Gordon Grice's Blog, page 78

October 10, 2011

Hendra Virus Outbreak in Australia

Hendra Outbreak Attacks Queensland and NSW | News Tonight Africa

In Australia, an outbreak of Hendra virus has put horses and humans in danger, as detailed in the link above. Hendra is a Paramyxovirus found in bats.

Paramyxoviruses cause such human diseases as mumps and measles and such animal ailments as distemper, Rinderpest, and Newcastle disease. In recent years three more paramyxoviruses have emerged as threats to human health:

Hendra virus was formerly known as Equine morbillivirus. The natural reservoir for this virus appears to be fruit bats of the genus Pteropus. Through some route not yet identified, it occasionally passes to horses, causing a small outbreak of pneumonia. Human handlers have caught the disease from horses in a handful of cases. A few have died. People do not seem to get the disease directly from the bats, even when handling them. Scientists have recently diagnosed a case in a dog that lived on the same property as some infected horses.

Nipah virus also occurs in Pteropus bats. It has emerged as yet another consequence of human hunger. As farms expand into previously unsettled areas of Malaysia, India, and Bangladesh, domestic pigs come into contact with the feces of fruit bats and with fallen fruit from which the bats have eaten. The pigs contract the virus, which causes them to get sick with respiratory symptoms. Humans who contact the pigs have come down with similar symptoms in some outbreaks; in others, encephalitis has been the main manifestation of the disease. A 1999 outbreak in Malaysia killed 105 people. Half a dozen other outbreaks are on record, some of them killing 75 percent of known victims. A few single cases have also been documented. Once the virus crosses into human populations, it can spread directly between people. There's good evidence that some people have caught the disease from fruit contaminated by the bats themselves. Other bats besides the Pteropids carry the virus, but so far no evidence has linked them to human cases of the disease.

Menangle virus also has a reservoir in bats and has proved capable of infecting pigs. In 1977 it made two Australian farm workers seriously sick with respiratory symptoms.

Photo: Paul Asman/Jill Lenoble: Creative Commons

Published on October 10, 2011 09:31

October 9, 2011

Elk

Published on October 09, 2011 09:09

October 8, 2011

Diana Nyad vs. The Cnidarians

By now I'm sure everyone who's interested has heard about Diana Nyad's failed attempt at swimming from Cuba to Florida. The animals that stopped her with their paralyzing stings have been variously identified as Portuguese men-of-war (by Nyad herself in the video above) and box jellyfish. The man-of-war isn't technically a jellyfish, but a colony of hydroids. In The Book of Deadly Animals, I reported that at least three people have died from their stings. That's a tiny percentage, but pretty much everyone agrees the stings are painful. As for box jellyfish: many different species exist, some of them among the most toxic animals in the world, others not so dangerous to people.

All of these creatures--Portuguese men-of-war and other hydroids, and box jellyfish, plus the not-suspected-in-this-case true jellyfish and sea anemones--are members of a group called cnidarians. They all have stinging cells they use for self-defense and to help them kill prey. Nyad and her fellow humans are too large to serve as their prey, but these guys literally have no brain and aren't aware of their limitations. On the other hand, Nyad herself speaks of dreaming beyond one's expectations. It sounds inspiring when she says it, not so much when the cnidarians do it.

Related Post: Giant Jellyfish Attacks New Hampshire

Published on October 08, 2011 09:41

October 7, 2011

Great White Shark Attacks Man, Bites Off His Legs

The video shows the shark that attacked a British tourist in South Africa.

Shark attack: Brit loses both legs after savage attack in South Africa - video - mirror.co.uk:

""On arrival, a 42-year-old man was found on the shore suffering complete amputation of his right leg, above the knee, and partial amputation of his left leg, below the knee.

"The man was conscious when paramedics attended to him on the beach"

Published on October 07, 2011 09:51

October 6, 2011

Dog Bites Off Woman's Face; Leeches Help Reattach It It

Medicinal Leech (Credit: H. Krisp/Creative Commons)

Medicinal Leech (Credit: H. Krisp/Creative Commons)Leeches are frequently used in reattachment operations. Their saliva helps fight clots and infections, as well as restore circulation.

Swedish surgeons reattach woman's face using 358 leeches after horrific dog attack | Mail Online:

"Swedish surgeons have used hundreds of leeches to help reconstruct a woman's face that was bitten off during a horrific dog attack.

The woman, from the south of the country, had a huge proportion of her face bitten off in the mauling by her own dog, spanning from her upper lip all the way to her eye."

Published on October 06, 2011 09:30

October 5, 2011

Cicada Country

A cicada emerges from pupation. Photography by D'Arcy Allison-Teasley. Music by Incorporal Air.

Cicada Country(a memory of my hometown)

Summer mornings I often found gargoyles newly risen from subterranean sleep. They would climb the fence before the heat rose and then, their pupal shells splitting down the back, emerge from themselves in a final molt.

They sunned their crimped, wet wings, their greens drying and browning to match the short grass. Then they'd leave their shells on the weathered wood and take flight. I wouldn't often see them after that, but some days when I woke they'd been screaming so long it sounded like silence.

That arid country had, thanks to humans and their imported trees, become the cicadas'. They marked the territory with their bullet-hole burrows, their discarded shells. One morning I found a wing on my porch making a filigreed gesture of light with its veins. I held it to my eye like a monocle to see it slice the world into raindrops.

Published on October 05, 2011 09:00

October 4, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 7

Go to the beginning of this story

When the mummy's drawing power began to dwindle, Penniman finally handed it over to Bates, who had been claiming it since the beginning. Bates planned to make the mummy a sideshow, but couldn't raise the cash. So he rented it out to other exhibitors, and John Wilkes Booth, or at least his facsimile, was back in show business. The corpse traveled as part of a show featuring lavish live marriages and freak animals. It emerged unscathed from a train wreck that killed eight people, which may have been when it picked up the legend of a Tut-style curse. Tutankhamen had only recently been dug up, and such stories were in vogue. It got kidnapped and ransomed. It was offered to Henry Ford for his museum in Dearborn, Michigan; Ford had the mummy investigated and found its credentials dubious.

