Loren C. Steffy's Blog, page 17

July 18, 2013

`Dell and Back:’ My Texas Monthly debut

Not all investors are happy with Michael Dell’s buyout offer.

A few weeks ago, the editors at Texas Monthly asked me to write a piece about the buyout battle being waged for Dell Inc. I covered Dell in the 1990s and early 2000s, and I jumped at the chance. The shareholder vote on the buyout was supposed to take place Thursday morning, but it was delayed.

So the magazine decided to post my article on its web site, along with a short update from me at the top. (If you prefer to read it in print, the next issue should be on shelves soon.)

The delay of the vote isn’t a good sign for Michael Dell’s plan to take his company private, although I still believe he’s likely to prevail. I’ll be doing another update for the TM website next week when the vote is supposed to be concluded.

June 26, 2013

Writing on platforms old and new

Things have been a little quiet on this blog for the past week or so, in part because I’m getting a handle on juggling different writing assignments on many different platforms. In case you missed it, I recently started blogging about energy issues at Forbes.com.

A post last week on the resentencing of fallen Enron chief Jeff Skilling prompted my former Bloomberg colleague Chris Roush to ask me for a related post for his Talking Biz News site.

And I’m wrapping up a magazine piece that should be out in a few weeks. More on that later. All of this, of course, comes as a backdrop to my new day job as a senior writer with 30 Point Strategies.

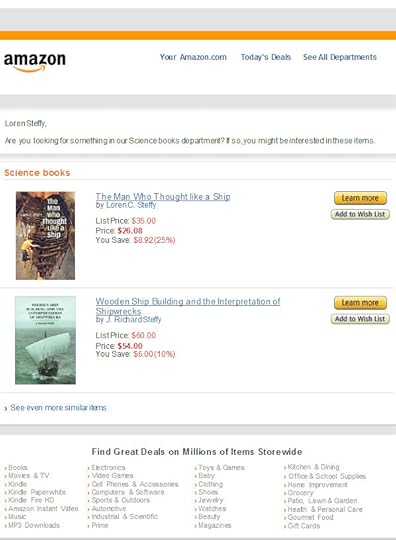

As busy as my schedule has been, I did have to pause to enjoy this email from my friends at Amazon.com. I guess their marketing algorithms really do understand what we readers like….

June 15, 2013

Father’s Day

My father and me, testing a Cub Scout rubber-band rocket in about 1975.

Publisher’s Weekly just put out its list of the “10 Worst Dads in Books,” which seems like bad timing just before Father’s Day. While the article notes that “bad dads turn up less in fiction than bad moms,” the issue of bad fathers in books reminded me of some early discussions I had with publishers about The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

I contacted a few commercial publishers, but they seemed disappointed that I hadn’t suffered any childhood angst, that my father hadn’t left me scarred somehow by showing greater love for his ships than his children.

Fortunately, the folks at Texas A&M Press knew my father well, and they understood. I approached my book as a journalist, but also as a son writing about his father. The fact that he was an inspiration was, I decided, part of the narrative. Soon after my father’s obituary appeared in the New York Times, a friend from Oregon emailed me and said “he sounds like the father the rest of us always wished we had.” I suppose that’s true.

A few months before he died, my father asked me out of the blue if I ever resented the fact the he was gone so much when I was growing up. I was shocked. We’d never talked about it, but even though he was often overseas for months at a time, I never felt abandoned. What I remembered was the hours he spent helping me on projects, taking me places, encouraging my interests and intellectual curiosity.

“I can’t think of anything that mattered to me that you were there for,” I told him.

He looked surprised. “I missed your high school graduation,” he said. “Your mother never let me forget it.”

I thought about it for a moment and realized he was right. He’d gotten delayed overseas that year and hadn’t made it home in time. But I stood by my statement, and I still do.

After my father’s death in 2007, my brother and I knew lots of people would focus on his amazing accomplishments in nautical archaeology. In writing our eulogies, we wanted to focus on him as a father. Later, I tried to capture that in the book, too. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

Several years ago, after an INA board meeting, one of Dad’s students approached me and said she wanted to tell me how much Dad meant to his students and what a profound impact he’d had on their lives.

