cobreros, many discreet scenes may be from the earliest times of the church's existence, the tenth century. The possibly earlier paintings are less obviously religious in nature and show some artistic connection with Hispano-Muslim art and Beatus manuscript illustration. These include some lions; the hunting scene, a camel, a rampant greyhound, and the warrior with shield on the side of the loft chapel, all now in the Prado; and the magnificent bulls pictured above. I couldn't believe no one had bought the top layer of the bulls painting, and had Daniel take my photo with it so I could pretend it was mine. Photo 2019 Daniel Sanz Outside the church, you think, "All that is in there?"

Photo 2019 Daniel Sanz Outside the church, you think, "All that is in there?" Then you take a look at the archaeological site of the medieval necropolis. Just outside the apse, they've found thirty sarcophagi from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries that were probably used even a bit after that. Monks burying monks.

Then you take a look at the archaeological site of the medieval necropolis. Just outside the apse, they've found thirty sarcophagi from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries that were probably used even a bit after that. Monks burying monks. On the other side, there's a modest, modern spout that marks the spot where the first hermit found a water source so he could live out here all alone, and which was exploited by the monks who followed him.

On the other side, there's a modest, modern spout that marks the spot where the first hermit found a water source so he could live out here all alone, and which was exploited by the monks who followed him.We still have the building and paintings unaltered today because the church became neglected after the thirteenth century. No more monks wanted to live way out here, and so no one was around to make changes with new architectural fads.

And that was it. We enjoyed this unforgettable place for only about 40 minutes before the caretaker closed up. We had to leave to make it to our lunch reservation in Berlanga del Duero, in any case. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak!

Our visit was similar to San Baudelio's history: a brief, shining artistic moment, never to be imitated anywhere else.

Our visit was similar to San Baudelio's history: a brief, shining artistic moment, never to be imitated anywhere else. On the way home to Zamora, I was reading some of the pamphlets we picked up on this epic trip and discovered that in Berlanga del Duero, there's an entire museum devoted to San Baudelio. Sigh. Next time. Meanwhile, many scholars have published articles and photos on San Baudelio, as a simple internet search reveals. Daniel and I are far from the only San Baudelio nerds in the world.

On the way home to Zamora, I was reading some of the pamphlets we picked up on this epic trip and discovered that in Berlanga del Duero, there's an entire museum devoted to San Baudelio. Sigh. Next time. Meanwhile, many scholars have published articles and photos on San Baudelio, as a simple internet search reveals. Daniel and I are far from the only San Baudelio nerds in the world.

Published on May 15, 2019 15:31

May 9, 2019

Puebla de Sanabria: Untouched by Time

Puebla de Sanabria on its rocky outcrop over the Tera

Puebla de Sanabria on its rocky outcrop over the Tera juts into the tourist's imagination.

Photos in this post 2018 and 2019 Jessica Knauss It was the winter low season in Puebla de Sanabria, with no festivals or pilgrimages scheduled for months, but my traveling companion, Daniel, felt lucky to grab the last available one-star hotel room in the historical center. Puebla is one of the official Most Beautiful Villages in Spain, a France-inspired list that began in 2011 as a way to promote rural tourism. It’s working.

Still can't get inside.

Still can't get inside.Photo 2019 Daniel Sanz We’d come to see Romanesque buildings, but quickly found that the churches on my bucket list were closed for visits until Easter week. We were left with buying souvenirs or walking among the pristine streets to admire the popular architecture.

It wasn’t a bad consolation prize, because aside from the occasional car and a dragon-faced rainspout the residents couldn’t resist, the old town of Puebla looks as it must have in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Tawny stones fit together in pleasant haphazard puzzles, noble crests adorn palaces, and extended eaves and colonnades provide shelter from wet weather. We aren’t the only visitors to get the sense that this is a place untouched by time.

It wasn’t a bad consolation prize, because aside from the occasional car and a dragon-faced rainspout the residents couldn’t resist, the old town of Puebla looks as it must have in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Tawny stones fit together in pleasant haphazard puzzles, noble crests adorn palaces, and extended eaves and colonnades provide shelter from wet weather. We aren’t the only visitors to get the sense that this is a place untouched by time. The view from the castle After the climb to the robust, legend-filled castle at the top of Puebla’s dramatic rocky outcrop, we stood at the gusty vista point to gaze down at the river and newer part of town below. We read a plaque that advocates a tenuous connection between this place and Miguel de Cervantes, then headed west on streets lustrous with slate paving beneath balconies made of hand-carved wood.

