Gordon Grice's Blog, page 77

October 20, 2011

Man Beats Woman with Frozen Armadillo

This news item provides a nice coda to our investigation of armadillos:

Man Allegedly Beat Woman with Frozen Armadillo:

"The altercation occurred when the suspect was selling the carcass to the victim, who planned to eat the animal.

The pair apparently began arguing over the price of the item when the man twice threw the armadillo at the woman."

Man Allegedly Beat Woman with Frozen Armadillo:

"The altercation occurred when the suspect was selling the carcass to the victim, who planned to eat the animal.

The pair apparently began arguing over the price of the item when the man twice threw the armadillo at the woman."

Published on October 20, 2011 10:00

October 19, 2011

Armadillos and Leprosy (Conclusion)

Dead ArmadillosNot that they meant it this way:

mostly mammal, mostly blind,

bellies up, stinking of leprosy.

The way Rasputin's mystical voice

led Annushka into his eyes

is how headlights lull armadillos.

They came to know the roar of full-lit ecstasy.

They fill our roadsides with their heaven.

--J. Rodney Karr*

*

Besides armadillos and mice,several other mammals had proved, or soon would prove, susceptible toinjections of M. leprae—rats, hedgehogs, ground squirrels. But scientists had always believed peoplewere the only natural host for the microbe. That's why they were shocked by a 1975 report of leprosy in wildarmadillos.

Several factors combined to make the situation seem like ahorror story. The wild leprous armadilloshad turned up in Louisiana, not too far from the site of experiments by Storrs,Kirchheimer, and others. The obviousinference was that experimental animals might have escaped, or at least thatthe carcasses of lab animals might have been cannibalized by wildarmadillos. If leprosy was new to thearmadillo population, there was no way to know how fast it might spread betweenarmadillos—or even into the human population.

At roughly the same time, the armadillo's conquest of theUnited States was fast becoming familiar to the average American. Newspapers reported the leprosy connection,creating the latest version of the deadly animal invasion story that seems tocrop up with a different cast of characters every few years (black widowspiders, killer bees, and fire ants have all figured in similarscare-stories). Finger-pointing among afew biologists didn't help matters.

Armadillos dig for insects and carrion compulsively, andthat trait had already given them a folkloric reputation as grave-robbers inparts of the south. The possibility ofarmadillos having contracted leprosy from human corpses was an alternative toblaming the scientists—though not an attractive one, since either scenario leftopen the possibility that people might be in for a wave of disease. Of course, scientists who worked with leprosyrealized that its threat was minor. Notonly does the disease progress slowly, but it is frequently re-introduced to theUnited States by human immigrants without spreading widely. These points were not always mentioned in thepress.

Other developments complicated the story. Chimpanzees came down with leprosy in 1977,as did sooty mangabey monkeys in 1981. In both cases, the primates were lab animals, but not the subjects ofleprosy experiments. These discoveries,which suggested that leprosy might occur naturally in any number of nonhumanspecies, lent credence to the idea that armadillos might have carried thedisease long before the species was used in leprosy research. Whether wild primates get the disease outsidelabs is still hotly debated; skeptics think humans infected a few chimps andmangabeys somewhere in the process of capture or lab work. To add another layerof mystery, no one has yet observed leprosy transmitted between armadillos incaptivity, but cage-mates of infected primates have come down with the disease.

In 1983, researchers reported leprosy in five people inTexas who had frequently handled armadillos. It was impossible to prove that armadillos were the source of the infection,since even now no one is certain of the disease's route of transmission, butthe implication couldn't be ignored. Since then, armadillos have been implicated in a number of other humancases. Why so many people would behandling armadillos puzzled me, since my only hands-on experience had been theridiculous armadillo race. Truman resolved my confusion: "People do eat quite alot of armadillo."

Truman and his colleagues finally put the question ofscientific culpability to rest in 1986. They tested blood samples which had been drawn from armadillos in theearly 1960s and kept frozen in a wildlife sera collection at Louisiana Stateever since. Truman's group found some ofthese samples contained definitive evidence of M. leprae. Since the samples predated the 1968 clinicalwork, Storrs and Kirchheimer and later leprosy researchers were off thehook. They couldn't have provided thefirst contact between M. leprae and wild armadillos.

But if scientists weren't to blame, who was? Leprosy is un-American; even today, NativeAmericans don't seem to get it. Trumanand company looked into the distribution of the disease in the U.S. In botharmadillos and people, the disease occurs most frequently in moist, low-lyingareas. So far, this generalization hasheld true for people on several continents. So perhaps M. leprae is hiding insome natural reservoir that occurs in such moist areas. It's already been established that themicrobe can survive for several weeks in soil, but no one knows whether ittypically does so.

Truman's survey could hypothetically have revealed anorigin point from which the disease was spreading. In fact, leprosy turned out not to followsuch a pattern. No point of originshowed up. The even distribution ledTruman's group to deduce that leprosy has been here a long time, in both humansand armadillos—maybe centuries. We'll probably never knw when M. leprae arrivedin America. Columbus's invasion marks the earliest possible date. And after thedisease arrived, it was only a matter of time until a cold and hungry mammal raidedthe wrong grave.

Hastily, all alone,

a glistening armadillo left the scene,

rose-flecked, head down, tail down.

--Elizabeth Bishop

A shorter version of this story originally appeared in Discover.

*J. Rodney Karr dedicates his poem to "all the little critters who have met their maker along America's highways and roads."

Published on October 19, 2011 09:00

October 18, 2011

Armadillos and Leprosy (Part 2 of 3)

My personal acquaintance with armadillos began at a freak show in the Oklahoma Panhandle in the early 1970s. The show's exhibits included a five-legged sheep, a three-legged chicken, a hairless Mexican "Elephant-dog," and, at the curtained end of the tent, to be seen only after payment of an extra dollar, a pickled, two-headed human baby ("Born to live," a taped voice kept saying, and when I asked my mother what that meant, she said we'd talk about it later, but we never have). And a Living Dinosaur.

Contrary to its billing, the Living Dinosaur was not actually alive. Its desiccated carcass was glued to a felt-covered board. A placard explained that this creature had existed "when dinosaurs ruled the earth" and had survived to the present day. The placard didn't make clear that the thing itself was not a dinosaur, despite its resemblance to a miniature triceratops. It was, in fact, an armadillo. A huge taxonomic blunder had been compounded with the slip of an era.

Nowadays, when armadillo knick-knacks litter eBay and caricatures of the animal have promoted everything from Lone Star beer to the professional baseball team of Amarillo, Texas, the "Living Dinosaur" fraud would fool nobody. But in the early 1970s, armadillos were unknown in the Oklahoma Panhandle and most of the rest of the country, though they had long been familiar to people in south Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. Since crossing the Rio Grande into the United States in the 1870s, armadillos have colonized most of the Southeast, their progress having only recently come to an apparent halt at the Rockies in the West and around the southern tip of Indiana in the north, where cold has barred them from further progress.

During the 1970s armadillos also colonized the consciousness of the American public, so that soon everybody seemed to know what one looked like. In the early 1980s I ventured downstate to attend college at Stillwater, Oklahoma. On my first trip there, though I no longer found armadillos exotic, I nonetheless found myself startled at the sight of several hundred dead ones. They littered the road and the right of way. The day was hot, and many of the carcasses had bloated, their legs jutting at forty-five degree angles. One in particular caught my eye: a car tire had halved it as neatly as a ripe watermelon.

This mini-apocalypse points to two interesting armadillo behaviors. One is a defensive tactic: when threatened, an armadillo springs straight up. This move is effective against most predators, but suicidal against cars. The other behavior is dietary: armadillos eat carrion, including dead armadillos, and the grubs and maggots they find therein. So a highway strewn with kindred carcasses apparently strikes an armadillo as an irresistible feast.

The armadillo family tree includes a number of interesting branches, including about twenty extant species in South America. Some of them look like opossums that have tumbled through a dryer's fluff cycle.

[image error]

Among their ancestors are an extinct North American species that weighed five or six hundred pounds. Their nearest relatives are the anteaters and sloths, with which they share some extra flexibility in the spine and a lack of well-developed, specialized teeth. The only armadillo found in the United States in modern times is the nine-banded species, so called because accordion folds in the middle of its back join the shell-like sections fore and aft. The armor is made of ossified skin. It's not hard like a tortoise's shell; it's more like stiff leather. The head and limbs sport plates of this armor as well.

Its unusual architecture causes the armadillo to copulate in the missionary position. Its young are normally identical quadruplets all wrapped in the same placenta, though occasionally it produces eight or twelve identical young. The fertilized armadillo egg can lie in its mother's reproductive tract for up to three years, bathed in nourishing fluids, before implanting. Some female armadillos, having mated only once, give birth to separate litters in successive years.

The armadillo's oddities don't stop there. It can gulp air until its digestive tract balloons, making its heavy body light enough to swim. Alternatively, it can stay deflated and walk underwater, holding its breath for as long as six minutes. It doesn't roll into a ball when attacked, as some of its southern relatives do, but it can plug a burrow entrance with its armored back and thrust its claws into the dirt so that it's almost impossible to remove. One authority claims a person can induce an armadillo to relax its grip by inserting a finger into its rectum, but I have not personally verified this fact.

One fact I have verified is that armadillos don't do well in captivity. When I was in college my dorm competed in an armadillo race. It was, if memory serves, part of a festival involving a pie-in-the-face auction and other such revelry. My dorm-mates and I went into the country a week or so before the event to capture our entrant. We went at night and took flashlights. A few miles out of town, we could actually hear the animals crashing around in a wash where people had dumped their trash. When a flashlight beam caught one, it paused, then turned with surprising grace and fled. It ran faster than I had expected, its pill-bug body scooting along like a drop of water sliding down a window pane, but its erratic course allowed us to catch up. The guy who grabbed it uttered increasingly vile profanity as the armadillo bruised his gut with stiff kicks. A flashlight beam showed the claws drawing a flurry of down from the guy's vest.

Once we had the armadillo back to the dorm, it stayed in our rooms. Whoever had it would go sleepless, because the thing wandered around all night, knocking over furniture and smacking into walls. We fed it an assortment of leftovers smuggled from the cafeteria; it particularly liked cantaloupe. We won the race by default because no one else bothered to catch an armadillo. Afterwards, we let ours go. No one had intentionally mistreated it, but its tail had somehow become ringed with wicked black wounds.

Though we didn't mean to be, we were cruel to capture the armadillo. We didn't know that captive armadillos may sleep around the clock, like human victims of depression, or refuse food and water. The males may dehydrate themselves by zealously scent-marking their cages with urine. The captives may suffer from boils or constipation. If several are caged together, they lick each other's wounds, keeping them open and weeping. Sometimes the licking turns to cannibalism. And they seldom breed in captivity, so armadillo colonies like the one at LSU have to be replenished with frequent new captures. Truman regularly sends his graduate students into the woods near Baton Rouge for more armadillos.

Such were the problems Storrs and Kirchheimer had to overcome in 1968, when they attempted to inoculate armadillos with M. leprae. Not only did the armadillos get leprosy, they got it more thoroughly than any human being ever had. Organs that remain untouched in the worst human cases were loaded with bacilli in the armadillos. With their twelve-year life-spans—much longer than those of mice and rabbits—the armadillos lived long enough to develop full-blown cases. This complete susceptibility is the reason armadillos remain the animal of choice for leprosy research. It comes down to numbers: an armadillo yields one million times more of the M. leprae bacilli than a mouse footpad.

Published on October 18, 2011 09:00

October 17, 2011

Armadillos and Leprosy (Part 1 of 3)

The Book of Deadly Animals makes its debut in the United Kingdom November 3. To celebrate, I'm running here some expanded versions of tales I told in the book. If you read the magazine version of this story, you've only seen about half of it; I've revisited this one to add more information and more of my first-hand experience with the animals. This is the director's cut.

Dr. Richard Truman and I dressed in gowns, disposablebooties, masks, and rubber gloves. Thenwe opened a door and stepped into an odor Truman had warned me about. It was something like a diaper pail and quitea bit like sour milk. I was glad for themask.

The room was full of cement runs – walls about four feethigh, forming rectangular pens about six by three feet. The cement floors were littered withsawdust. The dishes for food and waterwere just like those one might provide for a dog or cat—in fact, the foodincluded cat chow—but the residents here were nine-banded armadillos. An ordinary plastic kitchen trash can lay ineach run to serve as a burrow.

Truman, a tall, soft-spoken man whose silver hair didn't matchhis youthful face, asked a lab assistant to roust one armadillo from itssawdust. The animal looked like aninverted bronze gravy boat with a head and tail. The assistant gripped it at the back of theneck and the back of the tail—pretty much the only option if you want to avoidan armadillo's impressive digging claws. Truman let me hold the thing. Excluding the tail, it was about the size of a football, but heavierthan your average cat. It wriggled andflexed, kicking with all four feet. Itspink belly was studded with protuberances from which tufts of hair sprouted. These structures, Truman said, have a sensoryfunction.

After that brief hands-on encounter, Truman asked theassistant to put the armadillo back. They're sensitive animals, poorly suited to captivity, and too muchhuman handling can prove fatal for them. I was, in fact, allowed to see only the healthy armadillos at LouisianaState University, home to the Laboratory Research Branch of the G. W. LongHansen's Disease Center, and those only with strict sanitary controls. The ones with leprosy were strictlyoff-limits—I was more dangerous to them as a source of secondary infectionsthan they were to me.

I was there to learn about two mysterious organisms, bothpoorly understood even after centuries of contact with people. One, of course, is the armadillo; the otheris Mycobacterium leprae, the microorganism responsible for leprosy. Truman and other researchers are using theformer to study the latter. What they'vediscovered so far is a lesson in the complexity of the natural world.

*

The symptoms of leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease,start in the nerves. Patches of skinlose feeling. For some people, that's asfar as it goes. For others, things getmuch worse. Grainy, ulcerating lesionsappear on the hands, feet, and back, and, in men, the testicles. Nerves degenerate, causing the glands thatoil the skin to stop working. The skincracks, leaving the extremities vulnerable to secondary infections. People lose fingers and toes—not because ofthe disease itself, but because they don't notice that they're too close to afire or that rats are nibbling at them. The dead nerves create an array of odd postures—the claw-hand, thestaring eye that cannot be closed. Therespiratory system is invaded; a slimy discharge issues from the nose. The eyes succumb to infection and eventuallyto blindness. The disease progressesslowly, the first lesion following the actual infection by three years or more,the worst manifestations developing years after that. But these horrific symptoms occur in only atiny minority of those infected, and most people are not susceptible to infectionat all. "M. leprae is almost the perfectparasite," Truman said, because it so rarely destroys its host, and then onlyvery slowly.

The skulls of four Egyptians from the second century BCEhave curious deformities. Certain partsof the face seem to have eroded before death. These skulls are the oldest hard evidence of leprosy, one of the oldesthuman diseases. Detailed descriptions ofsymptoms in various documents push our known contacts with leprosy back evenfurther, to about 600 BCE. Beyond that,the vagueness of historical descriptions becomes a problem. There are accounts of a leprosy-like diseaseinvading Egypt from the Sudan during the reign of Ramses II. The disease mentioned with such horror in theBible may not be the same thing as modern leprosy—its symptoms are only vaguelyalluded to, and sometimes it seems not even to be a disease as we understandthe idea, but sin figuratively described. If the biblical references are to a literal skin-mottling disease, somecommentators find smallpox a more likely candidate.

But it's certain that genuine leprosy has peeked intohuman history at odd junctures, as when the soldiers of Alexander the Greatconquered the East and brought back silks, spices, and the disease. Europeans came back from the crusadesinfected—a public relations problem for the Church, since the crusades weresupposed to be a holy war, and leprosy appeared to place God on the otherside. For a few centuries, lepers' homesexisted throughout Europe. Leprosy'sdecline as a major health problem on that continent coincided with the BlackDeath, which tended to kill the inmates of lepers' homes and thus break themysterious chain of transmission for the older disease. But elsewhere in the world, leprosy has neverlost its hold. Half a million new casesappear annually, and the total number of people afflicted is at least tenmillion. India and Brazil currently have especially severe leprosy problems,but the disease occurs virtually everywhere in the world, including about 6000cases currently in the United States.

The notion that leprosy is contagious has been around forat least 2500 years, but a competing hypothesis blamed heredity. It made some sense: relatives of lepers provedmore likely than others to become lepers themselves. Western science dropped thehereditary theory in the 1880s, when a missionary named Father Damien, who hada well-documented and leprosy-free family background, was revealed to havecaught the disease while working with lepers on Molokai. By that time, aNorwegian doctor named Armauer Hansen had discovered Mycobacterium leprae, theorganism that causes the disease. The nasal secretions of people with severecases carry enormous quantities of M. leprae, and many physicians andresearchers assume that the microbe infects new victims through the respiratorysystem or through open wounds. Hansen immediately recognized the importance ofcultivating M. leprae for study, but he found he couldn't keep the bacteriumalive in a dish. Even now, no one hassucceeded in cultivating it outside a warm body. "It starts to die as soon as it's out of thetissue," said James Krahenbuhl, Truman's colleague at the G. W. Long Hansen'sDisease Center. Hansen tried to infectrabbits with M. leprae, but it didn't take.

In 1956, Chapman H. Binford, having noted that leprosyattacks the coolest areas of the human body, suggested that lab animals mightbe susceptible to infection in their cooler regions. By 1960, C. C. Sheppard had successfullyinoculated the footpads of mice. Soonmouse footpads and hamster ears were yielding fresh supplies of M. leprae,though never in the quantities needed for effective leprosy research. The fresh cadavers of infected humansremained the best source for the microbes.

Then the team of Wally Kirchheimer and Eleanor Storrsnoticed that armadillos are cool all over. At 30-35 degrees Celsius, armadillos run several degrees cooler thantypical mammals. The animal's armorprobably has something to do with its low temperature; it certainly makes thearmadillo a poor regulator of body temperature, as mammals go.

to be continued tomorrow

THE BOOK OF DEADLY ANIMALS

A different version of this story originally appeared in Discover.

Published on October 17, 2011 09:00

October 16, 2011

Crazy Ants Invade US

Interesting item: Crazy ants have moved north to colonize parts of the US. They've wiped out the imported fire ants in some regions. Animal invasions are nothing new, but we may see more of them as the globe warms and more northerly regions take on tropical or semi-tropical temperatures.

Hairy, crazy ants invade from Texas to Miss. - Yahoo! News:

"A camper's metal walls bulge from the pressure of ants nesting behind them. A circle of poison stops them for only a day, and then a fresh horde shows up, bringing babies. Stand in the yard, and in seconds ants cover your shoes.

It's an extreme example of what can happen when the ants — which also can disable huge industrial plants — go unchecked. "

Published on October 16, 2011 09:35

October 15, 2011

Walrus Invasion

[image error]

The US Geological Survey has recorded some 20 thousand walruses ashore on the coast of Alaska. Most of them should be on ice floes drifting over the continental shelf, where they can dive for clams and sea worms. The trouble is, global warming has melted a lot of the ice. This is not a good sign for the walruses or the rest of us.

Published on October 15, 2011 09:21

October 14, 2011

Piranhas Bite More Than 100 People in One Weekend

Alexdi/Creative Commons

Alexdi/Creative CommonsThe article below points out the interesting relationship between piranhas and certain other fish--each serving as both predator and prey for the other. Human fingers and toes get involved as well.

Piranhas attack beach in Brazil: 100 swimmers bitten in 1 weekend | Mail Online:

"A lake used by swimmers in Brazil has been attacked by piranhas that have injured more than 100 people.