I remember thinking “yeah, he does that.” After all, if anyone can testify to the profound impact that Dad had on their lives, I can.

As many of you know, we spent a year on Cyprus when I was a kid – I was about seven at the time. That experience in and of itself was life changing – not many kids have a Crusader castle for a playground. But it was that time on Cyprus that awakened my interest in writing.

There weren’t a lot of books in English readily available for kids my age, and I was still young enough to command a bedtime story.

Often, the power would go off about the time I was getting ready for bed, and so between the lack of literature and the lack of lights, Dad began telling me stories from history. I learned about the Battle of Thermopolyae, the conquest of Alexander the Great, and, of course, Richard the Lionheart and the Third Crusade in our darkened living room.

But one night, Dad sat down at story time with some typewritten pages in his hand and began to read them to me. It was the tale of a pine tree – an Aleppo pine – that grew in a zig zag fashion. Because of this deformity, the other trees in the forest laughed at him. They were made into furniture and fine woodworking, but this tree, this Crooked Aleppo, was left behind.

One day a shipwright showed up in the forest and decided that the crooked tree would be perfect for the keel of a ship – a merchant ship as it were. The ship and its keel, crooked no more, sailed the Mediterranean for many years until one day it sank. Many more years went by until strange men with tanks on their backs uncovered the keel. They tried to raise him, and he broke into 16 pieces. They rebuilt him in a Crusader castle in a small town in northern Cyprus.

I think I caught on at the first mention of the word “keel,” but it didn’t matter. I was captivated. Every writer has some story, something they read in their youth, that they can point to as the spark that ignited their passion for words. For me, it was the story of Crooked Aleppo.

Not only was it a great story, but it was a story about something I knew and, more importantly, written by someone I knew. And written for me. It made me realize that stories didn’t just appear on shelves or in magazines, people wrote them. They wrote them for others. And I could write them too.

The summer we returned from Cyprus, I shamelessly copied my Dad’s format. I wrote an entire series about every piece of the Kyrenia ship – the frames, the maststep, the mast.

And from then on, I was always writing, always weaving stories.

It almost backfired, though. Years later, when I was a senior in high school, still driven by my passion for writing, I was dragging my feet about college. [Kids, you may now plug your ears.]

One night my dad came into my room and said we needed to talk seriously about college. I basically said I was thinking I’d just become a great and famous writer instead.

My dad, of course, didn’t get angry, didn’t raise his voice or even show any signs of disapproval. He paused for a moment, and then calmly said that he understood how I felt, but that I should realize making a living as a writer could be difficult and that it was a subjective business. And then he said: “I think you’re a good writer. But I’m your father, and I’m a little biased. So we have to realize there’s a chance you could stink. And if you stink, you’ll want something to fall back on.”

Even at 17, I couldn’t argue with that logic. Needless to say, I enrolled in A&M, found a career that combined my passion for words with the thirst for knowledge I inherited from my father and have spent the past 20 or so years trying very hard not to stink.

All of you who knew my dad as a friend, colleague, professor, mentor, brother, uncle or grandfather, were fortunate. But Dave and I were uniquely blessed because we knew him as a father.

At the time, it all seemed very normal, but I was reminded of how special it was just a few days ago when a friend in Oregon, having seen the stories on Dad’s death, said: “He sounds like the father the rest of us always wished we had.”

I’ve been a father myself now for about 16 ½ years, and every day I try to live up to the example he set. Every day, I come up short. His are shoes too big to fill.

Fortunately, my father also taught me perseverance, determination and that important achievements come through persistence.

Dad showed us the importance of chasing dreams. In fact, his life could be a practical guide to chasing dreams. He took risks, he gambled, but his gambles were rooted in practical sensibility and his victories were muted with humility.

As he allowed us to share in this great adventure that was his life, he never forgot the importance of simple pleasures like bedtime stories.

And in pursuing his own dream, he managed to ignite the dreams of others.

Maybe there are a lot of bad dads in books. I’m grateful to tell the story of a good one. Happy Father’s Day.

June 10, 2013

The debut of Nautical Discoveries

Interested in knowing more about what’s going on in nautical archaeology? Since writing The Man Who Thought Like a Ship, I’ve found that information on the web is sparse and scattered. I’ve compiled a magazine on Flipboard, Nautical Discoveries, which collects information from around the web, mixed with some of my own posts from this blog.

