Martin Fone's Blog, page 99

January 9, 2023

The Cafetière – A Refill

Calimani and Moneta’s design was further enhanced by adding a metal or rubber edge on the filter, effectively what we now know as the plunger spirals. A French kitchen equipment manufacturer, Melior, adopted their design to launch the Melior Coffee Pot in 1933. The pots made their way to Britain, appearing in the Army and Navy Stores catalogue from 1935, promising purchasers a method of brewing coffee as easy as making tea. Silver-plated, they sold in three sizes, four, six, and eight cups at 14/6, 17/6, and 21 shillings respectively.

A further refinement to the mechanics of a cafetière was made in 1936 by Italian designer, Gemma Barelli Moreta, who fitted a spring around a metal disk that sat above the filter, producing a much tighter seal. This was incorporated into the Melior design, which was now classically simple with an elegant art deco Bakelite handle, a statement piece on any upper-middle class table. Melior also produced ceramic cafetières in green, brown, blue mist, and gold and later, in the early 1950s, with glass containers.

Swiss-Italian designer, Faliero Bondanini, revolutionised the design of the cafetière, giving its iconic look of glass container, domed steel lid, and metal plunger. His design, which he patented in 1958, ensured that the device was much easier to clean, had a much better filter fit, trapping the sediment at the bottom, and a sieve to prevent the grounds from being poured into the cup. Melior adopted Bandanini’s design, marketing it as a Chambord, a name possibly derived from the roofline of the Château de Chambord.

By this time Melior was part of the larger SAE Martin group who took responsibility for distributing the Chambord around Europe, including Britain where they were sold by Fortnum & Mason for £3 2s 7d. During the 1960s it slowly became a household name in Europe, its desirability heightened when Michael Caine used one in the 1965 film, The Ipcress File.

Britain, though, proved a harder nut to crack. A major investor in SAE Martin, James de Viel Castel, used his Holywell-based company in North Wales, Household Articles Ltd, to produce a cafetière for the British market, similar but not identical in design to the Chambord. Known as La cafetière, it was launched in 1969.

Positioned as a high-end, aspirational product, it was stocked at John Lewis, Harrods, Selfridges, Fortnum and Mason and advertised in Country Life. The advertisements stressed the similarity to making tea and implied a touch of continental sophistication by “making coffee as the French do”. They hedged their bets by pointing out it could be made to use tea too, a smart move as Britain was still predominantly a nation of tea drinkers.

For those who baulked at paying £6 15s for a standard chrome plated La cafetière or £9 12s for the gold-plated model, there was another way to get their nicotine-stained hands on one. Embassy included them in their cigarette coupon catalogues in the early 1970s. It was not until 1990 that Argos began to offer an eight-cup model in their catalogues in 1990, priced at £38.50.

In 1991 the Danish company, Bodum Holdings, who were the distributors of cafetières in Denmark, bought the rights to the Chambord name from SAE Martin. Under their direction Bodum Chambord quickly became a symbol of excellence, a high-quality state-of-the-art coffee maker. Household Articles were allowed to retain the right to sell them.

With the growth of consumerism in 1990s Britain and a desire to explore new products and to eschew convenience for quality, the cafetière finally came into its own. Today it is the most used brewing device in the United Kingdom, even if, as recently 2012, 65% of the respondents to a Nespresso survey claimed they were too complicated to use.

After its battle for acceptance, the cafetière seems to be here to stay.

January 8, 2023

Art Critic Of The Week (8)

While visiting the Picasso Museum in France, a 72-year-old woman noticed a blue jacket hanging on a peg and thinking it abandoned and taking a shine to it, took it home with her. The sleeves, though, were a little too long and so she asked her tailor to take 30cm off them.

The collar, though, was perfect which was just as well as it was felt by the Gendarmerie who had tracked her down through CCTV footage and the debit card she had used to purchase her ticket. It turns out that the jacket was far from discarded but a piece of work by the Spanish artist, Oriol Vilanova, entitled Old Masters which recreated a jacket worn by Picasso in his studio.

The woman explained her mistake, was let off with a caution, and the somewhat truncated jacket was returned to the museum.

Vilanova was less enamoured with the impromptu alteration to his masterpiece and was said to be struggling to come to terms with the theft. Still, the artistic temperament will always try to find a bright side. “What interests me most is the attitude of the person who took it, the gesture of appropriating it and having it remade to measure. There’s the whole idea of reproduction and appropriation that is implicit in the work itself, but taken to a higher degree,” he said.

