Martin Fone's Blog, page 101

December 21, 2022

Swan Song

A review of Swan Song by Edmund Crispin

Many moons ago I used to share a flat with someone whose antidote to a hangover was to play Wagner at full volume. As we hit the electric sauce rather often back then, the strains of the controversial German composer could often be heard floating across the backwaters of Camberwell. Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is the backdrop to the very enjoyable that is Edmund Crispin’s fourth outing for his amateur sleuth, Oxford don Gervase Fen. Originally published in 1947 and also going by the alternative title of Dead and Dumb, it was a bold move by Crispin to feature a composer so heavily associated with the Nazis, an attempt to rehabilitate him perhaps or an appropriate backdrop of evil and malice, who knows?

We are familiar with the operatic diva, but Crispin introduces us to an operatic divus, one of the leads, Edward Shorthouse, who is full of himself, obnoxious, and universally hated. He has a number of run-ins with the inexperienced conductor as the opera company prepare to put on Die Meistersinger in Oxford and several of the cast only express a desire for his removal. Even his brother, the eccentric composer, Charles Shorthouse, would love to see him dead, if only so that he can get his hands on his money to finance his ambitious operatic project, The Oresteia.

It is no surprise then that one evening he is found in the Playhouse hanging from a noose. It looks like suicide but on closer inspection there are tie marks on his hands and lower legs and when a post mortem is carried out it seems he has been poisoned as well. The police are happy to accept it as suicide but a rebellious jury at the inquest pass a verdict of murder and Gervase Fen, who already suspects foul play, is determined to work out whodunit and how. Soon afterwards, a junior member of the cast who was only married two days earlier is found on the Playhouse roof having been poisoned and during a performance of the opera, there is an attempt on another’s life.

The plot is such a good take on the usual murder mystery that I will not spoil it. Suffice it to say that there are two murder plots that go disastrously wrong when an innocent inadvertently triggers them off and justice of a sort is kind of done. All I can do if you are intrigued by these gnomic utterances, is to grab a copy of the book and read for yourself.

There is also much more to admire in this book. Crispin writes with great humour and Swan Song is as much a satire of life in operatic companies and academia as it is a murder mystery. He is not averse to a bit of name-dropping, C.S Lewis is spotted on a couple of occasions – it is a Tuesday, after all – and whimsically places Fen amongst detective fiction’s greats when Adam’s wife, Elizabeth, née Harding, plans to interview him for her series on famous sleuths. The descriptions of Fen’s driving style and his noisy, temperamental sports car, Lily Christine, are marvellous. He also has the dialogue of supposedly academic groups down to a tee.

Although amusing, well-written with a flowing pace, Crispin does not give his reader an easy ride. He is not shy in raiding the darkest recesses of the lexicon to test the depths of their vocabulary. The compensations, though, are immense; a clever “impossible” murder which is reconstructed convincingly by Fen, and in part a romantic comedy, with the awkward love affair between Elizabeth and Adam. She is besotted, he does not realise it and it takes the intervention of a third party to make him see sense.

This book has it all.

December 20, 2022

Cold Evil

A review of Cold Evil by Brian Flynn

What I like about Brian Flynn, a sadly neglected writer from the Golden Age of detective fiction and now enjoying a renaissance thanks to the sterling efforts of Steve Barge and Dean Street Press, is his willingness to experiment, to change style, mix things up. He shows a deep appreciation and understanding of the early masters of his craft, especially Conan Doyle, and some of his books veer into the territory previously occupied by the much-derided penny dreadfuls. It might well be that this unpredictability cost him readers, especially if an experiment fails to reach the previously high standards he had set.

I am not quite sure what to make of Flynn’s Cold Fear, the 21st in his long-running series featuring the amateur sleuth, Anthony Bathurst, ALB to his friends and family, originally published in 1938. At its kernel there is a cracking story, but the reader has to work hard to find it. It is a very atmospheric book, mist swirls across the moors and heavy frost makes it crunchy underfoot during late December and early January. The Gothic feel to the tale is set in the first chapter when six worthies gather at the vicarage of St Crayle and swap ghost stories. Martin Burke’s tale of a murderous Indian chimera chills his auditors to the bone and raises the concept of the projection of evil as a murder weapon rather than a gun, knife, or poison.

As if to prove the point, one of the party, Chinnery, disappears on the moor as he walks home. His body is found a week later, with a look of terror on his face, but his body is unmarked save for a red mark behind his ear. It is thought that Chinnery had lost his way and froze to death but Bathurst, who had by now been called in to assist in the search for Chinnery, is not so sure and suspects foul play. Then another member of the party is also found in a semi-frozen state with the same red mark behind his ear, but he survives. A third victim, a woman who was not at the party but is a Justice of the Peace is not so lucky, found on the moor, frozen with the tell-tale mark.

The story is narrated by Bathurst’s cousin, Jack Clyst, and this is one of the book’s weak points. As Bathurst proceeds with his investigations, he disappears, leaving Clyst in the dark. He can only speculate what is going on and follow the clandestine instructions that his cousin sends to him from time to time. This means that the results of Bathurst’s investigations, the identity of the culprit, what really happened to the victims, and what the motivation is are presented to the reader as a fait accompli with no attempt on Flynn’s part to give the reader the opportunity to work matters out for themselves.

Bathurst, a master of disguise, lures the culprit into making a mistake, albeit almost at the cost of the sleuth’s life, and all is revealed. For experienced readers of the genre there are obvious inferences as to who the culprit is but the motivation is produced like a rabbit out of a hat.

The other disappointing features of the book are its pacing, there are long periods where the protagonists sit around waiting for things to happen, allowing them to discourse on and develop theories about the ability to spread evil through the power of thought and mass suggestion – perhaps an oblique reference to the worsening political situation in Europe – and the dialogue between ALB and Clyst, where both spar with each other and seem to have digested a compendium of literary quotations for breakfast.

For those anticipating an extravagant Christmas this year, the book is a salutary read as it features one of the gloomiest and unfestive Christmases in literature. But for the arrival of some carol singers you would not know it was any other day.

My feelings for this book are rather like receiving a perfectly cooked steak only to find the vegetables are soggy and cold. One very much for the aficionado.

December 19, 2022

A Helping Of Brussels Sprouts

They are the Marmite of the vegetable world, their presence on the Christmas dinner table likely to provoke joy or outright disgust. Containing more vitamin C than an orange and with just eighty calories in a half pound, Britons eat more of them than any other European country, around 40,000 tonnes a year, and consume two-thirds outside of the festive season.

Brassica oleracea, variety gemmifera, the Brussels sprout, is a member of the mustard family, Brassicaceae, and a cultivar of the wild cabbage indigenous in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. Unlike the cabbage, which grows directly from the ground, the edible part of the Brussels sprout plant, the cabbage-like buds about an inch or two in size, form in leaf axils along its tall stem.

They may have been first cultivated by the Romans, but more certainly were grown in Flanders and northern France from the 12th century. Mentioned in some market regulations for the Brussels area in 1213, their association with the area earned the vegetable its distinctive name. The first written description of them was provided by Dutch botanist, Rembertus Dodonaeus, in 1587.

By the 17th century sprouts had arrived in Britain, one writer describing in 1623 a cabbage plant “bearing some fifty heads the size of an egg”. Dorothy Hartley in Food in England (1954) cites a gardening manual from 1699 which provides instructions on cooking a vegetable very much like a Brussels sprout, for which, rather than Flanders, “the best seed of this plant comes from Denmark and Russia”.

Hannah Glasse also told her readers how to cook them in her The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747). “Cabbage and all Sorts of young Sprouts must be boiled in a great deal of Water. When the Stalks are tender, or fall to the bottom, they are enough; then take them off before they lose their Colour…Young sprouts you send to the Table just as they are”.

These references pre-date what the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites as the first published reference to the Brussels sprout in English. In his A Plain and Easy Introduction to the Knowledge and Practice of Gardening (1796), the then vicar of the Blixworth in Northamptonshire, Charles Marshall, wrote that “Brussels sprouts are winter greens growing much like borrcole”, kale, perhaps indicating that the plants were valued more for the tuft of leaves than their sprouts.

The first recipe directly referring to Brussels sprouts appeared in Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery for Private Families (1845). She was certainly cooking the buds, which she described as “at their fullest growth scarcely exceed a large walnut in size”. They were to be boiled for eight to ten minutes in salted water and served “upon a rather thick round of toasted bread buttered on both sides…This is the Belgian mode of dressing this excellent vegetable”. The French, she observed, served them with sauce or tossed them in a stewpan with spice of butter, pepper, salt, and veal gravy.

Sprouts were still much of a novelty well into the 19th century. However, their appearance in late autumn made them an ideal fresh vegetable for the table just as the idea of having a large feast to celebrate Christmas Day was taking root in Victorian sensibilities. They were a match made in heaven, at least for some.

Next time we will find out why some people do not like Brussels sprouts. It might be in the genes.

December 18, 2022

TV Critic Of The Week (2)

In the week that the final (for now) three episodes of Harry and Meghan were released on Netflix, a pub in Chiswick, the Duke of Sussex, has issued a suitably succinct and witty critique, renaming their session beer “Harry’s Bitter”. Described as “a royally good tipple” it has an an ABV of just 3.9%.

Entertaining, refreshing, but leaving no lasting damage. Says it all.

December 17, 2022

Birthday Of The Week

It is rare to hear of a government that does something that brings immediate benefit to its citizens but at the stroke of a legislative pen the South Koreans will soon become a year younger. Hitherto, a child has been deemed to be a tear old as soon as it is born and then a year is added to its age every January 1st. Under the system a child born on New Year’s Eve would become two a day later.

However, when it came to determining the legal age for drinking alcohol and smoking and for eligibility for national service, a person’s age was set a nought on birth and a year added each January 1st. It has all got very confusing.

In an attempt to cut the Gordian Knot the Korean Parliament has approved legislation that will adopt the international age-counting system where age is set at nought on birth and incremented by one at each birth day.

The changes will come into force next June. According to a poll conducted by the Ministry of Government Legislation, mare than 80% of South Koreans supported the move and 86% said they would go by their birth date age in their daily lives.

December 16, 2022

The Murder At The Vicarage

A review of The Murder at the Vicarage by Agatha Christie

The Murder at the Vicarage, published in 1930, is the novel in which Agatha Christie introduced Miss Jane Marple to the crime fiction world, establishing as a rival in their affections to Hercule Poirot who had made his debut ten years earlier, in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Both are eccentric, but in her initial portrayal of her female sleuth Marple comes across as a nosey parker and someone who is not universally liked. The vicar’s wife calls her “the worst cat in the village”.

The story is set in Marple’s home village of St Mary Mead. It is a sleepy village where nothing much happens and what does is voraciously picked over by its resident old spinsters. Miss Marple has a knack of being at the right place at the right time, overhearing important snippets of conversation and with her fertile mind and her insights into the psychology of human behaviour is able not only to compile an encyclopaedic knowledge of what is going on but also to interpret its true meaning.

It is these skills which enable her to resolve a mystery that rocks the village, the murder of Colonel Lucius Protheroe who is found shot in the vicar’s study. Beside him is a note timed at 6.20 and the clock has been overturned and has stopped at 6.22. As is the way with these stories, the murder victim is unpopular and there is no end of villagers who either have expressed their wish that he was dead or had reason to kill him.

Almost immediately the village’s artist, Leonard Redding, hands himself in, claiming that he was the murderer. Then the Colonel’s wife, Anne Protheroe, confesses. Neither confession seems to hold water, as Redding’s recollection of the time he committed the murder is incorrect and Miss Marple reveals that Anne Protheroe did not have a gun when she saw her enter the vicarage and are quickly dismissed. This is one of those books where the police are portrayed as ineffectual, the bumptious Chief Constable, Colonel Melchett, and the irritating Inspector Slack, a device often used to enhance the deductive powers and genius of the amateur sleuth.

Much depends on the actual time of the murder and the alibis of the suspects, of whom Miss Marple can think of seven. There are some intriguing subplots. Who is the beautiful new arrival to the village, Mrs LeStrange, and why is the doctor taking such an interest in her? Or was the murderer Protheroe’s flighty teenage daughter from his first marriage, Lettice who could not stand him? Was the Colonel’s murder anything to do with the imminent valuation of his silver collection for insurance purposes or, on a more mundane level, his proposed investigation into the church funds into which someone is dipping their hand?

The book concludes with a near-fatal attack on Hawes, poisoned and with a note confessing his guilt nearby. This discovery convinces Miss Marple that she knows who the culprit is and how Protheroe’s murder was committed. She lays a trap into which the culprit falls, confirming their guilt. The other loose ends of the tale are resolved in rather a twee ending.

The book is narrated in the first person and so we see events unfolding through the eyes of the vicar, Leonard Redding. This means that unless there is an abrupt change in the narrative, as in Richard Hull’s The Murder of my Aunt (1934), the vicar cannot have been the murderer and that he can only record events to the best of his knowledge and ability, leaving some of the leaps in logic in Miss Marple’s deductive process having to be taken on trust rather than be open to examination.

Christie writes in a light and breezy style, engaging the reader from the first chapter and not letting go. It is well-plotted, although not overly convoluted, and the attentive reader can probably work out whodunit, as well as being thoroughly entertained.

December 15, 2022

Another Helping Of Mince Pie

Cooks and bakers in the 17th century were keen to explore the potential of the mince pie, becoming ever more adventurous with their recipes. Thomas Dawson delighted his readers in The Good Housewife’s Jewel (1598) with a recipe for a spiced pie using the humbles or innards of a deer, while others used one or more of tongue, lamb’s stones otherwise known as testicles, udder, and tripe. Instead of meat some used fish, Markham including a recipe featuring pickled herring, while Robert May in 1660 put salmon, eel, and sturgeon in the same spiced pie.

Reflecting this spirit of experimentation, by Tudor times the spiced meat pie had become known as Shrid pie, a variant of which, Shred, was used as late as 1699 by Cumbrian chef, Elizabeth Brown, in her handwritten recipe book. The first recorded reference to mince pies, curiously, appeared in a document from 1624, locked away in the state papers of King Charles I’s then secretary of state, Edward Conway. It gives a recipe for “six Minst pyes of indifferent bigness”, the word “mince” derived from the Middle English verb for chopping finely, “mincen”. Of indifferent bigness they might have been to Conway, but the mix comfortably makes twenty-four modern-day mince pies.

There is no evidence that mince pies fell victim to Oliver Cromwell’s crack down on religious feasts and ceremonies, but that did not prevent his critics after the Restoration from claiming that he saw their rich and decadent spices as the epitome of Popery. A rhyme from 1661 fixed the canard in the popular imagination; “all plums the Prophet’s sons defy/ and spice broth’s are too hot/ treason’s in a December-pye/ and death within the pot”. Fake news is nothing new.

On Christmas Eve, 1663, Samuel Pepys noted in his diary that when he returned home, he found his wife making mince pies, while, three years later, on Christmas Day he went to church alone, “leaving my wife desirous to sleep, having sat up till four this morning seeing her mayds make mince-pies”. On his return he “dined well on some good ribs of beef roasted and mince pies”. Mince pies were not just reserved for Christmas. Attending a friend’s anniversary party, Pepys recorded that the centre piece were eighteen mince pies, one to mark each year of connubial bliss.

By the 18th century cheaper cuts of meat such as tongue and tripe replaced the traditional mutton, pork, or beef, and around the middle of the century an even more important change occurred, the transformation of mince pies from a savoury to a sweet dish. Hannah Glasse reflected this change in Art of Cookery (1747), instructing her reader to blend currants, raisins, apples, sugar, and suet. Before baking, the mix was layered in pastry crust along with lemon, orange peel, and red wine. Showing that meat was now optional she added, “if you chuse meat in your pies parboil a neat’s tongue, peel it, and chop the meat as fine as possible and mix with the rest”.

The availability of sugar at affordable prices, albeit at tragic human cost, led to a growth in the popularity of sweet pies, which by the 19th century were made with shortcrust pastry at the base and puff pastry at the top. Nevertheless, the tradition of using meat lingered on, Mrs Beeton feeling it necessary to include recipes in her Book of Household Management (1861) for mincemeat with and without meat.

By the 20th century, though, mince pies, now a firm Christmas favourite, were almost exclusively meat-free, the only vestige of their meaty heritage lingering in the name attributed to the filling, mincemeat. Even then, meat was used historically as a portmanteau word to describe foodstuffs in general rather than just animal flesh.

Whilst eschewing meat, today’s manufacturers still cannot resist the opportunity to tinker with mince pies to broaden their appeal, cheese pastry and Biscoff biscuit being amongst the flavours on offer this year.

Truly, they are pies for all seasonings.

December 14, 2022

Tom Brown’s Body

A review of Tom Brown’s Body by Gladys Mitchell

The lacunae in the readily available corpus of Gladys Mitchell’s work have meant that I have had to jump from the 19th in her Mrs Bradley series, Here Comes A Chopper, to the twenty-second, published in 1949, Tom Brown’s Body. As the title suggests, it is set in a public school, the fictional Spey School, although the murder victim is a teacher rather than a pupil.

This is one of Mitchell’s more accessible novels and is written with some verve, humour, sometimes biting satire, and, as usual, veers off into territory not normally travelled in the genre of detective fiction. Schools are not uncommon settings for fictional murders, but she adds some extra spice by exploring the world of witchcraft and the supernatural, not something one would immediately associate with the rarefied world of a minor public school.

Witchcraft is the pretext for Mrs Bradley’s presence in the first place, on the hunt for a book owned by her delightfully named ancestor, Mary Toadflax, who dabbled in spells and potions, a volume of which is in the possession of Spey’s local witch, Lecky Harries. While she is in the village, the body of a junior master of Spey School, Mr Conway, is found in the garden of another master. Conway had been hit over the head and then drowned. As there was no expanse of water nearby, the body had obviously been moved to the garden.

Conway is not a popular master either with the other masters or the boys. There is an element of casual racism and antisemitism running through the book. Conway is also a ladies’ man and has rented a room chez Harries for his romantic pursuits while another master, Kay, is a regular visitor there as he is pursuing an interest in witchcraft. Another master has spent all his spare time building a replica of a Roman Bath and it soon becomes apparent that this is where the teacher was drowned.

Mrs Bradley is brought in to establish what really has gone. There are a couple of pupils who played truant, stealing a master’s bicycle to go to a dog track and getting lost, finding their way to Harries’ house and witnessing a quarrel which resulted in a window being broken. Another pupil is a strong swimmer. What is the significance of a decapitated cockerel? Another form of the supernatural, a Tibetan devil-mask, is worn by someone who pushes one of Conway’s lovers down some steps at the school play. Has the murderer struck again?

Mitchell cleverly weaves the strands of witchcraft, the supernatural and life at a public school into an entertaining, if somewhat implausible, tale, a mix of psychological insights, deduction, and mumbo-jumbo. The plot is not overly complicated, at least by Mitchell’s standards, and, frankly, the culprit and the motive are reasonably easy to spot, although the howdunit is ingenious and makes for a dramatic and amusing finale.

She has managed to capture life in a school well and her leading characters are finely drawn. Her style is not as obscure and convoluted as in some of her earlier works, but she cannot resist wearing her encyclopaedic knowledge of ancient and modern literature on her sleeve. It was nice to see Aeacus get a namecheck and Itylus, whose myth formed the basis of Laurels are Poison, another appearance.

This is one of her better novels and is highly recommended.

December 13, 2022

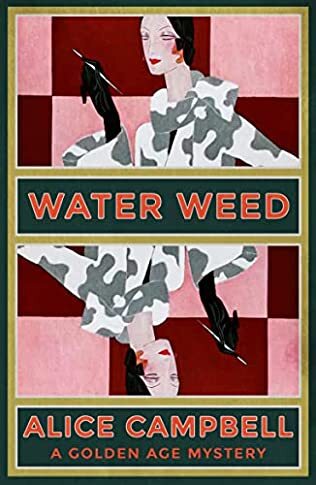

Water Weed

A review of Water Weed by Alice Campbell

What do you get when you cross Henry James with Patricia Wentworth? The answer might be Alice Campbell, if her second novel, Water Weed, originally published in 1929 and now rescued from obscurity by Dean Street Press, is anything to go by. This is the first novel by the American-born Campbell that I have read. A feminist and women’s suffragist she moved to France where she married James Campbell, and just before the outbreak of the First World War came to England where she stayed until her death in 1950. She wrote nineteen detective mystery stories.

The Jamesian influence is to be found in the characters, American ingenues who arrive in England and fall under the influence of more worldly-wise and grasping Europeans. The Wentworth influence can be seen in the nature of the story which is as much a romance as it is a piece of crime fiction in which the heroine, Virginia Carew, cannot believe the change that has come over her childhood friend, Glenn Hillier, who it emerges is enmeshed in a situation which could lead him to the gallows. Virginia is desperate to clear his name and, in the process, shows her true feelings for him.

Mercifully, we are spared the torturous and lengthy Jamesian sentences, but, alas, we also have to without Wentworth’s verve and story telling ability. This is a bit of a plod, perhaps a hundred pages too long, and, as Virginia is operating pretty much on her own, is full of introspection as she mulls over the latest development or decides what to do.

Virginia, though, does have the merit of being an interesting character. She is independent, determined, smart, and insightful, confident enough to take on the establishment in the form of the police and to prove that they have arrested the wrong person for the murder of a glamorous, middle-aged woman, “Cuckoo” Fenmore. However, she is also very gullible, quick to take anything anyone says at face value, and often ends up a blind alley and while she ends up on the right track, it is only thanks to the intervention of one of her prime suspects that her life is saved, and the culprit is caught. A smarter cookie would have wrapped the case up much more quickly and, I believe, Campbell did not use her as a sleuth in any of her other books.

The plot is fairly simple. Glenn has become part of the furniture at the Fenmores and has fallen under the spell of Cuckoo. Cuckoo’s estranged husband is always looking for ways of extorting money out of his wife and sees her dalliance with the younger man as an ideal opportunity. Gavin and Cuckoo are heard quarrelling one night and, in the morning, Cuckoo is found murdered and Gavin has run away. Virginia tracks him down to a lonely pub and persuades him to hand himself into the police. The police, who seem to take the easy way out, promptly charge him with murder and he does not help himself by refusing to reveal the reason for the quarrel. Virginia is determined to see justice done.

There is a dark undertone to the novel, the psychology of masochism, the power wielded by the masochist, without whom there would not be the opportunity for the sadist, and the masochist’s desire to push their boundaries. Once the reader recognises this, what happened chez Fenmore becomes clear. Even Virginia begins to get it. And the title refers to a dream/nightmare that Glenn had in which he is entrapped in a lake by water weed that holds him down, an allegory, of course, of his relationship with his femme fatale.

It is not a book I really warmed to= – it really needed a more aggressive editing and sharper focus – but I will read some more of her novels, now that they are back in circulation.

December 12, 2022

How Birthdays Explain Coincidences

G K Chesterton was dismissive of the idea of coincidences, calling them “spiritual puns”, but rationalists believe that these seemingly mystifying concurrences can be explained through the theory of probability. They use as their starting point the “Birthday Paradox”, the commonplace occurrence that still elicits surprise, finding we share the same birthday with someone else in the room. It can be easily explained.

Leaving aside the complications of leap years, the date of a person’s birthday is one of 365 possibilities and so the probability of someone not sharing that birthday is 364/365 or 99.73607%. Enlarging the group means that, while the probability of one person not sharing a birthday with one other person remains unchanged, there are more potential combinations to analyse, reducing the probability of someone not sharing a birthday with anyone else in the room. The formula becomes 364/365^n, where n is the number of people in the group.

The tipping point is a group of twenty-three where there are 253 combinations of dates and the probability of two people not sharing a birthday reduces to 49.952%. In other words, the odds are slightly greater of finding two people who share the same birthday than not. The larger the group, the more likely it is. Rather than be surprised when we find two people sharing the same birthday in a large group, according to probability theory, we should be more shocked if it does not happen. As for three people sharing the same birthday, the probability is greater than 50% in a group of 89 people, by which time, on average, ten pairs of people will be found to share the same birthday.

The financial sector attempts to assess the likelihood of something happening, the famed one in one-hundred or one in two-hundred-year events which appear to occur with increasing frequency, to ensure that it has enough resources to meet the anticipated consequences. As Sir Robert Fisher wrote in 1937, “the one chance in a million will undoubtedly occur, with no less and no more than its appropriate frequency, however surprised we may be that it should occur to us”. Sophisticated analysts worry about what Nassim Taleb dubbed in 2007 a Black Swan, an event so rare that even the possibility that it might occur is unknown, but one that has a catastrophic impact and can be explained in hindsight as if it were predictable.

Does this mean that we are simply actors in a drama directed by the Law of Large Numbers, where, as Diaconis and Mosteller noted, “with a large enough sample, any outrageous thing is likely to occur”, especially if we view events over a long enough timescale? Even at a personal level, given the number of people we know and all the places we go to and the places they visit, perhaps it should be more of a surprise if we do not bump into someone we know somewhere at some time. And should we count those near misses as coincidences, where we visit the same place on the same day as a friend but do not see them because we were there at different times?

Some people seem more attuned to experiencing or recognising coincidences than others. According to Desmond Beitman, those who describe themselves as religious or spiritual, or are likely to relate information drawn from the external world to themselves or seek meaning in events fall into that category, as are those who are extremely sad, angry, or anxious.

Others, though, seem to go through life either without experiencing coincidences or, at least, are oblivious to them. That does not mean that they do not encounter them, just that they fail to appreciate their significance, suggesting that coincidences must be recognised to be acknowledged. There is also a selfish aspect to coincidences. Ruma Falk, in her paper Judgment of Coincidences: Mine versus Yours (American Journal of Psychology, Winter, 1998)[1], found that, as is the case with dreams, people regarded their own coincidences to be more surprising and interesting than those of others.

Researchers have sought to categorise coincidences. Perhaps the most familiar are environment – environment, where something occurs that can be objectively observed, such as meeting someone who shares the same birthday or a friend in an unexpected place. Mind – environment coincidences are where you have a premonition about something and then it happens, such as thinking of someone who then, out of the blue, makes contact. Mind – mind coincidences are where, for example, we feel the pain or emotion of someone else at a distance, a sensation often experienced, but not exclusively, by twins.

For some, a rational, probability-driven view of the randomness of the world is just too binary to be compelling and one into which not all coincidences easily fit. One such was the psychologist, Carl Jung, who posited in his book Synchronicity (1952) that there was another force, “an acausal connecting principle”, which could provide a more complete explanation of coincidences. Synchronicity, he claimed, was “a certain curious principle…[which] takes the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance”. It also provided, he thought, an explanation for other phenomena such as extrasensory perception, telepathy, and even ghosts.

These two views of coincidence might not be compatible, but life would lose some of its mystery if it could be explained solely by a mathematical theory.