Interested in knowing more about what’s going on in nautical archaeology? Since writing The Man Who Thought Like a Ship, I’ve found that information on the web is sparse and scattered. I’ve compiled a magazine on Flipboard, Nautical Discoveries, which collects information from around the web, mixed with some of my own posts from this blog.

If you’re a Flipboard user, simply search on the term “nautical discoveries” in the login page. Or you can paste this link: http://flip.it/6ZzNa. Flipboard is free, although it’s only available as a mobile app.

Let me know what you think, and if you have any ideas for content or ways to improve Nautical Discoveries, please let me know.

June 3, 2013

What’s on your summer reading list?

I’ve never compiled a true summer reading list. I always have a backlog of books and magazine articles I’m trying to get through, and no matter how much reading I get done, there’s always more, regardless of the season. I do try to polish off at least one substantial book during vacation, however. This year, I think my vacation book will be Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. I’ve already downloaded it to my iPad and taken a peek at the introduction.

I’ve never compiled a true summer reading list. I always have a backlog of books and magazine articles I’m trying to get through, and no matter how much reading I get done, there’s always more, regardless of the season. I do try to polish off at least one substantial book during vacation, however. This year, I think my vacation book will be Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. I’ve already downloaded it to my iPad and taken a peek at the introduction.

Also on the list for this summer: The Man Who Tried to Save the World by Scott Anderson. It’s the story of Texas-born relief worker Fred Cuny, who disappeared in Chechnya in 1995. The book was recommended to me by a colleague after the Boston Marathon bombings for its explanation of political divides in the region.

If you’ve read The Man Who Thought Like a Ship, (yes, that’s a shameless plug for my own book), you know that I spent some time as a child playing in a Crusader castle in Cyprus. That sparked a lifelong fascination with the Crusades, and I typically read at least one book a year related to them. I have three awaiting my attention: Thomas Beckett: Warrior, Priest, Rebel by John Guy; Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for the Apocalypse by Jay Rubenstein; and Eleanor of Acquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England by Ralph V. Turner. I’m not sure which one I’ll pick yet, although I’m leaning toward the Beckett book.

I also have a couple of unfinished reads that I hope to wrap up this summer. The first is Plastic Ocean: How a Sea Captain’s Chance Discovery Launched a Determined Quest to Save the Oceans. Written by Charles Moore and Cassandra Phillips, it’s the story of a sailor returning from Hawaii who stumbles upon an “oceanic desert” that has become the world’s largest garbage dump. He’s determined to find out why so much discarded plastic and garbage has collected there and what can be done about it. This book was recommended to me by a conservationist in the Houston area, and I read half of it on a plane last fall but never finished it.

The second “partial” that I hope to finish by the end of summer is the latest installment in Robert Caro’s Lyndon Johnson biography, The Passage to Power. I’ve read the previous three volumes, and I’ve learned that I enjoy Caro’s work best when I read it in segments, more like a serial than a single book. I’ve been picking away at this one for a while, and with any luck, I’ll be done with it by September.

Finally, I’ll need a few novels to mix in with the nonfiction. I had hoped to be enthralled with T.C. Boyle’s San Miguel, but it was surprisingly less engaging than his previous works. Boyle is one of my favorite novelists, so I may go back and read one of his earlier works, such as Water Music or World’s End.

After reading an excerpt from Philipp Meyer’s The Son in the latest issue of Texas Monthly, I’ve added that to my list as well.

Of course, I probably won’t make it through all these in the next three months, but the last thing I’d want is to have a list that too short and find myself in mid-August with nothing to read.

What ‘s on your reading list for the summer?

May 28, 2013

The Sinking of the Bounty

I spent much of the Memorial Day weekend catching up on periodicals, and one in particular is worth noting. Matthew Shaer’s piece for the Atavist on The Sinking on the Bounty is both a griping read and a great example of how an electronic format can enhance long-form narratives. Interspersed with the text are weather maps tracing the path of Hurricane Sandy and video of some of the Bounty’s crew being rescued by the Coast Guard.