On the other hand, what interests me most is whether a jacket hung on a peg is really art.

January 7, 2023

Dildo Of The Week

Doctors were left shell-shocked when an 88-year-old man turned up at the Hôpital Sainte Musse in Toulon with an unusual complaint; he had an eight-inch long First World War artillery shell stuck up his anus which, he claimed, he had inserted for pleasure His arrival prompted a call for bomb disposal personnel, the evacuation of the adult and paediatric emergency unit, and the diversion of incoming emergencies.

Once the authorities had satisfied themselves that the shell was not live, they proceeded to remove the two-inch wide shell by performing abdominal surgery. As one doctor remarked, “it rarely comes out from where it comes in”.

The man, unnamed to spare his blushes although red cheeks were the least of his problems, was recovering well and said to be in good health.

You have to take your pleasures where you can, I suppose.

January 6, 2023

The Click Of The Gate

A review of The Click of the Gate by Alice Campbell

I am still not sure about Alice Campbell. The Click of the Gate, her fifth crime fiction book, originally published in 1932 and now reissued thanks to the sterling efforts of Dean Street Press and Steve Barge, is part thriller, part romance with a bit of detection thrown in. It is enjoyable, albeit a bit predictable and a tad overlong.

The central plotline is intriguing enough and is set in Paris. The 15-year-old daughter of Iris de Betincourt mysteriously disappears into thin air in the few seconds that it took her to get out of a car, open and shut the gate to her house, from which the book derives its title, and before reaching the front door, which her mother had opened to welcome her return. There were no signs of a struggle, and the girl uttered no scream. What had happened to her?

The de Betincourts were estranged, and Iris was seeking a divorce, not least because she was falling in love with Alan Charnwood, from whose perspective the story is seen, although Campbell, rightly, chose to write the story in the third party. Charnwood, who was due to travel down to Marseilles and then pick up a boat to Uganda to resume his military service, changes his plans to console Iris and to help solve the mystery and return the girl to her mother.

Others seem anxious to get Charnwood out of the way and even though he has been granted compassionate leave, he keeps receiving communications to return to active service straight away. Fortunately, in a rare outbreak of good sense he decides to check the veracity of the recall, no easy matter in a time when telegrams and the uncertain connections of the telephone system were the only speedy means of communication.

Although a metaphorical brick and anxious to help a damsel in distress, he is a bit dim, taking the wrong course or failing to interpret the evidence of his own eyes. Fortunately, he bumps into Tommy Rostetter, an American journalist in Paris and for a crime novelist who has no series sleuth, is one of Campbell’s occasional detectives. He beavers away in the background, throwing up more acute observations of what is going on, often to the blinkered dismay of Charnwood, and working alongside Inspector Maupin manages to unravel a plan which involves kidnap, extortion, and, of course, a large inheritance.

There is a rather picaresque husband and wife duo who flit in and out of the story and it is quite apparent that they are heavily involved in the girl’s fate. Campbell cleverly establishes an atmosphere where not everyone is necessarily who they appear to be, especially the character of another American in Paris, Helen Roderick. Is she feeding information back, wittingly or unwittingly, to the kidnappers and is she really the friend to Iris that she appears to be?

As the narrative unfolds it is clear who is involved in the plot and why, but the fate of the girl is unresolved until a dramatic denouement which is both thrilling and well told, the highlight of a book that had hitherto failed to get out of third gear. Rostetter also comes in handy in solving a moral dilemma of how much of the truth should get out into the public and private domain. The power of the pen, indeed.

The loose ends around Charnwood’s romantic aspirations are tidied up in the end and even for a hard-hearted old codger like me slightly heart-warming. The book just needed a bit of va-va-voom which, perhaps, a narrative with a wider perspective might have given it.

Still, more Alice Campbell is on my 2023 TBR list.

January 4, 2023

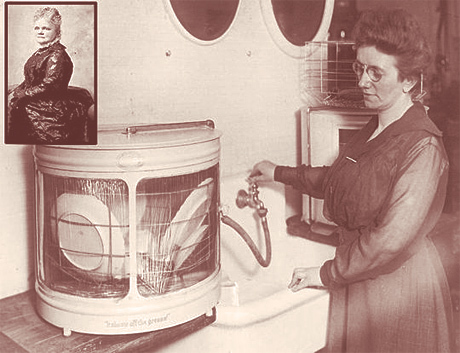

Clumsy Servants, A Socialite, And The Dishwasher

The dishwasher’s story began over 170 years ago, when a patent was granted to New Yorker, Joel Houghton, on May 14, 1850 (No. 7.365) for a device, which cleaned automatically what were quaintly described as “crockery and other table furniture”. Dishes were placed into a custom-made wooden box and washed “by turning a shaft with arms and buckets so arranged as to throw the water on the crockery with force, and thus acting upon and cleansing each and every article”. L A Alexander improved the design in 1860, adding a geared mechanism that span racked dishes through a tub of water.

These early versions of a dishwasher were neither very effective nor financially successful. It fell to a socialite from Shelbyville, Illinois, Josephine Garis Cochran, to produce the first commercially viable hand-powered dishwasher. She used to hold grand dinner parties, delighting in bringing out her fine collection of china and porcelain, some of it dating to the 17th century. To her dismay, though, while washing up, her maladroit servants frequently chipped them.

In desperation, Josephine decided to wash them herself, but she was just as clumsy as her servants. Wondering whether this wearisome and delicate task could be automated, she vowed that “if nobody else is going to invent a [mechanical] dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself”. True to her word, with the help of a mechanic, George Butters, she built a prototype in the shed behind her house, which she patented on December 28, 1886 (no. 355,139).

Josephine described her machine as one “in which a continuous stream of soap suds or clear hot water is supplied to a crate holding the racks or cages containing the dishes while the crate is rotated so as to bring the greater portion thereof under the under the action of the water”. The crate sat on a wheel powered by a hand crank and was showered with water infused with soap held in a container at the bottom of the machine. Unlike the earlier models the machine relied on water pressure to clean rather than brushes.

Cost put the machine beyond the pocket of most households, a point recognised by Josephine who reflected that “when it comes to buying something for the kitchen that costs $75 or $100, a woman begins at once to figure out all the other things she could do with the money”. As most housewives had yet to put a value on their time, Josephine turned her attention to restaurants and hotels. Her first sale, in 1887, was to the prestigious Chicago hotel, Palmer House, whose manager was impressed at its ability to clean 200 dishes in two minutes.

The Garis-Cochran Dishwashing Machine made quite a splash at the Chicago World Fair in 1893, impressing the judges so much that they awarded it the top prize for “best mechanical construction, durability, and adaptation to its line of work”. This accolade produced a flood of orders from the hospitality industry, allowing Josephine to set up a factory near Chicago. Other companies followed suit, taking her basic design for their appliances but powering them with steam that passed dishes under jets of hot water on a conveyor belt or spinning basket.

Developing a commercially successful dishwasher for the home proved a tougher nut to crack. In 1924 British inventor, William Livens, produced a small, non-electric dishwasher aimed at the domestic market, which came with a door at the front to make loading the dishes easier, a wire rack to hold them, and a rotating sprayer, all familiar features today. Dishes were still washed but not dried, a problem Livens solved in 1940 when he added a drying element. Meanwhile in Germany, Miele launched a top-loading electric dishwasher aimed at the domestic market in 1949.

Miele’s plans to conquer the domestic market were scuppered by the Wall Street crash, with fortunes lost and disposable income too precious to spend on luxury items. In Britain the cost of Livens’ machine limited its market potential to the upper strata of society. As domestic servants were still plentiful, there seemed no need to mechanise a well-staffed process. Water supply was also an issue. While British houses increasingly had access to a permanent water supply, low water pressure and the limited capacity of hot water tanks made a dishwasher unviable in many houses.

In the 1950s the domestic dishwasher, now smaller, more convenient, and affordable, was perfectly positioned to make its mark in a world where the servant class had all but disappeared, and where working women, valuing their leisure time, were attracted to aspirational labour-saving devices. The improved quality of housing with a more consistently pressured permanent water supply also helped.

Eternity Ring

A review of Eternity Ring by Patricia Wentworth

Originally published in 1948, Eternity Ring, is the fourteenth in the Miss Silver series from Camberley’s finest, containing many of the traits one has come to expect from a Wentworth murder mystery. It is part thriller, part romance with her amateur sleuth knitting away in the background, closely observing what is going on, using her acute insights into human behaviour to draw conclusions which lead to the unravelling of the mystery, much to the chagrin of Inspector Lamb and the delight of her number one fan, Sergeant Frank Abbott.