By 1931, the mummy had somehow fallen into the possession of a Chicago woman named Agnes Black, who purportedly bought it for $8000. Black, and the Chicago Press Club, arranged for a group of Chicago doctors to perform an autopsy to establish the mummy's authenticity. The doctors, led by Orlando Scott, used Finis Bates's book as a starting point. Bates listed Booth's physical imperfections -- a scar over his right eyebrow, the result of an accident during a stage duel; the left ankle broken in his leap to the stage at Ford's theater; and a deformed right thumb crushed by a piece of stage gear. The thumb injury seems to have been unknown in Booth's life before 1865. Bates apparently found out about it from a woman who claimed to have married yet another post-war Tennessee Booth.

Using gross examination and x-rays, the doctors supposedly found evidence of all three anomalies. An autopsy report signed by half a dozen physicians was issued to the press. The surgical scar on Booth's neck is not mentioned in the report. But it is mentioned in an affidavit signed by two doctors who refused to sign the report. One of these renegade physicians attested that he had used a fluoroscope to look for scar tissue on the mummy's neck--and found none. He said Orlando Scott had asked him to lie about this finding and go along with the "publicity stunt." Dr. Scott told newspapers the x-rays had revealed a metal fragment in the mummy's stomach, which the doctors retrieved by cutting through the mummy's back. The fragment proved to be part of a signet ring bearing the letter B. The autopsy report does not mention the ring.

Booth scholar Blaine Houmes, who is also a physician and a deputy medical examiner, has seen the x-rays. He says they show no sign of a broken leg.

In 1932 a retired carnival performer named Barney Harkin owned the mummy. Harkin had worked as a tattooed man before settling down as a landlord in Chicago. The mummy lured him back. The eccentric Harkin believed Napoleon had escaped after Waterloo and a dummy had been sent to St. Helena in his place. That John Wilkes Booth was for sale in Chicago did not strike him as utterly improbable.

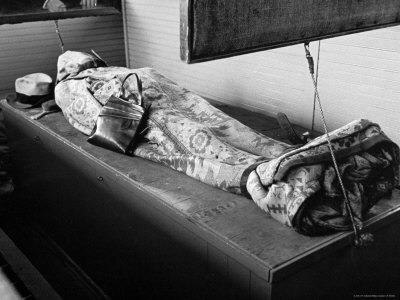

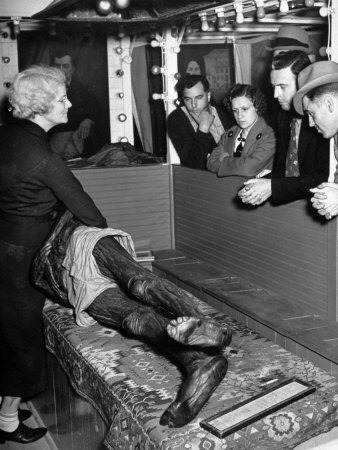

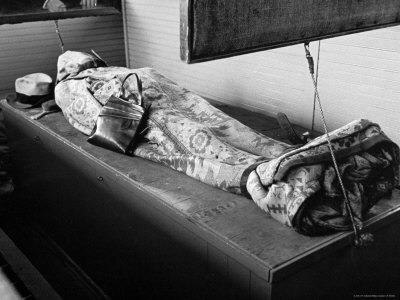

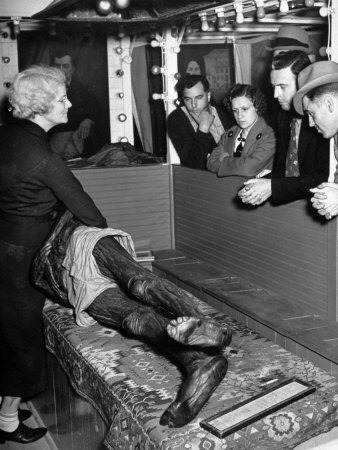

Harkin and his wife Agnes ran their show from a truck in which they slept at night, the mummy bunking between them for safety. Barney handled the gate; Agnes lectured the crowd, showing the Chicago x-rays and turning the mummy to show its shortened left leg. Hecklers sometimes claimed the figure was wax; she silenced them by rolling the mummy on its side and opening a flap in its back that had been cut at the autopsy. The mummy wore nothing but khaki shorts, and between shows Agnes Harkin lacquered its skin with Vaseline and combed its hair, which had gone white since the day David E. George expired with an atrocious dye job decades earlier.

Barney Harkin toured with the mummy into the 1950s. He died a destitute widower in Philadelphia. His landlady seized the mummy in lieu of his unpaid rent. The building where she stored it was demolished, and the mummy's trail since then has been difficult to follow. Scattered reports had sideshows exhibiting the as Booth mummy as recently as the mid-70s, alongside a pickled set of Siamese twins and the car in which Jayne Mansfield was decapitated. All sources seem to agree it's now in the hands of "a private collector," but this person declines to speak with the press.

Ken Hawkes, an autopsy assistant from Memphis, spent a decade searching for the mummy. If he ever finds it, he'd be happy to buy it. But he'd settle for a few clippings and scrapings for testing and maybe a full-body x-ray. That sort of evidence might settle the debate for good. He estimates he has checked out 2,000 leads. He once came across a collector who owned the mummified leg of a victim in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, and other collectors who had complete mummies of 1920s gangsters. One lead pointed to Seattle, where Ye Olde Curiosity Shop exhibits a mummy named Sylvester. Sylvester had indeed worked under the name John Wilkes Booth at one point in his own sideshow career, but old photos of the mummified David E. George make it clear that Sylvester was only a knock-off. Sylvester's true identity has never been established.

Hawkes located several mummies kept in homes. Some of these are relatives of the people they now reside with. According to Hawkes, the publicity surrounding David E. George in the early 1900s created a fad for mummifying relatives with a combination of arsenic and formaldehyde.

Blaine Houmes says the x-ray pictures from 1931 are studded with granules of a heavy metal -- doubtless arsenic. If the mummy still exists, the concentration of arsenic in its tissues makes it a health hazard. The elusive "private collector" may be breathing in death every day, dying of slow poison even as he hoards his immortal emblem.

Four months after my first expedition to Enid, I make another. The town has been invaded by a heat wave and a steer convention. The sign on a bank says 103 and the marquees on the hotels say WELCOME INTERNATIONAL BRANGUS ASSOCIATION. Brangus are a breed of cattle compounded of Brahman and Angus. I go to see the Brangus at the fairgrounds and, though no events are going on at this particular time, I see people in Wranglers and oversized belt buckles grooming their velvety black castratoes. They've been brushed to an exquisite lacquer, like contestants in a beauty pageant. When a steer looks at me it's like gazing back into two cups of black coffee.

I visit the cemetary where lies the body of Dolly Douthitt, the colorful murderer the man at the museum told me about. The trees all around have a curiously ordered appearance, even for a cemetary. After a while I realize why. All of them, pines as well as elms, have been pruned up to about ten feet, so that the whole expanse of the cemetary is visible under a green canopy. Through that canopy I can see hawks wheeling in the clear sky. The tune of the Oklahoma state song, from the Broadway musical, suddenly crawls through my mind: "Sit alone and talk, and watch a hawk makin' lazy circles in the sky. We know we belong to the land. . . ."

The grave is easy to find. The marker is a gray pedestal inscribed DOUTHITT, on top of which stands a six-foot black cylinder with shimmering flecks; on top of that stands a six-foot white angel holding flowers. Flanking this are two knee-high cylinders for husband and wife. The murdered husband's epitaph reads, "God's ways are mysterious. I am not afraid to die but want all those I have wronged to forgive me." Dolly's cylinder has nothing but her name and dates. Three of her children are buried in this patch of ground, all having died young; one is the suicidal Loma. The graves are pocked with the holes left by cicadas when they emerged from their winter's sleep. I hear those insects nearby, singing in the heat.

Cicada photo by Dee Puett

When the mummy's drawing power began to dwindle, Penniman finally handed it over to Bates, who had been claiming it since the beginning. Bates planned to make the mummy a sideshow, but couldn't raise the cash. So he rented it out to other exhibitors, and John Wilkes Booth, or at least his facsimile, was back in show business. The corpse traveled as part of a show featuring lavish live marriages and freak animals. It emerged unscathed from a train wreck that killed eight people, which may have been when it picked up the legend of a Tut-style curse. Tutankhamen had only recently been dug up, and such stories were in vogue. It got kidnapped and ransomed. It was offered to Henry Ford for his museum in Dearborn, Michigan; Ford had the mummy investigated and found its credentials dubious.

By 1931, the mummy had somehow fallen into the possession of a Chicago woman named Agnes Black, who purportedly bought it for $8000. Black, and the Chicago Press Club, arranged for a group of Chicago doctors to perform an autopsy to establish the mummy's authenticity. The doctors, led by Orlando Scott, used Finis Bates's book as a starting point. Bates listed Booth's physical imperfections -- a scar over his right eyebrow, the result of an accident during a stage duel; the left ankle broken in his leap to the stage at Ford's theater; and a deformed right thumb crushed by a piece of stage gear. The thumb injury seems to have been unknown in Booth's life before 1865. Bates apparently found out about it from a woman who claimed to have married yet another post-war Tennessee Booth.

Using gross examination and x-rays, the doctors supposedly found evidence of all three anomalies. An autopsy report signed by half a dozen physicians was issued to the press. The surgical scar on Booth's neck is not mentioned in the report. But it is mentioned in an affidavit signed by two doctors who refused to sign the report. One of these renegade physicians attested that he had used a fluoroscope to look for scar tissue on the mummy's neck--and found none. He said Orlando Scott had asked him to lie about this finding and go along with the "publicity stunt." Dr. Scott told newspapers the x-rays had revealed a metal fragment in the mummy's stomach, which the doctors retrieved by cutting through the mummy's back. The fragment proved to be part of a signet ring bearing the letter B. The autopsy report does not mention the ring.

Booth scholar Blaine Houmes, who is also a physician and a deputy medical examiner, has seen the x-rays. He says they show no sign of a broken leg.

In 1932 a retired carnival performer named Barney Harkin owned the mummy. Harkin had worked as a tattooed man before settling down as a landlord in Chicago. The mummy lured him back. The eccentric Harkin believed Napoleon had escaped after Waterloo and a dummy had been sent to St. Helena in his place. That John Wilkes Booth was for sale in Chicago did not strike him as utterly improbable.

Harkin and his wife Agnes ran their show from a truck in which they slept at night, the mummy bunking between them for safety. Barney handled the gate; Agnes lectured the crowd, showing the Chicago x-rays and turning the mummy to show its shortened left leg. Hecklers sometimes claimed the figure was wax; she silenced them by rolling the mummy on its side and opening a flap in its back that had been cut at the autopsy. The mummy wore nothing but khaki shorts, and between shows Agnes Harkin lacquered its skin with Vaseline and combed its hair, which had gone white since the day David E. George expired with an atrocious dye job decades earlier.

Barney Harkin toured with the mummy into the 1950s. He died a destitute widower in Philadelphia. His landlady seized the mummy in lieu of his unpaid rent. The building where she stored it was demolished, and the mummy's trail since then has been difficult to follow. Scattered reports had sideshows exhibiting the as Booth mummy as recently as the mid-70s, alongside a pickled set of Siamese twins and the car in which Jayne Mansfield was decapitated. All sources seem to agree it's now in the hands of "a private collector," but this person declines to speak with the press.

Ken Hawkes, an autopsy assistant from Memphis, spent a decade searching for the mummy. If he ever finds it, he'd be happy to buy it. But he'd settle for a few clippings and scrapings for testing and maybe a full-body x-ray. That sort of evidence might settle the debate for good. He estimates he has checked out 2,000 leads. He once came across a collector who owned the mummified leg of a victim in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, and other collectors who had complete mummies of 1920s gangsters. One lead pointed to Seattle, where Ye Olde Curiosity Shop exhibits a mummy named Sylvester. Sylvester had indeed worked under the name John Wilkes Booth at one point in his own sideshow career, but old photos of the mummified David E. George make it clear that Sylvester was only a knock-off. Sylvester's true identity has never been established.

Hawkes located several mummies kept in homes. Some of these are relatives of the people they now reside with. According to Hawkes, the publicity surrounding David E. George in the early 1900s created a fad for mummifying relatives with a combination of arsenic and formaldehyde.

Blaine Houmes says the x-ray pictures from 1931 are studded with granules of a heavy metal -- doubtless arsenic. If the mummy still exists, the concentration of arsenic in its tissues makes it a health hazard. The elusive "private collector" may be breathing in death every day, dying of slow poison even as he hoards his immortal emblem.

Four months after my first expedition to Enid, I make another. The town has been invaded by a heat wave and a steer convention. The sign on a bank says 103 and the marquees on the hotels say WELCOME INTERNATIONAL BRANGUS ASSOCIATION. Brangus are a breed of cattle compounded of Brahman and Angus. I go to see the Brangus at the fairgrounds and, though no events are going on at this particular time, I see people in Wranglers and oversized belt buckles grooming their velvety black castratoes. They've been brushed to an exquisite lacquer, like contestants in a beauty pageant. When a steer looks at me it's like gazing back into two cups of black coffee.

I visit the cemetary where lies the body of Dolly Douthitt, the colorful murderer the man at the museum told me about. The trees all around have a curiously ordered appearance, even for a cemetary. After a while I realize why. All of them, pines as well as elms, have been pruned up to about ten feet, so that the whole expanse of the cemetary is visible under a green canopy. Through that canopy I can see hawks wheeling in the clear sky. The tune of the Oklahoma state song, from the Broadway musical, suddenly crawls through my mind: "Sit alone and talk, and watch a hawk makin' lazy circles in the sky. We know we belong to the land. . . ."

The grave is easy to find. The marker is a gray pedestal inscribed DOUTHITT, on top of which stands a six-foot black cylinder with shimmering flecks; on top of that stands a six-foot white angel holding flowers. Flanking this are two knee-high cylinders for husband and wife. The murdered husband's epitaph reads, "God's ways are mysterious. I am not afraid to die but want all those I have wronged to forgive me." Dolly's cylinder has nothing but her name and dates. Three of her children are buried in this patch of ground, all having died young; one is the suicidal Loma. The graves are pocked with the holes left by cicadas when they emerged from their winter's sleep. I hear those insects nearby, singing in the heat.

Cicada photo by Dee Puett

Published on October 04, 2011 09:08

October 3, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 6

Go to the beginning of this story

Like every other part of the legend, George's mummification has been explained in six or eight contradictory ways. One story claims the arsenic with which George killed himself did the job accidentally. The most plausible story comes from the pen of the undertaker, William Broadwell Penniman. It reads like Frankenstein, but, as one commentator noted, with more slapstick. The afternoon of the suicide, Penniman opened George's right carotid artery and inserted an intravenous tube. He did this, he later wrote, "more to keep familiar with the anatomy of this part of the body than with the idea of preserving or disinfecting it." Penniman made a bloody mess of this procedure. A witness fainted.

When Mrs. Harper identified George as Booth, Penniman claims to have issued the smooth reply, "That being the case, I believe I will embalm him and keep him." Penniman made no effort to check Mrs. Harper's information because the Booth story was "cheap advertising," and he didn't want it debunked. When Finis Bates announced his intention of coming from his home in Memphis to see the corpse, Penniman coated it in Vaseline, wrapped it up, and hid it. He would take no chances of Bates being "an irrational Southerner" with designs on the body.

After meeting Bates and hearing his tale of John St. Helen, Penniman seems to have changed his mind. He no longer regarded the Booth yarn as a temporary gimmick for advertising his furniture store. Now he began to see the possibility of real money. Accordingly, he made a further attempt at embalming, injecting a formaldehyde solution into the large arteries in the thighs, apparently in combination with an arsenic compound. "The effect was far from satisfactory," he noted. "Within a few weeks the skin had the drawn and tanned look of an old mummy." It was, Penniman confessed, an unnecessary procedure, which he followed with another. He repeated the embalming so that a salesman who supplied him with embalming chemicals could participate. The salesman, who was allowed to work on the body cavity, thought it would be a good selling point in his business to have embalmed Booth. His company used a photo of George's corpse in a trade journal ad.

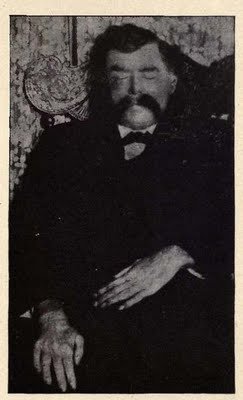

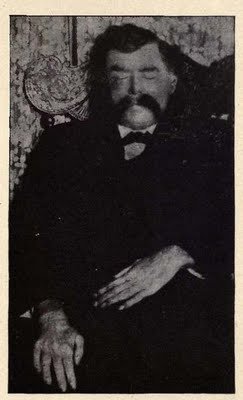

It was Penniman, abetted by Bates, who posed George's corpse with its eyes open and a newspaper spread in its lap. At Bates's suggestion, he combed George's hair to resemble the coif in a tintype of St. Helen. The photograph of George in this position was taken before the "drawn and tanned" look set in; his appearance was still lifelike.

Penniman recruited local boys to work as tour guides. The boys--one of whom was historian Marquis James--would greet people at the train station, telling them the body of Booth could be viewed for a dime. Enid briefly became a tourist stop. Penniman claimed some 10,000 people had viewed the body at his establishment. Penniman made good money with his scheme, but the body suffered. Tourists swiped its collar buttons--more than fifty of them--for souvenirs and took locks of its hair. Once Penniman caught a tourist trying to carve off the corpse's ear with a pocket knife.

Like every other part of the legend, George's mummification has been explained in six or eight contradictory ways. One story claims the arsenic with which George killed himself did the job accidentally. The most plausible story comes from the pen of the undertaker, William Broadwell Penniman. It reads like Frankenstein, but, as one commentator noted, with more slapstick. The afternoon of the suicide, Penniman opened George's right carotid artery and inserted an intravenous tube. He did this, he later wrote, "more to keep familiar with the anatomy of this part of the body than with the idea of preserving or disinfecting it." Penniman made a bloody mess of this procedure. A witness fainted.

When Mrs. Harper identified George as Booth, Penniman claims to have issued the smooth reply, "That being the case, I believe I will embalm him and keep him." Penniman made no effort to check Mrs. Harper's information because the Booth story was "cheap advertising," and he didn't want it debunked. When Finis Bates announced his intention of coming from his home in Memphis to see the corpse, Penniman coated it in Vaseline, wrapped it up, and hid it. He would take no chances of Bates being "an irrational Southerner" with designs on the body.

After meeting Bates and hearing his tale of John St. Helen, Penniman seems to have changed his mind. He no longer regarded the Booth yarn as a temporary gimmick for advertising his furniture store. Now he began to see the possibility of real money. Accordingly, he made a further attempt at embalming, injecting a formaldehyde solution into the large arteries in the thighs, apparently in combination with an arsenic compound. "The effect was far from satisfactory," he noted. "Within a few weeks the skin had the drawn and tanned look of an old mummy." It was, Penniman confessed, an unnecessary procedure, which he followed with another. He repeated the embalming so that a salesman who supplied him with embalming chemicals could participate. The salesman, who was allowed to work on the body cavity, thought it would be a good selling point in his business to have embalmed Booth. His company used a photo of George's corpse in a trade journal ad.

It was Penniman, abetted by Bates, who posed George's corpse with its eyes open and a newspaper spread in its lap. At Bates's suggestion, he combed George's hair to resemble the coif in a tintype of St. Helen. The photograph of George in this position was taken before the "drawn and tanned" look set in; his appearance was still lifelike.

Penniman recruited local boys to work as tour guides. The boys--one of whom was historian Marquis James--would greet people at the train station, telling them the body of Booth could be viewed for a dime. Enid briefly became a tourist stop. Penniman claimed some 10,000 people had viewed the body at his establishment. Penniman made good money with his scheme, but the body suffered. Tourists swiped its collar buttons--more than fifty of them--for souvenirs and took locks of its hair. Once Penniman caught a tourist trying to carve off the corpse's ear with a pocket knife.

In the centre of this singular chamber was a large, square table, littered with papers, bottles, and the dried leaves of some graceful, palm-like plant. These varied objects had all been heaped together in order to make room for a mummy case, which had been conveyed from the wall, as was evident from the gap there, and laid across the front of the table. The mummy itself, a horrid, black, withered thing, like a charred head on a gnarled bush, was lying half out of the case, with its clawlike hand and bony forearm resting upon the table.

Smith stepped over to the table and looked down with a professional eye at the black and twisted form in front of him. The features, though horribly discoloured, were perfect, and two little nut-like eyes still lurked in the depths of the black, hollow sockets. The blotched skin was drawn tightly from bone to bone, and a tangled wrap of black coarse hair fell over the ears. Two thin teeth, like those of a rat, overlay the shrivelled lower lip. In its crouching position, with bent joints and craned head, there was a suggestion of energy about the horrid thing which made Smith's gorge rise. The gaunt ribs, with their parchment-like covering, were exposed, and the sunken, leaden-hued abdomen, with the long slit where the embalmer had left his mark; but the lower limbs were wrapped round with coarse yellow bandages. A number of little clove-like pieces of myrrh and of cassia were sprinkled over the body, and lay scattered on the inside of the case.

The form was lifeless and inert, but it seemed to Smith as he gazed that there still lingered a lurid spark of vitality, some faint sign of consciousness in the little eyes which lurked in the depths of the hollow sockets.

Arthur Conan Doyle

Published on October 03, 2011 09:59

October 2, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 5

Go to the beginning of this story

At the public library in Enid, I approach the man at the desk.

"I'm looking for information on the mummy of--"

He stops me with the weary nod and directs me to the Marquis James Room upstairs. There I find two folders fat with press clippings and photocopied chapters.

One newspaper article reproduces a photo of Booth--one of the most often photographed human beings in that early photographic era. I glance up to a row of photos on the wall--Henry Cessna, the Geronimo automobile, and other such Enid notables. There's David E. George's corpse in a chair with a newspaper spread in its lap. It's the same photo I've seen at Garfield Furniture and the Museum of the Cherokee Strip, but a particularly large and clean print. George's face happens to be turned the same way Booth's is in the photocopy before me. I get a chill, because they look so much alike it's hard not to see them as the same man.

Abraham Lincoln died long before Enid came into being, but the city's folklore is full of connections to the martyred president. Besides Booth, a first cousin of Lincoln's is said to have lived in Enid, and the son of a tutor who worked for the Lincolns settled in the nearby town of Ames. And then there's Boston Corbett, a man whose name is often preceded in popular accounts by the word mad.

Born Thomas H. Corbett in London in 1832, he moved with his parents to New York when he was seven. As a young man, Corbett married and took up a career as a hatter. His wife died in childbirth, and Corbett immersed himself in the Bible and in meditations on sin. His solution to the problem of temptations of the flesh was to castrate himself with a pair of scissors. In 1858, Corbett took the name of the city where he was baptized as his own to commemorate his rebirth.

When the Civil War began, Corbett ardently opposed the South. He hated slavery and thought the South was acting in the service of the devil. He signed up with the 12th New York Regiment.

By 1864 he was a prisoner of war, serving part of his time in Andersonville. That notorious camp starved prisoners to the bone, reducing people to living skeletons like those in German death camps eighty years later. At one point Andersonville produced 100 corpses a day, and scavenging animals defiled the shallow graves at night. At the war's end Andersonville cemetery held 13,000 graves. Corbett didn't have to wait for the end of the war; he returned to the North in a prisoner exchange in November 1864, but his health was broken. After a medical furlough, he returned to duty in what was expected to be a non-combat post, as part of the regiment's headquarters detachment. One of the duties of this detachment was to ride in Lincoln's funeral procession. That was the funeral that made flowers an American death-custom.

Despite their expectation of light duty, Corbett's detachment was sent to pursue Booth. After three days in enemy territory with little food, they found him. Some histories have Corbett shooting Booth against orders in a fit of patriotic fervor, or even in response to a divine command; others portray him as an inside man sent to silence a ringer before he could talk. The truth, according to Corbett biographer Stephen G. Miller, is that the men of the detachment were under no orders to take Booth alive. Corbett fired when Booth raised his pistol to kill another man in Corbett's detachment. Corbett aimed for Booth's arm, but actually inflicted the fatal neck wound.

After the war Corbett spent time in New York City and in Camden, New Jersey. He preached and worked as a hatter, though poor health limited his activities. In 1878 a political connection landed him a job as a doorkeeper for the Kansas state legislature. He continued to preach, becoming a popular speaker across Kansas. His faith was not of the armchair variety; he was perpetually low on funds because he gave his money away to the poor.

Although he was widely regarded as a hero, Corbett received hate mail from Booth supporters. One letter said "nemesis is on your heels" -- it was signed "John Wilkes Booth." Such harassment seems to have changed Corbett. He developed a reputation as a man quick to draw his gun, though he never shot anybody. "He was wound pretty tight," says Miller. One day Corbett went through the state capitol with his pistols drawn, issuing threats to legislators and others who got in his way. No one quite understood the cause of his rage. Having been subdued without any real violence, Corbett was committed to an asylum.

After nearly a decade of incarceration, Corbett made his escape. The inmates were on a nature walk when Corbett slipped away and stole a messenger's pony. He turned up at the house of a friend named Thatcher in Neodesha, Kansas. Thatcher had met Corbett in Andersonville, and later had petitioned for his friend's release from the asylum. He harbored his old comrade several days.

And this is where Corbett's fate, like Booth's, splits in two. One version of history--the "official" one, if there is such a thing--claims Corbett was disgruntled that he had been treated as a madman in the country he had served so well. He vowed to leave the United States forever. Thatcher put him on a train for Mexico, and he was never seen in this country again.

The alternate version has Corbett turning up in Oklahoma around the turn of the century. A man named John Corbit worked as a patent medicine salesman there; his employer believed him to be Boston Corbett. Later, this same snake-oil salesman applied for the pension due to Corbett as a veteran. He was living in Enid in 1902 and 1903; he never offered any comment during the media coverage of David E. George's death in that city. A government investigator denied Corbit's claim on the grounds that he didn't match the description of Corbett--he was, in fact, a head taller. The towering impostor did hard time for fraud.

Another variation has Jesse James poisoning George in Enid. James, who officially died twenty years earlier, is said to have accomplished this feat in his role as leader of a secret cabal of Masons. Yet another version plays on the fact that Corbett escaped the asylum in 1888, the same year Jack the Ripper began his career in London. Both men were violent; both were on record as having a problem with prostitutes. The connection is obvious, at least to some.

At the public library in Enid, I approach the man at the desk.

"I'm looking for information on the mummy of--"

He stops me with the weary nod and directs me to the Marquis James Room upstairs. There I find two folders fat with press clippings and photocopied chapters.

One newspaper article reproduces a photo of Booth--one of the most often photographed human beings in that early photographic era. I glance up to a row of photos on the wall--Henry Cessna, the Geronimo automobile, and other such Enid notables. There's David E. George's corpse in a chair with a newspaper spread in its lap. It's the same photo I've seen at Garfield Furniture and the Museum of the Cherokee Strip, but a particularly large and clean print. George's face happens to be turned the same way Booth's is in the photocopy before me. I get a chill, because they look so much alike it's hard not to see them as the same man.

Richard:

And from that torment I will free myself,

Or hew my way out with a bloody axe.

William Shakespeare

Abraham Lincoln died long before Enid came into being, but the city's folklore is full of connections to the martyred president. Besides Booth, a first cousin of Lincoln's is said to have lived in Enid, and the son of a tutor who worked for the Lincolns settled in the nearby town of Ames. And then there's Boston Corbett, a man whose name is often preceded in popular accounts by the word mad.

Born Thomas H. Corbett in London in 1832, he moved with his parents to New York when he was seven. As a young man, Corbett married and took up a career as a hatter. His wife died in childbirth, and Corbett immersed himself in the Bible and in meditations on sin. His solution to the problem of temptations of the flesh was to castrate himself with a pair of scissors. In 1858, Corbett took the name of the city where he was baptized as his own to commemorate his rebirth.

When the Civil War began, Corbett ardently opposed the South. He hated slavery and thought the South was acting in the service of the devil. He signed up with the 12th New York Regiment.

By 1864 he was a prisoner of war, serving part of his time in Andersonville. That notorious camp starved prisoners to the bone, reducing people to living skeletons like those in German death camps eighty years later. At one point Andersonville produced 100 corpses a day, and scavenging animals defiled the shallow graves at night. At the war's end Andersonville cemetery held 13,000 graves. Corbett didn't have to wait for the end of the war; he returned to the North in a prisoner exchange in November 1864, but his health was broken. After a medical furlough, he returned to duty in what was expected to be a non-combat post, as part of the regiment's headquarters detachment. One of the duties of this detachment was to ride in Lincoln's funeral procession. That was the funeral that made flowers an American death-custom.

Despite their expectation of light duty, Corbett's detachment was sent to pursue Booth. After three days in enemy territory with little food, they found him. Some histories have Corbett shooting Booth against orders in a fit of patriotic fervor, or even in response to a divine command; others portray him as an inside man sent to silence a ringer before he could talk. The truth, according to Corbett biographer Stephen G. Miller, is that the men of the detachment were under no orders to take Booth alive. Corbett fired when Booth raised his pistol to kill another man in Corbett's detachment. Corbett aimed for Booth's arm, but actually inflicted the fatal neck wound.

After the war Corbett spent time in New York City and in Camden, New Jersey. He preached and worked as a hatter, though poor health limited his activities. In 1878 a political connection landed him a job as a doorkeeper for the Kansas state legislature. He continued to preach, becoming a popular speaker across Kansas. His faith was not of the armchair variety; he was perpetually low on funds because he gave his money away to the poor.

Although he was widely regarded as a hero, Corbett received hate mail from Booth supporters. One letter said "nemesis is on your heels" -- it was signed "John Wilkes Booth." Such harassment seems to have changed Corbett. He developed a reputation as a man quick to draw his gun, though he never shot anybody. "He was wound pretty tight," says Miller. One day Corbett went through the state capitol with his pistols drawn, issuing threats to legislators and others who got in his way. No one quite understood the cause of his rage. Having been subdued without any real violence, Corbett was committed to an asylum.

After nearly a decade of incarceration, Corbett made his escape. The inmates were on a nature walk when Corbett slipped away and stole a messenger's pony. He turned up at the house of a friend named Thatcher in Neodesha, Kansas. Thatcher had met Corbett in Andersonville, and later had petitioned for his friend's release from the asylum. He harbored his old comrade several days.

And this is where Corbett's fate, like Booth's, splits in two. One version of history--the "official" one, if there is such a thing--claims Corbett was disgruntled that he had been treated as a madman in the country he had served so well. He vowed to leave the United States forever. Thatcher put him on a train for Mexico, and he was never seen in this country again.

The alternate version has Corbett turning up in Oklahoma around the turn of the century. A man named John Corbit worked as a patent medicine salesman there; his employer believed him to be Boston Corbett. Later, this same snake-oil salesman applied for the pension due to Corbett as a veteran. He was living in Enid in 1902 and 1903; he never offered any comment during the media coverage of David E. George's death in that city. A government investigator denied Corbit's claim on the grounds that he didn't match the description of Corbett--he was, in fact, a head taller. The towering impostor did hard time for fraud.

Another variation has Jesse James poisoning George in Enid. James, who officially died twenty years earlier, is said to have accomplished this feat in his role as leader of a secret cabal of Masons. Yet another version plays on the fact that Corbett escaped the asylum in 1888, the same year Jack the Ripper began his career in London. Both men were violent; both were on record as having a problem with prostitutes. The connection is obvious, at least to some.

Published on October 02, 2011 09:47

October 1, 2011

Death Stories: The George Mummy, Part 4

Go to the beginning of this story

Accounts of John Wilkes Booth's activities after his hypothetical escape from Garrett's tobacco shed are staggering in their variety. Newspapers reported Booth sightings for decades after 1865, sometimes in the tongue-in-cheek spirit familiar to followers of current Elvis encounters. Booth continued his acting career in Brazil under the name Unos; or he escaped to Europe on a steamer. His latter-day job descriptions included schoolteacher, house painter, and buffalo wagon driver. He lived in New Orleans or Atlanta, died in California or Indiana, England or India. "There's a whole slew of them in Mississippi," says author and filmmaker Michael W. Kauffman, who is assembling a documentary on Booth. Kauffman has recorded more than forty claimants to the title of "the real Booth."

In one of Booth's several Tennessee incarnations, a man named John W. Burks sought shelter at the Brigham farm near Erin after the war. He soon won the love of the young lady of the house, a Miss Georgia Brigham, but told her he could not marry because circumstances forced him to live under an assumed name. His wardrobe of velvet suits and silk hats impressed neighbors, as did his apparently ample supply of gold. Burks confessed to being Booth on at least two occasions, and his neighbors believed him to be the legitimate article. He died of typhoid in 1871. Journalist T. H. Alexander, who reported the Burks case in 1932, attributed the credulity of the "romance-starved countryside" to the hard life of Southerners during Reconstruction. Alexander also noted dryly that Burks misspelled "Wilkes" when he autographed a photo for Georgia Brigham.

Granbury, Texas, has its own Booth (and, incidentally, its own Jesse James). John St. Helen came to the Granbury area in the early 1870s. St. Helen was a flamboyant bartender and rogue known for his dapper dress, his courtly manners, and his barroom conversation, which was studded with orations from Shakespeare. When a minor legal matter involving a liquor license required a court appearance, St. Helen, averse to contact with the law, hired an attorney named Finis L. Bates to help him pay his way out of the scrape. In 1872, St. Helen, sick and fearing for his life, allegedly confessed to Bates that he was Booth. St. Helen recovered his health and eventually left the area. In 1898, Bates, having apparently spent years researching the Lincoln assassination, was ready to present his theory of Booth's continued survival to the government. He tried to claim the bounty on Booth by turning in his former client. The soldiers who shot the man in Garrett's tobacco shed had already collected the reward, and Bates was informed the government had "no interest" in the matter. Bates's next gambit was to propose a book exposing St. Helen. No publisher was interested.

Whether St. Helen actually made a confession is a debatable point. Some of his contemporaries said the confession was exactly the sort of thing he might have said to young Bates as a joke. Years earlier, St. Helen had confessed to being a son of Marshall Michel Ney. Ney, a battlefield commander under Napoleon, was the subject of escape legends like those surrounding Booth. Officially executed as a traitor after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, Ney was said to have used his Masonic connections to escape to America, where he lived as a schoolteacher.

When the story of David E. George hit the newspapers in 1903, lawyer Finis Bates appeared in Enid, claiming George was really St. Helen and both were Booth. Despite his earlier efforts to cash in, Bates wept at the sight of George's corpse and called it "my old friend St. Helen." His renewed claims on the bounty were fruitless. His second attempt at a book found a publisher. The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, published in 1907, presents an intricate biography of Booth after Garrett's farm, much of it based on statements St. Helen supposedly made to Bates in Texas.

From the time of David E. George's death, Bates had company--and competition--in his quest to turn George into cash. A woman wrote to Enid claiming to be Booth's daughter by a post-war marriage and inquiring after her legacy. A traveling salesman named in one of George's wills showed up to claim the estate. The trouble was that George seemed to make a will whenever he went on a bender and then forget about it when he sobered up. He also had a habit of willing away property he'd never owned.

At his death, George had precisely two cents in his pocket. Inquiries revealed a further estate worth twelve dollars. The various heirs vanished.

Accounts of John Wilkes Booth's activities after his hypothetical escape from Garrett's tobacco shed are staggering in their variety. Newspapers reported Booth sightings for decades after 1865, sometimes in the tongue-in-cheek spirit familiar to followers of current Elvis encounters. Booth continued his acting career in Brazil under the name Unos; or he escaped to Europe on a steamer. His latter-day job descriptions included schoolteacher, house painter, and buffalo wagon driver. He lived in New Orleans or Atlanta, died in California or Indiana, England or India. "There's a whole slew of them in Mississippi," says author and filmmaker Michael W. Kauffman, who is assembling a documentary on Booth. Kauffman has recorded more than forty claimants to the title of "the real Booth."

In one of Booth's several Tennessee incarnations, a man named John W. Burks sought shelter at the Brigham farm near Erin after the war. He soon won the love of the young lady of the house, a Miss Georgia Brigham, but told her he could not marry because circumstances forced him to live under an assumed name. His wardrobe of velvet suits and silk hats impressed neighbors, as did his apparently ample supply of gold. Burks confessed to being Booth on at least two occasions, and his neighbors believed him to be the legitimate article. He died of typhoid in 1871. Journalist T. H. Alexander, who reported the Burks case in 1932, attributed the credulity of the "romance-starved countryside" to the hard life of Southerners during Reconstruction. Alexander also noted dryly that Burks misspelled "Wilkes" when he autographed a photo for Georgia Brigham.

Men have died from time to --William Shakespeare

Granbury, Texas, has its own Booth (and, incidentally, its own Jesse James). John St. Helen came to the Granbury area in the early 1870s. St. Helen was a flamboyant bartender and rogue known for his dapper dress, his courtly manners, and his barroom conversation, which was studded with orations from Shakespeare. When a minor legal matter involving a liquor license required a court appearance, St. Helen, averse to contact with the law, hired an attorney named Finis L. Bates to help him pay his way out of the scrape. In 1872, St. Helen, sick and fearing for his life, allegedly confessed to Bates that he was Booth. St. Helen recovered his health and eventually left the area. In 1898, Bates, having apparently spent years researching the Lincoln assassination, was ready to present his theory of Booth's continued survival to the government. He tried to claim the bounty on Booth by turning in his former client. The soldiers who shot the man in Garrett's tobacco shed had already collected the reward, and Bates was informed the government had "no interest" in the matter. Bates's next gambit was to propose a book exposing St. Helen. No publisher was interested.

Whether St. Helen actually made a confession is a debatable point. Some of his contemporaries said the confession was exactly the sort of thing he might have said to young Bates as a joke. Years earlier, St. Helen had confessed to being a son of Marshall Michel Ney. Ney, a battlefield commander under Napoleon, was the subject of escape legends like those surrounding Booth. Officially executed as a traitor after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, Ney was said to have used his Masonic connections to escape to America, where he lived as a schoolteacher.

When the story of David E. George hit the newspapers in 1903, lawyer Finis Bates appeared in Enid, claiming George was really St. Helen and both were Booth. Despite his earlier efforts to cash in, Bates wept at the sight of George's corpse and called it "my old friend St. Helen." His renewed claims on the bounty were fruitless. His second attempt at a book found a publisher. The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, published in 1907, presents an intricate biography of Booth after Garrett's farm, much of it based on statements St. Helen supposedly made to Bates in Texas.

From the time of David E. George's death, Bates had company--and competition--in his quest to turn George into cash. A woman wrote to Enid claiming to be Booth's daughter by a post-war marriage and inquiring after her legacy. A traveling salesman named in one of George's wills showed up to claim the estate. The trouble was that George seemed to make a will whenever he went on a bender and then forget about it when he sobered up. He also had a habit of willing away property he'd never owned.

At his death, George had precisely two cents in his pocket. Inquiries revealed a further estate worth twelve dollars. The various heirs vanished.

Voice from the Underworld

from Gilgamesh

Have you seen a man who died in foreign land,

from accident or age?

I have. He sits alone and screams

and tears his fingernails out.

Have you seen a man who died in the wild,

his corpse despoiled by jackals?

I have. He wanders half-clothed

and cannot rest.

Have you seen a man with no kinsmen left

alive to love him?

I have. In the underworld

he eats the cauldron's scrapings,

the food the maggots will not eat.

Published on October 01, 2011 09:31