I spent much of the Memorial Day weekend catching up on periodicals, and one in particular is worth noting. Matthew Shaer’s piece for the Atavist on The Sinking on the Bounty is both a griping read and a great example of how an electronic format can enhance long-form narratives. Interspersed with the text are weather maps tracing the path of Hurricane Sandy and video of some of the Bounty’s crew being rescued by the Coast Guard.

Fortunately, it’s rare for a tall sailing ship to sink in a storm these days, but as I read Shaer’s account, I found myself thinking how many other ships, many of which are now being excavating and studied by archaeologists, must have gone down in the much the same way.

A strong sense of place

Denver’s Cub Scout pack, in about 1974, marching in the annual parade to celebrate the town’s founding. I’m two rows behind the U.S. flag bearer.

As a writer, one of the things I’m drawn to is a narrative with a strong sense of place. I recently returned to my hometown of Denver, Pa., to give a talk and do a book signing for my father’s high school alumni banquet. Denver had about 1,500 people when we lived there, and while it’s a little bigger now, it remains much as I remember it as a child.

It still has one stoplight, and Main Street doesn’t look all that different than it did when my grandparents ran an electrical store there.

In fact, Denver’s strong sense of place actually made it a character in my book, The Man Who Thought Like a Ship. When I talk about the book, I often introduce the town by noting that I went to elementary school in the same building that my father did. Behind that building is a cemetery in which you can find the graves of my great- and great great-grandparents.

That continuity, that stability, was fundamental to my father’s story. Much of who he was stems from the town, and Denver itself is a character in the book.

For that matter, much of who I am stems from my early childhood there. As if to drive home the point, the night after the alumni dinner, I got together with some friends I knew in elementary school. Many of my classmates still live in the area. Like me, much of who my father was is rooted in Denver’s unique persona.

As I note in the book, Denver also played a special role in the history of nautical archaeology. Though it’s a good 120 miles from tidewater, it was briefly the worldwide headquarters for nautical archaeology. My father was born there and grew up there, of course, but in 1975, George Bass and his family returned to the United States with plans to found what would become the Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

Unsure where to go, the Basses moved to Denver so George and my father would be better able to plan their next move. Eventually, of course, they affiliated their fledgling institute with Texas A&M University, but for about about nine months, tiny, land-locked Denver was the center of all the activity.

The Gift of Curiosity

My father, J. Richard Steffy, in the third grade in 1931.

I recently returned to my hometown of Denver, Pennsylvania, to speak to graduates of my father’s high school. The school closed in the 1950s, and because some of the graduating classes were so small – my father’s class had nine students – they do one combined reunion every year.

During dinner, the discussion at our table turned to Helen Crouse, who had been my father’s third-grade teacher. In The Man Who Thought Like a Ship, I write that my father credited her with encouraging his interest in ships.

He was still building model boats out of paper and homemade paste then, yet she fed his interest by tracking down books on ships and seafaring even though Denver and the surrounding towns didn’t have a library at the time. When I told this story at the dinner table, everyone smiled and nodded their heads.

Mrs. Crouse, it seems, didn’t just serve as an inspiration to my father, but to most of her students. After my talk, one member of the audience asked for a show of hands from others who had been inspired by her. Half the hands in the room went up.

As the husband of a third-grade teacher, I found myself wondering how Mrs. Crouse would fare in today’s era of standardized testing and one-size-fits all education. She understood that unlocking a child’s intellectual curiosity is the key to a lifetime of learning. That’s not a skill that can be measured with a test, it’s a gift. In my father’s case, it was the gift that enabled him to chase his dreams and to learn, ultimately, to think like a ship.

Book signing in Bermuda

A view of Hamilton harbor

The latest issue of the INA Quarterly (see page 5), the official publication of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, has pictures from a book signing I did at the institute’s board of directors meeting in Bermuda. The three-day event included lectures, updates on INA’s field projects and a fascinating tour of the National Museum of Bermuda.

INA asked me to attend the event and give a talk on The Man Who Thought Like a Ship. Many in attendance knew my father, of course, but they didn’t know the full story of how he came to rebuild ancient ships.

It was a chance for me to see some good friends and relive some fond memories. And did I mention it was in Bermuda?