It is Frank Abbott whose family provides the mystery. His cousin, Cicely, has left her husband of a few months, Grant Hathaway, without explanation and returned to her parents. Their house is near to Dead Man’s Copse in which there is a deserted cottage. One evening a cosy village tea party is interrupted by the dramatic arrival of Mary Stokes who says that she has just seen the body of a woman, dressed in black and with one earring made from an eternity ring and diamonds. When the police accompany her to the site, there is no body.

The body is eventually found, thanks to Miss Silver’s research, in the cellar of the deserted cottage. Soon Mary Stokes herself is murdered. Suspicion immediately falls upon Grant Hathaway who is known to have financial problems and Cicely’s inheritance was allegedly the driving factor for his marrying the otherwise plain girl.

Eternity Ring is another of Wentworth’s novels which explores the post War impact of individual actions that occurred in the theatre of war, this time the despicable crime of stealing the only valuables, in this case jewels, of a refugee fleeing the oncoming German forces. From this distance it might appear to be low down on the list of atrocities carried out during the Second World War, but it was probably an infrequent but reprehensible enough crime to generate some post war wringing of hands.

Hands form an important part in the resolution of the mystery as the initial victim who had visited Hathaway shortly before her murder had indicated that she could recognise the thief from their distinctive hands. There are just three suspects, Albert Caddle representing the lower orders, Hathaway, and Mark Harlow. That is being generous as the third was never likely to have been the culprit. Each have distinctive features on their hands, a scar, a part missing from a digit, and a stretch appropriate to their profession. I remember Sir Willard White – he was just plain Willard in those days – paying my wife a compliment by remarking that she had pianist’s hands.

Unusually, the murder victim did not deserve to die, her murder compounding the sense of injustice that she has suffered from her slayer. Whether her threat to reveal the identity of the thief who had stolen her jewellery when she was in extremis would really warrant silencing her forever is debatable. Having killed once, the prospect of dancing the hemp jig is not deterrent to strike again.

Having complained in my last review that Christopher Bush had not played fair with his readers in The Case of the Climbing Rat, Wentworth does the reverse, serving up a case where the identity of the culprit is as plain as a pikestaff, even if the motivation, or at least part of it, is a little harder to deduce. Cicely is one of Wentworth’s frustrating heroines, the pretext for leaving her husband turns out to be pretty feeble, over-emotional and a sign of considerable immaturity. The volte-face in her attitude to him is almost as unbelievable and her dash to his side almost leads to her own undoing.

Suspects may be thin on the ground, but there are characters in the story by the charabanc load, there to add colour without adding much to the plot. Two that I had high hopes of, Miss Vinnie whose tea party Mary Stokes burst into, and Maggie Bell, the invalid who amuses herself by listening in to the party line that all the villagers seem to share, but they come and go without making much of a contribution to the story.

For all that, Wentworth knows how to write a cracking story which keeps her reader entertained, and it is easy to shut your mind off from the absurdities of the plot. I left the book with two lessons: a slip of the tongue can be costly and always show the right letter to someone.

January 3, 2023

The Case Of The Climbing Rat

A review of The Case of the Climbing Rat by Christopher Bush

Originally published in 1940 but written a year earlier, this, the 22nd in Bush’s Ludovic Travers series, now reissued by Dean Street Press, is the second novel on the trot that is set in a France that was to change dramatically during the Second World War. Once again Travers is sucked into an intriguing case, courtesy of his new wife, Bernice, or rather a rogue uncle of hers, Gustave Rionne.

Rionne was a surgeon but was struggling to make ends meet, having been suspected of performing an abortion and botching a plastic surgery procedure. He had begun writing letters to Bernice, asking for money, his overtures becoming more insistent and threatening. Having told Travers of her concerns, as all new husbands will do he decides to go to France to “have a word” with the recalcitrant uncle.

As is often the way in a Bush novel there are two or more seemingly unconnected strands at the start which become increasingly intertwined as the story progresses. The second strand involves a notorious French serial killer, Armand Bariche, who was supposed to have died in a fire, after a successful spree of fleecing wealthy women and then killing them. Inspector Gallois, whom we have met in a couple of previous Travers’ escapades, has had a tip off that Bariche is alive and well and in the south of France. Gallois travels there in the hope of meeting the informant and get the information he needs to capture Bariche, an arrest that would be a considerable feather in his chapeau.

Travers was due to meet up with Gallois in Paris, but, surprise, surprise, the two bump into each other in the south of France as they go about their disparate business. Matters take a darker turn when Uncle Gustave is murdered, ingloriously stabbed to death in a public toilet while in the act of urinating. On the way to meet the informer, Gallois’ assistant, Charles Rabaud, is involved in a mysterious car crash and is taken in by a kindly doctor and his sister. Then a Swiss national, Georges Letoque, is found murdered, shot dead in a villa he had rented.

Then there is a travelling circus whose star attraction is a troupe of acrobats and a rat, who is trained to clamber up a rope to join his keeper. Only on one occasion he steadfastly refuses to play ball, a novel twist on the detective fiction trope of a dog that either does or does not bark.

Out of these disparate strands Bush eventually makes a coherent story, although it only begins to make sense at the end when the scales begin to fall from Gallois’ and then Travers’ eyes. Of the characters in Bush’s complex plot not everyone is as they seem, but the reader would be hard pressed to identify the culprit and the motivation.

The story also allows Travers to meditate on the black and white nature of capital punishment. Is someone who rids the world of a brutal and callous serial killer deserving of the same ultimate fate as would have been meted out to the serial killer had he been caught? That is one of the many problems of capital punishment, of course, a matter that in some countries, at least, could only be resolved well after the end of the Second World War which was to engulf Europe.

For the armchair sleuth this is a frustrating tale, but it is enjoyable enough as a piece of entertainment and just shows that while you can choose your friends, you cannot choose your family.

January 2, 2023

The Cafetière

A heatproof jug, usually made of glass with a plunger attached to the lid, the cafetière offers a convenient way to make tasty coffee for several people at the same time. Its adherents claim that by slowly and steadily depressing the plunger, the grounds and their all-important oils are completely saturated, allowing the drinker to appreciate the coffee at its best.

While drip machines and percolators heat the water up quickly, it cools just as quickly so the optimal temperature is only reached around the midpoint of the brewing process. The cafetière, though, maintains the right temperature throughout the process. And in these environmentally conscious days there are no pods or filter papers to dispose of, the spent grounds can go into the garden. The only disadvantages are that the glass can break and because it is not insulated, the coffee does not keep warm for long.

Cafetière is the generic noun for a coffee pot in French, its use not restricted to a particular design. In English it is used exclusively to describe a glass jar with a plunger used for making coffee, a device known in North America as a French Press, in Australia as a Coffee Press or Plunger, and in Germany as a Kaffeepresse. Its origins are shrouded in some mystery.

Someone somewhere must have worked out that plunging coffee grounds through hot water made for a tasty beverage. According to one account, almost certainly apocryphal, an old man in Provence, who mistakenly had added coffee grounds to boiling water and to his consternation saw them floating to the top, had the presence of mind to press them back down again using a stick and a piece of metal. Not only had he rescued his coffee, but it tasted wonderful. Et voilà, the cafetière was born.

The first registered patent for a device resembling a cafetière was granted to the French duo of Henri-Otto Mayer and Jacques-Victor Delforge in 1852. The accompanying drawing shows a solid metal jug, looking like a teapot, with a moveable metal filter. There was one inherent design problem. The plunger did not fit perfectly in the container, which meant that some of the grounds floated back up and ended in the cup, a flaw that took several decades to resolve.

The first popular and commercially successful cafetière did not appear until 1913. Designed by Louis Forest, the Cafeolette was a small pot with a piston with a basic metal filter with small holes in it. Instead of using hot water, warm milk was poured over the coffee grounds, left for a couple of minutes and then the plunger was pushed down to the bottom to produce a café au lait. It sold well in Parisian department stores such as Bon Marché and Printemps.

Meanwhile in Italy, Ugo Paolini had developed a device which used a plunger to extract juice from tomatoes. He saw an application for his device in coffee making but passed the baton over to the Italian duo, Attilio Calimani and Giulio Moneta. They developed and patented in 1931 an “apparatus for preparing infusions, particularly for preparing coffee” included “a slidable filtering member having a fit sufficiently tight…that causing…[it] to slide towards the bottom of the vessel the infusion will be rapidly filtered to get it ready for use” (US Patent 1,797,692).

Next time, we will see how its design was further refined to become the iconic piece of kitchenware.

January 1, 2023

Gin Resolutions

Here are my hopes for the gin world for 2023.

Survival of the fittest

With rising energy costs and the cost-of-living crisis, you do not to be a genius to realise that the artisan gin world is going to have a tough time with many lucky to come out the other side with a business intact. Let’s hope that as many as possible survive, especially those that bring something distinctive and refreshing to the market, survive to tell the tale and resist the siren calls of the big boys.

More information for the consumer

The other side of the coin is that the consumer will have less spare cash to make impulse purchases and will increasingly stick with the tried and tested. Gins that command a premium price will be seen even more as a luxury item, a treat. There is even greater incentive for distillers to be more up-front with the identity of the botanicals they use and the flavour profile, stripping away the marketese to give the prospective consumer an honest description of what is inside the bottle. While the precise calibration of botanicals is, rightly, a trade secret, it is not too much to expect a complete list of botanicals rather than a select number plus “special ingredients”. Distillers who are open about their product are more likely to survive.

Industry standards

With too many products marketed as gins that are either not gin by the generally accepted definition, having an ABV of 37.5% or above, or where the juniper has been so dissipated that it has waved a white flag and surrendered, there is a very strong case for a strengthening of the criteria for a gin to be so classified. At the same time, a standard flavour profile could be agreed on and distillers encouraged/forced to include it on their labelling. It is getting a bit of a Wild West out there and serious distillers and gin enthusiasts would welcome such steps. Let’s hope 2023 sees some progress on this.

Until the next time, cheers!

December 31, 2022

Gin Awards 2022 (3)

Bottle Design of the Year

I have long been fascinated by the design and shape of gin bottles, a sure fire way to get your product noticed in the crowded field spawned by the ginaissance. Here are my two favourites, and they are diametrically opposed in concept and execution.

Artingstall’s Brilliant London Gin

The paramount statement piece of this gin and what makes Artingstall’s stand out from the crowd is the bottle. It is stunning, a huge, square block of embossed glass, reminiscent of the classic cut glass decanters of the 1950s and 60s, which would do serious damage if you dropped it on your toes. The design was based on an old cut-glass decanter Feig found in a charity shop and has a wide glass top with a white synthetic stopper. The labelling is a classy black, textured with a gold foil border and gold lettering. It is magnificent.

I cannot bear to part with it and even though its contents have long gone, it stands proudly amongst my gin collection.

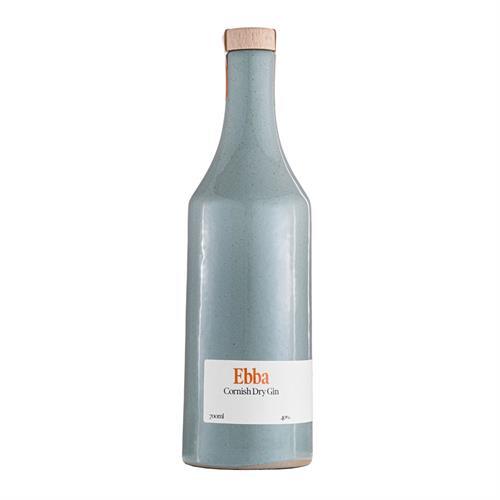

Ebba Cornish Dry Gin

Mounts Bay Distillery have managed to grab the browser’s attention in a completely different way. The bottle housing their Ebba Cornish Dry Gin is stunning, simplicity personified, but elegant and something you will want to keep and cherish, long after the original contents have gone.

Slim, circular with a medium-sized neck, leading to a wooden top and cork stopper, it is made of a sort of duck egg green ceramic. Labelling is minimalist. A long thin strip near the base of the bottle, giving simply the name of the product, the size of bottle (700ml) and the ABV (40%) in orange and black type on a white background. The continuation to the rear of the bottle is marginally more informative. The only other colour used is orange on the security label.

If you are looking for minimalist elegance, this is it in a bottle.

Logo Of The Year

The revamped 58 and Co have come up with a stunning logo that took my breath away. Elegant in a contemporary style, it features a hand-drawn juniper leaf dipped in copper, an image drawing its inspiration from the copper sun-powered alembic still used in the production process. The gin is good too, especially their Navy Strength.