Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 36

October 20, 2021

Misfits, by Michaela Coel

This short book is an extended version of Michaela Coel's 2018 MacTaggart lecture, an outsider's view of the television industry,. I'd seen that at the time but it's interesting to revisit given the stuff on early British television that I've been reading (The Intimate Screen and Writing for Television (1955)), about the variety, the diversity, of what gets put on TV - and who decides what gets put there.

This short book is an extended version of Michaela Coel's 2018 MacTaggart lecture, an outsider's view of the television industry,. I'd seen that at the time but it's interesting to revisit given the stuff on early British television that I've been reading (The Intimate Screen and Writing for Television (1955)), about the variety, the diversity, of what gets put on TV - and who decides what gets put there.Coel charts her life growing up on an estate opposite the headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland, one of many striking juxtapositions. There's violence at school, she drops out of college and then ends up writing bits of her life and perspective that get the attention of Channel 4. This leads to her extraordinary Chewing Gum and, after a horrific assault, the even more extraordinary I Will Destroy You. She learns lessons, gets things wrong, and some of her experience is harrowing. Yet, bold, defiantly, she endeavours to be honest, to open things up: her point being that Television will only get its house in order if we can be transparent.

It's an often funny, often very uncomfortable read. Coel is a brilliant writer. An early passage about moths seems to lose its way - but it's a kind of promise, just as when a TV drama opens "cold" on something odd and unclear. It's the writer asking for the trust of the viewer/reader that all will be explained. The final pages, when Coel returns to the moths, will echo in my head for some time.

There's lots here to mull over, not least her call to arms to put the wrong things right: "What part can I play? What can I contribute or say to help?" (p. 98). And I'm struck by her response to the relative imbalance of power between creatives and those in charge.

"I've often been told by people in our industry that many producers, in many companies, 'test the waters' to see what they can get away with. I told them the opposite of what I'd learned in drama school: the only power we have is the power to say 'no'." (p. 64)

I've often heard something like this said in relation to the choices we make as writers about what to write, a recognition of our relative lack of power when producers and commissioning editors are the ones who decide what to green light. All we can do to steer our careers is to decline an invitation when it doesn't feel right, to take a small step backwards.

Coel's version is about stepping forward.

October 19, 2021

Writing for Television, by Sir Basil Bartlett

Following yesterday’s post about The Intimate Screen and British Television up to 1955, I read this short guide to Writing for Television from 1955 written by Sir Basil Bartlett, who is listed on the cover as “Drama Script Supervisor [for the] BBC Television Service”, this credit prefixed on the inside with the word “formerly.”

Following yesterday’s post about The Intimate Screen and British Television up to 1955, I read this short guide to Writing for Television from 1955 written by Sir Basil Bartlett, who is listed on the cover as “Drama Script Supervisor [for the] BBC Television Service”, this credit prefixed on the inside with the word “formerly.”It’s a rather nice little hardback, originally sold for 9s 6d, and “was written at the request of the BBC,” says the blurb on the inside front flap. Although the author “assumes that the reader has already had some experience in writing”, this “severely practical book is for a wider circle than the professional writer only” and will “appeal to the ordinary reader who likes to know how the machinery works”. It was one of a number of practical guides published by George Allen and Unwin, with adverts on the back cover for An Introduction to Journalism by EH Butler and Play Production for Amateurs by Eric Bradwell, and ads inside for Write What You Mean by RW Bell and Technical Literature - Its Preparation and Presentation by GE Williams.

Bartlett provides 76 pages of notes intended, he says, "for the professional writer” (p. 9), and assumes that he (always "he") comes from the theatre. "Basically, Television is a by-product of the theatre," he tells us (p. 11). Indeed, of the up to 90 scripts received by the Drama Department each week, “the majority … are still in stage-play form” (p. 48) rather than being written especially for Television.

“The Drama Department has a dual function. On the one hand it has been for many years a repertory theatre. Week after week it presents to viewers Television versions of outstanding theatre plays by authors of all nationalities and all generations. On the other hand it has a growing and gladly undertaken responsibility for finding new work by new authors and giving it an airing.” (p. 48)There was not a 50/50 split between the two, and Bartlett is also aware of the ratio changing. Of the up to ninety submissions received by the Drama Department each week, “The majority of scripts submitted are still in stage-play form,” (p. 48) but in 1950 the Drama Department produced 105 plays, 95 of them adaptations of established stage plays; in 1954, of a “similar” total, just 30 were established stage plays, the rest either adaptations of new plays, novels or short stories - or, good gracious, “new plays written expressly for the medium” (p. 49). In addition to this, the department produced four serials.

