Gordon Grice's Blog, page 79

September 30, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 3

Go to the beginning of this story

The rain has turned to a slushy snow by the time I get to the Museum of the Cherokee Strip. A man behind the counter has silver-and-gold hair and wears wire-frame glasses and a red Izod cardigan. He is, I soon discover, a published Egyptologist, which seems an odd specialty for somebody who works in a museum in Enid, Oklahoma. He begins a standard spiel--a gallery to your right, our reconstructed turn-of-the-century town through that door and to your--but stops when he sees my notebook come out from under my rain coat.

"Are you researching something in particular?" he says. I think I detect a hint of trepidation in his voice.

"I'm interested in the mummy of John Wilkes--" I begin. He silences me with a bored nod and a grim smile. I've come to know the look well since my arrival in Enid.

He turns to a colleague at the other end of the counter. "Steve, he's another of the David E. Georges."

Steve Dortch, the museum's curator, is dressed in jeans and a flannel shirt. "I'll be glad to argue David E. George with you," he says with a West Texas accent. "Which side you want me to take?"

I insist I want his true opinion, so he decides to argue both sides of the case. He begins with the factors in favor of George's authenticity, counting them off on the fingers of his right hand. "He looked like Booth. He was about the right age. He'd had a broken leg; Booth broke his leg when he jumped to the stage and got his spur tangled in the flag. David E. George had a flattened-out finger; so did Booth. George was a bad Shakespearean actor; so was Booth.

"On the other hand!" Dortch says. After a dramatic pause, he begins to count the reasons for George's fraudulence on his left hand. "One, anybody could have a broken leg, or limp and say he had a broken leg. Two, what would a bunch of uneducated rednecks know about Shakespeare? He could have been faking that."

"But what do you think?" I interrupt.

"I think he said it to get people to buy him drinks."

The first man, whose name is Glen McIntyre, chips in. "We don't want to throw water on your project, but. . . ." According to McIntyre's theory, George, who was an drug addict and perhaps a schizophrenic, might have believed his own claim. McIntyre adds a theory an acquaintance of his came up with, which is that George had made his living passing himself off as Booth at opera houses and theaters on the frontier before Booth became a notorious assassin.

McIntyre tells about the local David E. George Society, where the only requirement for membership is to have an opinion about George's authenticity and be willing to argue the point.

"That society is more or less a joke," Dortch says.

"You guys seem kind of impatient with the George story," I observe.

"The trouble with people in Enid," Dortch says, "is they want a tourist attraction, but they don't want to charge admission. Enid has so many historically interesting personalities, it's a shame that our claim to fame is some dead old drunken fraud." He lists Henry Cessna of airplane fame, the inventor of the Geronimo car, and an astronaut whose name he can't immediately recall. Then he tells about Dolly Douthitt.

Mrs. Douthitt was a pioneer who claimed a homestead in the county in 1893, the year Enid came into existence. Her first historically noteworthy act was in 1904, the year after David George's suicide. Having surprised her husband in the barn during a romantic interlude with a maid, Mrs. Douthitt shot him on the spot. Before dying of the wound, Mr. Douthitt made out a will leaving his wife a share of his estate on the condition she never remarry. His will also asked that she not be prosecuted for his murder--a dying wish that was granted.

Oh tiger's heart, wrapped in a womans hide!

William Shakespeare

Mrs. Douthitt was only 31, and though she abided by her dead husband's injunction against remarriage, she took a lover. This man apparently did something to displease his paramour, for one morning as he lay sleeping, she castrated him with a straight razor. The man ran from the house and traveled on foot to the hospital. Along the way he crossed a creek bottom and paused to say good morning to the paper boy. Despite losing a long trail's worth of blood, he survived. Mrs. Douthitt again escaped prosecution.

But her difficulties weren't over. One of her daughters went insane. Another, who had the memorable name of Mona Loma Thelma Pearl Douthitt Hourahan, became despondent over her husband's supposed infidelities. She had to try six drugstores before she found one that would sell her cyanide--perhaps the druggists remembered the case of David E. George. When she did score some cyanide, she used it to dispatch her husband and herself. "Life and men are such disappointments," her suicide note explained.

Two years after her daughter's suicide, Dolly Douthitt, having run into financial trouble, found herself in court to answer several lawsuits. She acted as her own attorney, and her defense ran like this: "You fiends, you sons of bitches, I will get you all!" So saying, she produced a pistol and began shooting. Her first bullet lodged in the empty jury box. Her second was apparently aimed at the groin of opposing counsel. It went slightly high, puncturing the man's intestines thirteen times. He fell to the floor with a law book in his hands. This he handed to a fellow attorney, asking him to return it to the mutual acquaintance who had lent it.

Another attorney ran out of the courtroom and into the street, where he is alleged to have tripped and rolled to the far curb. Two more attorneys took shelter under a table. Mrs. Douthitt's third shot was meant for the judge, but it only marred the sleeve of his tweed coat. Her fourth effort, a clean miss, was directed at yet another attorney, who tossed a file full of papers into Mrs. Douthitt's face. The judge, having apparently tired of the matter, descended from his bench, seized Mrs. Douthitt from behind, and choked her until her tongue protruded and her grip on the gun loosened. She was sent to a mental institution.

"So if you want criminals," Dortch concludes, "David E. George is not even the best murderer Enid has to offer."

Published on September 30, 2011 09:45

September 29, 2011

Abraham Lincoln's Autopsy

The Nelaton probe used to find the bullet in Lincoln's brain; fragments of bone;

The Nelaton probe used to find the bullet in Lincoln's brain; fragments of bone; strands of hair; the bullet; the bloody sleeve of Dr. Curtis.

An extract from the case history of Abraham Lincoln after he was shot by John Wilkes Booth:

CASE.-A. L-----, aged 56 years, was shot in the head, at Washington, on the evening of April 14th, 1865, by a large round ball, from a Derringer pistol, in the hands of an assassin. Dr. Charles A. Leale being close at hand, went instantly to the wounded man, whom he found "in a profoundly comatose condition,"… the breathing "exceedingly stertorous." No pulsation was perceptible at the right wrist. When the head was examined, "I passed my fingers over a large firm clot of blood,…[that] I easily removed, and passed the little finger of my left hand through the perfectly smooth opening made by the ball, and found that it had entered the encephalon. As soon as I removed my finger, a slight oozing of blood followed, and his breathing became more regular and less stertorous." After the administration of a small quantity of brandy and water,…the patient was removed to a neighboring house... His clothing was removed, and he was placed in bed. His extremities were cold. He was covered with warmed blankets, and bottles of hot water were applied to the lower extremities. It was now about eleven o'clock at night, the wound having been inflicted about half past ten. His family physician, Dr. Robert H. Stone, and Surgeon General Barnes, and Assistant Surgeon General Crane, arrived presently;... The Surgeon General accordingly kept the external wound open by means of a silver probe, until, a Nelaton's probe being brought, he made an exploration of the course of the ball. A splinter obstructed the track at the depth of about two and a half inches. An inch and a half further on the bulb came in contact with a foreign body, which proved to be the disc from the occipital forced out by the ball; passing beyond this the ball was detected, at a distance of over six inches from the entrance wound….it was decided that no attempt should be made to remove it or the foreign bodies, further than to keep the opening free from coagula, which, when allowed to form and remain for a very short time, would produce signs of increased compression, the breathing becoming profoundly stertorous and intermittent, and the pulse more feeble and irregular. The protracted death-struggle ceased at twenty minutes past seven o'clock on the morning of April 15th, 1865.

One of the doctors who performed an autopsy on the body later wrote to his mother:

Dr. Woodward and I proceeded to open the head and remove the brain down to the track of the ball. The latter had entered a little to the left of the median line at the back of the head, had passed almost directly forwards through the center of the brain and lodged. Not finding it readily, we proceeded to remove the entire brain, when, as I was lifting the latter from the cavity of the skull, suddenly the bullet dropped out through my fingers and fell, breaking the solemn silence of the room with its clatter, into an empty basin that was standing beneath. There it lay upon the white china, a little black mass no bigger than the end of my finger—dull, motionless and harmless, yet the cause of such mighty changes in the world's history as we may perhaps never realize.

The official autopsy report by Dr. Woodward includes the fatal injuries:

The eyelids and surrounding parts of the face were greatly ecchymosed and the eyes somewhat protuberant from effusion of blood into the orbits.

