Martin Fone's Blog, page 105

November 11, 2022

Tread Softly

A review of Tread Softly by Brian Flynn

Taking its title from a line from W B Yeats, Tread Softly, the twentieth in Flynn’s Anthony Bathurst series, was originally published in 1937. According to Steve Barge aka The Puzzle Doctor, the man who rediscovered the sadly neglected Brian Flynn and in conjunction with Dean Street Press have painstakingly reissued them for a modern audience, this is Flynn’s masterpiece and the book which convinced him that it was worth trying to revive the author’s fortunes. There can be no higher praise.

The first thing to strike the reader is the unusual premise. Chief Inspector Andrew McMorran of the Yard and Anthony Bathurst in full Homesian mode are discussing the case of Claude Merivale, a film actor, who has voluntarily turned himself in, readily confessing that he has killed his wife, Vera. However, he claims that it was involuntary murder, being in the grip of a powerful and vivid dream in which he felt the need to defend himself. In doing so, he lashed out and strangled his wife. It seems a rather binary problem; either Merrivale is lying, and it is murder most foul, or it is an accidental, albeit tragic, death, one that could send shock waves amongst sleeping partners.

Flynn then uses a series of letters to throw some light on to the relationship of the Merrivales, firstly from Eve Lamb, the Merrivale’s housemaid who shows unshakeable loyalty to her dead mistress, then from Claude’s sister, Jill, who declares her devotion to her brother, and then from one of Claude’s fellow actors, Peter Hesketh, who pledges that the company is right behind him even though they seem to be coping well without him in bringing their latest film to a conclusion. The letters bare close reading as they do contain some hints and clues which as the novel progresses, become increasingly important.

Although McMorran and Bathurst do some sleuthing, unearthing a photograph of Vera with a man, presumed to be her husband but about which Jill finds some troubling detail, and a sighting of Merrivale returning home on the night in question considerably earlier than he had said, they do not get very far. In the absence of any new developments. The trial goes ahead. Here Flynn gives short pen pictures of the nine men and three women true, giving us some insight into their thinking. The defence, as masterful as is it is obvious, prevails and Merrivale, halfway through the novel is acquitted.

But that is not the end of the case and Bathurst refuses to be defeated, wracking his brains and carrying out further inquiries to get to the bottom of what really happened on that fateful night. A second murder gives him something to get his teeth into and the solution is ingenious. Although working alongside McMorran, Bathurst rather sours the relationship at the end, going rogue and playing judge and jury himself.

Along the way we have ill-fitting dentures, a complex family relationship, mistaken identities, a pair of duck white suits, a letter someone is anxious to recover, although its contents are never disclosed, someone who always seems to have got somewhere just before Bathurst, and much more. There are also some wonderful characters, none more so than Pike Holloway, a police constable who spotted Merrivale returning home early. He is delighted to sit at the feet of two masters of his profession and quaff beer in generous quantities while they discuss the nuances of the case. Inevitably, his evidence is not quite what it seemed to be.

Flynn has produced an intriguing mystery which keeps the reader on their metaphorical toes until the end and played around with the novel’s structure to introduce fascinating insights and perspectives. To my mind, the book’s weakness is motivation. Undoubtedly, people at the time had a higher sense of honour than prevails nowadays but would the indignities suffered really lead to murder? Nevertheless, it is highly enjoyable.

November 10, 2022

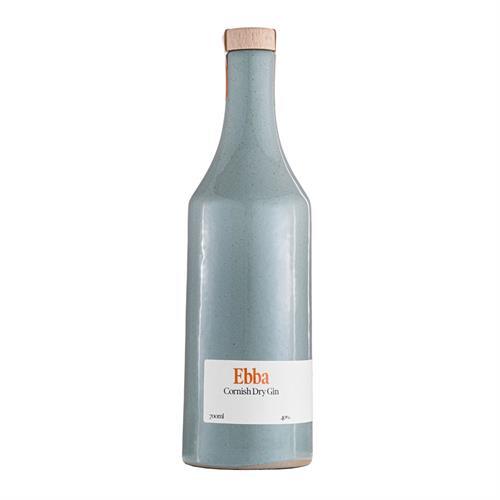

Ebba Cornish Dry Gin

One of Cornwall’s most stunning sights is St Michael’s Mount, a rocky island in St Michaels’ Bay complete with a mediaeval castle and church. Depending upon tides you can either walk there or back from Marazion or, when the tide is in, travel by boat. Be prepared for a bit of a climb when you get to the island but the terraced gardens, the castle and its art collection are well worth the effort. It also makes an impressive sight, looming up from the coast line.

