Edward Feser's Blog, page 74

June 23, 2016

Aquinas on capital punishment

Audio versions of many of the talks from the recent workshop in Newburgh, New York on the theme Aquinas on Politics are available online. My talk was on the subject of Aquinas on the death penalty (with a bit at the end about Aquinas’s views about abortion). I say a little in the talk about the forthcoming book on Catholicism and capital punishment that I have co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette. More on that soon.Links to my various articles and blog posts on capital punishment are collected here.

Audio versions of many of the talks from the recent workshop in Newburgh, New York on the theme Aquinas on Politics are available online. My talk was on the subject of Aquinas on the death penalty (with a bit at the end about Aquinas’s views about abortion). I say a little in the talk about the forthcoming book on Catholicism and capital punishment that I have co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette. More on that soon.Links to my various articles and blog posts on capital punishment are collected here.

Published on June 23, 2016 10:29

June 17, 2016

Nagel v Nietzsche: Dawn of Consciousness

While we’re on the subject of Nietzsche: The Will to Power, which is a collection of passages on a variety of subjects from Nietzsche’s notebooks, contains some interesting remarks on consciousness, sensory qualities, and related topics. They invite a “compare and contrast” with ideas which, in contemporary philosophy, are perhaps most famously associated with Thomas Nagel. In some ways, Nietzsche seems to anticipate and agree with points made by Nagel. In other respects, they disagree radically.Nagel has for decades now emphasized that the mind-body problem is an artifact of the way modern natural science characterizes “the physical” and how it understands the notion of explanation of phenomena in physical terms. The objective, mind-independent material world is characterized in entirely quantitativeterms, and whatever does not fit this quantitative description is treated as a mere projection of the mind. In particular, qualitative features like color, sound, taste, smell, etc. as we know them in everyday life, along with purposes or teleological features, are taken to exist only in the conscious experiences of the knowing subject. As Nagel wrote not too long ago in Mind and Cosmos:

While we’re on the subject of Nietzsche: The Will to Power, which is a collection of passages on a variety of subjects from Nietzsche’s notebooks, contains some interesting remarks on consciousness, sensory qualities, and related topics. They invite a “compare and contrast” with ideas which, in contemporary philosophy, are perhaps most famously associated with Thomas Nagel. In some ways, Nietzsche seems to anticipate and agree with points made by Nagel. In other respects, they disagree radically.Nagel has for decades now emphasized that the mind-body problem is an artifact of the way modern natural science characterizes “the physical” and how it understands the notion of explanation of phenomena in physical terms. The objective, mind-independent material world is characterized in entirely quantitativeterms, and whatever does not fit this quantitative description is treated as a mere projection of the mind. In particular, qualitative features like color, sound, taste, smell, etc. as we know them in everyday life, along with purposes or teleological features, are taken to exist only in the conscious experiences of the knowing subject. As Nagel wrote not too long ago in Mind and Cosmos:The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop.(pp. 35-36)

Now, the method in question seems to define the “physical” and the “mental” in such a way that the latter can never be explained in terms of the former, since the former is made exhaustively quantitative and the latter is irreducibly qualitative. The trouble that qualitative features or qualia pose for materialist attempts to explain the mind thus derives, then -- as Nagel famously argued in his 1974 essay “What is it like to be a bat?” and has repeated many times over the years -- precisely from the way materialists themselves conceive of matter, viz. in the exclusively quantitative terms of modern physics. (I’ve discussed Nagel’s argument in detail in several places, e.g. in a series of posts on Mind and Cosmosand its critics.)

Now, some of what Nietzsche writes in The Will to Power seems fairly close to what Nagel says. Consider the following passages (the numbers in the citations below are section numbers rather than page numbers):

“In the development of thought a point had to be reached at which one realized that what one called the properties of things were sensations of the feeling subject: at this point the properties ceased to belong to the thing.” The “thing-in-itself” remained… [A]nalysis revealed that even force was only projected into them, and likewise -- substance.

[T]he physical explanation, which is a symbolization of the world by means of sensation and thought, can in itself never account for the origin of sensation and thought; rather physics must construe the world of feeling consistently as lacking feeling and aim -- right up to the highest human being. And teleology is only a history of purposes and never physical! (562)

Our “knowing” limits itself to establishing quantities; but we cannot help feeling these differences in quantity as qualities. Quality is a perspective truth for us; not an “in-itself.” (563)

[I]n a purely quantitative world everything would be dead, stiff, motionless. -- The reduction of all qualities to quantities is nonsense: what appears is that the one accompanies the other, an analogy -- (564)

Qualities are insurmountable barriers for us; we cannot help feeling that mere quantitative differences are something fundamentally distinct from quantity, namely that they are qualities which can no longer be reduced to one another. But everything for which the word “knowledge” makes any sense refers to the domain of reckoning, weighing, measuring, to the domain of quantity; while, on the other hand, all our sensations of value (i.e., simply our sensations) adhere precisely to qualities… It is obvious that every creature different from us senses different qualities and consequently lives in a different world from that in which we live… (565)

End quote. That reference to “every creature different from us” even calls to mind Nagel’s celebrated example of a bat, which, because it gets around the world via echolocation, has conscious experiences and sensory qualities radically different from ours, and where mere knowledge of the physiology and behavior of a bat will not reveal to us the nature of those qualities and that experience -- thus illustrating the idea that knowledge of the quantitative features focused on by physical science cannot yield knowledge of the qualitative features that define consciousness (whether human consciousness or some other kind of consciousness).

On the other hand, Nietzsche is far less confident than Nagel is that introspection of our conscious experiences reveals anything of ultimate metaphysical significance. For one thing, he thinks the Cartesian ego or subject of experience is illusory (sections 481-492). And in general, he thinks that introspection of our own minds, no less than perception of the external world, really only ever gets us in contact with further representations or interpretations of what it is we are purportedly aware of, rather than with reality:

Critique of modern philosophy: erroneous starting point, as if there existed “facts of consciousness” -- and no phenomenalism in introspection. (475)

“Consciousness” -- to what extent the idea of an idea, the idea of will, the idea of a feeling (known to ourselves alone) are totally superficial! Our inner world, too, “appearance”! (476)

I maintain the phenomenality of the inner world, too: everything of which we become conscious is arranged, simplified, schematized, interpreted through and through -- the actual process of inner “perception,” the causal connection between thoughts, feelings, desires, between subject and object, are absolutely hidden from us -- and are perhaps purely imaginary. The “apparent inner world” is governed by just the same forms and procedures as the “outer” world. We never encounter “facts”… (477)

[N]othing is more phenomenal (or, more clearly:) nothing is so much deception as this inner world which we observe with the famous “inner sense.” (478)

End quote. The concepts by means of which we describe the world of qualia and conscious experience, then, in Nietzsche’s view are no more likely to track reality than the concepts we apply to the outer, physical world. His position seems, accordingly, not unlike that of the contemporary eliminative materialist who takes our mentalistic vocabulary to express mere “folk” notions which might in principle be chucked out wholesale. Indeed, Nietzsche writes:

Consciousness [has] a subsidiary role, almost indifferent, superfluous, perhaps destined to vanish and give way to a perfect automatism…

From the phenomena of the inner sense we conclude the existence of invisible and other phenomena that we would apprehend if our means of observation were adequate and that one calls the nerve current. (523)

Here the idea seems to be, as in contemporary eliminativism, that it might turn out that “nerve currents” and other purely “automatic” physical processes below the level of consciousness are all that exist, with consciousness itself a “superfluous” illusion.

