Gordon Grice's Blog, page 73

November 30, 2011

"Python" swallows "Hippo"

I've been seeing this spectacular video around the web for a couple of years now, usually labeled as a python vomiting up a hippopotamus.

But, as a close look at the feet of the prey makes clear, that's no hippo. It appears that this is actually an anaconda vomiting a capybara. The capybara is an immense rodent, the largest kind in the world, but, at a top weight of around 140 pounds, it's smaller than all but the youngest infant hippos. Big constricting snakes typically regurgitate large meals when they are harrassed, since it's hard for them to flee when laden.

Here's a different video of an anaconda preying on a capybara:

But, as a close look at the feet of the prey makes clear, that's no hippo. It appears that this is actually an anaconda vomiting a capybara. The capybara is an immense rodent, the largest kind in the world, but, at a top weight of around 140 pounds, it's smaller than all but the youngest infant hippos. Big constricting snakes typically regurgitate large meals when they are harrassed, since it's hard for them to flee when laden.

Here's a different video of an anaconda preying on a capybara:

Published on November 30, 2011 09:00

November 29, 2011

Blister Beetle

Nik Nimbus sends this video from a graveyard in England. The blister beetle is so named because it exudes an unpleasant chemical to ward off predators--though Nik says that, to his human nose, it actually smells like an agreeable incense. This particular kind of blister beetle lives by a sort of con game. Its larvae attract a male digger bee with pheromones. They board the lascivious male and use him as transport until he finds a female bee. She's the next leg of the trip. In her burrow, the beetle larvae feast on the pollen she's stored--and then on her young.

Published on November 29, 2011 09:00

November 28, 2011

Grice at OSU

I'll be speaking at Oklahoma State University tonight at 7PM in the Browsing Room of the library. Hope to see some of you there!

Published on November 28, 2011 05:00

November 27, 2011

A Closer Look at That Turkey

Published on November 27, 2011 09:00

November 26, 2011

A Keeper's Tale, Conclusion: Hope

Green Anaconda (Steven G. Johnson/Creative Commons)

Green Anaconda (Steven G. Johnson/Creative Commons)by guest writer Hodari Nundu

Because of that newly found respect for the life of insectsand rodents, I couldn´t help but feel uneasy while cleaning the rat cages.

It turned out that my friend who was scared of tarantulaswas also not particularly fond of rats. I couldn´t help but laugh at this, butI agreed to be the "rat handler" (the one who would take the rats out of thecages and into boxes during the cleaning) in exchange for him dealing with thepiles of rat excrement that were a lot less appealing to me.

We spent hours cleaning the rat cages and during all thattime, I couldn´t help but to notice that the rats would stand up on their hindlegs and look at me with great attention, following my every move. I wonderedwhat was going through their minds. Where they expecting to be fed? Or maybethey realized we were new? Whatever was in their minds, I couldn´t help but thinkthat they were rather cute. It was a shame that all of them would end up assnake food.

I wondered if the rats had any idea of what was going tohappen to them. And then I realized that I was talking to them. Whenever Imoved a female rat out of the cage, I would tell it that it was OK, that Iwouldn´t harm its pups, and that they would be reunited as soon as I cleanedthe cage. I would also announce that I had fresh, clean water for them. Andthen I would enjoy the sight of them happily drinking the clean water.

My friend, busy with the excrement and the huge garbage binin the other side of the room, wasn´t paying attention -- but I realized that Iwas being nice to the rats, and then it struck me that when the time came toget them out of the cages and break their necks. . . well, it would feel like treason. Maybe notfor the rats, because they were killed very quickly and painlessly (or at leastthat's what Salvador told us). But to me, it would be worse than beating themto death with the dustpan. I had cared for them and provided food and water forthem, and even comforted them when they were scared. After all of that, killingthem didn´t feel right at all. Yes, I knew and accepted the fact that in thisworld, some creatures have to eat others to survive. It is the way of nature. Butat least in the wild the rat had a chance to escape. Here, they had no way of avoidingtheir grisly fate.

