Jessica Knauss's Blog, page 8

June 25, 2018

Valladolid's Medieval Treasures: Wamba

King Wamba in a 2009 statue in ... Wamba

King Wamba in a 2009 statue in ... WambaAll photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss

unless otherwise specified. The province of Valladolid is densely packed with unique cultural and historical monuments. Exploring it this winter, I zipped past signage for a place called Wamba several times. I thought it sounded interesting because there had been a Visigothic king by that name. Finally, I saw a photo of the interior of its parish church in a tourism brochure and knew I had to go there right away.

Sure enough, driving up to what seems to be any other town in the province, I saw that Wamba proclaims its difference with a statue in honor of its namesake. I like the rough carving style. It looks almost spongy, as if you could give this king, who reigned from 672 to 680, a big, squishy hug.

A Roman capital repurposed in the tenth century to

A Roman capital repurposed in the tenth century tocontain holy water in Wamba's church

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón He provokes that reaction in me because I take a liking to all leaders who fulfill their roles out of a sense of duty rather than ambition. The Visigoths controlled the Iberian Peninsula from the middle of the fifth century (the "Fall of Rome") to 711 AD. The position of King of the Visigoths wasn't necessarily hereditary. You had to be elected king, and God help you if you were. Wamba's eight-year reign was one of the longest, and many kings were assassinated to make way for the next.

Parish church of St. Mary of the O, Wamba There are many legends concerning Wamba's rise to power, all stemming from the idea that he would rather have continued to work on his farm than go to Toledo and make state decisions. That's what he told the councilors when they went to tell him he'd been declared king. The councilors insisted, and many legends say Wamba shoved a dry stick in the ground, declaring that if it took root and grew, he would go to Toledo with them. Whether because of the miracle of the dry stick or because the councilors were convincing (even threatening his life if he didn't accept), Wamba relented in the town that now bears his name.

Parish church of St. Mary of the O, Wamba There are many legends concerning Wamba's rise to power, all stemming from the idea that he would rather have continued to work on his farm than go to Toledo and make state decisions. That's what he told the councilors when they went to tell him he'd been declared king. The councilors insisted, and many legends say Wamba shoved a dry stick in the ground, declaring that if it took root and grew, he would go to Toledo with them. Whether because of the miracle of the dry stick or because the councilors were convincing (even threatening his life if he didn't accept), Wamba relented in the town that now bears his name. It may not be terribly compelling from the outside... just wait! His reign was typically fraught with enemies foreign and domestic, and after making some controversial military and religious reforms, in 680, Wamba fell ill (or was poisoned) and received the order of penance, effectively ending his kingship. When he recovered, he went into seclusion to live out his final years. The guide at the parish church told a different version: Wamba's successor, Erwig, had his men jump Wamba and force a penitent's habit over his head. Because no king could legally wear such robes, that ended his reign, no poison or illness needed.

It may not be terribly compelling from the outside... just wait! His reign was typically fraught with enemies foreign and domestic, and after making some controversial military and religious reforms, in 680, Wamba fell ill (or was poisoned) and received the order of penance, effectively ending his kingship. When he recovered, he went into seclusion to live out his final years. The guide at the parish church told a different version: Wamba's successor, Erwig, had his men jump Wamba and force a penitent's habit over his head. Because no king could legally wear such robes, that ended his reign, no poison or illness needed. Wamba town hall When my partner in historical adventures and I drove up to the parish church, it was shut tight. A sign on the door indicated we should call a number to alert the guide to our presence. We didn't see any number to call. We walked to the town hall, and it was also shuttered on a nippy Saturday in March.

Wamba town hall When my partner in historical adventures and I drove up to the parish church, it was shut tight. A sign on the door indicated we should call a number to alert the guide to our presence. We didn't see any number to call. We walked to the town hall, and it was also shuttered on a nippy Saturday in March. There was a pair of men hanging around across the square, so we asked them what to do. They kindly directed us to go down the street and hang a left at the new brick building—it was obvious what they meant in the context of the old bricks near the church—to knock on the guide's door. Along the way we saw several examples of crosses having been encased in walls as pictured, but we never got the chance to ask what it might mean. The guide knew what we wanted without our having to say. When she joined us back at the church door, she asked why we walked over instead of calling, and of course that's when the number jumped out at us at the top of the page.

There was a pair of men hanging around across the square, so we asked them what to do. They kindly directed us to go down the street and hang a left at the new brick building—it was obvious what they meant in the context of the old bricks near the church—to knock on the guide's door. Along the way we saw several examples of crosses having been encased in walls as pictured, but we never got the chance to ask what it might mean. The guide knew what we wanted without our having to say. When she joined us back at the church door, she asked why we walked over instead of calling, and of course that's when the number jumped out at us at the top of the page.We were trendsetters. After the tour started, several more couples walked in and wanted to join us. I'm glad Wamba is attracting a few visitors.

"Recceswinth's tomb" in the church's back garden It's said that the parish church in Wamba rests on the site of a seventh-century Visigothic monastery where Wamba's predecessor, Recceswinth, died and was buried.

"Recceswinth's tomb" in the church's back garden It's said that the parish church in Wamba rests on the site of a seventh-century Visigothic monastery where Wamba's predecessor, Recceswinth, died and was buried.

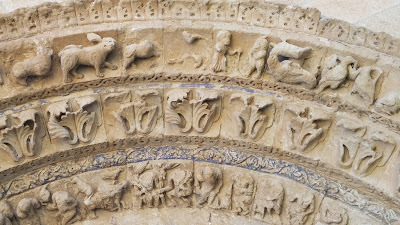

Its ancient nature, with architectural styles from different periods overlapping and vying for supremacy, is evident in this facade, where we see Zamora-influenced Romanesque bestiary corbels and arches under a Renaissance gable and the date 1233 (meaning 1195) inscribed with flowers that represent the four gospels.

Its ancient nature, with architectural styles from different periods overlapping and vying for supremacy, is evident in this facade, where we see Zamora-influenced Romanesque bestiary corbels and arches under a Renaissance gable and the date 1233 (meaning 1195) inscribed with flowers that represent the four gospels.  We can still find the remains of twelfth-century paint under the arches, where it's protected from the elements. Don't ever let anyone tell you the Middle Ages were all brown, grey, and black.

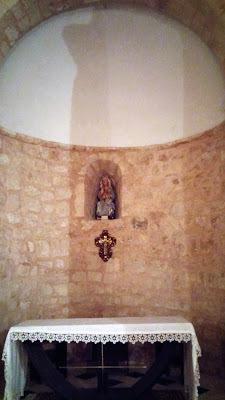

We can still find the remains of twelfth-century paint under the arches, where it's protected from the elements. Don't ever let anyone tell you the Middle Ages were all brown, grey, and black. Tenth-century apse/main altar of the parish church While no traces have been found of a Visigothic construction, the current church originated with the founding of a Mozarabic monastery in 928. Little documentary evidence exists about the church in these early times, and even less about its construction, but the gorgeous apse cannot lie: it was erected in the tenth century. More than a thousand years fall away as we contemplate the perfect horseshoe arch, the low vaulted ceiling, and the closed-off nature of the main altar. Full disclosure: the Mozarabic vaulting in this part of the apse was redone in the twelfth century, but the Romanesque architects followed the original lines.

Tenth-century apse/main altar of the parish church While no traces have been found of a Visigothic construction, the current church originated with the founding of a Mozarabic monastery in 928. Little documentary evidence exists about the church in these early times, and even less about its construction, but the gorgeous apse cannot lie: it was erected in the tenth century. More than a thousand years fall away as we contemplate the perfect horseshoe arch, the low vaulted ceiling, and the closed-off nature of the main altar. Full disclosure: the Mozarabic vaulting in this part of the apse was redone in the twelfth century, but the Romanesque architects followed the original lines. The wall behind the main altar features these precious "proto-Romanesque" paintings in black and red with a cross and animals in geometrically decorated circles. Imagine how brilliant these must have been before they were lime-and-chalked over!

The wall behind the main altar features these precious "proto-Romanesque" paintings in black and red with a cross and animals in geometrically decorated circles. Imagine how brilliant these must have been before they were lime-and-chalked over!

The hefty, angular column capitals based on plant motifs are tenth-century Mozarabic. They betray strong ties to their Classical predecessors, but you could never confuse the two styles.