To aid the would-be writer of TV, Bartlett provides extracts from 10 notable TV productions, which - like The Intimate Screen - are evidence of the sophistication and ambition of early TV. For my own reference, they are: The Small Victory by Iain MacCormick (tx 11 June 1954) Return to Living written and produced by Caryl Doncaster (tx 16 February 1954) - The Emperor Jones by Eugene O'Neill and produced by Alvin Rakoff; his first TV play (tx 7 July 1953), The Comedy of Errors adapted as a musical by Lionel Harris and Robert McNab, with music by Julian Slade (tx 20 May 1954) Shout Aloud Salvation by Michael Barry and Charles Terrot - "something of a landmark in Television history [as] it was one of the very earliest attempts to write a full-scale play specially for the medium." Bartlett, p. 101 (tx 15 April 1951)The Bespoke Overcoat by Wolf Mankowitz (tx 17 February 1954)The Disagreeable Man adapted by CE Webber from the novel by Henry Cecil, and "designed to be played entirely with BP [back projection] plates. It was specially chosen to show off Television technique on the occasion of the visit of Her Majesty the Queen to Lime Grove Studios", Bartlett p. 108 (tx 28 October 1953) Episode 4 of The Six Proud Walkers by Donald Wilson (tx 4 August 1954) 1984 by George Orwell, adapted by Nigel Kneale - "A piece of technical virtuosity [and] probably the best script ever written for the Television Drama Department," Bartlett p. 116 (tx 12 December 1954) The Eye of a Gypsy by Lorca, (tx 17 October 1952) Strikingly, Bartlett doesn’t encourage writers to write material expressly for TV. With fees for single performance of an original play at £120, and £60 for a repeat, he admits that “an author … can scarcely make a living out of Television, even if he writes ten plays a year and gets them all accepted" (p. 71) - even if the expansion of television and the development of TV craft may mean increased fees in future. There’s mention of sales abroad, but at this stage he’s talking about selling a script that can then be reproduced, rather than a recording of a BBC-made play.

Instead, Bartlett is entirely pragmatic about using Television to further a career on the stage.

“The BBC Television Service is, however, an excellent try-out theatre. And it is on this basis that it should be considered.” (p. 70)He gives six reasons: “First, he will get his play knocked into shape by experienced script-writers and directors.” Television also affords better casting and production that a small-stage try-out, and the author will get his name known to millions, who might then go see a stage version, and he’ll have the value of newspaper coverage - all while retaining the rights. Elsewhere, Bartlett tells us that - at BBC Television at least - “the standards of the theatre prevail” as “Television respects the author’s integrity”. Indeed, “once an author’s work has been accepted it becomes the sole purpose of the director, actors and technicians to see that it is project as well as is humanly feasible on to the screen.” (pp. 14-15.)

Yet the sense is that the author would have little involvement at all in the televisual elements of screening works primarily conceived for the stage.

“The adaptation of stage plays, old and new, is normally undertaken by BBC staff writers and directors, and outside writers are rarely called in to adapt the work of their playwright colleagues. Most plays, after all, require no more than rigorous pruning, a little transposition of scenes and a general opening up.” (p. 43)Of course, an increased focus on original plays written especially for the screen would obviate this kind of work, and I wonder how much that influenced the decision of Sydney Newman, when he became Head of Drama at the beginning of 1963, to close the Script Department entirely.

That the BBC produced some 105 plays each year helped clarify something for me: why the BBC had a regular run of Sunday-Night and Tuesday-Night plays. It was all down to limited studio space.

“A BBC Television play is rehearsed for either two or three weeks according to its complexity. Most of the rehearsals take place in outside rehearsal rooms, and the cast spends only two days, including transmission day, in the Television studio.” (p. 62)So Studio D at Lime Grove would have Saturday and Sunday booked for the live Sunday-night play; Monday and Tuesday would be for the live Tuesday-night play; Wednesday and Thursday would then be given over to a repeat performance of the Sunday-night play - implicitly, affording it more value than a play shown just once on Tuesday. (As we saw in The Intimate Screen, it was the Thursday-night repeats that got recorded, where examples survive.) The studio was therefore free on a Friday, when a smaller production such as a half-hour serial might be fitted in.

When it began in 1963, Doctor Who was recorded in Studio D on consecutive Friday evenings. This series-of-serials was possible, surely, because by that time, more prestigious dramas were being recorded in the new Television Centre, freeing up space - but the structures and schedules remained.

Then there’s the kind of material suitable for TV. For all Bartlett underlines the connections to theatre rather than film (“Stage plays and Television plays are living things, whereas films are in cans”, p. 14), he has to admit a major difference.

“One of the biggest problems facing the Television writer is that his public is so elusive. [Whereas a playwright can see the audience,] “The Television writer, on the other hand, is writing in a vacuum. He has a potential public of many millions. But he can never be sure, at any given moment, that those millions have not switched off.” (pp. 26-27)Even so, he tells us,

“The viewer is the average man. And what he wants is to be told a story which he can both enjoy and understand.” (p. 27)And he warns that,

“the majority of viewers have no theatrical background. Many of them have never been in a theatre in their lives.” (p. 28 )This was, of course, an insight often ascribed to Sydney Newman but is fundamental to the medium years before he even came to the UK.