Visitors to the inland Barragem do Bezerro dam, close to the town of Jose de Freitas in the Piaui province, were left with bitten heels and toes "

Published on October 14, 2011 09:21

October 13, 2011

Same Grizzly Linked to Two Yellowstone Fatalities

The bear that killed Brian Matayoshi in July is now known to have visited the site where another park visitor died and was eaten by bears in August. Because many bears scavenged the body in the August incident, there's no way to know if this particular bear killed the man.

Yellowstone Bear Euthanized After DNA Evidence Links Two Fatal Attacks - NYTimes.com:

"Brian Matayoshi, 58, of Torrance, Calif., was confirmed killed by the female bear near the Wapiti Lake Trailhead on July 6 (Land Letter, Sept. 22). Less than two months later, on Aug. 26, hikers found the mauled body of John Wallace, 59, of Chassell, Mich., on the Mary Mountain trail roughly eight miles away from the first attack.

DNA evidence obtained from hair and scat samples taken at the scene of the August attack showed the bear was at the site of the second attack and may have scavenged Wallace's remains."

Yellowstone Bear Euthanized After DNA Evidence Links Two Fatal Attacks - NYTimes.com:

"Brian Matayoshi, 58, of Torrance, Calif., was confirmed killed by the female bear near the Wapiti Lake Trailhead on July 6 (Land Letter, Sept. 22). Less than two months later, on Aug. 26, hikers found the mauled body of John Wallace, 59, of Chassell, Mich., on the Mary Mountain trail roughly eight miles away from the first attack.

DNA evidence obtained from hair and scat samples taken at the scene of the August attack showed the bear was at the site of the second attack and may have scavenged Wallace's remains."

Published on October 13, 2011 08:42

October 12, 2011

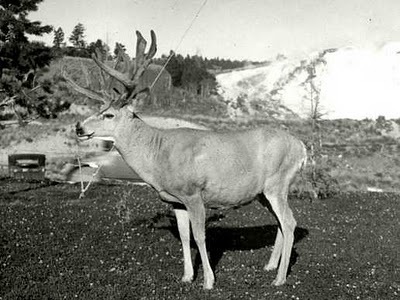

Mule Deer and Red Hartebeest Maulings

A mule deer launched an unprovoked attack on a woman taking a walk in rural Idaho. The article linked below emphasizes the possibility that the deer may have been domesticated, though there seems to be no evidence of that beyond its aggressive behavior. It's more likely the deer was in an aggressive mood because it's time for bucks to duel for mates. (The article mentions two other deer nearby; probably these two were involved in its excitement.) You and I know a human isn't interested in this buck's love life, but deer aren't as sharp as we are. Bending over to pick up a weapon was the last straw: to a deer, that looks like lowering the head for a charge.

Mule deer attacks woman near Preston - Mule deer attacks woman near Preston: Local:

"The deer knocked her to the ground. At that point, the buck began raking her body with his antlers, scratching and digging at her legs and back. Panter played dead, hoping that her lack of response would discourage the deer. But as the deer gored her in the legs three times and pummeled her upper body, Panter knew she had to fight back. She grabbed the deer's antlers and fought to keep the animal's head away from her face and neck.

"Scott Panter, Sue's spouse, said that his wife was trying to keep herself in plain sight on the roadway during the struggle. "She felt that if she got pushed off the road and into the cornfield, no one would see her struggling or even know she was there," "

Related Post: White-tailed Deer Attacks

Meanwhile, in South Africa, a competitive bicyclist ran afoul of a red hartebeest. Here's the video:

Published on October 12, 2011 09:20

October 11, 2011

Kangaroo Attacks 80-Year-Old Man

Attacks like the one described below occasionally happen with wild kangaroos in Australia. This one involved a captive and his keeper.

Kangaroo attacks 80-year-old man - UPI.com: "An 80-year-old man suffered injuries in an attack by a kangaroo he was feeding at an exotic animal farm in Ohio, officials said.

John Kokas was kicked and knocked to the ground by the 3-year-old kangaroo"

Photography by Dee Puett

Published on October 11, 2011 09:25