Gordon Grice's Blog, page 82

September 3, 2011

Predator Takes Dog

Cougar? Bobcat? The biggest bobcats go about a yard long and 35 pounds and are capable of taking young or injured deer, as well as sheep and pigs. Cougar are bigger than that. Both have been known to take pets. A bobcat is more likely in this area (Denton, Texas), but the dog owner said it was a big animal.

The article makes an interesting connection between this summer's heat and drought and changing animal behavior. That global warming thing so many people have been trying not to believe in has already produced some odd changes in the animal world, including, apparently, population explosions among jellyfish. This year has made the change palpable enough to satisfy any skeptic—I hope. It wil be interesting to see what other changes the new climate brings.

No relief in sight | Denton Record Chronicle | News for Denton County, Texas | Local News:

"Ragsdale heard his dog screech, and looked up to see a big cat moving across a vacant lot.

"In two bounds, he was gone," Ragsdale said, who then ran back to the house to grab a flashlight and his pistol.

He tried to track the animal through a creek bed until he came upon a pile of bones. He could see the bones from another dog's foot in the pile and realized his pursuit wasn't such a good idea. He returned home only with his dog's collar.

Wildlife experts say either a bobcat or a mountain lion could have easily made off with the dog. Considering this summer's extraordinary drought, Ragsdale says he's concerned that the big cat may not have been the former, but the latter."

Published on September 03, 2011 09:17

September 2, 2011

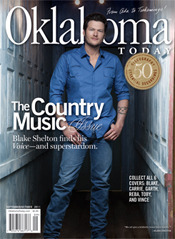

Grice Meets Garth Brooks. . . Almost

The country music issue of Oklahoma Today seems like an improbable place to find your favorite nature writer, but there I am, yammering on about the time I didn't encounter my college contemporary Garth Brooks at Willie's Saloon. What I did encounter that life-changing night was the great blues man Flash Terry. Check it out--it's the September/October issue.

Published on September 02, 2011 10:26

September 1, 2011

Alligator Attacks Elderly Woman

Alligator attack: Alligator attacks elderly woman walking near canal - South Florida Sun-Sentinel.com:

"Officials say the woman, who lost part of her leg in the attack, was airlifted to a Fort Myers trauma center.

FWC says a trapper was sent to the area to find the alligator. If found, the reptile will be cut open in an attempt to retrieve and reattach the leg."

"Officials say the woman, who lost part of her leg in the attack, was airlifted to a Fort Myers trauma center.

FWC says a trapper was sent to the area to find the alligator. If found, the reptile will be cut open in an attempt to retrieve and reattach the leg."

Published on September 01, 2011 21:40

Fly Amanita

They say you can leaves pieces of this woodland fungus sopping in milk to kill flies. The flies drink the milk, stagger like Saturday night sailors, and drown.

Photography by D'Arcy Allison-Teasley

Published on September 01, 2011 10:41

August 31, 2011

Rust: The Conclusion

A moody morning after rain. The rusts had poured forth their tentacles again, but after a few hours the tentacles had withered to brown scraps. My oldest son and I decided to retrieve one of them for study. He held a slender branch taut while I cut. The shears met in the wet wood with a squeak and a snap; the branch sprang upward, leaving its severed extremity in my son's hands. He plucked the rust off it avidly.

We watered it in a jar and it revived. Overnight, new tendrils of orange slime pushed their way out through the colandered sphere. It did not need rain, then; any drenching would do.

The next stage of our inquiry was a white plastic cup. We had learned that the rust spreads orange spores while it's active. Looking over its gelatinous tentacles, I had no doubt our specimen was alive, but we made the experiment anyway. Into the little white cup it went with a fresh supply of water. In the morning, the water showed orange against the cup—its spores coloring the water like a weak dose of Tang.

For a few days, my sons were always bringing in bigger, juicier specimens of the rust, poking them with sticks, marveling at them. Then their interest dwindled, and I'd find week-old jars of the things on shelves and window sills, the tentacles half dissolved in the water, retaining only their color.