So much of the book is about Television as a modern, technological medium but Bartlett’s warnings on subject material firmly place this in history:

"Although not liable to censorship by the Lord Chamberlain it [the BBC] is compelled, by the nature of its Charter, to exercise a strict internal censorship of its own. This amounts to no more than a sense of responsibility for what is shown to the family and seen in the home. Thus there is no place in BBC programmes for plays that might normally be produced in private theatre clubs. And any author who has an urge to write a play on a distasteful theme--rape, for example, or incest or abortion--would be better advised not to write it for Television. ... The BBC must also be cautious about plays with a strong political content. ... In addition, there is a quite natural ban on the portrayal of the Royal Family in fictional programmes.” (p. 18)That said, I held my breath when he raised the issue of writing aimed at minorities - but it wasn’t at all what I expected:

“If he [the author] decides to throw caution to the winds and write deliberately for a minority audience, for the hard core of better-educated viewers, he must remember that the BBC Television Service puts out a single programme and that the time allotted to minorities is considerably less than is possible, for example, on Sound radio, which has three channels. And the competition for the few minority spaces on Television is a stiff one.” (p. 29)It’s a case for accessible, popular television - a grounded, universal TV - very much in Newman’s line.

There’s much more, such as on the popular appeal offered by regular characters and situations in serials and series - though, “With its single programme and shortage of studio space the BBC Television Service cannot embark very frequently on a series.” (p. 42). And there’s a fantastic chapter that takes us through the day of a live recording, explaining everyone’s roles and giving a sense of the tension, and the author getting in everyone’s way, which dovetail’s nicely with the account in Alvin Rakoff’s new memoir.

And then, at the end, Bartlett concludes with something that’s a cognitive leap forward. Though, “People are inclined to be snobbish about Television Drama and to regard it as a slightly disreputable member of the theatrical family” (p. 73), “In the future the theatre will, I believe, have a lot to learn from Television.” (p. 74). He means in doing away with the frame of the stage play - footlights and the proscenium arch - to get up close to, even inside a subject’s head.

“It is an intimate medium and well suited to this task.” (p. 76)As we saw yesterday, he was right - and much sooner than he can have expected. He's a key witness, on the cusp of revolution.

October 18, 2021

The Intimate Screen, by Jason Jacobs

Recommended to me by my friend Dr Una McCormack, The Intimate Screen - Early British Television Drama, published by Oxford in 2000, covers the period 1936 to 1955, and is fascinating.

Recommended to me by my friend Dr Una McCormack, The Intimate Screen - Early British Television Drama, published by Oxford in 2000, covers the period 1936 to 1955, and is fascinating.Jacobs sets out his intention to “revise significantly, rather than refute completely” (p. 3) the model suggested by Gardner and Wyver, that:

“The first phase [of Television drama], primarily under the aegis of the BBC, was one of the last sustained gasps of a paternalistic Reithian project to bring ‘the best of British culture’ to a grateful and eager audience—a mission of middle-class enlightenment. Thus in its early days TV drama picked up the predominant patterns, concerns and style of both repertory theatre and radio drama (as well as many of their personnel, and their distinct training and working practices) and consisted of televised stage plays, ‘faithfully’ and tediously broadcast from the theatre, or reconstructed in the studio, even down to intervals, prosceniums and curtains.” (Gardner C and Wyver J, ‘The Single Play from Reithian Reverence to Cost-Accounting and Censorship’, and ‘The Single Play: An Afterword’, Screen 24/4-5 (1983), cited in Jacobs, p. 3.)Gardner and Wyver were not alone in seeing “a respect for theatre” (Jacobs, p. 7) as “blocking” the liberation of new forms of drama which came in, they felt, for two reasons: with the creation of ITV in 1955 and Sydney Newman starting work in British television in 1958.

“Along came this man with the dream of putting the story of ordinary people and of our times, the contemporary times, on the screen, and doing this with quality, and giving writers freedom to write … This natural force blew through the corridors of television and blew a lot of the cobwebs out. That man probably had a greater influence on the development of television than anyone else.” (Ted Willis, speaking on the 1987 Channel 4 documentary And Now For Your Sunday Night Dramatic Entertainment, cited in Jacobs, p. 7)Jacobs argues that many of the supposed innovations of this “second phase” — a focus on original plays written especially for television, working class subjects, moving the cameras, cutting, location filming etc — had a long pedigree in television already, and that the medium had always aimed at a kind of intimacy with the viewer which set it entirely apart from film, radio and the stage.

As he goes on, that “intimacy” was readily discussed in the press and the BBC’s internal paperwork, and understood in a number of different ways: the intimacy of watching in your own home (rather than dressing up to go out to the theatre), usually on your own or with just a few other members of the household (not a whole theatre audience); the intimacy of softer spoken voices as actors did not need to project to the back of the theatre; the intimacy of live drama, where the audience was witness to events happening in real time (and things might go wrong at any moment); the intimacy of small studio spaces and the close-up…

“Intimacy meant the revelation and display of the character’s inner feelings and emotions, effected by a close-up style of multi-camera studio production.” (p. 8)The sense is that the practicalities of television - in licensing material to put on screen, the limited studio and technical facilities, the smallness of the TV screen, and it being in people’s homes - shaped the kind of drama that was screened, the way it was framed and the audience’s response. The aesthetics of TV drama came from how it was made.

One major issue in exploring all this is that so little TV survives from the first phase: Although recording — and thus retaining — TV programmes wasn’t readily available in the UK until about 1958 (p. 4),

"by 1947 it was technically possible to record television on film so, theoretically, there should be a complete record of programmes from here onwards. Instead, for the pre-1955 period, we have two episodes of The Quatermass Experiment, the 1953 televising of the Coronation, an adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four, a selection of children's programmes from the early 1950s, and some sporting events (Test Match cricket, some football)." (p. 10)Just as in histories of the theatre (and in the sort of Doctor Who archaeology I’m involved in), these missing performances are pieced together from surviving paperwork, recollections and photographs, partial records rather than the full story. Jacobs is excellent at this: each chapter gives the broad context before moving into case studies on particular plays, detailing — as much as is possible — how they were staged and framed.

Some details are fascinating: instantaneous “cutting” from one camera to another was not possible until 1946; until then, “mixing” between two shots could “take up to eight seconds”, requiring great skill on the part of the crew, with some scripts specially written to accommodate the delay (pp. 46-47). There's lots of the limits of what could be achieved, and how small, gradual improvements in technology could change the feel of drama.

In fact, more recordings exist than Jacob suggests: there are surviving bits of pre-recorded material from the 1930s, and the earliest surviving “full” TV drama is It Is Midnight, Dr Schweitzer (tx 22 February 1953) - “full” because the surviving version is the shorter repeat; the original longer version was not recorded. It's striking that all these surviving dramas of the period - Schweitzer, Quatermass and 1984 - were produced by the same person, Rudolph Cartier. As Jacobs details in a 15-page case study on 1984, Cartier was extremely adept and lauded in his time for pushing what TV drama could do — though Jacobs argues that Cartier was selecting from a range of already established techniques rather than originating them entirely. But the retention of Cartier’s work isn't necessarily evidence of him being held in special esteem.

For one thing, other plays were recorded but not retained. The Broken Jug (tx 24 August 1953, produced/directed by Hal Burton) and The 23rd Mission (tx 11 November 1953, produced by Ian Atkins, directed by Julian Amyes) were, says Jacobs, both pre-recorded rather than broadcast live — marked as such in Radio Times, though without any reason being given, annoyingly.

Then there was the issue of copyright. The BBC often had rights to transmit a live adaptation of a theatre play, as an ephemeral performance, but not to retain it in any physical form. In some cases, the corporation was required to destroy recordings, such as a 1939 production of The Scarlet Pimpernel).

"One solution to the copyright problem was to commission original plays for television. The setting up of a script unit in early 1950, and the hiring of Nigel Kneale and Philip Mackie as staff scriptwriters, can be seen as an attempt to generate fresh drama, and drama which could be recorded and owned by the BBC. This would not have been an issue before telerecording when television programmes simply could not be thought of as material commodities [or tradable goods]." (p. 12).The suggestion is that The Quatermass Experiment was selected for recording over other plays of the period because Kneale was on staff and the production was written especially for television. There were still complications: Jacobs also reports issues over the pre-filming of trailers for The Quatermass Experiment because there was no agreement in place with the actors’ union Equity. An agreement was reached, and also a deal whereby only the repeat performance of a play would be recorded, guaranteeing actors two performance fees (p. 113).

Then, in a footnote about the controversy over the political content in 1950 play Party Manners and its repeat being cancelled, Jacobs adds that,

"The BBC were keen to demonstrate that they were not prone to state control, so much so that when similar controversy erupted around Nineteen Eighty-Four the BBC repeated the play in the face of considerable parliamentary criticism. It was the repeat which was telerecorded." (p. 96n)So was Nineteen Eighty-Four recorded — and survives today — because of the controversy?

There's some stuff about the BBC's penchant for "Horror Plays" after the Second World War, perhaps reflecting the mood of the BBC staff — and the nation — who had been in service, but also acknowledging that TV suited the creation of eerie atmospheres and, as a letter to Radio Times in 1948 put it, "actors and actresses like to have 'close-ups' of registered horror" (p. 99).

