Martin Fone's Blog, page 65

December 13, 2023

The Notting Hill Mystery

A review of The Notting Hill Mystery by Charles Warren Adams – 231201

Widely regarded as one of the first pieces, if not the first, of detective fiction, The Notting Hill Mystery, originally serialised in the magazine Once A Week between 1862 and 1863 and published as a book later that year under the pseudonym of Charles Felix, predates Emile Gaboriau’s L’Affaire Lerouge (1866) and Wilkie Collins’ Moonstone (1868). It has been reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series and the edition includes the original illustrations by George du Maurier, grandfather of Daphne.

For those of us interested in the development of the genre of crime fiction, it is an important piece of work, but it is more than a curiosity, a fossil presaging the development of a fully formed and resplendent species, as once it gets going it is a rattling good read. For me there was more than a little sense of déjà vu. As a former insurance underwriter I was occasionally presented with a file of papers representing a carefully conducted piece of investigation into the circumstances of a claim. Often the investigator would hint and suggest but leave the final question of policy indemnification to the wisdom of the wielder of the underwriting pen.

The book takes the form of a file of papers compiled by Ralph Henderson which distils for the Board of a Life Insurance company the claims of Baron R*** for a pay out of £5,000 in respect of the life of his wife, one of five policies he had taken out with different companies. If that is not enough to alert even the most blasé of underwriters, Henderson reveals that the Baron is a beneficiary of another legacy, this time worth £25,000, which resulted from a sequence of deaths which fell in the right chronological order in a relatively short period of time. The inevitable conclusion is that the Baron was more than an impartial observer of the tragedy that befell his immediate family, but is there enough evidence to refuse indemnity and bring a charge of murder?

There is a very Gothic feel about the book with its brooding atmosphere of menace, a world populated by gypsies, child kidnappers, poisoners, and an almost supernatural bond between the two sisters caught up in the spiral of events which results in three murders. Perhaps the most eye-catching and sensationalist feature of the book is the role played by mesmerism, a fad akin to hypnotism which was popular in certain circles during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was a form of quackery, the last resort for those who gained little comfort from more conventional forms of medicine.

Baron R**** was one of the leading mesmerists in London and it was through practising his quackery that he met his wife and was able to wheedle his way into their family and set his eyes on the pot of cash that lay within his grasp. The descriptions of the sessions and the reactions to them are fascinating, Adams treating the plight of the victims sympathetically. The reader leaves with the inescapable conclusion that mesmerism is a sham and that its practitioners are just seeking to exploit the vulnerable.

I found that the book started slowly and the structure of the book, in which Henderson painstakingly picks out salient facts and draws conclusions from a variety of sources and perspectives, means that there is no linear progression. Hints, suggestions, and cold facts appear, are lost sight of and then their significance becomes even more apparent as Henderson’s narrative unfolds. We have all the pieces of the jigsaw, but need to do some work ourselves to see the whole picture. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

One curious fact I enjoyed is that trapeze artists develop broad feet, something I had never given any thought to before and probably never will again.

December 12, 2023

Topical Cracker Jokes (2023)

Did you hear about the Christmas cake on display in the British Museum? It was Stollen.

Why is Elon Musk’s Christmas dinner so awkward? He can’t stop talking about his X.

Why isn’t Barbie having turkey for Christmas dinner this year? Chic-Ken is enough.

Why aren’t any schools allowed to put on a nativity this year? They couldn’t find a stable building.

What impact will the 20mph speed limit in Wales have on the charts this year? Chris Rea will be driving home for Easter.

December 11, 2023

The Crow’s Inn Tragedy

A review of The Crow’s Inn Tragedy by Annie Haynes – 231130

The third and final of Annie Haynes Inspector Furnival series, The Crow’s Inn Tragedy was originally published in 1927 and has been reissued by Dean Street Press. It is an engaging and, at times, thrilling murder mystery which takes its name from the chambers in which the story begins, but what particularly intrigued me about it was some of the undertones and themes which threaten to derail the whole story.

The consequences of the First World War, the so-called war to end all wars, were all-pervasive, especially for those who survived the fighting. Many had psychological scars and many found that the land of heroes was not ready or equipped to assimilate the return of its conquering heroes. Many drifted into poverty and crime, one such being Tony Collyer, whose financial plight persuades his father, the Reverend James Collyer, to go up to London with a view to selling an emerald cross, a valuable family heirloom, seeking the assistance of his brother-in-law, Luke Bechombe, partner at the Crown’s Inn chambers.

Luke’s nephew, Aubrey Todmarsh, was a conscientious objector during the war and has subsequently established a facility which seeks to rehabilitate ex-offenders and wayward youths. He is idealistic, supports the concept of the League of Nations and world peace, his views often jarring with those of his contemporaries who prefer more direct forms of action to resolve the world’s problems. These sections give a fascinating insight into the issues that were exercising many minds at the time and the long-lasting consequences of conflict.

Internationalism of another sort emerges as the story evolves with the emergence of a group of international jewel thieves, known imaginatively as the Yellow Gang, led by the Yellow Dog. This twist almost comes out of nowhere and adds an unexpected dimension to what seemed to be building up into a cosy murder mystery with a social conscience. The hand of the Yellow Gang is detected when Luke’s body is found in his office, having conducted some private jewel-related business with his chief clerk, Amos Thompson, and a mysterious visitor who is able to gain access via a convenient back passage. Is this the opportunity that Furnival has been waiting for to nail the Yellow Dog and his gang?

I had feared that this book would lurch into the dreadful territory trodden by Agatha Christie’s The Big Four, also published in 1927, but to her credit Haynes manages to resist the penny dreadful sensationalism that the plot twist offers and wrestles the book back on to a more conventional track, with the odd join showing.

One curious feature is the role of Steadman, a barrister and criminologist, who seems to be cast as Furnival’s amateur foil, but, unlike most amateur sleuths, he does not seem to add very much to the investigation, other than exercising his penchant for amateur dramatics and donning costumes and disguises. Haynes is very much on the side of the conventional police and her hero, the initiable Furnival, ferrets out the truth, although not without a scare or two along the way.

Haynes is an engaging writer with an easy style that draws the reader in. This is far from the perfect novel but once she has regained control of the wild beast that threatened to run away, Haynes delivers an intriguing mystery and a compelling solution.

December 10, 2023

Keen As Mustard

Inevitably, the success of Mrs Clements’ Durham mustard encouraged others to enter the mustard market. London had its first mustard factory, perhaps inappropriately at Garlick Hill, when Messrs Keen & Sons opened for business in 1742, supplying their product to taverns and chophouses. Despite their close association with mustard, they were not the origin of “keen as mustard”. This phrase first appeared in print in 1672 in William Walker’s Paroemiologie Anglo-Latina. By 1810 the London Journal was opining that “mustard seed is now used and esteemed by most of the quality and gentry”. Mustard had truly arrived.

Norwich was a latecomer to the English mustard saga, rising to prominence after Jeremiah Colman had bought a flour and mustard mill in Stoke Holy Cross on the River Tas, about four miles south of the city, in 1814. Blending brown mustard (Brassica juncea) with white (Sinapsis alba), both grown locally and sold at Wisbech market, his tangy condiment soon found favour. With a branch established in London’s Cannon Street in 1836, by 1851, the year of his death, he had about 100 employees.

Colman’s son, James, died three years later, leaving Jeremiah’s twenty-one year old grandson, Jeremiah James (JJ), to run the company. JJ immediately made his mark on the company, introducing its distinctive bright yellow packaging and bull’s head logo, not any old head but that of the Durham ox. It was more than a passing nod in the direction of Mrs Clements. By that time her company, now named Ainsley’s after her son-in-law, had been acquired by Colman’s.

After moving to larger premises inside Norwich on Carrow Road in 1865, Colman’s was appointed as mustard provider to Queen Victoria the following year and, in 1878, awarded medals for their starch and mustard products at the Paris Universal Exhibition, medals which are still illustrated on their tins. In another ground-breaking move in 1893, they became one of the first food processors to check the quality of their product, employing two chemists to inspect incoming mustard seeds.

After taking over Keen’s in 1903, they became the country’s principal English mustard manufacturer leaving the contributions of Tewkesbury and Durham a distant memory.

December 9, 2023

Espresso Perfetto

For those who like a supercharged burst of caffeine there is nothing better than an espresso. However, a group of American scientists claim to have cracked the secret of making a perfect espresso. The key ingredient is something that should be added before the beans are ground.

The scientists have found that when coffee is ground, the friction between the beans creates electricity, causing particles to lump together in the grinder. By adding water to the process reduces the amount of electricity produced, resulting in less coffee waste, stronger flavours and a tastier and more drink.

Their next goal is to crack the perfect cup of coffee.

More power to their elbow!

December 8, 2023

Banana Before Bed

Want a good night’s sleep? Try fruit just before you go to bed, say The Sleep Charity. Bananas, in particular, contain high levels of magnesium and potassium which help muscle relaxation and the amino acid, tryptophan, which stimulates production of brain-calming hormones.

Fruit, especially grapes, tart cherries, and strawberries, also encourages the production of melatonin, a hormone which plays a big role in determining the quality of your sleep.

I will give it a try.

December 7, 2023

The Grim Maiden

A review of The Grim Maiden by Brian Flynn – 231104

Always expect the unexpected with Brian Flynn, a writer who is not content to follow a tried and tested formula but who is willing to experiment with form and structure. Generally the experiment pays off and certainly the reader is never quite sure what they are in for when they read the first page of the first chapter. To my mind that is part of his attraction.

The Grim Maiden, the thirtieth in Flynn’s long running Anthony Bathurst series, was originally published in 1943 and has been reissued by Dean Street Press. It is more of a thriller than a traditional whodunit as there is no attempt to hide the identities of the culprits. The challenge for Bathurst, ably assisted by his long-standing ally at the Yard, Andrew MacMorran, is to work out what is going on, prevent further crimes being committed, and obtain enough evidence to ensure that justice is done.

Bathurst has two visits which set the tale up. One is from Richard Arbuthnot who is convinced that simply because a fellow commuter has had the same unopened library book, the Seamark Omnibus, on his lap for months that a crime is going to be committed and the other from a woman who is concerned that her brother, Regan, is missing. Bathurst’s suspicions are alerted when he discovers that the library did not have a copy of the book and Regan’s body is found on the road, supposedly the victim of a hit and run accident although there is evidence to suggest that this conclusion was arrived at too hastily.

Regan had given his sister seven sketches of women that he had drawn which Bathurst deduces provides a clue in the form of a cipher and pokes around in the garden of the house in which he lived, finding, amongst other things, a diary, which contains a number of initially disparate and confusing clues. That he is on to something is confirmed when Regan’s sister suffers the same fate as her brother.

It becomes a tale of organised crime, currency counterfeiting, and money laundering and one in which Bathurst gets actively involved, inveigling himself into the gang, albeit he is sent on an amusing wild goose chase as the Mr Bigs are not as naïve as he supposed them to be. The story takes on an altogether more grimmer and macabre aspect as the gang turn to extortion and child kidnap. Bathurst and MacMorran are too late to prevent the first abduction ending in tragedy but are able to prevent a second, amassing enough evidence along the way to be absolutely certain who the mastermind is. After all, child kidnapping is not a very British crime.

Helen Repton, from the female side of the Yard – who knew? – makes a cameo appearance and it is through her diligence that valuable clues that lead to the case’s resolution are obtained. Her reward, a few patronising and sexist pats on the back. As the case reaches its denouement, Bathurst once more throws himself into the lion’s den. He obtains some incriminating documentation, although why the gang allow him to keep them when he falls into their hands is a mystery.

It is almost at the end of the book that our hero meets the eponymous Grim Maiden, aka an Iron Maiden, an instrument of torture that crushes and spikes its victim to death. This is the fate that the Regans had suffered for knowing too much and from which Bathurst escapes in the nick of time by the deus ex machina-like appearance of Andrew MacMorran.

As the duo review the case, some loose ends are wrapped up. The book, which started the whole caper off, was hollowed out and was the means by which the counterfeit money was conveyed while the Maiden explains the references to Nuremburg. Flynn manages to knit the disparate strands of the story into a whole, but it rather strains credulity and relies a little too heavily on coincidence to be considered a triumph. It also has too many characters who flit in and out of the story to be anything other than the Bathurst show. As entertainment goes, it was fine but we know Flynn was capable of better.

December 6, 2023

Gin Aux Agrumes

The clue is in its name. La Distillerie de Monaco, Monaco’s only distillery, was originally founded by Philip Culazzo to produce L’Orangerie liqueur, but the principality is famous for three things, motor racing, gin palaces, and its citrus production, the latter once the mainstay of its local economy. Recognising the opportunity the local, high quality citrus offered to make a mark on the ginaissance, Philip added Gin Aux Agrumes to his distillery’s portfolio. They also produce a vodka.

If you love citrus, especially lemon, then this, the fifth of my selection from a recent trip to Constantine Store, home of Drinkfinder UK, will be right down your boulevard. It is a love letter to citric notes with bergamot, bitter and sweet orange, citron, grapefruit, lemon, and lime all having a role to play. To ensure that the result is not a zesty, sickly concoction, balance is provided by an undertone of juniper, ably assisted by ginger, lemon thyme (yes, more lemon), and Szechuan pepper. There may be more hiding in the undergrowth, but these are the main players.

On the nose there is the reassuring aroma of juniper, but the citrus notes also jostle for recognition. Sweet orange is very prominent, but the zestier, more bitter citric elements do a good job in keeping it in its place. There is very much a “come and get me” feeling to its smell, and it would be rude to refuse. In the glass, the spirit is clear with an ABV of 40%, and is much more bitter than I imagined it would be, juniper, ginger, wonderfully peppery Szechuan pepper, and the more bitter citric elements putting the sweeter notes in their place.

The addition of a premium tonic makes for an astonishing transformation. Whereas neat each element seems to be jostling for position, the tonic works in unison with the juniper to settle everything down and where there was muddle and confusion, all becomes harmonious. It becomes a marvellously smooth, refreshing gin, ideal for an early evening reviver (sun optional) and knocks other citrus-heavy gins that I have tasted into a cocked hat. It has clearly been designed as a gin for a G&T and it does its job remarkably well and reinforces how underrated the power of juniper is underrated in some circles.

Of course, you can only appreciate the merits of a gin once you have opened the bottle and to enhance the chances that it will be a bottle of Gin aux Agrumes that you will select from the groaning shelves, Philip has put in an extraordinary amount of care into its look. It is made of clear glass, tapering upwards from a square base, a short but steep shoulder, and a short neck which leads to a wooden stopper. The labelling at the front is minimal, consisting of just the name of the distillery just below the shoulder and the name of the spirit, the size of the contents and its ABV at the base.

There is a reason for that as it maximises the space for the image on the rear of the back labelling to be seen. And what a lovely image it is too, a beautiful painting of the Monegasque coastline visible through a citrus tree. The colours are vibrant and the style of the painting is reminiscent of the 1930s railway posters. It is clever and reinforces the impression that this is a serious and classy gin.

Until the next time, cheers!

December 5, 2023

Word Of 2023

It comes as no surprise given all the chatter about it, that Collins, the publishers of the dictionary, have awarded the title of Word of the Year to AI, the abbreviation for artificial intelligence, which they define as “the modelling of human mental functions by computer programs”. Perhaps I am being unduly pedantic but can an abbreviation really be a word? Have the lexicographers been hacked by a rogue piece of AI?

The shortlist included a couple of horrors where the prefix de- is used to denote a negative – de-influencing, an influencer who warns their followers to avoid certain products, lifestyle choices etc, and de-banking, having your bank account closed for reasons other than financial status. Nepotism or cases of Bob’s your uncle have given rise to nepo baby someone who owes their start in life or success to the influence of their famous parents, while a canon event is something that is “essential to the formation of an individual’s character or identity”.

Another prefix that has become trendy is ultra-, appearing in two words that made the shortlist, ultra-processed as in foods made up of “ingredients with little or no nutritional value” which have been “prepared using complex industrial methods”, and ultra-low emissions zone, which now embraces all of London in an attempt to drive out polluting vehicles.

A wonder drug, semaglutide, supposed to suppress appetite and cause weight loss, appears on a list which could have done a shot of it itself, and for the sports fan Bazball, a deluded attempt to change the style of test cricket, makes what is likely to be a short-lived but lively appearance at the crease.

For better or worse, AI is likely to outlive all the neologisms that 2023 has spawned.

December 4, 2023

London’s Eiffel Tower (2)

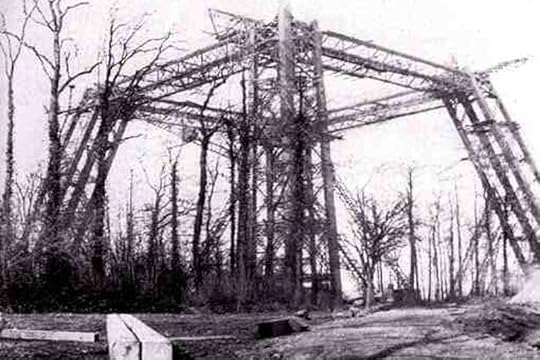

Fired with enthusiasm for the project to build a tower that would out do the Eiffel Tower, Sir Edward Watkin formed the International Tower Construction Company but investors did not match his zeal, a public subscription raised just £87,000, two-thirds of which came from his own railway company. Inevitably, this meant that the design had to be scaled back. One of consequences was that instead of being supported by eight legs, the revised design used just four, a decision that was to have ominous consequences for the structure’s viability.

Nevertheless, the foundations were laid in 1892 and construction work began in June 1893. At the same time a park was created, boasting boating lakes, waterfalls, ornamental gardens, cricket and football pitches, and various attractions and restaurants. A new station at Wembley Park was opened on the Metropolitan line, offering a journey of just twelve minutes from Baker Street, allowing visitors to reach it with ease and boosting the railway’s revenues. Opened in May 1894 the park quickly proved a success, attracting some 100,000 visitors that year.

The tower, however, was anything but. Watkin’s company soon ran into financial problems, resulting in further compromises on the design, and, because of the marshy conditions of the site, construction work fell dramatically behind schedule. Visitors to the park had to put up with the noise of construction making it anything but a haven of peace and tranquillity and numbers dropped with only 120,000 sampling its attractions in 1895. This in turn put further pressure on the project into which Sir Edward had ploughed £100,000 of his own money.

By September 1895, against all the odds, the first stage of the tower was completed, consisting of four enormous legs supporting a platform 155 feet in the air, which was accessible by lifts. Opened to the public in 1896, it was poorly patronised with only 18,500 of the 100,000 visitors to the park that year paying to go to the top. Part of the problem was that on the outer fringes of London the tower did not offer much of a view, certainly nothing to compare with the panoramic vistas seen from the Eiffel Tower.

Watkin’s recherché and far from altruistic choice of location had done nothing to ensure the ultimate success of his project. Indeed, what was envisaged as London’s tallest structure, ten times taller than the then tallest building, St Paul’s Cathedral and dwarfing even the Shard, quickly became an object of ridicule, dubbed variously as “Shareholders’ Dismay”, the “London Stump” and “Watkin’s Folly”.

Worse was to follow. The marshy soil on which the tower’s foundations were built coupled with the compromises in its design meant that the structure began to subside and lean dangerously. Watkin suffered a stroke and resigned his position as chairman of the Metropolitan Railway. Without his drive and vision, the project ran out of steam, the tower, still just a platform astride four legs, began to rust and deteriorate, and by 1899 the International Tower Construction Company had filed for voluntary liquidation.

In 1902, a year after Watkin’s death, the tower was declared unsafe and closed to the public and then was dismantled, the demolition team blasting the foundations to smithereens, an ignominious end to London’s rival to the Eiffel Tower. Watkin’s ambition was no stranger to failure, his vision of linking his railway with the French via a Channel tunnel collapsed when his Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company ran out of money in 1881 after drilling tunnels from Shakespeare Cliff and Sangatte 1.2 miles and one mile long respectively.

Nevertheless, the park still attracted visitors and had put the obscure hamlet of Wembley on the map. The Tower Construction Company, now reconfigured as the Wembley Park Construction Company in 1906, concentrated on building housing in the area and the British Empire Exhibition Stadium, opened in 1923 and better known as Wembley Stadium, was built on the spot Watkin had chosen for his tower.

In 2002, when the stadium was being redeveloped, workmen found four large concrete foundations underneath the pitch, the first and last vestiges of the tower. Once a nearby public house, The Watkin’s Folly, had closed in 2018, only Watkin Road, to the east of the stadium complex, remained as a reminder of London’s Eiffel Tower that never was.