*

I always suspected we were cousins. The fungi don't move the way we do, but some of them, the most visible ones, grow so fast it seems a sign of animal life: the mushroom big as a human fist found on your lawn the day after a rain, for example. I have a vivid childhood memory: something smooth and white nesting in the grass, the size and shape of a chicken egg, hardboiled and peeled. It was not an egg, however: my dog evinced no interest in it. Something about it made me reticent to touch it. It had no smell, but something about it reminded me of dog feces, or perhaps merely the Platonic form of disgust. The weird notion that it was an eyeball crossed my mind, and I went so far as to turn it over with a twig, looking for an iris. It was this operation that revealed its true nature to me, for it tore open under the stick and revealed, first, the stringy origami I associated with the insides of some mushrooms. The other thing this tearing revealed was the smell, which had hitherto been undetectable, the smell of rotten flesh.

Or maybe their overnight appearances simply seem like a sinister kind of magic. Toadstools, elves.

*

It is not only the plants that live in symbiosis with fungi. We animals do it, too. We do not like to think of it, because we have for so long conceived of microbes as unclean things, as invaders. But of course we have always been symbionts, dependent on the microbes in our guts to digest our food. We have colonies of fungus inside us as well. A so-called yeast infection is really an imbalance. It is not a problem that the yeasts are in the human body—they always are. It's a problem that their numbers have, because of some teetering of the pH level, exceeded their usual bounds. It is a natural thing to share our bodies with them, and with all manner of other organisms. As a tree is not simply a tree, we are not simply what we think we are.

Which is not to exonerate them all. Plenty of fungi are pure parasites, and these have invaded almost every kind of life. There are specialized fungal parasites of single-celled diatoms and even of other fungi. And some of these cause serious harm. The rust on my cedar tree was bad for it; it must have been even worse for the apple trees in the neighborhood, for the leaves of the apple are slowly pierced through by the rust, until spore-shooting orange masts sprout from their undersides. The fruit of the apple, too, may be ruined, its hide marred by soft brown patches.

So, too, with the human form. There are fungi to make the feet and the testicles itch, fungi to discolor and deform the fingernails. And there are neighborly fungi content to live within us unobserved, but which will blossom, in the case of a ruined immune system, into devouring sores, inside and out. It is a common enough way for people with AIDS to die.

*

Two years have passed since the last time our cedar was dazzling in its orange jewelry. The next year we waited in vain for another blooming of that odd fungal life. We had trimmed them off where we could reach, hoping to save the tree, but it wasn't our earthbound efforts that drove them away. We could still see dozens of them higher up, dry and drab, refusing to bloom.

Our tree grows shaggier year by year, more patched with vanilla and auburn. Within the greenery that remains I can reach dozens of lifeless branches. A good yank is sure to be rewarded with the crack of dead wood, dry enough to burn. The whole tree is ugly now, truth to tell. It reminds me of nothing so much as the shaggy head of a neglected old man.

Not that I neglect it. I prune; I am doing what I can to save its life. But it is dying, I'm sure of it. When we walk beneath it, mosquitoes and blackflies come for us by the swarm.

Next: An Intoxicating Fungus.

This story originally appeared in Discover.

Published on August 31, 2011 09:47

August 30, 2011

Cougar Injures Toddler

Toddler mauled by cougar in Vancouver Island park; animal being tracked - Winnipeg Free Press:

"UCLUELET, B.C. - A cougar attack that injured an 18-month-old boy in a British Columbia park was stopped after the child's grandfather and a family friend scared off the animal, which also lunged towards the boy's four-year-old sister, parks officials said Tuesday.

The boy was listed in serious condition in Vancouver's Children's Hospital after he was attacked Monday evening in the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The attack happened a popular day-use spot at Kennedy Lake, east of Ucluelet."

"UCLUELET, B.C. - A cougar attack that injured an 18-month-old boy in a British Columbia park was stopped after the child's grandfather and a family friend scared off the animal, which also lunged towards the boy's four-year-old sister, parks officials said Tuesday.

The boy was listed in serious condition in Vancouver's Children's Hospital after he was attacked Monday evening in the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The attack happened a popular day-use spot at Kennedy Lake, east of Ucluelet."

Published on August 30, 2011 23:44

Rust, Part 1 of 2

The Stoics asserted that human beings sprang forth from the soil of hill and plain like sprouting mushrooms.

Francesco Redi

Our move brought me over a lift-bridge in the middle of a rainy night. Tracy had taken the place and set up housekeeping, and now she was showing me the way home. Our sons were in the back, one talking, the other sleeping. The road curved into the moist dark. "I'll bet you're wondering what I got you into," Tracy said.

But in the morning the place was sunshine and the chatter of finches. We were to live in a village in the upper Midwest. The front of our place was a busy and badly paved road; the back was a straggling wood. Winter nights, you'd be able to see all the way through the naked forest to the houses on the other side. But for now it was spring and I had the illusion of a wilderness.