There was a gunshot wound of the head around which the scalp was greatly thickened by hemorrhage into its tissues. The ball entered through the occipital bone about one inch to the left of the median line and just above the left lateral sinus, which it opened. It then penetrated the dura mater, passed through the left posterior lobe of the cerebrum, entered the left lateral ventricle and lodged in the white matter of the cerebrum just above the anterior portion of the left corpus striatum, where it was found.

The wounds in the occipital bone was quite smooth, circular in shape, with beveled edges. The opening through the internal table being larger than that through the external table. The track of the ball was full of clotted blood and contained several little fragments of bone with a small piece of the ball near its external orifice. The brain around the track was pultaceous and livid from capillary hemorrhage into its substance. The ventricles of the brain were full of clotted blood. A thick clot beneath the dura mater coated the right cerebral lobe.

There was a smaller clot under the dura mater of the left side. But little blood was found at the base of the brain. Both the orbital plates of the frontal bone were fractured and the fragments pushed upwards towards the brain. The dura mater over these fractures was uninjured. The orbits were gorged with blood.

Next: Continuing the mystery of The George Mummy

Published on September 29, 2011 09:12

September 28, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 2

Go to the beginning of this story.

Thou cam'st on earth to make the earth my Hell.

A grievous burden was thy Birth to me,

Tetchy and wayward was thy Infancy.

Thy School-days frightful, desp'rate, wild, and furious,

Thy prime of Manhood daring, bold, and venturous:

Thy Age confirmed, proud, subtle, sly, and bloody,

More mild, but yet more harmful; Kind in hatred.

Bloody thou art, bloody will be thy end:

Shame serves thy life, and doth thy death attend.

William Shakespeare

John Wilkes Booth may have been the most popular actor in America in 1865. He came from a family of actors, but at age 26 he had already surpassed his famous father and brother in popularity. One newspaper called him "the most handsome man on the American stage." He received a hundred love letters a week. His annual income was about $20,000, fifty times that of an average working man. He was sexy and charismatic, and his reviewers usually alluded to his "flashing black eyes." His signature role was the demonic Richard III.

Richard:

Why, I can smile, and murder whiles I smile,

And cry 'Content' to that which grieves my heart,

And wet my cheeks with artificial tears,

And frame my face to all occasions.

I can add colours to the chameleon,

Change shapes with Proteus for advantages,

And set the murderous Machiavel to school.

William Shakespeare

Offstage, Booth was a romantic who gave himself to torrid affairs, extravagant drinking, and losing causes. As a boy in military school, he had taken part in an armed insurrection against his cruel masters--and was successful in having the school's draconian policies softened. Although he spent the Civil War years in the North, he loudly supported the Southern cause. When Abraham Lincoln, an avid theater-goer, saw Booth in a play and asked to meet with him, Booth refused; he hated what Lincoln stood for. Preaching the Southern cause in the North was risky, but Booth's popularity and family connections protected him. Some if his colleagues had the impression his support for the South was more pose than reality. "He was so infected and unbalanced by his profession that the world seemed to him to be a stage on which men and women were acting, living, their parts," wrote his contemporary Joel Chandler Harris.

Sometime during the War, Booth became involved in a conspiracy. At first, the idea was to kidnap President Lincoln and several other top government officials and use them to force an exchange, freeing Southern prisoners of war. In the waning days of the War, this plan seemed the only way to reverse the South's declining fortunes. But the plan fell apart. In the end, Booth decided the only way to salvage things was to kill Lincoln instead.

from "The Death of Abraham Lincoln"

Walt Whitman

1879

I remember where I was stopping at the time, the season being advanced, there were many lilacs in full bloom. By one of those caprices that enter and give tinge to events without being at all a part of them, I find myself always reminded of the great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms. It never fails.

The popular afternoon paper of Washington, the little "Evening Star," had spatter'd all over its third page, divided among the advertisements in a sensational manner, in a hundred different places, "The President and his Lady will be at the Theatre this evening…." (Lincoln was fond of the theatre. I have myself seen him there several times. I remember thinking how funny it was that he, in some respects the leading actor in the stormiest drama known to real history's stage through centuries, should sit there and be so completely interested and absorb'd in those human jack-straws, moving about with their silly little gestures, foreign spirit, and flatulent text.)