But if introspection of the mental world no more gives us knowledge of reality that perception of the physical world, then, Nietzsche seems to conclude, both the distinction between appearance and reality and that between the material and the immaterial collapse:

Critique of the concept “true and apparent world.” -- Of these, the first is a mere fiction, constructed of fictitious entities.

“Appearance” itself belongs to reality… (568)

The antithesis of the apparent world and the true world is reduced to the antithesis “world” and “nothing.” (567)

We have no categories at all that permit us to distinguish a “world in itself” from a “world of appearance”…

If there is nothing material, there is also nothing immaterial. The concept no longer contains anything. (488)

Hence, while (as we saw in the previous post) Nietzsche would reject contemporary scientism, and while (as we saw above) it seems he would also reject reductionist materialist accounts of consciousness, that is not because he rejects naturalism, but on the contrary because he wants to push through what he regards as a more consistent form of naturalism, an essentially eliminativist form of naturalism -- one that supersedes the distinctions between appearance and reality, truth and error, distinctions which scientism and materialist metaphysics essentially preserve. Instead he proposes looking at “knowledge” as merely a way in which the organism gains power over its environment:

There is no question of “subject and object,” but of a particular species of animal that can prosper only through a… regularity of its perceptions…

Knowledge works as a tool of power. Hence it is plain that it increases with every increase of power…

The utility of preservation -- not some abstract-theoretical need not to be deceived -- stands as the motive behind the development of the organs of knowledge -- they develop in such a way that their observations suffice for our preservation. In other words: the measure of the desire for knowledge depends upon the measure to which the will to power grows in a species: a species grasps a certain amount of reality in order to become master of it, in order to press it into service. (480)

So, the Nietzschean übermensch or Superman may seem thereby to get the upper hand over the Nagelian Batman of traditional metaphysics (specifically neo-Aristotelian metaphysics, in the case of Mind and Cosmos, as I noted in the series of posts on the book). However, as you know if you saw the flick Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the appearance of superior power can be illusory, as Batman ended up inflicting on Superman one of the most delightfully brutal beatdowns in cinematic and comic book history. And the same thing would occur in the case of a Nagel v Nietzsche bout. As we saw in my series of posts on eliminative materialist Alex Rosenberg’s The Atheist’s Guide to Reality, there is simply no way at the end of the day to make an eliminativist position coherent (and I examined attempts to do so in detail).

Nietzsche’s position faces obvious incoherence problems of its own. The very attempt to dismiss the appearance/reality distinction as illusory quite blatantly itself presupposes an appearance/reality distinction, since the very notion of an “illusion” presupposes an appearance that fails to correspond to reality, to the facts, to what is true, etc. Nietzsche’s pitting of his proposed biological account of knowledge-as-will-to-power against traditional metaphysics itself presupposes that this account is true, corresponds to reality, etc. in a way that traditional metaphysical theories do not. And so forth.

That does not mean that Nietzsche is wrong to think that less extreme, reductionist rather than eliminativist forms of naturalism are mistaken. (He is particularly hard on “the mechanistic interpretation of the world” in The Will to Power.) He is notwrong about that. The trouble is that since his own more radical position is even less coherent, the solution is to return to the traditional metaphysics that both positions eschew -- as Nagel does, however partially and tentatively, in Mind and Cosmos.

Published on June 17, 2016 13:17

June 13, 2016

Adventures in the Old Atheism, Part I: Nietzsche

Atheism, like theism, raises both theoretical and practical questions. Why should we think it true? And what would be the consequences if it were true? When criticizing New Atheist writers, I have tended to emphasize the deficiencies of their responses to questions of the first, theoretical sort -- the feebleness of their objections to the central theistic arguments, their ignorance of what the most important religious thinkers have actually said, and so forth. But no less characteristic of the New Atheism is the shallowness of its treatment of the second, practical sort of question.The mentality is summed up perfectly in the notorious “Atheist Bus Campaign” of 2009 and its preposterous slogan: “There's probably no god. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.” As if atheism promised only sweetness and light. As if the vast majority of human beings would not find the implications of atheism -- that human existence has no purpose, that there is no postmortem reward to counterbalance the sufferings of this life, nor any hope for seeing dead loved ones again, etc. -- far more depressing than any purported deficiencies in traditional religious belief. And as if the metaphysical assumptions underlying atheism would not cast into doubt the liberal and egalitarian values upheld by most atheists no less than the more traditional moral codes of the world religions.

Atheism, like theism, raises both theoretical and practical questions. Why should we think it true? And what would be the consequences if it were true? When criticizing New Atheist writers, I have tended to emphasize the deficiencies of their responses to questions of the first, theoretical sort -- the feebleness of their objections to the central theistic arguments, their ignorance of what the most important religious thinkers have actually said, and so forth. But no less characteristic of the New Atheism is the shallowness of its treatment of the second, practical sort of question.The mentality is summed up perfectly in the notorious “Atheist Bus Campaign” of 2009 and its preposterous slogan: “There's probably no god. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.” As if atheism promised only sweetness and light. As if the vast majority of human beings would not find the implications of atheism -- that human existence has no purpose, that there is no postmortem reward to counterbalance the sufferings of this life, nor any hope for seeing dead loved ones again, etc. -- far more depressing than any purported deficiencies in traditional religious belief. And as if the metaphysical assumptions underlying atheism would not cast into doubt the liberal and egalitarian values upheld by most atheists no less than the more traditional moral codes of the world religions. One of the hallmarks of the Old Atheism is that it was less inclined toward such naïveté. You won’t find banalities like “stop worrying and enjoy your life” in writers like Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Sartre, Freud, or Marx. Such thinkers were in general more sensitive to the unpleasant implications of atheism, and to the challenge atheism and its metaphysical presuppositions pose to the hopes and ideals even of many atheists themselves.

Not that this attitude is entirely dead. Woody Allen has been giving expression to it for much of his career ( Crimes and Misdemeanors being the best example, Whatever Works being by far the worst). In recent philosophy, Alex Rosenberg has certainly been willing to draw out from atheism some pretty chilling consequences. David Stove’s atheism was even more consistently pessimistic, and unencumbered by Rosenberg’s capricious desperation to make his own atheistic pessimism as palatable as possible to egalitarian liberals. New Atheists, however, seem in general more inclined toward delusional happy-talk of the kind indulged in by Richard Dawkins when he opined that a world without religion could be “paradise on earth… a world ruled by enlightened rationality… a much better chance of no more war… less hatred… less waste of time.”

So let’s take a look, in this post and future ones, at atheism of the grittier old time sort. We’ll start with Nietzsche, that grandest of Old Atheists and the great hero of my own atheist years. My favorite Nietzsche line back in the day was this:

A very popular error: having the courage of one's convictions; rather it is a matter of having the courage for an attack on one’s convictions! (Cited in Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, p. 354)

You might say that the reason I’m no longer an atheist is that I took Nietzsche’s advice seriously. Of course, your mileage may vary. But what might a New Atheist with the courage for an attack on his own convictions yet learn, even short of giving up his atheism?

The death of God

Nietzsche famously maintained “that ‘God is dead,’ that the belief in the Christian god has become unbelievable” and that this promised “a new dawn” and was thus a cause for “happiness, relief, exhilaration, encouragement” (The Gay Science, Kaufmann translation, pp. 279-80). But he was not so stupid as to think that “paradise on earth,” “a much better chance of no more war,” and other such Dawkinsian fantasies would be the immediate sequel. On the contrary, he foresaw that “shadows… must soon envelop Europe,” that a “sequence of breakdown, destruction, ruin, and cataclysm… is now impending,” indeed a “monstrous logic of terror… an eclipse of the sun whose like has probably never yet occurred on earth” (p. 279).