The view from the castle After the climb to the robust, legend-filled castle at the top of Puebla’s dramatic rocky outcrop, we stood at the gusty vista point to gaze down at the river and newer part of town below. We read a plaque that advocates a tenuous connection between this place and Miguel de Cervantes, then headed west on streets lustrous with slate paving beneath balconies made of hand-carved wood.

It wasn’t long before we arrived at the other side of the rock, a parapet facing a green valley and the setting sun. A line of yet more historical homes cozied up to the bottom of the rock, but one caught our attention because the roof, near our eye level, was a timber grid, and stacks of slate tiles awaited placement.

It wasn’t long before we arrived at the other side of the rock, a parapet facing a green valley and the setting sun. A line of yet more historical homes cozied up to the bottom of the rock, but one caught our attention because the roof, near our eye level, was a timber grid, and stacks of slate tiles awaited placement. Slate roof “They’re really doing that up right,” said Daniel. “It’ll fit in with the other houses, and it’ll last forever.”

Slate roof “They’re really doing that up right,” said Daniel. “It’ll fit in with the other houses, and it’ll last forever.” New "old" construction. A cat darted across the parapet, shooed by a woman in house slippers and a T-shirt farther down the street. “Sorry,” she said as we approached. “The cats get into my plants!”

New "old" construction. A cat darted across the parapet, shooed by a woman in house slippers and a T-shirt farther down the street. “Sorry,” she said as we approached. “The cats get into my plants!” Pots and vases covered the parapet in front of her house, which she said they’d built in the 80s with high hopes. “It’s really big,” she said. “It’s only this wide, but goes way back, and it has two stories and the attic, which we were allowed to build because the house that was here before had one.”

Pots and vases covered the parapet in front of her house, which she said they’d built in the 80s with high hopes. “It’s really big,” she said. “It’s only this wide, but goes way back, and it has two stories and the attic, which we were allowed to build because the house that was here before had one.”“This was only built in the 80s? It looks much more historical,” said Daniel.

“The city makes us use traditional materials. See, the window frames are wooden. The sun batters the façade in the summer—it gets to be 40 degrees Celsius right here.” I believed her. At sunset in February, my jacket already felt heavy. “And in the winter, the frost comes and splits the wood, no matter how hard it is.”

“The city makes us use traditional materials. See, the window frames are wooden. The sun batters the façade in the summer—it gets to be 40 degrees Celsius right here.” I believed her. At sunset in February, my jacket already felt heavy. “And in the winter, the frost comes and splits the wood, no matter how hard it is.” “They make PVC that looks a lot like wood now,” said Daniel.

“They make PVC that looks a lot like wood now,” said Daniel.“I wish I could use PVC, but the city won’t let me. It has to be authentic for the tourists.”

Black mascara that must’ve once matched her hair color ran down her cheeks in the tracks of old tears. Her husband had passed away five years before. The children had all moved away, one as far as Valencia. They encouraged their mother to convert the grand family inheritance into a hotel, like many of the other homes in the old town. Otherwise, it was headed for neglect and ruin, with no one there to care for it. It looked as if the woman wanted to tell us she would live forever to personally take care of this legacy.

When we said our goodbyes and moved on, I spied the shadow of someone waiting for the woman at the end of the hall. A sister or cousin, as bent by time as she, hadn’t made it into her loneliness narrative. But I was relieved she had some company in her battle against the two fronts of history and progress. Puebla de Sanabria is touched by time, after all.

When we said our goodbyes and moved on, I spied the shadow of someone waiting for the woman at the end of the hall. A sister or cousin, as bent by time as she, hadn’t made it into her loneliness narrative. But I was relieved she had some company in her battle against the two fronts of history and progress. Puebla de Sanabria is touched by time, after all.

Published on May 09, 2019 02:36

April 29, 2019

Visigoths in Palencia! San Juan de Baños

San Juan de Baños

San Juan de BañosAll photos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss It might cheapen the effect to give you the money shot of this lovely historical building right at the top of the post. In reality, it's not something a casual traveler stumbles upon. Like most Visigothic monuments, San Juan de Baños is in a tiny locality not known for any other reason. I had to randomly hear about this, the only Visigothic church with a firm date, figure out where the heck Baños de Cerrato is, and then wait until I found a friend as crazy as I am about historical-themed road trips to take me there. Overall, there is a high risk of spending your time in the unique, fascinating small city of Palencia, never knowing what you missed.

San Juan de Baños has the feeling of being nowhere,

San Juan de Baños has the feeling of being nowhere, but it's right next to an industrial area. This church is in this location for a specific reason. In January 661, King Reccesvinthus was returning to Toledo from fighting rebellious Basque tribes in the north and feeling rather poorly, as you well might in the early Middle Ages. The cortege stopped in Balneos (now Baños de Cerrato) because someone had heard of the curative waters there. It had been a spa town since Roman times. Reccesvinthus drank the water and felt much better. This miracle inspired him to found a water/baptism-themed church in that very spot.

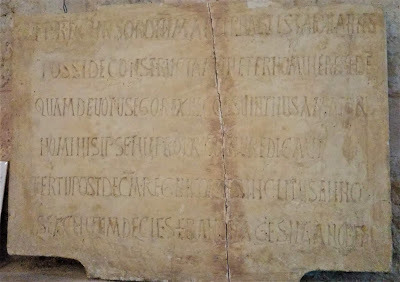

The original dedication stone is up high and decorated with sunbursts. The church still proudly displays the stone on which Reccesvinthus inscribed his dedication of the church:

The original dedication stone is up high and decorated with sunbursts. The church still proudly displays the stone on which Reccesvinthus inscribed his dedication of the church: A replica of the dedication stone is set where visitors can read it. "The precursor of the Lord, the martyr Saint John the Baptist, owns this house, built as an eternal gift that I, King Reccesvinthus, devout worshiper of your name, dedicated to you, by my own right, in the third year after the tenth as illustrious companion of this kingdom. In the year 661."

A replica of the dedication stone is set where visitors can read it. "The precursor of the Lord, the martyr Saint John the Baptist, owns this house, built as an eternal gift that I, King Reccesvinthus, devout worshiper of your name, dedicated to you, by my own right, in the third year after the tenth as illustrious companion of this kingdom. In the year 661." Water quality is not guaranteed. That didn't stop my friend! The fountain has fallen into disrepair and been rebuilt many times since Reccesvinthus's time, but the spring water has never stopped flowing. The latest reconstruction is from the 1940s, with two horseshoe arches that echo the architecture of the church.

Water quality is not guaranteed. That didn't stop my friend! The fountain has fallen into disrepair and been rebuilt many times since Reccesvinthus's time, but the spring water has never stopped flowing. The latest reconstruction is from the 1940s, with two horseshoe arches that echo the architecture of the church. Most of the stones here and especially the horseshoe arch

Most of the stones here and especially the horseshoe arch were put together in 661! The building itself is in a remarkable state of conservation. The bell gable was added in 1865. Apart from that, the only extant features that are not from 661 are the roof, the jalousies (lacy stone window panes that must be modeled on pre-Romanesque buildings I adore in Oviedo), and the floor.

The geometric floral friezes in the door will be echoed inside.

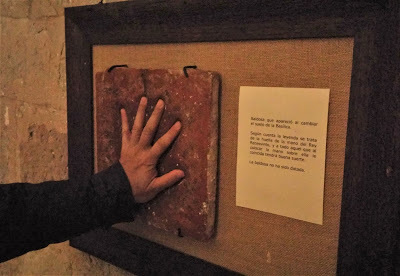

The geometric floral friezes in the door will be echoed inside.  Archaeologists took advantage of the rehabilitation of the floor to dig around and find many wonderful items that are now housed in the Museum of Palencia, such as Visigothic burials and a curious tile. It showed up in the excavations with an imperious hand print, giving rise to the legend that it was Reccesvinthus's way of signing the church he ordered to be built. Whosoever possesseth a hand that fitteth into the impression exactly shall be named new King of the Visigoths. As you can see, my friend is now King Daniel of the Visigoths. I tried too, but my pinkie was too short. The page pictured next to the replica says only that a perfect fit will give the hand's owner good luck. I guess they're not ready to hand the crown over, even though the kingdom no longer exists!

Archaeologists took advantage of the rehabilitation of the floor to dig around and find many wonderful items that are now housed in the Museum of Palencia, such as Visigothic burials and a curious tile. It showed up in the excavations with an imperious hand print, giving rise to the legend that it was Reccesvinthus's way of signing the church he ordered to be built. Whosoever possesseth a hand that fitteth into the impression exactly shall be named new King of the Visigoths. As you can see, my friend is now King Daniel of the Visigoths. I tried too, but my pinkie was too short. The page pictured next to the replica says only that a perfect fit will give the hand's owner good luck. I guess they're not ready to hand the crown over, even though the kingdom no longer exists! The main altar. The wooden roof is made to

The main altar. The wooden roof is made to look as it might have in Visigothic times. When you enter, the space is not large, but the simple lines of construction produce a sense of vastness. Horseshoe arches dominate the scene, proving that the Iberian Peninsula did not have to wait until the Arabs and Berbers took over in order to grace its buildings with this pleasing shape. We see them in the grand arch of the main altar, the windows, and between eight columns.

The guide says the lateral arches are slightly irregular, but you would really have to look to spot the flaws. The impression is of stately harmony.

The guide says the lateral arches are slightly irregular, but you would really have to look to spot the flaws. The impression is of stately harmony. The marble columns have been harvested from Roman villas that have long since disappeared. Most if not all the stones used in the rest of the church are also likely recycled from Roman buildings. In this way, the Roman legacy has come down to us today, only slightly altered.

The marble columns have been harvested from Roman villas that have long since disappeared. Most if not all the stones used in the rest of the church are also likely recycled from Roman buildings. In this way, the Roman legacy has come down to us today, only slightly altered. The recycled Roman capital is right next to the main altar. One Corinthian column capital has been identified as a late Roman carving based solely on its style.

The recycled Roman capital is right next to the main altar. One Corinthian column capital has been identified as a late Roman carving based solely on its style. The other capitals are also Corinthian style, but the execution is less ornate. The guide seemed to think the Visigothic artisans were unable to produce the same level of detail as their direct Roman forebears. Having studied the purposeful simplicity of Romanesque art as contrasted with the complexities of the Gothic area, I appreciate the clean lines of the Visigothic capitals and believe the differences between them and the Roman one are due to taste.

The other capitals are also Corinthian style, but the execution is less ornate. The guide seemed to think the Visigothic artisans were unable to produce the same level of detail as their direct Roman forebears. Having studied the purposeful simplicity of Romanesque art as contrasted with the complexities of the Gothic area, I appreciate the clean lines of the Visigothic capitals and believe the differences between them and the Roman one are due to taste. I especially like this capital because the interpretation of the Corinthian pattern is so free, and because the diminutive four-petaled flower in the center inserts the new Christian symbolism into an ancient context.

I especially like this capital because the interpretation of the Corinthian pattern is so free, and because the diminutive four-petaled flower in the center inserts the new Christian symbolism into an ancient context. Lest we think the ancient and medieval world was all bare stone, the guide was careful to point out the paint traces. Medieval people did not want to look at their construction materials in their finished edifices any more than we would want to stare at rebar or insulation. They filled their buildings with color and shapes! Here you can also appreciate the geometric flower friezes, repeated throughout the building, inside and out. Interest, focal points, horror vacui, it's all here, in this seemingly simple space.

Lest we think the ancient and medieval world was all bare stone, the guide was careful to point out the paint traces. Medieval people did not want to look at their construction materials in their finished edifices any more than we would want to stare at rebar or insulation. They filled their buildings with color and shapes! Here you can also appreciate the geometric flower friezes, repeated throughout the building, inside and out. Interest, focal points, horror vacui, it's all here, in this seemingly simple space. In keeping with the baptism theme, San Juan de Baños boasts an ancient baptismal font, exactly the kind of thing I imagine Mudarra using in Seven Noble Knights. The lack of decoration makes it hard to date, but the guide said the best guess places it between the fifth and sixth centuries. Adults would have stripped down and stepped right in to be initiated into the Christian church.

In keeping with the baptism theme, San Juan de Baños boasts an ancient baptismal font, exactly the kind of thing I imagine Mudarra using in Seven Noble Knights. The lack of decoration makes it hard to date, but the guide said the best guess places it between the fifth and sixth centuries. Adults would have stripped down and stepped right in to be initiated into the Christian church. A replica of Reccesvinthus's votive crown is hanging in the space it was probably meant for. I've seen the original at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid and admired the fine metalwork and precious jewels. The sight of the replica in situ moved me deeply.

A replica of Reccesvinthus's votive crown is hanging in the space it was probably meant for. I've seen the original at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid and admired the fine metalwork and precious jewels. The sight of the replica in situ moved me deeply.San Juan de Baños is consecrated, but is only used for visits like this and for weddings. It would be an exceptionally elegant place to say vows, in my humble opinion.

The foot of the church with the door

The foot of the church with the door and the guide's station.

Palencia is the host of one more of these rare pieces of Visigothic architecture, and it has another legend attached to its founding, so check this space for more!

Published on April 29, 2019 10:56

April 27, 2019

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Holy Week 2019

Tuesday night of Holy Week

Tuesday night of Holy WeekJessica Knauss 2019 I honestly thought that, this being my second Holy Week in Zamora, I could maintain a more distanced perspective on this apotheosis of folklore, popular religion, and art. I figured I'd pick up the processions I missed last year and the week would be mostly normal, a proper rest during which I could probably get some writing done.

How quickly we forget!

Last year, I had to skip the Friday of Sorrows procession of the Penitential Brotherhood of the Most Holy Christ of the Holy Spirit because the weather was terrible. Being the first late-night procession, I didn't know what I was missing and so didn't have the wherewithal to trek across Zamora in the nighttime wind and rain. This year, I arrived early enough to catch the perfect spot at the iron fence around the cathedral atrium, early enough to watch several TV crews setting up. And still I thought it would be no big deal.

The cathedral plaza filled with enthusiasts, and the air became thick with expectancy. The choir assembled in the atrium, and one of the choristers even came out to the fence where I was to chat with his girlfriend. And then the first brotherhood members appeared in their white monklike hoods with the first "float" an intensely heavy bell that rang loud enough to imbue everything with medieval-tinged magic.

Holy Week magic was back!

I couldn't miss anything from then on. I saw every procession I missed last year and tried to revisit old favorites to a memorable, soggy conclusion. I saw colors, smelled incense, and above all, heard amazing music.

I'd booked a trip to Palencia when I was still thinking I would be more blasé about Zamoran Holy Week, and managed to catch a procession there, too. Amazing to compare to two cities' Holy Saurday traditions.

The trip to Palencia was well worth it, and you will see some gems from that medieval province on this blog.

I've now seen every single one of the processions already (some of them twice), so trust me, there's no way I'll lose my head over the magic of Holy Week again. (Hmmm...)

To round out your experience of Holy Week in Zamora, visit last year's post and last year's anticipatory post.

Published on April 27, 2019 09:50

April 2, 2019

Romanesque with a Twist: Almazán, Soria

Twelfth-century San Miguel in Almazán

Twelfth-century San Miguel in AlmazánAll photos in this post 2019 Jessica Knauss I'd been too satisfied with our visit to Almenar to think about much else, but Daniel said, "We have to visit Almazán. Trust me." He was using a guidebook to the "best" Romanesque sites in Spain, and it was turning out to be highly reliable, and really, I'm content with any vaguely medieval site you can show me, so of course I didn't object.

What are some good adjectives for Almazán? Twisted. Skewed. Awry. Catawumpus. Cockeyed.

How so? The above photo is the plaza where we parked. Notice anything unusual?

How so? The above photo is the plaza where we parked. Notice anything unusual?But let's allow the Romanesque Church of San Miguel to fully illustrate this idea.

San Miguel is in the enormous Plaza Mayor, where the Palace of the Counts of Altamira serves as the tourism office. There you buy your ticket for the church tour. We had many other wonders on our itinerary that day, so we hesitated. I'm so glad we stayed.