On this occasion the theatre was crowded, many ladies in rich and gay costumes, officers in their uniforms, many well-known citizens, young folks, the usual clusters of gas-lights, the usual magnetism of so many people, cheerful, with perfumes, music of violins and flutes—(and over all, and saturating all, that vast, vague wonder, Victory, the nation's victory, the triumph of the Union, filling the air, the thought, the sense, with exhilaration more than all music and perfumes.)

The President came betimes, and, with his wife, witness'd the play from the large stage-boxes of the second tier, two thrown into one, and profusely drap'd with the national flag. The acts and scenes of the piece—one of those singularly written compositions which have at least the merit of giving entire relief to an audience engaged in mental action or business excitements and cares during the day, as it makes not the slightest call on either the moral, emotional, esthetic, or spiritual nature—a piece, ("Our American Cousin,") in which, among other characters, so call'd, a Yankee, certainly such a one as was never seen, or the least like it ever seen, in North America, is introduced in England, with a varied fol-de-rol of talk, plot, scenery, and such phantasmagoria as goes to make up a modern popular drama—had progress'd through perhaps a couple of its acts, when in the midst of this comedy, or non-such, or whatever it is to be call'd, and to offset it, or finish it out, as if in Nature's and the great Muse's mockery of those poor mimes, came interpolated that scene, not really or exactly to be described at all, (for on the many hundreds who were there it seems to this hour to have left a passing blur, a dream, a blotch)—and yet partially to be described as I now proceed to give it. There is a scene in the play representing a modern parlor in which two unprecedented English ladies are inform'd by the impossible Yankee that he is not a man of fortune, and therefore undesirable for marriage-catching purposes; after which, the comments being finish'd, the dramatic trio make exit, leaving the stage clear for a moment. At this period came the murder of Abraham Lincoln.

As Lincoln watched a play that evening, Booth walked into Ford's Theater, where he had worked as an actor many times before, and where his presence aroused no suspicion. Lincoln's bodyguard stepped away from his post to watch the play. Booth slipped into the private box where Lincoln sat. He shot Lincoln behind the ear, the bullet sluicing diagonally through the President's brain before lodging. Booth tossed his derringer aside and drew a knife, which he used to wound the soldier sitting beside Lincoln.

Then he leapt from the box to the stage fourteen feet below. As he leapt, the spur of his boot caught in the American flag that draped the front of the box. He crashed to the stage, breaking his leg. The sound of his gunshot had been swallowed in the audience's chatter. When Booth made his clumsy appearance on stage, every person in the theater recognized him. There was applause, mixed with murmurs of confusion. Booth shouted, "Sic semper tyrannus!" -- "such always to tyrants!" -- and fled.

Great as all its manifold train, circling round it, and stretching into the future for many a century, in the politics, history, art, &c., of the New World, in point of fact the main thing, the actual murder, transpired with the quiet and simplicity of any commonest occurrence—the bursting of a bud or pod in the growth of vegetation, for instance. Through the general hum following the stage pause, with the change of positions, came the muffled sound of a pistol-shot, which not one-hundredth part of the audience heard at the time—and yet a moment's hush—somehow, surely, a vague startled thrill—and then, through the ornamented, draperied, starr'd and striped space-way of the President's box, a sudden figure, a man, raises himself with hands and feet, stands a moment on the railing, leaps below to the stage, (a distance of perhaps fourteen or fifteen feet,) falls out of position, catching his boot-heel in the copious drapery, (the American flag,) falls on one knee, quickly recovers himself, rises as if nothing had happen'd, (he really sprains his ankle, but unfelt then)—and so the figure, Booth, the murderer, dress'd in plain black broadcloth, bare-headed, with full, glossy, raven hair, and his eyes like some mad animal's flashing with light and resolution, yet with a certain strange calmness, holds aloft in one hand a large knife—walks along not much back from the footlights—turns fully toward the audience his face of statuesque beauty, lit by those basilisk eyes, flashing with desperation, perhaps insanity—launches out in a firm and steady voice the words Sic semper tyrannis—and then walks with neither slow nor very rapid pace diagonally across to the back of the stage, and disappears. (Had not all this terrible scene—making the mimic ones preposterous—had it not all been rehears'd, in blank, by Booth, beforehand?)

A moment's hush—a scream—the cry of murder—Mrs. Lincoln leaning out of the box, with ashy cheeks and lips, with involuntary cry, pointing to the retreating figure, He has kill'd the President. And still a moment's strange, incredulous suspense—and then the deluge!—then that mixture of horror, noises, uncertainty—(the sound, somewhere back, of a horse's hoofs clattering with speed)—the people burst through chairs and railings, and break them up—there is inextricable confusion and terror—women faint—quite feeble persons fall, and are trampl'd on—many cries of agony are heard—the broad stage suddenly fills to suffocation with a dense and motley crowd, like some horrible carnival—the audience rush generally upon it, at least the strong men do—the actors and actresses are all there in their play-costumes and painted faces, with mortal fright showing through the rouge—the screams and calls, confused talk—redoubled, trebled—two or three manage to pass up water from the stage to the President's box—others try to clamber up—&c., &c.

In the midst of all this, the soldiers of the President's guard, with others, suddenly drawn to the scene, burst in—(some two hundred altogether)—they storm the house, through all the tiers, especially the upper ones, inflam'd with fury, literally charging the audience with fix'd bayonets, muskets and pistols, snouting Clear out! clear out! you sons of——…. Such the wild scene, or a suggestion of it rather, inside the play-house that night.

Outside, too, in the atmosphere of shock and craze, crowds of people, fill'd with frenzy, ready to seize any outlet for it, come near committing murder several times on innocent individuals. One such case was especially exciting. The infuriated crowd, through some chance, got started against one man, either for words he utter'd, or perhaps without any cause at all, and were proceeding at once to actually hang him on a neighboring lamp-post, when he was rescued by a few heroic policemen, who placed him in their midst, and fought their way slowly and amid great peril toward the station house. It was a fitting episode of the whole affair. The crowd rushing and eddying to and fro—the night, the yells, the pale faces, many frighten'd people trying in vain to extricate themselves—the attack'd man, not yet freed from the jaws of death, looking like a corpse—the silent, resolute, half-dozen policemen, with no weapons but their little clubs, yet stern and steady through all those eddying swarms—made a fitting side-scene to the grand tragedy of the murder. They gain'd the station house with the protected man, whom they placed in security for the night, and discharged him in the morning.

Until the moment of his death, Lincoln was the most unpopular president in American history, reviled in the South as a dictator and lampooned in the North for his intention to preserve the defeated South. Almost overnight, the martyred Lincoln, the first American President to be assassinated, became a symbol of integrity, a sort of political saint. At the same time, Booth, the country's most popular actor, suddenly became its most notorious criminal. Whole families of Booths changed their surnames; fans ripped his photo from their scrapbooks.

The government launched an investigation. Eight people were eventually convicted in the conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln and other Northern leaders; four were executed, including Mary Surratt, the first woman legally executed in the United States. Even conservative historians soon came to believe the conspiracy was broader, and perhaps included government officials who were never indicted; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton is often mentioned. Booth had escaped, and the government immediately arranged a reward for his capture. Twelve days after the assassination, soldiers tracked Booth to a tobacco shed on the Garrett farm in Virginia. Booth refused to surrender. When he raised his gun to fire on soldiers, a sergeant named Boston Corbett dropped him with a single shot which took him in the back of the neck--two inches from the location of Lincoln's fatal wound. He was buried under the stone floor of a military prison. Four years later, his family managed to have his body exhumed and transferred to the family plot in Baltimore's Greenmount Cemetery.

Richard:

For many lives stand between me and home:

And I,--like one lost in a thorny wood,

That rends the thorns and is rent with the thorns,

Seeking a way and straying from the way;

Not knowing how to find the open air,

But toiling desperately to find it out,--

Torment myself to catch the English crown.

William Shakespeare

That's the official ending of the story. Alternate stories of Booth's fate cropped up almost immediately, partly because of suspicious loose ends in the Lincoln assassination—pages missing from Booth's diary, Booth's calling card left for Vice-President Andrew Johnson the day of the assassination, General Grant mysteriously canceling his plan to see the play with Lincoln that night. Dr. Frederick May, who had once cut a tumor from Booth's neck, remarked on first seeing the official corpse that it looked nothing like Booth. But he changed his mind when he saw the familiar surgical scar. The central premise of the alternate stories is that Booth escaped while another man was killed in his place, and highly-placed conspirators covered up the switch.