Likewise, the protagonist of Nietzsche’s famous parable of the madman says:

“Whither is God? … I will tell you. We have killed him -- you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us? … God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

“How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?...” (The Gay Science, p. 181)

Why all the melodrama, if the “death of God” amounts (as the New Atheist would have you believe) to nothing more momentous than (say) a child’s coming to realize that Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and the Flying Spaghetti Monster don’t really exist?

The answer is that, as Nietzsche understood more profoundly than even many religious believers do, a religion is not merely a set of metaphysical propositions but embodies a culture’s highest values and thus a sense of its own worth:

A people that still believes in itself retains its own god. In him it reveres the conditions which let it prevail, its virtues: it projects its pleasure in itself, its feeling of power, into a being to whom one may offer thanks. Whoever is rich wants to give of his riches; a proud people needs a god: it wants to sacrifice. Under such conditions, religion is a form of thankfulness. Being thankful for himself, man needs a god. (The Antichrist, section 16, Kaufmann translation)

Consequently, a culture that doubts its religion comes to doubt itself and its own legitimacy. And a culture that repudiates that religion is, in effect, committing a kind of cultural suicide. The moral and social order to which the religion gave rise cannot survive its disappearance. The trouble, in Nietzsche’s view, is that too few see what this entails:

Much less may one suppose that many people know as yet what this event [the death of God] really means -- and how much must collapse now that this faith has been undermined because it was built upon this faith, propped up by it, grown into it; for example, the whole of our European morality. (The Gay Science, p. 279)

The New Atheist, upon hearing this, may shrug, thinking only of the heady prospect of guilt-free porn surfing, transvestite bathroom access, rectal coitus, and the other strange obsessions of the modern liberal mind. But Nietzsche had somewhat higher ends in view. By “the whole of our European morality,” he was not talking merely or even primarily about the rules of traditional sexual ethics against which the modern liberal has such a weird animus (and which are not unique to Christianity or Europe in any event). He was talking about everything that has counted as morality in European culture, including the values modern egalitarian liberals still prize, and which Kant, Mill, and other modern ethicists of whom Nietzsche is harshly critical tried to give a secular foundation. Since Nietzsche despised that morality, he thought its disappearance was a good thing and opened the door to something better. But he knew that the transition would be ugly, that the path to a new order was uncharted, and that the precise nature of the destination was unclear. Hence:

The time has come when we have to payfor having been Christians for two thousand years: we are losing the center of gravity by virtue of which we lived; we are lost for a while. (The Will to Power 30, Kaufmann and Hollingdale translation. The numbers cited here and later are section numbers, unless otherwise indicated.)

Against equality

What Nietzsche most hated, and the demise of which he most looked forward to, was the egalitarianism that Christianity had introduced into Western civilization. As he writes in The Will to Power:

The “Christian ideal”: … attempt to make the virtues through which happiness is possible for the lowliest into the standard ideal of all values… (185)

Through Christianity, the individual was made so important, so absolute, that he could no longer be sacrificed: but the species endures only through human sacrifice -- All souls become “equal” before God: but this is precisely the most dangerous of all possible evaluations! If one regards individuals as equal, one calls the species into question, one encourages a way of life that leads to the ruin of the species: Christianity is the counterprinciple to the principle of selection…

This universal love of men is in practice the preference for the suffering, underprivileged, degenerate: it has in fact lowered and weakened the strength, the responsibility, the lofty duty to sacrifice men. (246)

What is it we combat in Christianity? That it wants to break the strong… (252)

And in The Antichrist Nietzsche famously says:

What is good? Everything that heightens the feeling of power in man, the will to power, power itself.

What is bad? Everything that is born of weakness.

What is happiness? The feeling that power is growing, that resistance is overcome.

Not contentedness but more power; not peace but war; not virtue but fitness (Renaissance virtue, virtu, virtue that is moraline-free).

The weak and the failures shall perish: first principle of our love of man. And they shall even be given every possible assistance.

What is more harmful than any vice? Active pity for all the failures and all the weak: Christianity. (The Portable Nietzsche, p. 570)

The “equality of souls before God,” this falsehood, this pretext for the rancor of all the base-minded, this explosive of a concept which eventually became revolution, modern idea, and the principle of decline of the whole order of society -- is Christian dynamite. (p. 655)

End quote. Now, about this notion of the equal worth of all human beings, Nietzsche makes two main points. First, it loses all intellectual foundation with the demise of Christianity. He writes, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

[T]hus blinks the mob -- “there are no higher men, we are all equal, man is man; before God we are all equal.”

Before God! But now this god has died. And before the mob we do not want to be equal. (The Portable Nietzsche, p. 398)

And in Twilight of the Idols:

When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one's feet. This morality is by no means self-evident… Christianity is a system, a whole view of things thought out together. By breaking one main concept out of it, the faith in God, one breaks the whole: nothing necessary remains in one's hands… Christian morality is a command; its origin is transcendent… it stands and falls with faith in God. (The Portable Nietzsche, pp. 515-16)

This collapse of any reason to believe in the basic moral equality of all human beings is among the repercussions of the “death” of the Christian God that Nietzsche thinks European civilization has yet to face up to. Modern secular moralists presuppose this egalitarianism but they have no rational grounds for doing so. It is merely a prejudice they have inherited and refuse to question despite their rejection of its traditional basis:

[U]tilitarianism (socialism, democracy) criticizes the origin of moral evaluations, but it believes them just as much as the Christian does. (Naiveté: as if morality could survive when the God who sanctions it is missing!…) (The Will to Power 253)

For Nietzsche, when modern intellectuals “believe that they know ‘intuitively’ what is good and evil, when they therefore suppose that they no longer require Christianity as the guarantee of morality,” this is a delusion, and in fact reflects nothing more than the historical “effects of the dominion of the Christian value judgment and… the strength and depth of this dominion” even if “the origin of [the] morality has been forgotten” (Twilight of the Idols, p. 516).

Think of the contemporary secular academic moral philosopher who appeals to our “intuitions,” the Rawlsian method of bringing moral theory and our “considered convictions” into “reflective equilibrium,” the liberal activist who glibly appeals to the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights as if it were something other than a set of sheer assertions floating in midair, and so forth. All of this, for Nietzsche, would merely confirm his judgment that secular egalitarianism is nothing more than a bundle of sentiments inherited from Christianity and incapable of being given a new rational foundation. (“The democraticmovement,” says Nietzsche in Beyond Good and Evil, “is the heir of the Christian movement” (Kaufmann translation, p. 116). Cf. my argument to the effect that liberalism is essentially a Christian heresy.)

The second main point Nietzsche makes about moral egalitarianism is that there is, in his view, not only no reason to accept it but also positive reason to rejectit. For one thing, he would apply his famous hermeneutics of suspicion and method of genealogical critique to egalitarianism no less than to religious belief. If there is no good positive reason to accept some view but also reason to think that the true source of its appeal is in some way disreputable, then that, in Nietzsche’s view, is good reason to reject it. And there is such a source in the case of egalitarian moral views: They reflect, in Nietzsche’s opinion, nothing more than the interest that weaklings, mediocrities, and failures of every kind have in bringing down or hamstringing those whose power, excellence, and success they resent and envy. Hence, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche has Zarathustra say:

Thus I speak to you in a parable -- you who make souls whirl, you preachers of equality. To me you are tarantulas, and secretly vengeful. But I shall bring your secrets to light; therefore I laugh in your faces with my laughter of the heights…

“What justice means to us is precisely that the world be filled with the storms of our revenge” -- thus [the tarantulas] speak to each other. “We shall wreak vengeance and abuse on all whose equals we are not” -- thus do the tarantula-hearts vow. “And ‘will to equality’ shall henceforth be the name for virtue; and against all that has power we want to raise our clamor!”

