Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 61

April 13, 2015

The invisibility and nudity ring: vanishing Vinod in a 1971 film called Elaan

[Did a version of this for the Daily O]

With India’s newest Invisible Man film – the Emraan Hashmi-starrer Mr X – about to release, there has been much talk about computer-generated effects, and even more talk about the fondly remembered Mr India . But forget all that. It is time to rescue from film vaults another, older movie that features an invisibility device.

Historically, the 1971

Elaan

has minor importance for being the first ever pairing of Rekha and Vinod Mehra, who were an under-appreciated screen couple. Be warned though: the Rekha and Vinod Mehra in this film are a species or two removed from the same actors in, say,

Ghar

, which was made years later.

Historically, the 1971

Elaan

has minor importance for being the first ever pairing of Rekha and Vinod Mehra, who were an under-appreciated screen couple. Be warned though: the Rekha and Vinod Mehra in this film are a species or two removed from the same actors in, say,

Ghar

, which was made years later.

I’ll skip the preliminaries, such as the grisly courtship scenes between their characters Naresh and Mala (which include him being molested by a tribe of her sahelis at a picnic), and get to the main plot. Naresh – an upwardly mobile journalist – runs afoul of one of those “international” crime syndicates that use high-tech gadgets (blue rotary phones! walkie-talkies! flower pots that can be twisted about to make a door open!) and do unspeakably evil things such as printing literally dozens of fake one-rupee notes and hanging them on a clothes-line to dry. (“Ek din India ki currency fail ho jaayegi aur hum log maalamaal ho jaayenge! Ha. Ha. Ha.”)

"Well, Mrs Gandhi is saying Garibi Hatao."

"Well, Mrs Gandhi is saying Garibi Hatao."

This shot of white-skinned masseuses in floral bikinis, a VAT 69 bottle and a topless Madan Puri, all in the same frame, will reveal their satanic depths.

When you learn that the villains’ main den (“Phase 1”) is on a distant island, that one of the head villains (the ever-reliable Shetty) is bald and that the other head villain is played by Amrish Puri’s brother, dots will start to connect in your head. There is already a pre-echo here of Mr India. Then the invisibility theme makes its appearance. Pay attention now.

Naresh finds himself locked in a cellar with a seemingly crazy old man who claims to have invented an “atomic ring” that can make you disappear. Where is this ring, you ask. It turns out he has kept it safely buried in his thigh for years, waiting for a goodhearted person he can bequeath it to. When Naresh respectfully addresses him as “Baba”, the old savant realises his Bilbo Baggins is here at last; so he tears open his own leg, extricates the ring from its gory hiding place, and tells Naresh:

he has kept it safely buried in his thigh for years, waiting for a goodhearted person he can bequeath it to. When Naresh respectfully addresses him as “Baba”, the old savant realises his Bilbo Baggins is here at last; so he tears open his own leg, extricates the ring from its gory hiding place, and tells Naresh:

“Put this in your mouth, then take off all your clothes, and see what happens.”

(Or words to that effect.) I should mention that there is no disinfectant in this cellar.

Remember this excellent Christopher Walken monologue from Pulp Fiction?

In most invisibility stories, either the device-user disappears fully, along with the clothes he is wearing (Mr India, The Lord of the Rings), or the body disappears but the clothes can still be seen (the 1933 Invisible Man with Claude Rains, the Kevin Bacon-starrer Hollow Man). The science of Elaan is a little more complicated: you have to take off all your clothes if you want to turn invisible – otherwise it won’t work at all.

And it must be done in a pre-specified order.

1) First remove your shirt.

2) Carefully place the atomic ring in your mouth – not like you’re Rajinikanth flicking a cigarette, but like you’re Vinod Mehra ingesting a Hajmola for a TV ad.

3) After this, remove your trousers. (No one ever needs underwear.)

It is only the magical combination of ring-in-mouth PLUS trousers-off that leads to invisibility. Omit one of these important steps and you’re either standing there half-dressed and visible with a ring in your mouth, or naked and visible with a ring in your hand.

Also, the moment your body comes in contact with any sort of cloth – if someone throws a towel over you, for example – all of you becomes visible again.

This is where I present my carefully worked out thesis that Elaan isn’t so much a film about invisibility as a film about the liberating joys of nudity.

No one is too impressed with the invisibility idea to begin with. It is treated as a plot detail, easily jettisoned when other details – such as sleek orange cars – come along. Unlike Mr India and (presumably) Mr X, where so much hinges on this marvelous superpower – and the writers know they can build an adventure around it – Elaan looks at its own script and goes: “Invisibility? Uh-huh. What else you got?”

Consider a scene where Naresh meets Mala, who has joined the CBI after her father is murdered. (It’s that easy. You just join, and get a special number and your own wristwatch-like gizmo, on which CBI boss Iftekhar can call you anytime – and he does, usually at the precise moment when you’re undercover in the villains’ den with bad guys all around you.) She yearns to avenge her daddy; we know this because she is throwing darts at a board with an expression of annoyance, like a picnic has just been cancelled due to rain.

So Naresh gives her the good news straight.

The nakedness, on the other hand, is what really drives this film. Often, when Naresh is being pursued by the bad guys (say, during a breakneck car chase), he has to dump his clothes and vanish. Which means that whenever he wishes to become visible again, he must:

1) find a clothes store,

2) find a shoe store,

3) sneak into each of them by turn,

4) pilfer things in his invisible state without the salesmen noticing anything amiss,

5) wait for a changing room to be unoccupied,

6) enter the changing room,

7) check for CCTV cameras...

See how this sort of thing might slow down the pace of what was intended to be an action movie?

By the film's climax, the dominant mode is low comedy, and people are falling over themselves to get hold of the ring mainly because it gives them an excuse to take off their clothes. After all, what is the point of having both Rajendranath (as Naresh’s buffoonish friend Shyam) and an invisibility-nudity ring in the same film if you can’t use lines like these?

By the film's climax, the dominant mode is low comedy, and people are falling over themselves to get hold of the ring mainly because it gives them an excuse to take off their clothes. After all, what is the point of having both Rajendranath (as Naresh’s buffoonish friend Shyam) and an invisibility-nudity ring in the same film if you can’t use lines like these?

Naresh (having been cornered by the bad guys): “Shyam, apne mooh se ring nikaalo.”

Invisible Shyam: “Par main toh nangaa hoon!”

So Naresh takes off his own coat and puts it around Shyam’s lower half (wisely), and voila, the buffoon reappears.

****

Elaan’s casting was prescient, I feel. After early stints as a hero in B-movies, Vinod Mehra would go on to become one of the invisible men of mainstream Hindi cinema – not so much a second or third lead as a noble foil who always had a brave, rueful smile on his face as if mindful of his place in the pecking order; making up the numbers in multi-hero films like The Burning Train and Jaani Dushman; or appearing as a martyred policeman in the “Pre-Credits Backstory Compression” (to use Rajorshi Chakraborti’s delightful phrase in the piece he wrote for The Popcorn Essayists ) segments of 1980s movies; or stumbling about in a shawl while a bizarre series of opening titles played out.

In Elaan, having got a chance to play hero, he shows terrific screen absence in scenes like these:

Vinod Mehra in an intense romantic moment with Rekha:

Vinod Mehra looking heroic as he rides a motorbike, with Shyam sitting behind him and holding on for dear life.

(Please remember, while looking at the above image, that Naresh is nude. Thank you.)

And here is the closest thing this film has to a special effect:

Twinkle twinkle, fading star

Twinkle twinkle, fading star

No wonder Elaan has remained largely unseen for decades. But you could say that's a pretty good achievement for an invisibility film.

P.S. Among the high points of Elaan is one of those actors who would overshadow Vinod Mehra in the decade to come – the dashing young Vinod Khanna, still in his villain phase.

Managing somehow to look cool even when sitting at a contraption with blinking neon lights and speaking long-distance with his island bosses, Khanna seems to have sky-dropped in from another, classier film. And he gets to be sutradhaar at one point too, with a dialogue that sums up the film’s generally disdainful attitude to invisibility. “Chaalis saal se atomic research ki hai. Ek angoothi banaayi hai jiss se aadmi gaayab ho jaata hai. Wah re, Aladdin ki aulad!” Then he chuckles for a bit and goes back to sleep. As you should too.

film. And he gets to be sutradhaar at one point too, with a dialogue that sums up the film’s generally disdainful attitude to invisibility. “Chaalis saal se atomic research ki hai. Ek angoothi banaayi hai jiss se aadmi gaayab ho jaata hai. Wah re, Aladdin ki aulad!” Then he chuckles for a bit and goes back to sleep. As you should too.

With India’s newest Invisible Man film – the Emraan Hashmi-starrer Mr X – about to release, there has been much talk about computer-generated effects, and even more talk about the fondly remembered Mr India . But forget all that. It is time to rescue from film vaults another, older movie that features an invisibility device.

Historically, the 1971

Elaan

has minor importance for being the first ever pairing of Rekha and Vinod Mehra, who were an under-appreciated screen couple. Be warned though: the Rekha and Vinod Mehra in this film are a species or two removed from the same actors in, say,

Ghar

, which was made years later.

Historically, the 1971

Elaan

has minor importance for being the first ever pairing of Rekha and Vinod Mehra, who were an under-appreciated screen couple. Be warned though: the Rekha and Vinod Mehra in this film are a species or two removed from the same actors in, say,

Ghar

, which was made years later. I’ll skip the preliminaries, such as the grisly courtship scenes between their characters Naresh and Mala (which include him being molested by a tribe of her sahelis at a picnic), and get to the main plot. Naresh – an upwardly mobile journalist – runs afoul of one of those “international” crime syndicates that use high-tech gadgets (blue rotary phones! walkie-talkies! flower pots that can be twisted about to make a door open!) and do unspeakably evil things such as printing literally dozens of fake one-rupee notes and hanging them on a clothes-line to dry. (“Ek din India ki currency fail ho jaayegi aur hum log maalamaal ho jaayenge! Ha. Ha. Ha.”)

"Well, Mrs Gandhi is saying Garibi Hatao."

"Well, Mrs Gandhi is saying Garibi Hatao."This shot of white-skinned masseuses in floral bikinis, a VAT 69 bottle and a topless Madan Puri, all in the same frame, will reveal their satanic depths.

When you learn that the villains’ main den (“Phase 1”) is on a distant island, that one of the head villains (the ever-reliable Shetty) is bald and that the other head villain is played by Amrish Puri’s brother, dots will start to connect in your head. There is already a pre-echo here of Mr India. Then the invisibility theme makes its appearance. Pay attention now.

Naresh finds himself locked in a cellar with a seemingly crazy old man who claims to have invented an “atomic ring” that can make you disappear. Where is this ring, you ask. It turns out

he has kept it safely buried in his thigh for years, waiting for a goodhearted person he can bequeath it to. When Naresh respectfully addresses him as “Baba”, the old savant realises his Bilbo Baggins is here at last; so he tears open his own leg, extricates the ring from its gory hiding place, and tells Naresh:

he has kept it safely buried in his thigh for years, waiting for a goodhearted person he can bequeath it to. When Naresh respectfully addresses him as “Baba”, the old savant realises his Bilbo Baggins is here at last; so he tears open his own leg, extricates the ring from its gory hiding place, and tells Naresh:“Put this in your mouth, then take off all your clothes, and see what happens.”

(Or words to that effect.) I should mention that there is no disinfectant in this cellar.

Remember this excellent Christopher Walken monologue from Pulp Fiction?

This watch. This watch was on your daddy’s wrist when he was shot down over Hanoi. He was captured, put in a Vietnamese prison camp. The way your dad looked at it, that watch was your birthright. So he hid it in the one place he knew he could hide something. His ass. Five long years, he wore this watch up his ass. Then he died of dysentery, he gave me the watch. I hid this uncomfortable hunk of metal up my ass two years. Then, after seven years, I was sent home to my family. And now, little man, I give the watch to you.At least the Walken character didn’t ask little Butch to put the watch in his mouth. No such luck for Naresh.

In most invisibility stories, either the device-user disappears fully, along with the clothes he is wearing (Mr India, The Lord of the Rings), or the body disappears but the clothes can still be seen (the 1933 Invisible Man with Claude Rains, the Kevin Bacon-starrer Hollow Man). The science of Elaan is a little more complicated: you have to take off all your clothes if you want to turn invisible – otherwise it won’t work at all.

And it must be done in a pre-specified order.

1) First remove your shirt.

2) Carefully place the atomic ring in your mouth – not like you’re Rajinikanth flicking a cigarette, but like you’re Vinod Mehra ingesting a Hajmola for a TV ad.

3) After this, remove your trousers. (No one ever needs underwear.)

It is only the magical combination of ring-in-mouth PLUS trousers-off that leads to invisibility. Omit one of these important steps and you’re either standing there half-dressed and visible with a ring in your mouth, or naked and visible with a ring in your hand.

Also, the moment your body comes in contact with any sort of cloth – if someone throws a towel over you, for example – all of you becomes visible again.

This is where I present my carefully worked out thesis that Elaan isn’t so much a film about invisibility as a film about the liberating joys of nudity.

No one is too impressed with the invisibility idea to begin with. It is treated as a plot detail, easily jettisoned when other details – such as sleek orange cars – come along. Unlike Mr India and (presumably) Mr X, where so much hinges on this marvelous superpower – and the writers know they can build an adventure around it – Elaan looks at its own script and goes: “Invisibility? Uh-huh. What else you got?”

Consider a scene where Naresh meets Mala, who has joined the CBI after her father is murdered. (It’s that easy. You just join, and get a special number and your own wristwatch-like gizmo, on which CBI boss Iftekhar can call you anytime – and he does, usually at the precise moment when you’re undercover in the villains’ den with bad guys all around you.) She yearns to avenge her daddy; we know this because she is throwing darts at a board with an expression of annoyance, like a picnic has just been cancelled due to rain.

So Naresh gives her the good news straight.

“Mere paas atomic ring hai!”(Mala titters, like she has heard that the weather will improve in the evening. The background music is soft and romantic and not at all conducive to conversations about atoms and protons. So they talk about things more exciting than invisibility, such as where to go for dinner.)

“Atomic ring? Woh kis kaam ka hai?”

“Usse mooh mein rakhne se aadmi gaayab ho jaata hai. Iss se hamara mission aur bhi aasaan ho jaayega.”

The nakedness, on the other hand, is what really drives this film. Often, when Naresh is being pursued by the bad guys (say, during a breakneck car chase), he has to dump his clothes and vanish. Which means that whenever he wishes to become visible again, he must:

1) find a clothes store,

2) find a shoe store,

3) sneak into each of them by turn,

4) pilfer things in his invisible state without the salesmen noticing anything amiss,

5) wait for a changing room to be unoccupied,

6) enter the changing room,

7) check for CCTV cameras...

See how this sort of thing might slow down the pace of what was intended to be an action movie?

By the film's climax, the dominant mode is low comedy, and people are falling over themselves to get hold of the ring mainly because it gives them an excuse to take off their clothes. After all, what is the point of having both Rajendranath (as Naresh’s buffoonish friend Shyam) and an invisibility-nudity ring in the same film if you can’t use lines like these?

By the film's climax, the dominant mode is low comedy, and people are falling over themselves to get hold of the ring mainly because it gives them an excuse to take off their clothes. After all, what is the point of having both Rajendranath (as Naresh’s buffoonish friend Shyam) and an invisibility-nudity ring in the same film if you can’t use lines like these?Naresh (having been cornered by the bad guys): “Shyam, apne mooh se ring nikaalo.”

Invisible Shyam: “Par main toh nangaa hoon!”

So Naresh takes off his own coat and puts it around Shyam’s lower half (wisely), and voila, the buffoon reappears.

****

Elaan’s casting was prescient, I feel. After early stints as a hero in B-movies, Vinod Mehra would go on to become one of the invisible men of mainstream Hindi cinema – not so much a second or third lead as a noble foil who always had a brave, rueful smile on his face as if mindful of his place in the pecking order; making up the numbers in multi-hero films like The Burning Train and Jaani Dushman; or appearing as a martyred policeman in the “Pre-Credits Backstory Compression” (to use Rajorshi Chakraborti’s delightful phrase in the piece he wrote for The Popcorn Essayists ) segments of 1980s movies; or stumbling about in a shawl while a bizarre series of opening titles played out.

In Elaan, having got a chance to play hero, he shows terrific screen absence in scenes like these:

Vinod Mehra in an intense romantic moment with Rekha:

Vinod Mehra looking heroic as he rides a motorbike, with Shyam sitting behind him and holding on for dear life.

(Please remember, while looking at the above image, that Naresh is nude. Thank you.)

And here is the closest thing this film has to a special effect:

Twinkle twinkle, fading star

Twinkle twinkle, fading starNo wonder Elaan has remained largely unseen for decades. But you could say that's a pretty good achievement for an invisibility film.

P.S. Among the high points of Elaan is one of those actors who would overshadow Vinod Mehra in the decade to come – the dashing young Vinod Khanna, still in his villain phase.

Managing somehow to look cool even when sitting at a contraption with blinking neon lights and speaking long-distance with his island bosses, Khanna seems to have sky-dropped in from another, classier

film. And he gets to be sutradhaar at one point too, with a dialogue that sums up the film’s generally disdainful attitude to invisibility. “Chaalis saal se atomic research ki hai. Ek angoothi banaayi hai jiss se aadmi gaayab ho jaata hai. Wah re, Aladdin ki aulad!” Then he chuckles for a bit and goes back to sleep. As you should too.

film. And he gets to be sutradhaar at one point too, with a dialogue that sums up the film’s generally disdainful attitude to invisibility. “Chaalis saal se atomic research ki hai. Ek angoothi banaayi hai jiss se aadmi gaayab ho jaata hai. Wah re, Aladdin ki aulad!” Then he chuckles for a bit and goes back to sleep. As you should too.

Published on April 13, 2015 02:44

April 5, 2015

A story about movie-watching spaces in Delhi

[From the archives, a piece about film-watching spaces in Delhi: I did this for Outlook’s City Limits magazine in 2007, and had forgotten all about it – remembered it while reading Ziya Us Salam’s book Delhi: 4 Shows, which I reviewed here. Naturally many things in this piece are now dated - and there have been many subsequent developments, such as the lovely screening hall at the Hauz Khas Village restaurant Iron Curtain (now sadly closed). But am putting it here anyway, as a sort of "extra" for the book review]

----------

It’s probably just my south Delhi chauvinism, I think, trying to make sense of the shock and awe I’ve been feeling after a tour of the Delite theatre. Walking into this unimpressive-looking building in (what I think of as) a less-than-happening part of the capital, near Daryaganj, I imagined it would be the regular stand-alone cinema hall: strictly functional, torn leather seats, a few wall fans shuddering valiantly inside a discoloured auditorium. Half an hour later, I left convinced I had seen the plushest movie theatre in the NCR.

Shashank Raizada, whose family has owned Delite since it was opened in 1954, says revamping the once-decrepit hall was high on his priority list. “I wanted the interiors to be five-star hotel quality,” he says, and this isn’t just talk: over Rs 8 crore went into renovating the old 980-capacity hall as well as inaugurating a new 148-seater, and when Delite reopened late last year, it had brocade-fabric seats, Eqyptian carpets, fancy woodwork and a hand-painted dome. Perfume dispensers line the auditorium walls and even the restrooms have a waiting area with lounge seating and expensive enameled glass on the doors.

“People usually want to cut costs in space utilisation,” says Raizada, perhaps cocking a snook at multiplexes that cramp their available space with as many halls as possible. “But a good theatre experience must give the impression of largeness and space.”

Delite is a fine surprise, but it’s also an anomaly: much as I’d love to report that the city is dotted with similarly revamped cinema halls just waiting to be discovered by the multiplex-sated, the real picture is much drabber. The story of the single-screen hall in Delhi continues to be one of missed opportunities, indifferent management, lack of funds and initiative. As Siddheshwar Dayal, former managing partner, Regal (one of the central Delhi halls that is still chugging along, but only just), puts it: “Many of the older theatres don’t have new machinery, Dolby sound or comfortable chairs. There is no real future for them unless they get their act together.”

In fact, it doesn’t take long for me to return to earth with a bump – or several bumps, along Old Delhi’s broken roads. A 15-minute auto ride brings me to the theatre known as “Moti Talkies”, located somewhere between the Red Fort and Town Hall, and it’s here that one gets a sense of how the movie-viewing culture in this part of Delhi has faded. Moti, one of the very few theatres still open in the old city, is now a haven for Bhojpuri-film lovers – the manager, V K Garg, denies this, claiming half-heartedly that “we still sometimes show the new Hindi releases”, but the posters on the wall outside tell a different story. The cheaply made movies shown here have titles borrowed from old Hindi films -- Ram Balram, Chacha Bhatija -- and such evocative taglines as “Tu hui daal-bhaat chokha, hum hai aam ke aachar” (the flavour of this line is lost in translation, so don’t ask for one) printed on pictures of buxom heroines, street-Romeo heroes trying to look cool in shades, and leering policemen twirling phallic batons. It’s a world very far removed from that inhabited by the spoilt urban youngsters who go to New Delhi’s air-conditioned malls.

In fact, it doesn’t take long for me to return to earth with a bump – or several bumps, along Old Delhi’s broken roads. A 15-minute auto ride brings me to the theatre known as “Moti Talkies”, located somewhere between the Red Fort and Town Hall, and it’s here that one gets a sense of how the movie-viewing culture in this part of Delhi has faded. Moti, one of the very few theatres still open in the old city, is now a haven for Bhojpuri-film lovers – the manager, V K Garg, denies this, claiming half-heartedly that “we still sometimes show the new Hindi releases”, but the posters on the wall outside tell a different story. The cheaply made movies shown here have titles borrowed from old Hindi films -- Ram Balram, Chacha Bhatija -- and such evocative taglines as “Tu hui daal-bhaat chokha, hum hai aam ke aachar” (the flavour of this line is lost in translation, so don’t ask for one) printed on pictures of buxom heroines, street-Romeo heroes trying to look cool in shades, and leering policemen twirling phallic batons. It’s a world very far removed from that inhabited by the spoilt urban youngsters who go to New Delhi’s air-conditioned malls.

“Most halls in Old Delhi are on rent, not under proprietorship,” explains Garg, “and the managers don’t have the motivation or the money to revamp them.” Besides, he says, with the commercialisation of Chandni Chowk, local families have stopped coming to watch films together. “Now it’s mostly people from the labour class who drop by once in a while, and they are okay with watching a film while sitting on the steps or standing near the door. There is no real demand for these halls to be revamped.”

The trajectory of movie-watching in the capital has seen many twists and turns since the VCR (that’s “video-cassette recorder”, for anyone born post-1990) era began 30 years ago. For several years after the magic box entered our homes, most respectable middle-class families stayed away from local theatres – initiating a cycle that saw movie-halls get increasingly decrepit, careless about maintenance, and oriented towards patrons of morning shows. On a personal note, in the first ten years of my stay in Saket, I had no idea what the interior of the Anupam hall – a stone’s throw from our house – looked like. We excitedly awaited Fridays back then too, but till the mid-1990s “new-release day” was, for a whole stratum of Delhiites, synonymous with running to the local video library and renting a cassette.

Then, in early 1997, news arrived of this wondrous new thing called the multiplex, a theatre with untold luxuries and three or four separate screens, and shortly afterwards the capital’s first PVR opened in Saket. We gaped at the sofa-chairs and the carpeted softness of the floors, knowing that movie-watching would never be the same again.

Ten years later, with the perpetuation of the mall culture across the NCR, the multiplex – once a symbol of privilege – has become the mainstream option for Delhi’s filmgoers. So does the single-screen theatre still have a future? Sanjeev Bijli, joint MD, PVR Cinemas, thinks it does, but adds a qualifier. “The number of seats has to be manageable, preferably not more than 400 or so,” he says. PVR Cinemas made its first forays into single-screen territory by renovating two old Connaught Place theatres, Plaza and Rivoli, but these have seating capacities of only 300 and 330 respectively.

“These days,” says Bijli, “it’s difficult to fill a single-screen theatre that has a large number of seats.” This makes sense if you cast a glance around. Despite the claim made by Delite’s management that the bulk of its audience are oasis-seekers from Old Delhi who have few other options for a classy movie-watching experience, the theatre’s occupancy rates are just a little over 60 per cent – a very good figure by industry standards, but hardly indicative of hordes of entertainment-starved customers streaming in every day.

The viability of PVR Plaza and PVR Rivoli, as Bijli points out, also has to do with extraneous factors, such as the location, the convenience of a nearby Metro station, and the popular Piccadelhi food court at Plaza. “All these things are essential to the success of a movie theatre – and even then, the number of tickets sold will ultimately vary from week to week, depending on the film being shown. On the whole, we still believe the future lies in multiplexes that are located in malls, with lots of shopping and eating options in the immediate vicinity, and where, if you miss the 12 o’clock show, you don’t have to wait for three hours for the next one.”

*****

For some validation of the single-screen experience, I return to Chanakya, a hall that holds special memories for many people of my generation; it was one of only two theatres in New Delhi (the other being Priya in Vasant Vihar) that had an air of respectability in the years just before the multiplex explosion. Walking into the lobby, I find that almost nothing has changed since my last visit nearly a decade ago. The decent, middle-rung cafeteria looks the same – passably clean but nothing that would inspire a health board to dole out medals – and the auditorium is a throwback to a time when we knew nothing about cushioned seats; when the point of the movie-watching experience was the movie, not the ambience or the comfort level.

Theatre manager Ajay Verma is optimistic. “Chanakya has a strong nostalgia value for many old-timers,” he says, “and besides it’s a big screen – many people like sitting in a 1,070-capacity auditorium better than the small halls in multiplexes, which don’t give you the sense of a special experience.” It’s a brave claim, but you can see the cracks in the façade, especially when you peep into this 1,000-plus seater on a Saturday evening and find that it’s only about half full.

Ultimately, the success of a cinema hall depends on a combination of many factors (not least the drawing quotient of the film), but it’s safe to say that providing basic customer satisfaction still takes you a long way. “We think of ourselves as being in the hospitality business, where making customers feel special is very important,” says R K Mehrotra, general manager, Delite Theatre, recalling a time when he and his family had to wait in heavy rain outside a multiplex entrance because no one was being allowed in until 10 minutes before the show. “At our theatre, if you buy the balcony tickets (priced at Rs 85, half of what you’d pay for a weekend show at some halls), you can sit inside the cafeteria for hours before the show begins.”

If other single-screen halls in the capital would take similar initiatives, we’d probably have more options, at better prices. Even the most spoilt movie-goers aren’t such a demanding lot – most of us could comfortably do without the fancy chandeliers Raizada has imported from the Czech Republic – but clean washrooms are always welcome.

------------------

BOX 1: La Dolce Vita

If you decide to indulge yourself at PVR Cinemas’ Gold Class – and you should, even if the bank account won’t allow more than a single visit – make sure to go for a film that’s at least three-and-a-half hours long; you’ll want to spend as much time as possible in this 36-seater auditorium, the movie-hall equivalent of an airline’s Business Class. Most connoisseurs of the good life won’t look beyond the sinfully comfortable Lazy Boy chairs, which can recline to 180 degrees (and which come with blankets), but you can also indulge your fine-dining tastes by ordering a meal from your seat – the menu includes the regular popcorn-and-hot-dog fare as well as more substantial food from the adjoining restaurant. A tip: around five minutes before the film ends, start willing your legs to move around – it’ll take that much time for the brain-to-muscle signals to process.

Picture taken from Mayank Austen Soofi's

Picture taken from Mayank Austen Soofi's

website The Delhi Walla

BOX 2: Delite delicacies

When Shashank Raizada, managing director, Delite, told me about their famous maha-samosas, “the best in town”, I treated it as PR talk. Ten minutes later, munching into one of these monsters in the cafeteria, I was converted. Its impressive size apart, the samosa is fantastic – crisp and firm on the outside, soft, warm and generously filled on the inside – and, at just Rs 20, makes for a decent lunch by itself if you’re not ravenously hungry. The tidy 120-seater cafeteria also has a chuski-maker and a French Fries machine, both of which boast products that are “untouched by hand”, and of course the regular eats and drinks – priced lower than at most multiplexes.

BOX 3

The idea that Delhi doesn’t have a cultural scene is still surprisingly common, and utter hogwash. There are (and have been, for a long time) many options for those interested in films outside of Hindi cinema and Hollywood. Most embassies and cultural centres, for instance, have regular screenings in their (admittedly small) auditoria, and membership is either free or available at very nominal rates. Among the most active are the French Cultural Centre and the Italian Embassy, which have shown films every week (on Fridays and Wednesdays respectively) for as long as I can remember.

Another popular club is the one at the India Habitat Centre, which has a film discussion group, an annual film appreciation course and screens a number of films every month, mostly at the spacious Stein Auditorium. (Membership and contact details: http://www.habitatfilmclub.com/) The film club at Sarai in Civil Lines doesn’t do screenings as often as they used to (every Friday), but there is still some interesting activity here on the movie front, including documentaries and mini-festivals.

The 370-seater Shakuntalam Theatre at Pragati Maidan is an example of a hall that has had to compromise slightly in order to sell tickets. My earliest memory of it is a screening of a 1931 German classic – Fritz Lang’s M – at a film festival years ago, but since then the hall has become more mainstream – a pragmatic decision, given its central location. With tickets priced at Rs 65, this is now a goodish alternative to the commercial theatres. The interiors aren’t too bad – leather seats, wall fans that look suspiciously like regular ceiling fans but which are effective nonetheless. “We are in the process of changing the seats to make them more comfortable,” says Safdar H Khan, senior general manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation (ITPO), which runs the hall. “We’re also bringing in the UFO system, which will allow us to screen the films by satellite from Mumbai instead of by projector.”

----------

It’s probably just my south Delhi chauvinism, I think, trying to make sense of the shock and awe I’ve been feeling after a tour of the Delite theatre. Walking into this unimpressive-looking building in (what I think of as) a less-than-happening part of the capital, near Daryaganj, I imagined it would be the regular stand-alone cinema hall: strictly functional, torn leather seats, a few wall fans shuddering valiantly inside a discoloured auditorium. Half an hour later, I left convinced I had seen the plushest movie theatre in the NCR.

Shashank Raizada, whose family has owned Delite since it was opened in 1954, says revamping the once-decrepit hall was high on his priority list. “I wanted the interiors to be five-star hotel quality,” he says, and this isn’t just talk: over Rs 8 crore went into renovating the old 980-capacity hall as well as inaugurating a new 148-seater, and when Delite reopened late last year, it had brocade-fabric seats, Eqyptian carpets, fancy woodwork and a hand-painted dome. Perfume dispensers line the auditorium walls and even the restrooms have a waiting area with lounge seating and expensive enameled glass on the doors.

“People usually want to cut costs in space utilisation,” says Raizada, perhaps cocking a snook at multiplexes that cramp their available space with as many halls as possible. “But a good theatre experience must give the impression of largeness and space.”

Delite is a fine surprise, but it’s also an anomaly: much as I’d love to report that the city is dotted with similarly revamped cinema halls just waiting to be discovered by the multiplex-sated, the real picture is much drabber. The story of the single-screen hall in Delhi continues to be one of missed opportunities, indifferent management, lack of funds and initiative. As Siddheshwar Dayal, former managing partner, Regal (one of the central Delhi halls that is still chugging along, but only just), puts it: “Many of the older theatres don’t have new machinery, Dolby sound or comfortable chairs. There is no real future for them unless they get their act together.”

In fact, it doesn’t take long for me to return to earth with a bump – or several bumps, along Old Delhi’s broken roads. A 15-minute auto ride brings me to the theatre known as “Moti Talkies”, located somewhere between the Red Fort and Town Hall, and it’s here that one gets a sense of how the movie-viewing culture in this part of Delhi has faded. Moti, one of the very few theatres still open in the old city, is now a haven for Bhojpuri-film lovers – the manager, V K Garg, denies this, claiming half-heartedly that “we still sometimes show the new Hindi releases”, but the posters on the wall outside tell a different story. The cheaply made movies shown here have titles borrowed from old Hindi films -- Ram Balram, Chacha Bhatija -- and such evocative taglines as “Tu hui daal-bhaat chokha, hum hai aam ke aachar” (the flavour of this line is lost in translation, so don’t ask for one) printed on pictures of buxom heroines, street-Romeo heroes trying to look cool in shades, and leering policemen twirling phallic batons. It’s a world very far removed from that inhabited by the spoilt urban youngsters who go to New Delhi’s air-conditioned malls.

In fact, it doesn’t take long for me to return to earth with a bump – or several bumps, along Old Delhi’s broken roads. A 15-minute auto ride brings me to the theatre known as “Moti Talkies”, located somewhere between the Red Fort and Town Hall, and it’s here that one gets a sense of how the movie-viewing culture in this part of Delhi has faded. Moti, one of the very few theatres still open in the old city, is now a haven for Bhojpuri-film lovers – the manager, V K Garg, denies this, claiming half-heartedly that “we still sometimes show the new Hindi releases”, but the posters on the wall outside tell a different story. The cheaply made movies shown here have titles borrowed from old Hindi films -- Ram Balram, Chacha Bhatija -- and such evocative taglines as “Tu hui daal-bhaat chokha, hum hai aam ke aachar” (the flavour of this line is lost in translation, so don’t ask for one) printed on pictures of buxom heroines, street-Romeo heroes trying to look cool in shades, and leering policemen twirling phallic batons. It’s a world very far removed from that inhabited by the spoilt urban youngsters who go to New Delhi’s air-conditioned malls.“Most halls in Old Delhi are on rent, not under proprietorship,” explains Garg, “and the managers don’t have the motivation or the money to revamp them.” Besides, he says, with the commercialisation of Chandni Chowk, local families have stopped coming to watch films together. “Now it’s mostly people from the labour class who drop by once in a while, and they are okay with watching a film while sitting on the steps or standing near the door. There is no real demand for these halls to be revamped.”

The trajectory of movie-watching in the capital has seen many twists and turns since the VCR (that’s “video-cassette recorder”, for anyone born post-1990) era began 30 years ago. For several years after the magic box entered our homes, most respectable middle-class families stayed away from local theatres – initiating a cycle that saw movie-halls get increasingly decrepit, careless about maintenance, and oriented towards patrons of morning shows. On a personal note, in the first ten years of my stay in Saket, I had no idea what the interior of the Anupam hall – a stone’s throw from our house – looked like. We excitedly awaited Fridays back then too, but till the mid-1990s “new-release day” was, for a whole stratum of Delhiites, synonymous with running to the local video library and renting a cassette.

Then, in early 1997, news arrived of this wondrous new thing called the multiplex, a theatre with untold luxuries and three or four separate screens, and shortly afterwards the capital’s first PVR opened in Saket. We gaped at the sofa-chairs and the carpeted softness of the floors, knowing that movie-watching would never be the same again.

Ten years later, with the perpetuation of the mall culture across the NCR, the multiplex – once a symbol of privilege – has become the mainstream option for Delhi’s filmgoers. So does the single-screen theatre still have a future? Sanjeev Bijli, joint MD, PVR Cinemas, thinks it does, but adds a qualifier. “The number of seats has to be manageable, preferably not more than 400 or so,” he says. PVR Cinemas made its first forays into single-screen territory by renovating two old Connaught Place theatres, Plaza and Rivoli, but these have seating capacities of only 300 and 330 respectively.

“These days,” says Bijli, “it’s difficult to fill a single-screen theatre that has a large number of seats.” This makes sense if you cast a glance around. Despite the claim made by Delite’s management that the bulk of its audience are oasis-seekers from Old Delhi who have few other options for a classy movie-watching experience, the theatre’s occupancy rates are just a little over 60 per cent – a very good figure by industry standards, but hardly indicative of hordes of entertainment-starved customers streaming in every day.

The viability of PVR Plaza and PVR Rivoli, as Bijli points out, also has to do with extraneous factors, such as the location, the convenience of a nearby Metro station, and the popular Piccadelhi food court at Plaza. “All these things are essential to the success of a movie theatre – and even then, the number of tickets sold will ultimately vary from week to week, depending on the film being shown. On the whole, we still believe the future lies in multiplexes that are located in malls, with lots of shopping and eating options in the immediate vicinity, and where, if you miss the 12 o’clock show, you don’t have to wait for three hours for the next one.”

*****

For some validation of the single-screen experience, I return to Chanakya, a hall that holds special memories for many people of my generation; it was one of only two theatres in New Delhi (the other being Priya in Vasant Vihar) that had an air of respectability in the years just before the multiplex explosion. Walking into the lobby, I find that almost nothing has changed since my last visit nearly a decade ago. The decent, middle-rung cafeteria looks the same – passably clean but nothing that would inspire a health board to dole out medals – and the auditorium is a throwback to a time when we knew nothing about cushioned seats; when the point of the movie-watching experience was the movie, not the ambience or the comfort level.

Theatre manager Ajay Verma is optimistic. “Chanakya has a strong nostalgia value for many old-timers,” he says, “and besides it’s a big screen – many people like sitting in a 1,070-capacity auditorium better than the small halls in multiplexes, which don’t give you the sense of a special experience.” It’s a brave claim, but you can see the cracks in the façade, especially when you peep into this 1,000-plus seater on a Saturday evening and find that it’s only about half full.

Ultimately, the success of a cinema hall depends on a combination of many factors (not least the drawing quotient of the film), but it’s safe to say that providing basic customer satisfaction still takes you a long way. “We think of ourselves as being in the hospitality business, where making customers feel special is very important,” says R K Mehrotra, general manager, Delite Theatre, recalling a time when he and his family had to wait in heavy rain outside a multiplex entrance because no one was being allowed in until 10 minutes before the show. “At our theatre, if you buy the balcony tickets (priced at Rs 85, half of what you’d pay for a weekend show at some halls), you can sit inside the cafeteria for hours before the show begins.”

If other single-screen halls in the capital would take similar initiatives, we’d probably have more options, at better prices. Even the most spoilt movie-goers aren’t such a demanding lot – most of us could comfortably do without the fancy chandeliers Raizada has imported from the Czech Republic – but clean washrooms are always welcome.

------------------

BOX 1: La Dolce Vita

If you decide to indulge yourself at PVR Cinemas’ Gold Class – and you should, even if the bank account won’t allow more than a single visit – make sure to go for a film that’s at least three-and-a-half hours long; you’ll want to spend as much time as possible in this 36-seater auditorium, the movie-hall equivalent of an airline’s Business Class. Most connoisseurs of the good life won’t look beyond the sinfully comfortable Lazy Boy chairs, which can recline to 180 degrees (and which come with blankets), but you can also indulge your fine-dining tastes by ordering a meal from your seat – the menu includes the regular popcorn-and-hot-dog fare as well as more substantial food from the adjoining restaurant. A tip: around five minutes before the film ends, start willing your legs to move around – it’ll take that much time for the brain-to-muscle signals to process.

Picture taken from Mayank Austen Soofi's

Picture taken from Mayank Austen Soofi's website The Delhi Walla

BOX 2: Delite delicacies

When Shashank Raizada, managing director, Delite, told me about their famous maha-samosas, “the best in town”, I treated it as PR talk. Ten minutes later, munching into one of these monsters in the cafeteria, I was converted. Its impressive size apart, the samosa is fantastic – crisp and firm on the outside, soft, warm and generously filled on the inside – and, at just Rs 20, makes for a decent lunch by itself if you’re not ravenously hungry. The tidy 120-seater cafeteria also has a chuski-maker and a French Fries machine, both of which boast products that are “untouched by hand”, and of course the regular eats and drinks – priced lower than at most multiplexes.

BOX 3

The idea that Delhi doesn’t have a cultural scene is still surprisingly common, and utter hogwash. There are (and have been, for a long time) many options for those interested in films outside of Hindi cinema and Hollywood. Most embassies and cultural centres, for instance, have regular screenings in their (admittedly small) auditoria, and membership is either free or available at very nominal rates. Among the most active are the French Cultural Centre and the Italian Embassy, which have shown films every week (on Fridays and Wednesdays respectively) for as long as I can remember.

Another popular club is the one at the India Habitat Centre, which has a film discussion group, an annual film appreciation course and screens a number of films every month, mostly at the spacious Stein Auditorium. (Membership and contact details: http://www.habitatfilmclub.com/) The film club at Sarai in Civil Lines doesn’t do screenings as often as they used to (every Friday), but there is still some interesting activity here on the movie front, including documentaries and mini-festivals.

The 370-seater Shakuntalam Theatre at Pragati Maidan is an example of a hall that has had to compromise slightly in order to sell tickets. My earliest memory of it is a screening of a 1931 German classic – Fritz Lang’s M – at a film festival years ago, but since then the hall has become more mainstream – a pragmatic decision, given its central location. With tickets priced at Rs 65, this is now a goodish alternative to the commercial theatres. The interiors aren’t too bad – leather seats, wall fans that look suspiciously like regular ceiling fans but which are effective nonetheless. “We are in the process of changing the seats to make them more comfortable,” says Safdar H Khan, senior general manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation (ITPO), which runs the hall. “We’re also bringing in the UFO system, which will allow us to screen the films by satellite from Mumbai instead of by projector.”

Published on April 05, 2015 01:40

April 4, 2015

Todd Stadtman and the 'funky' Indian films of the 1970s

[Did this review for Open magazine]

When I heard an American had written a book about the “funky” Hindi cinema of the 70s, my first reaction was a proprietary sense of unease. Something like the emotion that (I am told) my Bengali friends experience when I, a mere north Indian, have the temerity to discuss Satyajit Ray’s or Ritwik Ghatak’s cinema even though some of the cultural and lingual nuances are beyond my grasp (and the DVD subtitling is often terrible anyway).

Which is to say that even before opening Todd Stadtman’s Funky Bollywood: The Wild World of 1970s Indian Action Cinema , I was readying to roll my eyes at a bit of analysis that “didn’t get it”, condescension directed towards movies I thought highly of – or, just as bad, an undiscerning celebration of mediocrity just because of its perceived kitsch value. If these movies have to be celebrated or trashed, it’s people like me who should do it, I muttered to myself – not someone who didn’t grow up with them and has never even lived in India. I pictured Stadtman as Bob Christo in the climactic fight scene of Disco Dancer, and myself as Mithun laying a bit of the old dhishoom-dhishoom on this firangi noggin while Helen, escorted by dancers in black-face, cavorted about us in a peacock-feather outfit, and we all dodged around a pool containing smoky pink acid and plastic sharks.

However, this defensive nervousness about Stadtman’s book faded once I began reading it. It’s true that he was drawn to 1970s Hindi cinema by its colourful over-the-topness, and that his publishers have had fun with glitzy photos and trivia boxes (e.g. the sequence of images showing a mini-skirted Jeetendra transforming into a snake in Nagin while Sunil Dutt, rifle in hand, stands by stoically) – but this is not in essence a frivolous book hurriedly thrown together to capitalize on a market for corn and cheese. Stadtman has put thought into it. He writes with affection, and with the ambivalence that often makes this sort of writing so compelling – where one gets the sense that the author is struggling with his own responses to a film. Fans of pop culture that tends to get labeled “trash” (or “great trash”, to use Pauline Kael’s simplistic formulation for movies she loved but couldn’t think of as having artistic merit) will know the feeling.

to capitalize on a market for corn and cheese. Stadtman has put thought into it. He writes with affection, and with the ambivalence that often makes this sort of writing so compelling – where one gets the sense that the author is struggling with his own responses to a film. Fans of pop culture that tends to get labeled “trash” (or “great trash”, to use Pauline Kael’s simplistic formulation for movies she loved but couldn’t think of as having artistic merit) will know the feeling.

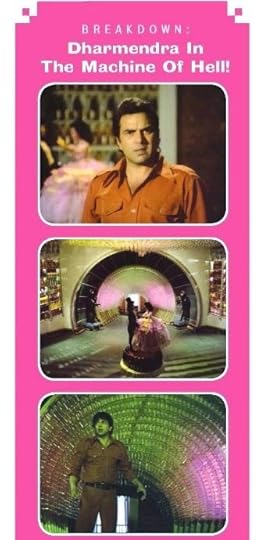

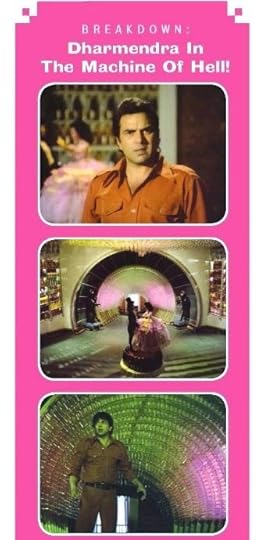

Stadtman is hardly the first non-Indian writer to have developed a strong kinship with Hindi cinema. Other such fans – such as the bloggers Beth Watkins, Greta Kaemmer, Mike Enright and Carla Miriam Levy – all have their own stories about how they became interested in these films. In his introduction Stadtman explains that as a longtime cult-movie enthusiast, he came to 1970s Bollywood after having been through the Mexican lucha libre filmography as well as Turkish superhero mash-ups: he was seeking “speed, violence and garish style […] but cloaked in a cultural context that makes it all seem somehow fresh and new again”. Given this brief, and the glut of eye-popping material that mainstream Hindi films provided him, he might easily have constructed the whole book around tongue-in-cheek descriptions of costumes, props and villains’ lairs – such as this one from his account of the 1978 Azaad:

Stadtman casts his net wide, writing about those cornerstones of the Bachchan era, Zanjeer, Deewaar and Amar Akbar Anthony, as well as a much less seen Amitabh film, the Deven Varma-directed Besharam; stylish, big-budget epics such as BR Chopra’s The Burning Train and Feroz Khan’s Qurbani, as well as films with more modest ambitions such as the Shashi Kapoor-starrers Chor Machaye Shor and Fakira. Some of the inclusions can readily be identified as cult B-movies – Gunmaster G9: Surakksha, or the oeuvre of the Telugu director KSR Doss – but on the whole he stays close to the mainstream: you won’t find the obscure C-movies that many fans are now digging up and writing about online, or even something by the Ramsay Brothers.

Stadtman casts his net wide, writing about those cornerstones of the Bachchan era, Zanjeer, Deewaar and Amar Akbar Anthony, as well as a much less seen Amitabh film, the Deven Varma-directed Besharam; stylish, big-budget epics such as BR Chopra’s The Burning Train and Feroz Khan’s Qurbani, as well as films with more modest ambitions such as the Shashi Kapoor-starrers Chor Machaye Shor and Fakira. Some of the inclusions can readily be identified as cult B-movies – Gunmaster G9: Surakksha, or the oeuvre of the Telugu director KSR Doss – but on the whole he stays close to the mainstream: you won’t find the obscure C-movies that many fans are now digging up and writing about online, or even something by the Ramsay Brothers.

Plenty of tough love emerges in the process. Through watching dozens of films, he seems to have developed a genuine interest in such personalities as Zeenat Aman, Amjad Khan, even Jeevan and Dara Singh. I thoroughly approve of his Dharmendra-love, by the way: he shows an appreciation for the star’s combination of “physicality and fitful soulfulness” in films like Seeta aur Geeta and Yaadon ki Baaraat, and there is evidence that he may have been able to appreciate the quieter, more introspective side of Dharmendra as seen in films like Anupama or Satyakam (which could never have been included in this book). And take this observation about Shatrughan Sinha: “He doesn’t swing between comedy and drama as other contemporary stars might. During his most bellicose moments there is instead the subtlest hint of a wink, making him a joy to watch without sacrificing the intensity of the moment. And seeing that intensity, his famed rivalry with Bachchan becomes all the more understandable.”

been able to appreciate the quieter, more introspective side of Dharmendra as seen in films like Anupama or Satyakam (which could never have been included in this book). And take this observation about Shatrughan Sinha: “He doesn’t swing between comedy and drama as other contemporary stars might. During his most bellicose moments there is instead the subtlest hint of a wink, making him a joy to watch without sacrificing the intensity of the moment. And seeing that intensity, his famed rivalry with Bachchan becomes all the more understandable.”

Nor does he hold back about the things that don’t work for him. Here is a description of Randhir Kapoor’s character in Ram Bharose (or possibly a description of Kapoor himself): “He comes across as a freakishly, creepily desexualized man-child, basically Baby Huey without the diaper.” Dev Anand, pawing women young enough to be his daughters, affects Stadtman’s ability to fully enjoy films such as Warrant and Kalabaaz. And of Manoj Kumar’s exhausting righteousness, he says: “It’s difficult to criticize Roti Kapda aur Makaan for fear of seeming insensitive to its subject matter. But the truth is that one is aware enough of the gravity of that subject without Kumar’s onslaught of flag overlays and on-the-nose monologizing – to the extent that criticizing it almost seems like a form of self-defence.”

Passages like these (or the one where he describes the Asrani and Jagdeep comic interludes in Sholay as a superfluous waste of time) are gladdening, because they indicate that Stadtman isn’t patronising all these films as anything-goes exotica. Instead he is according them – the bulk of them, at least – the dignity of analysis, identifying areas where they work and where they don’t. He is applying standards of criticism to works that many people (including many Indians) sometimes dismiss as being criticism- and analysis-resistant.

I had a gripe about some of the inclusions. The musical Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, the pleasant thriller Victoria No 203, the family social Dil aur Deewaar and the cross-dressing comedy Rafoo Chakkar in a book about “Indian Action Cinema”? (Stadtman does clarify that “Rafoo Chakkar is not an example of a great Indian action film, but instead a great example of how, in the Bollywood of the 1970s, the elements of the Indian action film were irrepressible. Were audience expectations such by 1974 that not even a remake of a madcap American romantic comedy could be free of a sadistic villain in a Nehru jacket with a cat in his lap?” But the American film in question, Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot, was hardly shorn of breakneck action scenes and sinister villains itself, its plot-mover being a Prohibition Era gangland massacre.)

I had a gripe about some of the inclusions. The musical Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, the pleasant thriller Victoria No 203, the family social Dil aur Deewaar and the cross-dressing comedy Rafoo Chakkar in a book about “Indian Action Cinema”? (Stadtman does clarify that “Rafoo Chakkar is not an example of a great Indian action film, but instead a great example of how, in the Bollywood of the 1970s, the elements of the Indian action film were irrepressible. Were audience expectations such by 1974 that not even a remake of a madcap American romantic comedy could be free of a sadistic villain in a Nehru jacket with a cat in his lap?” But the American film in question, Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot, was hardly shorn of breakneck action scenes and sinister villains itself, its plot-mover being a Prohibition Era gangland massacre.)

There are a few typos and minor errors too. The Sholay entry tells us its success ensured “not only that Amjad Khan would always be bad, but that Hema Malini would always be garrulous”. Neither assertion is true: Khan, despite Gabbar’s long shadow, convincingly played sympathetic roles not just in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj ke Khiladi but also in mainstream films like Yaarana and Pyaara Dushman – he was certainly never typecast to the degree that less personable “specialist villains” like Ranjeet or Shakti Kapoor were. And Malini rarely played someone as chatty as Basanti again; instead she settled deeper into dignified, imperial-beauty parts as she headed towards matrimony.

Also, it may be a bit much to refer to Abhishek Bachchan as a “superstar”. Or to call Dharmendra’s son Sonny (sic) “an aspiring action hero” when he has been in films for 30 years. But these little things can be forgiven.

As an outsider, Stadtman had to make his peace with the episodic form of mainstream Hindi cinema, and it almost feels like some of those tonal shifts made their way into his own writing. In a piece about Manmohan Desai’s Parvarish, he goggles at the “action scene” in where a bathtub toy pretends to be an actual submarine (complete with a bobbing plastic doll pretending to be Tom Alter, if my memory serves me right) – but also makes a serious observation about how this film, by coming down on the nurture side of the nature-nurture debate, is a bit of an outlier in a Hindi-film universe where family ties have a mystical quality. Stadtman should know about that last bit – he is part of the Bollywood family now. This book is the locket fragment that helps him prove he is a lost-and-found sibling to us homegrown fans.

------------------

[Some old, related posts: on The Burning Train; ; Parvarish; Bob Christo; ensemble classics; and above all, Jeetendra. And on a more serious note, some thoughts on cultural distance in this long piece about Satyajit Ray]

When I heard an American had written a book about the “funky” Hindi cinema of the 70s, my first reaction was a proprietary sense of unease. Something like the emotion that (I am told) my Bengali friends experience when I, a mere north Indian, have the temerity to discuss Satyajit Ray’s or Ritwik Ghatak’s cinema even though some of the cultural and lingual nuances are beyond my grasp (and the DVD subtitling is often terrible anyway).

Which is to say that even before opening Todd Stadtman’s Funky Bollywood: The Wild World of 1970s Indian Action Cinema , I was readying to roll my eyes at a bit of analysis that “didn’t get it”, condescension directed towards movies I thought highly of – or, just as bad, an undiscerning celebration of mediocrity just because of its perceived kitsch value. If these movies have to be celebrated or trashed, it’s people like me who should do it, I muttered to myself – not someone who didn’t grow up with them and has never even lived in India. I pictured Stadtman as Bob Christo in the climactic fight scene of Disco Dancer, and myself as Mithun laying a bit of the old dhishoom-dhishoom on this firangi noggin while Helen, escorted by dancers in black-face, cavorted about us in a peacock-feather outfit, and we all dodged around a pool containing smoky pink acid and plastic sharks.

However, this defensive nervousness about Stadtman’s book faded once I began reading it. It’s true that he was drawn to 1970s Hindi cinema by its colourful over-the-topness, and that his publishers have had fun with glitzy photos and trivia boxes (e.g. the sequence of images showing a mini-skirted Jeetendra transforming into a snake in Nagin while Sunil Dutt, rifle in hand, stands by stoically) – but this is not in essence a frivolous book hurriedly thrown together

to capitalize on a market for corn and cheese. Stadtman has put thought into it. He writes with affection, and with the ambivalence that often makes this sort of writing so compelling – where one gets the sense that the author is struggling with his own responses to a film. Fans of pop culture that tends to get labeled “trash” (or “great trash”, to use Pauline Kael’s simplistic formulation for movies she loved but couldn’t think of as having artistic merit) will know the feeling.

to capitalize on a market for corn and cheese. Stadtman has put thought into it. He writes with affection, and with the ambivalence that often makes this sort of writing so compelling – where one gets the sense that the author is struggling with his own responses to a film. Fans of pop culture that tends to get labeled “trash” (or “great trash”, to use Pauline Kael’s simplistic formulation for movies she loved but couldn’t think of as having artistic merit) will know the feeling. Stadtman is hardly the first non-Indian writer to have developed a strong kinship with Hindi cinema. Other such fans – such as the bloggers Beth Watkins, Greta Kaemmer, Mike Enright and Carla Miriam Levy – all have their own stories about how they became interested in these films. In his introduction Stadtman explains that as a longtime cult-movie enthusiast, he came to 1970s Bollywood after having been through the Mexican lucha libre filmography as well as Turkish superhero mash-ups: he was seeking “speed, violence and garish style […] but cloaked in a cultural context that makes it all seem somehow fresh and new again”. Given this brief, and the glut of eye-popping material that mainstream Hindi films provided him, he might easily have constructed the whole book around tongue-in-cheek descriptions of costumes, props and villains’ lairs – such as this one from his account of the 1978 Azaad:

The Machine of Death includes dozens of swinging spiked balls arrayed around a lava pit like a deadly game of Skittle Bowl, a tunnel lined with spinning buzz-saw blades on sticks leading to a giant industrial fan with saw-toothed blades, and a cavernous hall that shakes, dislodging hundreds of empty glass bottles to shatter down on whoever passes through. This […] strikes me as potentially being extremely troublesome to set up again once sprung.But he also tries to understand the workings of the Indian film industry, the sort of viewer it was reaching out to, the nature of the star system, even the sociological underpinnings such as the discontentment in the country around Emergency time. He identifies the many foreign influences on these movies – from the spaghetti western to James Bond – but is aware of the Indian storytelling traditions that allowed a film to change its tone as rapidly as the hero and heroine change clothes in musical sequences, so that even a Dirty Harry or Godfather copy (Khoon Khoon and Dharmatma respectively) might have songs and slapstick comedy. And he understands that this cinema was designed to be a dream factory, “with dazzling fantasies of escape”, but also had to ensure that prescribed standards of morality were upheld (a paradox that helps explain why all those spectacular villains’ dens – and the vamps dancing in them – needed to be marveled at but destroyed in the end).

Stadtman casts his net wide, writing about those cornerstones of the Bachchan era, Zanjeer, Deewaar and Amar Akbar Anthony, as well as a much less seen Amitabh film, the Deven Varma-directed Besharam; stylish, big-budget epics such as BR Chopra’s The Burning Train and Feroz Khan’s Qurbani, as well as films with more modest ambitions such as the Shashi Kapoor-starrers Chor Machaye Shor and Fakira. Some of the inclusions can readily be identified as cult B-movies – Gunmaster G9: Surakksha, or the oeuvre of the Telugu director KSR Doss – but on the whole he stays close to the mainstream: you won’t find the obscure C-movies that many fans are now digging up and writing about online, or even something by the Ramsay Brothers.

Stadtman casts his net wide, writing about those cornerstones of the Bachchan era, Zanjeer, Deewaar and Amar Akbar Anthony, as well as a much less seen Amitabh film, the Deven Varma-directed Besharam; stylish, big-budget epics such as BR Chopra’s The Burning Train and Feroz Khan’s Qurbani, as well as films with more modest ambitions such as the Shashi Kapoor-starrers Chor Machaye Shor and Fakira. Some of the inclusions can readily be identified as cult B-movies – Gunmaster G9: Surakksha, or the oeuvre of the Telugu director KSR Doss – but on the whole he stays close to the mainstream: you won’t find the obscure C-movies that many fans are now digging up and writing about online, or even something by the Ramsay Brothers. Plenty of tough love emerges in the process. Through watching dozens of films, he seems to have developed a genuine interest in such personalities as Zeenat Aman, Amjad Khan, even Jeevan and Dara Singh. I thoroughly approve of his Dharmendra-love, by the way: he shows an appreciation for the star’s combination of “physicality and fitful soulfulness” in films like Seeta aur Geeta and Yaadon ki Baaraat, and there is evidence that he may have

been able to appreciate the quieter, more introspective side of Dharmendra as seen in films like Anupama or Satyakam (which could never have been included in this book). And take this observation about Shatrughan Sinha: “He doesn’t swing between comedy and drama as other contemporary stars might. During his most bellicose moments there is instead the subtlest hint of a wink, making him a joy to watch without sacrificing the intensity of the moment. And seeing that intensity, his famed rivalry with Bachchan becomes all the more understandable.”

been able to appreciate the quieter, more introspective side of Dharmendra as seen in films like Anupama or Satyakam (which could never have been included in this book). And take this observation about Shatrughan Sinha: “He doesn’t swing between comedy and drama as other contemporary stars might. During his most bellicose moments there is instead the subtlest hint of a wink, making him a joy to watch without sacrificing the intensity of the moment. And seeing that intensity, his famed rivalry with Bachchan becomes all the more understandable.” Nor does he hold back about the things that don’t work for him. Here is a description of Randhir Kapoor’s character in Ram Bharose (or possibly a description of Kapoor himself): “He comes across as a freakishly, creepily desexualized man-child, basically Baby Huey without the diaper.” Dev Anand, pawing women young enough to be his daughters, affects Stadtman’s ability to fully enjoy films such as Warrant and Kalabaaz. And of Manoj Kumar’s exhausting righteousness, he says: “It’s difficult to criticize Roti Kapda aur Makaan for fear of seeming insensitive to its subject matter. But the truth is that one is aware enough of the gravity of that subject without Kumar’s onslaught of flag overlays and on-the-nose monologizing – to the extent that criticizing it almost seems like a form of self-defence.”

Passages like these (or the one where he describes the Asrani and Jagdeep comic interludes in Sholay as a superfluous waste of time) are gladdening, because they indicate that Stadtman isn’t patronising all these films as anything-goes exotica. Instead he is according them – the bulk of them, at least – the dignity of analysis, identifying areas where they work and where they don’t. He is applying standards of criticism to works that many people (including many Indians) sometimes dismiss as being criticism- and analysis-resistant.

I had a gripe about some of the inclusions. The musical Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, the pleasant thriller Victoria No 203, the family social Dil aur Deewaar and the cross-dressing comedy Rafoo Chakkar in a book about “Indian Action Cinema”? (Stadtman does clarify that “Rafoo Chakkar is not an example of a great Indian action film, but instead a great example of how, in the Bollywood of the 1970s, the elements of the Indian action film were irrepressible. Were audience expectations such by 1974 that not even a remake of a madcap American romantic comedy could be free of a sadistic villain in a Nehru jacket with a cat in his lap?” But the American film in question, Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot, was hardly shorn of breakneck action scenes and sinister villains itself, its plot-mover being a Prohibition Era gangland massacre.)

I had a gripe about some of the inclusions. The musical Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, the pleasant thriller Victoria No 203, the family social Dil aur Deewaar and the cross-dressing comedy Rafoo Chakkar in a book about “Indian Action Cinema”? (Stadtman does clarify that “Rafoo Chakkar is not an example of a great Indian action film, but instead a great example of how, in the Bollywood of the 1970s, the elements of the Indian action film were irrepressible. Were audience expectations such by 1974 that not even a remake of a madcap American romantic comedy could be free of a sadistic villain in a Nehru jacket with a cat in his lap?” But the American film in question, Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot, was hardly shorn of breakneck action scenes and sinister villains itself, its plot-mover being a Prohibition Era gangland massacre.)There are a few typos and minor errors too. The Sholay entry tells us its success ensured “not only that Amjad Khan would always be bad, but that Hema Malini would always be garrulous”. Neither assertion is true: Khan, despite Gabbar’s long shadow, convincingly played sympathetic roles not just in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj ke Khiladi but also in mainstream films like Yaarana and Pyaara Dushman – he was certainly never typecast to the degree that less personable “specialist villains” like Ranjeet or Shakti Kapoor were. And Malini rarely played someone as chatty as Basanti again; instead she settled deeper into dignified, imperial-beauty parts as she headed towards matrimony.

Also, it may be a bit much to refer to Abhishek Bachchan as a “superstar”. Or to call Dharmendra’s son Sonny (sic) “an aspiring action hero” when he has been in films for 30 years. But these little things can be forgiven.

As an outsider, Stadtman had to make his peace with the episodic form of mainstream Hindi cinema, and it almost feels like some of those tonal shifts made their way into his own writing. In a piece about Manmohan Desai’s Parvarish, he goggles at the “action scene” in where a bathtub toy pretends to be an actual submarine (complete with a bobbing plastic doll pretending to be Tom Alter, if my memory serves me right) – but also makes a serious observation about how this film, by coming down on the nurture side of the nature-nurture debate, is a bit of an outlier in a Hindi-film universe where family ties have a mystical quality. Stadtman should know about that last bit – he is part of the Bollywood family now. This book is the locket fragment that helps him prove he is a lost-and-found sibling to us homegrown fans.

------------------

[Some old, related posts: on The Burning Train; ; Parvarish; Bob Christo; ensemble classics; and above all, Jeetendra. And on a more serious note, some thoughts on cultural distance in this long piece about Satyajit Ray]

Published on April 04, 2015 00:30

April 3, 2015

On Breaking the Bow, Sita's Sister and other myth-remakers

[Did this for my Forbes Life column. Possibly my 30th or 40th piece in the last few years about epic/mythology retellings, but one never runs out of things to say]

-------------------------------

Anyone who closely follows Indian publishing would have noted a few years ago that retellings of mythological tales were becoming a sub-genre of contemporary fiction. Well, things have progressed since then and it is now observed, particularly in more sceptical quarters, that such books are a cottage industry unto themselves. The last time I went to a bookstore (you know, the physical kind that some of us still trudge to like museum-goers), I saw an entire shelf packed with titles that read “The Mahabharata Quest” and “The Ramayana Code” and “Draupadi in High Heels” and such. And that was only the “new popular fiction” section – it didn’t include older titles such as the multi-volume, fantasy-style renderings by Ashok Banker, beginning with Prince of Ayodhya, or the English translations of acclaimed regional-language books such as SL Bhyrappa’s Parva, Pratibha Ray’s Yagnaseni or MT Vasudevan Nair’s Randaamoozham .

No doubt many of the new books are attempts to cash in on the popularity of pre-existing stories by making a few superficial changes and repackaging them – or even creating hybrids that hope to replicate the success of Western thrillers like The Da Vinci Code. Yet amidst the dross there are also a few genuine efforts to reexamine conventional perspectives and deal with less well-known subplots. Sharath Komarraju’s

The Winds of Hastinapur

, for instance, doesn’t try to capitalise on the Mahabharata’s most popular episodes; instead, the author directs his imagination and empathy at the epic’s early passages, which many casual readers aren’t familiar with – the childhood of Ganga and Shantanu’s son Prince Devavrata (later to be known as Bheeshma), the tangle of succession issues that results from his oath of celibacy, and his stepmother Satyavati’s desperate efforts to keep the throne of Hastinapura secure.

reexamine conventional perspectives and deal with less well-known subplots. Sharath Komarraju’s

The Winds of Hastinapur

, for instance, doesn’t try to capitalise on the Mahabharata’s most popular episodes; instead, the author directs his imagination and empathy at the epic’s early passages, which many casual readers aren’t familiar with – the childhood of Ganga and Shantanu’s son Prince Devavrata (later to be known as Bheeshma), the tangle of succession issues that results from his oath of celibacy, and his stepmother Satyavati’s desperate efforts to keep the throne of Hastinapura secure.

Another notable entry in the category is the anthology Breaking the Bow , which collects speculative fiction inspired by the Ramayana. Editors Vandana Singh and Anil Menon were clear about their brief for the collection: they didn’t want wholesale retellings but tales that elaborated on the known elements of the mythological universe. For this reason, they even politely rejected a story by Manjula Padmanabhan, set in the future with all the characters gender-reversed: Rama as Rashmi, Lakshman as Lakshmi, Sita as Sidhangshu. (Padmanabhan subsequently did another story for the collection, centred on Ravana’s wife Mandodari; both stories can be found in her own collection Three Virgins.) As often with anthologies, the result is a little uneven, but includes many fine pieces such as Aishwarya Subramanian’s “Making”. Here, the main Ramayana story is told in short vignettes and always from a slightly unsettling, off-kilter viewpoint, with creation and destruction (or making and unmaking) being running themes throughout. The characters are addressed by their more obscure names – Mythili for Sita, Meenakshi for Surpanakha – and Rama’s divinity, though accepted, is not celebrated as something warm or affirmative; this is a moody, megalomaniacal God. (“He must act out these petty human performances, as if he could not merely think different circumstances into existence. So he performs rage, and standing on the edge of a sea he could part with a mere flick of his hand sends mortal creatures to do his work instead.”)

If many retellings search for nuance by lending a sympathetic ear to the nominal “bad guys” – to overturn the “history as written by the victors” narrative – Anand Neelakantan’s patchy but often provocative Ajaya: Epic of the Kaurava Clan goes to the extreme of turning the envious Kaurava Duryodhana into a thoughtful, sympathetic hero (who has the support and friendship of many high-minded characters such as Balarama and Ashwatthama) and the Pandavas into the antagonists – not villains exactly, but buffoons who don’t deserve all the sympathy they get, and who are too easily made puppets by their cousin Krishna “who believes he has come to this world to save it from evil”. (Note what a difference that “believes” makes to the sentence! Such little touches are vital to these storytelling departures.)