In his case study on 1984, Jacobs suggests that in expanding what TV could do — using location filming to expand the scale of the story — Cartier turned the intimacy of television on its head. As Cartier himself said, the Michael Anderson film version of 1984 made a year after his own version,

“could not recapture the impact of the TV transmission … It was decidedly different in the TV viewer’s own home, where cold eyes stared from the small screen straight at him, casting into the viewer’s heart the same chill that the characters in the play experienced whenever they heard his voice coming from their ‘watching’ TV screens.” (Cartier, ‘A Foot in Both Camps’, Films and Filming 4/12 (September 1958), p. 10. Cited in Jacobs, p. 138)This was surely reversing the usual, "cosy" intimacy of television to invade the viewer’s home — and the reason the drama proved so effective and shocking. Jacobs cites glowing reviews in the press and the “mostly hostile” letters to the BBC which “criticised the play on the grounds of obscenity”, thought it “‘unsuitable for the vast audience’ or talked about it in terms of ‘pollution’: such productions could be bad for people.” (p. 155)

Jacobs concludes with the fact that Sydney Newman was, in 1956, taken to see the Royal Court's stage production of Look Back in Anger by John Osborne. I’m not sure that date is correct, or that Jacobs is quite right in his analysis here. It’s worth putting this in context.

"In [his work at] the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Newman had witnessed, and had also contributed to, the remarkable flowering of the dramatic arts on television in North America, in which new writers, new actors, and new directors had all played their parts. He also recognised that television was a mass medium of nothing; that because of cultural inequalities most of the audience had little experience of the theatre but much of the cinema; that television drama should reflect and comment on the world familiar mass audience. The story goes that Michael Barry, then head of BBC drama, took Newman to see Osborne's Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court Theatre. That play, with its unusual worm's-eye view of society and its derisive radicalism, seemed to Newman the dazzling light on the road to Damascus; more accurately, it summed up what he had come to believe about drama..." (Bernard Sendall, Independent Television in Britain (1982), cited in Television Drama: An Introduction by David Self, p. 49.)Jacobs thinks it ironic that Newman was taken to the play by Michael Barry of all people, the man whom Newman would replace at the BBC and, “inspired” by the revolution in theatre they had witnessed together, radically overhaul TV drama. (Jacobs also says it was ironic that Look Back in Anger was not particularly successful on stage until an extract was broadcast on television.)

But that surely isn’t quite right. Another Canadian immigrant, Alvin Rakoff, claims in his new memoir that he was offered a job at the Royal Court by Tony Richardson, having both worked together as director-producers at the BBC. Rakoff turned down the offer, "then watched as the Royal Court went on to to revolutionise British theatre when it produced Look Back in Anger." The implication is that Rakoff was offered the job - and the chance to work on developing that play - because of the work he had already done in TV. Indeed, he says the "revolution" in theatre was “started by television writers who were the first to show more interest in ‘the man on the Clapham bus’ than the ladies’ tea party at the vicarage.” (I'm Just the Guy Who Says Action, p. 111).

Fusing that with Jacobs, the implication is that Obsorne's play was riffing on the intimacy, the psychological insight, that was by now characteristic of TV, and intrinsic to the practicalities involved in televising drama. The "second phase" of TV drama ushered in by Newman was not, then, some radical new form but the recognition of strengths and virtues in the now mature TV medium. In that sense, it was more building on what had gone before than breaking from tradition.

October 16, 2021

Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro

Klara and the Sun reminded me chiefly of the Isaac Asimov story, Reason, which so beguiled me as a child. Klara is an AF - or "artificial friend" - an android companion who begins this novel gazing from the window of a trendy shop hoping that someone will buy her. She's an intelligent, observant machine, powered by the light of the Sun, but there's much of the human world she doesn't fully understand and readers must be active participants, filling in gaps in her knowledge or puzzling out what's really happening.

Klara and the Sun reminded me chiefly of the Isaac Asimov story, Reason, which so beguiled me as a child. Klara is an AF - or "artificial friend" - an android companion who begins this novel gazing from the window of a trendy shop hoping that someone will buy her. She's an intelligent, observant machine, powered by the light of the Sun, but there's much of the human world she doesn't fully understand and readers must be active participants, filling in gaps in her knowledge or puzzling out what's really happening.We understand that the small girl who smiles at Klara through the glass shop front and promises to come back and buy her may never return. We understand that a character with a serious illness may never recover. We understand that Klara goes to live with a traumatised, grieving family who don't always behave logically. But we also understand that Klara acts out of genuine concern to do right by these people. All our sympathies are with her, even more so than with the sick child at the heart of the story.

There are some disturbing ideas here: the genetically edited, "lifted" children and the social underclass then left behind; the idea of machine copies of the dead who can live on as comfort to their families; the haunting hints about the cruel treatment inflicted on AFs sold to other families; the understated cruelty of old AFs being left on the scrapheap to succumb to their "slow fade". But really this is an unconventional love story - nominally about two children whose lives are diverging, and actually about the devotion shown to them by their keen-to-please servant.

Then there's Klara's relationship with the Sun, her power source, who she assumes can power others, too - and is sentient and listening. I'm not sure how I feel about the ending of the book, which implies Klara might be right, that the Sun can intervene. It feels dissatisfying because, for once, there's no alternative to the meaning Klara applies here - there's no potential alternative reading that we can infer, other than lucky coincidence.

The coda, with a figure from Klara's past returning for one last conversation, is much better handled - poignant, sad, and with Klara still trying to make sense of human behaviour and her own complex feelings.