You preachers of equality, the tyrannomania of impotence clamors thus out of you for equality: your most secret ambitions to be tyrants thus shroud themselves in words of virtue. Aggrieved conceit, repressed envy -- perhaps the conceit and envy of your fathers -- erupt from you as a flame and as the frenzy of revenge…

Mistrust all who talk much of their justice! … [W]hen they call themselves the good and the just, do not forget that they would be pharisees, if only they had -- power…

[P] reachers of equality and tarantulas… are sitting in their holes, these poisonous spiders, with their backs turned on life, they speak in favor of life, but only because they wish to hurt. They wish to hurt those who now have power…

I do not wish to be mixed up and confused with these preachers of equality. For, to me justice speaks thus: “Men are not equal.” Nor shall they become equal!...

On a thousand bridges and paths they shall throng to the future, and ever more war and inequality shall divide them… Good and evil, and rich and poor, and high and low… (The Portable Nietzsche, pp. 211-13)

Here Nietzsche deploys his famous distinction between “slave moralities” and “master moralities.” A slave morality begins with its adherents’ sense of their own weakness, mediocrity, and lowliness and aims to stigmatize as “evil” anything that contrasts with this, viz. the characteristic traits of those who are powerful, excellent, or noble. A master morality begins with its adherents’ sense of their own strength, excellence, and nobility, and judges as “bad” whatever fails to live up to that standard. Whereas master moralities are essentially about affirming the characteristics of their adherents, slave moralities are essentially about negating the characteristics of their adherents’ opponents.

Nietzsche despises slave moralities but respects master moralities, and thus while be famously advocates going “beyond good and evil,” he also makes it clear that he does not necessarily want to go beyond good and bad. It is the resentment and envy he takes to underlie a slave morality’s use of the epithet “evil” that he criticizes, not the confidence and gratitude that he takes to underlie a master morality’s judgment about what is “bad.” You might say that Nietzsche sees himself as in the business of “speaking truth to powerlessness,” unmasking the ugly motives of those who hide behind the purportedly lofty sentiments of slave morality. To the egalitarian, he says: Don’t try to fool yourself into thinking that you are motivated by “justice.” In reality you are simply a loser, a misfit, a failure who cannot bear the excellence and success of others and for that reason want to tear them down, while enshrouding this revenge-seeking behind a moralizing smokescreen.

Nietzsche thinks that slave moralities are not only rationally unjustified and reflect base motives; he thinks they are harmful. In emphasizing pity for the weak, they seek to eliminate suffering, but in doing so thereby eliminate the preconditions for excellence and only make human beings weaker, softer, and ignoble. To the slave moralist he says:

You want, if possible -- and there is no more insane “if possible” -- to abolish suffering... Well-being as you understand it -- that is no goal, that seems to us an end, a state that soon makes man ridiculous and contemptible -- that makes his destruction desirable.

The discipline of suffering, of great suffering -- do you not know that only this discipline has created all enhancements of man so far? (Beyond Good and Evil 225)

And in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Zarathustra says:

But if you have a suffering friend, be a resting place for his suffering, but a hard bed as it were, a field cot: thus you will profit him best…

Thus be warned of pity… [A]ll great love is even above all its pity; for it still wants to create the beloved…

But all creators are hard. (The Portable Nietzsche, p. 202)

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche sees the logic of the slave moralist’s obsession with pity for those who suffer playing out in nineteenth-century European politics:

Whoever examines the conscience of the European today will have to pull the same imperative out of a thousand moral folds and hideouts -- the imperative of herd timidity: “we want that some day there should be nothing any more to be afraid of!” Some day -- throughout Europe, the will and way to this day is now called “progress.” (201)

We have a different faith; to us the democratic movement is not only a form of the decay of political organization but a form of the decay, namely the diminution, of man, making him mediocre and lowering his value…

The over-all degeneration of man down to what today appears to the socialist dolts and flatheads as their “man of the future”-- as their ideal -- this [is a] degeneration and diminution of man into the perfect herd animal (or, as they say, to the man of the “free society”), this animalization of man into the dwarf animal of equal rights and claims… (203)

The end result of these trends is the undermining of the very preconditions of social order, including a “mistrust of punitive justice (as if it were a violation of those who are weaker…)” (202). He elaborates as follows:

There is a point in the history of society when it becomes so pathologically soft and tender that among other things it sides even with those who harm it, criminals, and does this quite seriously and honestly. Punishing somehow seems unfair to it, and it is certain that imagining “punishment” and “being supposed to punish” hurts it, arouses fear in it. “Is it not enough to render him undangerous? Why still punish? Punishing itself is terrible.” With this question, herd morality, the morality of timidity, draws its ultimate consequence. (201)

Now, it is not difficult to see in Nietzsche’s account of the “tarantulas” and of “slave morality” a description of the Bern-feeling, Wall-Street-Occupying, Social Justice Warrior. It is hardly a stretch to see a condemnation of Rawls’s “difference principle” implicit in Nietzsche’s contempt for the egalitarian’s “preference for the suffering [and] underprivileged” and for the “attempt to make the virtues through which happiness is possible for the lowliest into the standard ideal of all values.” The modern liberal nanny state, and the advocacy of a therapeutic rather than punitive approach to criminal justice, are obviously exactly the sorts of thing Nietzsche has in mind in the passages just quoted from Beyond Good and Evil. Furthermore, as Richard Schacht observes:

Nietzsche’s critique of pity is above all an attack upon the tendency sufferers have… to be overwhelmed by their own suffering and the similar sufferings of others, and in their preoccupation with it to take it to matter more than anything else. (Nietzsche, p. 459)

And such preoccupation is manifest in identity group politics and the tendency of those committed to it to define themselves in terms of their perceived status as victims of oppression.

Yet such left-wing attitudes and policies are embraced by many New Atheists. If Nietzsche is right, these attitudes and policies are not only bad and unfounded, but have their ultimate source in the very Christianity New Atheists claim to oppose. (I would say that they actually involve a massive distortion of the equal human dignity that Christianity affirms, but that is neither here nor there for present purposes. The point is that, whether faithfully conveyed or distorted, the idea was inherited from Christianity.)

Against scientism

Though Nietzsche certainly shares with the New Atheism its commitment to metaphysical naturalism, he would nevertheless reject its scientism -- and in particular its optimism about the ability of science to capture objective, mind-independent reality -- as hopelessly naïve and indeed incompatible with a naturalistic assessment of man’s cognitive powers. Certainly he would be unimpressed by any argument to the effect that the utility of science proves its truth, or more generally that the fact that our cognitive faculties are adaptive shows that they capture objective reality. He writes of beliefs that are

so much a part of us that not to believe in it would destroy the race. But are they for that reason truths? What a conclusion! As if the preservation of man were a proof of truth! (The Will to Power 497)

Again, he says:

Life is no argument. The conditions of life might include error. (The Gay Science 121)

Nietzsche here anticipates an element of the “argument from reason” later developed by writers like Karl Popper, C. S. Lewis, and Alvin Plantinga (though of course he doesn’t draw the anti-naturalistic conclusion that Lewis and Plantinga do). Survival value must not, in his view, be confused with truth; the idea that science gives us truth rests on a “metaphysical faith” (The Gay Science344).

