Edward Feser's Blog, page 73

August 23, 2016

Is Islamophilia binding Catholic doctrine?

Catholic writer Robert Spencer’s vigorous criticisms of Islam have recently earned him the ire of a cleric who has accused him of heterodoxy. Nothing surprising about that, or at least it wouldn’t be surprising if a Muslim cleric were accusing Spencer of contradicting Muslim doctrine. Turns out, though, that it is a Catholic priest accusing Spencer of contradicting Catholicdoctrine.

Catholic writer Robert Spencer’s vigorous criticisms of Islam have recently earned him the ire of a cleric who has accused him of heterodoxy. Nothing surprising about that, or at least it wouldn’t be surprising if a Muslim cleric were accusing Spencer of contradicting Muslim doctrine. Turns out, though, that it is a Catholic priest accusing Spencer of contradicting Catholicdoctrine. Cue the Twilight Zone music. Book that ticket to Bizarro world while you’re at it.The priest in question is Msgr. Stuart Swetland, a theologian and president of Donnelly College. The occasion was a radio exchange about Islam between Spencer and Swetland and a print follow-up, the details of which are recounted at Spencer’s website. Swetland, it is important to note, is not a theological liberal and is known for his loyalty to the magisterium of the Church. In the interests of full disclosure I might also add that I have met Msgr. Swetland and found him to be a decent and pleasant fellow.

All the same, his remarks are in my opinion deeply confused, unjust to Spencer, and even damaging to the Church. And that is putting it charitably.

In a statement that reads a little like a disciplinary notice from the CDF (and which is reproduced by Spencer at the link above), Swetland cites a number of positive remarks about Islam to be found in Vatican II’s Nostra Aetate and in the statements of several recent popes. These include remarks by Pope Francis to the effect that “authentic Islam and the proper reading of the Koran are opposed to every form of violence.” Arguing that faithful Catholics ought to agree with such remarks, Swetland writes:

[W]e owe to their teaching a “religious submission of mind and will” …

Robert Spencer’s positions seem to be at odds with the magisterial teachings on what authentic Islam is and what Catholic are called to do about it (accept immigrants, avoid hateful generalizations, show esteem and respect, etc.) At least in the area of morals, Robert seems to be a dissenter from the papal magisterium…

It is very important for all believers that the authentic teaching of the Church be clear so that we may know the truth and attempt to live it to the full. I submit that there is a serious difference between the repeated magisterial teachings of the Church and the teaching of Robert Spencer in this area. (emphasis added)

End quote. Now, Msgr. Swetland is certainly correct to urge a fair-minded and dispassionate evaluation of Islam. I myself have argued (hereand here), contra some hotheaded critics of Islam, that it is simply not plausible to deny that Muslims and Christians refer to the same deity when they use the word “God,” or to allege that Muslims worship some pagan tribal deity. At the same time, it is naïve and dishonest to insist a priori that a fair-minded and dispassionate evaluation of Islam simply must result in the conclusion that on any “authentic” interpretation, Islam is peaceful and compatible with the modern Western political order. Indeed, I have also argued (hereand here) that there are serious reasons to doubt such a conclusion.

Msgr. Swetland is certainly also correct to emphasize, as he does in his statement, that the assent Catholics owe the teachings of the popes and the Church extends beyond merely those that are proposed infallibly. He is right to reject the erroneous minimalist view that holds that as long as a teaching is not proposed infallibly, Catholics are free to dissent from it. However, there is also an opposite extreme error of a maximalist sort, according to which Catholics are bound to assent to virtually anything a pope says that is even remotely connected with matters of faith and morals. That is simply not the case. As I noted in a recent post on papal fallibility and infallibility, there are five basic categories of magisterial statement, and it is only the first three which require assent from Catholics. Hence it is no good merely to pull a remark out from some papal speech or even from a magisterial document of higher authority, and then declare peremptorily that all Catholics are obliged to assent to it. One must carefully determine to which of the five categories of magisterial statement the remark belongs. This is especially true where the remark seems to put forward some novel view, where there are contingent historical circumstances or empirical claims involved, and so forth.

It is bad enough when political pundits and other theological amateurs engage in the intellectually sloppy procedure in question. But a professional theologian like Msgr. Swetland should know better. And in my judgment, his comments on Spencer exhibit exactly this failing. Other critics of Swetland have pointed out various specific problems with his argument. For example, William Kilpatrick has pointed out that Pope Benedict XVI himself acknowledged that Nostra Aetate’s remarks on non-Catholic religions are problematic. Fr. John Zuhlsdorf notes that Nostra Aetate was in any case intended to have merely pastoral rather than doctrinal import.

But the deeper problem is that Swetland’s suggestion that there is or could be such a thing as “magisterial teaching on what authentic Islam is” is, not to put too fine a point on it, as preposterous as the suggestion that there is or could be magisterial teaching on what authentic jazz is, or magisterial teaching on what the authentic interpretation of Heidegger is. It simply badly gets wrong the range of the competence the Church’s magisterium claims for itself (as Swetland critic John Zmirak has pointed out).

This should be obvious from Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium, which Swetland himself cites in his own defense but a crucial detail of which he ignores. The document says that Catholics are obliged to assent, specifically, to teaching concerning “matters of faith and morals” (emphasis added). The Code of Canon Law, which Swetland also quotes, makes exactly the same qualification.

Now, “matters of faith” concern the body of Catholic theological doctrine inherited from scripture and tradition and interpreted by councils and popes. This includes teachings concerning the Trinity, the nature of Christ, original sin, nature and grace, justification, the sacraments, and so forth. It also includes historical claims very closely connected with these theological teachings, such as claims about the Resurrection of Christ, Peter’s status as the first pope, and so on. Matters of “morals” concern the body of Catholic ethical teaching inherited from scripture and tradition and interpreted by councils and popes. It also includes matters of natural law, of which the Church claims to be an authoritative interpreter.

Questions about the nature of Islam and the content of its doctrines simply do not fall into either one of these categories. Islam is not only a religion distinct from Catholicism, but arose six centuries after what Catholicism regards as the close of public revelation at the time of the apostles. In no way, then, from the point of view of Catholicism, can Islam represent a genuine revelation from God. Hence determining what counts as “authentic Islam” is in no way a part of the Church’s task of handing on or interpreting the deposit of faith. How Islam arose, what it teaches, its political and cultural implications, etc. are empirical questions on a par with questions such as what the causes of World War II were, whether Lao Tzu really existed, what the chemical composition of salt is, what the basic tenets of Georgist economic theory are, and so forth. Since they lie outside the domain of Catholic faith and morals, the Church has no special expertise on such matters and thus cannot pronounce authoritatively on them.

What a pope or ecclesiastical document has to say about Islam thus seems obviously to fall into what, in the post linked to above, I labeled category 5 statements, i.e. statements of a prudential sort on matters about which there may be a legitimate diversity of opinion among Catholics. A Catholic ought seriously and respectfully to consider statements of this category which concern Islam, but is under no obligation to assent to them. Hence, questions such as whether Islam is inherently more prone to generate terrorism than other religions are, whether Islam is compatible with liberal democracy, how many Muslim immigrants ought to be allowed into a country and under what circumstances, etc. are in the nature of the case questions about which good Catholics can legitimately disagree. Even the question of whether Christians and Muslims refer to the same thing when they use the word “God” -- and I certainly believe that they do -- cannot be a matter of orthodoxy. There is nothing contrary to binding Catholic doctrine in claiming that Muslims worship some pagan tribal deity, even if (I would argue) this claim is false, ungrounded, and too often driven by emotion rather than clear thinking.

(A critic might say: “But hasn’t the Church pronounced on all sorts of non-Catholic doctrines, such as socialism and communism, various heresies, etc.? So why can’t she pronounce on what counts as authentic Islam?” But such an objection rests on confusion. When (for example) Pope Leo XIII condemned what socialists say about private property, he wasn’t saying “Every Catholic is obligated to believe that one of the tenets of socialism is the rejection the institution of private property.” Rather, he was saying “Every Catholic must accept the institution of private property.” His point was not authoritatively to define what counts as authentic socialism but rather authoritatively to condemn certain errors which happen to have been widely associated with socialism and which are at odds with Catholic teaching. If it somehow turned out that socialists don’t really reject private property after all, that wouldn’t affect Leo’s teaching, because the point of his teaching was to tell Catholics that they ought to uphold private property, not to give a lesson in political science about the history and tenets of socialism.)

So, while it is perfectly legitimate for Msgr. Swetland to disagree with Spencer’s analysis of Islam, it seems to me manifestly unjust, and indeed outrageous, for him to label Spencer a “dissenter” -- as if Spencer ought to be lumped in with the likes of Hans Küng and Catholics for Choice!

But it is worse than that. When a prominent orthodox Catholic theologian and churchman like Msgr. Swetland confidently (but falsely) asserts that taking a positive view of Islam and rejecting opinions like Spencer’s are nothing less than matters of binding Catholic doctrine, he threatens to give grave scandal. For some Catholics who sincerely think that Spencer’s views are well-supported might mistakenly conclude that the Church requires the faithful to accept falsehoods, and may for that reason even consider leaving the Church. And some non-Catholics otherwise attracted to Catholicism might refrain from entering the Church, on the mistaken supposition that doing so would require them to assent to something they sincerely believe to be false. (Judging from the YouTube combox discussion the radio debate between Spencer and Swetland has generated, some people are drawing exactly these sorts of conclusions.)

I have no doubt that Msgr. Swetland is sincere and only means well. But in my opinion he owes Spencer a retraction and apology.

Published on August 23, 2016 09:17

August 17, 2016

Adventures in the Old Atheism, Part II: Sartre

Having surveyed the wreckage of modern Western civilization from the lofty vantage point of Nietzsche’s Superman, let’s now descend to the lowest depths of existential angst with Jean-Paul Sartre. So pour some whiskey, put on a jazz LP, and light the cigarette of the hipster girl dressed in black reading Camus at the barstool next to you. Let’s get Absurd.Our theme in this series is how starkly the gravitas of many “Old Atheist” writers contrasts with the glib banality of the New Atheism. Consider the ritual appeal to Hume in critiquing First Cause arguments for the existence of God. There are insuperable problems with Humean views about causality, as I have argued in many places (e.g. here). But put that aside for now. The New Atheist forgets all about such views almost as soon as he has deployed them. They amount to little more than a debating tactic or talking point, intended merely to stymie an opponent and block an unwelcome conclusion. The New Atheist has no interest in thinking through their wider implications or ultimate defensibility. But suppose someone seriously believed with Hume that causes and effects are all “loose and separate,” so that any effect or none might with equal likelihood follow upon any cause, and so that a thing or event might, as likely as not, pop into existence with no cause or explanation whatsoever?

Having surveyed the wreckage of modern Western civilization from the lofty vantage point of Nietzsche’s Superman, let’s now descend to the lowest depths of existential angst with Jean-Paul Sartre. So pour some whiskey, put on a jazz LP, and light the cigarette of the hipster girl dressed in black reading Camus at the barstool next to you. Let’s get Absurd.Our theme in this series is how starkly the gravitas of many “Old Atheist” writers contrasts with the glib banality of the New Atheism. Consider the ritual appeal to Hume in critiquing First Cause arguments for the existence of God. There are insuperable problems with Humean views about causality, as I have argued in many places (e.g. here). But put that aside for now. The New Atheist forgets all about such views almost as soon as he has deployed them. They amount to little more than a debating tactic or talking point, intended merely to stymie an opponent and block an unwelcome conclusion. The New Atheist has no interest in thinking through their wider implications or ultimate defensibility. But suppose someone seriously believed with Hume that causes and effects are all “loose and separate,” so that any effect or none might with equal likelihood follow upon any cause, and so that a thing or event might, as likely as not, pop into existence with no cause or explanation whatsoever?Sartre imagines just this in his novel Nausea , and nausea is what he thinks such a person would experience, as surely as if he’d been riding an especially violent rollercoaster. For reality is on the Humean empiricist view something of a rollercoaster, with unpredictable turns and drops awaiting us, in principle, at every moment. Sartre has his protagonist say:

I went to the window and glanced out… I murmured: Anything can happen, anything…

Frightened, I looked at these unstable beings which, in an hour, in a minute, were perhaps going to crumble: yes, I was there, living in the midst of these books full of knowledge describing the immutable forms of the animal species, explaining that the right quantity of energy is kept integral in the universe; I was there, standing in front of a window whose panes had a definite refraction index. But what feeble barriers! I suppose it is out of laziness that the world is the same day after day. Today it seemed to want to change. And then, anything, anything could happen…

Sometimes, my heart pounding, I made a sudden right-about-turn: what was happening behind my back? Maybe it would start behind me and when I would turn around, suddenly, it would be too late… I looked at them as much as I could, pavements, houses, gaslights; my eyes went rapidly from one to the other, to catch them unawares, stop them in the midst of their metamorphosis… Doors of houses frightened me especially. I was afraid they would open of themselves. (pp. 77-78)

(Bas van Fraassen quotes some of these lines in his essay “The world of empiricism,” to give a sense of the flavor the world must have on a consistent empiricism.)

But it is not in the external, material world that Sartre locates the most disorienting aspect of atheism. That is to be found instead in the inner world of the conscious, acting subject. In Being and Nothingness , Sartre famously draws a distinction between being-in-itself and being-for-itself. By being-in-itself Sartre has in mind a mere thing or object, a physical phenomenon as it exists objectively or independently of human consciousness. Being-in-itself exhibits “facticity” insofar as it is simply given or fixed. As opposed to what? As opposed to being-for-itself, which is the human agent, conceived of as consciousness projecting forward toward an unrealized possibility. Being-for-itself exhibits “transcendence” insofar as it is not fixed or given in the way that a mere thing or object is, but is rather dynamic and constantly making itself. It might therefore be said to amount, in a sense, to a kind of “nothingness” rather than a being.

Well, what does all that mean? And what does it have to do with atheism? Let’s slow down a bit and work through Sartre’s position carefully. The first thing to note is that action is for Sartre always intentional or directed towards an end, and seeks to remedy some objective lack, something missing, some non-being. For example, you order French fries because you want them but don’t have them. Your action aims or is directed at the state of affairs of eating French fries, a state of affairs which, before the action takes place, does not exist. Now, for this reason, Sartre thinks that no factual state can suffice to generate an action, since an action is always projected toward something non-existent. Again, before you carry out the action of ordering the fries, the state of affairs of your eating French fries does not exist, is not among the facts that make up the world. And yet that non-existent state of affairs is in some sense the cause of your action.

Defenders of free will are in Sartre’s view therefore mistaken in trying to uphold their position by looking for examples of actions without a cause, since acts are intentional or directed toward an end, and this non-existent end is itself a kind of cause. But by the same token, Sartre thinks that critics of the idea of free will are wrong to deny its existence on the grounds that our actions are caused, because these critics have too narrow a conception of cause. They look for all causes in the realm of factual states, and ignore the crucial role of non-existent states of affairs like that of your eating the French fries. In effect, they fallaciously try to reduce being-for-itself (which cannot be understood except in terms of directedness toward what is as yet non-existent) to being-in-itself (which is entirely intelligible in terms of existent facts). Yet even the attempt at such a reduction itself undermines the reduction, since before one undertakes the action of interpreting being-for-itselfas a kind of being-in-itself, that interpretation does not itself yet exist and thus is not within the realm of the factual or the in-itself.