As well as this famous landmark, Mounts Bay is also the home of Mounts Bay Distillery in nearby Praa Sands. A small family-run operation, the brainchild of Lisa Anglesjo and Ben Roberts, it is making waves with n impressive range of gins and rums, all inspired by their wonderful Cornish setting and featuring many of the county’s botanicals. As is the modern way, they eschew plastics in their products and donate shares of their profits to charities that plant trees and remove plastics from the oceans.

On a recent visit to Constantine Stores, the headquarters of Drinkfinder UK, I picked up a bottle of their Ebba Cornish Dry Gin. One of the ways of trying to make your mark in the crowded market spawned by the ginaissance is to create a bottle which is so stunning that it cannot fail to catch a browser’s attention. Mounts Bay Distillery have managed to pull this off with considerable aplomb. The bottle is stunning, simplicity personified, but elegant and something you will want to keep and cherish, long after the original contents have gone.

The bottle is slim, circular with a medium-sized neck, leading to a wooden top and cork stopper. What marks it out is both the material it is made of – it is ceramic – and its colour, a sort of duck egg green. Labelling is minimalist. A long thin strip near the base of the bottle, giving simply the name of the product, the size of bottle (700ml) and the ABV (40%) in orange and black type on a white background. The continuation to the rear of the bottle is marginally more informative. The only other colour used is orange on the security label. If you are looking for minimalist elegance, this is it in a bottle.

The label does tell me that it was “inspired by the ocean and the botanicals picked up along the shoreline”. While they do not give a full line up of the botanicals used, the bottle does reveal that this small batch spirit is distilled in a pot “with fresh citrus tangs from sea berries, heady pine tones from juniper and herbal notes from rock samphire and sea aster”. The sea berries are farmed and harvested by the Cornish Seaberry Company.

The fruits of their labours do not disappoint. There is enough juniper in both the nose and the beautifully clear spirit to keep an old stick-in-the-mud like me satisfied, while the citrus elements are crisp and zesty, and the shoreline botanicals give it a saline freshness which lingers into the aftertaste. A Cornish twist on a London Dry style, this is so moreish that even if it was served in a tin can, I would buy it. Fortunately, the bottle is an added bonus and will be kept to be used either as a water bottle or a stand for a candle. After all, we all need to do our bit for the environment.

Until the next time, cheers!

November 9, 2022

Died In The Wool

A review of Died in the Wool by Ngaio Marsh

This was a Roderick Alleyn murder mystery story, the thirteenth in the series and originally published in 1944, which left me a tad underwhelmed. It was a well-constructed, well-written tale but it seemed a little one-paced for my taste. Although set in Marsh’s home country of New Zealand, as was her previous novel, Colour Scheme, apart from the sheep, it lacked any local colour. Marsh also seemed conflicted as to whether it was a traditional murder mystery or a thriller and, in the end, it became a bit of both, never a recipe for success.

It is also a little unusual in that by the time Roderick Alleyn visits Mount Moon, the Rubrick’s remote sheep farm, Flossie, the wife and Member of Parliament, had been murdered fifteen months earlier and Archie, has died, of natural causes a year ago. It is the coldest of cold cases and much of Alleyn’s investigation is conducted by way of a family convention at which those living at the farm give him their recollections of the evening in question. It provides Alleyn an opportunity to make a character study of each of the key suspects and to understand the motivations for the murder. Most people in the room have reason enough to have killed her.