Furthermore (and as other writers with no theological ax to grind have emphasized) the very notion of a scientific “law of nature” has a theological origin, and in Nietzsche’s view retains a merely metaphorical significance when the theology is jettisoned. There cannot be a true “law” or “regularity” where there is neither a lawgiver nor a subject which literally submits to the law:

Let us beware of saying there are laws in nature. There are only necessities: there is nobody who commands, nobody who obeys, nobody who trespasses. (The Gay Science, p. 168)

“[N]ature’s conformity to law,” of which you physicists talk so proudly, as though -- why, it exists only owing to your interpretation and bad “philology.” It is no matter of fact, no “text,” but rather only a naively humanitarian emendation and perversion of meaning… (Beyond Good and Evil 22)

And again, in The Will to Power:

“Regularity” in succession is only a metaphorical expression, as if a rule were being followed here; not a fact. In the same way “conformity with a law.” We discover a formula by which to express an ever-recurring kind of result: we have therewith discovered no “law,” even less a force that is the cause of the recurrence of a succession of results. That something always happens thus and thus is here interpreted as if a creature always acted thus and thus as a result of obedience to a law or lawgiver, while it would be free to act otherwise were it not for the “law.” (632)

Form, species, law, idea, purpose -- in all these cases the same error is made of giving a false reality to a fiction, as if events were in some way obedient to something… (521)

A major theme of The Will to Power’s treatment of science is the idea that, despite having largely stripped from our notion of nature that which reflects the contingent perspective of the observer, physics still -- insofar as it rests on sensory evidence -- inevitably reflects that perspective to some extent. Of course, to remedy this, physics tries to frame its description of nature in the abstract language of mathematics. But Nietzsche anticipates Bertrand Russell’s theme (to which I have often called attention) that insofar as physics gives us only knowledge of the physical world’s mathematical structure, it does not give us knowledge of the intrinsic character of that which has that structure, and thus actually tells us relatively little about objective reality.

Because we have to think in terms of there being something which has the structure, the physicist postulates certain entities as the relata whose relationships are described in the structural description -- Nietzsche gives atoms as an example. This can lead us to think we’ve actually captured something of the inner nature of the physical world as it is in itself, but in Nietzsche’s view this is an illusion. He writes, in The Will to Power:

To comprehend the world, we have to be able to calculate it; to be able to calculate it, we have to have constant causes; because we find no such constant causes in actuality, we invent them for ourselves -- the atoms. This is the origin of atomism.

The calculability of the world, the expressibility of all events in formulas -- is this really "comprehension"? How much of a piece of music has been understood when that in it which is calculable and can be reduced to formulas has been reckoned up? (624)

It is an illusion that something is known when we possess a mathematical formula for an event: it is only designated, described; nothing more! (628)

Mechanistic theory can… only describe processes, not explain them. (660)

Much more could be said, but I’ll leave it at that. If Nietzsche is right, the New Atheist is hopelessly naïve in supposing that the demise of religion promises only sweetness and light, that liberal egalitarian ideals can or ought to survive the demise of Christianity, and that science gives us much in the way of objective knowledge. New Atheists are notoriously resistant to hearing out an “attack on [their] convictions” when it comes from a religious believer. Are they willing to consider one raised by an Old Atheist?

Published on June 13, 2016 13:02

June 6, 2016

Four Causes and Five Ways

Noting parallels and correlations can be philosophically illuminating and pedagogically useful. For example, students of Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) philosophy are familiar with how soul is to body as form is to matter as act is to potency. So here’s a half-baked thought about some possible correlations between Aquinas’s most general metaphysical concepts, on the one hand, and his arguments for God’s existence on the other. It is well known that Aquinas’s Second Way of arguing for God’s existence is concerned with efficient causation, and his Fifth Way with final causation. But are there further such parallels to be drawn? Does each of the Aristotelian Four Causes have some special relationship to one of the Five Ways? Perhaps so, and perhaps there are yet other correlations to be found between some other key notions in the overall A-T framework.Consider first the most general concepts of A-T metaphysics and their interrelations. As I suggest in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, the entire edifice is grounded in the distinction between act and potency (or actuality and potentiality), which I spell out in chapter 1 of that book (after the prolegomenon of chapter 0, which refutes scientism etc.). Chapter 2 then shows how, from the theory of act and potency, we can derive the notions of efficient causality and final causality. Efficient causality involves the actualization of potency. Final causality enters the picture insofar as a potency is always directed toward a certain outcome or range of outcomes as toward an end.

Noting parallels and correlations can be philosophically illuminating and pedagogically useful. For example, students of Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) philosophy are familiar with how soul is to body as form is to matter as act is to potency. So here’s a half-baked thought about some possible correlations between Aquinas’s most general metaphysical concepts, on the one hand, and his arguments for God’s existence on the other. It is well known that Aquinas’s Second Way of arguing for God’s existence is concerned with efficient causation, and his Fifth Way with final causation. But are there further such parallels to be drawn? Does each of the Aristotelian Four Causes have some special relationship to one of the Five Ways? Perhaps so, and perhaps there are yet other correlations to be found between some other key notions in the overall A-T framework.Consider first the most general concepts of A-T metaphysics and their interrelations. As I suggest in

Scholastic Metaphysics

, the entire edifice is grounded in the distinction between act and potency (or actuality and potentiality), which I spell out in chapter 1 of that book (after the prolegomenon of chapter 0, which refutes scientism etc.). Chapter 2 then shows how, from the theory of act and potency, we can derive the notions of efficient causality and final causality. Efficient causality involves the actualization of potency. Final causality enters the picture insofar as a potency is always directed toward a certain outcome or range of outcomes as toward an end. Chapter 3 goes on to show how form and matter, which are the main constituents of a physical substance, also follow from the theory of act and potency. Prime matter, which is the material cause of a physical substance, is the pure potentiality for the reception of form. Substantial form, which is the formal cause of a material substance, is what actualizes prime matter. Chapter 4 then shows how the distinction between essence and existence, which (unlike the distinction between form and matter) applies to immaterial substances as well as to physical substances, also follows from the theory of act and potency. The essence of a thing is, by itself, merely potential; existence is what actualizes that potential so that we have a concrete substance.

So, we have the following six fundamental A-T concepts: the act/potency distinction; efficient cause; final cause; formal cause; material cause; the essence/existence distinction.

Now consider Aquinas’s arguments for God’s existence (which I discuss and defend in detail in chapter 3 of Aquinas ). The first of the Five Ways is the argument from motion or change to a divine Unmoved Mover. The Second Way is the argument from the existence of series of efficient causes to a divine Uncaused Cause. The Third Way begins from the fact that things come into being and pass away and argues for an absolutely Necessary Being. The Fourth Way argues from the degrees of perfection to be found in things to the existence of a Most Perfect Being. The Fifth Way argues from the existence of final causes to a divine Supreme Intelligence which directs things to their ends.

Aquinas also famously presents, in On Being and Essence, an argument from the existence of things in which there is a distinction between essence and existence to a divine cause which is Subsistent Being Itself. This is sometimes called “the existential proof” and its relationship to the Five Ways is unclear. In AquinasI suggested that the argument corresponds to the Second Way, but that is certainly not obvious, and not everyone would agree with the suggestion. As what I say below indicates, a case could certainly be made for reading it another way.

Hence, we (arguably) have in Aquinas at least six different arguments for God’s existence: the Five Ways plus the “existential proof.”

Perhaps you see where this is going. Is there an interesting correlation between the six fundamental A-T metaphysical notions, on the one hand, and the six arguments for God’s existence on the other? Arguably so.

Motion or change entails, for A-T, the actualization of potency, so the First Way naturally correlates with the theory of act and potency. The Second Way, as already noted, naturally correlates with the notion of efficient causality.

What about the Third Way? Well, the way it gets to an absolutely Necessary Being is by beginning with things that are the opposite of that -- that is to say, with things that are generated and corrupted, which come into being and pass away. Note that (contrary to what many modern discussions of the Third Way imply) these are not exactly the same things as “contingent beings” in the contemporary sense of that term. When contemporary philosophers talk about a “contingent” thing, what they mean is a thing which might in principle not exist. Angels would in this sense be contingent, since although they are immaterial substances and thus incorruptible, they could have failed to exist had God not created them. For Aquinas, by contrast, angels are necessary rather than contingent, precisely because they are incorruptible in the sense that nothing in the natural order of things can destroy them. What differentiates them from God is that they still have to be created and sustained in being by God, so that they have necessity in only a derivative rather than absolute way. Obviously, then -- and as some critics of the Third Way do not realize, leading them to get the argument seriously wrong -- Aquinas does not use the word “necessary” the way contemporary philosophers do. And to start with something like an angel would for him therefore not be a good way to start an argument like the Third Way.

What he starts with are things that are material and thus corruptible in a way immaterial substances are not. Hence the Third Way plausibly correlates with the notion of material cause. That is to say, just as the First Way essentially begins with the notion of act and potency and works to God as the purely actual actualizer of potency, and the Second Way begins with the notion of efficient cause and works to God as the source of all merely derivative efficient causal power, the Third Way essentially begins with the corruptibility entailed by the notion of material cause and works to God as what is absolutely incorruptible and thus necessary in the strongest possible sense.

The Fourth Way is famously the most Platonic-sounding of the Five Ways. Aquinas’s account of how what has goodness in only a limited way participates in that which is Goodness Itself, that which has being in only a limited way participates in that which is Being Itself, etc. calls to mind Plato’s account of how things are what they are because they participate in the Forms. Of course, Aquinas is an Aristotelian rather than a Platonist -- and thus has an Aristotelian rather than Platonic conception of form -- and (as I argue in Aquinas) what are in view in the Fourth Way are, specifically, what the medievals called the Transcendentals (being, goodness, truth, etc.), and not just any old thing for which Plato thinks there is a Form. Still, there is arguably a special correlation between the Fourth Way and the notion of formal causation.

The Fifth Way, as already noted, obviously correlates with the notion of final causality. And the “existential proof” obviously correlates with the distinction between essence and existence. If the existential proof really is (contrary to what I suggested in Aquinas) a distinct argument from the Second Way, the basis of the distinction might be this: While both arguments are concerned with explaining the existence of things and both arrive at God as the ultimate explanation of their existence, the manner of approach is different in each case. The Second Way approaches the issue by way of the notion of the efficient causation of a thing’s existence; the existential proof approaches the issue by way of the notion of a thing’s essence/existence composition.

If all of this is correct, then the idea is that from each of the six basic explanatory notions, we can work to God as ultimate explanation. And the correlations would, again and in summary, be as follows:

Act/potency → First Way

Efficient cause → Second Way

Material cause → Third Way

Formal cause → Fourth Way

Final cause → Fifth Way

Essence/existence → Existential proof

Again, though, I present this as at most half-baked. Perhaps further reflection would complete the baking process and give us a well worked out and defensible set of correlations along these lines. But perhaps it would instead result in somewhat different or somewhat looser correlations, or show that only the more obvious correlations (e.g. between the Second Way and efficient causation, the Fifth Way and final causation) are really defensible.

Published on June 06, 2016 12:06

May 30, 2016

Linking for thinking

Busy week and a half coming up, but I’d never leave you without something to read.

Busy week and a half coming up, but I’d never leave you without something to read. Nautilus recounts the debate between Bergson and Einstein about the nature of time.

Preach it. At Aeon, psychologist Robert Epstein argues that the brain is not a computer.

A new Philip K. Dick television anthology series is planned. In the meantime, gear up for season 2 of The Man in the High Castle.

John Haldane has been busy in Australia: a lecture on sex, a lecture on barbarism, a Q and A, and an essay on transgenderism and free speech. Full report from The Catholic Weekly.New books for Thomists: Eleonore Stump, The God of the Bible and the God of the Philosophers ; Brian Davies, Thomas Aquinas's Summa Contra Gentiles: A Guide and Commentary ; and William Jaworski, Structure and the Metaphysics of Mind: How Hylomorphism Solves the Mind-Body Problem .

The Weekly Standard on art critic Robert Hughes.

Tim Crane on the life and character of Wittgenstein, at the The Times Literary Supplement.

John Searle on perception: Interview at The Partially Examined Life.

Mariska Leunissen’s edited volume Aristotle’s Physics: A Critical Guide is reviewed at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

At OUPblog, William Jaworski on Aristotle and Hilary Putnam.

Has Aristotle’s tomb been found?

Also at Aeon, Elliott Sober asks: Why should we accept Ockham’s Razor?

The Scholasticum is a new post-graduate institute for the study of Scholastic theology and philosophy.

Some more new books: Brant Pitre, The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ ; Matthew Levering, Proofs of God: Classical Arguments from Tertullian to Barth ; and Jim Slagle, The Epistemological Skyhook: Determinism, Naturalism, and Self-Defeat .

An interview with Harvard’s Harvey Mansfield about students today.

The other footnote drops. At First Things, philosopher Michael Pakaluk on Pope Francis’s Amoris Laetitia.

The University Bookman on C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity.

Philosopher and psychologist Daniel Robinson is interviewed at 3:AM Magazine.

Published on May 30, 2016 13:00

May 26, 2016

Self-defeating claims and the tu quoque fallacy

Some philosophical claims are, or at least seem to be, self-defeating. For example, an eliminative materialist who asserts that there is no such thing as meaning or semantic content is implying thereby that his own assertion has no meaning or semantic content. But an utterance can be true (or false) only if it has meaning or semantic content. Hence the eliminative materialist’s assertion entails that it is itself not true. (I’ve addressed this problem, and various futile attempts to get around it, many times.) Cognitive relativism is also difficult to formulate in a way that isn’t self-defeating. I argue in

Scholastic Metaphysics

that scientism, and Hume’s Fork, and attempts to deny the existence of change or to deny the principle of sufficient reason, are also all self-defeating. This style of criticism of a position is sometimes called a retorsion argument.At a conference I was at not too long ago, one of the participants suggested that an appeal to a retorsion argument amounts to a

tu quoque fallacy

(or “appeal to hypocrisy”). A tu quoque fallacy is committed when someone rejects a claim merely because the person advancing the claim acts in a way that is inconsistent with it. For example, if I try to convince you that it is not a good idea to drink to excess and you say “But you drink to excess all the time! Therefore I can dismiss what you’re saying,” you would be committing a tu quoquefallacy. That someone is a hypocrite doesn’t show that what he is saying is false. But don’t retorsion arguments amount to such an appeal to hypocrisy?

Some philosophical claims are, or at least seem to be, self-defeating. For example, an eliminative materialist who asserts that there is no such thing as meaning or semantic content is implying thereby that his own assertion has no meaning or semantic content. But an utterance can be true (or false) only if it has meaning or semantic content. Hence the eliminative materialist’s assertion entails that it is itself not true. (I’ve addressed this problem, and various futile attempts to get around it, many times.) Cognitive relativism is also difficult to formulate in a way that isn’t self-defeating. I argue in

Scholastic Metaphysics

that scientism, and Hume’s Fork, and attempts to deny the existence of change or to deny the principle of sufficient reason, are also all self-defeating. This style of criticism of a position is sometimes called a retorsion argument.At a conference I was at not too long ago, one of the participants suggested that an appeal to a retorsion argument amounts to a

tu quoque fallacy

(or “appeal to hypocrisy”). A tu quoque fallacy is committed when someone rejects a claim merely because the person advancing the claim acts in a way that is inconsistent with it. For example, if I try to convince you that it is not a good idea to drink to excess and you say “But you drink to excess all the time! Therefore I can dismiss what you’re saying,” you would be committing a tu quoquefallacy. That someone is a hypocrite doesn’t show that what he is saying is false. But don’t retorsion arguments amount to such an appeal to hypocrisy?No, they don’t. As every logic and critical thinking teacher knows, one of the problems one encounters in teaching about the logical fallacies is that students often settle into too crude an understanding of what a fallacy involves, and thus tend to see fallacies where there are none. Not every use of language which has emotional connotations amounts to a fallacy of appeal to emotion. Not every attack on a person amounts to an ad hominem fallacy. Not every appeal to authority is a fallacious appeal to authority. A reductio ad absurdum argument should not be confused with a slippery slope fallacy. And so on.

In the same way, by no means does every reference to an opponent’s inconsistency amount to a tu quoque fallacy. On the contrary, pointing out that a certain view leads to inconsistency is a standard technique of logical criticism. It is, for example, what a reductio ad absurdum objection involves, and no one can deny that reductio is a legitimate mode of argumentation. The problem with tu quoque arguments isn’t an appeal to inconsistency as such. The problem is that the specific kind of inconsistency the arguer appeals to is not relevant to the specific topic at issue.

So, suppose I am a drunkard but I tell you that it is bad to be a drunkard, on the basis of the fact that being a drunkard is undignified, is damaging to one’s health, prevents one from holding a job and providing for one’s family, etc. My hypocrisy is irrelevant to the truth of the claim I am making, because the proposition:

(1) Feser is a drunkard.

is perfectly compatible, logically speaking, with the proposition:

(2) It is bad to be a drunkard.

and perfectly compatible also with the proposition:

(3) Being a drunkard is undignified, is damaging to one’s health, prevents one from holding a job and providing for one’s family, etc.

Hence to reject (2), or to reject the argument from (3) to (2), on the basis of (1), is unreasonable. But that is exactly what the person in my example who commits the tu quoque fallacy does.

A retorsion argument is not like that at all. Consider the objection, raised against Eleatic philosophers like Parmenides or Zeno, that they cannot coherently deny that change occurs. The idea here is that the Eleatic is committed to the proposition:

(4) There is no such thing as change.

but at the same time, carries out an act -- for example, the act of reasoning to that conclusion from such-and-such premises, where this very act itself involves change -- which entails the proposition:

(5) There is such a thing as change.

Now (4) is not logically compatible with (5). What we have here is a “performative self-contradiction” in the sense that the very act of defending the position entails the falsity of the position. So, it is not mere hypocrisy, but rather implicit logical inconsistency, that is at issue.

Here’s another way to think about it. Could being a drunkard still be a bad thing, even if I am in fact a drunkard myself? Of course. That’s why it is a tu quoquefallacy to reject my claim that being a drunkard is bad, merely because I am myself a drunkard. But could change really be an illusion, if Parmenides is in fact reasoning from the premises of his argument to the conclusion? No. That’s why it is not a tu quoque fallacy to reject Parmenides’ denial that change occurs on the basis of the fact that he has to undergo change himself in the very act of denying it.

Of course, Parmenides might respond: “Ah, but that assumes that I really am reasoning from premises to conclusion, and I would deny that I am doing so, precisely because that would be an instance of change! So, you are begging the question against me!”

But, first, even if the critic’s retorsion argument against Parmenides did amount to begging the question, it still would not amount to a tu quoque fallacy.

And second, it does not in fact amount to begging the question. The critic can say to Parmenides: “Parmenides, you were the one who presented me with this argument against the reality of change. I merely pointed out that since the rehearsal of such an argument is itself an instance of change, you are yourself already implicitlycommitted to its reality, despite your explicit denial of it. I am pointing out a contradiction in your own position, not bringing in some question-begging premise from outside it. So, if you want to rebut my criticism, it is no good for you to accuse me of begging the question. Rather, you have to show how you can restate your position in a way that avoids the implicit contradiction.”

Of course, no such restatement is forthcoming, because the very act of trying to formulate it would involve Parmenides in exactly the sort of implicit contradiction he was trying to avoid. But that would be his problem, not his critic’s problem. (Eliminativism is, of course, in exactly the same boat -- as I show in some of the posts linked to above -- as are some of the other claims against which retorsion arguments might be deployed.)

Published on May 26, 2016 15:01

May 22, 2016

Putnam and analytical Thomism, Part II

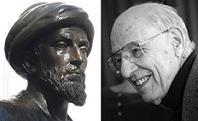

In a previous post I examined the late Hilary Putnam’s engagement with the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition on a topic in the philosophy of mind. Let’s now look at what Putnam had to say about Aristotelian-Thomistic ideas in natural theology. In his 1997 paper “Thoughts Addressed to an Analytical Thomist” (which appeared in an issue of The Monist devoted to the topic of analytical Thomism), Putnam tells us that while he is not an analytical Thomist, as “a practicing Jew” he could perhaps be an “analytic Maimonidean.” The remark is meant half in jest, but that there is some truth in it is evident from what Putnam says about the topics of proofs of God’s existence, divine simplicity, and theological language.

In a previous post I examined the late Hilary Putnam’s engagement with the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition on a topic in the philosophy of mind. Let’s now look at what Putnam had to say about Aristotelian-Thomistic ideas in natural theology. In his 1997 paper “Thoughts Addressed to an Analytical Thomist” (which appeared in an issue of The Monist devoted to the topic of analytical Thomism), Putnam tells us that while he is not an analytical Thomist, as “a practicing Jew” he could perhaps be an “analytic Maimonidean.” The remark is meant half in jest, but that there is some truth in it is evident from what Putnam says about the topics of proofs of God’s existence, divine simplicity, and theological language. Putnam is not unsympathetic to some of the traditional arguments for God’s existence, such as those defended by Aquinas and Maimonides. He rejects the assumptions, common among contemporary secular academic philosophers, that such arguments are uniformly invalid, question-begging, or otherwise fallacious, and that it is absurd even to try to prove God’s existence. He notes the double standard such philosophers often bring to bear on this subject:[T]he majority of these philosophers take it to be quite clear what a “proof” is: a demonstration that something is the case using the standards (or supposed standards) of, if not science, then, let us say, analytic philosophy. In addition, it is supposed that a sound proof ought to be able to convince any rational person who sees it. (Why the arguments of analytic philosophers themselves -- not even the philosophical, as opposed to technical logical, arguments of Frege, or Russell, or Quine, or Davidson, or David Lewis -- all fail to meet this test is not something that analytical philosophers discuss a great deal.) (pp. 487-88)

Putnam also says that “the view that the traditional proofs are fallacious rests, I think, on a straw-man idea of what those proofs are” (p. 488). In fact, he holds, “each of the traditional proofs can be stated in a form in which it proceeds validly from its premisses [and] ones which… are not simply question-begging…” even if an atheist would not accept the premises (Ibid.). In particular, Putnam thinks that causal proofs like those of Maimonides and Aquinas can be given such a form. And he thinks that the proofs’ contention that any ultimate explanation of the world of contingent things requires a necessary cause, and that this necessity is not merely conceptual, reflects “a very natural conception of reason itself” which “expresses intuitions which are very deep in us” and that the notion that modern science has somehow “refuted” these intuitions “deserves critical examination” (p. 489).

Indeed, in Putnam’s view, the notion that science has refuted religion reflects “a deeply confused understanding of what real religious belief is,” because religious belief is not a matter of trying to explain or predict this or that particular empirical phenomenon, and because theological and scientific modes of description are “incommensurable” (though he cautions that he does not mean to be bringing to bear everything Thomas Kuhn famously had in mind when using that term) (p. 491). This brings Putnam to the topic of theological language, and in particular to accounts like Maimonides’ negative theology and Aquinas’s notion of the analogical use of language.

The development of such accounts reflects the fact that, as Putnam puts it, “the monotheistic religions passed -- irreversibly, I believe -- from thinking of God in anthropomorphic terms to thinking of God as a transcendent being” (p. 493). Putnam notes that some contemporary religious thinkers seem to have forgotten the reasons for this development. He cites “a distinguished Christian philosopher” -- Putnam doesn’t name the person -- who once opined to Putnam that worries about theological language were due to a “hang-up” the medievals had about divine simplicity. When asked by Putnam whether God might be said, then, to have distinct states of consciousness which succeed each other in time, this philosopher responded “Why not?” When Putnam suggested that thereby putting God within time would implicitly be to deny God’s transcendence, this philosopher, Putnam says, had no reply.

In fact, in Putnam’s view, the medievals’ concern with divine simplicity was no mere “hang-up” but has a serious theological basis. Giving up simplicity threatens not only God’s transcendence but his necessity too, and thus threatens to turn God into a mere “gaseous vertebrate” (as Putnam puts it, borrowing a vivid phrase from Haeckel), one mere creature alongside others. But divine simplicity does make theological language problematic, which is what led thinkers like Maimonides and Aquinas to their respective theories of such language.

So far Putnam sounds very close indeed to a Thomist, speaking up as he does for a correct understanding of causal proofs of God’s existence and for the classical theist conception of God’s nature. However, he refrains from going the whole hog, in two respects. For one thing, though he thinks that theological language is, despite its problematic nature, both intelligible and different from other sorts of language, he is skeptical of both Maimonides’ and Aquinas’s specific ways of understanding it. For another, he seems to think the Thomist position a bit too rationalist.

Consider first Putnam’s criticisms of Maimonides’ and Aquinas’s accounts of theological language. Putnam briefly comments that Maimonides’ negative theology “leaves it unintelligible why we should say the things we do about God” (p. 495). He does acknowledge that Maimonides allows that we can speak of God in terms of his different actions, but to Putnam this “seems like a failure to carry though his negative theology to the end” (p. 496). (Putnam had more to say about Maimonides’ negative theology in another 1997 article, in Faith and Philosophy.)

Regarding Aquinas’s account of analogical language about God, Putnam thinks that, at least read one way, it collapses into Maimonides’ position that we can speak of God in terms of his actions. But this, I think, is not correct. As I understand Maimonides’ account of our talk about God’s actions (which I discussed in this post from a couple of years ago), when we speak of God’s various actions we are in the strict sense not really saying anything about God himself, but rather only about his effects. But on Aquinas’s analogical account of theological language, we are (at least often) saying things about God himself, and not just about his effects (even if the different predications we make do not pick out distinct parts of God). That is to say, on Maimonides’ position, theological language, even in the case of descriptions of divine action, does not really tell us anything positive about the divine nature itself, whereas for Aquinas it does, at least to a limited extent.

However, Putnam does also consider the role “proportion” plays in Aquinas’s conception of analogical language, and offers as an example the claim that God’s knowledge is to God as Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates. But the problem with this, Putnam says, is that there is no single way Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates, and surely God’s knowledge is not to God in every way that Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates.

The trouble with Putnam’s objection, though, is that it is difficult to know what to make of it, because it is underdeveloped. Both his description of Aquinas’s position and his criticism of it are brief and vague.

The kind of proportionality that Thomists think is relevant to understanding theological language is what is called proper proportionality, of which there are three key features. First, with the analogy of proper proportionality, a term is being used to name something that is intrinsic to all the things being referred to. For example, when we say that a plant, an animal, a human being, an angel, and God all have life, we are using the term “life” analogically, but we are nevertheless referring to something intrinsic to each of the things talked about. (Contrast this with the analogy of attribution, where a term is not being used to name something intrinsic to all the things referred to. For instance, if I say that Socrates is healthy and that his food is healthy, it is only Socrates who has health intrinsically, and his food is “healthy” only insofar as it causes health in him.)

Secondly, with the analogy of proper proportionality, a term is being used literally rather than metaphorically. In the example just referred to, each of the things named is literallysaid to have life, even if “life” is not being used univocally or in exactly the same sense. (Contrast this with the analogy of improper or metaphorical proportionality, as when we say “That tree is an oak” and “Wyatt is an oak” -- meaning, in the second case, not that Wyatt is literally a kind of tree, but that he has a steadfast character.)

The third feature (and the one Putnam cursorily refers to) is that with the analogy of proper proportionality, a term is not being used to name something that is exactly the same in each thing being talked about (as it is when we are speaking in a univocal way) but rather to name something in one that bears a “proportional similarity” to something that exists in another. For example, when I say that “I see the desk in front of me” and “I see that Aquinas’s argument is valid,” the term “see” is not being used univocally, since the “seeing” the eyes do is very different from the “seeing” that the intellect does. Still, the eyes are to a tree as the intellect is to the validity of an argument, so that the word “seeing” properly applies to both. (See pp. 256-63 of my Scholastic Metaphysics for further discussion of analogical language.)

Now, with all of this in mind, what exactly is Putnam’s objection? He says that there is no single way Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates, and that God’s knowledge is not to God in every way that Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates. But what exactly is it that he has in mind that would apply to the case of Socrates but not to the case of God? In particular, if we exclude features that some things have only relationally rather than intrinsically, or only metaphorically rather than literally -- as we would have to do when we are talking about the analogy of proper proportionality rather than the analogy of attribution or the analogy of improper proportionality -- what exactly is left that Putnam thinks would still apply in the case of Socrates but not in the case of God? Moreover, even if God’s knowledge is not to God in every way that Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates, why wouldn’t there being someways that God’s knowledge is to God as Socrates’ knowledge is to Socrates suffice to justify the predication of knowledge to God according to the analogy of proper proportionality?

Putnam doesn’t address such questions, so, again, it is hard to know what to make of his objection.

Now, despite his criticisms of Aquinas, Putnam nevertheless holds that it is possible to talk intelligibly about God, that we have to understand theological language as “sui generis” rather than either equivocal or straightforwardly univocal, and that contrary to the simplistic conception of the literal use of language presupposed by too many contemporary philosophers, “there is no oneform of discourse which is in some absolute sense ‘literal’” (p. 497, emphasis added). So far that might make his position sound close to Aquinas’s view of analogical language after all. But Putnam also says:

In my view, if there is one thing that there isn’t going to be a scientific theory of (either in the Aristotelian or in the contemporary sense of “scientific theory”) it is how religious language works, and how it connects us to God. (p. 497)

and

I feel that insofar as I have any handle on these notions, I have a handle on them as religious notions, not as notions which are supported by an independent philosophical theory. (Certainly not by the theory of Aristotle’s Metaphysics.) For me the “proofs” show conceptual connections of great depth and significance, but they are not a foundation for my religious belief… Nor are “proofs” the way in which I would try to bring someone else to Judaism, or to religious belief of any kind. (p. 490)

It is this resistance to theory, and to understanding philosophy as an intellectual bridge between the religious believer and the non-believer, that marks the key difference between Putnam and Thomism. As he sums up his position: