Martin Fone's Blog, page 62

January 22, 2024

Brought To Light

A review of Brought To Light by E R Punshon – 231214

I only wish I can write a book as good as this when I am eighty-two. Originally published in 1954, two years before his death, and reissued by Dean Street Press, Brought To Light is the thirty-second novel in Punshon’s Bobby Owen which began in 1933 with Bobby a bobby on the beat. Now he is a Deputy Commander at the Yard with a licence to roam and act independently, two characteristics which play to the detective’s strengths.

The opening chapter sees Punshon at his best, setting up the story with economy and clarity. In the churchyard at Hillings-under-Manor lies the grave of Janet Merton, the mistress of a lauded poet, Stephen Asprey, who in his grief is said to have placed a casket containing his love letters and his last poems. The sexton, Hagen, unusually learned for a man in his position and unwilling to seek promotion, is paranoid that the grave will be opened and the casket removed. Edward Pyle, the proprietor of the Morning Daily, is campaigning for the grave to be opened as he intends to write a biography on Asprey. This horrifies the Duke of Blegborough as he fears that the contents of the letters will cast an unfavourable light on his dead wife.

Chrines, who claims to be the son from the relationship between Asprey and Hanet Merton, is also after the papers as he too is planning to write a biography. Asprey’s wife is also in the vicinity, anxious to preserve her husband’s reputation. To add some extra spice, the previous vicar of the parish, Dr Thorne, disappeared one evening and was presumed to be lost on the moors. His body was never found. Into this unusual maelstrom of heated passions with a Gothic twist of potential grave robbery boldly steps Bobby Owen.

Punshon takes time in developing the character of the odious Pyle who is used to getting his own way and has the knack of getting other people’s backs up. It is no surprise then when he is shot, and the caravan in which he was staying on the moor waiting for his opportunity, whether officially sanctioned or not, to open the grave is burned to the ground. Bobby’s task is to work out which of the suspects is guilty. Along the way he has to work out what really happened to Asprey’s letters and poems and to solve the mystery of Dr Thorne’s disappearance. A significant clue is a poem contained in Chrines’ recently published collection of poetry.

It is a tale of obsession and guilty secrets, populated with some fascinating characters. There is more than a little graphic horror with Punshon sparing no details in his description of the goriness of the deaths. The scene when Janet Merton’s grave is opened is vivid and has left an image that will stay with me for a long time. The brooding malevolent presence of the moor adds to the atmospheric feel of the book. I did miss the presence of Bobby’s wife, Olive, which meant that instead of deploying her as his sounding board and source of inspiration, we have to listen to his internal rationalising of what he has discovered so far, which works less well, I feel.

Nevertheless, there is much to admire in what is one of the best of Punshon’s later output and that he was able to pull it off at his advanced age is testament to the power of his creativity and his mastery of his craft. Remarkably, he was to publish three more Bobby Owen books before his death two years later.

January 20, 2024

Silent Pool Rare Citrus Gin

Although I am more a fan of traditional London Dry, juniper forward gins than of contemporary style gins, the team at Silent Pool Distillers from Albury near Guildford do make a tasty spirit. I had tried and reviewed their signature gin many moons ago and I was intrigued to see what their Rare Citrus Gin, which Santa had very kindly given me, was like.

One of the striking things about Silent Pool is the beauty of their bottle design and this is no exception. Instead of the blue of their Silent Pool Gin, the bottle is orange with the same design of botanicals on its circular main body. The shoulder is rounded, leading to a medium sized neck and a glass stopper, which is remarkably robust as I dropped it. Labelling is minimal, just “Silent Pool” on an orange band on the neck and some basic information, including that it is “distilled from grain” in white at the bottom of the bottle. What it lacks in information, this 50cl bottle containing a spirit with an ABV of 43% more than makes up for in style.

The pressure to find space in the crowded marketplace spawned by the ginaissance, has encouraged enthusiastic distillers to search for wonderful and exotic flavours with which to tickle our palates and find an edge. Unsurprisingly, the inspiration behind the Rare Citrus Gin came from a love of all things citrus but, more particularly, to introduce some new taste sensations that perhaps their topers have not experienced before. The Silent Pool’s citrus suppliers, based in Portugal, have around 360 varieties of citrus and the team sampled dozens to find the perfect combination that would provide a complex gin.

They settled on four. The first was Buddha’s hand or, to give it its botanical name, Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis, a curiously shaped citron whose zesty fruit is segmented into finger-like sections, rather like those seen on statues of Buddha, hence its name. The second is Natsu dai dai, which is thought to be a hybrid between sour orange or pummelo and mandarin. Growing to the size of a grapefruit when ripe with a yellowish orange rind, its flavour is refreshingly bitter and sweet, rather reminiscent of Seville orange marmalade. The third is Hirado Buntan, a cultivar which originated on Hirado Island in Japan in 1910. It is a large fruit, bright yellow when ripe with a flavour that is a pleasant mix of sugar and acid with hints of bitterness. The quartet is made up by Green Seville Oranges.

With all that gorgeous citrus, I feared that it would overwhelm the spirit but, surprisingly and all credit to the distiller’s craft, it is still a remarkably juniper-forward tipple, its earthiness and piney notes counterbalancing and bringing under control the sweet and bitter tones from the citrus that, initially, threatens to take charge. It is a complex and wonderful gin that showcases some of the more exotic citrons but in a way that will satisfy even the most critical traditionalist.

I could not resist a second glass.

Until the next time, cheers!

January 19, 2024

Dead Water

A review of Dead Water by Ngaio Marsh – 231213

Set in the Cornish coastal village of Portcarrow, the twenty-third book in Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn series, originally published in 1963, is one of her better ones using humour and drama to good effect. It starts with a young boy, Wally Trehern, an epileptic, who is plagued with warts which magically disappear when following an appearance of the Green Lady he washes his hands in the spring water of the local falls.

While most of the locals are sceptical about the healing properties of the spring, Elspeth Cost takes up its cause claiming that it cured her of asthma. Two years later, having out their initial scepticism to one side, Portcarrow has become a thriving tourist spot, visitors finding accommodation at the extended public house run by Major Barrimore and buying souvenirs from Elspeth’s shop.

However, trouble is just round the corner when Emily Pride inherits the land on which the spring is situated. She is appalled at the commercial exploitation of the spring, luring sick people to take its supposed healing waters rather than seeking conventional medical treatment, her ire stoked by the death of a friend in similar circumstances. The announcement of her intention to close the spring to the public unleashes howls of protest and Emily soon finds herself the recipient of threatening letters. As Alleyn’s former French tutor she asks him to help.

When Emily visits Portcarrow, the animosity towards her and her plans intensifies. She receives anonymous phone calls, is subjected to stone throwing, has an effigy with the sign Death delivered to her room, and narrowly avoids a trip wire causing Alleyn to take a more hands on role in protecting her. Inevitably, a body of a woman is found in the spring, having been struck on the head with a stone and drowned, but the twist is that it is not Emily Pride.

As Alleyn investigates, he discovers that there is more going on under the surface of Portcarrow than meets the eye and that there are deeper reasons behind the murder. The denouement is thrilling as Alleyn wrestles with the culprit on a launch in the middle of a storm, making a satisfying ending to an entertaining story. It helps that Alleyn is more integral to the story than in many I have read.

Marsh takes great delight in imbuing the names she uses with symbolism. Dead water is the name the locals give to the period at low tide when the island on which the spring is situated is linked to the mainland, but it also refers to a corpse in the water. Emily Pride, one of the two strong female characters in the story, is full of pride, stubborn, utterly determined, sure of her own mind and knows what is best for everyone else. Elspeth Cost, on the other hand, is obsessed with maximising the commercial opportunities that the Green Lady and the healing spring provides. That they clash is an inevitability.

The book is lighter and more humorous than many of Marsh’s stories. The highlight for me was the Festival of the Green Lady, a marvellous farce, which ends with all the attendees fleeing a rainstorm. Wonderful stuff.

At times my enthusiasm for Marsh’s Alleyn series has flagged but this has made me keen to carry on. If you are looking to dip into the world of Roderick Alleyn this might be a good place to start.

January 17, 2024

The Case Of The Abominable Snowman

A review of The Case Of The Abominable Snowman by Nicholas Blake – 231212

I do like a bit of ring composition and who better to deliver it than a poet? This, the seventh in Blake’s Nigel Strangeways series, originally published in 1941, begins with a snowman built to resemble Queen Victoria slowly melting to reveal a corpse inside. As the book draws to a conclusion, the scene is repeated and the identity of the body is revealed. The further twist is that it is not who we are led to believe it to be. Either side of these scenes we are treated to the circumstances which lead up to this astonishing discovery.

Blake aka Cecil Day-Lewis has fashioned an entertaining and intriguing story from unpromising beginnings, a country house owned by Hereward Restorick set in a part of the country which is blanketed in snow and contains the usual collection of motley characters including a rather creepy and sinister medic, Bogan.

The death which sparks the action provides a haunting image, a naked young woman with her face made up hanging from a beam. It is Elizabeth Restorick and it looks as though she had committed suicide. On closer inspection, Strangeways believes that this is a case of murder dressed up as suicide. Why otherwise would a woman have gone to bed, taken off her make up in front of the maid only to put it back on again, if she wasn’t expecting to entertain a guest, a lover perhaps?

We never meet Elizabeth aka Betty alive. What we learn about her comes from others and from Strangeways’ investigations. We learn of her troubled adolescence and an event in America which was to have a transformative effect on her life. However, for all that Elizabeth remains a rather aloof character, one around whom a plot has been constructed rather than a vibrant character who has met an untimely end.

There have also been other rum goings-on at the house, not least the bizarre behaviour of the cat, Scribbles, which Strangeways is initially invited to investigate, a ghostly appearance of Betty in the children’s room shortly before her death, and an attempt to poison Andrew Restorick. There is more than enough for Strangeways to get his teeth into.

The title of the book is clever and is key to the motivation behind the story. Yes, the snowman in the garden is abominable because it hides a body, but there is another connotation to snowman. It is a tale of drugs and the consequences of addiction. Initially hooked on marijuana – there is an aside where the difference between marijuana and hashish and the latter’s role in the derivation of assassin – Elizabeth progresses on to cocaine, “snow”, her supplier being an abominable snowman in the guise of Dr Bogan who is supposedly treating her for nervous disorders. As is often the case, the more prosaic American title for the book, The Corpse in the Snowman, misses this nuance.

There are really only two suspects and Strangeways lays a trap to smoke the culprit out but to the local police’s chagrin it goes wrong and both Dr Bogan and Andrew Restorick disappear, the presumption being that one has killed the other, but who has killed whom and where is the body. After an exhaustive and fruitless search of the area, after a car had been found in a snowdrift, a change in temperature leads to a thaw and they discover that the object of their search was in front of them all the time.

Nigel Strangeways is far from the infallible sleuth, a little too clever for his own good at times. Despite falling into a trap over the cause of Elizabeth’s death and misjudging the behaviour of the suspects, he gets there in the end. I enjoyed the book but there was something a little cold and clinical about the way the plot unfolded, apt though for a tale about snowmen.

January 16, 2024

The Case Of Elymas The Sorcerer

A review of The Case of Elymas the Sorcerer by Brian Flynn – 231211

Rather like Gladys Mitchell, but in a good way, you are never quite sure what you are going to get with a Brian Flynn, a writer who was never satisfied with slipping into a tried and tested template. With its exotic title, the thirty-first in his Anthony Bathurst series, originally published in 1945 and reissued by Dean Street Press, The Case of Elymas the Sorcerer conjures up an image of a tale with magical and possibly Gothic overtones. In truth, though, it is a rather conventional tale of murder and organised crime, the theft of historic works of art to order.

There is one moment where weirdness obtrudes, when Bathurst visits a house in London where he is greeted by a grotesque dwarf and is presented with a tableau of a tarantula, and a coffin over which a woman in a white robe is grieving and quoting Shakespeare. While it certainly provides a vivid image, it feels somewhat out of place with the rest of the book and does not really fit in with the rest of the book.

The same can be said about the scenes featuring the village simpleton, Frank Lord, whose coincidental appearance at the field is ultimately shrugged off as a red herring. These incidents enhance the impression that this is a book of episodes where the author is experimenting and has not quite settled on its tenor and format.

Elymas the Sorcerer does play an integral part in the resolution of the story. It is the subject of one of the tapestries by Raffaele that has been stolen to order and its unexpected presence out of place provokes a reaction that gives the culprit, who has been fencing these artefacts, away.

The road to getting there is long and convoluted. Bathurst, convalescing from a spell of muscular rheumatism, is taking the sea air at St Mead, surely a nod of the head to Miss Marple from the king of pastiche, as a guest of Neville Kemble, the brother of the Commissioner of Scotland Yard, Sir Austin. The break turns into a busman’s holiday as a body is discovered in nearby Ebsford’s field. It is naked and there are signs that the corpse was shaved after death, presumably to hide its identity.

Bathurst is called in to help the local police and makes some headway by unearthing a potential informant who suffers the same fate, found naked and dead in Ebsford’s field before he can spill the beans. MacMorran is sent from the Yard to assist and gradually Bathurst begins to piece together what has been going on. His method relies more on educated guesses than solid deduction and the reader has not enough clues to have a chance of beating the amateur sleuth to the solution.

One of the book’s highlights is its treatment of the local worthies that make up the leading lights of the council at Kersbrook-on-Sea, the local town. They are bumptious, full of their own importance, stitch up business for their own advantage and Flynn clearly has fun in mocking them.

I have seen the book described as a curate’s egg. That is clearly wrong as the poor curate’s egg was more bad than good. The quality of Elymas the Sorcerer is varied, but Flynn has managed, as usual, to fashion an enjoyable and entertaining tale that intrigues as it moves towards its dramatic denouement. It is worth a read.

January 15, 2024

Blue Monday

January can be a depressing month. Christmas has come and gone, leaving only its financial and emotional consequences to manage, New Year’s resolutions have fallen by the wayside, motivational levels are low, and we are desperate for something to look forward to. Show marketeers a psychological weakness and they are quick to seize on an opportunity. Psychologist Cliff Arnall coined the phrase “Blue Monday” in 2004 to describe the third Monday of January, today, when we are supposed to be at our lowest ebb for a travel firm to use in their advertising campaign to promote their holiday deals.

The phrase has stuck, even though on Arnall’s own admission the concept was little more than pseudoscience. However, recent research from Aviva suggests that the desire for something to look forward to begins even earlier, with 14% of Britons planning to search for and 12% intending to book a holiday during the festive season, in readiness for “Sun Saturday”, the first Saturday after New Year, when travel agents see the most activity and offers are supposed to be at their keenest. Not for nothing are commercial television and the press inundated with advertisements for dream holidays even before the first turkey’s wishbone has been snapped.

January 13, 2024

Aval Dor Cornish Dry Gin

I had come across Colwith Farm Distillery from Lanlivery in Cornwall before when I bought a bottle of their collaborative effort, Smuggled From Cornwall, and I will not repeat their backstory, interesting as it is, just follow the link. However, in late 2020 their own product line of gins and vodkas have undergone a rebrand and, confusingly, are marketed under a new name. Styled as Cornwall’s first plough to bottle distillery, its gins and vodkas use the potatoes sown and grown on the farm as their base, it is no surprise to learn that the name that they have chosen for their brand is Cornish for “potato”. For emmets like me it sounds stylish with a touch of Cornish mysticism. If you have your own language, use it I say!

Their Dry was originally sold as Stafford’s Dry Gin. The revamp of the bottle is seriously impressive and eye-catching. Made with frosted glass, it is circular in shape with rounded shoulders and a medium sized neck which leads to a black cap and a cork stopper. There is a very artistic and flourishing monogram on the upper part of the bottle and then the name of the spirit in black capitals. A black band about a third of the way up the bottle gives the distillery’s name in white using a mix of copperplate and capitals and an emerald green colour is used to denote “Dry Gin”. Towards the bottom there is the Cornish crest and either side the size of the bottle, 70cl, and the strength, 42% ABV. The whole effect is striking in its minimalism.

At the rear of the bottle the labelling tells me that it is “made from scratch on the family farm…[and that it] offers the best in authenticity, provenance and environmental sustainability”. Further down, in smaller white lettering against a black background, the label informs me that their “classic London Dry style gin has been crafted to make the perfect G&T…a selection of the finest botanicals are distilled into [their] award winning vodka in [their] handmade copper pot stills. Juniper, coriander, vapour infused citrus peel and fresh fruit up front, give way to exotic spices, finishing dry and bitter”. My mouth was salivating as I read this.

Often I find that the enthusiasm of the marketeer for their product does not quite match the reality of the drinking experience, but, fear not, this is a wonderful gin which louches with the addition of a premium tonic, full of vibrant citric notes, slightly nutty and spicy but one that allows the juniper space to play. It was moreish and even with a relatively punchy strength is one where a second glass is hard to resist.

A wonderfully crafted gin in an impressive and thoughtfully designed bottle, what more can one ask for?

Until the next time, cheers!

January 12, 2024

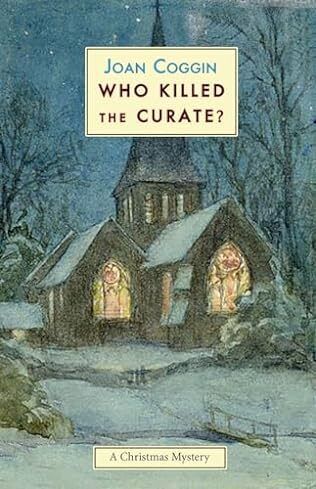

Who Killed The Curate?

A review of Who Killed The Curate? By Joan Coggin – 231210

Joan Coggin, who also went by the name of Joanna Lloyd, is a new crime writer to me. Who Killed The Curate?, sub-titled as a Christmas mystery and set at Christmas 1937, was originally published in 1944 and is now reissued by Galileo Publishers. It is the first of four novels to feature Lady Lupin, the improbable wife of the Vicar of Glanville. It is as much a social satire as it is a murder mystery and, indeed, if the comedic elements were stripped out we would be left with nothing but a slim novella. It is, though, great fun.

Lady Lupin turned her back on her gay social life in London to marry Andrew Hastings, an older man who is a man of the cloth. She is an archetypal airhead, totally socially unaware, lacking any modicum of common sense or concentration. She is apt to say the first thing that comes into her vacuous head. Nevertheless, she makes a determined effort to throw herself into the affairs of the parish, becoming involved with the Girl Guides and the Mothers’ Union with predictable disastrous results. She tries, but her efforts are exhausting and disrupt the previously peaceful rhythms of village life.

She is, though, blessed with the occasional apercu that makes sense out of chaos and is ideal for her to play the role of an amateur sleuth. Whether she realises it or not, her immersion into the affairs of the village means that she is full of information which in more competent hands can be useful. She also believes in being perfectly transparent, her character and lack of self-awareness precluding her from concealing anything, even from the police. In this book, Lady Lupin is the catalyst for investigation and the amateur sleuthing is more of a collaborative effort with her friends, Duds and Tommy Lethbridge, and Jack Scott, something in the British Secret Service.

On Christmas Eve the curate is murdered. Lady Lupin cannot believe that the prime suspect, Diana Lloyd, a writer of detective fiction and children’s stories, could have done it and sets out in her inimitable way to discover the truth. In her maddeningly eccentric and scatter-brained way, she turns out to be a repository of some useful information about the villagers and their psyches which both the police and Scott are able to use to good effect.

It emerges that there was a much darker side to the curate who fuelled his zeal to support the missionary movement with more than a little bit of blackmail. One this fact has been established, the culprit is relatively easy to spot.

The joy of this book, though, is not in the complexity of its plot or in the quality of the deduction. It is a social satire, a comedy of manners with a bit of a murder mystery thrown in, the sort of light entertainment that Channel 5 might air. There is more than a flick of the feather boa in the direction of E F Benson’s Mapp and Lucia. It is perfect for a festive evening and I shall look forward to reading the other Lady Lupin novel Galileo Publishers have reissued, Dancing with Death.

January 10, 2024

As The Days Lengthen, The Cold Strengthens

Once we are past the Winter Solstice, the shortest day or longest night depending upon your point of view, the days lengthen, by around two minutes and 8 seconds a day. The impact is almost imperceptible but as the accretion of extra daylight is cumulative, by the time we get to the Summer Solstice we have gained an extra eight hours and 43 daylight, only to lose it all again as we move once more to the Winter Solstice.

Counter intuitively, though, as the old proverb “as the days lengthen, the cold strengthens” points out, the weather generally gets colder. Statistically, January and February are our coldest months. January 10, 1982 was particularly cold, setting the lowest recorded temperature in the UK, -27.2C in Braemar, and in England, -26.1C at Edgmond, near Newport in Shropshire. A study of average daily temperatures over a period of 130 years revealed that the ten coldest days occurred between January 3rd and February 20th with five occurring between February 13th and 20th.

The records suggest that we should be particularly wary of February 17th, the coldest day with an average minimum temperature of 0.8C and a maximum of 6.7C. However, such is the capricious nature of the British weather that you cannot be certain. While, in 1878, Llandudno was basking in a glorious 17.4C, the warmest temperature recorded for February 17th, a year later the record for the lowest temperature was set, the mercury in Aviemore showing -23.1C.

The reason for this disconnect is all to do with the time it takes for the Earth’s land and water to heat up. Water, which covers around 71% of the Earth’s surface, has a much higher heat capacity than land and requires a lot more heat to raise its temperature. Like the coals of a fire, the Earth cools gradually and even though the days are lengthening, the amount of solar energy the ground receives in the two months after the Winter Solstice is less than what it is losing. When the pendulum begins to swing in favour of heat retention, the soil warms up and the flora and fauna wake up. Spring is on its way.

The balance between the rate at which the Earth retains and loses solar energy, known as the seasonal lag, also explains why our warmer weather, generally, occurs after the Summer Solstice, when the days are already beginning to shorten.

Our forefathers knew a thing or two.

January 9, 2024

Let X Be The Murderer

A review of Let X Be The Murderer by Clifford Witting – 231209

Another name to the pantheon of publishers who are doing their bet to aid the revival of interest in classic crime fiction is Robert Hyde whose Galileo Publishers has reissued three Clifford Witting novels, amongst others, in 2023. X is the Murderer was originally published in 1947 and is the seventh in Witting’s Inspector Charlton series. It is witty and has a clever twist that upends all the reader’s expectations of how the plot is going to develop.

The novel has some of the classic ingredients of the genre, a country house, Elmsdale, and a will that is about to be changed. However, it also has slightly Gothic, if not sensationalist, overtones, starting with a telephone call from Sir Victor Warringham claiming that during the night he was attacked by a pair of luminous, ghostly hands. Despite Detective Sergeant Martin’s initial scepticism, Sir Victor’s standing in the community means that the report is taken seriously and he, together with Inspector Charlton, go off to investigate. However, their attempts to see Sir Victor are thwarted by the other residents of the house.

Resistance is particularly provided by Sir Victor’s son-in-law, Clement Harler, a man whom Charlton takes an instant dislike to, making him want to hit him with something that would hurt. He lives in the house with his second wife, a younger woman called Gladys, and stands to gain under the original will. The long-serving housekeeper, Mrs Winters, no fan of the Harlers, is thought to be the likely beneficiary of any change in the will. The Harlers appear to be making a concerted effort to question the sanity of Sir Victor, a consultation with the ludicrously named eminent psychologist, Sir Ninian Oxenham is planned, a move which if successful would invalidate any change to the will.

What seems a fairly straightforward set up with an inevitable conclusion becomes anything but as the plot unfolds. Yes, there is a murder, but the victim and the circumstances in which it is committed forces the reader to challenge all of their preconceptions. Other characters move into the purview, not least the gardener, Tom Blackmore, and the family solicitor, Mr Howard, who seems overtly friendly and helpful, and a drunkard and blackmailer to boot, Raymond Valentine.

However, the star of the book is another of those precocious children who crop up in crime fiction, the ten-year-old John Campbell, who lives with Mrs Winter, and is the only sign of vitality in a house ravaged by competing factions. His plight, as the story moves to its conclusion, is affecting, but the truth as to his real identity at least ensures that that part is happily resolved. As Charlton digs deeper into the case, he discovers family secrets and hidden identities which help to make sense of what was going on at Elmsdale.

Witting uses his descriptions of the house as a metaphor for what is going on inside. It is in a state of neglect, and the brutality of its architecture is hidden by a façade of ivy. Like the residents inside, it is hiding its secrets under the veneer of respectability.

Structurally, the book is divided into four parts – theorem, hypothesis, construction, and proof – and Witting writes with his usual verve and wit to produce an engaging mystery which is almost a masterpiece of misdirection. It is great fun and I look forward to reading the other two recent reissues.