The Eastern red cedar tree in our back yard looked bad—shaggy, wasted, a dandruff of gray decline mixed in with the healthier bluish-green needles. We saw the cause: little spiky galls hanging here and there like drab Christmas ornaments. Each of these ornaments was smaller than a golf ball and seemingly made of wood, which might make you think it was some healthy part of the tree. I picked one off. Each little spike was a spout: a hole surrounded by a sharp woody projection. The ball resisted pressure only as much as a fruit might. Carrying it to the cement walk, I crushed it under my heel. It wasn't difficult. Inside, the thing was pulpy and fibrous, its strands of vegetable matter radiating from a tight core. Its wet texture was like that of the new wood you can find under a tree's bark.

I knew this as cedar apple rust, a parasite with a provocative life cycle. On the leaves and fruit of apple trees, this fungus manifests itself as leathery patches of discoloration. On red cedar trees, it takes the form of these woody galls. The apple and cedar forms of this parasite are different stages of a single life cycle which involves both sexual and asexual spores.

To look at it, though, I wouldn't have recognized this sphere as alien to the tree, made as it was of the tree's own tissues. The tree itself makes the sphere, acting on instructions from the fungus, like an animal body producing a tumorous mass at the command of rogue cells. My sons gathered a few and smashed them with a tenderizing mallet to examine their insides.

Rain revealed more. It rained for two or three days, a steady soak that had my sons whooping barefoot on the lawn. One day they were all excitement: "The parasite opened up!"

. . . a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Indeed. All over the fifty-foot tree, the galls had effloresced. Through each spiky spout, a vivid orange tentacle projected. It seemed as if the tree had collided with a swarm of sea anemones.

I bent a bough down so the boys could see. My older son poked at one gall and proclaimed it slimy. I tried its texture myself: wet gummy worms. Our gentlest touches marred them. I almost expected them to recoil.

*

It used to be said that a fungus was a sort of defective or degenerate plant, one that lacked chlorophyll and so could not make its own food. It was thus reduced to feeding off the work of others—grubbing in the soil to devour dead animals, fallen leaves, and damp wood.

Biologists know better now, partly because of advances in genetics. In the last few years, DNA sequencing has revealed strong evidence for all sorts of things we hardly could have suspected—that whales belong among the even-toed hoofed mammals, that dinosaurs and birds are more closely related to crocodiles than turtles are. The method behind this is to look for similar strings of DNA, then analyze them statistically. All life on earth comes from a common stock; the more dissimilar two life forms are genetically, the longer it's been since they diverged. By applying sophisticated mathematical models, geneticists can estimate how long it takes for certain kinds of differences to arise. By comparing these numbers, they can deduce how closely related different kinds of living things are.

But this re-evaluation of relationships goes deeper than the shifting of animals among orders. Our vision of life at the most basic levels has altered too; the kingdoms, the very fundaments of Linnaean biology, have had to be shifted about. The fungi comprise their own kingdom now. We understand, better than we did at least, what they are. Certain organisms we had called fungi because they were slimy and repulsive and because we didn't know where else to put them—the slime molds, for example—have been exiled from the kingdom. That is not too hard to take, because few of us encounter slime molds with any regularity.

What's harder to take is that fungi turn out to be our kinsmen. They are not plants at all; they are closest to the animals—to us.

*

We usually think of fungus as an unhealthy thing, a sign of disease. That's a slander, for parasitism is only one of the possibilities of fungi.

In the woods behind my house I find uncountable lichens. These are, as every high school student learns, symbiotes, a fungus paired with an alga or a similar lifeform. They are the surface I touch when I lay my hand on a fallen tree; they are the first flaky layer my handsaw bites through when I gather dead wood. When my sons climb to prospect for higher views, half their footholds are ledges of lichen or simple fungus.

I called them uncountable. This is only partly because they are numerous. The other reason I can't quantify them is that they lack integrity. The whole leeward side of a certain box elder tree is crusted with green: where does one lichen end and another begin?

Fungi are often colonial, rather than singular. A million fungal filaments in a patch of soil may be in communication of a sort, all of them sending strands toward a food source when one detects it. There is, of course, no brain, no central command, merely a shared purpose. If we consider one such aggregation a single individual, then the largest life forms we know are fungal: stretching for miles within the soil, their mass rivaling that of the blue whales or perhaps even the redwoods.