Published on September 28, 2011 09:20

September 27, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 1

This piece originally appeared, in a much shorter form, in Oklahoma Today. As with "Slice," I was sorry to have to leave out so much weird and interesting material to fit it into the magazine.

The George Mummy

My ashes, as the phoenix, may bring forth

A bird that will revenge upon you all.

William Shakespeare

A cold rain is falling in Enid, Oklahoma. Inside Garfield Furniture, customers bustle, their shoes squeaking on the burnished wood floor. I seem to be the only one waiting to see the Death Room. When there's a lull in the trade, the proprietor greets me and guides me up a narrow staircase.

A century ago the furniture store was a hotel, and on the second floor its honeycomb of tiny rooms is mostly intact, and mostly crammed with excess inventory. He takes me into the Death Room, the walls of which are covered with tatters of turn-of-the-century wallpaper. In this narrow cell--maybe six feet wide, with walls reaching far short of the ceiling--the furniture is a century old, but set up as if for living--an iron bedstead with a thin mattress, a wash stand and basin, a table and hard-backed chair.

An array of photocopied documents covers the bed: insurance maps showing the location of the town's businesses ninety-six years ago, a handwritten will, newspaper clippings, and a photograph of a mummified corpse sitting in a chair, eyes wide, with a newspaper spread in its lap.

The proprietor tells the story.

*

In 1903, Oklahoma was not yet a state. The town of Enid, a city on the plains of north central Oklahoma which now has a population of 45,000, was then a decade old, having formed literally overnight in a land run. It was an agglomeration of red cedar and pine buildings leaning on each other's shoulders, the land just beginning to be marked out from the surrounding prairie by lawns and hedges. The Old West may have been dying out, but in the Oklahoma Territory there were still long-riding outlaws with names like Rattlesnake Jim and Dynamite Dick. The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Marquis James, who was a boy in Enid at the time, remembered being brought to the jail to shake hands with a dying killer named Dick Yeager.

James described the settlers of this " ancestorless country" as "people who for one reason or another had lost out, been run out or weren't doing well enough to suit themselves in the places they came from"--debtors, wanted men, elopers, men escaping paternity suits, itinerant printers forced out of the cities by the coming of the linotype, laborers rushing from town to town with the building booms. It was bad manners to ask about a man's past here. Most of the transitory populace lived in hotel rooms like the one I'm standing in, rooms more like horse stalls than human habitations.

Among the apparently rootless men of Enid in January 1903 was a sixtyish man who had been in town for only a few weeks. He had registered at the Grand Avenue Hotel under the name David E. George. In his three weeks in Enid, he had already run up tabs at several bars and hocked his watch for whiskey. His most successful gambit for getting drinks without cash was to recite poetry and passages of Shakespeare. ("It may have sounded like Shakespeare to the men in the saloons who heard it," one resident said decades later. "But we didn't know much of Shakespeare in Oklahoma Territory in those days.")

Richard:

My eye's too quick, my heart o'erweens too much,

Unless my hand and strength could equal them.

Then, since this earth affords no joy to me,

But to command, to cheque, to o'erbear such

As are of better person than myself,

I'll make my heaven to dream upon the crown.

William Shakespeare

George was given to "bouts of melancholy" when he drank and did morphine or opium. In those days you could buy morphine over the counter along with your monthly supply of Electric Bitters or Dr. Thatcher's Liver & Blood Syrup. He had recently told the proprietor of the Grand Avenue Hotel not to trouble with his body if he were found dead some day, but to toss it out the back door.

Early one morning George bought enough arsenic to kill a troublesome dog several times over. Everyone in the neighborhood, including the druggist's clerk, had heard the dog in question baying all night. George claimed he would ease everyone's sleep.

Back in his room, he swallowed the arsenic himself. A large dose of arsenic is a painful way to die. George's cries roused the house. His door was locked, but two men boosted a third over the transom into his room. The men found George convulsing on the bed. By the time a doctor arrived, George had lapsed into a coma. Soon he was dead.