October 14, 2021

Doctor Who Magazine #570

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine has lots on the imminent new TV series with lots of exclusive access to cast and crew.

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine has lots on the imminent new TV series with lots of exclusive access to cast and crew.There's also bits from me. Deputy editor Peter Ware read my post here about Alvin Rakoff's new memoir and asked me to interview him about it. There's another Sufficient Data infographic, illustrated by Ben Morris and this time tracking the Sixth Doctor's efforts to pilot the TARDIS to particular destinations. And I get a name-check in the nice review of the new Blu-ray release of The Evil of the Daleks.

ETA Alan Barnes' feature on the episode Blink also cites my 2017 interview with writer Steven Moffat.

October 4, 2021

Big Sky, by Kate Atkinson

I've been gadding about this week, braving the petrol crisis to venture to Cambridge and Liverpool, accompanied on the road by Jason Isaacs reading Big Sky - the fifth and, to date, final Jackson Brodie novel. Isaacs is perfect for this: he played Brodie in the TV series and - unlike readers of previous books in the series - knows how to pronounce words such as "Niamh". He's also good at making various characters distinct, which is important in a novel that depends on the interlinking relationships of a whole crowd of different, well drawn people.

I've been gadding about this week, braving the petrol crisis to venture to Cambridge and Liverpool, accompanied on the road by Jason Isaacs reading Big Sky - the fifth and, to date, final Jackson Brodie novel. Isaacs is perfect for this: he played Brodie in the TV series and - unlike readers of previous books in the series - knows how to pronounce words such as "Niamh". He's also good at making various characters distinct, which is important in a novel that depends on the interlinking relationships of a whole crowd of different, well drawn people.In the years since Started Early, Took My Dog , time has moved on and yet little has changed for Jackson Brodie. He's still a private investigator, still haunted by the murder of his sister which compels his efforts to find and save other missing women. And yet his caseload is all sweating small stuff: following a married man and his girlfriend on dates; doing background research on some people; running round after his ex and their now-teenage son.

Lots of it involves people we've met before: that ex, Julia, is from the first book and she's been a constant presence. There's the return of Reggie Chase from book three, now working in the police but denying that's down to Jackson. We call back to events and people from previous adventures, because part of the thing is that Jackson lives in the past, but also trauma lasts for a lifetime. In addition, there's a more meta textual thing going on. Julia plays a pathologist in a TV series about a police detective, and at one point a cast member asking Jackson's advice for a scene. Then there's Jackson's continued reference to his own "little grey cells", linking him to Poirot (just as, a few sentences before introducing us to Poirot, Agatha Christie mentioned Sherlock Holmes). It's Jackson, and this whole endeavour, as part of a continuum, of death as entertainment.

To be honest, death takes quite a time to put in an appearance. Nothing much happens for a good few hours of the audiobook - we trail after Jackson and other characters going about their various lives, some of which intersect. But there are hints of something darker under the surface and as we pick over details, Jackson's instincts are shown to be absolutely, horribly right. There are a lot of women in danger...

I found the first half of the book mostly fun if a little too on the nose - anyone in favour of Brexit is crass and a bit (or a lot) racist, and there's lots of Jackson being grumpy about modern life. A running gag is that we get a character's train of thought and then someone else telling them to get a move on or to focus on matters at hand, as if the characters are sniping at their author's flights of fancy. As I said of the previous novel, this kind of thing can all feel a bit self-indulgent. But I think it's works better in this case, not least because this groundwork binds us to the various characters before the plot kicks into gear and things get properly thrilling and tense.

What follows is often brutal - children in danger, some horrible deaths, and a seemingly endemic violence against women and girls. Atkinson has lots to say on the subject, but woven through the novel and from various perspectives so it never feels like a lecture. It is harrowing and compelling.

That makes it sound like an angry novel, and it is in places. Yet it's also often funny, and the over-riding emotion is melancholy - for lives lost and blighted, for the harm done by callousness and greed, for the long shadow it all casts over everything.

In that, and in its thrilling tension and it feeling like it had something to say, it chimed with No Time To Die, which I went to see on Saturday and really liked - but want to see again before committing my little grey cells.

September 23, 2021

The Dalek Factor

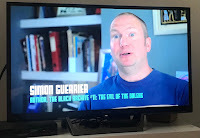

Out on Blu-ray and DVD this week is the new animation recreating

The Evil of the Daleks

, a seven-episode Doctor Who story from 1967 of which only episode 2 still survives. The wealth of extras include making-of documentary The Dalek Factor produced by Steve Broster. It includes me rabbiting on a bit wild-eyed and excited to be talking to anyone outside my immediate family.

Out on Blu-ray and DVD this week is the new animation recreating

The Evil of the Daleks

, a seven-episode Doctor Who story from 1967 of which only episode 2 still survives. The wealth of extras include making-of documentary The Dalek Factor produced by Steve Broster. It includes me rabbiting on a bit wild-eyed and excited to be talking to anyone outside my immediate family.As the caption says, I wrote a book about The Evil of the Daleks for the Black Archive series, which is still available and rather good.