Terence Lynne’s amorous attachment to Archie had been discovered by Flossie shortly before her death and she cold-shouldered Terry and was overly amorous to Archie. Flossie had been cold to her nephew, Douglas Grace, who had been invalided with an injury to the gluteus maximus, since he raised his suspicions about espionage in the farm. Fabian Losse, invalided with a head injury which resulted in periods of mental instability, was sweet on Flossie’s ward, but he received no encouragement. Cliff Johns, son of the farm manager, who, because of his musical talent was taken under Flossie’s wing, had a falling out with her when Cliff was accused of stealing whisky. Markins, the manservant, also acts suspiciously although the reason for that soon becomes apparent.

Alleyn’s purpose for visiting Mount Moon is not principally to investigate the murder. He is still in New Zealand on a top-secret mission to root out fifth columnists and he is there because of a tip off that a secret project, upon which Grace and Losse, are working on at the farm, has been compromised. Of course, the murder and the security breach are intertwined but Marsh’s focus jumps between one and the other without settling upon which should be the story’s main focus.

As befits a Marsh novel, the death is ingenious. Flossie is killed in the shearing barn by a sharp blow to the head and then her body is placed in the baling machine for it to be wrapped firmly and securely in a bale of the Rubrick’s finest wool. It allows her to justify the rather weak pun that serves as the book’s title.

Flossie’s fate is nearly suffered by Alleyn, but the victim of the second assault, Fabian, made the mistake of wearing Alleyn’s overcoat. Mistaken identity, alibis dependent upon music, some marks on the floor, a stub of a candle, a lost diamond clip are what lead Alleyn to his conclusion and to prove his suspicions he sets a trap, with himself as bait, into which the culprit falls. In truth, there are only two, three at a pinch, credible suspects and the antecedents of one is enough to give the game away, but Alleyn is nothing if not thorough.

As a book it had its moments but was not one of Marsh’s best.

November 8, 2022

The Case Of The Gilded Fly

A review of The Case of the Gilded Fly by Edmund Crispin

A conundrum that dedicated followers of Golden Age detective fiction is face is whether to follow an author’s series in chronological order or to dip in and dive around. The advantages of the former approach is that you can see the author and main character develop, while the latter approach allows you to read their better novels first. For Edmund Crispin, the nom de plume of the music composer, Bruce Montgomery – he is credited with writing the scores of some of the early Carry On films – I am jumping around.

The Case of the Gilded Fly is Crispin’s first novel in his Gervase Fen series and was originally published in 1944. Enjoyable as it is, it is not a patch on The Moving Toyshop. Gervase Fen is a Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University and an accomplished amateur sleuth, who, the narrative reveals, has already notched up an impressive tally of successes by the time Crispin decides to introduce him to the reading public. His opposite number, Sir Richard Freeman, is the Chief Constable and an amateur literary critic with pretentions to greatness.

The book opens with an amusing account of the rigours of travelling by train from Didcot to Oxford, a clever device to introduce us to all of the main characters, who, coincidentally, are all travelling on the same train. The story is centred around a theatre group who are about to put on Robert Warner’s latest play. The group is a farrago of lovers and mistresses and there is the usual mix of personal and professional tensions. The focus of attention is a catty but beautiful actress, Yseut Haskell, who is superficially attractive to men but uses them as playthings and earns the enmity of her fellow actresses.

After a wild party, Yseut is found dead in a college room, another case of murder staged to look like a suicide. It is also a locked room mystery of sorts with plenty of suspects but none of whom seemingly had the opportunity of entering the room unobserved. And what was the significance, if any, of the Egyptian-style ring with a gilded fly which was inelegantly fixed to one of the victim’s fingers? It is also another of those stories where two of the suspects are listening intently to the wireless which is playing loudly and muffles any other extraneous noises.

Crispin is a witty writer and while he is at pains to put together a reasonably watertight and intricate plot, it is clear that he is poking fun at some of the genre’s more ludicrous conventions. Some writers, Patricia Wentworth, cannot resist adding a bit of romance into their stories but Crispin out Wentworths her by having almost all of the suspects coupling off, as if Yseult’s murder has opened the floodgates to allow Cupid to do his best.

Crispin, tongue in cheek, provides us with a plan of the crime scene, a detailed timetable of the suspects’ movements against which their alibis can be checked, and interrupts the narrative to tell the reader that something of import was revealed in the previous chapter. At the end of the first chapter, he tells us that by the end three people will be dead, one murder perhaps avoidable if Fen had followed his convictions, and the third death telegraphed by an account of a rogue safety curtain.

Fen tells us repeatedly that he had solved the crime within three minutes of knowing the circumstances, although he needed to garner proof, and while the clues are there, and, frankly, the culprit readily identifiable, the method of the murder is an ingenious take on a locked room.

Crispin has served up an enjoyable romp, it is wonderfully atmospheric and full of acute observations of Oxford life, peppered with quotations from poets both mainstream and obscure, has a lovely ghost story, and is reasonably, if not absolutely fairly, clued. The Gilded Fly has less importance than its role in the title suggests, and it seems to me this is a book where he is finding his feet, his better works yet to come.

November 7, 2022

Souling And Stingy Jack

“Souling”, a sort of religious insurance policy, was a feature of All Saints’ and Souls’ Days, described by John Mirk in a sermon dating to around 1380 as the time when “good men and women would this day buy bread and deal it for the souls that they loved, hoping with each loaf to get a soul out of purgatory”. Soon, though, the poor took the initiative, going around towns, knocking on doors and asking for a soul-cake or soul-mass-cake in return for prayers, cutting a woeful figure, or “to speak puling, like a beggar at Hallowmas”, as Speed noted in Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona (Act2 Scene 1).

By the 19th century, the baton had passed to children, at least in Shropshire, north Staffordshire, Cheshire, and Lancashire, going from house to house, singing a song and collecting money, food, drink, or whatever the household could spare. Versions of their songs have survived including this one recorded in Shropshire: Bye-gones Relating to Wales and the Border Country (1889/1890), which went “Soul, soul for a souling cake!/ Pray you, missis, for a souling cake/apple or pear, plum or cherry/ anything good to make us merry/ Up with your kettles and down with your pans/ Give us an answer and we’ll be gone”. However, by the mid-century in other parts of the country only “a few thrifty, elderly housewives still practice the old custom of keeping a soul mass-cake for good luck”, according to the contemporary historian, Michael Denham.

In Irish folklore Stingy Jack had a penchant for playing tricks on the Devil. After inviting him for a drink, Jack, living up to his nickname, refused to pay and persuaded the Devil to turn himself into a sixpence. Instead of using the coin, Jack pocketed it and kept it next to a silver cross, thus preventing the Devil changing back to his original form. Eventually Jack let him go on the proviso that he let him be for a year. On their next encounter Jack persuaded the Devil to climb a tree and pick an apple. While the Devil was up there, Jack carved the sign of the cross into the bark, trapping him. The Devil secured his release by agreeing to leave Jack alone for ten years and to not claim his soul when he died.

When Stingy Jack eventually died, he was refused entry into Heaven and the Devil kept his side of the bargain. Condemned to spend his afterlife roaming around the world, to light his way, he carried a lantern carved from a turnip, with a red-hot ember burning inside, a souvenir of Hell given to him by the Devil. Known as Jack of the Lantern or Jack O’Lantern, his ghostly light was often seen by the superstitious, although, more prosaically, what they probably saw were will-o-the-wisps, marsh gasses that glow in the dark.

For several centuries the Irish hollowed out turnips or mangelwurzels and carved scary faces into the external flesh. A candle was inserted into the hollowed vegetable, which, when lit, accentuated the ghoulish features of their creation. They were either placed in windows or carried as the revellers went out souling to frighten the unwary and to ward off evil spirits. There were even competitions, the Limerick Chronicle reporting in 1837 that a local pub held a competition at which a prize was presented for the “the best crown of Jack McLantern”.

In Worcestershire at the end of the 18th century turnips were carved to make “Hoberdy’s Lantern” while others used potatoes or large beetroots. The hard flesh of these vegetables made it a painstaking exercise and the Irish migrants to America must have been delighted to discover one of the country’s most distinctive indigenous fruits[1], the pumpkin.

Larger, with softer flesh and a hard exterior, they were much easier to carve and produced more impressive results. It was these characteristics that made gourds, one of the first cultivated plant species, a favourite for carving into lanterns around the world, particularly among the Maoris, one of whose words for lampshade also means gourd. Once pumpkins found their way to Britain, there was no turning back.

The renaissance of Halloween in the twentieth century might be for some an egregious example of the Americanisation of British culture, but its component parts have been with us for centuries, just in different forms.

[1] https://www.countrylife.co.uk/food-drink/curious-questions-is-a-pumpkin-a-fruit-or-a-vegetable-219743

November 6, 2022

Toilet Of The Week (35)

With public toilets as rare as hen’s teeth, any proposal to build some new ones has to be welcomed, but there is a stink brewing about a proposal to build a 150-sq-ft restroom with just one toilet in a town square in the Noe Valley area of San Francisco. It comes with a loodicrous price tag of $1.7m and will not be built until 2025 due to the city’s protracted planning processes. Only $750,000 of the $1.7m cost relates to actual construction costs, the other million dollars being spaffed on architect fees, project management, and surveying.

Even so, it is an eye-watering sum to spend a penny. Critics have pointed out that a 520-square-foot carsey was built in Gillette in Wyoming in just three months for the bargain basement price of $222,582 and it had six stalls, a mere $428 a square foot compared with the San Franciscan $11,333. However, others point out that that is the cost of building in Frisco and that the last two single-seater jobbies built in the city cost $1.6m and $1.7m respectively.

Perhaps a cheaper option will be to plant some bushes.

November 5, 2022

Art Critic Of The Week (6)

Modern abstract art, eh?

Mondrian painted his abstract work, New York City 1, in 1941, a series of adhesive tape lines in primary colours which intersect each other to create rectangles. It was first displayed at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1945 and since 1980 has hung in the art collection of the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia in Dusseldorf. For decades it has been hung to show the yellow, red, and blue lines thickening at the bottom, representing a skyline.

There is no signature on the painting and Mondrian, rather unhelpfully, did not put “this way up” on the back of his creation. Curator, Susanne Meyer-Büser, however, reckons that it has always been hung upside down, pointing out that a similar work of Mondrian’s, New York City on display in Paris, has the lines thickening at the top as does a photograph of the painting on the artist’s easel taken days after he died.

Now the hanging error has been pointed out, other art historians agree with her. It is too late to rectify the mistake, though. The adhesive tapes are extremely loose and hanging by a thread, according to Meyer-Büser, and if it was turned the right way up, they are likely to fall off.

That the mistake was not noticed for 75 years says a lot about abstract art.

November 4, 2022

Here Comes A Chopper

A review of Here Comes A Chopper by Gladys Mitchell

For those readers who like to follow the development of an author and their characters by reading their works in chronological order, there are some frustratingly large lacunae in the readily available books of Gladys Mitchell. Here Comes A Chopper, the nineteenth in Gladys Mitchell’s Mrs Bradley series, originally published in 1946, is the next book after Laurels are Poison (the 14th) that I could find in e-book format. Reading Mitchell’s Mrs Bradley series is not for the faint hearted but for a writer who is supposed to be a doyenne among crime writers, this seems a lamentable set of circumstances.

This is one of Mitchell’s more readable and accessible books. It almost seems that its lightness of spirit is a direct response to the end of the Second World War. However, it would not be a Mrs Bradley story without a dash of the weird, in this case two headless corpses and a novel place to hide a head in, some psychology – after all, Mrs Bradley is both an amateur sleuth and an acclaimed psychoanalyst – some mythology, and a narrative full of quotations from obscure poets. As an aside, as someone who is now almost dependent upon search engines to look things up, I am constantly in awe at the depth and breadth of Mitchell’s knowledge.