There was no point in lying to myself. I was not meant forthis job.

Burmese Python (Hodari Nundu)

Burmese Python (Hodari Nundu)The moment came to tell Salvador the truth. I wasn´t willingto kill rats to feed the snakes. I knew that it had to be done- I just didn´twant to be the one to do it.

I must confess I felt kind of embarrassed. For anadventurous teenager like I was, it felt like being weak. I also expected himto be irritated; after all, if you go to a zoo asking to be a zookeeper, you'resupposed to be ready to kill a few feeder rats, right?

But he was actually quite nice about it. He told me that heunderstood, and he even allowed me to stay and become sort of a "presenter" forthe reptile house.

From that moment on, my job consisted basically in carryinga huge Burmese python over my shoulders and talking to visitors about snakes,their importance, and how they weren´t slimy monsters created by the Devil totorment human kind. I must say I really enjoyed this job. It made me feel likeI was actually doing something important.

Mexico is still the richest country in the world when itcomes to reptiles. However, at the same time, it is a very bad place to live ifyou are one. People kill harmless snakes and lizards out of fear and ignorance.Attacks on humans by crocodiles (even attacks caused by the humans themselves)are often followed by petitions to have the ancient reptiles culled. Manyreptiles are endangered, or have already gone extinct. Some people believe itis too late to save our wildlife. Cities are growing fast, jungles and forestsare being devastated; the future looks grim for many creatures.

Then again, some people are too quick to give up.

I always felt this way whenever I saw children looking atthe Burmese python in awe, touching its skin, wanting to learn everything therewas to know about it. There was a lot of interest- especially from the youngervisitors. Older people seemed less enthusiastic about changing their mindsabout the animals they had learned to fear and despise, but children wereeasily fascinated by the cold blooded creatures.

A ten year old boy surprised me one day with hisnear-encyclopedic knowledge on pythons. We spent over an hour talking about thebiggest Reticulated Pythons ever found, and about the snakes' amazing senses,hunting techniques and anatomical traits. I don´t think I ever had such a fluentconversation with an adult as I had that day with that kid. Nothing of what Itold him was new to him. Likewise, nothing of what he said was new to me, but Ithink he actually liked that. He probably had never spoken to another personwho enjoyed learning about snakes as much as he did.

Eventually, I had to take the python back to its enclosurewhen it became a little bit too interested in the boy's face. His grandfatherwas terrified, but the kid was exultant. When I asked the old man how did theboy know so much about snakes, he said "They're his passion. He is always reading about them".

Some time later, I was standing in front of the GreenAnaconda's enclosure. A little girl and her father were besides me. The girlread the information sign besides the snake's terrarium, and asked her father:

"What does endangered mean?"

"It means that there are very few of them left" said theman.

"Why?"

"Well, because people have hunted them too much".

The girl looked at her father, then at the thick, heavy,motionless green snake coiled in the corner of the terrarium. She looked at herfather again.

"That's terrible!" she said "We have to save them!"

I couldn´t help but to smile.

If little boys read tons about pythons, and little girls wantto save the anaconda from extinction, then there must be hope for the rest of thecreatures.

It is not too late at all.

Published on November 26, 2011 07:30

November 25, 2011

A Keeper's Tale, Part 4 of 5:: Hot Herps

Cantil--a hot herp. Photo by Hodari Nundu

Cantil--a hot herp. Photo by Hodari Nunduby guest writer Hodari Nundu

Salvador took us on a private "tour" of the reptile house,to show us how to feed and handle the different snake species he kept.

Most of them were harmless, but some were extremelydangerous. The most intimidating was without a doubt, the Green Rattlesnake,also known as the West Coast Rattlesnake. Found only in Western Mexico, it iseasily the largest rattlesnake in the country, sometimes rivaling even theEastern Diamondback in size. It is a particularly ill tempered snake, andbecause of its large size, the amount of venom it can inject into its victim isimpressive. Even though, being "hot herps," the rattlesnakes were off limitsfor beginners, Salvador allowed us to join him in the enclosure to show us howto feed them, as long as we stayed behind him.

The snakes weren´t happy to see us. There were several ofthem in the enclosure, and every single one of them adopted an attack postureand started rattling its tail. The sound was amazingly loud, and incrediblyintimidating.

A couple years later, I would read that the effect of arattlesnake's warning sound may be more powerful than we suspected. People whohad never heard it before, and even people who didn´t know what a rattlesnakewas, would become equally alarmed the moment they heard it.

But as intimidating as the rattlers were to my friend and me,they were not particularly scary to Salvador, who had worked with some of the deadliestspecies in the world.

He particularly remembered King Cobras. "They were veryscary" he said "even to an experienced snake handler. Some of them would risetheir heads vertically and look right at our eyes. And they can growl. Theygrowl like a turbine when they're mad".

He also had close calls with mambas and Gaboon vipers. Thezoo where he worked had both species together in the same enclosure. Thekeepers refered to that enclosure as "the terrarium of death."

But although a mamba once slithered up his back and into hisshoulder, forcing him to remain completely motionless for over half an hourbefore the snake decided to climb down, he was never bitten by any of thoseAfrican species.

When I asked him what was the snake he feared the most, hedidn´t hesitate.

"I have kept all kinds of snakes, and I can tell yousomething" he said "I would prefer to work with cobras or mambas anyday ratherthan with lanceheads".

*

The Spanish name for the lancehead snake is nauyaca real,which can be roughly translated as "royal pitviper". Its scientific name,infamous among herpetologists, is Bothrops asper.

It is the most dangerous snake in Latin America, and kills morepeople in Mexico than any other species. It has every trait that makes a snakedangerous: an aggressive, nervous temperament, a potent venom, the habit ofapproaching human settlements in search of rodents, and a proclivity to bitemany times in a single attack, thus injecting huge amounts of venom. In ruralareas where medical attention is difficult to get, most people bitten by thissnake die, and those who survive are left horribly scarred or lose entire limbsto the creature's highly necrotic venom.

There's a legend, often repeated among snake enthusiastsaround here, about a gigantic venomous snake (according to some versions, itwas eight meters long), that was kept in the Guadalajara zoo and managed toinjure or kill three keepers in a matter of seconds.

When my friend and I asked Salvador about this, he smiled.

"It was a lancehead, actually" he said "and it is true thatit bit three handlers within seconds. They were trying to force-feed it, butthey forgot that these snakes can bite even with their mouths closed. The fangsare very long and retractable, so they can stick them out of the mouth. That'swhat this lancehead did; it used one of its fangs to scratch the handler thatwas grabbing its neck. The man released it in alarm, and the snake immediatelyturned in the air at the man grabbing the middle section of its body and bithis hand. When he let go, the snake fell to the ground and bit the third manwho had been holding its tail. It was all over in seconds. All of the handlerslived, but one lost his hand. So in a way, the legend is true. The only partthat was added was the bit about the snake being gigantic".

After this conversation, Salvador showed us how to kill arat to feed it to a snake. Live rodents are rarely given to snakes in zoos;rodents are more than capable of biting snakes and causing them serious injury.This rarely happens in the wild, where the rodent has the much preferableoption of running away. In a small enclosure, however, rodents are no wimps.They will fight to the death to save themselves.

Before continuing I should probably mention that I don´tenjoy killing animals at all. I used to, though, when I was a kid. Me and mycat Pinky (in my defense, it was my sister who named him) would often team upto hunt insects in the house. I would swat the insects and Pinky would eat thecorpses. Whenever we encountered a dangerous specimen, like a scorpion(scorpions kill hundreds of people in Mexico every year), Pinky would replaceme as the main hunter and deal with the creature himself. Somehow, he alwaysmanaged to avoid being stung. Together, we were the perfect pest-managementteam during those rainy months when insects of all sorts wandered into thehouse.

I would also capture insects for a collection I had. I wouldtake the hapless insect and dip it into a jar with alcohol, alive. The insectwould struggle for a few moments before going still. Eventually, I had a smallmuseum of pickled cicadas, earwigs, scorpions and other arthropods, and wouldproudly show it to all my friends until my cat decided that it would be fun tosmash all the jars and spill the foul-smelling contents all over my bed.

This all changed when I was 13, and a mouse wandered intoour house. I immediately went after it, along with the cats. I don´t know how,but I got to the mouse before the cats did, and then, I used a dustpan to beatthe unfortunate rodent to death.

Once it was death, I just sat there, staring at themotionless body. Before that moment, all the lives I had taken had belonged toinsects. It is relatively easy to kill insects. They are small, they don´t havefacial expressions and they usually don´t make a sound when you squish them todeath. Yet the mouse, despite being small, was much more similar to a human. Itbled profusely, and it squeaked in fear and in pain when I struck it with thedustpan.

It made me feel terrible about myself. Had my cats caughtthe mouse, its fate wouldn´t have been much better; Pinky, in particular,enjoyed playing with live mice before eating them. But at least he was meant tokill mice. He was a cat after all. I had no need to kill the mouse. Not in sucha brutal manner, anyways.

That episode got me thinking about death a lot. Even insectcollecting seemed wrong now. Insects, I figured, had naturally short lifespans,and it didn´t seem right to make them even shorter just so I could show theirpickled corpses to people who really didn´t enjoy the sight anyways.

That was the end of my insect-collecting days. Nowadays,whenever I go hunting for bugs, it is with a camera. I must say, getting a goodpicture of a fantastic looking insect and then letting it fly away is much morerewarding than putting it into alcohol.

As for mice, whenever one gets into my house, well, that'swhat cats are for. I just hope they don´t start feeling remorse too oneday.

Next: Hope

Published on November 25, 2011 09:00

November 24, 2011

A Keeper's Tale, Part 3 of 5: Crocodiles and Caimans

by guest writer Hodari Nundu

I should probably say a few things about crocodiles in Mexico.We have four species of crocodilians. One of them is most familiar forAmericans-- the American alligator. Officially, gators have been extinct inMexico since the nineteenth century. However, a few of them are seen and evenphotographed every now and then in the country's northernmost rivers and lakes.

In the southern states of Oaxaca and Chiapas lives a morecommon, but still seldom encountered relative to the alligator. It is thespectacled caiman, which can grow up to three meters long and is notoriouslyable to change color- although its ability to do so is very limited compared tothat of say, a chameleon.

Caimans are usually considered to be harmless to peopleunder normal circumstances; they rarely grow large enough to devour an adulthuman. However, they have quick reflexes and their teeth are sharper than acrocodile's; they are, as all wild predators, better left alone.

In the southeastern states lives the Mexican crocodile, alsoknown as Morelet's crocodile. Once on the verge of extinction due to hunting,it is now a protected species, and its population is on the rise. Recently, aswimmer was attacked by one near a popular touristic destination. However, mostattacks by these crocs are territorial, or triggered by a female's maternal instinct.Indeed, Morelet's crocs are ferociously protective of their nests and young.

I learned this during a trip to a crocodile breeding centerin Colima. The area was natural American croc habitat; there was a lake whereyou could see the larger crocodiles -- the males -- patrolling for potentialintruders.

There were also Morelet's crocodiles, but since they weren´tnative to the area, they were kept in enclosures to keep them apart.

I noticed that one of the female Morelet's had a nest, and gotan idea for a little experiment. You see, one of my secret talents is mimickinganimal calls. I am particularly proud of my American alligator mating call --which I certainly do not intend to use in gator country. Although some peoplehave praised my mockingbird-like talents, truth is I appreciate critiques byanimals even more. I took it as a compliment when I managed to frighten thezoo's chital deer by mimicking their tiger alarm, or when I caused a maleleopard to go ballistic after mimicking the big cat's territorial call. Becausethe leopard had seemed ready to leap out of its enclosure that time, I hadpromised myself to stop mimicking animal calls in front of the real things.

But that day in the crocodile breeding center I simplycouldn´t resist. Seeing that the mother crocodile was basking besides its nest,I started imitating the chirping call of a baby crocodile.

The female's reaction was explosive. I don´t know what wentthrough her mind; maybe that her babies were about to be born, and that thehuman standing beside her enclosure had to be frightened away immediately. Ormaybe she assumed that I had abducted one of her babies, seeing as the soundcame from outside the enclosure. I also considered the possibility that shemight have recognized my call as a fake, and was angered at my vocalincompetence to the point of charging the fence, slamming her heavy armoredhead against it and letting out a veryloud warning hiss.

I didn´t bother her further after that. I was lucky therewas a fence between her jaws and me!

The fourth and largest crocodile species in Mexico is theAmerican crocodile. In Spanish, it is often called the "cocodrilo de río",meaning "river crocodile", whereas the Morelet's crocodile is called "cocodrilode pantano", "swamp crocodile". However, these names can lead to confusion asboth species can be found in either rivers or swamps. In fact, the Americancrocodile is not very picky about where it lives. It has been seen even in the sea,and recently a man was attacked by one while repairing his yatch in the Pacificcoast. This is why it is also known as the "American saltwater crocodile".

When Steve Irwin visited Mexico, he expressed his surpriseat the docility of American crocodiles. But although they may seem mellow whencompared to their infamous Australian relatives, American crocs are not to beunderestimated. In the US, where crocodiles are extremely rare, attacks onhumans were unknown until very recently. In Mexico, it is a very differentstory. American crocodiles are numerous and widespread -- protected by the law,they have recovered after decades of ruthless extermination. Attacks on humans,many of them fatal, have been recorded along both coasts of the country.Usually the victims are drunken men who ignore warning signs and go for a swimin crocodile-infested rivers. Sometimes, it is playing children who getsnatched. Livestock, including horses and cattle, are also taken.

American crocodiles are responsible for most predatoryattacks on humans in the country. Compared to them, American black bears,jaguars and cougars seem rather shy.

Although the eight-meter long individuals reported by afamous zoologist from Chiapas seem to be a thing of the past, large malesmeasuring over five meters are still found regularly. The same breeding centerwhere I provoked the female Morelet's used to be home to a six and a half-meterlong American crocodile, said by the gamekeepers to be possibly over a hundredyears old.

Unfortunately, this giant was murdered when it wandered awayfrom the lake and into the woods, where it was found by hunters.

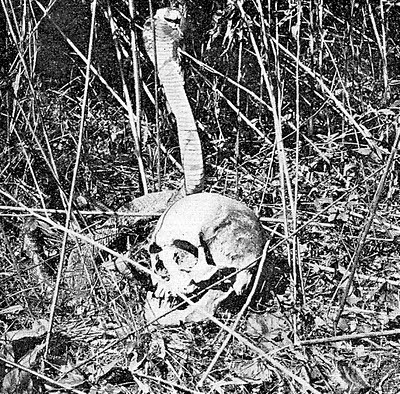

The breeding center kept the giant crocodile's skull as areminder of the huge size attained by these reptiles, provided they are giventhe opportunity to grow up in peace.

It was this largest, most aggressive species we'd be workingwith at the park. But before we were allowed into the croc enclosure, we had tostart with other, less dangerous reptiles.

Top photo: Morelet's Crocodile/Hodari NunduBottom photo: American Crocodile/Hodari Nundu

Next: Part 4: Hot Herps

Published on November 24, 2011 09:00

November 23, 2011

A Keeper's Tale, Part 2 of 5: Iguana-Infested Woods

Wayne T. Allison

Wayne T. Allisonby guest writer Hodari Nundu

Being rejected as a shark keeper meant that I had to findanother job. That's when I got the cartoonist job at the local newspaper. Iactually had applied to be an article writer, but the director told me thatthey didn´t need any at the moment-- they were instead looking for a politicalcartoonist.

Now, I hate politics. I don´t even believe in democracy.This doesn´t mean I don´t like theconcept- I just think true democracy can never be achieved. When I was inhighschool, I wrote an essay on that. I think it was called The Evolutionary Reasons for Democracy Beinga Utopia, or something like that. Myteachers hated it. They also hated me for a while.

But I really needed a job, and I could draw, so I thought,"what the heck? Let's give it a shot".

I took the job, and the cartoons, as ugly as they were,became an instant hit. Even the local politicians being spoofed asked me forthe originals to frame them on their office walls! My boss was so happy with mywork that he gave me a raise in my second week.

At about the same time, I was trying to figure out whatcareer to study. A friend of mine suggested that I studied the same as him;graphic design. After all, it would be easy for me, seeing as I could draw verywell already.

I wasn´t so sure about this, because I knew graphic designinvolved more technical drawing (which I always sucked at). However, I had noidea what other thing to study. Zoology and paleontology don´t exist as careersaround here. So I eventually agreed to travel to my friend's hometown andbecome his roommate.

His hometown was the city of Colima, near the coast of thePacific. Foreigners perhaps know about Colima because it's near Manzanillo, apopular tourist destination which claims to be "the sailfish capital of theworld" (although I'm told certain American cities make the same claim).

Anyways, I had always lived in relatively colder places, soliving in Colima was a complete change for me. The heat was almost unbearable;so much in fact that we barely went out of the house during daytime. The goodnews was that, being a tropical place, Colima was much richer when it came tocreepy crawlies of all kinds. My friend wasn´t very happy about it. One day, wefound a Mexican Red-Knee Tarantula near the garbage bins outside the house. Myfriend couldn´t believe it when I picked the hand-sized spider up and allowedit to crawl over my shoulders and neck. "It's really not that dangerous," Isaid. "Its venom is weak. The worst thing it could do would be to send its saetae into your eyes. That would be nasty but,it won´t do it unless it feels threatened".

Hodari Nundu

Hodari NunduThat wasn´t very comforting to him. He was relieved when Ireleased the tarantula in the iguana-infested woods near the house.

Seeing as my friend was scared of a relatively harmlesstarantula often kept as a pet by small children, it may seem ironic that he wasmadly in love with crocodiles. In fact, it was he who invited me to try my luckas a zookeeper once again, when he found out that a local park kept Americancrocodiles (the largest species in the country, reaching up to six meters long,sometimes more).

"We could both apply for a job there," he said. "It's notvery far away".

Of course, I loved the idea.

The park was not very large. In fact, there were very fewanimals in the zoo -- a couple male lions in a cage, a jaguarundi with abroken-tail, some spider monkeys, and tons of rabbits. As I would later findout, the rabbits weren´t really meant to be an exhibit. They were bred asreptile fodder.

My friend and I immediately went to the reptile house. Therewere two crocodiles in an enclosure, both were about three meters long. Smallfor an American crocodile, but big enough to overpower a man.

There were almost no visitors in the park, and it wasn´thard to find the chief zookeeper- who was also the chief vet and residentbiologist. He had worked once in the same zoo where I had tried to become ashark keeper, and after moving to Colima, he had founded his own reptile house.Reptiles, he told us, where his passion.

"So, are you guys studying Biology?" he asked.

"No," we said nervously. We immediately assumed he only tookBiology students as assistants.

However, he didn´t seem disappointed. "It's OK. My only assistantright now is actually a computer programmer," he said, referring to a guy wehad seen offering advice to a ball python owner whose pet wouldn´t touch itsfood.

Salvador (that was his name) told us that he couldn´t pay usa lot, but that he would be happy to accept us as assistant zookeepers.

"There's one thing, though," he warned. "Lions are offlimits for beginners. So are hot herps (very venomous snakes)."

"What about crocodiles?" I asked.

Surprisingly, he said crocodiles were fine, as long as hewas there to guide our every step. And that's how my brief career as anassistant zookeeper began.

Next: Crocodiles and Caimans

Published on November 23, 2011 09:00

November 22, 2011

A Keeper's Tale, Part 1 of 5: Sharks

by guest writer Hodari Nundu

I am kind of an artist. I've been drawing since I was threeyears old. That's also about the time I became obsessed with dinosaurs and allsorts of wildlife both living and extinct. Most of my drawings depicteddinosaurs, rattlesnakes with impossibly long rattles, and sharks, along withcomically square cars with oversized radio antennae. Today, I believe I ampretty good at drawing dinosaurs, rattlesnakes and sharks- my cars still lookthe same, though.

I have a job as a cartoonist in a newspaper and I draw a lotwhen I have free time. Also, I write- both fiction and non-fiction. In otherwords, I use my fingers quite a lot. This is the reason why, despite wishing tobecome a zookeeper since age 15, I always hesitated a bit.

Anyone who has read anything about wild animals in captivityknows that being a zookeeper is no joke. All young boys and girls who dream ofbeing zookeepers or animal trainers seem to operate under the impression thatthey will magically develop a close bond or relationship with their animalcharges, and that it will be awesome to have a ferocious tiger or gigantickiller whale following your commands and being as loving and obedient as apuppy as the crowd watches in awe.

But I always knew reality was nothing like that. I knew that zookeepers had adangerous job. They were often mauled, envenomated, trampled, even crippled orkilled. Although wild animals are indeed capable of bonding with their keepers,provided they are treated with respect and that their needs are fulfilled as muchas possible, that doesn´t mean they become puppies. A leopard cannot change itsspots. And leopards have been eating humans since prehistory. Even years oftraining can´t beat millions of years of predatory instincts.

What worried me the most, as a teenager trying to figure outwhat he wanted to do in the future, was not the (very real) danger of beingmauled to death by a zoo animal. I wasn´t very afraid of death at the time. Iwas more worried about my fingers. I had been told that one of the most commoninjuries zookeepers suffered was the amputation of fingers. Either directly,due to the bite of an animal (and a surprising number of finger-choppers werenot even predatory), or indirectly, as a desperate measure to save someone fromdying a painful death. A friend of my father's had worked at the local zoo. Hetoo was an artist- he painted the jungle-mimicking backgrounds to the snakeenclosures in the reptile house. He told us that an unfortunate snake-keeperhad been bitten in a hand by a Gaboon viper- one of the deadliest snakes in theworld, and the record-holder when it comes to the longest fangs of any snake.

Gaboon Viper (Ltshears/Creative Commons)

Gaboon Viper (Ltshears/Creative Commons)There was no antivenom available at the time, and so theyhad to chop the man's hand with an axe to prevent the venom from spreading to hisbody. He lived, but his story was scary enough for me to think twice about mywild dream. After all, as much as I loved animals, I loved drawing and writingjust as much, and I needed my hands and fingers intact to do that.

For a little while, I forgot about the zookeeping dream.Then, one day, the local zoo made anannouncement. The exhibit formerly known as the Nocturnarium was to be closedpermanently, and all the animals in it- which had been caught in a nearbynatural preserve- were to be released back into the wild, except,unfortunately, for the vampire bats, since the risk of having them infect thewild ones with a disease was too high (it had to do with the vampire habit ofregurgitating blood meals into the mouths of hungry mates).

The good news was, the Nocturnarium building would beadapted into an Aquarium. And there were going to be sharks.

Now, sharks are among my favorite animals. When I was a kid,a group of friends and I found a requiem shark's severed head in a beach. Somebelieved that the shark had been beheaded with a machete, perhaps by afisherman. However, it made little sense to me, as I figured a fisherman whotakes the time to hack a shark's head off would probably keep the head insteadof throwing it away. Besides, it didn´t look like it had been cut off with a machete.In fact, the head bore every sign of having been bitten off by another, biggershark. I asked a local diving guide if there were any large sharks around. Hesaid the biggest he had seen were about four meters long.

However, my favorite encounter with a shark, although notvery close, was when my family and I went on a brief tour in Puerto Vallarta onboard of a small yatch. The yatch was taking us to a small island nearby (which,as we eventually learned, was teeming with leeches). It was the journey to theisland that was interesting. I saw hundreds of bright blue Man'O'War andjellyfish, and a pod of bottlenose and spotted dolphins swam besides the yatchfor a while.

Also, we saw a shark. I couldn´t tell what species it was.All I know is that it was too busy feeding on a huge fish shoal to pay us anyattention. But even the brief glimpses of its dark, triangular dorsal fin wereenough to hypnotize me. I had seen a shark, alive, in its natural habitat. Myfascination with these animals was even greater since that day.

So of course, as soon as the sharks arrived to thenewly-inaugurated Aquarium, I went to visit. Once again, I was captivated bytheir beauty, their elegance, the way they glided through the watereffortlessly, almost as if they were ingravid creatures from another dimension.I spent over two hours standing in front of the tank, ignoring the noisychildren around me, and the desperate guard who kept telling people, to noavail, that it was forbidden to touch or hit the glass. After a while, Idecided that I wanted to be a shark keeper. I knew it was dangerous and Isuspected that no self-respecting zoo would allow an unexperienced boy to dealwith such umpredictable animals without previous training. But I still wantedto try my luck. I went looking for the Aquarium managers and asked them manyquestions about the sharks. I was told that all of the Aquarium's sandbarsharks were females (although I had already deduced this by looking at their pelvicfins), and that they all had names. The names were all rather comical- it is apart of Mexican culture to make a joke out of everything. Unfortunately, I haveforgotten the names. They also told me that the keepers only went into the tankwhen it was absolutely necessary.

When I asked them if I could apply to be a shark keeper,they told me just what I expected. I needed previous experience working withanimals. The zoo was very strict about who got to work with the creatures. Onlyvets and veteran biologists had that privilege. Of course, they said, I couldalways apply for a more normal job at the zoo- a cleaner, for example.

Needless to say, I didn´t even consider it. Not because Ithink being a cleaner is demeaning-- but because what I wanted was to be in thewater with the sharks, to look at their eyes and touch them and feed them,hopefully with some other creature's flesh instead of mine.

I was a little bit disappointed but at the same time, I wasrelieved. My hands weren´t in danger of being bitten off for the time being.

I still dream of swimming with wild sharks, or going on oneof those cage-diving trips to Isla Guadalupe, an island in the Gulf ofCalifornia which is known as one of the best spots to see great white sharks upclose. To date, none of my friends or relatives understand why I would want togo into the water with a two-ton predator known to bite human limbs off as ifthey were made of butter.

I really don´t know the answer, to be honest. Maybe I'm justan adrenaline junkie. Maybe I'm just madly in love. I am terrified of death,but there is one thing that terrifies me even more; the idea that the greatwhite shark may go extinct before I get to look directly into its dark blueeyes. Somehow, I feel I will not becomplete until I do.

Next: Part 2: Iguana-Infested Woods

Published on November 22, 2011 09:00

November 21, 2011

Grice Comes Home to OSU

I'll be returning to my alma mater, Oklahoma State University, next week! Monday night (7PM in the library's Browsing Room), I'll read something thrilling from my books. It's free and open to the general public. Tuesday morning, I'll join OSU's own distinguished nonfiction writers for a panel discussion. (I imagine that one's just for OSU students and faculty, but I won't tell anyone if you sneak in.)

Published on November 21, 2011 09:00