September 17, 2021

Doctor Who Magazine #569

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine includes two things by me.

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine includes two things by me.First, the ingenious Gavin Rymill and Rhys Williams have reconstructed in CGI another studio floor plan from a missing episode of the series, this time the first part of The Macra Terror (1967). Rhys and I have written the accompanying words, trying to make sense of exactly how the story was realised with so little money, time and space.

Then, the latest instalment of Sufficient Data tackles the important subject of what, exactly, the Second Doctor keeps in his capacious pockets and when we first see each item. As always, the infographic is by Ben Morris but this time I shared the exhaustive research with Andrew Ledger, who undertook the extraordinary feat of rewatching every extant Troughton episode to be sure we hadn't missed anything.

September 10, 2021

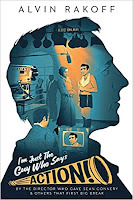

I’m Just the Guy Who Says Action, by Alvin Rakoff

At the end of this fascinating, moving memoir, the TV and film director Alvin Rakoff recalls a final conversation with his dying wife, the actress Jacqueline Hill. She wanted him to tell her about the holidays they’d enjoyed, such as exploring Spain and Portugal in a dilapidated old car.

At the end of this fascinating, moving memoir, the TV and film director Alvin Rakoff recalls a final conversation with his dying wife, the actress Jacqueline Hill. She wanted him to tell her about the holidays they’d enjoyed, such as exploring Spain and Portugal in a dilapidated old car.

“The past, as I said, is a sunshine memory. I ranted on. Embellishing certain characters, exaggerating minor problems, emphasising funny moments, trying hard to remain focused on storytelling.” (p. 170)

The implication, surely, is that much of the rest of the book has been gilded. And yet the thing that strikes me is how packed it is with telling, honest detail. It’s largely about the production of a live TV drama, Requiem For A Heavyweight, in 1957, and Rakoff giving Sean Connery his first leading role (with a small role for Michael Caine, too). The play, he says, is now lost to the ether: a scratchy audio recording of most of it survives, as well as some photographs and the camera script full of Rakoff’s notes on how it should be staged and framed. YouTube also has the original, US version - directed by Ralph Nelson and with Jack Palance in the lead role.

But the book is less an effort to recreate the lost production as to share a vivid sense of the thrill and terror of making it, what it cost Rakoff and his leading lady and then-girlfriend Hill emotionally, and - for all its success - the uncertain time that followed. How extraordinary the commissioning process seems today. Roughly every eight weeks, Rakoff would be summoned to see Michael Barry, “HDTel” or Head of Drama for the BBC’s sole TV station. Even the description of Barry’s office is striking:

“Curtains forever drawn. One dim bulb from a desk lamp, the only source of light. Presumably so he could more readily monitor the output from the nearby studios, relayed through the dark-wooded set in the corner. He himself wore his customary alpaca jacket over armband-hitched shirt sleeves. Complete, of course, with a tie.” (p. 151)

“He would give me a broadcast date. Nothing more. And as I would leave his office he always added, ‘A comedy would be good. A comedy would fit well into the schedule. See if you can find a comedy.’ Neither I nor any of his other subordinates managed to find many comedies. I would go away. Find a play. Buy it. Print it. Cast it. Involve a designer. Consult make-up, hair, wardrobe. Rehearse. Work out a camera script. … Then into the studios for broadcast. Live. Collapse with crew and cast for a few drinks after the show. The next day I would be back in Michael’s office and he would praise what I had done - usually - or tell me - a rarity - if he hadn’t liked it. … The meeting would again end with him telling me the date of my next commitment. And as I got to the door, the inevitable phrase came, ‘See if you can find a comedy.’ The routine was cyclical.” (p. 34)

Then, after Requiem, when Rakoff is too exhausted to commit immediately to the next production, Barry treats it as betrayal and pretty much casts him adrift - at least, for a time. Rakoff picks up with the noted film producer Michael Balcon, who seems to wield just as extraordinary power and hold just as powerful grudges.

There are plenty of insights into the mechanics of making TV at the time - the cameras, the politics, the personalities to be juggled, the impact of that work. For example, he notes how Look Back in Anger revolutionised British theatre when it was first staged by the Royal Court in 1956.

“A revolution, incidentally, started by television writers who were the first to show more interest in ‘the man on the Clapham bus’ than the ladies’ tea party at the vicarage.” (p. 111)

We follow the production of Requiem through casting and rehearsals, into Studio D at Lime Grove Studios, where there was so little space that one set had to be constructed around the moving actors as the play was broadcast live. Tension mounts as rehearsal after rehearsal fails to get this trick shot right, just one of a hundred stresses to contend with - the account of the live performance makes exhilarating reading. But it’s the details that make it so vivid: the etiquette of getting rounds in for the crew in the British Prince pub down the road, or of Connery bringing his then girlfriend to sit in on rehearsals, of Rakoff and Hill keeping emotionally distant while working together, of the crisis in their relationship.