The title of the book comes from a line in the nursery rhyme, Oranges and Lemons, but also, clearly, a reference to the severing of the victim’s head. In essence, though, this is a country house murder mystery, and, by Mitchell’s standards, a fairly conventional one at that. The book opens with a schoolmaster and poet, Roger Hoskyn, looking forward to meeting up with his friend, Bob Woodcote, and going for a ramble in the countryside. However, Bob has injured his ankle and his sister, Dorothy, meets up with Roger to give her brother’s excuses – no mobile phones in those days – and agrees to be Bob’s substitute.

They get lost and stumble across a country house where they stop to ask for directions. They are astonished to be invited in to dinner, as the master of the house, Mr Lingfield, has gone missing and the hostess will not entertain the prospect of sitting down to a table of thirteen. After leaving the house and enduring a train journey on a branch line, they are picked up by Lingfield’s chauffeur, Sims, to take them home, although home turns out to be Mr Lingfield’s mansion. One of the house guests, inevitably, is Mrs Bradley.

The following day Lingfield’s body is found, naked and decapitated, but is it Lingfield and what happened to him and who committed the crime? Where is the head? Mrs Bradley sets out to investigate. There are red herrings, scars, assaults on poor Roger, some archery, a closed set of suspects, some eccentric and others hiding their emotions and jealousies, and a bewildering array of clues and hints which eventually lead to the resolution of the mystery.

There is a distinctly heavy dose of romance running through the tale. Roger, as befits a young man who has been educated and works in an all-male environment, is hopeless with women and seems to fall head over heels with any woman he falls in love with, first Dorothy, then the book’s femme fatale, Claudia Denbies, to whom there is more than meets the eye, and then Dorothy once more. Mitchell is an acute observer of the behaviour of those who fall in love and the ups and downs of nascent relationships.

It is a book full of humour, especially over the identification of a body that is both headless and naked, sharp observations, and, with Mrs Bradley on top saurian form with a mischievous glint in her eye, it is one I would recommend to someone looking to discover what Gladys Mitchell is all about.

November 3, 2022

Cornish Rock Gin

The quiet waters of the Cornish distilling world turned distinctly choppy in September when Nigel Farage launched a range of three Cornish gins made with “patriotic flavours” and featuring the man himself walking along a Cornish beach with his Labrador. Detractors expected it to be full of promise but leaving a bad taste in the mouth, but what caused a stushie was his comments that he had worked with Cornish artisans to produce his contribution to the ginaissance.

Distillers from the county all disclaimed responsibility but it eventually emerged that the tight-lipped artisanal collaborators were George and Angie Malde from the Cornish Rock Distillery. Their distillery is just off the A30 north-west of St Tudy, near Rock. The idea of creating the distillery, which started as a “little hobby” came to the couple as they walked their dog, Blue, along the beach at Rock. The couple’s ambition was to distil gin in small batches using natural Cornish spring water from their own deep-water source and fragrant botanicals of the highest quality, some of which Angie forages herself.

The Maldes use a still, named Bonanza Boy after their favourite racehorse, which now produces an impressive array of eight gins and eight rums, each batch of which is meticulously tested, hand-bottled, stamped, and inspected one more time before being released for sale. As the recent furore has demonstrated, they also engage in third party distilling. The business has grown to such an extent that they now employ seven people and are in the process, at the time of writing, of moving into bigger premises.

Their first gin was Cornish Rock Gin, a bottle of which I bought on a recent trip to Constantine Stores, the headquarters of Drinkfinder UK. On the lookout for local Cornish gin I had not tried before, my eye was caught by the strikingly elegant bottle. Made of clear glass, it tapers outwards slightly from the base, with four sides and rounded edges, leading up to an almost flat shoulder, a small neck, and a dark brown cap with a cork stopper.

The labelling makes good use of a black background with gold and white lettering, which oozes class. The front tells me that it has a none too shoddy ABV of 42% and my bottle was number 176 from batch no 27. Unusually, and gratifyingly, the Maldes are not tight-lipped into what goes into what they describe as “the result of their quest to uncover the true spirit of Cornwall”. The line-up of botanicals consists of juniper berries, orris root, orange and lemon peel, pink peppercorns, celery seeds, and liquorice root, an intriguing mix.

On the nose there is a reassuring mix of juniper, citrus notes, and more earthy elements. In the glass the spirit is clear and while the earthiness of the juniper, the creaminess of the angelica, and the bite of the peppercorn are evident, the principal characteristic of the gin is of refreshing citrus. It is smooth with a lingering aftertaste. For my taste the citrus could have been toned down a little, but it is a welcome addition to my gin collection.

Despite the furore their recent associations have caused, Cornish Rock Distillery’s products are definitely ones to try out. Only seven more gins to go!

Until the next time, cheers!

November 2, 2022

Sudden Death

A review of Sudden Death by Freeman Wills Crofts

Freeman Wills Crofts started off his Inspector French series in 1924, which ultimately ran to 30 novels, the last published in 1957, with Inspector French’s Greatest Case, a title designed to lower expectations of the subsequent books if there ever was one. Sudden Death, originally published in 1932 and reissued by HarperCollins, if a tad expensively, could hardly be called one where French covered himself in glory. Although thorough in following all the leads and ingenious in discovering how the murders were committed, nonetheless it took an inadvertent slip of the tongue for the culprit to unmask themselves.

That said, it was an enjoyable story, Crofts treating his readers to two locked room mysteries in one book. Sybil Grinsmead, sickly and neurotic, is found in her gas-filled bedroom. The immediate suspicion is that is suicide, but French’s tenacity not only reveals that the unfortunate woman was murdered but also that the crime was committed by an ingenious, if somewhat Heath Robinsonish device. It would not be a Wills Crofts’ novel without a detailed drawing of the device, although, frankly, the more detailed look makes it seem even more incredible that it worked in the heat of the moment.

The second death is also staged to look like suicide, the master of the house, Severus Grinsmead, is found lying in his study, shot with a gun with his fingerprints on lying nearby. Of course, the study door had been locked and had to be broken down and there was no obvious way that the murderer could have left the room. However, though it looks like suicide, it is another cleverly staged murder and the resolution of how it was done is not as ingenious than the first.

Unusually for a Crofts crime novel, this is set in a country house, Frayle, where Anne Mead arrives to take up a job. Although Mrs Grinsmead is a little satnd-offish Anne strikes up a rapport with her and is convinced that she was not disturbed enough to have taken her own life. There are precious few suspects and there is a marked change in approach from other books of Crofts that I have read, where the canvas is broad and the investigations are wide-ranging. Instead of poring through railway and tide timetables, French has much more of an opportunity to make a character study of each of the residents, including household staff, but, even so, struggles to take a definitive view of whodunit, although towards the end the light begins to dawn on him.

I imagine that Crofts had hoped that the revealing of the culprit at the end would take most readers by surprise, but the attentive reader, and I find with him that it pays to be attentive, will have noticed the odd clue along the way. The motivation for the murders, though, is less well signposted.

In novels such as these I enjoy the little period details. It is set in the Depression when jobs are hard to come by. Uppermost in the minds of the two principal servants, Anne Mead and Edith Cheame, with unemployment figures so high is the terrifying prospect of having to enter the labour market again, if the house is shut down following the deaths, first, of the mistress and then the master.

Stylistically, Crofts decides to narrate the proceedings through the eyes of two of the principal character, Anne Mead and Inspector Joseph French. This breaks up the narrative, allowing us to see fresh perspectives and ensures that detailed investigations into alibis and the following up of clues that usually end up at a dead end is not as wearing as in some of his books. I got the sense that having set up his stall as a writer who specialised in the construction and breaking of cast-iron alibis, Crofts was experimenting, trying to break out.

He has succeeded in writing a novel that is both enjoyable and entertaining and, because of the dual perspective of the narrative, is lighter and less tiresome than some, but it is not as ingenious or as complex as when he is on top form.