Martin Fone's Blog, page 60

February 13, 2024

A Remarkable Overland Trek

Built and launched in Liverpool in 1883, the Forrest Hall was a three masted, iron hulled ship, 277 feet long with a gross tonnage of 2.052, capable of carrying over 3,000 tons of coal in her hold. In early January 1899 she set out from Avonmouth Docks to Liverpool for a refitwithout cargo, only ballast, and with a skeleton crew of eighteen including five apprentice sailors instead of its usual complement of twenty-five, towed by a tugboat, the Jane Joliffe.

A ferocious storm force 9 gale blew up and the tug’s captain wanted to return to Bristol, but the Captain of the Forrest Hall, believed to be James Alliss,could not see the frantic signals because of the poor visibility. The tow rope then snapped when they were west of Lundy Island, the two vessels collided and the Forrest Hall lost its rudder.

Despite lowering its two anchors, as night fell on Thursday January 12, 1899, the Forrest Hall was driven by the power of the storm towards Porlock Bay and the low lying rocks off Hurlstone Point. By this time the Jane Joliffe had lost sight of it and as they later found some damaged steering components floating on the water, assumed that it had foundered on the rocks.

Meanwhile, the crew of the Forrest Hall fired off distress rockets at regular intervals in the hope that they would be seen by one of the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) stations along the north Devon coastline. Eventually, Tom Pollard, the local coastguard and landlord of The Lower Ship Inn in Porlock Weir spotted one and sent his son to telegraph the Watchet lifeboat station for assistance.

The storm was so ferocious, though, that the Watchet lifeboat was unable to launch and so another telegram was sent, this time to the Lynmouth Lifeboat Station, received at 7.52pm, reporting that the Forrest Hall was drifting dangerously towards Porlock Weir.

Conditions were just as bad at Lynmouth, with houses, shops and the lifeboat station on the shorefront already flooded, and the crew concluded that they could not safely launch from the harbour. It was then that the coxswain, Jack Crocombe, came up with the idea of taking the lifeboat, Louisa, overland to Porlock Weir which was sufficiently sheltered to allow a safe launch. After all, it was only a journey of 13 miles to be undertaken in one of the worst storms in living memory hauling a thirty-four foot long boat weighting 10 tons up and down Countisbury Hill with its 1 in 4 gradient over some 434 metres and a trek across Exmoor.

Undaunted by the prospects of this Herculean task, over 100 locals, including women and children, quickly assembled, a team of eighteen horses was attached to the lifeboat’s carriage, and the slow ascent up Countisbury Hill began. Some men were sent ahead to widen parts of the track across the moor and two men were assigned the critical task of keeping the lamps alight. The rest pushed the carriage to help the horses to cope with the hill.

At the summit, the first of a number of setbacks occurred; a wheel came off the carriage, fortunately, near the Blue Ball Inn. Some welcome ale was imbibed while the wheel was repaired. As the most difficult part of the task had been successfully accomplished, it seemed, the majority of the volunteers returned home, leaving just twenty, including the lifeboat crew of fourteen, to carry on.

Near Ashton the track was too narrow for the carriage to pass laden with its cargo. The men lifted Louisa off the carriage, manhandled it with the aid of skids through the narrow passage, and then placed it on the carriage once more. The descent was just as hazardous as the ascent, but once this was accomplished they met their next difficulty. A garden wall restricted the width of the lane to such an extent that the carriage could not pass. The problem was resolved by knocking down part of the offending wall.

Even on the relatively flat track between Porlock to the Weir, they found that the carriage was too tall to pass under a tree. Naturally, some of the group simply felled the tree. They finally reached the Weir at 6.30am where, despite being hungry and exhausted, the crew immediately launched the Louisa, and rowed out to the Forrest Hall, a journey that took around an hour, battling through ferocious winds and rough seas.

February 12, 2024

Dancing With Death

A review of Dancing with Death by Joan Coggin – 240102

Well, what a transformation! The last time I met Lady Lupin, in Who Killed The Curate?, she was a ditzy, scatter-brained, former socialite who was trying to integrate herself into parish life as a new bride of the local vicar. Fast forward ten years, although Dancing with Death, now reissued by the admirable Galileo Publishers, was actually originally published three years later, in 1947, she has matured. She is still apt to make a socially gauche comment and her synapses seem far from conventional but there is a less frenetic atmosphere when she appears and what she lacks in intellect, she more than makes up for in intuitnder the terms ive powers.

Another reason why the book, the fourth in Coggin’s Lady Lupin series, is less a social comedy and more a slightly more conventional murder mystery is that Lady Lupin is called in by her best friend, Duds Lethbridge, to help her in a moment of crisis rather than being at the epicentre of the problem. After she decides to come to Duds’ aid, Lady Lupin disappears from the pages for almost half the book as Coggin fills in the backstory of Tommy and Duds Lethbridge’s disastrous house party over the Christmas period.

The house party trope allows Coggin to introduce a motley collection of guests, including Duds’ cousins, the twins Jo and Flo. Under the terms of their grandfather’s will, the proceeds of his large estate go to the eldest, Flo, who was the first of the two to be born. Although Flo has offered to share the legacy, Jo has flatly refused and the pair have become estranged. The atmosphere of the house is not helped by the presence of Tommy’s cousin, Sandy, who spent four years as a prisoner of war and whose demeanour is morose, nor by Henry Dumbleton, Duds’ former lover, and his chatterbox of a wife, Irene. Flo’s husband, Gordon Pinfold, completes the guest list.

The predictable disaster strikes when Jo is found dead in her room, still wearing her fancy dress costume of Carmen, having apparently committed suicide by ingesting diamorphine, which is prescribed to asthma sufferers, of whom Henry is one. But was it suicide and why is Flo confining herself to her room, only seeing her husband and eating her meals in her room? Remarkably she is spared attending the inquest and after the funeral she is whisked away supposedly to London.

Into all of this steps Lady Lupin and sensing a strange atmosphere sets out in her inimitable fashion to understand the reasons for Jo’s death, unearthing a suspicion of blackmail, and some surreptitious comings and goings into Jo’s bedroom around the time of her death. A heart to heart with Flo which reveals some surprising gaps in her knowledge only heightens Lady Lupin’s suspicions. She engages a private detective to cover the London end, principally to discover why a tin of weedkiller was sent to Tommy, and ropes Duds, Tommy, and Sandy to follow Gordon and Flo with surprising results in what is a tale of greed.

There is a twist to the ending of this tale, although an alert reader, sensitive to the possibilities afforded by twins, might not be as astonished as Coggin might have hoped. Nevertheless, she does a good job in maintaining interest and raising the pace as the story hurtles to its denouement.

For me, one of the fascinating aspects of the book was the insights it offered into life in the immediate post war period. Food is scarce and barely edible, drink is scarce and has to be eked out, making the prospect of a successful house party remote, even without a group of seemingly ungrateful and distracted guests. At one point Duds longs for the return of the old established order of the pre-war world, but realises that that world has gone for ever and that she must reconcile herself to the new order. There is more than a hint of wistfulness in the tone of the book.

It is full of humour, sharp observation and is a satisfying conclusion to the Lady Lupin series. I wonder if Galileo Publishers will reissue the middle two books. Let’s hope so.

February 10, 2024

Why Hot Dogs?

Dog meat hit the news recently with the South Korean parliament approving legislation, expected to come into force in 2027, banning the sale and slaughter of dogs for their meat, although the consumption of dog meat itself will still remain legal. Among certain sections of Korean society, mainly the older generations, boshintang, dog meat stew, had been considered a delicacy while the younger generations, more heavily influenced by pervasive Western “culture” consider the practice beyond the pale.

Boshintang – Korean soup that includes dog meat

Boshintang – Korean soup that includes dog meatIs this the end of a repulsive practice or is it another example of traditional foods falling by the wayside as we rush to homogenise what we eat globally? Not being a dog lover and having a slight tendency towards zoophagy, although not as extreme as that exhibited by William Buckland, I am fairly ambivalent.

The thought does strike me, having watched a documentary of the aftermath of the crash of the Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 in a remote part of the Andes on October 13, 1972, that our ability to exercise our tastes in foodstuffs only persists in stable conditions. In extremis, our innate instinct for survival might well mean that cannibalism is on the menu, although a spot of autophagy might be self-defeating.

Still, there are always hot dogs. Some believe that the name of the long, thin sausages was coined because of the practice in late 19th century of filling the sausages with dog meat, echoing the mid-19th century phrase used to describe a sausage, “a bag of mystery”. Others, though, think that there is a more innocent explanation. In the mid-19th century immigrant German butchers in the United States began selling variations of sausages, some of which were long and thin, rather reminiscent of dachshunds, and were called dachshund sausages. To protect sensibilities, they were later known as hot dogs.

There is no definitive answer to the origin of their name nor, indeed, where the food originated, as their alternative names, frankfurters and wieners, suggest. Even the American National Hot Dog and Sausage Council suggests that the argument is too close to call. What is clear, though, is that the modern hot dog is unlikely to contain dog meat, the stuffing of choice being pork.

February 9, 2024

Three Act Tragedy

A review of Three Act Tragedy by Agatha Christie – 240101

Some sleuths in detective fiction take to knitting to help them think through the complexities of the case before them (Miss Silver and Mrs Bradley), others take to a pipe (Holmes) or go to the cinema (Bobby Owen) but Christie’s Poirot, the Belgian sleuth with the finely attuned little grey cells, makes houses with cards or, in this case, with a pack of Happy Families. That one he picks out happens to be of the milkman’s wife, Mrs Mug, happens to be particularly germane to the case.

There are many of the ingredients of a classic murder mystery to be found in Three Act Tragedy, also known as Murder In Three Acts, the eleventh in Christie’s Hercule Poirot series originally published in 1934. There are house parties, a motley collection of guests, a suspicious butler who goes missing, mysterious deaths which look like accidents, the use of an unusual poison, nicotine, which can be distilled from a common or garden product, rose feed, and plenty of twists and turns to keep the reader on their toes. It is great fun, although Christie is more concerned about keeping the plot moving rather than developing her characters who come across as rather lifeless.

The book is structured into three Acts, a homage to the fact that one of the principal characters, Sir Charles Cartwright, is a doyen of the stage. The first act, Suspicion, deals with the aftermath of a dinner party hosted by Sir Charles in Cornwall in which a vicar, the Reverend Babbington, dies suddenly after drinking a cocktail. While the host believes it to have been foul play, the other guests, including Poirot, conclude that it was an accident, especially as no evidence of poison was found in the glass.

That Sir Charles’ suspicions are well founded becomes apparent in the second Act, Certainty, when news arrives in Monaco of another sudden death, this time of Sir Charles’ friend, Dr Bartholomew Strange, who dies suddenly after drinking a glass of port at a party attended by most of the guests of the first event. The third Act, Discovery, deals with the investigations and ultimately the unravelling of motive and the identification of the culprit.

Sir Charles plays a leading role in the investigation, aided by Mr Satterthwaite, who had appeared in various of Christie’s short stories, a flighty all-action young woman, Hermione Lytton Gore, aka Egg, who has a pash for Sir Charles, and, of course, Poirot. To Egg’s dismay Poirot’s preferred approach is to sit back and mull over the intricacies of the case. When he finally bestirs himself, only to find that a supposedly important witness confined to a sanitorium, Mrs de Rusbridger, has also died in mysterious circumstances, and hot foots it down to Cornwall to observe the activities of Sir Charles’ secretary, Miss Milray, he is able to piece the clues together and come up with an astonishing conclusion.

The reader, if they have come to this story for the first time, would be hard pushed to anticipate the motivation for the crimes, even if they had an inkling as to the identity of the killer, and on reading the final pages will probably conclude that it was a preposterous amount of effort to go to when there were other easier and less dangerous ways of resolving a set of circumstances in which the culprit had found themselves. Still, there would not have been a story to tell then. The replacement of the poisoned glasses with clean glasses requires a feat of legerdemain that might just have been possible and the poor vicar, the motivation for whose death baffles even the great Poirot, is little more than the victim of a dress rehearsal. As Poirot says at the end, it could have been him.

While not the best in the Poirot canon, there is much to enjoy in Christie’s storytelling, even if the seams of the plot are in danger of falling apart at times.

February 8, 2024

Chord Of The Week

There was great excitement at the Buchardi Church in the German town of Halberstadt on Monday, February 5, 2024 when the organ playing John Cage’s Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible) changed chord. The composition, being played on a specially built organ, is not set to finish until 2640 and for the first eighteen months of the performance, which began in 2001, there was total silence until the first note rang out. Since then there have been sixteen chord changes.

Volunteers had to add an extra pipe, the seventh, into the mechanical organ to allow the chord change to occur. The previous chord change occurred exactly two years earlier and the next is scheduled for August 5, 2026. A schedule of chord changes appears on the project’s website if you want to book a ticket to witness one of the strangest events in musical history.

I am not sure it will make the charts.

February 7, 2024

The Silent Pool

A review of The Silent Pool by Patricia Wentworth – 231230

Seasoned readers of Golden Age crime fiction will realise the folly of one character donning a distinctive piece of clothing of another, especially when they go out in the dark. In Patricia Wentworth’s The Silent Pool, the twenty-fourth in her Miss Silver series which was originally published in 1953, Mabel Preston makes this fatal mistake and pays for it with her life, found dead in the pool in the garden of Ford Hose, Adriana Ford’s property. They never learn.

Miss Silver, Wentworth’s sleuth with a penchant for knitting, appears at the start of the story for once, consulted by a woman claiming to be Mrs Smith but really the actress, Adriana Ford who suspects that someone in her household is trying to murder her. There have been three disturbing incidents, one where she thinks she was tripped on the stairs, one where she was given a funny tasting mushroom soup, and another when she finds a strange looking pill amongst her sleeping tablets. In her usual way, Miss Silver gives her some sage advice and then promptly disappears from the story until almost halfway through the book.

Adriana has been enjoying poor health and has several impecunious relatives and hangers on living with her, each knowing that they stand to benefit financially if she died. One, Mabel Preston, her old dresser, receives Adriana’s old clothes and even dyes her hair the same colour as her benefactor. At a party she overhears others ridiculing her appearance and storms off in a huff into the night, only pausing to don on Adriana’s coat with its bold black and white checks and emerald stripe. The next morning her body is found.

The death of Mabel crystallises Adriana’s fears that someone is out to ger her and she calls upon Miss Silver to ascertain who it is. There is a second drowning at the pool, this time the victim is Adriana’s adopted daughter, Meriel, after she had been stunned with a blow from a niblick, suggesting that she had some information that was prejudicial to the murderer and paid for it with her life. Of course, there is more than one keen golfer in the household. The keen observational skills of Miss Silver and her keen psychological insights are put to the test as she seeks to uncover the viper in the nest.

This is a rambling, perhaps overlong book with much going on, but Wentworth allows herself the luxury of time to develop an intriguing set of characters. There is the obligatory Lothario, Geoffrey, who is not content with just one extra-marital affair but two and who seems to be a babe magnet. Not unsurprisingly, his dowdy and slightly dotty wife, Edna, is madly jealous of his activities. Jane Johnstone is a newcomer to the house, employed to look after Stella, the young daughter of Star, another of the Rutherford/Ford clan, who is away on an acting tour. Part of the story is told from her perspective and, naturally, she rekindles an old relationship with yet another of the clan, Ninian who is working in publishing. They are all vibrant characters who give the book its colour.

Wentworth lulls the reader into thinking that Julia and Ninian will assist Miss Silver but their part is to provide the love interest and the happy ending. Once the reader realises that, the number of suspects reduces dramatically. At its heart, it is a story of mania and obsession fuelled by greed and Wentworth manages to maintain the tension until the big reveal, which, for some, may come as a surprise.

Her books might be a tad formulaic and there is no real complexity to the plot, but Wentworth does know how to produce an entertaining read and the pace rarely lags. I did miss the interaction between Miss Silver and Frank Abbott, but you cannot have everything. An enjoyable read.

February 6, 2024

A Measure Of Things – Part Fourteen

When an earthquake strikes, it is assigned a rating on the Richter scale. The recent Sea of Japan earthquake was assigned a rating of 7.6, but what does this mean and how much more powerful is an earthquake with a rating beginning with a 7 than one with a six?

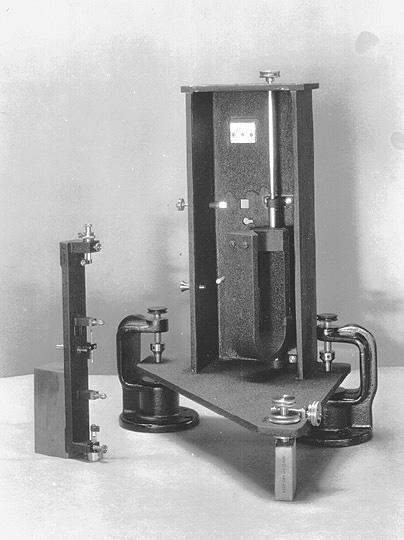

The Richter scale was devised by Charles Richter and Otto Gutenberg in 1935, after the duo collaborated to produce a standardised scale to measure the magnitude of earthquakes. They chose a logarithmic scale to measure the amplitude of seismic waves, information about which was captured by a specific type of seismograph, the Wood-Anderson torsion seismograph. The scale ranges from 1 to 10, although technically there is no upper limit, with each whole number representing a tenfold increase in amplitude and a 31.7 increase in energy release. So, the wave amplitude of an earthquake with a rating of 7 is 100 times greater than a level 5 quake.

While the Richter scale eliminated much of the subjectivity that existed before in comparing earthquakes, the decision to tie it to readings from a specific type of seismograph limited its uptake. Nowadays, however, instruments are carefully correlated with each other and magnitude can be computed from any type of calibrated seismograph. Earthquakes with a magnitude of 2 or below, microearthquakes, are usually only picked up on local seismographs but those in excess of 4.5 are strong enough to be detected by sensitive seismographs the world over.

What the Richter scale cannot do is give an accurate sense of the extent of damage. This is provided by the Mercalli scale, which are expressed in Roman numerals. A low intensity earthquake which produces little in the way of property damage and a sensation of vibrations under the feet would have a Mercalli rating of II, whereas one in which structures are destroyed, the ground is cracked, and other natural disasters are triggered would have a rating of XII.

The appropriate rating on the Mercalli scale, which involves a range of subjective criteria, takes time to establish which is why the more immediately determined Richter scale is more familiar and satisfies the media’s desire to pin a tag on the size of the earthquake.

So now we know.

February 5, 2024

The Case Of The Michaelmas Goose

A review of The Case Of The Michaelmas Goose by Clifford Witting – 231227

One of the three Clifford Witting novels reissued by the enterprising Galileo Publishers in 2023, the Case of the Michaelmas Goose, originally published in 1938, is the third in his Inspector Charlton series. Structurally, it falls into three parts, the lengthy The Goose which is essentially a police procedural as Charlton and his colleagues grapple with the complexities of a death at Etchworth Tower, The Killing which reveals what really did happen and why, and The Golden Eggs which wraps up the tale in a dramatic fashion.

It is perhaps because of this structure that I found this the least satisfactory of Witting’s novels that I had read. It is full of the author’s customary wit and he has assembled a strong and interesting cast of characters, but the way that he has put the tale together with a long and languid opening and a quick fire, very thrilling ending just did not quite work for me.

I like to think that I can piece together the who, what and why from the clues casually dropped into the text, but to have read almost two hundred pages and be almost none the wiser save for realising that there was a change of identity somewhere in the tower, that there was a visitor unaccounted for, and that the murder could not have been done at the tower, only to have the game given away without any compunction in the middle section and the police catching up because of an unforced confession was more than a little unsatisfactory. That sense of disappointment was more than made up by the dramatic denouement where one of the baddies goes down with all guns blazing.

Etchworth Tower, a kind of folly built by the fourth Duke of Redbourn up on High Down, is a local tourist attraction. When the old gatekeeper, Tom Lee, turns up for duty on Sunday, September 29th, he discovers a body of a man wearing a false beard at the foot of the tower. He is later identified as Courtenay Harbord, a young man who is sponging off his aunt but was his death suicide or murder?

Charlton could do with a spreadsheet as he painfully, with the aid of newspaper and radio advertisements, sets out to identify all the visitors to the tower and produce a timetable of their departures around the time that Harbord was spotted at the attraction. The result, a complicated table which is reproduced in full would have been given Freeman Wills Crofts’ imprimatur, reveals tat he can account for 105 of the 106 visitors.

The finger of suspicion is pointed towards Peter Grey, the son of Courtney’s aunt whom Charlton is forced to arrest after a dramatic and unscheduled intervention by the jury at the coroner’s inquest. One thing he is certain of in a perplexing case is that Peter is not the culprit, a feeling that is perhaps prejudiced because he is falling in love with his sister, Judy, and he vows to clear his name. There is no sense of conflict of interest here!

It turns out to be a case of money counterfeiting, two hardened criminals, not unknown to the police, luring spendthrift and impecunious young men into their web of intrigue, and the inevitable repercussions of gang members falling out. Two of the fake notes had already been spotted some time ago and Charlton had investigated them with no result. However, all of this seems to be pulled out of thin air, a piece of legerdemain on Witting’s part that no reader could really second guess. The reader’s perplexity is heightened by the fact that gang members, who are identified by their real names, correspond to characters seemingly masquerading in quiet respectability, whom we met under different identities in the first part. I almost had to create a spreadsheet myself!

Nevertheless, whilst it might have been unsatisfactory as a murder mystery, inverted or otherwise, there is much to admire in what is a witty and entertaining story. A stroke of genius was to include the original illustrations in the reissue. Well done, Galileo Publishers!

February 3, 2024

Gin Galore

The Flying Horse Hotel in Packer Street in Rochdale has recently undergone a refurbishment and reopened for business on February 1st. Nothing unusual in that although a somewhat bold move at a time when the hospitality sector is in crisis.

What is newsworthy is that, according to Ben Boothman the landlord, while Fred – it always is Fred – was smashing out the cellar, he found a bottle of vintage Gordon’s Gin behind some wooden shelving in the walls. Complete, although missing its paper label, the 75-cl vintage gin dates back to the 1950s and has an estimated value of between £300 and £500.

The gin bottle is going to be raffled with the proceeds going to the local Springhill Hospice, with the draw taking place on February 29th.

The pub will also house its own in-house brewery boasting 37 brew lines.

Seems well worth a visit if you are in the area.

February 2, 2024

Inquest

A review of Inquest by Henrietta Clandon – 231223

One of the many noms de plume which the prolific writer, John Vahey, used was Henrietta Clandon. I have not read any of Vahey’s books before and Inquest, originally published in 1933 and reissued by Dean Street Press, is the first he published under the guise of Clandon. It is at times witty, with some sharp observations and the characters are well drawn.

The book’s set up treads very familiar ground, a country house party albeit with a twist. Six months before the book begins a businessman, William Hoe-Luss, had died at his French chateau, having eaten some poisonous mushrooms and then falling down some stairs. The French officials acted quickly, ruling that it was accidental, that the mushrooms were the principal cause and the body was cremated. There are suggestions, though, that all was not as it seemed and his widow, Marie, who was the principal beneficiary from William’s demise, invites all who were at the chateau at the time to her country house in England at Hebble Chase to rake over the coals. A sort of inquest, you might say.

The story is narrated by Hoe-Luss’ physician, Dr Soame, the only member of the party who was not present at the chateau. He accidentally lets slip that the botanist in the party, Hector Simcox, is adamant that the type of fungi believed to have poisoned Hoe-Luss was not to be found growing on his French estate. Not long afterwards, Simcox too plunges to his death, having fallen from a window while apparently looking at some lichen on the house’s wall. Was it an accident or a murder and had his suspicions forced the killer to strike again?

It is interesting to see how different writers approach a similar subject. In some ways Inquest is a bit of a forerunner to Freeman Wills Crofts’ Mystery on Southampton Water, published a year later, in the back story which involves the discovery of a revolutionary manufacturing process, industrial espionage, and the fortunes of two companies. As is his wont, Wills Crofts plunges headlong into the nitty gritty of his case while the machinations of the two competing businessmen, Hoe-Luss and Caley Burton, the latter a guest at both the chateau and Hebble Chase, gradually emerge as if by osmosis.

The reasons for the difference in handling are twofold. Clandon chooses to make Dr Soame his narrator. While he does his own sleuthing, principally at the behest of Marie, he is on the periphery of the police investigations, principally relying on his position as police surgeon and his good relations with the Chief Constable, Tobey, and Mattock of the Yard to get any sort of insight into the direction and progress of the official investigations. Secondly, the British police have no official jurisdiction over Hoe-Luss’ death and have to concentrate on Simcox’s fall, a handicap that forces them to attack the kernel of the mystery from an oblique angle. These two structural problems weaken the book as a murder mystery with too much going on off stage for my taste.

Nevertheless, there is much to enjoy in the book where a stained dress shirt, a fibre from a face flannel, and the wrist actions of a polo player and an accomplished angler have important parts to play in a house which has convenient passageways to allow guests to move around unobserved. There are only two, three if you are stretching the point, credible suspects, but mainly through a notable parsimonious approach to sharing vital information, Clandon maintains the mystery until the end. Whether the rationalisation of what happened is enough to convince the jury is another matter.

However, for me the strength of the book is in Clandon’s writing, the characterisation and wit. The other three Dean Street Press reissues have joined my TBR pile.