If the individuality we tend to think of as fundamental is lacking in the fungi, then so are the species boundaries. Lichens are only one kind of symbiosis; the fungi have many. One style, for example, is the mycorrhiza, a combination of fungi with the roots of a plant. The fungi reach where the plant cannot, bringing in minerals the plant needs; the plant shares the food it makes from light and water. Though most people are perhaps not familiar with this arrangement, it is the basis of life as we know it. At least 80% of plants cohabit in such a manner—some estimates go as high as 90. The boundaries are not exactly where we are accustomed to draw them, because, practically speaking, the average tree or weed or grass is not merely a plant, but a combination of plant and fungus.

It is not easy to grasp this, or to see it without benefit of excavation, dissection, and microscopy. But the signs are visible, if you look. Sometimes in wet weather I find an arc of mushrooms in my front yard. It is this arcing distribution that reveals hidden relationships, for the focus of the arc is a maple tree. The mushrooms are the genitals of fungi intimate with the tree. It is possible to trace its thicker roots, barely concealed in the dirt, to aggregations of mushrooms.

To be continued.

This story originally appeared in Discover.

Published on August 30, 2011 16:45

August 29, 2011

Leopard Hurts Hunters

In South Africa, a two hunting guides were injured by a wounded leopard. I believe this sort of guide is what used to be called a "white hunter"--a professional who guides amateurs to get their trophy kills as safely as possible. According to Peter Capstick, following up a wounded leopard is just about the most dangerous gig on the planet.

Leopard attacks on game farm: News24: South Africa: News:

"A foreign trophy hunter had shot and injured a leopard late on Saturday afternoon, and a tracking party set out to find the animal, said ER24 spokesperson Andre Visser.

Instead, the injured leopard stalked and attacked the group, at 09:00 on Sunday.

The leopard darted for the trophy hunter, but the male guide, believed to be in his mid thirties, stepped in front of his client.

The leopard mauled the man's left shoulder, arm, and abdomen, while his wife received multiple lacerations to her arm."

Leopard attacks on game farm: News24: South Africa: News:

"A foreign trophy hunter had shot and injured a leopard late on Saturday afternoon, and a tracking party set out to find the animal, said ER24 spokesperson Andre Visser.

Instead, the injured leopard stalked and attacked the group, at 09:00 on Sunday.

The leopard darted for the trophy hunter, but the male guide, believed to be in his mid thirties, stepped in front of his client.

The leopard mauled the man's left shoulder, arm, and abdomen, while his wife received multiple lacerations to her arm."

Published on August 29, 2011 22:39

Confirmed: Grizzly Killed Hiker in Yellowstone

Follow-up to the news item linked here this morning. Yellowstone officials already suspected, from evidence at the scene, that the Michigan man whose remains were found on a Yellowstone trail died from a grizzly attack. The autopsy results have now confirmed that suspicion.

Predictably, some papers are treating this latest killing as part of a nature-strikes-back trend, even though grizzlies remain a highly improbable way to die. (But, as documented here over the summer, black bears are another matter. I'll be writing about that in more detail in an upcoming issue of Men's Journal.)

Yellowstone: Hiker killed by bear; Identity released | KBZK.com | Z7 | Bozeman, Montana:

"Rangers discovered signs of grizzly bear activity at the scene Friday afternoon, including bear tracks and scat. An autopsy was conducted Sunday afternoon and determined that Wallace died as a result of a bear attack, the park said. Park rangers, wildlife biologists, and park managers are continuing to investigate."

Photo by Wayne T. Allison

Published on August 29, 2011 13:12

A Mystery Resolved in Rust

In a summer when orange funk rained from Alaska skies and poisonous seaweed littered the beaches of Brittany with dead boars, when a Texas lake turned blood red and a holy man declared we were living in the end times, the wounded world seemed to be telling us something we'd rather not hear. Be that as it may, scientists now have some answers in the mystery of the Alaskan funk.

Orange goo on Alaska shore was fungal spores - US news - msnbc.com:

"Further tests with more advanced equipment showed the substance is consistent with spores from fungi that create 'rust,' a plant disease that accounts for the color, said officials with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The gunk appeared Aug. 3 at the edge of Kivalina, an Inupiat Eskimo community at the tip of a barrier reef on Alaska's northwest coast."

There are many kinds of rust, one of which is an old friend of mine. Indulge me and tomorrow I'll tell the story.

Published on August 29, 2011 09:11