In praise of Gulzar

[This is the last of my fortnightly columns for Business Standard Weekend. Have written that column for over 10 years and I will miss it, but it was time to move on. Will continue to do the occasional standalone piece for BSW though]

---------------------------------------

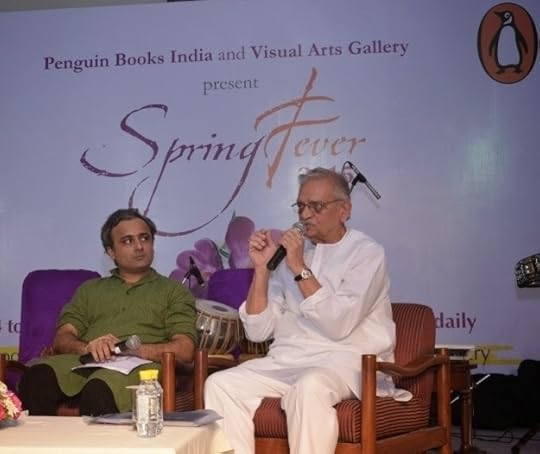

I am not easily star-struck, or daunted by the physical proximity of a great achiever, even when it’s someone I admire – yet there I was at the India Habitat Centre last week, moderating an event for the Penguin Spring Fever festival, when a part of me froze. Like a beam of light shooting through mist, this thought had leapt into my head: “The man sitting next to me has worked closely with Bimal Roy…and with Anurag Kashyap. He composed a gentle, meditative song for a classic like Bandini more than 50 years ago, but also won an Oscar for an exuberant number in a 2009 film.”

For an amateur film historian, it’s a staggering thought. The period mentioned above covers close to 75 percent of the history of sound cinema in this country, and Gulzar saab has not just been there through it, he has shaped a great deal of it with his own sensibility. As songwriter and occasionally dialogue-writer, he has made vital contributions to the work of Roy and Kashyap and dozens of directors in between, informing the mood of so many key films…and this in addition to helming many fine movies of his own.

For an amateur film historian, it’s a staggering thought. The period mentioned above covers close to 75 percent of the history of sound cinema in this country, and Gulzar saab has not just been there through it, he has shaped a great deal of it with his own sensibility. As songwriter and occasionally dialogue-writer, he has made vital contributions to the work of Roy and Kashyap and dozens of directors in between, informing the mood of so many key films…and this in addition to helming many fine movies of his own.

Most remarkably, he has reinvented himself along the way. If Gulzar had retired from films at the end of the 1980s – the decade that marked the twilight of the beloved “middle cinema” epitomised by him, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterji – his legacy would still have been a solid, secure one. Instead, as Hindi cinema began to shift towards the edgier, more globalised forms of expression that would mark the multiplex era, he found fresh inspiration through his collaborations with Vishal Bhardwaj (who went from composing for Gulzar’s film Maachis to becoming a celebrated director in his own right) and AR Rahman. Despite having himself been weaned on relatively straightforward narrative-driven cinema, he has relished the chance to work on formally unusual movies such as No Smoking, Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola and Jhoom Barabar Jhoom, inspiring a new generation of fans along the way.

The IHC amphitheatre last week seemed overrun by these young fans (the average age of the large audience couldn’t have been more than 30-35 years), but the man in the spotlight may have been the most young-at-heart person in attendance. It’s worth remembering that Gulzar has always had a naughty streak that belies the image of the venerable poet unvaryingly dressed in white kurta-pyjama. One of his notable qualities – a rare one for a man who, by his own admission, came to cinema from the world of serious literature – has been his ability to switch, seamlessly and often within the same stanza, between the soulful and the flippant. When he was a young man, his use of unusual metaphors often confounded purists: what is this aankhon ki mahekti khushboo, Rahi Masoom Raza once asked him, referring to a lyric from the film Khamoshi. “How can an eye have fragrance?”

As early as the mid-1960s, he was using apparently discordant English words to fine effect in Hindi songs: in a musical scene in the lovely 1965 comedy Biwi aur Makaan , Keshto Mukherjee and Biswajit – pretending to be women and slowly becoming sensitive to the travails of their adopted sex – lament while washing clothes, “Roz yeh naatak, roz yeh makeup […] Pehle pant-coat dhota tha, ab petticoat dhoti hoon.” Forty years later, as my friend Uday Bhatia writes in this excellent piece, young fans were still finding it counter-intuitive that a poet of Gulzar’s pedigree would use the line “personal se sawaal karte hain” in “Kajara Re”.

But then the legend himself is not conservative in the way that some of his fans are. Unlike them, he has little time for the rose-tinted notion that the past was always a better place than the present, that the films and music of today represent a degradation. Kashyap’s very abstract

No Smoking

, which he worked on in 2007, was the high watermark of his achievement as a poet-lyricist, he told me before his session – even though he originally had a hard time understanding the concept of the film. And he spoke approvingly of the high standards of professionalism in today’s film industry – it being a time of bound scripts (usually unheard of in the 1970s) and more attention to detail in areas such as production design and research.

But then the legend himself is not conservative in the way that some of his fans are. Unlike them, he has little time for the rose-tinted notion that the past was always a better place than the present, that the films and music of today represent a degradation. Kashyap’s very abstract

No Smoking

, which he worked on in 2007, was the high watermark of his achievement as a poet-lyricist, he told me before his session – even though he originally had a hard time understanding the concept of the film. And he spoke approvingly of the high standards of professionalism in today’s film industry – it being a time of bound scripts (usually unheard of in the 1970s) and more attention to detail in areas such as production design and research.

With the nature of the musical sequence in Hindi cinema having undergone changes, lyric-writing has become more challenging – and invigorating – for him. In a 70s film like Aandhi, Gulzar could use exalted language for the songs, having the characters sing “Tum aa gaye ho, noor aa gaya hai / Nahin toh chiraagon se lau jaa rahi thi” – lines that the same characters would certainly not have used in the “prose” segments of the film, where their dialogue would be more casual and everyday. It was understood at the time that a song marked a break in narrative space and logic.

In contemporary cinema though, there is more self-consciousness about the need to “realistically” integrate songs with narrative: they are either used as an accompaniment to the soundtrack, with the actors not lip-synching to the words, or when they are sung on screen, the idea is to be authentic. So when a gangster sings in Satya, the words – “Goli maar bheje mein” – should match his speech elsewhere in the film. The item song “Beedi Jalayele” (Omkara) is raunchy and suggestive, but that’s because the priority is to be truthful to the rustic setting. How would these people express themselves in this situation? What Gulzar saab has been doing in his recent work is to catch such truths and still make lasting poetry out of them. I hope he continues for many more years.

---------------------------------------

I am not easily star-struck, or daunted by the physical proximity of a great achiever, even when it’s someone I admire – yet there I was at the India Habitat Centre last week, moderating an event for the Penguin Spring Fever festival, when a part of me froze. Like a beam of light shooting through mist, this thought had leapt into my head: “The man sitting next to me has worked closely with Bimal Roy…and with Anurag Kashyap. He composed a gentle, meditative song for a classic like Bandini more than 50 years ago, but also won an Oscar for an exuberant number in a 2009 film.”

For an amateur film historian, it’s a staggering thought. The period mentioned above covers close to 75 percent of the history of sound cinema in this country, and Gulzar saab has not just been there through it, he has shaped a great deal of it with his own sensibility. As songwriter and occasionally dialogue-writer, he has made vital contributions to the work of Roy and Kashyap and dozens of directors in between, informing the mood of so many key films…and this in addition to helming many fine movies of his own.

For an amateur film historian, it’s a staggering thought. The period mentioned above covers close to 75 percent of the history of sound cinema in this country, and Gulzar saab has not just been there through it, he has shaped a great deal of it with his own sensibility. As songwriter and occasionally dialogue-writer, he has made vital contributions to the work of Roy and Kashyap and dozens of directors in between, informing the mood of so many key films…and this in addition to helming many fine movies of his own.Most remarkably, he has reinvented himself along the way. If Gulzar had retired from films at the end of the 1980s – the decade that marked the twilight of the beloved “middle cinema” epitomised by him, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterji – his legacy would still have been a solid, secure one. Instead, as Hindi cinema began to shift towards the edgier, more globalised forms of expression that would mark the multiplex era, he found fresh inspiration through his collaborations with Vishal Bhardwaj (who went from composing for Gulzar’s film Maachis to becoming a celebrated director in his own right) and AR Rahman. Despite having himself been weaned on relatively straightforward narrative-driven cinema, he has relished the chance to work on formally unusual movies such as No Smoking, Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola and Jhoom Barabar Jhoom, inspiring a new generation of fans along the way.

The IHC amphitheatre last week seemed overrun by these young fans (the average age of the large audience couldn’t have been more than 30-35 years), but the man in the spotlight may have been the most young-at-heart person in attendance. It’s worth remembering that Gulzar has always had a naughty streak that belies the image of the venerable poet unvaryingly dressed in white kurta-pyjama. One of his notable qualities – a rare one for a man who, by his own admission, came to cinema from the world of serious literature – has been his ability to switch, seamlessly and often within the same stanza, between the soulful and the flippant. When he was a young man, his use of unusual metaphors often confounded purists: what is this aankhon ki mahekti khushboo, Rahi Masoom Raza once asked him, referring to a lyric from the film Khamoshi. “How can an eye have fragrance?”

As early as the mid-1960s, he was using apparently discordant English words to fine effect in Hindi songs: in a musical scene in the lovely 1965 comedy Biwi aur Makaan , Keshto Mukherjee and Biswajit – pretending to be women and slowly becoming sensitive to the travails of their adopted sex – lament while washing clothes, “Roz yeh naatak, roz yeh makeup […] Pehle pant-coat dhota tha, ab petticoat dhoti hoon.” Forty years later, as my friend Uday Bhatia writes in this excellent piece, young fans were still finding it counter-intuitive that a poet of Gulzar’s pedigree would use the line “personal se sawaal karte hain” in “Kajara Re”.

But then the legend himself is not conservative in the way that some of his fans are. Unlike them, he has little time for the rose-tinted notion that the past was always a better place than the present, that the films and music of today represent a degradation. Kashyap’s very abstract

No Smoking

, which he worked on in 2007, was the high watermark of his achievement as a poet-lyricist, he told me before his session – even though he originally had a hard time understanding the concept of the film. And he spoke approvingly of the high standards of professionalism in today’s film industry – it being a time of bound scripts (usually unheard of in the 1970s) and more attention to detail in areas such as production design and research.

But then the legend himself is not conservative in the way that some of his fans are. Unlike them, he has little time for the rose-tinted notion that the past was always a better place than the present, that the films and music of today represent a degradation. Kashyap’s very abstract

No Smoking

, which he worked on in 2007, was the high watermark of his achievement as a poet-lyricist, he told me before his session – even though he originally had a hard time understanding the concept of the film. And he spoke approvingly of the high standards of professionalism in today’s film industry – it being a time of bound scripts (usually unheard of in the 1970s) and more attention to detail in areas such as production design and research.With the nature of the musical sequence in Hindi cinema having undergone changes, lyric-writing has become more challenging – and invigorating – for him. In a 70s film like Aandhi, Gulzar could use exalted language for the songs, having the characters sing “Tum aa gaye ho, noor aa gaya hai / Nahin toh chiraagon se lau jaa rahi thi” – lines that the same characters would certainly not have used in the “prose” segments of the film, where their dialogue would be more casual and everyday. It was understood at the time that a song marked a break in narrative space and logic.

In contemporary cinema though, there is more self-consciousness about the need to “realistically” integrate songs with narrative: they are either used as an accompaniment to the soundtrack, with the actors not lip-synching to the words, or when they are sung on screen, the idea is to be authentic. So when a gangster sings in Satya, the words – “Goli maar bheje mein” – should match his speech elsewhere in the film. The item song “Beedi Jalayele” (Omkara) is raunchy and suggestive, but that’s because the priority is to be truthful to the rustic setting. How would these people express themselves in this situation? What Gulzar saab has been doing in his recent work is to catch such truths and still make lasting poetry out of them. I hope he continues for many more years.

Published on March 25, 2015 09:08

No comments have been added yet.

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers

Jai Arjun Singh isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.