The hefty, angular column capitals based on plant motifs are tenth-century Mozarabic. They betray strong ties to their Classical predecessors, but you could never confuse the two styles.

The side chapels, with their horseshoe arches and closed-off feeling, are also from the 928 founding. They recall San Pedro de la Nave so strongly that you could've fooled me into believing they were the remains of the legendary Visigothic monastery. These two architectural periods show continuity rather than competition. Come back when I post about San Cebrián de Mazote to learn the possible reason for the imperfections in the second chapel's archways.

The side chapels, with their horseshoe arches and closed-off feeling, are also from the 928 founding. They recall San Pedro de la Nave so strongly that you could've fooled me into believing they were the remains of the legendary Visigothic monastery. These two architectural periods show continuity rather than competition. Come back when I post about San Cebrián de Mazote to learn the possible reason for the imperfections in the second chapel's archways.

The nave is divided into three spaces by glorious twelfth-century Romanesque arches with slight points supported on pillars with ball decorations, which are topped with delightful Romanesque capitals. The ceiling has been restored to look as it did in Romanesque times. They say the window at the back illuminates the main altar spectacularly during late services.

The nave is divided into three spaces by glorious twelfth-century Romanesque arches with slight points supported on pillars with ball decorations, which are topped with delightful Romanesque capitals. The ceiling has been restored to look as it did in Romanesque times. They say the window at the back illuminates the main altar spectacularly during late services.

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón The tombs on each side are Gothic, from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The fifteenth-century tomb has a lovely Flemish depiction of the Visitation with a pink castle in the background. The sixteenth-century tomb has an entire altarpiece with Biblical scenes and saints under its Gothic tracery.

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón The tombs on each side are Gothic, from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The fifteenth-century tomb has a lovely Flemish depiction of the Visitation with a pink castle in the background. The sixteenth-century tomb has an entire altarpiece with Biblical scenes and saints under its Gothic tracery. Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón As in many of the churches in Zamora, in Wamba all the Romanesque column capitals are delightfully different. Here, near the main altar, we see what looks for all the world like a monkey sticking out his enormous ghastly tongue. I'm glad the guide pointed out the scissors on this side, and the shoe on the figure's left. This is a shoemaker, gnawing on leather to soften it. This depiction, humorous as it seems today, likely means the shoemakers guild gave money for the twelfth-century renovations.

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón As in many of the churches in Zamora, in Wamba all the Romanesque column capitals are delightfully different. Here, near the main altar, we see what looks for all the world like a monkey sticking out his enormous ghastly tongue. I'm glad the guide pointed out the scissors on this side, and the shoe on the figure's left. This is a shoemaker, gnawing on leather to soften it. This depiction, humorous as it seems today, likely means the shoemakers guild gave money for the twelfth-century renovations. Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón Across from the shoemaker, flanking the main chapel, we have a potter working on an urn with his head improbably turned 180 degrees to look at his companion, a shepherd. Everyone pitched in for the Romanesque construction!

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón Across from the shoemaker, flanking the main chapel, we have a potter working on an urn with his head improbably turned 180 degrees to look at his companion, a shepherd. Everyone pitched in for the Romanesque construction! Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón Elsewhere, two fantastic birds drink out of the same goblet, a symbolic theme we've seen on this blog a few times already in San Pedro de la Nave and San Claudio de Olivares in Zamora. The theme shows great continuity across space and time.

Photo 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón Elsewhere, two fantastic birds drink out of the same goblet, a symbolic theme we've seen on this blog a few times already in San Pedro de la Nave and San Claudio de Olivares in Zamora. The theme shows great continuity across space and time. This central column capital shows the Weighing of the Souls. Note the Devil pulling to swing the balance in his favor. The soul even looks a bit distressed about it!

This central column capital shows the Weighing of the Souls. Note the Devil pulling to swing the balance in his favor. The soul even looks a bit distressed about it! I'm not sure what this represents, but it looks like a pleasant skull and crossbones. This idea will come into play before we leave Wamba.

I'm not sure what this represents, but it looks like a pleasant skull and crossbones. This idea will come into play before we leave Wamba. This column is capped by an elephant and another exotic beast the sculptors likely never saw in person. For that reason, it's so general it's impossible to tell what it's supposed to be.

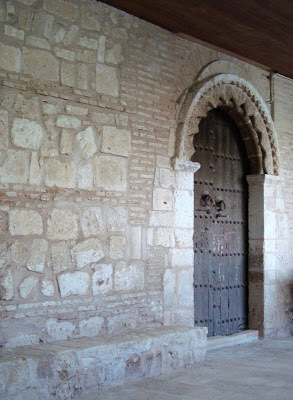

This column is capped by an elephant and another exotic beast the sculptors likely never saw in person. For that reason, it's so general it's impossible to tell what it's supposed to be. After gawking at all the capitals, the guide took us out to see this side door, which used to be the front door in Mozarabic times.

After gawking at all the capitals, the guide took us out to see this side door, which used to be the front door in Mozarabic times. There's an odd, floor-to-ceiling pillar in front of the tenth-century door. Since it accompanies the door, one could be forgiven for thinking it's been eroded over so many years—but one would be wrong. The sectional technique here is naturalistic, presaging Antoni Gaudí by about a thousand years. It's meant to evoke a palm tree. The palm tree's fruit, the date, signified divinity in the Mozarabic symbolic system.

There's an odd, floor-to-ceiling pillar in front of the tenth-century door. Since it accompanies the door, one could be forgiven for thinking it's been eroded over so many years—but one would be wrong. The sectional technique here is naturalistic, presaging Antoni Gaudí by about a thousand years. It's meant to evoke a palm tree. The palm tree's fruit, the date, signified divinity in the Mozarabic symbolic system.

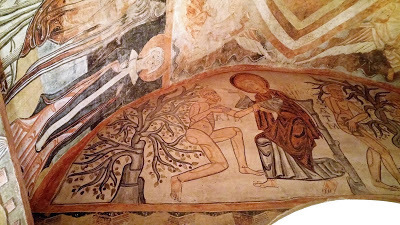

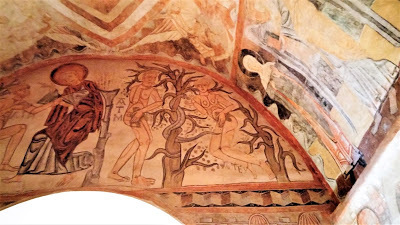

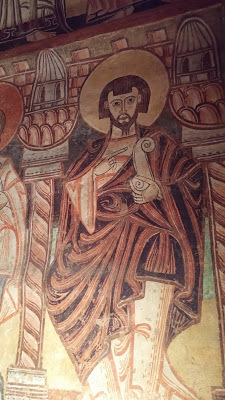

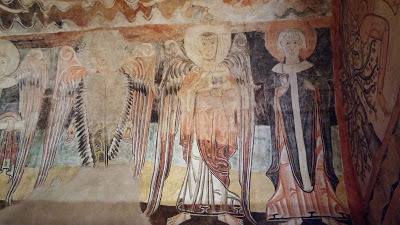

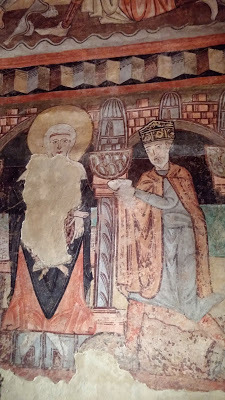

The chapel-like space behind the palm trunk and under the bell tower is filled with fourteenth-century linear Gothic paintings depicting the life of John the Baptist. This saint became important when Doña Sancha, sister of Alfonso VII, donated lands to the church, which was then known as Santa Maria de Bamba. The spelling was changed to Wamba in 1910 to better reflect its namesake, but the locals still pronounce it with a voiced bilabial stop (b), as if it were part of the lyrics to Ritchie Valens's most popular song.

The chapel-like space behind the palm trunk and under the bell tower is filled with fourteenth-century linear Gothic paintings depicting the life of John the Baptist. This saint became important when Doña Sancha, sister of Alfonso VII, donated lands to the church, which was then known as Santa Maria de Bamba. The spelling was changed to Wamba in 1910 to better reflect its namesake, but the locals still pronounce it with a voiced bilabial stop (b), as if it were part of the lyrics to Ritchie Valens's most popular song. The osario looks unassuming from the outside...

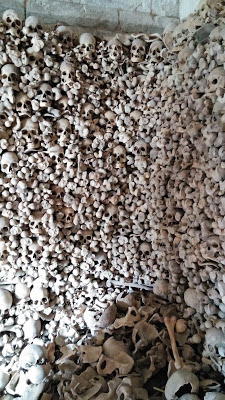

The osario looks unassuming from the outside...(It's only the small chamber behind the leftmost door.) I'm fluent in Spanish, but, thankfully, it continues to surprise me. There was talk on the tour and in signage about an osario. Misguided by a verb I thought I saw in the root of that word, I couldn't figure out what in the world an osario was... Until five seconds before I stepped inside and found this:

An ossuary, of course! A bone depository. A place that confronts you with your own mortality the way nothing else can.

An ossuary, of course! A bone depository. A place that confronts you with your own mortality the way nothing else can. They say the bones here represent burials going back to the tenth century, and that the bones left today represent a mere fraction of what was found at the beginning of the twentieth century. That's when famous scholar Gregorio Marañón took many truckloads full of bones to the Complutense University in Madrid without doing any kind of cataloging. No one knows what happened to those truckloads, they say. It seems odd that Gregorio Marañón would be so careless with precious historical evidence, even in the early twentieth century, but it's a good explanation for why the small canon-vaulted room doesn't overflow.

They say the bones here represent burials going back to the tenth century, and that the bones left today represent a mere fraction of what was found at the beginning of the twentieth century. That's when famous scholar Gregorio Marañón took many truckloads full of bones to the Complutense University in Madrid without doing any kind of cataloging. No one knows what happened to those truckloads, they say. It seems odd that Gregorio Marañón would be so careless with precious historical evidence, even in the early twentieth century, but it's a good explanation for why the small canon-vaulted room doesn't overflow.One visits the ossuary directly after a visit to the old chapter house, which is now the baptistery. New life and death in the space of a minute. Memento mori.

The birds take flight on a cloudy March morning over Wamba. Thanks to the residents of Wamba and the good-humored guide who let us interrupt her day for an unforgettable walk through life, death, and everything in between that fit more than one thousand years into less than two hours.

The birds take flight on a cloudy March morning over Wamba. Thanks to the residents of Wamba and the good-humored guide who let us interrupt her day for an unforgettable walk through life, death, and everything in between that fit more than one thousand years into less than two hours.

Published on June 25, 2018 00:30

May 21, 2018

Royal Entertainment in the Ninth Century: Oviedo's Heyday Monuments

Oviedo seen from Naranco

Oviedo seen from NarancoAll photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss I'm back to blogging after an inexcusable absence. It's time to catch up with all the beautiful things I've been seeing since I got to Spain last September!

It was November, and hadn't rained in Zamora for more than a year. Imagine my surprise when I took the bus only a few hours north to get immediately and thoroughly soaked. And I had a(nother) cold. But, as seen in this previous post, I didn't let those accidents of nature stop me.

After walking one kilometer, huffing and puffing, and being overwhelmed and thrilled with San Julián de los Prados, it was time to sit down in the nearest plaza and call a taxi. I was finally going to a place I'd always thought was in the middle of nowhere. All the photos I'd ever seen and the awe with which the buildings were described suggested they were hard to get to. As it turns out, Naranco Hill, home to two mega-important ninth-century monuments, is not even a suburb of Oviedo, capital city of Asturias. That said, it was probably two kilometers uphill, and in my weakened viral state, it was just as well I took a taxi so I could enjoy it more.

The first unique contribution to Asturian culture sits on the hill, visible from the city, just like any of the other houses on Naranco...

The first unique contribution to Asturian culture sits on the hill, visible from the city, just like any of the other houses on Naranco... ...but it is that rarest of architectural creatures, a medieval building for non-religious use! Even rarer, it's the most beloved example of what the Asturians call pre-Romanesque architecture. Named Santa Maria del Naranco hundreds of years after it was first built, it's survived in great condition!

...but it is that rarest of architectural creatures, a medieval building for non-religious use! Even rarer, it's the most beloved example of what the Asturians call pre-Romanesque architecture. Named Santa Maria del Naranco hundreds of years after it was first built, it's survived in great condition! Ramiro II (mid-ninth century) had this palace built with commanding views of the city below. To go inside, you must be accompanied at all times by a guide who gives an informative tour. The other Naranco monument (see below) is included in the ticket price.

Ramiro II (mid-ninth century) had this palace built with commanding views of the city below. To go inside, you must be accompanied at all times by a guide who gives an informative tour. The other Naranco monument (see below) is included in the ticket price. This is the first building to successfully mount a vaulted ceiling made of stone. Previous vaulted ceilings were always made of wood, a much lighter proposition. But once an architect figures out a technique for stone, even a first creation can last well over one thousand years. Other clever architectural features abound here, and it's little wonder, as this palace was built expressly to host dignitaries and grandees from near and far for policy and diplomatic meetings--and parties. It wasn't a residential palace, but a place dedicated to making an impression.

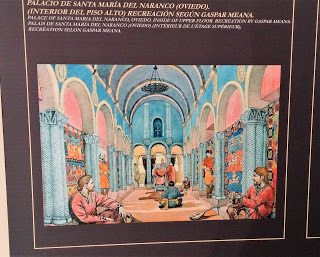

This is the first building to successfully mount a vaulted ceiling made of stone. Previous vaulted ceilings were always made of wood, a much lighter proposition. But once an architect figures out a technique for stone, even a first creation can last well over one thousand years. Other clever architectural features abound here, and it's little wonder, as this palace was built expressly to host dignitaries and grandees from near and far for policy and diplomatic meetings--and parties. It wasn't a residential palace, but a place dedicated to making an impression.  In this artist's rendition of what the palace looked like in Ramiro II's day, we're reminded that the walls were probably painted with bright colors and hung with tapestries, although some dignitaries would still have sat on the floor so as not to sit above the king. Pillows hadn't made it to this part of northern Spain before the ninth century.

In this artist's rendition of what the palace looked like in Ramiro II's day, we're reminded that the walls were probably painted with bright colors and hung with tapestries, although some dignitaries would still have sat on the floor so as not to sit above the king. Pillows hadn't made it to this part of northern Spain before the ninth century.

It has two arcaded porches that are so lovely, I can't understand why this style hasn't been imitated more often.

It has two arcaded porches that are so lovely, I can't understand why this style hasn't been imitated more often. The decorations are subtle, uniform, and surprisingly influenced by the Middle East. I can't help but see the queen's taste reflected here. It was likely the queen's duty to make sure everyone had a good time, and such an important job required sophistication and education as well as instinct.

The decorations are subtle, uniform, and surprisingly influenced by the Middle East. I can't help but see the queen's taste reflected here. It was likely the queen's duty to make sure everyone had a good time, and such an important job required sophistication and education as well as instinct. Here there used to be a balcony from which the king and his guests could contemplate that commanding view.

Here there used to be a balcony from which the king and his guests could contemplate that commanding view. While the top floor was clearly for important meetings and government, the guide presented the bottom floor as more of a mystery. It looks like a crypt, but there are no burials.

While the top floor was clearly for important meetings and government, the guide presented the bottom floor as more of a mystery. It looks like a crypt, but there are no burials.It was probably a cellar. You needed to store a lot of wine to entertain that many dignitaries. The cellar also has a successful vaulted ceiling in stone. Trust me, this is impressive stuff!

A clever architectural trick: See how the arches are longer and narrower at the ends? When you're inside, it creates the illusion of great length.

A clever architectural trick: See how the arches are longer and narrower at the ends? When you're inside, it creates the illusion of great length. Note the fine detailing in every element. Even the columns are carved to look like drapery.

Note the fine detailing in every element. Even the columns are carved to look like drapery.When I have millions of dollars, I'll add some similar details to my writers' retreat castle/palace.

An altar was placed here a few hundred years later, when the palace was consecrated for religious use and given the name Santa Maria.

An altar was placed here a few hundred years later, when the palace was consecrated for religious use and given the name Santa Maria. Is this blast from the past overwhelming your senses and imagination? We're not done yet. Just a bit farther up the hill, close enough for easy access by the king and his guests, we come upon San Miguel de Lillo. Again, photos gave me the impression that this building was in the middle of a field far from the madding crowd. It was a special pleasure to realize it's within easy reach of any able-bodied Oviedo-dweller.

Is this blast from the past overwhelming your senses and imagination? We're not done yet. Just a bit farther up the hill, close enough for easy access by the king and his guests, we come upon San Miguel de Lillo. Again, photos gave me the impression that this building was in the middle of a field far from the madding crowd. It was a special pleasure to realize it's within easy reach of any able-bodied Oviedo-dweller. San Miguel's floor plan is a lot smaller now than when it started out in the middle of the ninth century. It's probably one-third its original size after a collapse in the eleventh century. It gives the impression it's been squished in from the sides, but it's still precious and rare, one of only fifteen examples of Asturian pre-Romanesque architecture that survived the centuries.

San Miguel's floor plan is a lot smaller now than when it started out in the middle of the ninth century. It's probably one-third its original size after a collapse in the eleventh century. It gives the impression it's been squished in from the sides, but it's still precious and rare, one of only fifteen examples of Asturian pre-Romanesque architecture that survived the centuries. They didn't let us take any pictures inside because too many people have been unable to follow the simple request not to use flash. Trust me, it's chock full of column capitals, column bases, and friezes that transport you to the ninth century, if you aren't there already.

They didn't let us take any pictures inside because too many people have been unable to follow the simple request not to use flash. Trust me, it's chock full of column capitals, column bases, and friezes that transport you to the ninth century, if you aren't there already.In the doorway, a frieze depicting circus performers, influenced by Roman wall art via Byzantium, is unique because it's the only non-religious artwork that has been found in a church of this period.

Although not on the scale of San Julián de los Prados, there are some deteriorated paintings here that are the first depictions of the human form in Asturian wall art. They look similar to the people in mozarabic manuscripts and are probably a direct inheritance from Visigothic art.

They carved the jalousie windows out of one single block of sandstone each! A marvel of engineering and sculpture. This is a modern reproduction; the windows shown in the photos above with a plate of glass protecting them are originals.

They carved the jalousie windows out of one single block of sandstone each! A marvel of engineering and sculpture. This is a modern reproduction; the windows shown in the photos above with a plate of glass protecting them are originals. In the Museum of Oviedo, this is a column base from the same era and in much the same style as the column bases in San Miguel de Lillo. I love the exotic look, reflecting the same taste as Santa Maria del Naranco.

In the Museum of Oviedo, this is a column base from the same era and in much the same style as the column bases in San Miguel de Lillo. I love the exotic look, reflecting the same taste as Santa Maria del Naranco. Now that we've returned to the city center, it's a good opportunity to take a look at the last of the four monuments from Oviedo's first heyday. This fountain/well that supplied the city with clean water is the only public civil construction that survives from the ninth century. Although it was outside the city walls at the time, it's now mere steps away from the nightlife/cider district. Here you can see how the ground level has risen over 1100 years.

Now that we've returned to the city center, it's a good opportunity to take a look at the last of the four monuments from Oviedo's first heyday. This fountain/well that supplied the city with clean water is the only public civil construction that survives from the ninth century. Although it was outside the city walls at the time, it's now mere steps away from the nightlife/cider district. Here you can see how the ground level has risen over 1100 years. The engineers built Foncalada to take advantage of a natural spring.

The engineers built Foncalada to take advantage of a natural spring. Carvings include the Asturian cross with a blessing to protect the well: "This sign protects the pious. This sign defeats the enemy." I know I feel safer about Oviedo's water, reading that!

Carvings include the Asturian cross with a blessing to protect the well: "This sign protects the pious. This sign defeats the enemy." I know I feel safer about Oviedo's water, reading that!I saw many more exciting, unique things in Oviedo. It's impossible to exhaust its medieval wonders, and if you like cider, it's absolutely the place for you! But more will have to wait for another post.

My mother has been saving and engineering ways to make money ever since I told her I was going to live in Spain, and very soon, we'll be going on a Grand Tour together. I'll have to take yet another break from the blog, though this one is excusable. See you near the end of June!

Published on May 21, 2018 00:30

April 2, 2018

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Holy Week 2018

Easter Sunday in Zamora

Easter Sunday in ZamoraPhoto 2018 José Pablo Palencia MorchónAll year, I was puzzled as to why Spring Break here in Zamora occurs after Easter. The week before, Holy Week, is so full of activities, I thought, why wouldn't people focus on them rather than going to school? It turns out, they did just that, and now I fully understand: we all need this week of vacation to recover from Holy Week!

It was the best Easter of my life, unlike anything I've ever experienced. I got swept up immediately, after my first procession, to a degree I never would've expected. I didn't think I could love Zamora any more than I already did, but as I learned from my husband, love is infinite. My love for Zamora kept growing with the sense of community, the excitement, the beauty, and the deliciousness.

Below, highlights of a mind-blowing week in pictures (click the F icons to go to the original posts) and videos (click play), and to conclude, a tempting look at some of the special foods of Zamoran Holy Week. As you'll see in the photos and videos, much of it has a strong medieval flair, so even though it happened this week, I'm counting it as a time-travel experience and one of Zamora's medieval treasures.

March 22 - Passion Thursday

March 23 - Friday of Sorrows

The first full, dressed up procession of Holy Week on the Friday of Sorrows takes the Cristo del Espiritu Santo, which is the oldest image to be taken out in procession, from the thirteenth century, and therefore my favorite, from Espiritu Santo to the Cathedral and back again. Scroll to 15:45 to hear the wonderful chorus!

March 24 - Passion Saturday

March 25 - Palm Sunday

March 26 - Holy Monday

Elsewhere in Zamora, possibly the best vocal experience of Holy Week, the Brotherhood of the Christ of the Good Death sings "Jerusalem, Jerusalem" in the Plaza de Santa Lucia on Holy Monday night. Forward to -19:31 to listen.

March 27- Holy Tuesday

Elsewhere on Holy Tuesday: Christ of the Via Crucis and Our Lady of Esperanza meet and say farewell before continuing to their separate churches. Scroll to -11:11 for the big action.

March 28 - Holy Wednesday

March 29 - Holy Thursday

March 30 - Holy Friday

March 31 - Holy Saturday

April 1 - Easter Sunday

How can anyone keep going like this for more than a week? The answer lies at least partly in the food of Holy Week.

These beauties are aceitadas, roughly translated as "oilies." Crisp and toasty, a beautiful balance of sweet and hearty, with the welcome presence of the taste of olive oil, somehow never overwhelming, I had these cookies at school before vacation, at a friend's house while not gawking from the balcony, and finally bought this box at La Tahona del Pan on Amargura Street.

These beauties are aceitadas, roughly translated as "oilies." Crisp and toasty, a beautiful balance of sweet and hearty, with the welcome presence of the taste of olive oil, somehow never overwhelming, I had these cookies at school before vacation, at a friend's house while not gawking from the balcony, and finally bought this box at La Tahona del Pan on Amargura Street. For years, I'd been hearing about torrijas, a special Easter food Spanish people look forward to all year. I looked all over Zamora for a bar or a bakery that could make them for me, but ended up having to use a recipe and make them at home. It's not a service-industry food. Easter Sunday, I had my special bread and the other ingredients, and drum roll please...

For years, I'd been hearing about torrijas, a special Easter food Spanish people look forward to all year. I looked all over Zamora for a bar or a bakery that could make them for me, but ended up having to use a recipe and make them at home. It's not a service-industry food. Easter Sunday, I had my special bread and the other ingredients, and drum roll please... They're pretty much French toast. This bread had cinnamon and lemon juice already. I soaked the slices in milk (probably a way to moisten old, hard Spanish loaves), then bathed them in egg, and fried them up with olive oil, as you do in Spain, and they turned out delightful. Lots of pots and pans to wash for breakfast, though.

They're pretty much French toast. This bread had cinnamon and lemon juice already. I soaked the slices in milk (probably a way to moisten old, hard Spanish loaves), then bathed them in egg, and fried them up with olive oil, as you do in Spain, and they turned out delightful. Lots of pots and pans to wash for breakfast, though. Finally, how does a Brother or Sister of the Congregation of Jesus the Nazarene hold up for six or seven hours of procession on the morning of Holy Friday starting at 5 a.m.? By taking a break at the Avenue of the Three Crosses that includes sopa de ajo (my favorite, wonderfully simple Castilian garlic soup) and something called dos y pingada, which sounds a lot like a cuss word. The dos are two eggs, and the pingada is rustic toasted bread and at least three different kinds of pork, to include ham, loin steak, chorizo, bacon, anything you can think of, depending on which restaurant you end up at. Everyone, even people not in that brotherhood, likes to get in on the dos y pingada action around Easter.

Finally, how does a Brother or Sister of the Congregation of Jesus the Nazarene hold up for six or seven hours of procession on the morning of Holy Friday starting at 5 a.m.? By taking a break at the Avenue of the Three Crosses that includes sopa de ajo (my favorite, wonderfully simple Castilian garlic soup) and something called dos y pingada, which sounds a lot like a cuss word. The dos are two eggs, and the pingada is rustic toasted bread and at least three different kinds of pork, to include ham, loin steak, chorizo, bacon, anything you can think of, depending on which restaurant you end up at. Everyone, even people not in that brotherhood, likes to get in on the dos y pingada action around Easter. Here is the dos y pingada I ended up with at Cafe Brasilia on the Avenue of the Three Crosses: eggs, toast, ham, loin, and morcilla (black pudding). As emotionally drained as I was after watching the final procession on Easter Sunday, after eating this dish, I could've kept going for another week.

Here is the dos y pingada I ended up with at Cafe Brasilia on the Avenue of the Three Crosses: eggs, toast, ham, loin, and morcilla (black pudding). As emotionally drained as I was after watching the final procession on Easter Sunday, after eating this dish, I could've kept going for another week. I will never forget my first Holy Week. Thanks for coming along with me!

Published on April 02, 2018 10:26

March 26, 2018

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Holy Week

The monument to the Merlú (an important Holy Week rite)

The monument to the Merlú (an important Holy Week rite) welcomes visitors to Zamora's Plaza Mayor.

Photo 2017 Jessica Knauss I was raised in the American secular/Protestant tradition, so when Spanish people ask me about Easter, I tell them it's a single day when we bite the ears off chocolate rabbits. (I briefly lament how unimportant Easter has become in Awash in Talent , Part III.) On the other hand, when I ask Zamorans about Easter, they usually launch into thirty minutes to an hour of rapturous memories and excitement for this year's processions, ceremonies, and music with strong recommendations about which events not to miss for any reason.

Zamorans participate in a mock funeral procession for the Burial of the

Zamorans participate in a mock funeral procession for the Burial of the Sardine, Ash Wednesday. Absurdity to kick off Lent.

Photo 2018 Jessica Knauss This is the first time I will be in Spain for all of Semana Santa (Holy Week). (Yes, Easter lasts a lot longer than one day in Spain.) I was laid low by what I hope is my final bad cold of the year during Carnival, though I was able to see the Burial of the Sardine, the final nuttiness before the strict sobriety of Lent.

The Brotherhood of the Holy Burial was

The Brotherhood of the Holy Burial was founded in 1593.

Photo 2017 Jessica Knauss Honestly, Lent in Zamora hasn't seemed that dreary. It's at least partially because everyone's so stinkin' excited about Holy Week! I had to find out more about the origin and meaning of these celebrations! My research included talking to Zamorans, library books that are, for the most part, poems in praise of Holy Week, and a visit to the Holy Week Museum. This is how beloved this "week" is: Holy Week lasts more than one week! It begins on the Thursday before Palm Sunday, known as Passion Thursday, and continues through Easter, and I've even had some inklings that it might go on through the Monday or Tuesday after.

Processional crosses give me a strong medieval vibe.

Processional crosses give me a strong medieval vibe.All photos in the Holy Week Museum 2018 José Pablo Palencia Morchón In the Middle Ages, the Church sought out ways to get the message to the lay population. How could regular people take part in a text-based religion when hardly any of them could read? In northern Europe, Passion Plays and Mystery Plays took hold because the people put themselves in the holy roles. These traditions survived the Protestant Reformation because there are no images involved, only flesh-and-blood people acting as obvious proxies.

Redención by famous float sculptor Mariano Benlliure, 1931

Redención by famous float sculptor Mariano Benlliure, 1931Holy Week Museum In Spain, lay people get involved in reenacting scripture using the images--sculptures and crosses--in their churches. The first evidence we have of Holy Week in Zamora comes from a thirteenth-century text written by Alfonso X's brother indicating that Zamorans had a tradition of "making presentation of Our Lord" on Palm Sunday. What does this mean? It's likely they were already doing what they did yesterday, which was this year's Palm Sunday: carrying a beloved statue of Christ through the streets of Zamora. The first such processions might have been as simple as some of the iconography we see in Alfonso X's Cantigas de Santa María : a church official carrying a small image with few adornments, surrounded by clerics and laity, probably singing and dancing.

Christ of the Lagoon, 16th century

Christ of the Lagoon, 16th centuryHoly Week Museum Enthusiasm spread rapidly, and by the fourteenth century, the first cofradías (brotherhoods) were founded. These societies, first formed according to medieval guild occupations, are associated with a church, or more specifically with one of a church's images. On the appropriate day of Holy Week, according to whether they have a Virgin of Sorrows, a Crucifixion, or any number of other saints or scenes, it's the brotherhood's responsibility to take their image out in procession, normally on an elaborate float. The oldest such float I saw in the Holy Week Museum is from 1522.

Gethsemane with realistic leaves that rustle in the breeze

Gethsemane with realistic leaves that rustle in the breezeHoly Week MuseumDuring the busiest days, several brotherhoods can undertake multiple processions at any and all times of day. Most processions leave from their home churches, but some leave from the Holy Week Museum where the float is on display.

The Last Supper, 20th century

The Last Supper, 20th centuryHoly Week Museum The floats, mobile works of art, can portray any and all Biblical scenes having to do with the Passion, and can have anywhere from a single half-sized statue to a crowded life-sized Crucifixion with thieves, Romans, and Mary Magdalene, to a Last Supper complete with table settings for thirteen. There is usually plenty of room on the sides of the float for candle holders and bouquets of fresh flowers. Some floats have evolved special features such as crucified Christs with articulated arms so that they can be taken from the cross and placed in a tomb. The floats must balance decorative exuberance with the width of the church door and the narrowest street on their processional routes as well as weight distribution.

Underneath the float, neck pads for the float bearers

Underneath the float, neck pads for the float bearersHoly Week Museum Weight distribution is important because the floats are carried on the necks of the brothers (cofrades--women can do it, too, in some brotherhoods). The role of float bearer involves physical strength and sacrifice as well as anonymity because the most spectators will see during the procession are their well-shined shoes.

My WTF face upon discovering that some floats travel on wheels

My WTF face upon discovering that some floats travel on wheelsHoly Week Museum Given what I know about float bearers, and the penitent interpretation I gave them, I was disappointed to find, in the Holy Week Museum, that some floats move along on wheels.

The costume of each brotherhood stands next to its float in

The costume of each brotherhood stands next to its float inthe Holy Week Museum. There are always more brotherhood members outside the float to accompany it along the route. Here we come to the most potentially disturbing sights of Holy Week. While one Zamoran surmised that because the images are often covered in gore, they might frighten children from other countries such as the United States, I think it's the cloaks and headdresses the members wear that are sure to strike the wrong note with an unprepared American.

Costume of the Brotherhood of the True Cross

Costume of the Brotherhood of the True CrossHoly Week Museum The idea behind the brotherhood costumes was that the members are marching in penitence. If people in the street could see who they were, it would be like bragging, literally taking a "holier than thou" attitude. Therefore, many of the brotherhoods use capes to cover recognizable clothing, and a hood that includes a cone to disguise the wearer's height. A certain radical group in the United States understood the advantages of anonymity as they carried out their acts of violence and hatred and appropriated the costume without permission. Holy Week celebrants all over Spain don't have to change their traditional costume because one notorious group in a foreign country uses it for evil. Even knowing all that, some of the costumes are hard to get used to.

This brotherhood's costume is based on shepherds' cloaks.

This brotherhood's costume is based on shepherds' cloaks.Holy Week Museum On the other hand, some brotherhoods use cloaks derived from their original occupations in the Middle Ages and early modern times. They often have intricate embroidery, and anyone could say they're gorgeous.

Holy Week MuseumSome special roles in the procession, such as carrying certain crosses, are so desirable that a brotherhood member must put his name down before he's even taken first communion and might be allowed to fulfill that role when he's in his forties or fifties.

Holy Week MuseumSome special roles in the procession, such as carrying certain crosses, are so desirable that a brotherhood member must put his name down before he's even taken first communion and might be allowed to fulfill that role when he's in his forties or fifties. Holy Week Museum These traditions appear to have survived intact since the thirteenth century. However, Holy Week fell into neglect during the nineteenth century because of a statewide expropriation of Church possessions. It made a spectacular comeback at the end of the nineteenth century because of organizations like Zamora's Pro-Holy Week Society. This society runs the Holy Week Museum and provides all kinds of other support for Zamora's most convivial week of the year.

Holy Week Museum These traditions appear to have survived intact since the thirteenth century. However, Holy Week fell into neglect during the nineteenth century because of a statewide expropriation of Church possessions. It made a spectacular comeback at the end of the nineteenth century because of organizations like Zamora's Pro-Holy Week Society. This society runs the Holy Week Museum and provides all kinds of other support for Zamora's most convivial week of the year. Veronica at the Holy Week Museum King Felipe II (a serious dude who reigned 1556-1598) admonished the Bishop of Zamora against the way Holy Week was being carried out at the time: "There is great disorder in the churches during processions and young people go about with too much ease and disrespect... At the temple doors, in the streets and plazas where most people gather, they spread out delicacies on boards to break the fast... When they come to watch the night processions, some take advantage of the dark to commit dissolute evils, so that these are the days when God is most offended."

Veronica at the Holy Week Museum King Felipe II (a serious dude who reigned 1556-1598) admonished the Bishop of Zamora against the way Holy Week was being carried out at the time: "There is great disorder in the churches during processions and young people go about with too much ease and disrespect... At the temple doors, in the streets and plazas where most people gather, they spread out delicacies on boards to break the fast... When they come to watch the night processions, some take advantage of the dark to commit dissolute evils, so that these are the days when God is most offended." A shop displays its Holy Week wares. Note the folding seat

A shop displays its Holy Week wares. Note the folding seat for when you're waiting hours and hours for a procession to come by.

Photo 2018 Jessica KnaussIn spite of the royal warning, and its modern somber appearance, this spirit of fun has carried through to present day Holy Week. Every Zamoran I spoke with thought of it as a time to get together with friends they've had since forever to eat, drink, sing, and have a lot of fun. My anecdotal evidence indicates that a majority hardly treats it as a religious event at all.

Buy your kiwis and get the scoop

Buy your kiwis and get the scoop on Holy Week happenings.

Photo 2018 Jessica Knauss Hundreds of years ago, the Church was highly successful in getting the lay public involved in Easter. Holy Week turned abstract concepts into tangible acts people could witness with their own eyes and even participate in. One solid sociological theory suggests that community is built through shared ritual. Even if it's lost most of its religious significance, these community bonds are stronger than ever after centuries of wild enthusiasm for these group efforts.

Another shop displays its Holy Week wares.

Another shop displays its Holy Week wares.Photo 2018 Jessica KnaussThe most touching phenomenon I've discovered about Holy Week in Zamora (declared international touristic interest in 1986, UNESCO world immaterial cultural heritage in 2015) again has to do with its many brotherhoods. In other cities, rivalries spring up between brotherhoods and tint the "week" with a competitive (in my mind, negative) streak. In Zamora, no such rivalries exist. Many people are members of multiple brotherhoods. This would be impossible anywhere else, I'm convinced. I'm so proud to be in Zamora for Holy Week. It's sure to be unforgettable.

Recruitment poster for one brotherhood

Recruitment poster for one brotherhoodat a Zamora bus stop

Photo 2018 Jessica Knauss Happy Easter!

Published on March 26, 2018 00:17

March 19, 2018

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Romantic Ruined Castrotorafe

The structures at Castrotorafe were made with red Zamoran bricks.

The structures at Castrotorafe were made with red Zamoran bricks.All photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss Castrotorafe's complex history highlights even further the sense of past glory evoked by contemplating its ruins. It's not just Castrotorafe Castle that's fallen into disrepair. The entire village was declared a ghost town as early as the seventeenth century.

The land had been settled since time immemorial, enjoying special prosperity during Roman times because of its position on the Silver Road between Mérida and Astorga. It's still a stop on one of the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, and when I was there, our tour group spotted two lone pilgrims.

The land had been settled since time immemorial, enjoying special prosperity during Roman times because of its position on the Silver Road between Mérida and Astorga. It's still a stop on one of the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, and when I was there, our tour group spotted two lone pilgrims. The Esla River, which has a history with another impressive monument, sustained human populations here for thousands of years.

The Esla River, which has a history with another impressive monument, sustained human populations here for thousands of years. Much of the town wall survives, giving an impression of a vast fenced-in territory.

Much of the town wall survives, giving an impression of a vast fenced-in territory. In the twelfth century, Castrotorafe entered and fell out of royal favor, with the first documentary evidence granting a town charter. A later expropriation perhaps occurred as punishment after the people of Castrotorafe sided with Portuguese separatists.

In the twelfth century, Castrotorafe entered and fell out of royal favor, with the first documentary evidence granting a town charter. A later expropriation perhaps occurred as punishment after the people of Castrotorafe sided with Portuguese separatists. The current castle was likely built by Don Juan, one of Alfonso X's sons, who declared himself King of León in spite of his brother Sancho's status as King of Castilla y León.

The current castle was likely built by Don Juan, one of Alfonso X's sons, who declared himself King of León in spite of his brother Sancho's status as King of Castilla y León.

The town and its castle belonged at different times to the Order of Santiago and to various nobles, all of whom ended up disappointing their kings.

The town and its castle belonged at different times to the Order of Santiago and to various nobles, all of whom ended up disappointing their kings.

In 1475, the town was taken by forces against Isabel la Católica's rule. By promising Castrotorafe to the Mayor of Zamora, Isabel finally prevailed.

In 1475, the town was taken by forces against Isabel la Católica's rule. By promising Castrotorafe to the Mayor of Zamora, Isabel finally prevailed. Castrotorafe's long history came to an end sometime after the wars of Castilian succession. In 1688, we find the first written notice that the town had been abandoned and was in need of repair.

Castrotorafe's long history came to an end sometime after the wars of Castilian succession. In 1688, we find the first written notice that the town had been abandoned and was in need of repair.

In the nineteenth century, Napoleonic troops bothered to sack the church when they passed through. That's the last time Castrotorafe was sideswiped by history. Various organizations are trying to prevent further deterioration at the site, but in 2010, one of the castle towers fell.

In the nineteenth century, Napoleonic troops bothered to sack the church when they passed through. That's the last time Castrotorafe was sideswiped by history. Various organizations are trying to prevent further deterioration at the site, but in 2010, one of the castle towers fell. The recent drought has created long swaths of dried-out ground cover, and Castrotorafe likely won't be suitable for picnicking without mouthfuls of dust until the rains return. Even more than Castillo de Alba, the ghost town of Castrotorafe evokes a distant past never to return.

The recent drought has created long swaths of dried-out ground cover, and Castrotorafe likely won't be suitable for picnicking without mouthfuls of dust until the rains return. Even more than Castillo de Alba, the ghost town of Castrotorafe evokes a distant past never to return.

Published on March 19, 2018 00:30

March 12, 2018

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Romantic Ruined Castillo de Alba

A corner of Castillo de Alba's homage tower overlooks Ricobayo Reservoir

A corner of Castillo de Alba's homage tower overlooks Ricobayo ReservoirAll photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss I'm pleased to report that I've seen more than ten castles since I arrived in Castilla y León in the middle of September 2017. Yes, there are so many castles here that it's hard to keep count! I've seen beautifully maintained Gothic masterpieces of defensive architecture and lovingly restored bulwarks of several different architectural schools. But the castles that give you the most immediate sense of the passage of time are those that have fallen into ruin.

In this post and the next, I present two ruined castles of Zamora province. Whether they provoke wistful nostalgia for what's gone, a Romantic remembrance of a brave past, or just seem like good places for a picnic, there's no denying that ruined castles present a unique pleasure when you get to climb around on them. In the case of Castillo de Alba, the climbing is literal.

Castillo de Alba is perched on a hill tucked into a valley. To get the full effect, you have to feel a cool breeze on your cheek and hear the shepherd calling gruffly as his sheep move along to the symphonic tones of their bells. I'm not exaggerating. That's what I experienced while taking this picture.

Castillo de Alba is perched on a hill tucked into a valley. To get the full effect, you have to feel a cool breeze on your cheek and hear the shepherd calling gruffly as his sheep move along to the symphonic tones of their bells. I'm not exaggerating. That's what I experienced while taking this picture. Every area of Castilla y León has a signature stone fence style. Looking at this one, there's no mistaking we're in Alba y Aliste.

Every area of Castilla y León has a signature stone fence style. Looking at this one, there's no mistaking we're in Alba y Aliste.

The name Castillo de Alba (Alba Castle) might lead to some confusion, as a village that grew up in the castle's shadow is also called Castillo de Alba. The fertile hills and valleys of this area have been occupied by humans since pre-Roman times, and the current castle of Castillo de Alba was first constructed in the twelfth century as an important defense on the border with Portugal on the site of a Neolithic fort. In the thirteenth century, Alfonso IX of León granted the castle to the Knights Templar, and they held it until the crown took it back to grant it to a noble dynasty. Finally, Enrique IV of Castile and León created the County of Alba y Aliste and declared the castle its seat in 1489.

The name Castillo de Alba (Alba Castle) might lead to some confusion, as a village that grew up in the castle's shadow is also called Castillo de Alba. The fertile hills and valleys of this area have been occupied by humans since pre-Roman times, and the current castle of Castillo de Alba was first constructed in the twelfth century as an important defense on the border with Portugal on the site of a Neolithic fort. In the thirteenth century, Alfonso IX of León granted the castle to the Knights Templar, and they held it until the crown took it back to grant it to a noble dynasty. Finally, Enrique IV of Castile and León created the County of Alba y Aliste and declared the castle its seat in 1489. The town of Castillo de Alba seen from the castle

The town of Castillo de Alba seen from the castle

You approach the castle via a steep and picturesque mountain trail.

You approach the castle via a steep and picturesque mountain trail. At the top of the trail, you're confronted with the largest surviving chunk of the castle, which used to be one of the towers. Its imposing robustness gives the sense that the people who constructed this castle wanted you to stay away!

At the top of the trail, you're confronted with the largest surviving chunk of the castle, which used to be one of the towers. Its imposing robustness gives the sense that the people who constructed this castle wanted you to stay away!

Looking closer, you see the modern caretakers want you to stay away, too! And with good reason. Rocks are falling off the castle structure at random moments and the approach is steep and inhospitable, such that if you aren't an experienced climber, you might get stuck on top of the castle and have to be rescued.

Looking closer, you see the modern caretakers want you to stay away, too! And with good reason. Rocks are falling off the castle structure at random moments and the approach is steep and inhospitable, such that if you aren't an experienced climber, you might get stuck on top of the castle and have to be rescued. Luckily, I was with a Castilian who is apparently part mountain goat, and I made it to the top of the castle and back down again to show you these photos.

Luckily, I was with a Castilian who is apparently part mountain goat, and I made it to the top of the castle and back down again to show you these photos. Inside the most intact tower, it's a Romantic tangle of overgrown nature.

Inside the most intact tower, it's a Romantic tangle of overgrown nature.

The castle has an irregular floor plan that adapts to the hillside that protects it so well.

The castle has an irregular floor plan that adapts to the hillside that protects it so well. A lot of the outer walls remain. It's sometimes not easy to distinguish what is construction and what is natural rock formation.

A lot of the outer walls remain. It's sometimes not easy to distinguish what is construction and what is natural rock formation. This sliver of corner is all that remains of the homage tower.

This sliver of corner is all that remains of the homage tower.

The castle became neglected when the border with Portugal stabilized and noble and royal interests focused elsewhere. Rest assured, Romantic warriors! It was never defeated or destroyed by humans.

The castle became neglected when the border with Portugal stabilized and noble and royal interests focused elsewhere. Rest assured, Romantic warriors! It was never defeated or destroyed by humans.Next week, not just a castle, but an entire ghost town!

Published on March 12, 2018 00:30

March 5, 2018

Zamora's Medieval Treasures: Espíritu Santo

Espíritu Santo on its unobstructed side

Espíritu Santo on its unobstructed sideAll photos in this post 2018 Jessica Knauss Some of Zamora's medieval treasures are so humbly self-effacing that they don't even have visiting hours. One such place is the Iglesia del Espíritu Santo, which was consecrated on the pleasing date of June 12, 1212, by the bishops of Zamora and Coria, with a third from somewhere in Portugal. Ten years later, Alfonso IX of León confirmed its importance by declaring it and the nearby hospital royal property with his full protection.

In spite of these auspicious beginnings, it seems today Espíritu Santo is visited only by parishioners and those in the know about the Romanesque scene in Zamora. I attended mass one recent Sunday in spite of my lack of Catholicism, and I'm glad I did.

One of the smaller Romanesque gems in this city, Espíritu Santo gives a first impression of being boxed in by more modern constructions. The only facade not blocked to view is the southern one. Even the eastern side, with its lovely Romanesque rose window, makes you work for the privilege of a closer look.

One of the smaller Romanesque gems in this city, Espíritu Santo gives a first impression of being boxed in by more modern constructions. The only facade not blocked to view is the southern one. Even the eastern side, with its lovely Romanesque rose window, makes you work for the privilege of a closer look. It's crowded in under the bell gable, too. Don't even think about going around the back. There's no way to get there. I've read that the church has a nice back garden space with archaeological findings on display, but only at certain times of year.

It's crowded in under the bell gable, too. Don't even think about going around the back. There's no way to get there. I've read that the church has a nice back garden space with archaeological findings on display, but only at certain times of year. Utilitarian corbels Like a few other churches in Zamora, most notably the cathedral, Espíritu Santo is influenced by the austere Cistercian school of architecture. While its exterior is agreeable with its warm Zamoran stone, the only flourishes are the rose window and two curlicue-shaped acroteria flanking the lowest part of the building, which you learn when you walk in is the apse. Even the corbels are utilitarian.

Utilitarian corbels Like a few other churches in Zamora, most notably the cathedral, Espíritu Santo is influenced by the austere Cistercian school of architecture. While its exterior is agreeable with its warm Zamoran stone, the only flourishes are the rose window and two curlicue-shaped acroteria flanking the lowest part of the building, which you learn when you walk in is the apse. Even the corbels are utilitarian. The double arch entrance could hardly be simpler.

The double arch entrance could hardly be simpler.

You don't expect the quiet yet colorful delights awaiting inside. To begin with, the elegant apse evokes heavens above, drawing the eye upward with a subtle point after the smooth semicircle of the double archway. The small windows above had stained glass installed in 1963 that gives a Gothic feel without making a secret of their "mid-century modern" origin. The wooden ceiling is a restored version of what was installed in the fifteenth century.

You don't expect the quiet yet colorful delights awaiting inside. To begin with, the elegant apse evokes heavens above, drawing the eye upward with a subtle point after the smooth semicircle of the double archway. The small windows above had stained glass installed in 1963 that gives a Gothic feel without making a secret of their "mid-century modern" origin. The wooden ceiling is a restored version of what was installed in the fifteenth century. We can also see 1963 stained glass appropriately depicting a dove--symbol of the Holy Spirit (Espíritu Santo)--from this interior perspective on the rose window.

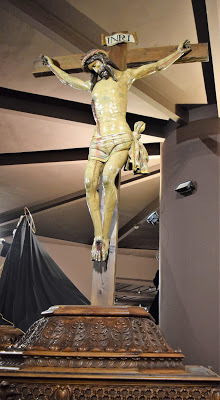

We can also see 1963 stained glass appropriately depicting a dove--symbol of the Holy Spirit (Espíritu Santo)--from this interior perspective on the rose window. The main altar is home to an attractive thirteenth-century crucifix that was discovered in bad shape during the 1963 renovations. Known as Cristo del Espíritu Santo, it's been lovingly restored and is now taken out in procession during Easter festivities. (Easter or Holy Week is a huge deal in Zamora. More on that in a later post.) Its early Gothic curves are evocative without being gory, and the long modesty panel recalls its Romanesque predecessors while commanding a more realistic sense of fabric drapery.

The main altar is home to an attractive thirteenth-century crucifix that was discovered in bad shape during the 1963 renovations. Known as Cristo del Espíritu Santo, it's been lovingly restored and is now taken out in procession during Easter festivities. (Easter or Holy Week is a huge deal in Zamora. More on that in a later post.) Its early Gothic curves are evocative without being gory, and the long modesty panel recalls its Romanesque predecessors while commanding a more realistic sense of fabric drapery. What's this behind the Cristo? It's something else wonderful discovered in 1963, a swath of stone painted in the late thirteenth century. (This is my favorite period of medieval painting because it encompasses the

Cantigas de Santa Maria

.) A cross is flanked by blurred forms we can still distinguish as angels.

What's this behind the Cristo? It's something else wonderful discovered in 1963, a swath of stone painted in the late thirteenth century. (This is my favorite period of medieval painting because it encompasses the

Cantigas de Santa Maria

.) A cross is flanked by blurred forms we can still distinguish as angels. On the other side of the church, on the northern wall, awaits a trio of unexpected curiosities. On the left, you can see an image of St. Isidore the Farmer created in the eighteenth century that goes on procession through the streets of Zamora on May 15 every year.

On the other side of the church, on the northern wall, awaits a trio of unexpected curiosities. On the left, you can see an image of St. Isidore the Farmer created in the eighteenth century that goes on procession through the streets of Zamora on May 15 every year. The second of the recovered thirteenth-century paintings shows a cross surrounded by geometric forms.

The second of the recovered thirteenth-century paintings shows a cross surrounded by geometric forms. Although the inscription is all but illegible, this recumbent abbot is identified as Franco de Ribera, who died in 1350. I haven't found out exactly why the statue so unusually lies on its side, sticking out of the wall. It must've once occupied a niche in another location, where it could assume the normal posture.

Although the inscription is all but illegible, this recumbent abbot is identified as Franco de Ribera, who died in 1350. I haven't found out exactly why the statue so unusually lies on its side, sticking out of the wall. It must've once occupied a niche in another location, where it could assume the normal posture. The southern wall, opposite the apse, displays the last of the recovered thirteenth-century paintings: the Tetramorphos, or the four apostles who wrote the Gospels, arranged around another cross.

The southern wall, opposite the apse, displays the last of the recovered thirteenth-century paintings: the Tetramorphos, or the four apostles who wrote the Gospels, arranged around another cross. This Baroque Pentecost used to occupy the center of a large altarpiece. Small, boxed in by the unyielding tide of time, but unexpectedly feisty in the way it reveals its own historical personality, Espíritu Santo was well worth sitting (and standing) through a cheerful Lenten mass with guitar and voice accompaniment throughout. It is only one of more than twenty Romanesque temples in my dear Zamora, and just the third one I've presented on this blog. As hard as it may be to believe, the best is yet to come!

This Baroque Pentecost used to occupy the center of a large altarpiece. Small, boxed in by the unyielding tide of time, but unexpectedly feisty in the way it reveals its own historical personality, Espíritu Santo was well worth sitting (and standing) through a cheerful Lenten mass with guitar and voice accompaniment throughout. It is only one of more than twenty Romanesque temples in my dear Zamora, and just the third one I've presented on this blog. As hard as it may be to believe, the best is yet to come! Assuming my role as author, I have the delight of letting you know that

Awash in Talent

's publishers are running a great promotion: now until March 11, it's only 99 cents in Kindle format. Since it's regularly $3.99, it's 75% off! You can't beat the price for hours of zany entertainment that just might make you think.

Assuming my role as author, I have the delight of letting you know that

Awash in Talent

's publishers are running a great promotion: now until March 11, it's only 99 cents in Kindle format. Since it's regularly $3.99, it's 75% off! You can't beat the price for hours of zany entertainment that just might make you think. I have not yet earned out my advance on Awash in Talent--readers haven't yet purchased enough copies for me to start making money beyond what the publishers awarded me way back in in mid-2016--so by taking advantage of this promotion, for only 99 cents, you can help me reach that goal. If I could start earning royalty money on my beloved paranormal urban fantasy novel, it would help both my confidence as an author and my bank account hugely. I appreciate your support very much!

I have not yet earned out my advance on Awash in Talent--readers haven't yet purchased enough copies for me to start making money beyond what the publishers awarded me way back in in mid-2016--so by taking advantage of this promotion, for only 99 cents, you can help me reach that goal. If I could start earning royalty money on my beloved paranormal urban fantasy novel, it would help both my confidence as an author and my bank account hugely. I appreciate your support very much!That's Awash in Talent , only 99 cents now until March 11, 2018.

Published on March 05, 2018 00:30

February 26, 2018

Segovia's Medieval Treasures: Frescoes and Dusk in Maderuelo

Santa María and the new bridge at Maderuelo, Segovia

Santa María and the new bridge at Maderuelo, SegoviaAll photos in this post 2017 Jessica Knauss Maderuelo has been around since time immemorial, but got its final start in the tenth century under a "repopulation" order from Fernán González, the first Count of Castile and the father of Count García in my Seven Noble Knights .

The day I visited Maderuelo with our knowledgeable and entertaining guide, David, I was suffering with the first full day of a common cold, i.e., the day when you think it's not really common and you might just be dying, so I was unable to appreciate the fact that this is a site my characters could recognize! This is one of the things I love about Spain: you can't avoid stumbling onto some piece of interesting history, anywhere you go.

Maderuelo's city limits are defined by the rocky outcrop on which it sits, commanding views over the majestic plains of the province of Segovia.

You enter via Entrance to the Village Street...

You enter via Entrance to the Village Street... ... and if you make it past the town guardians...

... and if you make it past the town guardians... ... you go through a ruggedly lovely door in the Romanesque town wall.

... you go through a ruggedly lovely door in the Romanesque town wall. You turn around to find buildings just as ancient leaning together to make you feel as if you were one of the inhabitants during the town's heyday.

You turn around to find buildings just as ancient leaning together to make you feel as if you were one of the inhabitants during the town's heyday. Turning back around, you're confronted immediately with San Miguel, which has seen better days. Although it's been restored and is currently in use as a church, most of its Romanesque aspects are deteriorated or were austere to begin with.

Turning back around, you're confronted immediately with San Miguel, which has seen better days. Although it's been restored and is currently in use as a church, most of its Romanesque aspects are deteriorated or were austere to begin with. San Miguel's plain chapel has a delightful

San Miguel's plain chapel has a delightful late Romanesque Virgin and Child.

David points out the contrast between what most restorations

David points out the contrast between what most restorations look like and what they ought to look like. Our guide, David, took the opportunity to explain his views on restoring medieval buildings. A lot of times, he said, restorers leave the stone exposed so people can feel like that's what it looked like way back when. But, David said, of course they didn't leave the stones exposed, indoors or out. They wanted smooth surfaces for painting or otherwise decorating indoors and to give a finished look and protect the stones outdoors. The buildings lasted this long because of the protective layers of stucco or other materials that impeded weather getting into the mortar and cracking the stones into rubble. David's central question in Maderuelo was why don't they restore that most lovely and useful part? It would be even more beautiful for visitors to gaze upon and would prevent further weatherization.

Baroque facade of Santa María

Baroque facade of Santa María

The Church of Santa María, farther inside the town, has the most Romanesque traces within the wall. It's a fascinating combination of building materials, put together with a utilitarian chaos that makes its history hard to interpret. It has a lovely, understated Romanesque portal with geometric motifs.

The Church of Santa María, farther inside the town, has the most Romanesque traces within the wall. It's a fascinating combination of building materials, put together with a utilitarian chaos that makes its history hard to interpret. It has a lovely, understated Romanesque portal with geometric motifs. Mysterious archways in Santa María

Mysterious archways in Santa María

David tries to illuminate the chaos into order with his green laser pointer. However, we spent the most time puzzling over some blind arches on the opposite side of the building. The use of the arches is unknown. Made of red brick, they immediately suggest mudéjar craftsmanship, and the horseshoe shape of the arches indicates this may be the earliest part of the building. Did Romanesque architects take over a mosque for use as a church? We may never be certain. I strongly felt that if I hadn't been suffering with that cold, I could've come up with a plausible answer no one else had brought up before. Maybe the cold medicine was giving me delusions of grandeur.