Martin Fone's Blog, page 124

May 3, 2022

The Eye In The Museum

A review of The Eye in the Museum by J J Connington

The bane of the modern criminal’s life is the ubiquitous eye of the CCTV system. The Eye of the Museum, originally published in 1929, features an early version, the camera obscura, which takes pride of place at the top of the Struan Museum, a little visited collection of bizarre objects including a glass eye, which is the pride and joy of the caretaker, Jim Buckland. It throws on to a white table images from the streets and the surrounding areas. Buckland is fastidious in his use of the machine, thinking that it would be an affront to the spirit of Mr Struan if he used it to spy on the town’s residents. However, he is in the habit of switching it on while he is locking up and just happens to see some goings on which confirm Superintendent Ross’ suspicions and leads to an arrest.

The problem with a camera obscura in comparison with CCTV is that it does not leave a permanent image and so Superintendent Ross, the detective leading the investigation, who has made a big thing about collecting evidence yourself if you want it to be reliable, has to rely on the word of Buckland to bring the case to its conclusion. Whether it would be strong enough to lead a jury to convict is doubtful, but it is the final piece in Ross’ jigsaw rather than the lynchpin.

Connington decided in this book to give his faithful duo, Sir Clinton Driffield and “Squire” Wendover a rest. They do not appear, despite what the blurb to some editions may suggest. I missed their repartee, Wendover’s ridiculous snobbery, and Driffield’s rather arrogant low regard of the “Squire’s” intellect and investigative prowess. Ross is an altogether different kettle of fish. He is serious, single-minded, a relentless pursuer of the truth but, for me, is a bit of a cold fish, a character that is hard to warm to and about whom we learn surprisingly little, save that he is a fan of Swiss Family Robinson and brings his culprit down using a technique from the pages of that children’s classic.

The plot treads a well-worn path, featuring a wealthy, cantankerous woman, this time a gambler and an alcoholic to boot, Evelyn Fenton, who under the powers of a restrictive will, which seemed to be all the rage in those days, has the power to direct the life of her niece, Joyce Hazlemere. Joyce wants to marry Leslie Seaforth, but neither have the funds to do so. In the garden of the museum, which they visit in the first chapter, they discuss the prospect of Evelyn’s death. It comes as no surprise that soon afterwards, Evelyn is found dead.

Her doctor, Dr Platt, is sceptical that her heart just gave out and at the subsequent post mortem it is confirmed that she had been poisoned, although her demise had been hastened by the application of slight pressure to her vagus nerve. Joyce is the prime suspect, but Seaforth and his boss and family solicitor, James Corwen, are determined to fight her corner. Ross, initially, finds the two a tad uncooperative but is alert enough to realise that Corwen is drip feeding him information which may prove to be enormously helpful.

There are the usual mysterious visitors to the house around the likely time of Evelyn’s murder, including her estranged husband and her supposed lover, Dr Hyndford. There is a psychological aspect to the story which is hinted at earlier, but which comes to the fore as the story reaches its climax.

Ross finds a trail of IOUs and insurance policies which, with the help of an amateur graphologist, are not what they seem and shed light on the motivation behind the murder. With relatively few suspects to consider and with the method of murder requiring specialist knowledge, it is not difficult to work out who the likely culprit is, especially as there is another murder to eliminate a suspect, a twist that does not serve to confude but to clarify the reader’s thoughts.

Ross gets the culprit at the third attempt after a boat chase and the case for the prosecution, in the form of a detailed exposition of the evidence with sources, forms the penultimate chapter. It was an engaging enough read, the plot was well-thought out and developed, as is Connington’s wont, but Ross is too anodyne a figure to raise it to the heights of the best of the Driffield novels.

This is one for the completists, rather than one for those wishing to dip their toes into Connington’s oeuvre.

May 2, 2022

Walworth’s Zoo

Albert Cops with his menagerie in the Tower of London was not the only entrepreneur to pander to the public’s desire to see exotic animals. Perhaps London’s strangest menagerie was to be found, bizarrely, on the rickety upper floor of Essex Exchange, on the northern side of the Strand. Founded in 1773 by the Pidcock family, initially as the winter quarters for the animals in their travelling circus, it soon proved a popular tourist attraction.

Running around the room in front of walls daubed with exotic scenery was a series of caged dens containing lions, tigers, jaguars, tapirs, and even, testing the strength of the floorboards to their maximum, several pachyderms. Higher up the walls were enclosures for birds and monkeys. The roars of the animals could be heard in the Strand, often startling the passing horses.

Edward Landseer and Jacques-Laurent Agasse painted the animals while Lord Byron was charmed by the menagerie’s elephant, Chunee. It “took and gave me my money again”, he noted in his diary for November 14, 1813, “took off my hat – opened a door – trunked a whip – and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler”. While the panther, he opined, was the “handsomest animal on earth”, the “poor antelopes were dead”.

It was renamed the Royal Grand National Menagerie when Edward Cross acquired it in 1814, and, in a clear nod to the rival establishment at the Tower, he employed a doorman dressed as a Yeoman of the Guard. Admission was a shilling, group tickets a florin, while admittance to feeding time, at nine in the evening sharp, cost half a crown.

Chunee, was the star attraction, taking up residency in 1809 and regularly parading on the streets and appearing on the stage, including a forty-night stint at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. However, there is only so much an elephant can bear and on February 26, 1826, Chunee went berserk, killing his keeper. It took three days, a civilian firing squad, soldiers from Somerset House, a small cannon and 152 balls of ammunition to put him out of his misery.

Chunee’s demise led to public outrage, attendances plummeted, and, to add to Cross’ woes, the Essex Exchange was demolished in 1829 as part of the redevelopment of the Strand. He moved his menagerie to King’s Mews, now the site of the National Gallery, sold some of his animals to London Zoo and the rest, in 1831, to the Surrey Literary, Scientific, and Zoological Society, which he had founded, for £3,500.

The Society, under his direction, created Surrey Gardens on eighteen acres of parkland in Walworth. It boasted promenades, spectacular gardens, laid out by Henry Phillips, firework displays, balloon rides, and re-enactments of historical events such as the eruption of Vesuvius and the Great Fire of London. At its height upwards of 8,000 people attended a day, happy to pay their shilling admission. Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children visited in 1848.

Surrey Gardens also housed a zoo, now long forgotten, which in its pomp was home to 170 species. At its centre was a large, circular, domed, glass conservatory, a precursor to the Crystal Palace, in which exotic fish, birds, and animals were displayed. Feeding time was a particular draw, and the keepers were not averse to teasing the animals to guarantee “a good show”. It was also the home to five giraffes, the first to be publicly displayed in Britain, which were transported from Africa in 1843 and walked from the docks to Walworth at night so that residents were not disturbed by “these strange horses”.

Cross’ death in 1854 hastened the Garden’s end. The animals were sold off in 1855 to fund the building of a 12,000-seater music hall which burnt down in 1861, and the park was sold to property developers in 1877. The ghostly cries of the animals, it is said, can still be heard today.

May 1, 2022

Record Of The Week (6)

<> on October 27, 2015 in Whitby, England.

" data-medium-file="https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=300" data-large-file="https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=474" src="https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=780" alt="" class="wp-image-18288" srcset="https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg 780w, https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=150 150w, https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=300 300w, https://windowthroughtime.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/dracula.jpg?w=768 768w" sizes="(max-width: 780px) 100vw, 780px" />“White face, black shirt/ White socks, black shoes/ Black hair, white strat/ Bled white, died black”, sang Ian Dury on Sweet Gene Vincent. Well, if you have black shoes, black trousers or skirt, a white shirt, waistcoat, and a black cape, make your way to Whitby Abbey on Thursday 26th May for 6.45pm.

To mark the 125th anniversary of the publication of Bram Stoker’s novel, English Heritage are launching a bid to break the Guinness World Record for the largest gathering of people dressed as vampires, currently standing at 1,039, set by an event organised by Ed Kuhlmann in Virginia in 2011.

Fangs on the upper teeth are compulsory, pallid skin helpful, and a menacing demeanour optional. Cloves of garlic and crosses are not welcome.

Sounds fun and it would be fitting if the record was broken at the place that inspired Bram Stoker.

April 30, 2022

Toilet Of The Week (32)

With public toilets as rare as hen’s teeth these days, it is gratifying to record that a reconditioned carsey has recently opened its doors to the public. It is situated in Sandown Bay on the Isle of Wight by the rather splendid Victorian fort perched atop of the cliffs, known as Sandown Barrack Battery.

More specifically, and fittingly, it is behind the National Poo Museum, a micro-museum which displays the faeces of animals around the world. The museum is interactive, with the exhibits sealed in resin spheres which can be handled. You do not have to spend a penny to get in, although donations, monetary, of course, are welcome.

The toilet closed in 2011 and was looking rather sorry for itself. It was a challenge that the members of Eccleston George, the moving forces behind the museum, found too difficult to resist. They have lovingly restored it and rather splendid it looks too. Described as the National Poo Museum’s Super-Loo it is now open for business and, according to one grateful visitor, “it’s like stepping into Narnia”.

Next time I am in the area, I will be certain to pay it a visit.

April 29, 2022

Twenty-Four Of The Gang

Another colourful piece of slang that referred to a contemporary event whose notoriety has faded into the mists of time is Harriet Lane, a reference to Australian canned meat. It was so called, James ware avers in his Passing English of a Victorian Era, because of its unedifying appearance akin to chopped up body parts.

Harriet Lane, the mistress of Henry Wainwright, a brush maker, was murdered by him in 1874 and her body was buried in his warehouse. The following year, Wainwright was declared bankrupt. He disinterred her body and with the assistance of his brother, Thomas, and another brush maker, Alfred Stokes, sought to rebury her elsewhere. Stokes was suspicious of the packages he was handling, opened one up, saw it contained body parts, and notified the police.

At the subsequent trial, Henry was found guilty of murder and was hung on December 21, 1875, while Thomas was found guilty of being an accessory after the fact. I think I will give a can of Harriet Lane a miss. Perhaps I would be better off having a hasty pudding. This was a piece of Victorian fast food, consisting of flour and water, boiled for five minutes.

I know several people about whom I could say he never does anything wrong, a satirical musical hall phrase used to describe someone who can never do anything right. They are almost as bad as someone who worships his creator, said of a self-made man who thinks a lot of himself. Such terms of opprobrium may be assuaged if they had a heap o’ saucepan lids, rhyming slang for money via dibs.

More slang anon.

April 28, 2022

Postscript To Poison

A review of Postscript to Poison by Dorothy Bowers

The moral of the story is if you are a cantankerous old woman despised by all, do not announce that you are going to alter your will. It never ends well. And, P.S, if you are planning the perfect murder, do not be tempted to make some final embellishments. They will be your undoing.

Postscript to Poison, Dorothy Bowers’ debut crime novel, originally published in 1938 and now reissued by Moonstone Press, is an impressive and enjoyable piece of work from an author I had not come across before. What the story may have lacked in intricacies of plotting, it more than makes up for in the quality of Bowers’ writing and, particularly, her sharp characterisations. Often the reader can be overwhelmed with characters barely indistinguishable from each other. Here, though, Bowers, takes care to draw each of her principal protagonists, such that even when they disappear from the narrative for a while, their characteristics, habits, and foibles stay with you.

Bowers also has a profound sense of place and nature. Her descriptions of Minsterbridge and its weather fall just the right side of purple prose, giving an added dimension to a tale that is told with vigour and a sense of purpose, the reader provided with enough information to understand what is going on, but not bogged down with unnecessary detail. She also plays fair with her readership, the clues needed to solve whodunit are sprinkled throughout the story.

Chief Inspector Pardoe of Scotland Yard, her go-to detective in Bowers’ series of five murder mysteries, is an intriguing character. He is human enough to be irritated that a new murder case has led to him having to delay a well-earned holiday in the Cotswolds, but earnest enough to throw himself into the investigations with gusto. Behind his urbane, polished exterior is a steely determination to see justice prevail. He is a character the reader can warm to, neither too bogged down in details to make following him a chore nor too intuitive to leave us scratching our heads. I shall be interested to see how his character develops.

By the standards of so-called Golden Age murder mysteries, the plot is both a little mundane and hackneyed. Cornelia Lakeland is a dictatorial old woman, who rules over the household at Lakeland with a rod of iron, making the lives of her step-grandchildren, cousins Jenny and Carol, a misery. They will lose the prospect of inheriting their share of the family fortune if either take jobs or get married without her permission. Her companion is worried about the prospects of a legacy and the staff of the house have their own reasons for wishing for the old woman’s demise. There are motives aplenty for Pardoe to get his teeth into.

Having been ill for most of the summer, Cornelia is now well enough to go downstairs. The first thing she arranges is for an interview with her solicitor, Rennie, with a view to altering her will. During the night before the meeting, she falls ill and dies. The post-mortem established that she was poisoned. A series of anonymous letters point the finger at the Doctor, Tom Faithful. Jenny’s beau, a Polish film star, was let into the house that evening. A mysterious stranger was seen lurking around the house.

The maids hold the key to unravelling the mystery. Emma returns some of Cornelia’s letters which she had stolen and a piece of bandage found on the body of Hettie, murdered for what she might have overheard, confirm to Pardoe what has been going on n the house. In a dramatic finale, in which the good Chief Inspector, is injured, the arrest is made.

I found it an entertaining read and will follow Pardoe’s adventures with interest. Bowers is a writer well worth looking up.

April 27, 2022

The Case Of The Bonfire Body

A review of The Case of the Bonfire Body by Christopher Bush

Christopher Bush had a long and prolific writing career, publishing sixty-three adventures featuring his amateur sleuth, Ludovic Travers, stretching from 1926 to 1968. I am following the series in chronological order and The Case of the Bonfire Body, also going by the title of The Body in the Bonfire, is the fifteenth, originally published in 1936 and reissued by Dean Street Press. This is one of the better books in the series with Bush excelling himself in developing a mystery which twists and turns and leaves the reader in doubt as to whodunit until the end.

Seasoned Bush aficionados will recognise his habit of introducing seemingly random and unconnected events into his stories, often towards the beginning of the tale and sometimes in the form of a prologue, the relevance of which only becomes apparent as the solution unfolds. Travers’ glee at securing a rare Limerick Crown and his encounter and act of generosity towards a match-seller down on his luck are cases in point. Bush is also not averse to showing Travers’ human fallibility. He is not an omniscient sleuth. In this case the solution is staring him in the face, but he does not have the wit to realise it until much later on.

One of the delights of the Travers series is the amateur sleuth’s relationship with the “General”, Wharton of the Yard. They work well together, sparring off each other, Wharton’s feet firmly planted on the ground while allowing Travers to engage in his flights of fancy. Bush takes time to develop Wharton’s character in this story, and the effort pays off, giving some human warmth to what might otherwise have been a grisly story.

Death, obviously, is central to murder mystery stories, but in the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction the murders tend to be inventive and frequent, but rarely linger on the goriness of the body. I have always wondered whether the horrors of the First World War were still raw in the contemporary readership. They wanted entertainment, the intellectual challenge of working out what happened, but were not too keen to have the goriness of the business brought into their front room, thank you very much. Here, though, Bush bucks the trend.

A body is found in a bonfire, the head, and hands brutally hacked off, and he does not spare the details in a vivid portrayal in what is an excellent opening to the story. In London a doctor is found stabbed to death in his surgery at around the same time, with suggestions too that he may have committed murder. Are the two cases linked, why and how?

After such a great beginning, there is an air of inevitability that the pace drops as the investigations get mired in theorising as to whether three people are involved in what is a case of the consequences of thieves falling out or whether there is a mysterious fourth person, dubbed X. It is difficult to write much about the the case without giving the game away. Suffice it to say that there is more to matters than meets the eye and not everything is as it appears to be. A down and out fished out of the Thames with Travers’ missing Limerick Crown secreted in his boot opens the sleuth’s eyes to what is going on.

The book ends with Bush in fine form and while for the purist the intricacies of the plot rely too much on requiring the reader to suspend belief, it is an enjoyable piece of entertainment and well worth a read.

April 26, 2022

A Murder Is Arranged

A review of A Murder is Arranged by Basil Thomson

The eighth and last in Thomson’s Inspector Richardson series, A Murder is Arranged was originally published in 1937 and now reissued by Dean Street Press. I have found the series variable in quality but at least Thomson rounds off the Richardson saga in some style, albeit in his usual understated fashion. He died in 1939 and there is no sense in the text that this was going to be the last we would see of Richardson. I wonder, had he not died whether he would have written any more.

Richardson, from his elevated position of Chief Constable, once more directs operations, offering advice, tactical direction, but leaving his underlings, principally Inspector Dallas, to do the not inconsiderable leg work. Thomson takes the unusual step of deploying the lengthy progress reports that Dallas files to drive the narrative forward, interspersed with third party narrative of events that fall outwith the police investigation at the time. It may seem an odd approach, and the stilted officialese of the opening of each report can seem a bit stilted, but it seems to work. Thomson was a career policeman, heading up Scotland Yard’s CID section during the First World War, and the reports give some verisimilitude to the grind that is police work.

Some familiar themes can be found in this gripping tale which boasts a plot more intricate than Thomson’s standard fare. It is once more a story featuring Anglo-French police co-operation. Long gone, thankfully, is the little Englander attitude that so marred The Case of the Dead Diplomat, although Thomson cannot resist pointing out the differences between the two forces’ interrogation techniques and French officialdom’s susceptibility to a bribe. Dallas and Richardson, instead, are conscious of the expenses being racked up by Dallas’ sorties to France, but the two forces work well together.

Once again there is a mix of murder and robbery and a fashion house, themes those who have read Thomson will recognise. In essence, this is a country house murder mystery with a twist. Forge, the owner of Scudamore Hall, has, somewhat bizarrely, invited a motley crew of guests whom he has picked up in various hotels to celebrate Christmas with him. One, Margaret Gask, is found shot dead on Crooked Lane, the driveway to the stately pile, her mink coat has gone missing, and an infamous receiver of stolen property, Fredman, who appears to be associated with Gask, is also found murdered.

It appears that Forge’s guests are not as random as first appeared, each having their own particular reasons to avail themselves of his hospitality. Not everyone, including Forge’s staff are all they appear to be and we soon enter into a world of jewellery thieves, fences, fake monks and Italian prince, a murdered French senator, a Parisian fashion house which keeps losing its stock, false identities, duplicated car registration plates, metal boxes, a monastery used as a safe haven for stolen goods, and much more as investigations take place on both sides of the Channel.

The plot twists and turns until it reaches its inevitable conclusion. The police only have evidence strong enough to convict someone for the murder of Fredman, but that is enough. You can only hang once. Revealingly, there is a moral line in the world of the felon between good, “honest” robbery and dirty murder, a line that gave rise to the book’s alternative title, When Thieves Fall Out, The crossing of that particular Rubicon hastens the resolution of the case.

Thomson tells the story with workmanlike, honest prose which moves the story along, although there is little in the way of variation in pace and tone. It has its moments of humour and is an entertaining insight into police investigations and inter-force cooperation. It provides a good note to end a series that was worth persevering with.

April 25, 2022

The Lion Tower Of London

Founded in April 1826, the Zoological Society of London brought to fruition the dream of Sir Stamford Raffles, Humphry Davy, and Joseph Banks, to create a zoological collection that would not only “interest and amuse the public” but also rival that of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. A plot of land was purchased from the Crown in Regent’s Park, animal houses were constructed, and on April 27, 1828, what is now ZLS London Zoo opened its doors to members of the society. It is the world’s oldest scientific zoo, but, curiously, members of the public were only allowed entry in 1847, their ticket money boosting the Society’s depleted funds.

For centuries keeping exotic animals was the preserve of royalty, often given as diplomatic gifts. In 1110 King Henry I built a seven-mile-long wall at the Royal Park of Woodstock in Oxfordshire to enclose a collection of lions, camels, and porcupines, in what was England’s first zoo. The animals were kept not to satisfy any scientific interest, but to add some spice to the king’s passion for hunting.

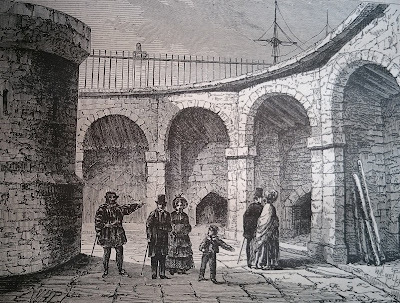

A gift of three lions from the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, in 1235 prompted Henry III to create his own menagerie, which included a polar bear, allowed to fish in the Thames, and, in 1255, an animal which the contemporary chronicler, Matthew Paris, described as “a rough-hided animal that eats and drinks with its trunk”. By the 1270s Edward I had built a tower, known as the Lion Tower, at the entrance to the Tower of London, known as the Lion Tower, to house the royal animals, their roars intimidating all who passed by.

Keeping elephants was especially problematic. They were thought to be carnivorous, while James I was advised to feed his on a diet of wine between the months of September and April. This woeful ignorance of their dietary requirements, together with cramped living conditions and the extremes of the English climate, meant that the animals often lived short, miserable lives.

The public was first admitted to see the collection during the reign of Elizabeth I, for free, if they brought a cat or dog, which were promptly fed to the carnivores. By the start of the 19th century, admission cost a shilling and visitors were advised “not to approach too near the dens, and avoid every attempt to play with them”, sensible advice that was not always heeded. On February 8, 1686, Mary Jenkinson was savaged to death while patting the paw of a lion.

By the time that Alfred Cops was appointed head keeper in 1822 all that was left of the collection was a handful of animals. He set about improving the animals’ living conditions, introducing a breeding programme, and extending the collection. There were around 300 animals, representing sixty species, by 1828, and some were even born in the Tower, prompting one commentator to note that “those whelped in the Tower are more fierce than such as are taken wild”.

Despite Cops’ success, accidents and escapes dogged the menagerie. Some wolves broke into a keeper’s apartment, causing his wife and children to flee for their lives, a secretary bird regretted its decision to poke its head into a hyena’s enclosure, and a battle royal between two tigers and a lion, accidentally let into the same cage, resulted in the lion dying from its injuries. With the new zoo at Regent’s Park offering alternative accommodation, the government, tiring of the problems associated with the menagerie, transferred many of the animals there.

Cops, though, was allowed to exhibit his own animals, but even then, misfortune dogged him. His menagerie was closed down on August 28, 1835, after an audacious attack by a monkey on a guardsman. The collection was sold to an American showman, Benjamin Franklin Brown, and the tower was demolished shortly afterwards.

April 24, 2022

Error Of The Week (14)

Where do you stand on artificial grass? From an environmental perspective due to its high plastic content, it should be stamped on, but its proponents argue that it is labour-saving. Once down, you do not have to cut it.

Tell that to South Somerset Council. A motorist, Nigel Castle, was so perplexed when he saw a council employee cheerfully deploying a strimmer on a roundabout in Yeovil laid with artificial grass that he got his daughter to take a photograph.

The problem, it seems, was that some pesky weeds had grown through the plastic and the employee was trying to cut them down. As well as potentially damaging the skin, waving a strimmer at them would have no lasting effect. They would need to be weeded by hand and taken out by the roots.

While weeds seem to be the new trendy plants and are to be encouraged, the Council want rid of them and have recognized that their employee was not going about the task in the right way. They admitted that more training was required.

For Castle, though, only ripping up the turf and planting some real grass will do. He has a point as the turf in the picture looks shocking.

Happy Easter!