It’s often very honest - about their sex life and about other people’s bad behaviour - and there’s an edge to some of the humour, Rakoff and Hill finding a couple of incidents comic that I felt more disturbing. But then perhaps that’s the gilding. When Rakoff is comforting his very ill wife with tales of that perfect 11-week holiday in 1960, she makes a typically insightful remark.

“Only poor people can afford [such] long holidays … Nobody wanted us back here.” (p. 170.)

See also:

Alvin Rakoff interviewed about the book on The Film Programme, August 2021Jaqueline Hill: A Life in Pictures, the short documentary by me and Thomas Guerrier, in which we spoke to Rakoff at his home, is included on the 2011 DVD of Doctor Who story Meglos and the more recent Season 18 Collection.Jaqueline Hill: A Future in Five Minutes, a biography by my friend Louise BremnerMe on Sean Connery’s film roles in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970sSeptember 9, 2021

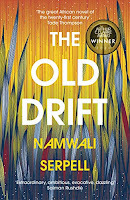

The Old Drift, by Namwali Serpell

The winner of the 2020 Clarke Award for best science-fiction novel of the year is a sprawling epic, charting the lives of multiple generations in Kalingalinga, Zambia, from the arrival of British coloniser Percy M Clark on 8 May 1903.

The winner of the 2020 Clarke Award for best science-fiction novel of the year is a sprawling epic, charting the lives of multiple generations in Kalingalinga, Zambia, from the arrival of British coloniser Percy M Clark on 8 May 1903."I set out for the drift five miles above the [Victoria] Falls, the port of entry into North-western Rhodesia. The Zambesi is at its deepest and narrowest here for hundreds of miles, so it's the handiest spot for 'drifting' a body across. At first it was called Sekute's Drift after a chief of the Leya. Then it was Clarke's Drift, after the first white settler, whom I soon met. No one knows when it became The Old Drift." (p. 4)We follow the course of this settlement to some time in our own future, the world transformed by technology, the [HIV] Virus and [climate] Change.

For much of its 563 pages I was wondering how it qualified as science-fiction. There's an element of fantasy in the life of Sibilla (born 1939), the Italian girl-woman-grandmother who's entire body and face are covered in thick, fast-growing hair; Agnes (born 1943) plays tennis despite being blind; Matha (born 1948) weeps without stopping for decades, her eyelashes knitting together. Before that stage of her life, there's something delightful about the period in the mid-60s where Matha is an afronaut in the Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy, whose revolutionary aim is to beat the super-powers to the Moon.

"The ten-foot copper cylinder was propped on its end in the grass, listing peaceably, its bottom quarter singed black from pre-launch testing. The take-off had been disappointing from the point of view of spectacle - Cyclops I had only risen six feet before it crashed to the ground. The mukwa wood catapult he had been considering would not be powerful enough; the mulolo system, while ideal for training cadets to withstand weightlessness, would never swing far enough. Turbulent propulsion was the only way forward!" (p. 162)It's an often very funny book, full of rascal characters dodging their way through life. In many cases they have little choice if they are to survive. Existence here is often brutal, with sudden, shocking moments of violence and loss and betrayal. Each chapter focuses on a different character's perspective, and we know from the family tree at the start that they - or their descendants - are to intertwine. There's a lot of mixture: of race and culture, of research and technology into people's everyday lives, of history seeping into present such as the effect that an old recording can have on succeeding generations.

In the last section of the book, we veer into more hard sf territory, with the populace encouraged to have "Beads" implanted in their hands, which give them access to the internet and an in-built torchlight, but also puts them at the mercy of their government and foreign pharmaceutical powers, and have racial / colonial undertones. Threads that have woven through much of the story come together: racism, technology, revolutionary politics, the ways we mark and amend our bodies with haircuts, tattoos, implants...

An earlier winner of the Clarke Award, Bold as Love by Gwyneth Jones, annoyed me because its benign political future was, I felt, so lacking in detail - as if all that is required to create a utopia is well-meaning people in charge. The Old Drift offers a more complex, nuanced view full of unintended consequences and a sense of greater context - the lives of the people of Zambia affected by its history with Europe, present dealings with America and China, and an uncertain global future given dramatic changes in climate. The last pages, where a revolution kind of happens by accident, is exciting and scary and sci-fi, yet credible - I think because it embraces that chaos, the complexity of the mix, the uncertainty of outcome.

A brief coda then drops some bombshells. The voice who has spoken between each chapter is not what they seemed but - fittingly - something more complex and mixed-up. They tell us, abruptly, of the sudden death of one of the main characters, and of a son born into a new, uncertain world very different from all we've witnessed so far, we hope but not necessarily better. There's no sense of what his life might entail, just that life will, somehow, continue, all of this part of a far bigger picture, as we all slowly drift among the stars.

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers