Martin Fone's Blog, page 123

May 13, 2022

Twenty-Six Of The Gang

If you are looking for a different form of profane expression with which to vent your anger or frustration, why not try Lady in the straw. This was a popular oath and refers to the Virgin Mary who gave birth to her child in a stable. I think it is due a renaissance. And if you want to express your exasperation, how about leave them to fry in their own fat, an alternative to give him enough rope and he’ll hang himself?

Someone’s halitosis getting you down? Try lend us your breath to kill Jumbo. And looking for another way to call out someone’s humbug? Leather and prunella, according to James Ware in his Passing English of a Victorian Era, was a corruption of lather, being whipped cream, and prunella, a sort of damson puree or plum jelly. It was initially used to denote flimsiness and by extension humbug.

London ivy was a pleasing euphemism for dust as it sticks to everything while London smoke described a yellowish-grey colour, popular as a paint colour as it hid the dirt. Making the best of everything and the desire to battle through adversity was known as best side towards London. It also reflected the desire of country folk to see London for themselves and even make their fortune. Its streets were not paved with gold, Ware sagely noted.

A long pull was something to be sought after, an over full measure of drink, either served by the publican as a favour or to attract trade. Either way, I am sure it was gratefully received. Unsubstantiated reports of such a custom may have been a long-tailed bear, an euphemism for a lie as bears do not have tails. If the barman was serving overly generous measures, the landlord may have looked through the fingers, an Irish phrase meaning to pretend not to see.

May 12, 2022

Kyrő Pink Gin

In England all the best ideas are hatched in a pub. In Finland, it would seem, are laid in a sauna. While drinking rye whisky in a sauna, a group of friends began pondering why rye whisky was not distilled in Finland. From that seed of an idea the Kyrő distillery was created. As well as whisky, they distil liquors and gins, including their Pink Gin.

Rye as a base for the spirit that goes to make a gin may seem an odd choice because of its temperamental character, but right from the outset the Kyrő team decided that they would use 100% Finnish wholegrain rye, a distinction that gives them an edge in the marketing of a product in the crowded marketplace spawned by the ginaissance.

Sustainability is another key feature of the Kyrő brand. Their distillery makes use of locally produced bio gas, which uses fish and pork processing waste as a raw material. They reuse any hot water used in the distilling process and aim to heat their facilities and neighbouring buildings with it. Side-streams from the production of alcohol are used to feed local cattle while methanol and other higher alcohols are fed to the bacteria in the nearby sewage farm to keep the local water cleaner. All very laudable.

Pink gin is not normally my go-to kind of gin. It is normally made in the same way as other gins, but post-distillation red and pink produce, spices, or bitters, or even, heaven forbid, added colouring and sweeteners are infused into the spirit. Popular ingredients to be used in the manufacture of pink gins are strawberries, raspberries, rhubarb, grape skins, rose petals, and red currants, all of which have a dual purpose of adding colour and sweetness to the drink and downplaying the heavier, drier, more bitter, and spicier flavours of the botanicals we classically associate with gin. The yin to the yang of London Dry Gin, you might say.

Why I tend to give them a swerve is that I generally find them too sweet for my palate. Here, though, while using strawberries, lingonberries, and rhubarb to provide the sweetness and colour, the team at Kyrő have carefully selected spicy and herbaceous botanicals to produce a well-balanced, creamy, pale pink drink which would be a delight to sip on a warm summer’s evening. And with an ABV of 38.2% a second glass is almost irresistible.

Kyrő Pink Gin comes in 50cl bottles which are dumpy, with squat, broad shoulders, and a short neck, leading to an artificial stopper. The labelling has a minimalist and modern feel about it with black and goldy bronze lettering against a white background. The information about the gin is printed vertically running from top to bottom which means you have to hold the bottle sideways to read the print which was too small for my rheumy eyes.

For a pink gin, it was impressive and for many reasons is worth seeking out.

Until the next time, cheers.

May 11, 2022

Brazen Tongue

A review of Brazen Tongue by Gladys Mitchell

For those of us who like to follow an author’s series in chronological order, it is always a little disappointing when the next one is not available. The irony of Printer’s Error, Gladys Mitchell’s tenth in her Mrs Bradley series, originally published in 1939, not being available in anything like an affordable version – £1,183.99 anyone? – was not lost on me and so I had to move on to the eleventh, Brazen Tongue, published the following year. Bradley’s books are much more stand-alone affairs than those of other series authors with little in the way of on-going character development and so I consoled myself by thinking that I was not going to lose too much.

It was with some trepidation that I picked up this book. Mitchell’s stories are always challenging. Not for her is the well-worn path of murder, some sifting of the clues and the arrest of the butler. Her stories are denser, inverting and twisting the genre to suit her purpose, and leaving her readers with puzzles which at their best test their mettle and often result in a conclusion which was difficult to see coming. Mitchell described the book in an interview in 1976 as a “horrible book” along with Printer’s Error and it is easy to see why. Its ending is unsatisfying, leaving too much in the air, not providing the clarity that the reader expects from novels of this type. Of course, life is like that and, in reality, many a crime investigation results in an outcome based on probabilities rather than cast iron certainty.

The dissatisfaction I ultimately had with the book also stems from Mrs Bradley’s wonky moral compass. She is fearless and indefatigable in pursuit of the truth, but less so in seeing that justice prevails. It leads her to some odd moral and, dare I say it, class-based choices where it is all right to turn a blind eye to the activities of a young ambitious thing while seeing a working-class man pay for what he might have done.

The book is set in the early days of the Second World War, the so-called phoney war, and for the modern reader there are many fascinating insights. Windows are blacked out, the Air Raid Patrol wardens and volunteers are working at a newly opened Report Centre, air raid sirens sound, and petrol is in short supply. George, Mrs Bradley’s man, has to resort to syphoning off petrol surreptitiously to have enough to drive her to an appointment and is aghast at the suggestion that he coasts down a hill with the engine off to conserve fuel. Mitchell feels it necessary when describing what is on the menu to remind her contemporary readers that rationing was not yet in force. The only jarring moments come in the portrayal of the Jewish couple, the Councillor a lazy stereotype and the wife given an unnecessary comic accent.

The little town of Willington is rocked by three murders, all committed within the space of twelve hours. The body of a woman, dressed in a night gown, is found in one of the newly erected water cisterns, a courting couple find the body of a prominent councillor, Smith, propped up in the doorway near the cinema, and a girl working at the report centre, Lillie Fletcher, who has gone out to meet her ominously named beau, Derek Coffin, is found with her head bashed in. The case of the drowned woman is particularly perplexing as she met her end in the nearby river rather than the cistern and no one seems to know who she is.

Is there something that connects all or some of these murders and, if so, what, and whodunit? These are the questions that occupy Mrs Bradley, ably assisted by Inspector Stallard, her niece, Sally, and a young reporter, Patricia Mort, seek to establish. The lives of all who seem to have knowledge of what was behind these murders, including Mrs Bradley herself, are in danger and there a number of failed attempts to silence them. By the end of her investigations, Mrs Bradley seems to have a convincing rationale for what had gone, but just as the reader sinks back into their chair, preening themselves on their perspicacity, Mitchell decides to throw all the pieces of the jigsaw into the air once more, see where they land, and make another pattern from them.

It is hard to give a convincing explanation why she does this. Was she dissatisfied with the initial conclusion or interested in seeing how many more or less convincing resolutions she could construct from a set of circumstances? I think that Mitchell is having enormous fun at the reader’s and the genre’s expense. There is a levity, a quiet whimsy, to her writing style and she has tremendous fun along the way, constructing characters whose names may be pieces of nominative determinism and, in the Rat and Cowcatcher, comes up with a boozer with which Brian Flynn would have been proud.

Brazen Tongue is not for the faint hearted nor the Mitchell neophyte, but if you are a fan of Mitchell’s work you will find much to enjoy in it.

May 10, 2022

The Bath Mysteries

A review of The Bath Mysteries by E R Punshon

I am glad I use my bath to store my coal rather to cleanse myself in as this is yet another murder mystery where the victims, and there are a few of them, drown in their baths. More intriguingly, each of the victims is estranged from their family and friends and has had their lives insured for £20,000, the modern equivalent of just under £1.5m. Worse still for up-and-coming police detective, Bobby Owen, in this his seventh adventure, originally published in 1936 and now reissued by Dean Street Press, the victim who kicks off this story is from his family circle.

Bobby Owen is from an upper-class family, something that he is reluctant to draw attention to and which causes him some difficulties in his chosen line of work, policing. To his chagrin, he is dragged into investigate the death of Ronnie Oliver at the behest of his uncle, Lord Hirlpool, who has pulled a few strings given that he is pally with the Home Secretary. Initially, this is an officially sanctioned frolic of Owen’s own, greeted with the dismay and head shaking of his superiors, but he unearths such a complex web of dodgy financial syndicates, including the wonderfully named Berry, Quick syndicate, life insurance policies and insured lives who have died in seemingly accidental circumstances that the PTB (powers that be) soon take an interest and almost sideline the ambitious ‘tec.

Punshon brings a wide range of characters into his tale from all strata of society, but it is clear that his interest and sympathies lie with the down-and-outs, the poor souls who are condemned to a life of living hand to mouth, finding a crust as best they can. It is from those who have fallen down in their luck that the mastermind behind the financial scam and murders recruits their victims. We meet some great picaresque characters including Maggoty Meg whose legerdemain provides the evidence which leads to the resolution of the case and Cripples, the coffee seller on the Embankment who is minus an arm and a leg, one from either side so that he is perfectly balanced.

Much of the best writing is reserved in developing the character of Percy Lawrence, a complex personality who is traumatised by the brutality of the punishment inflicted upon him in prison and is a depressive, behaving like an automaton and, to a lesser extent, Alice Yates, a young woman who is losing her sight. Both are caught up in the tentacles of the fiendish scheme, but for both, at the finale of the tale, there is the prospect of some form of salvation. There is a humane streak that runs through Punshon’s work, highly unusual for his chosen genre, but one which gives his better works an extra dimension.

The plot also involves the assumption of identities. To pass it off successfully it is important not to confuse your Monads with your Spinoza. Own is intrigued by the philosopher he meets, Beale, even goes back to his old Oxford college to check the man’s credentials – it is always handy to have a don on tap – and begins to realise that there is more to him than meets the eye. The detective, though, has more pressing problems to contend with, not least the realisation that some of his immediate family are perilously close to having their collars felt, an embarrassment that would spell the end of a promising career.

He also battles for his life in a fine set piece as he gets to grip with the culprit. Those favourite accessories of Miss Silver and Mrs Bradley, knitting needles, come to his aid, to ensure that justice prevails.

The scheme may be a little preposterous, as is the idea that drowning in a bath whether the victim has been drugged or not could be passed off as anything other than accidental, but this is a wonderful book, entertaining, gripping and one which wears its heart on its sleeve. This is Punshon at his best.

May 9, 2022

Plant-based Milks

A historical perspective gives a lie to the contention that plant-based milks are just a modern fad, whose fortunes will wane as quickly as they have risen. After all, the milk of a coconut has been drunk ever since man first worked out how to crack its hard shell. Etymologically, milk was used as a term to describe the milk-like juices or saps from plants from the early 13th century. Even more intriguingly, the earliest recipe books in English contain references to the use of plant-based milks.

The Forme of Cury, written in 1390, includes a recipe for blank maunger, probably a dish derived from the Arabs but blander due to the paucity of spices available. Along with rice and capons, sugar, salt, this dish, often given to invalids to strengthen them up, used almond milk as its base. Utilis Coquinario, a cookbook written at the beginning of the 14th century instructs the reader on how to make butter of almond milk. In the earliest German cookbook, dating from around 1350, Das Buch von Guter Spise, almost a quarter of its recipes use almond milk.

Almonds were an expensive commodity, even though they were widely grown in England, three times the price of a pint of butter, putting them ordinarily beyond the reach of all but the wealthy. Butter and milk made from almonds were especially favoured by those who wished to observe the letter, if not the spirit, of the Church’s restrictions on the consumption of meat and dairy products during Lent. As they were plant-based, they could be enjoyed with a clear conscience.

Soya milk, made from the soybean, has an equally long pedigree, initially in China, and is the most widely recognised of the plant-based milks. First mentioned in Chinese texts from around 1350 and in recipes in cookbooks from the 17th century, it was also served hot in tofu shops and drunk for breakfast. The bean was “discovered” by occidentals in the late 19th century, the term “soy-bean milk” first appearing in a report produced by the US Department of Agriculture in 1897, comparing its attributes with those of cow’s milk.

An early advocate of the benefits of soya milk was Li Yuying who established the first manufacturing unit in Colombes in France in 1910 and held British and American patents for production processes. What to call it, though, was a question which mired soya milk producers in contentious litigation with authorities and dairy farmers for decades. The issue was only resolved in the United States in 1974 when the courts ruled that it was a “new and distinct food” rather than ersatz milk, while in Britain in the 1970s it had to be called “liquid food of plant origin” and then “soya plant-milk”.

The 1970s and 80s saw improvements in production techniques, enhancements to taste and consistency, and the development of Tetra Pak packaging extended shelf-life, helping soya milk to establish pre-eminence amongst other plant-based milks. The emergence of strong challengers, though, in the form of oat milk and, the new kid on the block, potato milk, looks set to change that.

Potato milk, available from on-line providers and, since February 2022, in Waitrose stores, is even more sustainable than any other plant-based milk currently available. According to its manufacturer, Swedish-based DUG, winner of the “Best Allergy-Friendly Product” in the 2021 World Food Innovation Awards, potatoes are twice as land efficient as other plant-based options and use 56 times less water than almonds. Dairy-free, and minus gluten, casein, fat, cholesterol, and soy, potatoes are a good source of vitamins D and B12 and the milk, which is very creamy and tastes good in coffee, is fortified with important vitamins and minerals.

All nut, bean, or water-base plant-based milks are made using a similar process. The main ingredient is soaked in water for several hours, before being blended into a puree which is then filtered to separate the milk from the plant matter. The milk is then sterilised by boiling and flavours are added to enhance the taste.

Plant-based milks have long been with us and will continue to offer us an alternative for years to come.

May 8, 2022

Bottle Of The Week

The drinks industry is slowly embracing sustainability and making strides to reduce its carbon footprint. Single-use glass bottles and their transportation make up 39% of the overall wine industry’s carbon emissions.

An Ipswich-based company, Frugalpac, reckon they have come up with the answer – the Frugal Bottle, which is made from 94% recycled paper and has a carbon footprint that is just a sixth of a single-use bottle. To counter concerns that a soggy paper bottle will cause its contents to leak, it has a recyclable plastic pouch inside. Whether the wine will taste the same as when it is poured out of a dark-green glass bottle is a matter for the drinker to decide.

The first vintner to embrace the paper bottle, although trying not to squeeze it too hard, is alt-format specialist, When in Rome. They have a trio of wines, their Peccorino IGP Terre di Chieti and Rosato, produced by a grower in Aruzzo, and their Primitivo IGP Puglia, produced by Tenuta Viglione, available in the new format through Ocado.

Sir Kenelm Digby will doubtless be amused that it has taken nigh on four centuries to come up with an eco-friendly alternative to his revolutionary glass wine bottle. Let’s see whether it catches on.

May 7, 2022

Typo Of The Week (2)

Typographical errors are the bane of the lives of all those associated with the production of books, journals, and newspapers. When Robert Barker and Martin Lucas printed 1,000 copies of their edition of the Bible in 1631, they had failed to spot that they had omitted the word “not” from the seventh commandment in Exodus 20:14.

They had produced what became to be known as the Adulterous or Sinners’ or just plain Wicked Bible. The error which encouraged the commission of adultery was only spotted a year later and while it did not exactly bring the wrath of God on the heads of the unfortunate duo, it did provoke the ire of King Charles I. Barker and Martin were summoned before him, were stripped of their printer’s licence, and were fined £300, which, fortunately for them, was suspended. Most, but not all, of the bibles were destroyed.

One has been discovered in New Zealand, Chris Jones, a medieval historian at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, announced a few days ago. It was unearthed in 2018 and is owned by the Phil and Louise Donnithorne Family Trust. It was in poor condition, with its cover and some end pages missing, and had suffered some water damage. It has just one illegible name in the frontispiece and this version uses red and black ink, unlike many of the other surviving copies. How it got to New Zealand is a mystery as is whether the typo was deliberate, an act of industrial sabotage, or just carelessness.

It has taken four years to restore the Bible, but the text is being digitised so that all, with internet access, can enjoy it, fortunately with the typo still there. It would be a shame to correct it.

May 6, 2022

Twenty-Five Of The Gang

The death penalty, execution by hanging, brought an end to many a criminal’s career. Those for whom such a gruesome ending could be foreseen were told hemp’s grown for you, meaning that their name was already on an executioner’s cord. The rope used to hang convicted felons was made from flax which, in turn, came from hemp.

To avoid a life of crime might be described as hill-top literature, sound advice. When cycling took of in the latter part of the 19th century, it was customary for boards to be positioned at the top of a steep hill warning cyclists of the steepdescent in front of them.James Ware, in his Passing English of a Victorian Era, tells the tale of a cyclist in Ireland (natch) who hurtled down a steep and dangerous hill and was surprised not to see a board with the usual warnings. When he got to the bottom of the hill, he found a sign proclaiming that “This hill is dangerous to cyclists”.

A phrase which I will endeavour to use when the occasion arises is to introduce the cobbler to the tailor, a marvellously vivid and inventive way to kick someone up the backside.

Kodaking is a fascinating example of the use of new technology to develop slang. It derived from what Ware described as the snap=shot photographic camera, named after its inventor, and was used to describe the practice of surreptitiously obtaining information. It was used in a theatre review of Sir Henry Irving’s performance in Richard III; “our eyes are riveted on his face, we are interested in the workings of his mind, we are secretly kodaking every expression, however slight”.

May 5, 2022

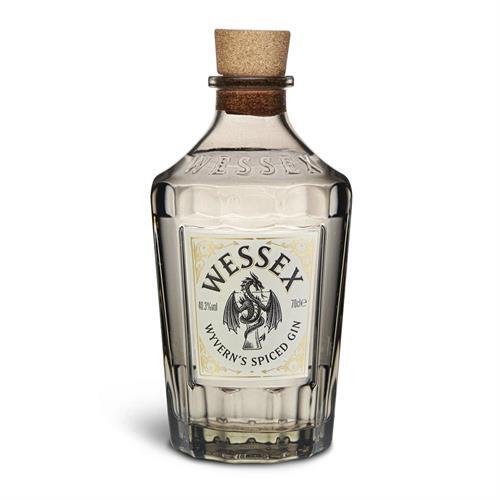

Wessex Wyvern’s Spiced Gin

Even the most intrepid explorer of the ginaissance will find that they have their favourites or hit upon a distillery whose range of gins, like the Sirens in Greek mythology lure, and charm them into their warm embrace, never to let them go. This is the effect that the spirits of Wessex Distillery, found deep in the Surrey Hills in Wormley, near Godalming, in what was eastern Wessex in days of yore, are having on me, establishing them amongst my all-time favourites.

There is a lot to admire about the Distillery. It is firmly a family enterprise, the Clarks having set up shop in 2017, although Jonathan had been involved in the City of London distillery from 2012 in what was a long, protracted, and occasionally bitter, saga to establish the first distillery in the Square Mile of the capital in two hundred years. All their gins are made in a 240-litre copper pot still, named Toby after a grandparent, reinforcing the family feel about the enterprise.

The bottles are distinctive with a no nonsense look of a potion bottle about them; dumpy, thick glassed, fluted, with a wide shoulder embossed with the name Wessex, leading to a short neck and, a welcome feature, a real cork stopper. Their logo features the Wessex Wyvern, a legendary bipedal dragon, noted for the lack of fire that it exhales from its mouth, wrapped around the iconic Wessex Gin goblet. The choice of logo certainly grounds the distillery to its locale but sits a little oddly on the greyish coloured bottle which they use for their Wessex Wyvern’s Spiced Gin.

Jonathan and his team are also proficient marketeers, always willing to tempt neophytes and old hands alike with interesting and innovative offers. Ahead of Valentine’s Day they were promoting a 15% discount and free branded goblets on their range of spirits, an offer that proved too much for me to resist. There are also nice, if unnecessary, features to look out for such as the silver penny that hangs around the neck of some of their bottles, an exact replica of the rare coin from the age of Alfred the Great. Everything about the product and its presentation exudes careful thought, love, pride, and being at one with the traditions of craftsmanship.

Tired of gins that are insipid to the taste, or too sickly and sweet, or have lost contact with the central premise that first and foremost gin is a juniper-based spirit, I like to taste the juniper and for the drink to be distinctive, with a presence and, ideally, a bit of a kick. It is not much to ask for, but, increasingly more difficult to find. What intrigued me about Wessex’s Spiced Gin was that it promised me a “robust, fiery gin”.

Although, frustratingly, there is no definitive list of the botanicals that go into the spirit, it is pretty clear that the foundations of this gin are built on a solid and welcome bedrock of juniper and coriander. The top notes are provided by fresh ginger, cardamom, and cubeb, while a not inconsiderable kick is provided by Indian cloves before the longer lasting citric notes provide a cooling aftertaste. I found it remarkably well-balanced as a drink with all the disparate elements allowed time to play their part and the potency of the spices not allowed to overwhelm the whole. Some care needs to be exercised over choice of mixer to avoid upsetting the delicate balance.

With an ABV of 40.3% its punch is not so much one to the solar plexus as one that lets you it means business. It is a seriously impressive gin from a seriously impressive distillery. Keep an out for it, you might even stumble across an offer.

Until the next time, cheers!

May 4, 2022

Bats In The Belfry

A review of Bats in the Belfry by E C R Lorac

Bats in the Belfry is the thirteenth in the Robert Macdonald series from the pen of Edith Caroline Rivett, the woman behind E C R Lorac, originally published in 1937 and now reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series. For a prolific writer, this was published in the same year as These Names Make Clues and The Missing Rope, the latter under her other pseudonym of Carol Carnac, her standards rarely slip from her impressive norm.

Lorac has a wonderful sense of place and time. Her descriptions are wonderfully atmospheric, bringing the dirty, foggy London of the thirties alive to the reader. She also adds a dash of gothic with the gloomy, sinister, run-down tower of a building, the Belfry studio, known as “The Morgue” with its resident owl and bats. It is here that mysterious and inexplicable events occur, an unexplained assault on Grenville, an abandoned suitcase complete with passport is found, and more gruesome still, a body is found plastered into an alcove, minus head and hands to avoid identification, as in Christopher Bush’s The Case of the Bonfire Body.

Macdonald is Lorac’s go-to police detective and is an amiable guide through the intricacies of the plot and the rigours of the investigation. He has little sense of self-importance, diligently follows the clues wherever they may lead him, checks and tests alibis, and, apart from one leap of intuition, not prone to wild flights of fancy. He has a diligent team of officers to support him, whom he respects and allows to play their part, and operates with no little humour. Macdonald is also acute enough to realise that when all the parts of a case fit together a little too neatly, there is more to it than meets the eye.

This is certainly the case here, as Lorac has constructed a plot that twists and turns with five possible solutions until the final pieces of the jigsaw fall into place. The tension rises towards the end with a car chase. This is not the adrenaline-fuelled high-speed drama of modern crime dramas, but a drive across London in a police car with a fire engine which, ignominy of ignominies, overtakes them and whose crew save the day. And the culprit will be a surprise to many a reader, so beautifully does Lorac handle the intricacies of the plot, dropping a clue here and there, but managing to maintain enough of a mystery to make the revelation dramatic. It is impressive stuff and the quality of Lorac’s prose makes it not only a page-turner but also a joy to read.

The story begins with the aftermath of the funeral of Bruce Attleton’s distant Australian cousin, not just a device to introduce all the principal characters – even the mysterious Debrette makes an ex deus machina-like appearance by way of a telephone call that visibly distresses Bruce – but also to introduce the central theme of inheritance and the sudden deaths of those in line for the Old Soldier’s carefully curated inheritance. The conversation turns, as it does, to how to dispose of a body, one presciently suggesting plastering it up in the fabric of the building. The acute reader will observe who offers solutions and what they entail.

Both Debrette and Bruce disappear, there is a convoluted trail of possible beneficiaries across two lines of the family, one French, marital infidelities, thwarted matrimonial ambitions, possible blackmail, and an incredibly accident-prone Robert Grenville manages to get himself hit over the head not once but twice, and run over by a motor cycle to boot. It is great fun as Macdonald wrestles with the thorny problem with all the suspects having motive enough to arouse his suspicions.

I found it an intriguing and engaging mystery, beautifully written with vibrant characters. Lorac rarely lets you down.