What Sartre is doing here, I would suggest, is noting (in a somewhat idiosyncratic, obscure, and potentially misleading jargon) that action is irreducibly teleological or intelligible only in terms of the notion of final cause -- of which the intentionality or directedness of thought is a specific instance -- whereas those who deny free will typically want to analyze human action in exclusively efficient-causal, non-teleological, and non-intentional terms. And the very attempt to eliminate teleology or intentionality from the story is self-defeating, since such an attempt qua action will itself aim at a certain outcome (and thus exhibit teleology) and will involve representing the world in a certain way (and thus involve intentionality). Sartre, I would suggest, is essentially calling attention to the incoherence problem that is fatal to eliminative materialism and related doctrines.

But Sartre’s preferred mode of expression is much more melodramatic (and unfortunately, much less precise). For example, he famously speaks of the “nothingness [which] lies coiled at the heart of being -- like a worm,” and which is the source of our freedom (Being and Nothingness, p. 56). The idea is that we cannot avoid acting, but in acting are always projecting ourselves toward some end or outcome that does not yet exist and precisely for that reason cannot fix or determine what we do. Even the attempt to interpret ourselves as cogs in a deterministic machine is itself an opting for but one possible interpretation among others, and thus is not forced upon us. No sooner has one entertained that interpretation than it dawns upon him that he could in the very next moment instead reject it and adopt another. It is as if we are, in acting, always trying vainly to plug a black hole which simply sucks up anything we throw into it and perpetually remains as open as it ever was. This is precisely what our freedom consists in: the absence of anything in the realm of facticity, of being-in-itself, of the objective world beyond consciousness, which can possibly fix, determine, or settle how one shall act.

As the harrowing talk of “nothingness” being “coiled… like a worm” implies, this freedom is not for Sartre a cause for relief or celebration. Nor is his insistence on the reality of free will (contra Sam Harris and other New Atheists) a wish-fulfilling attempt to salvage some shred of human specialness in the face of atheism and the advance of science. On the contrary, Sartre regards the denial of free will as itselfan instance of “bad faith” or intellectual dishonesty. For the denial of free will is simply incoherent, while the exercise of free will is -- when one truly understands what it entails -- frightening, and something we have an obvious motive for wanting to avoid. There is absolutely nothing for which one is not ultimately in some sense responsible, in Sartre’s view. If I say that my actions are all the result of heredity, bad upbringing, stress, or what have you, then it is nevertheless the case that I have opted for this interpretation, could have chosen another instead, and might yet choose another in the next moment. It is in this sense that Sartre famously holds that one even chooses one’s own birth and the events that took place before one’s birth. For one always opts for some interpretation of exactly how one’s birth and those other events led to one’s current circumstances, and could choose some alternative interpretation instead. That is to say, what significance to give one’s birth and the other events that were outside one’s control is always up to one. One is never able finally to say: “This is just the way these things have affected who I am and what I do, and that’s out of my hands.”

Given how deep our responsibility goes, and how vertiginous it is relentlessly to be faced with the need to choose, there is constant temptation to try to find some escape by locating something beyond consciousness that is the “true” source of one’s actions -- deterministic laws of physics, genes, familial and other social influences, the movement of history, or what have you. But there is no escape, and the free-will-denying atheist is for Sartre no less engaged in self-deception than the religious fundamentalist. Moreover, unlike the religious believer or the traditional metaphysician, the modern atheist has nothing to look to for guidance in how to choose -- no God, no Platonic realm of Forms, no Aristotelian natures of things.

This is the force of Sartre’s famous slogan “existence precedes essence.” For the theist and the traditional metaphysician, what a human being is is metaphysically prior to the fact that any particular human being exists. There is a fact of the matter about what it is to be human, a nature or essence -- being a rational animal, say, or being made in God’s image -- that is independent of any actual human being’s existence and choices, and what is good or bad for a human being is to be defined in terms of these pre-existing facts about his nature. But if one rejects all such theistic and metaphysical assumptions, and also follows out the implications of Sartre’s analysis of free will, then there is a sense in which this order of things is reversed. That is to say, a human being’s existence is prior to his essence -- he must choose what he is to be, and this choice is never fixed once and for all but must be revisited constantly. Nor, given the lack of any metaphysical grounding for such choices, do any of them have any ultimate rationale or justification. An air of absurdity inevitably surrounds the human condition. To look at the world this way just is to be a Sartrean existentialist.

So, no Richard Dawkins-style happy talk for Sartre about enjoying one’s life in the absence of God. “I am condemnedto be free,” Sartre famously writes (p. 567, emphasis added), indeed “abandoned” to a harsh reality in which responsibility cannot be evaded (p. 569) -- cannot be passed on either to God or to the naturalistic forces the atheist would put in place of God. “I am without excuse,” Sartre says, “for from the instant of my upsurge into being, I carry the weight of the world by myself alone without anything or any person being able to lighten it” (p. 710). For Sartre, it is not the delusional optimism of the Atheist Bus Campaign but the ennui of the existentialist hero that is the mark of true authenticity.

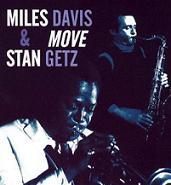

Though, famously, this ennui had for him its compensations. Sartre’s Old Atheism is world-weariness, whiskey, a smoky bar, and a beautiful French woman lighting your cigarette while Miles Davis plays in the background. The New Atheism, meanwhile, is goofy bus advertisements, pimply combox trolls live-blogging a Reason Rally, and Richard Carrier making a crude pass at you. Why the hell would anyone ever want to be a NewAtheist?

Published on August 17, 2016 11:32

August 13, 2016

Review of Harris on Hume

Just back from a very enjoyable week at the Thomistic seminar in Princeton. Regular blogging will resume shortly.

Just back from a very enjoyable week at the Thomistic seminar in Princeton. Regular blogging will resume shortly. In the meantime, my review of Hume: An Intellectual Biography by James A. Harris appears in the Summer 2016 issue of the Claremont Review of Books .

Published on August 13, 2016 19:06

August 3, 2016

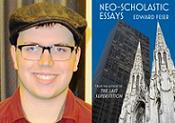

Shinkel on Neo-Scholastic Essays

At The University Bookman, Ryan Shinkel reviews my book

Neo-Scholastic Essays

. Titling his review “Last Scholastic Standing,” Shinkel writes:

At The University Bookman, Ryan Shinkel reviews my book

Neo-Scholastic Essays

. Titling his review “Last Scholastic Standing,” Shinkel writes: Early modern philosophers such as René Descartes and Francis Bacon rejected… the teleology of the Scholastics…

Against this degeneration stands the Thomist philosopher Edward Feser… He has taken a route in metaphysics (the study of ultimate causes) similar to that of MacIntyre in moral philosophy…

[Feser’s] method… works well in a wide range of areas including cosmological arguments for the existence of God, the hard problem of consciousness, and property rights… [The book is] recommended [as an] introduction to Feser’s larger [body of] work… [and] would particularly benefit graduate philosophy students who aspire to the older framework of Aristotle and Aquinas.

End quote. Shinkel also raises an objection to what I have to say in the book about questions of ethics. Appealing to the Aristotelian distinction between theoretical and practical reasoning, Shinkel notes that while an Aristotelian approach to ethics does indeed make use of theoretical knowledge about human nature, it also holds that practical reasoning is of a different kind than theoretical reasoning. Hence (to use Shinkel’s example), while theoretical reasoning might ask “What is justice?”, practical reasoning asks “What is the just action for this situation?” Accordingly, Shinkel says, “theoretical reasoning is necessary but not sufficient: insights from human experience also prove necessary.” However, he also suggests, “[Feser] suppos[es that] Thomist metaphysics are exclusively sufficient” for ethics, so that I do not (he thinks) provide an adequate account of the Aristotelian approach to ethics.

But Shinkel has here confused a difference in emphasiswith a difference in principle. It is true that in the articles in the book that are concerned with moral questions (about property rights and sexual morality, for example) I have a lot to say about general principles and about the relevant theoretical considerations concerning human nature, but less to say about how contingent circumstances determine how to apply the general principles to particular cases. But that is only because (a) these are essays rather than book-length treatments of their subject matters, and (b) it is the general principles and background metaphysical considerations about human nature that are the most widely misunderstood today, and thus in most immediate need of discussion and defense. I nowhere claim to be answering every question that might arise about these subjects, and I certainly never say (and never would say) that every such question can be answered by way of a priori deduction from general theoretical principles.

All the same, Shinkel raises an important issue, and I thank him for his kind review. (Earlier reviews of Neo-Scholastic Essays are discussed hereand here.)

Published on August 03, 2016 11:58

July 28, 2016

Liberalism and the five natural inclinations

By “liberalism” I don’t mean merely what goes under that label in the context of contemporary U.S. politics. I mean the long political tradition, tracing back to Hobbes and Locke, from which modern liberalism grew. By natural inclinations, I don’t mean tendencies that that are merely deep-seated or habitual. I mean tendencies that are “natural” in the specific sense operative in classical natural law theory. And by natural inclinations, I don’t mean tendencies that human beings are always conscious of or wish to pursue. I mean the way that a faculty can of its nature “aim at” or be “directed toward” some end or goal whether or not an individual realizes it or wants to pursue that end -- teleology or final causality in the Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) sense.Aquinas famously identifies what he takes to be the basic human inclinations in Summa Theologiae I-II.94.2. Commentators often summarize these in a list of five items. For example, the Dominican moral theologian Servais Pinckaers lists them as follows:

By “liberalism” I don’t mean merely what goes under that label in the context of contemporary U.S. politics. I mean the long political tradition, tracing back to Hobbes and Locke, from which modern liberalism grew. By natural inclinations, I don’t mean tendencies that that are merely deep-seated or habitual. I mean tendencies that are “natural” in the specific sense operative in classical natural law theory. And by natural inclinations, I don’t mean tendencies that human beings are always conscious of or wish to pursue. I mean the way that a faculty can of its nature “aim at” or be “directed toward” some end or goal whether or not an individual realizes it or wants to pursue that end -- teleology or final causality in the Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) sense.Aquinas famously identifies what he takes to be the basic human inclinations in Summa Theologiae I-II.94.2. Commentators often summarize these in a list of five items. For example, the Dominican moral theologian Servais Pinckaers lists them as follows:1. The inclination to the good

2. The inclination to self-preservation

3. The inclination to sexual union and the rearing of offspring

4. The inclination to knowledge of the truth

5. The inclination to live in society

(See Pinckaers’s books Morality: The Catholic View , at pp. 97-109, and The Sources of Christian Ethics , chapter 17, for his detailed treatment of each of these.)

Some comments on each: Our inclination to the good is the most fundamental of the inclinations. It is what Aquinas is talking about in his famous first principle of natural law, viz. that good is to be pursued and evil avoided. The idea is that in acting we always pursue what we taketo be good in some way or other. Aquinas doesn’t mean that everyone always chooses to do what he thinks is morallygood, or that everyone believes that there is such a thing as an objective standard of moral goodness in the first place. He is well aware that people sometimes do what they know to be morally wrong, that there are people who reject the very idea of morality, etc. His point is that even these people still regard the object of their action as good in the thin sense that it provides some benefit, would be worthwhile to pursue at least in some respects, etc. Given this very rudimentary inclination to the good together with complete rationality and knowledge of what is in fact good, we would do what is morally right. But of course, these latter conditions often do not hold. (See my paper “Being, the Good, and the Guise of the Good” in Neo-Scholastic Essays for detailed discussion and defense of Aquinas’s first principle.)

Pinckaers emphasizes that there is a special connection between this basic inclination and love, since to love something is, for the A-T tradition, to will the good of that something. The less perfect is one’s orientation toward what is in fact good, the more deficient will be his love, as I noted in a recent post.

The inclination to self-preservation is obvious enough, though some may think that the existence of suicidal people is counterevidence. It is not, and Aquinas is of course well aware that there are such people. A suicidal person is not someone who lacks this inclination, but rather someone who intentionally frustrates it. (And even then, not perfectly. Even a suicidal person will initially tend to duck if you fire a gun at him, will struggle if you try to drown him, etc. He has to work to overcome these spontaneous tendencies.) As always, we must keep in mind that by “inclinations” Aquinas does not primarily have in mind the conscious desires we happen to have, but rather the deeper level of natural teleology or final causality which exists below the level of consciousness. To be sure, our conscious desires generally track that deeper level; we usually do consciously want to preserve ourselves. But as with everything else in the world of changeable, material things, imperfections and disorders are bound to occur, and our conscious desires sometimes come apart from the natural teleology of our various faculties.

That is certainly true of the third natural inclination, toward sexual intercourse and the child-rearing that is its natural sequel. In general, people want to have sexual intercourse with someone of the opposite sex, and also want to have children. But of course, there are exceptions -- people with homosexual desires, people who lack any interest in sex, people who don’t want children, and so on. That is not counterevidence to Aquinas’s claim, because, again, he isn’t in the first place making a claim about what people all consciously desire, but rather a claim about the natural ends of our faculties. As with suicidal people, conscious desires in this case too can come apart from natural teleology. (See my essay “In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument,” also in Neo-Scholastic Essays, for detailed exposition and defense of the A-T account of the natural ends of our sexual faculties. See also some relevant earlier blog posts.)

Similar remarks can be made about the natural inclination toward knowledge of the truth. Here, though, it seems to me that it is even more difficult for natural teleology and conscious desire to come apart. It might seem otherwise given that there are people who claim not to believe in objective truth, people who engage in even overt self-deception, and so forth. But even cognitive relativists and other anti-realists about truth think that it really is the case that there is no such thing as objective truth and that those who suppose otherwise are mistaken. (This is why such views at the end of the day simply cannot be coherently formulated.) And someone who wants to avoid knowing certain truths, who won’t let himself dwell on uncomfortable evidence, etc. thinks that it really is the case that it would in some way be bad to know those truths or dwell on that evidence. In these ways, our inclination toward truth is operative even in the very act of trying to frustrate it.

Aquinas makes special note of knowledge of the truth about God as being among the ends of this fourth of our natural inclinations. The idea is that as rational animals we are naturally oriented toward finding the explanations of things. God qua First Cause, knowable by way of philosophical arguments, is the ultimate explanation of things, and thus knowledge of God and his nature is the ultimate fulfillment of our intellectual powers.

The fifth inclination is what Aristotle and Aquinas have in mind when they say that man is a social and political animal. We are oriented by nature to organize into families, extended families, villages, and the like, and to set up institutions with the authority to govern these social organizations. And for the A-T natural law tradition, this political authority derives not from any social contract but from the natural law itself, which preexists any contract. Moreover, our social nature is not reducible to the herd behavior of non-rational animals, but participates in our rationality. It is manifest in language, culture, religion, science, and the other social activities and institutions that other animals lack because they lack intellects. The good we realize by virtue of being social animals is also a common good in the sense that it is not reducible to the sum of private goods of the individuals who make up society. The good of one’s country (say) is not just the aggregate of the private good of this particular citizen, the private good of that particular citizen, etc. Being an organic part of the larger social whole is itself a good over and above the private goods each individual could enjoy on his own.

The ordering of the five inclinations is not accidental. At least in a rough way, the list moves from inclinations we share with many things to inclinations more specific to us. The first inclination, toward the good, is one shared in a sense by all things. For goodness or badness, on the A-T analysis, is defined in terms of how well or badly a thing manifests its nature, and everything manifests its nature to some extent (otherwise it wouldn’t be the kind of thing it is in the first place) and is in that sense and to that extent good. The second inclination, toward self-preservation, is found in living things specifically, and thus also in man as one living thing among others. The third, toward sex and child-rearing, is even more specific, limited to certain kinds of animals. The fourth, toward truth, is (among animals, as opposed to angels, who are incorporeal) limited to us as rational animals, where rational animality is our essence. The fifth, toward sociality of the higher, rational sort we exhibit involves a property or proper accident that flows from our essence as rational animals (in the A-T sense of the word “property”).

Because they are natural to us, these five inclinations cannot be extinguished. They are always present in human beings and always manifest themselves in some way and to some extent. However, and as has already been indicated, their manifestation can be frustrated and distorted in various ways. Intellectual error can lead us to deny one or more of them, and moral vice can make us reluctant to affirm or consistently to pursue one or more of them. Historical and cultural circumstances can also obscure our view of them and distort their manifestation.

This brings us to liberalism -- again, in the broad sense of the tradition extending back to Hobbes and Locke and represented today by positions as diverse as the egalitarian liberalism of Rawls, the classical liberalism or libertarianism of Nozick, and so forth. The characteristic thesis of liberalism is that society and government are not natural to us, but artificial. They arise out of a contract or agreement of some sort (what sort depending on what version of liberalism we’re talking about), between individuals who do not have any preexisting obligations to one another or to any larger social whole. Indeed, there is no social whole of which the individuals are naturally a part, and thus no common good. There are only the private goods of the individuals, and if they decide to form some larger whole it is only for the sake of facilitating those private goods. Moreover, for the liberal, unless the individuals in some way consent to there being a political authority (via a Lockean social contract, bargaining in Rawls’s original position, an initial group of clients signing on with a Nozickian dominant protective agency, or what have you) then there simply cannot be such an authority, and the individuals have no obligation whatsoever to recognize any purported authority.

In short, liberalism essentially rejects the fifth of the basic natural inclinations and is therefore to that extent fundamentally at odds with the A-T natural law tradition.

To forestall misunderstandings, note that I am not here talking about questions such as whether it can be legitimate to resist or overthrow an unjust government, whether popular elections are the least bad way to determine who holds office, etc. An A-T natural law theorist certainly could answer (and many A-T theorists in fact have answered) such questions in the affirmative. But those are essentially questions about which specific persons get to exercise political authority, who gets to hold office and how to determine that, etc. What is at issue here is the more fundamental question of whether the consent of the individuals is the ultimate foundation of there being any such thing as political authority, any such thing as offices of government, in the first place. The liberal tradition says Yes, the A-T natural law tradition says No. Again, for the A-T tradition, society is natural to us rather than artificial and political authority (as a general, background condition of the existence of society, as distinct from some particular concrete form that that authority might take) derives from natural law rather than consent.

Nor is its rejection of the idea that man is a social animal (as A-T understands that claim) the only characteristic feature of liberalism. The other characteristic feature is its insistence not only on the distinctionbetween church and state (which Christianity has always affirmed) but on a sharp separation in principle between church and state, so that the state can in no way favor or be influenced by the doctrine of any particular religious body. (Traditional Christian doctrine holds that such a rigid separation cannot be absolutely required as a matter of principle, even if it is sometimes necessary or advisable in practice.) In Locke, this separation did not rule out a generic philosophical theism as something the state ought to favor, but the subsequent liberal tradition has tended to exclude even this. (I discussed the nature of the traditional Christian view of the relation between Church and state and how liberalism departed from it in some detail in an earlier post.)

Associated in the liberal tradition with this exclusion of religion from politics has been a tendency toward skepticism about the possibility of genuine knowledge where theological matters are concerned. For if we really could have such knowledge, it would seem unreasonable for government not to take account of it in setting policy, any more than it would be reasonable for government to ignore scientific knowledge. Locke’s contemporary Jonas Proast noted the skeptical implications of Locke’s doctrine of religious toleration. A more thoroughgoing and emphatic skepticism about the possibility of religious knowledge has become ever more deeply ingrained in the liberal tradition in the centuries since, to the point where contemporary liberals tend to think it self-evident that religion as such is a matter of “faith” understood as an irrational commitment, which for that reason ought to have no influence whatsoever on public policy. (I discuss Locke’s position and Proast’s criticisms of it in chapter 5 of my book Locke .)

Now, as I’ve noted, Aquinas held that knowledge of God was the ultimate fulfillment of our natural inclination toward knowledge of the truth. To the extent that liberalism presupposes skepticism about the possibility of theological knowledge -- and indeed tends to promote such skepticism as a way of making sure that religion will be kept out of politics -- it is incompatible with the fourth of our natural inclinations.

There is another respect in which liberalism is at least in tension with this fourth inclination. Hobbes had an extremely “thin” conception of the moral law. In Hobbes’s state of nature, everyone is at liberty to do whatever he likes, not only legally but morally. It is the chaos that this inevitably generates that leads individuals in the state of nature to give up their absolute liberty and form civil society. The tendency of Hobbesian contractarian thinking about morality, though, is in a decidedly libertine and minimalist direction. If the individual does not consent to some restriction on his liberty of action -- not just a legal restriction, but even a moral restriction -- then he cannot be bound by such a restriction. Locke’s conception of morality is much “thicker,” even if not nearly as thick as the A-T conception. In Locke’s state of nature, we are not at liberty to do whatever we like. Even if we are not yet obliged to submit to any government, we are still obliged even in the state of nature to submit to a moral law that is in no way the product of human convention or contract and is knowable by reason apart from special divine revelation. Hence, though Locke would not permit any but the most generic religious belief to influence government policy, there is nothing in Lockeanism per se that rules out letting various moralconsiderations influence government policy. For example, there is nothing in Lockeanism per se that would prevent the outlawing of abortion.

However, the liberal tradition has tended over the centuries to follow Hobbes rather than Locke on this particular matter (even if it has of course preferred Locke’s limited state to Hobbes’s absolutist state). That is to say, just as the liberal tradition has over the centuries tended toward increasing skepticism about the possibility of theological knowledge, it has also tended toward increasing skepticism about the possibility of moral knowledge of anything more than a very ”thin” or minimalist “live and let live” sort. That is why it has tended increasingly to insist that matters of “personal morality” (e.g. concerning abortion, homosexuality, etc.) not be allowed to influence public policy. It is why Rawls will not only not permit any sort of religious doctrine to influence the basic structure of society, but will not permit any other “comprehensive doctrine” (of even a secular moral or philosophical sort) to do so.

As in the case of religion, the skepticism and the attitude toward public policy go hand in hand. If it were admitted that we really could have genuine knowledge where “personal morality” is concerned, then it would be hard to justify letting government ignore this knowledge any more than it could ignore scientific knowledge. Hence, just as the liberal has a strong incentive to insist that theological claims are merely matters of irrational commitment, so too does he have a strong incentive to insist that beliefs about “personal morality” are matters of taste, subjective emotional reaction, etc.

In this way too, then, liberalism, at least in its dominant contemporary manifestations, is at odds with the fourth of our fundamental natural inclinations, as it is understood in the A-T tradition. For of course, the A-T natural law tradition holds that there is a great deal of genuine knowledge to be had where matters of “personal morality” are concerned.

Now, the matters of “personal morality” about which contemporary liberalism exhibits such skepticism have largely to do with sex, so that there is an obvious sense in which liberalism tends to be at odds also with the third of our natural inclinations as A-T natural law theorists understand it. But there is another and more specific source of tension between liberalism and this third natural inclination. The family is the most obviously natural form of social organization. It is also the context within which we are most obviously obliged to submit to an authority we never consented to, viz. parental authority. Accordingly, the family sits uneasily with the core liberal ideas that society is artificial and that there can be no authority over an individual to which he has not in some sense consented. There is thus bound to be a strong temptation in liberalism to extent its analysis of society on the large scale to the small scale case of the family. The modern attitude toward marriage and family as essentially about individual personal fulfillment, toward the having of children as an option which a couple may or may not wish to exercise (rather than the reason why the institution of marriage exists in the first place), easy divorce in the name of personal fulfillment, the redefinition of marriage to fit current attitudes about homosexuality, etc. all clearly reflect this tendency to try to make of family something approximating an artificial and contractual arrangement.

The current push for the legalization of assisted suicide indicates that liberalism is not fully consistent even with the second of the five natural inclinations. And the prevalence within liberal societies of moral minimalism, moral skepticism, subjectivism about value, and moral relativism is evidence that liberalism sits poorly even with the first and most basic of the natural inclinations.

This is not to say that all forms of liberalism are in every way, and to the same extent in the case of each inclination, at odds with the five on the list. Much less is it to say that all individual liberals are personally hostile to the general conception of moral life summarized in the A-T account of the five inclinations. All the same, liberalism’s emphasis on individual autonomy has over the centuries been taken in increasingly extreme directions, in ways increasingly at odds with the A-T understanding of the five inclinations.

In recent decades, some Catholics have thought that concepts like “human rights” and the “dignity of the human person” might provide conceptual common ground between liberalism and Catholic moral thinking (the latter having, of course, been deeply influenced by the A-T natural law tradition). This is naïve, because such expressions bear radically different meanings in the minds of liberals on the one hand and Catholic and A-T natural law theorists on the other. For the latter, our dignity lies precisely in our capacity as rational animals to pursue the five natural inclinations, and the function of rights is to safeguard the possibility of pursuing them. For contemporary liberalism, by contrast, our “dignity” and “rights” entail that we may if we wish be indifferent to these inclinations or even opposed to them.

Published on July 28, 2016 11:16

July 24, 2016

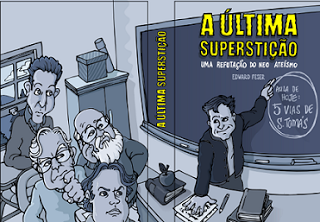

The Last Superstition in Brazil

My book

The Last Superstition

, having appeared a few years back in a German translation, will soon be available in Brazilian Portuguese. The publisher is Edições Cristo Rei, and the book is being kicked off by way of a crowdfunding campaign. The book cover can be seen above. (Yes, that’s me they’ve drawn in front of the blackboard. You can guess who the other guys are.)

My book

The Last Superstition

, having appeared a few years back in a German translation, will soon be available in Brazilian Portuguese. The publisher is Edições Cristo Rei, and the book is being kicked off by way of a crowdfunding campaign. The book cover can be seen above. (Yes, that’s me they’ve drawn in front of the blackboard. You can guess who the other guys are.)

Published on July 24, 2016 18:53

July 18, 2016

Capital punishment at Catholic World Report

Over at Catholic World Report today you’ll find “Why the Church Cannot Reverse Past Teaching on Capital Punishment,” the first installment of a two-part article I have co-authored with Joseph M. Bessette, who teaches government and ethics at Claremont McKenna College. Joe and I recently completed work on our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of the Death Penalty, which is forthcoming from Ignatius Press.The fruit of many years of research and writing, our book is, so far as we know, by far the most thorough and systematic defense of capital punishment yet written from a Catholic point of view, addressing in depth all of the crucial philosophical, theological, and social scientific aspects of the issue. We put forward an exposition and defense of the Thomistic natural law justification of capital punishment and a critique of the “new natural law” position. We offer detailed analysis of the relevant statements to be found in scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the popes, along with an account of the different levels of authority enjoyed by various magisterial statements. We provide an in-depth treatment of the questions of whether the death penalty has significant deterrence value, whether its application in the United States today reflects racial discrimination or discrimination against the poor, whether there is a significant risk of execution of the innocent, whether capital punishment removes the possibility of the offender’s repentance, and whether considerations of retributive justice are still applicable today. We provide a detailed evaluation of the theological and social scientific objections raised in recent years by the American bishops.

Over at Catholic World Report today you’ll find “Why the Church Cannot Reverse Past Teaching on Capital Punishment,” the first installment of a two-part article I have co-authored with Joseph M. Bessette, who teaches government and ethics at Claremont McKenna College. Joe and I recently completed work on our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of the Death Penalty, which is forthcoming from Ignatius Press.The fruit of many years of research and writing, our book is, so far as we know, by far the most thorough and systematic defense of capital punishment yet written from a Catholic point of view, addressing in depth all of the crucial philosophical, theological, and social scientific aspects of the issue. We put forward an exposition and defense of the Thomistic natural law justification of capital punishment and a critique of the “new natural law” position. We offer detailed analysis of the relevant statements to be found in scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the popes, along with an account of the different levels of authority enjoyed by various magisterial statements. We provide an in-depth treatment of the questions of whether the death penalty has significant deterrence value, whether its application in the United States today reflects racial discrimination or discrimination against the poor, whether there is a significant risk of execution of the innocent, whether capital punishment removes the possibility of the offender’s repentance, and whether considerations of retributive justice are still applicable today. We provide a detailed evaluation of the theological and social scientific objections raised in recent years by the American bishops.We demonstrate in our book that the case for preserving capital punishment is very strong, that the case for abolishing it extremely weak, and that the kind of rhetoric that has dominated Catholic discussion of the issue in recent years cannot be reconciled with the irreformable teaching of scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the popes. We do so in a non-polemical way. In recent discussion of capital punishment within Catholic circles there has been far too much emotion and simple-minded sloganeering, and far too little careful reasoning and attention to the actual facts. When the facts and arguments are set out dispassionately, they speak for themselves.

More on the book before long. Part 2 of our article will appear at Catholic World Reportlater this week. Links to previous posts and articles on capital punishment can be found here.

Published on July 18, 2016 11:56

July 12, 2016

Bad lovin’

To love, on the Aristotelian-Thomistic analysis, is essentially to will the good of another. Of course, there’s more to be said. Aquinas elaborates as follows:

To love, on the Aristotelian-Thomistic analysis, is essentially to will the good of another. Of course, there’s more to be said. Aquinas elaborates as follows: As the Philosopher says (Rhet. ii, 4), “to love is to wish good to someone.” Hence the movement of love has a twofold tendency: towards the good which a man wishes to someone (to himself or to another) and towards that to which he wishes some good. Accordingly, man has love of concupiscence towards the good that he wishes to another, and love of friendship towards him to whom he wishes good. Now the members of this division are related as primary and secondary: since that which is loved with the love of friendship is loved simply and for itself; whereas that which is loved with the love of concupiscence, is loved, not simply and for itself, but for something else. (Summa Theologiae I-II.26.4)

Take, for example, your love of Italian food, and your desire to cheer up a depressed friend by taking him out to dinner at an Italian restaurant. Your love of the food would be an instance of what Aquinas calls the “love of concupiscence,” for the food is loved for the sake of some benefit it provides, such as the pleasure it gives you. But your intention to cheer up your friend reflects the “love of friendship” insofar as you love your friend for his own sake, and not merely for the sake of some benefit he provides.

Note that the term “concupiscence” is not being used here in a pejorative way. The “love of concupiscence” is, though “secondary” to the love of friendship, nevertheless by itself perfectly innocent. (“Concupiscence” in the narrower, pejorative sense is not love of a thing for the sake of the benefit it provides one per se, but rather love of that sort which has become disordered.)

Obviously, a person can also be the object of the love of concupiscence. Sexual desire would be a standard example, but we can take pleasure in other people in other ways too, such as when we enjoy being around someone because he is funny, or want to maintain a good relationship with someone because he is a good business contact. Aquinas continues:

When friendship is based on usefulness or pleasure, a man does indeed wish his friend some good: and in this respect the character of friendship is preserved. But since he refers this good further to his own pleasure or use, the result is that friendship of the useful or pleasant, in so far as it is connected with love of concupiscence, loses the character to true friendship. (Summa Theologiae I-II.26.4)

Notice that Aquinas does not say that friendships based on pleasure or usefulness are bad, any more than the love of concupiscence in general is per sebad. His point is that they are not friendships in the strictest sense, because the friend is not loved for his own sake.

Now of course, even when we do love someone for his own sake, we still typically take pleasure in the friendship, we desire to be with the person, and so forth. But it is nevertheless the willing of the other’s good that is what is truly essentialto the love. Aquinas says that “love is spoken of as being… joy [or] desire… not essentially but causally” (Summa Theologiae I-II.26.1). In other words, the pleasure or joy you take in the person, and the desire you have to be with him, are not themselves the love, but rather the effect of the love.

A related point is that, since to love is to willthe good of another, it is essentially active and within our power, rather than entirely passive the way an emotion is passive, even though in us (unlike in God) it has a passive aspect. Writes Aquinas:

[I]n ourselves the intellectual appetite, or the will as it is called, moves through the medium of the sensitive appetite. Hence, in us the sensitive appetite is the proximate motive-force of our bodies. Some bodily change therefore always accompanies an act of the sensitive appetite... Therefore acts of the sensitive appetite, inasmuch as they have annexed to them some bodily change, are called passions; whereas acts of the will are not so called. Love, therefore, and joy and delight are passions; in so far as they denote acts of the intellective appetite, they are not passions. (Summa Theologiae I.20.1)

While pleasant emotions are typically associated with love, then, love can exist without them insofar as one can will another’s good even if that person generates in us no pleasant affective response. This is what happens when, for example, we follow Christ’s command to love our enemies. Christ is not demanding that we have warm feelings toward someone who does us wrong, or even necessarily that we somehow get rid of the negative feelings he generates in us. Those negative feelings are perfectly natural, after all, and often impossible to extirpate. Rather, Christ is saying that, whatever it is we feel, what we will should be the enemy’s good -- which might, by the way, include his being punished (since punishment is in general good for the offender), though always also his repentance.

To summarize, then, we have four main points: First, love is primarily a matter of will rather than passion. Second, pleasant feelings are therefore not of its essence, even if they are usually associated with it. Third, love is a matter of willing what is good for the beloved. Fourth, love of another for his own sake has priority over love of another merely for some benefit he provides.

That much is standard classical and medieval wisdom. But modern people tend to get love badly wrong on all four counts. Not always and consistently, of course, but very often both in practice and notionally.

Perhaps the root error is to confuse the desires and emotional effects or concomitants of love with love itself. Hence modern people almost always characterize love as a “feeling” of a certain sort, and when the feeling is gone conclude that love is gone. Needless to say, this happens most often in the case of marriage, but can occur also with friendships and relations with siblings and other relatives. Hence when the feelings wither or die the relationships often wither and die with them.

Now, feelings of the sort in question are indeed natural and important, and there is no point in denying or minimizing that importance. Nature puts the feelings in us as an aid to the will, and while they are bound to fade to a significant extent, when they have entirely disappeared or even turned negative, something is wrong. It is, perhaps, at least in part in overreaction to too bloodless a conception of marital love that modern people have tended to overemphasize the affective side of things.

All the same, love is primarily a matter of will rather than feeling, so that the modern attitude is simply superficial -- indeed, it is childish, since it is characteristic of childhood to be moved more by feeling than by reason and will, and a mark of maturity to reverse this tendency.

De-emphasizing will and overemphasizing pleasant feelings, it is no surprise that modern people tend also to overemphasize what Aquinas calls the “love of concupiscence,” even to the point of reversing its subordination to the “love of friendship.” For if love is thought to be essentially about having certain pleasant feelings, then the quest for love naturally comes to be understood as essentially a matter of finding someone who will generate in oneself pleasant feelings of the sort in question, and showing love to others comes to be understood as essentially a matter of generating in them pleasant feelings of the sort in question. And insofar as the quest for love is seen as a matter of finding someone who will benefit oneself in this way, love comes to be seen as a matter of self-fulfillment.

Of course, love is indeed in part a matter of self-fulfillment. Spouses fulfill themselves in being good husbands and wives, parents fulfill themselves in being good parents, friends fulfill themselves in being good friends. But such self-fulfillment is an effect or byproduct of love rather than the aim of love. When it becomes the aim, the beloved is no longer loved for his own sake, and the concupiscent tail begins to wag the dog.

Thus do we have the sentimentalization (or Burt Bacharachization) of love, on which a “loving” community or society comes to be understood as a society in which pleasant feelings of a certain sort are widespread. Unsurprisingly, loving one’s enemies comes to seem incompatible with punishing them. For isn’t the will to inflict punishment typically associated with negative feelings toward the one being punished? And doesn’t its infliction cause unpleasant feelings in the one being punished?

Furthermore, where matters of sex are concerned, if pleasant feelings of a romantic or affectionate sort exist between any two people, how could this fail to count as “love,” and thus something any Christian ought to celebrate? And if disapproval of people’s sexual behavior causes in them unpleasant feelings (for example, feelings of guilt, or the unpleasantness associated with being judged), how could such disapproval fail to count as “hatred”?

This is all quite silly given an analysis like Aquinas’s, on which unpleasant feelings can be associated with what is good (for example, getting the punishment one deserves) and pleasant feelings can be associated with what is bad (for example, sexually immoral behavior), and on which love is essentially a matter of the will rather than a matter of having certain feelings. Hence, since love is essentially a matter of willing what is good for someone, it is perfectly possible to love someone while affirming that some behavior that gives him pleasant feelings is bad (as when one disapproves of an adulterous relationship), or while harboring negative feelings about him (as when one finds it agreeable to see a criminal getting his just deserts, even though one also sincerely hopes and prays for that criminal’s repentance).

But that brings us to the last and most grave respect in which modern people go wrong where love is concerned. Love, again, is essentially a matter of willing for someone what is good for him. But modern people often deny that goodness is an objectivefeature of reality; rather, following thinkers like Hobbes and Hume, they often locate goodness in the subjective valuations of the agent, valuations we tend to project onto reality and thus wrongly regard as objective features of the world. (Here too, the claim isn’t that all modern people take this view or do so consistently, but only that this way of thinking is very common in the modern world.)

Now, moral subjectivism and moral relativism are not the same thing, but they are closely related. For one thing, it is difficult to be a moral relativist without being a subjectivist about moral value. For example, if X is good relative to culture A but not good relative to some other culture B, then it is hard to see how the goodness of X could be an objective feature of the world. For if it were, then it seems we’d have to say that culture B is simply wrong about X, and that is just what the moral relativist does not allow for. So it is hard to see how moral relativism can fail to be committed to the view that moral goodness exists only in the subjective valuations of individuals or groups of individuals.

It is also difficult to be a subjectivist about moral value without being a kind of moral relativist. For human beings do not in fact agree in their subjective valuations, and even if they did, there could always in principle have been human beings who had very different ones. Moreover, if moral subjectivism is right, there could be no objective criterion by which to determine which sets of subjective valuations were the “right” ones. So, given moral subjectivism, it is hard to see how to avoid the conclusion that what is morally good is relative to the valuations of individuals and groups of individuals, or at best (if all actual individuals happened as a matter of contingent fact to agree in their subjective valuations) relative to the valuations that all human beings happened as a matter of merely contingent fact to share.

Now, as I argued in a post on relativism, moral relativism is really a kind of eliminativism about morality in disguise. At the end of the day, if moral relativism were true, then it wouldn’t be that moral goodness is a real feature of the world, but is relative to cultures or the like; rather, it would be the case that there simply is no such thing as moral goodness at all, but only the illusion of moral goodness. Now, for reasons like the ones just indicated, I would say that the same thing is true of moral subjectivism. If moral subjectivism were true, then this would entail, not that moral goodness is real, but really something subjective; rather, it would be the case that there simply is no such thing as moral goodness at all, but only the illusion of moral goodness.

When we add subjectivism about goodness to the mix, we can see that the sentimentalization of love in modern times is doubly assured. To love, again, is to will the good of another. But in place of the will, the modern tends to emphasize pleasant feelings and desires; and in place of the good, he tends to put subjective feelings of approval, which can vary from individual to individual. Add in too the radical egalitarianism about feelings and desires toward which democracies tend -- so penetratingly described by Plato in Book VIII of the Republic -- and we have a recipe for the idea that love is pretty much anything anyone wants it to be. Which, come to think of it, pretty much sums up the jurisprudence of Justice Anthony Kennedy (of “sweet mystery of life” fame).

But here’s the kicker. If there really is no such thing as goodness, but only the illusion of it, then -- given that to love is to will the good -- there can really be no such thing as love either, but only the illusion of it. Goodness drops out, and will alone remains; or rather, what remains is will as guided by subjective feelings and desires rather than by any objective standard. The lover becomes, in effect, the man who declares: I will this, period. Or as Woody Allen famously put it, “the heart wants what it wants.”

So, from willing the good of another to the heart wants what it wants. From Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas to Burt Bacharach, Anthony Kennedy, and Woody Allen. That’s the story of -- not exactly the glory of -- modern love.

Further reading:

Love and sex roundup

Published on July 12, 2016 11:27

July 7, 2016

I am overworked, therefore I link

Physicist Lee Smolin and philosopher Roberto Unger think that physics has gotten something really important really wrong. NPR reports.

Physicist Lee Smolin and philosopher Roberto Unger think that physics has gotten something really important really wrong. NPR reports. The relationship between Aristotelian hylemorphism and quantum mechanics is the subject of two among a number of recent papers by philosopher Robert Koons.

Hey, he said he would return. At Real Clear Defense, Francis Sempa detects a revival of interest in General Douglas MacArthur. The New Criterion reviews Arthur Herman’s new book on MacArthur, while the Wall Street Journal and Weekly Standard discuss Walter Borneman’s new book.

At The Catholic Thing, Matthew Hanley discusses Dario Fernandez-Morera’s book The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain.Philosopher of perception Mohan Matthen is interviewed at 3:AM Magazine.

Roger Scruton’s Confessions of a Heretic is excerpted in the Independent and reviewed in the Times, The National , Standpoint , and in the Washington Free Beacon. (Actually, that’s Sir Roger Scruton now.)

Rumors of the death of teleology have been greatly exaggerated. John Farrell reports, at Forbes.

Spiked on David Seed’s recent book on Ray Bradbury.

A little late to the party, but… at Inference, George Scialabba reviews Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos.

Gene Callahan reviews Rodney Stark’s new book on anti-Catholic clichés, at The University Bookman.

The Oxford Philosopher talks to Stephen Boulter.

For director Brian de Palma, it all started with Hitchcock’s Vertigo(which recently overtook Citizen Kane as “best film ever,” or so the critics say).

Travis Dumsday on the value of philosophy of religion.

At The Secular Outpost, Jeffery Jay Lowder criticizes Jerry Coyne’s criticisms of cosmological arguments.

Philosopher Raymond Tallis has a website.

Via YouTube, a lecture by Eleonore Stump on the problem of evil.

The Economist on Scruton on Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung.

Philosopher Dale Tuggy interviews philosopher Timothy Pawl on the subject of Pawl’s new book on Christology (Part 1 and Part 2).

Inverse asks: Was Philip K. Dick a bad writer? He was certainly an oddball, as Alternet recounts. Anyway, the Blade Runner sequel is on track.

One more Scruton item: On Brexit, in print and on video.

Published on July 07, 2016 11:04

June 30, 2016

Prior on the Unmoved Mover

William J. Prior’s

Ancient Philosophy

has just been published, as part of Oneworld’s Beginner’s Guides series (of which my books

Aquinas

and

Philosophy of Mind

are also parts). It’s a good book, and one of its strengths is its substantive treatment of Greek natural theology. Naturally, that treatment includes a discussion of Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover. Let’s take a look.After a lucid exposition of Aristotle’s conception of the universe and how the prime Unmoved Mover fits into it, Prior tells us that “there are at least three objections that could be raised to Aristotle’s cosmology, apart from the obvious ones raised by modern science” (p. 161). The first concerns the “self-absorbed” character of the Unmoved Mover. Since he contemplates only himself, he cannot be said to know or providentially govern the universe.

William J. Prior’s

Ancient Philosophy

has just been published, as part of Oneworld’s Beginner’s Guides series (of which my books

Aquinas

and

Philosophy of Mind

are also parts). It’s a good book, and one of its strengths is its substantive treatment of Greek natural theology. Naturally, that treatment includes a discussion of Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover. Let’s take a look.After a lucid exposition of Aristotle’s conception of the universe and how the prime Unmoved Mover fits into it, Prior tells us that “there are at least three objections that could be raised to Aristotle’s cosmology, apart from the obvious ones raised by modern science” (p. 161). The first concerns the “self-absorbed” character of the Unmoved Mover. Since he contemplates only himself, he cannot be said to know or providentially govern the universe.Prior’s second objection concerns the idea that the Unmoved Mover moves the world by virtue of being a final cause -- in particular, by being that which everything in its own way strives to emulate. A final cause, says Prior, needn’t actually exist in order to be efficacious. For example, the house a carpenter intends to build is the final cause of his activity, and in some sense it explains that activity even before the house is actually constructed. But in that case, why couldn’t the Unmoved Mover function as the explanation of the movement of things even if he doesn’t actually exist?

Prior’s last objection concerns the idea that the Unmoved Mover is pure actuality, without potentiality. Aristotle explains everything else in terms of both potentiality and actuality, and he holds that nothing could be purely potential. So how could there be something which is purely actual, and not the actuality of some potentiality?

Some of these objections can, I think, be dealt with briefly and those who have read what I’ve written about Aristotelian arguments from motion or change to the existence of God (in Aquinas, in Neo-Scholastic Essays , and elsewhere) will know how the responses would go. First, as to Prior’s allusion to science, as modern Thomists have shown, the basic idea of the Aristotelian argument for a divine Unmoved Mover in no way depends on outdated assumptions in Aristotelian physics, astronomy, and cosmology. The theory of actuality and potentiality can easily be extracted from all that, and that is what is essential to the argument.

Second, Prior’s last objection falsely assumes that actuality and potentiality are equally fundamental. But in fact actuality is more fundamental. A potentiality as such is always grounded in some existing actuality. For example, the potentiality that a match has to generate flame and heat is grounded in the fact that it is actually made of phosphorus rather than some other material. Take away the actuality and the potentiality goes with it. But actuality as such is not similarly grounded in potentiality. (Another way to look at it: The debate over whether the distinction between actuality and potentiality is a real distinction is essentially a debate about potentiality rather than about actuality. That is to say, no one denies that actuality is real; what some deny is that potentiality is really anything more than a certain kind of actuality. See Scholastic Metaphysics for a lot more on that subject.)

Hence, unless Prior has some independent argument for the claim that actuality and potentiality are after all equally fundamental aspects of reality, his last objection has no force.