Martin Fone's Blog, page 121

June 1, 2022

Inginious Gin

As someone unable to spot a trend until its rear lights are disappearing over the horizon, I have been a latecomer to the world of NoLo, no alcohol or low alcohol drinks. I have always studiously swerved the dubious honour of being a designated driver, not fancying an evening gazing on a soft drink with faintly disguised hostility and have never felt the need to improve the wellbeing of the temple that is my body by eschewing alcohol, it is something has passed me by. In an era when more people are becoming health conscious and the boozy lunch is frowned upon by employers, there is a nettle for NoLo producers to grasp.

And grasp it they are. With 58% of people drinking more NoLo in late 2021 than a year before, and eight out of ten looking to embrace more options, according to Nielsen CGA, the market is ready. Inginious Gin is aimed at those looking for a refreshing gin and tonic without the alcoholic content. The brainchild of Simon Liddle and developed with the assistance of Sloemotion Distillery in North Yorkshire, it is a concentrated 43% ABV gin spirit with ten times the flavour concentration of a full-strength alcoholic gin.

Twelve “responsibly sourced” botanicals are used in the manufacture of Inginious, including the classics of juniper and coriander and a heady hit of citrus flavours including lemongrass, grapefruit, and lime. There are two principal ways in which NoLo gin is made. The first is to soak the botanicals in purified water rather than a neutral spirit until the liquid takes on a flavour of a gin without the alcoholic kick. The other is to use a small amount of neutral flavoured spirit into which the selected botanicals are added. The liquid is then gently heated over several rounds of distillation to extract the flavours of the non-alcoholic ingredients. The vapours rise, condense, and are cooled, diluted, and separated to produce the drink.

It is a lengthy process – often lengthier than making alcoholic gin – involved, and complex. However, Inginious does seem to have cracked it, producing what to the taste is like a London Dry Gin. With juniper to the fore mixed with earthy spices and peppers and a pronounced citric element provided by lemongrass, grapefruit, and lime, it makes for a well-balanced, refreshing drink which does not compromise taste while reducing the alcohol content to just 0.2 units per serve. Inginious, you might say.

The bottle is stylish with an art deco feel about it, circular, stubby, with wide shoulders and a short neck leading to a wooden top and an artificial stopper. The labelling is geometric in design, making good use of blues and turquoise, with gold edging. The strap line is “big taste in small measures” and they are not kidding.

The biggest shock for a NoLo neophyte like myself is that the bottle only contains 20cl of the concentrate. The reason is that it is a concentrate, and you only need 5ml to make the equivalent of a double. A bottle for those with a steady hand should produce forty servings. To ensure that you pour just the right amount, each bottle comes with a long measuring ladle.

I did find it difficult to pour the right amount of concentrate without spilling some and wonder whether a pipette inside the bottle might make for a more efficient way of delivering the spirit. That said, I found it an enjoyable drink and it might even persuade me to put my hand up when a driver is called for. Now that would be something.

Until the next time, cheers!

The Key

A review of The Key by Patricia Wentworth

This, the eighth in Wentworth’s Miss Silver series, originally published in 1944, is straight out of her playbook. There is a murder, an international conspiracy, and a bit of love interest, all told with her usual verve and pacy narrative. There being a war on, the international gang is made up of German collaborators one of whose members, somewhat surprisingly at first blush, has merged into the fabric of a quiet English town. The lure is to keep tabs on a German émigré, Michael Harsch, who is working away on developing a form of powerful explosive which could change the fortunes of the war.

When we first meet Harsch he has just finished his final experiment, has rung up Sir George Rendel of the War Office to make an appointment to hand his results over, and walks into the Ram for a drink. As he enters the premises, he has a shock and sees a figure from his past. He departs rapidly. It is a sliding doors moment. If he had taken a different path, there would have been a different outcome. Instead, he makes his way to the local church where he plays the organ and is found dead. The inquest gives a verdict of suicide, but not everyone is convinced. Sir George Rendel sends the dashing Major Garth Albany down to carry out his own investigations.

It soon becomes apparent that Harsch has been murdered in what is a variation of a locked room mystery. The door of the church was locked. There were only four keys to the church and the obvious inference is that one of the holders was the murderer. Our old friends, Lamb and Abbott, lead the investigation on behalf of the Yard and they have Harsch’s housemate, the rude and abrasive Evan Madoc firmly in their sights. Madoc is a keyholder, a pacifist, and, under the terms of Harsch’s will, would inherit his scientific papers. He had the power to kill the project stone dead.

Miss Silver is called in by Janice Meade, Madoc’s secretary, who also provides the love interest with the Major. Quietly, Miss Silver carries out her investigations and soon discovers that Lamb has got the wrong end of the stick and that there is more to the mystery than meets the eye. Her inoffensive, discreet method of investigation enables her to extract information from witnesses who would never have been so forthcoming to the police. She discovers a mischievous young boy who has some vital information about the comings and goings of the some of the key suspects including Madoc and the strange companion, Medora Brown. She soon unravels her relationship with one of the protagonists.

Then there is the village drunkard, Ezra, who bewails the fact that the beer is now so weak that it takes much longer and is more expensive to achieve the desired effect. He boasts that he has some vital information that will be worth a lot of money to him. Before he can cash in on his good fortune, he too is murdered, found drowned in a shallow patch of water, the worse for wear, having consumed some brandy, not his normal tipple, over and above his usual quantity of beer.

Alibis may seem cast iron but one of the key premises of this story is familiarity breeds contempt. People, so used to hearing things, can make mistakes or jump to conclusions. The murderer took advantage of this trait in human nature to evil effect and nearly got away with it. The denouement is not a result of deduction but a series of happenstance involving a negligently discarded seed catalogue, a shared telephone line, a nosy invalided woman, and an oh so handy neighbour. There are the usual red herrings and whilst I had my suspicions as to the identity of culprit, I was not certain until the dramatic ending.

Formulaic Wentworth’s tales may be, but she is a consummate storyteller and writes with verve and pace, and no little humour. The story shone light on the assimilation of German emigres into British society and revealed that they were viewed not without suspicion. The developing admiration of Abbott for Maudie was also a bonus of this engaging tale.

May 31, 2022

The Case Of The Purple Calf

A review of The Case of the Purple Calf by Brian Flynn

Even the most ardent fan of Brian Flynn would be hard pressed to make a convincing case that this, the sixteenth in his Anthony Bathurst series, originally published in 1934 and now reissued by Dean Street Press, is one of his finest. For such a normally innovative writer it struck me as a tad pedestrian and, stylistically, the language is rather overblown at places and phrases like “it will be remembered that…” suggest that Flynn may have some form of serialisation in mind. It is a shame because the idea behind it was full of possibilities.

It is not often that you come across a story that involves a traveling fair, a dodgy London nightclub called the Purple Calf where you can have kippers and a bottle of wine which must have given it a certain atmosphere, an alligator trainer, an ingenious and somewhat gruesome murder weapon, and a series of motor accidents. The fair provides Flynn with the canvas to develop a series of picaresque characters, including the obligatory dwarf who has a bigger role to play in the mystery than initially meets the eye.

What starts Bathurst off on his trail to solving the shenanigans centring on the Purple Calf is a series of three seemingly unconnected motor accidents, in each of which a young woman is found dead near the vehicle with horrific injuries. Sir Austin Kemble, Commissioner of Police, thinks they are just tragic accidents, but Bathurst, as his wont, thinks that not only are they suspicious but also that they are linked in some way. Determined to prove Kemble wrong, he sets out to untangle the mystery.

There are a couple of promising leads. The motor accidents take place near the encampment of the travelling fair. Coincidence or a common theme? On the bodies of the three female victims are found coins, but they are only coppers. What was the significance of this? The circumstances of the death of a fourth victim seem at odds with the identified pattern surrounding the other victims. Does this mean that Bathurst has been barking up the wrong tree with his carefully formulated theories?

The old legal principle “exceptio probat regulam” convinces Bathurst that the unfortunate Rosa is an outlier and that her death has nothing to do with the matter in hand. In fact, it rather reinforces his theories. Emboldened, with help from some companions he has picked up along the way and with the sterling assistance of his old policing friends, MacMorran and Norris, he undertakes an audacious raid on the fair. Not only does Bathurst save Margaret Fletcher from a gruesome death, but he solves the mystery of how the victims suffered their gruesome injuries. The American title for the book, as often is the way, The Ladder of Death, rather gives the game away.

There is too much going on off stage in this story for my liking, especially in the resolution of what was really going on at the Purple Calf and how it related to the fair. I had worked out that L’Estrange and Lafferty, the eminence grise of the fair and his sidekick, and the two Brailsfords, seemingly friendly individuals who had imposed their presence on Bathurst, had some connection – Flynn pays homage to Conan Doyle’s The Man with the Twisted Lip here – but money counterfeiting and inheritance protection were beyond my ken.

The fair allowed for an ingenious murder method, but it all seemed an extraordinary amount of effort to achieve something that could have been done more easily. Then again, Bathurst would not have had the opportunity to show his genius and we would not have had an entertaining enough story, even though it does not hit the heights Flynn can achieve.

May 30, 2022

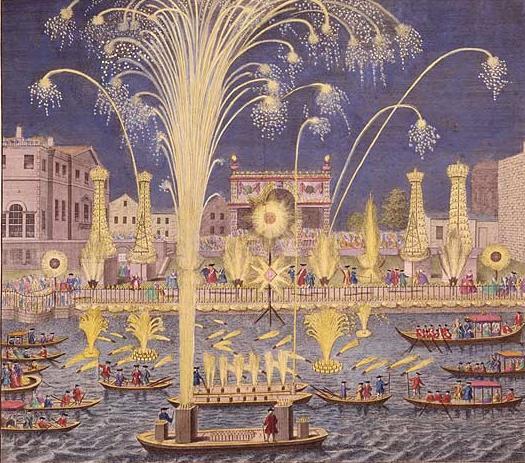

Royal Jubilees

Royal jubilees were much more infrequent than religious jubilees, depending upon the longevity of the monarch and originally marked fifty years on the throne. The first English monarch to reach that landmark was Henry III, but whether he was inclined to celebrate, as in 1266 he was in the middle of fighting a civil war, is doubtful. There are no records to show how Edward III or James VI of Scotland and James I of England celebrated their fifty years on the English and Scottish thrones respectively.

The jubilee of George III was celebrated, though. Curiously, the date chosen for the celebrations, October 25, 1809, was the forty ninth anniversary of his reign, although, technically, the start of his fiftieth year. George’s ability to participate was limited by poor health and failing eyesight but the occasion was marked by a service at Windsor and a fete at Frogmore, which, according to John Stockdale’s The New Annual Register, “in point of taste, splendour, and brilliancy has on no occasion been excelled”.

At 9,30 in the evening the gates were thrown open to the nobility and gentry who had tickets of admission and the Royal family stayed until the early hours, enjoying the sight of Britannia being transported in a chariot drawn by seahorses and an impressive display of fireworks. In London, meanwhile, the Lord Mayor led a procession to St Paul’s Cathedral for a service of Thanksgiving, before finishing the day off with a dinner at the Mansion House.

Celebrations were held throughout the land. Roast ox and sheep, and plum puddings were eaten, strong ale quaffed, sermons preached, bells rang out, flags waved, God Save the King sung, and food and alms distributed to the poor. In Abingdon cakes were thrown from the top of the Market House, while in Blisworth in Northamptonshire, the “respectable” inhabitants gathered at the Grafton Arms for a supper where “harmony and convivial mirth crowned the festivities of the day”. Debts were cancelled and prisoners released, including “all persons confined for military offences” and in Reading some Danish prisoners of war.

One Oxfordshire village reportedly insisted that any child born there during the jubilee year be called Jubilee George or Jubilee Charlotte. For those looking for more conventional souvenirs of the event, there were souvenir medals bearing the portraits of George and his queen, Charlotte, and commemorative plaques, jugs, mugs, and bowls to buy. By the time Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee on June 21, 1887, the range of souvenirs had been extended to include commemorative coins and stamps and a range of bric-a-brac such as teapots, butter dishes, mirrors, handkerchiefs, woven silk pictures, wallpaper, and pipes.

One of the highlights of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, on June 22, 1897, was her stately procession through the streets of the West End, City, and some of the poorer quarters of London, accompanied by many of the crowned heads of Europe and princes, maharajahs, and chiefs from around the world. Cutting edge technology allowed the Queen to send a telegraphic message to all quarters of the globe; “From my heart I thank my beloved people. May God bless them!”

There were two royal jubilees in the twentieth century, both marking the monarch’s twenty-fifth anniversary on the throne, and there have already been three in the 21st century, testament to the longevity of Queen Elizabeth.

Her Platinum Jubilee celebrations are unlikely to match the Heath Robinsonish way in which her grandfather, George V, lit the bonfires to mark his Silver Jubilee on May 6, 1935. At 9.55pm he pressed a button in his study, activating a relay circuit connected to a telephone box in Hyde Park, which blew a fuse inserted in a nearby bonfire, thus setting off the chain of fires.

Boniface VIII introduced jubilee years to the west in response to a period of pandemic, poverty, and war in Europe. There is a curious aptness that 2022 should be a jubilee year too.

May 29, 2022

Find Of The Week (4)

One of the only reasons to go into a charity shop, apart from supporting a good cause, is in anticipation of finding an item that is being retailed for far less than its monetary value. It requires, of course, that the volunteers fail to spot the import of what they have had donated, unlike Paul Wyman who helps at the Oxfam branch in Brentwood.

As he was sorting through a box of items donated by an unknown donor in October 2020, he came across an unusual bank note. Paul was savvy enough to realise that it could be rare and contacted an auction house. It turned out to be a Palestinian £100 note, issued in 1927 and given to high-ranking officials during the time of the British Mandate there. Fewer than ten are known to exist and a reserve of £30,000 was put on it.

When it went under the hammer on April 28th this year at Spink and Son’s auction house in Bloomsbury it sold for £140,000 netting the charity a tidy profit.

Spare a thought for the unfortunate donor. The moral of the story is always check what you give or throw away.

May 28, 2022

Smile Of The Week

I never find shopping a pleasurable experience. It never fails to astonish me when the person behind whom I have been (im)patiently queuing is astonished to find, after painstakingly loading their goods into bags, that they are required to pay for them. This results in them fumbling around in pockets and bags until they find their wallet or purse and finally complete the transaction.

New technology in the form of a Biometric Checkout Programme, trialled in Brazil and soon to be introduced into the UK by Mastercard, may soon change all this. Christened “Payface” it works, inevitably, through a mobile phone app into which users enter their information, including fingerprints and a facial image, which is then paired with their debit or credit machine.

Mastercard claim that you will just need to smile or wave at a camera at the checkout to pay for the goods. Three-quarters of shoppers, according to research, are “positive” about using biometric technology, a market that is estimated to be worth £15 billion by 2026. In some ways, it is the reverse of a shoplifting experience where you have your fingerprints and mugshot taken after you have taken the goods.

Having never knowingly smiled in a shop, it looks as though I am going to have to change my ways.

May 27, 2022

Twenty-Eight Of The Gang

Our language has lost some marvellous words along the way. Mawwormy was an adjective used to describe someone being picky or the act of fault finding. It owed its origin to a character in Isaac Bickerstaffe’s play of 1769, The Hypocrite. Perhaps being mawwormy is to call a dog that is reluctant to fight a meater, one that only bites into meat.

Advertising has long made its mark in popular speech. A mustard plaster referred to a dismal, doleful, pallid young man and was often used in the form of “put a mustard plaster on his chest”, an attempt to liven him up. The origin of this phrase came from a song written by celebrated music hall and pantomime writer, E L Blanchard, in association with and to promote Colman Mustard. Perhaps the youth referred to knew that his elm is grown, a premonition of imminent death. Elm wood was the most common material coffins were made from.

A Norfolk Howard was a euphemism for a frequent nighttime companion, the bed bug. It owed its origin, James Ware records in his Passing English of a Victorian Era, to a chap called Buggey who advertised in the newspapers his change of name to Norfolk Howard. As well as producing a bit of slang to describe a bed bug, Buggey’s actions provoked a wave of sympathy in the newspapers of the time for people who were saddled with objectionable or vexatious surnames.

The Times even went so far as to print a list of over a hundred surnames that it considered to be vexatious. These included Asse, Belly, Cheese, Dunce, Drinkmilke, Flashman, Bungler, Fatt, Clodde, Demon, Fiend, Funck, Hagg, Holdwater, Juggs, Idle, Kneebone, Lazy, Leakey, Milksop, Honeybum, Pisse, Pricksmall, Pighead, Poopy, Quicklove, Rottengoose, Sprat, Squibb, Shittel, Swine, Silly, Spattle, Teate, Vile, and Whale. How many possessed these surnames and how many followed Buggey’s example is not recorded.

May 26, 2022

Inverroche Verdant Gin

Based in the Western Cape in Stilbaai, Inverroche distillery is the brainchild of Lorna Scott, its name paying homage to her Scottish ancestry – inver meaning a confluence of water – and to the landscape of the area where it is based – roche being French for rock. Situated in the Cape Floral Kingdom, home to more than 9,000 species of plants or fynbos found nowhere else in the world, it is no surprise that Inverroche Verdant Gin takes advantage of this natural bounty. Scott whittled down the number of contenders to a mere 300 plants, enough to be going on with, and the fynbos that go to make up this spirit have all been hand-selected from the mountainous and rocky regions.

Sustainability and being at one with nature are key drivers for this enterprise and in what is a nice touch, their Mother’s Day presentation gift set came with a “for ever” bottle bag and a box containing six balls made from clay, peat-free compost, and chilli powder, the latter to ward off slugs and snails, chock full of wildflower seeds designed to bring a riot of colour, aromas, and pollinators to the garden. I have already sown mine – you just throw them on to a bare patch of soil and nature should take care of the rest – and look forward to seeing the results.

The bottle itself is elegance personified, tactile and easy to hold, shaped like a lightly angled trapezoid with broad shoulders a short neck, and a cork stopper. The labelling is stunningly classy and minimalist, using gold and black lettering on the sort of paper that Conqueror stationery is made from. The label at the rear of the bottle is more informative, informing me that the “rare and enigmatic” botanicals of the region ensure a “uniquely South African gin”.

Each bottle is labelled and numbered by hand – mine came from Lot L549 and was number 0149 and is “crafted with nature”. Fittingly, given its name the gin has a distinctive golden-green hue. The drinker is promised that “delicate floral aromas reminiscent of elderflower and chamomile, lead to summer blooms, a touch of spice, subtle juniper, zesty lemon, and alluring liquorice”.

In the glass the spirit delivers a heady mix of fresh, vibrant floral notes with juniper and hints of limoncello playing gently in the background. No shrinking violet with an ABV of 43%, this elegant, smooth drink is a must for lovers of floral gin. It is a hugely impressive gin and I can understand why many people lucky enough to have sampled it are raving about it. Floral gins are not normally my thing but it is very refreshing, ideal for a summer’s evening as the sun is setting in the distance.

Until the next time, cheers!

May 25, 2022

Seven Clues In Search Of A Crime

A review of Seven Clues in search of a Crime by Bruce Graeme

It is always a pleasure to find a new author and Bruce Graeme, a nom de plume of Graham Montague Jeffries, is a new one on me. This is the first in his series featuring the bookshop owning amateur sleuth, Theodore Ichobad Terhume, known as Tommy to his mates, and was originally published in 1941 and now reissued by Moonstone Press.

It is even more of a pleasure when you come across an author who writes with wit, verve, and no little panache and is willing to turn on its head the hackneyed genre of crime fiction. This is no straightforward crime novel – murder, investigation, culprit unmasked – nor even an inverted murder mystery where you know whodunit and the story is more about how the sleuth catches them, but something even more radical.

Terhune, an ingenu in the field when it comes to the world of detection, although, naturally, he has read all the murder novels, is drawn inexorably into a rabbit hole by a collection of odd incidents and clues (seven in total) which bit by bit lead him to unearthing a crime and, ultimately, a murder. The identities of the victim, certainly, and the culprit, to a lesser extent, are almost throwaways at the end of the story. What interests Graeme is the process of investigation, of picking the bones from a series of seemingly random clues and chance events into something comprehensible. Like Terhune, the reader is drawn into Graeme’s intriguingly convoluted plot, the deeper we go the less able we are to resist the lure of finding out what it is all about. It is tremendous fun.

Terhune’s adventure starts one foggy evening as he rides home from his bookshop in Bray-in-the-Marsh and foils an attack on Helena Armstrong by five men who were hunting for something in her handbag. Helena, who inevitably falls for the bookish Theodore, is the companion to Lady Kylstone, an American widow. Terhune discovers that the thieves are after the key to the Kylstone family vault, which they steal and then raid the vault leaving behind a gold fountain pen with a strange insignia. The sleepy town of Bray, where little happens, is all agog at the developments and Terhune’s unexpected acumen as a sleuth. He learns from Alicia MacMunn that her dead father’s manuscript on the genealogy of the principal families in the area has been attacked with the pages from A to D removed. What does this mean?

The mystery deepens as Terhune discovers a telegram from New York, a piece of paper with the name of Blondie and an address on it, a statue of Mercury, and the curious life of Margaret Ramsay, one time secretary to the MacMunns. Terhune travels to New York, not before an attempt is made on his life on board the liner, allowing Graeme to have fun with an Englishman in the Big Apple, and gains further insights into the mystery.

Ultimately, it is a tale of inheritance, an unacknowledged marriage, and hidden identities which Terhune brings to a point where he can call upon his police mentor, Inspector Sampson, to wrap it all up. It is great fun, laced with humour and some sharp observations of life in a quiet English backwater and a mystery which is well nigh impossible for the reader to solve until the bitter end.

Terrific stuff.

May 24, 2022

Shadows Before

A review of Shadows Before by Dorothy Bowers

This is the second of Dorothy Bowers’ Inspector Pardoe mystery murders, originally published in 1939 and now reissued by Moonstone Press. I found it less accessible than her debut novel, Postscript to Poison, and it has quite a complicated plot. Structurally, it was reminiscent of a Christopher Bush novel with the reader fed a series of seemingly unrelated sequences – it opens with a series of letters and then a second section in which we follow Aurelia Brett as she is interviewed and offered the role of companion to Catherine Weir – which only make sense and complete the picture as the book reaches its denouement.

And what a finale it is. Through all the highways and byways of the plot Bowers manages to turn the story on its head and come up with a solution many of her readers would not have seen coming. It rescues what otherwise would have been a rather pedestrian novel.

It is another tale of poisoning, Catherine Weir the initial victim. She is suffering from what would nowadays be diagnosed as dementia, needs supervision and is taken to rambling around the countryside collecting plants which she makes into a herbal tea concoction. One night someone slips some arsenic into it and its goodnight, Catherine. Who the culprit was is the task of Inspector Pardoe, Bower’s worthy police detective to discover, and he soon realises that there are a number of suspects who, for various reasons, may have been sufficiently motivated to do away with the old woman.

The Weirs had only moved into Spanwater, a country house set in a remote corner of the Cotswolds favoured by Romanies and Oxford dons, two years previously, having had to leave their previous residence under somewhat of a cloud after Matthew Weir, a professor, had been acquitted, somewhat to the surprise of many, of the charge of poisoning his sister-in-law. That his wife should now have been poisoned is surely more than an unfortunate coincidence.

Inheritance, inevitably, features highly as a motive. Catherine is wealthy but her wealth is subject to a tontine-like will, always an open invitation to murder, and how much Matthew will inherit, who is strapped for cash with the prospect of funding the studies of his nephew and niece looming large, is dependent upon whether a young relative, who disappeared to Australia with a dance troupe several years ago, is still alive.

Nick Terris, the nephew, is an enthusiastic supporter of euthanasia, perhaps putting his aunt out of her misery was a supreme act of kindness, and Matthew’s brother, Augustus, is strapped for the cash needed to keep his literary magazine afloat. Outside of the family, there are some odd servants, not least Mord, the butler-cum-manservant, and the religious fanatic, Ms Kingdom, who particularly has it in for a neighbour, Alice Gretton. Gretton has mysteriously disappeared, and Mrs Kingdom helpfully reports that every time Catherine visited Gretton, her health deteriorated.

Inspector Pardoe, Bowers’ sleuth, ably assisted by Sergeant Salt, the perfect foil to the more prosaic theories of his boss, set out to solve the mystery. Amidst yet another poisoning and an accident when the sterring mechanism of a car is tampered with, it becomes clear that Alice Gretton holds the key to the whole thing. What has happened to her and who was she? The answers to these questions produce an astonishing result.

Once I had got into the book, I found it entertaining enough and it was well written and well-paced. There was enough in it to persuade to continue following the adventures of Pardoe.