His body was taken to W. B. Penniman's mortuary and furniture store. Two days later, Penniman's assistant was at work on the body when a couple named Harper came in. Before moving to Enid, the Harpers had lived in the nearby town of El Reno, where they had known George. Mrs. Harper said George had tried to kill himself with an overdose of morphine once before. Believing himself on his deathbed, he had told Mrs. Harper he was John Wilkes Booth, the man who killed Lincoln.

Soon others came forward with similar stories. A legend was born.

Published on September 27, 2011 09:11

September 26, 2011

Fellow Hunter Killed Grizzly Victim, Plus Another Bear Attack

Update on a previous story about hunters tangling with a grizzly in Montana. Earlier reports had said the wounded bear killed the man.

Hunter in Mont. grizzly attack shot by friend - TODAY News - TODAY.com:

"A hunter attacked by a wounded grizzly in a Montana forest was killed not by the bear, but by a gunshot fired by a companion trying to save him, authorities said Friday."

In another story, bow hunters startled a bear, which retaliated by breaking an arm. Authorities aren't sure yet which species the bear was.

Hunter in Mont. grizzly attack shot by friend - TODAY News - TODAY.com:

"A hunter attacked by a wounded grizzly in a Montana forest was killed not by the bear, but by a gunshot fired by a companion trying to save him, authorities said Friday."

In another story, bow hunters startled a bear, which retaliated by breaking an arm. Authorities aren't sure yet which species the bear was.

Published on September 26, 2011 22:28

American Crocodile

As promised--photos of the American crocodile, a specimen of which recently turned up in the unexpected locale of St. Petersburg, Florida. Photography by J.A. O'Ruiz Gutierrez.

Published on September 26, 2011 07:30

September 25, 2011

American Crocodile Turns Up in St. Petersburg

People find the most interesting things in their back yards:

Rare crocodile found by Florida woman - CSMonitor.com:

"Crocodiles — which number about 1,500 in the state — are typically found some 300 miles (500 kilometers) south in the warmer Florida Keys. But the shy and reclusive animals are so rare in places like St. Petersburg that a wildlife official didn't initially believe Shondra Farner when she called to report the crocodile."

I'll have more photos of American crocodiles tomorrow.

Published on September 25, 2011 09:00

September 24, 2011

Phases of the Moon Correlate with Lion Attacks

Interesting study on Tanzanian lion attacks.

The full moon indicates impending danger from lion attack, a University of Minnesota study shows : UMNews : University of Minnesota:

"A look at attack rates aligned with phases of the moon shows a clear pattern. The rate of human attacks during the first half of the lunar cycle (when there is lots of moonlight on most evenings) is one-third the rate during the second half (when there is little or no moonlight). Lions are hungriest just after the full moon because the abundance of light just before and during the full moon limits their ability to hunt successfully."

Photo by J.A. O'Ruiz Gutierrez

Published on September 24, 2011 09:56

September 23, 2011

Northern Red-Bellied Snake

Published on September 23, 2011 10:22

September 22, 2011

New Testimony in Fatal Killer Whale Attack

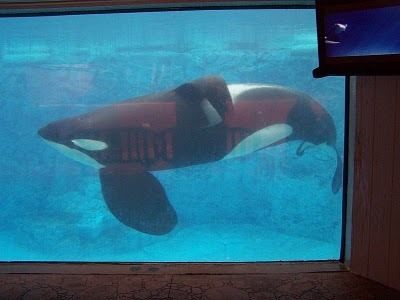

Tilikum, the Orca that has killed 3 people (Credit: Sawblade5/Creative Commons)

Tilikum, the Orca that has killed 3 people (Credit: Sawblade5/Creative Commons)OSHA disputes SeaWorld's findings about Orca attack on trainer - BostonHerald.com:

""From my angle, I saw her left arm go underwater as the whale started descending," Herrera said.

SeaWorld officials have said repeatedly since Brancheau's death that Tilikum grabbed her after her long ponytail drifted into his open mouth, which suggests the whale was reacting to a novel stimulus when he suddenly submerged with her. But some SeaWorld opponents have accused the marine-park operator of fabricating the theory to make Tilikum's actions that day appear more benign."

Published on September 22, 2011 09:00