Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 35

November 20, 2021

Gallifrey's Most Wanted - Runcible Report #24

I'm a guest on the Gallifrey's Most Wanted podcast, chiefly chatting to hosts Jeff and Ross about the trilogy of Doctor Who stories I wrote starring Peter Purves and Tom Allen. But there's also some stuff about my new Sherlock Holmes novel The Great War and much more besides. You can listen to the podcast here:Gallifrey's Most Wanted - Runcible Report #24: Simon Guerrier

I'm a guest on the Gallifrey's Most Wanted podcast, chiefly chatting to hosts Jeff and Ross about the trilogy of Doctor Who stories I wrote starring Peter Purves and Tom Allen. But there's also some stuff about my new Sherlock Holmes novel The Great War and much more besides. You can listen to the podcast here:Gallifrey's Most Wanted - Runcible Report #24: Simon Guerrier

November 14, 2021

In Search of HV Morton, by Michael Bartholomew

This is a very good biography of a very successful writer and pretty awful human being. Michael Bartholomew brilliantly teases out the real man from the literary persona, effectively providing biographies of two people: the real Harry Morton and the invented HV.

This is a very good biography of a very successful writer and pretty awful human being. Michael Bartholomew brilliantly teases out the real man from the literary persona, effectively providing biographies of two people: the real Harry Morton and the invented HV.Morton's most famous work is In Search of England (1927), in which he escaped London for excursions in a bull-nosed Morris. Bartholomew makes the point that the title suggests this England had become hidden or lost and so had to be sought through its countryside and history. He goes on that this struck a chord in nation still reeling from war. He also points out that the final destination in the book, a village in which Morton finds this England, is almost certainly a fiction. As he says, there's a subtle but important difference between a myth and a lie... I'll return to this when I reread In Search of England.

Bartholomew is aided by a wealth of evidence which any researcher would envy (me included). HV Morton published more than 40 books, almost all of them non-fiction, often recounting his adventures with wry, self-deprecating insight. Many of the books were collections of reports for newspapers (and, later in life, features for glossy magazines), with telling differences between what was originally printed and what was then revised. That would be quite enough, but Bartholomew also had access to a 200-page unpublished autobiography written in Morton's last years and a collection of diaries and correspondence ranging right back to his earliest days. This means the biographer is able to compare a diary account of a formative experience with how Morton chose to remember it half-century later, and then contrast this with the version put in print. There is even a dated list of Morton's sexual conquests, totalling some 100 different individuals, with "wh" marking those that he paid for, which Bartholomew matches against the other details in his timeline.

There are plenty of gaps in the record - missing diaries, absences in what Morton tells us - and Bartholomew is good at deducing connections, motives, feelings. He also tells us when it's his own speculation by adding "I think", as well as saying when nothing firm can be said. Literary biographies can all too often be an annotated list of published works, reductively pinning down real events that inspired the writer, as if writing is little more than copy and paste. Bartholomew achieves something very different - and better. Morton is more than simply a witness: we come to understand the creative act, even in non-fiction. There is careful research beforehand, skilled observation at the time, a period of reflection to put things in perspective, and then craft in the actual process writing - from moulding loose events into a story, to the striking turns of phrase, the well-chosen idiom or analogy, and the deftly worked light humour.

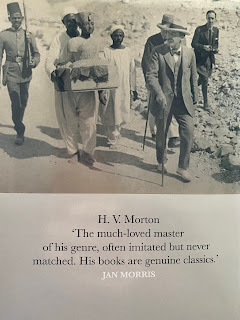

A good example of this use of different sources is what Bartholomew can tell us about a particular photograph, chosen for the back of the dust jacket:

The photograph is also included in the plate section of the book, with the following caption:

"The opening of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1923 -- Morton's first big break as a reporter. The photograph was taken by the Times photographer. Under armed escort, treasures are being removed from the tomb. The figure leading the way is the official archaeologist, Howard Carter. The figure on the extreme right, furtively shadowing the party and taking surreptitious photographs, is Morton. When the photograph was published in The Times, Morton, the interloper, was cropped from the image."

The next plate is the front page of the Daily Express for 17 February 1923, with Morton's coverage - "Pharaoh's Coffin Found" - the first headline. Bartholomew follows the thread of Morton's early passion for archaeology and friendship with antiquarian GF Lawrence, how this helped him get the Tutankhamun gig (the Express determined not to let the Times have a monopoly on the story), the effect this trip had on Morton and how it all tied in to the historical perspectives in his later books.

It's interesting to read that, while waiting to be sent out to fight in the war, Morton was stationed in Colchester and involved in some excavations of Roman finds there. This was also true of the archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. There's no mention of Wheeler in this book, or of Morton in Jacquetta Hawkes' biography of Wheeler, and perhaps they never overlapped in life. Yet it strikes me that these womanising rogues had a lot in common, and Wheeler had a similar way of making direct connections to the ancient past. During excavation of Maiden Castle in the 1930s, Wheeler's brilliant deductions about the stages of a Roman siege were informed by his own battlefield experience in the war. Yet I wonder if the two men would have been at cross purposes: Wheeler using modern experience to unpick the truth of history, Morton looking to the past to provide a modern fiction... I'll keep an eye out for references to Wheeler in Morton's books.

Bartholomew has an eye for wry humour, such as when he details a break-in at the office young Morton was renting with a friend so that Morton could write a novel and the friend a play.

"The project petered out, before Morton had completed chapter one, when a burglar broke in and made off with the kettle, tea and biscuits, but disdained to steal the manuscripts." (p. 82)

We also quickly get a sense of Morton's character, his presence in any room. While I envy Bartholomew his wealth of evidence, I wonder how much he enjoyed the time spent with his subject. Morton's insecurities and womanising are exhausting from the off but the racism creeps up on the reader. True, his travel writing is full of caricatures - there are often salt-of-the-earth yokels or idiot Americans for his narrator to converse with - but Bartholomew is good at showing how often Morton plays against easy stereotypes and presents a more complex view... at least in his published writing. In private, he's often shockingly racist, continually sympathising with the Nazis during the war and then emigrating to South Africa just as the apartheid regime came in.

Bartholomew confronts this head on and at some length:

"For him to to have persisted with a rosy view of fascism, long after others had seen the light, indicates more than naivety." (p. 172)

He also points out the contradictions in Morton's prejudice: this man who made his name celebrating England actually despised much of its people and ways of doing things. Morton sympathised with and admired the Nazis and assumed they'd win the war, and yet was also a dedicated leader of a Home Guard unit, expecting to die with his men in token, doomed resistance to the inevitable invasion.

There are other ironies, such as - "improbably", as Bartholomew says - when the Labour Party published a pamphlet by Morton, What I Saw in the Slums (1933), with a foreword by party leader George Lansbury. Bartholomew makes the case that George Orwell surely read this ahead of his own, better known, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), and even argues that of the two, Morton is the more sensitive and egalitarian.

"Morton's own descriptions of women are just as powerful [as Orwell's], and are less patronising. He writes, for example, of women who strive to put a symbolic barrier between their home and the even more squalid street beyond, by whitening the doorstep: 'Thousands of horrid doorsteps, worn as thin as wafers in the centre, are whitened or raddled. Every time a door opens you see a woman cleaning something.' What I Saw in the Slums is an impressive little book." (p. 147)

Bartholomew is no less impressive. There's lots that's uncomfortable in Morton's life - or parallel lives - but the story is well told. Note to self: this is how it's done.

November 13, 2021

Doctor Who Magazine #571

The latest Doctor Who Magazine is, of course, devoted to the new TV series will lots of exclusive access to cast and crew.

The latest Doctor Who Magazine is, of course, devoted to the new TV series will lots of exclusive access to cast and crew.There's also another Sufficient Data infographic from me and illustrator Ben Morris, this time on all the times the Doctor has used the alias "John Smith", or had it applied. Ben is also one of the contributors profiled on page 3.

November 12, 2021

Cinema Limbo: The Wicker Man (2006)

Jeremy Phillips and I discuss the merits - if there are any - of the 2006 remake of The Wicker Man on the latest episode of the Cinema Limbo podcast.

Jeremy Phillips and I discuss the merits - if there are any - of the 2006 remake of The Wicker Man on the latest episode of the Cinema Limbo podcast.You can also hear me on past episodes:Cinema Limbo: Smoke (1995)Cinema Limbo: King Kong (1976)Cinema Limbo: Ryan's Daughter (1970)Cinema Limbo: Highlander II - The Quickening (1991)

November 11, 2021

The Secret Barrister

It's taken a while to get through this because it's both dense and pretty grim. The anonymous author makes a compelling case about the failings of the judicial system and what and who is to blame. I worked in the House of Lords for 13 years and followed the passage of lots of legislation, so knew of some of the issues detailed here, yet much still came as a shock.

It's taken a while to get through this because it's both dense and pretty grim. The anonymous author makes a compelling case about the failings of the judicial system and what and who is to blame. I worked in the House of Lords for 13 years and followed the passage of lots of legislation, so knew of some of the issues detailed here, yet much still came as a shock.At its best, I think, the Lords could spot potential unintended consequences of proposed new law. Often, an elderly noble and learned figure would rise unsteadily to share some anecdote about a case they were involved in maybe 40 years before. They had learned from those mistakes, and hoped to spare some further unfortunate from a repeated injustice. It's a particularly insidious trick, then, to smuggle significant changes into secondary legislation where there's less chance of teasing out detail.

"The practical consequence of reforms snuck onto the statute book by stealth in 2012 is to financially punish innocent people for the 'crime' of being wrongly accused. When I explain this to non-lawyers, they assume I'm joking, or exaggerating for effect." (p. 199)

The issue here is the decimation of legal aid, the impact being what the author calls an "Innocence Tax", and entirely premised on a false narrative that spiralling costs were all the fault of the lawyers.

"In 2007, the House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Committee heard evidence that the significant rises in Crown Court legal aid costs was largely down to increase in volume of cases, propelled by the creation of more criminal offences, and concluded that 'the average cost per claim did not and has not significantly increased'. Legal aid had therefore increased not because of fat-cat lawyers exponentially milking the taxpayer, but because the state was increasing the volume of cases." (p. 208)

Too often, Governments boast that they will bring about "change", a word that is not the same as "improvement". The result is ever more tinkering, meddling, chaos.

"To try to make sense of sentencing is to roam directionless in the expansive dumping ground of the criminal law. Statutes are piled atop statutes. Secondary legislation bearing titles unrelated to the amendments they make to primary legislation and the half-baked, half-enacted and half-revoked brainchildren of some of our dimmest politicians lie strewn across the landscape, stretching out farther than the eye can see. The many hundreds of legislative provisions exceed, at a conservative estimate, 1,300 pages. If one were seeking a totem to the despair caused by the work of licentious, headline-chasing governments revelling in the ruin they wreak, sentencing law would be it." (p. 286)

We've seen it over the past few weeks: the rush to respond to some incident by bringing in new legislation, rather than ensuring that current legislation has been adequately applied - which more often than not equates to whether it's being adequately resourced. That's the theme here: the awful cost inflicted by ill-thought attempts to save money.

The grimmest thing is that, like The Blunders of Our Governments, it paints a pretty bleak picture of systematic failure - which has only got worse since publication.

November 2, 2021

Out now: Sherlock Holmes - The Great War

Published in the UK today by Titan Books (and in the US on the 16th), Sherlock Holmes - The Great War is my first novel in a while. The blurb goes like this:

Published in the UK today by Titan Books (and in the US on the 16th), Sherlock Holmes - The Great War is my first novel in a while. The blurb goes like this:December 1917. An important visitor arrives at a field hospital not far from the front, who makes sharp deductions about the way the ward is run based on small details that he sees. Sherlock Holmes is apparently only present for a tour, but asks searching questions about a young officer who apparently died in the hospital, but whose records have mysteriously vanished. As Holmes digs deeper, details emerge pertaining to a cover-up that stretches from the trenches to the top of the War Office, and conspiracy on both the British and enemy fronts.

On Sunday, I was a guest on the live Writeopolis! podcast and talked a bit about the book, and the Jeremy Brett version of Doyle's "The Man with the Twisted Lip".

October 30, 2021

The Bookshop, by Penelope Fitzgerald

With a bit of driving to do, I downloaded the audio version of The Bookshop read by Eve Karpf. It is, as Backlisted led me to expect, a quietly devastating novel about Florence Green's efforts to run a bookshop in a small town. There's the same eye for telling detail as in the two previous Fitzgerald novels I've read (Offshore and

The Gate of Angels

), the same mix of comic and melancholy. It's a book full or wry irony, too, such as old, kind Mr Brundish's view on whether the locals will cope with reading Lolita:

With a bit of driving to do, I downloaded the audio version of The Bookshop read by Eve Karpf. It is, as Backlisted led me to expect, a quietly devastating novel about Florence Green's efforts to run a bookshop in a small town. There's the same eye for telling detail as in the two previous Fitzgerald novels I've read (Offshore and

The Gate of Angels

), the same mix of comic and melancholy. It's a book full or wry irony, too, such as old, kind Mr Brundish's view on whether the locals will cope with reading Lolita:"They won’t understand it, but that is all to the good. Understanding makes the mind lazy." (p. 101)What makes The Bookshop different from the other Fitzgerald novels I've read is its implacable villain, Mrs Violet Gamart, who - all for the very best reasons, she tells herself - sets out to destroy Florence and her dream. She's an extraordinary character: initially a figure of fun, then ever more monstrous. It's a while since a fictional character made me angry.

Gamart apparently owes something to Sophie Gamard in Balzac's in Le Curé de Tours (1832), and she exemplifies a cynical line in The Bookshop about life being made up of "exterminators" and "exterminatees". While the bookshop is assailed by the elements (damp, seasonal flooding, subsidence), Florence is harassed by purposeful action.Gamart has a powerful network of accomplices - a cowardly lawyer, a nephew who is an MP, a feckless chap from the BBC - to make a number of spurious legal claims against Florence, even changing the law to force through her own way.

This particularly struck a chord because, by chance, I'm also reading The Secret Barrister.

"Geoffrey Robertson QC offered a withering description of magistrates in his evidence to the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee in 1995, painting them as:

Ladies and gentlemen bountiful, politically imbalanced, unrepresentative of ethnic minority groups and women, who slow down the system and cost a fortune.

In fairness, we have seen slight improvements since 1995, a time when JPs were recruited sans interview by a tap on the shoulder from an old chum. But the unsurprising legacy of an institution which, until 1906, jealously restricted membership to the landed gentry, and until the 1990s was still dominated by freemasons, is that today with your average bench, you're not entrusting your liberty to the collective wisdom of twelve everymen; the butcher, baker, candle-stick emporium televangelist etc. You're often pitching to the admissions board of a 1980s country club." (The Secret Barrister, p. 58)

PS: In case it's of interest, last year I wrote a Doctor Who story set in The Bookshop at the End of the World.

October 28, 2021

The Gate of Angels, by Penelope Fitzgerald

Fred Fairly has a Junior Fellowship at the College of St Angelicus, Cambridge, in 1912. It's a good, respectable job that seems to set him up for life, but for an important proviso. By long-standing custom, no women are allowed on the site - nor even female animals if they are able to produce offspring. Basically, Fred is prohibited from having a serious girlfriend, let alone a wife. Which is fine until his nasty bicycle crash with Daisy Saunders, with whom he almost immediately finds himself in love...

Fred Fairly has a Junior Fellowship at the College of St Angelicus, Cambridge, in 1912. It's a good, respectable job that seems to set him up for life, but for an important proviso. By long-standing custom, no women are allowed on the site - nor even female animals if they are able to produce offspring. Basically, Fred is prohibited from having a serious girlfriend, let alone a wife. Which is fine until his nasty bicycle crash with Daisy Saunders, with whom he almost immediately finds himself in love...The Gate of Angels is full of the same light touch with darkness under the surface as the author's Booker-winning Offshore. It strikes me that both books are focused on misfits, living in the cracks between the "normal" or "established". The episode of the Backlisted podcast devoted to Fitzgerald's Human Voices (which I've yet to read) compares Fitzgerald to Nancy Mitford in observing eccentricity and foible - but with the important difference that Fitzgerald is more often kind in what she observes. These are ridiculous people, but our sympathies are with them.

Which real-life characters were closely observed in this instance? Fred's predicament struck a chord, as mathematician John Edensor Littlewood (1885-1977) could not marry the woman he loved without foregoing his place at Trinity; the result being that my great-grandmother married someone else (but, er, continued to see "Uncle John" all the same). I wonder, now, how common such arrangements might have been.

Some of the darkness of the novel stems from our own knowledge of the future: that there is a war around the corner, and that the arguments detailed here about the nature of the atom will produce spectacular results and entirely change the world. Yet there's more to it than that. For all the book pokes fun at the all-male academics - the one who writes ghost stories in the manner of MR James, or the hanger-on who rather logically concludes that he might take on Fred's girlfriend for himself - there's a constant, disquieting threat, especially to women.

One sequence particularly struck me. There's an extraordinary description of 150,000 south Londoners commuting each morning, the journey,

"compared at that time by sociological observers to a great war or catastrophe in a neighbouring land from which the fugitives, forbidden to look back, scurried over the river bridges by any means available to them, only checked by the fear of falling underfoot." (p. 76)

Daisy, aged 15 (in flashback), is caught up in this maelstrom, one that is predatorily male, such as when she's on the tram:

"Those who did the approaching, in the stifling proximity of the tram, were inclined not to believe in the wedding ring [she wore as protection], and knew what else Daisy was wearing as well as she did. It was a battle with no accepted rules and when the tram began to roll with its plunging, strong-smelling human freight, men put their hands over their ticket and money pockets while schoolboys protected their genitals and women every point of contact, fore and aft." (p. 77)

At 19, Daisy's efforts to help a suicidal man only get herself into hot water, and we well understand her predicament - unemployed, orphaned and poor - when a decidedly unpleasant character suggests taking her to a hotel. We also understand, when this has been such constant background noise in Daisy's life, why she now doesn't quite say no, for all this will spell disaster.

The result is that we really feel for her and for Fred and this rash decision casts a pall over their chances of happiness together. Brilliantly, really brilliantly, we're not told how things end up with Fred and Daisy, and things seem quite impossible for them until the last line of the book. It's so lightly done; it's so powerfully effective - a good summary of the book as a whole.

October 25, 2021

Offshore, by Penelope Fitzgerald

A few days ago, my knowledgeable friend John Williams tweeted that,

A few days ago, my knowledgeable friend John Williams tweeted that, "Penelope Fitzgerald was treated abominably by parts of the literary establishment for daring to win the Booker Prize for Offshore in 1979 ... she was on The Book Programme afterwards where that dreadful arsehole (and host) Robert Robinson introduced the show by saying that 'the wrong book had won' and encouraged the other guests to tell Fitzgerald what they thought about her winning incorrectly."

Appalled by this, I sought out a copy of Offshore (and also The Gate of Angels, which the Dr recommended). It's a brilliant, short novel about bohemian misfits living on houseboats in Battersea circa 1961 - Alan Hollinghurst says in his introduction that clues in the text to the exact date are a little contradictory. These are liminal people living liminal lives:

"You know very well that we're two of the same kind, Nenna. It's right for us to live where we do, between land and water. You, my dear, you're half in love with your husband, then there's Martha who's half a child and half a girl, Richard who can't give up being half in the Navy, Willis who's half an artist and half a longshoreman, a cat who's half alive and half dead..." (p. 54)

One objection to it winning serious literary prizes may be that it's often funny. An early example has single mother Nenna visit the married couple on the next boat:

"Laura sat down rather heavily.

'How does it feel like to live without your husband?' she asked, handing Nenna a large glass of gin. 'I've often wondered.'

'Perhaps you'd like to fetch some more ice,' [her husband] Richard said. There was plenty.

'He hasn't left me, you know. We just don't happen to be together at the moment.'

'That's for you to say, but what I want to know is, how do you get on without him? Cold nights, of course, don't mind Richard, it's a compliment to him if you think about it.'"(p. 12)

It's the sort of thing, I thought, you might get in Reggie Perrin. Like that, the comedy here masks a lot of melancholic stuff. There are those who can't abide a life on the river, and those who adore such existence but for whom it cannot last. From the local teachers and priest, to the peculiar school friend of Nenna's estranged husband, there is constant pressure to conform with "normal" life on land and be as miserable as everyone else. Then there are the dangers of this kind of life: the threat of falling in to the water, or a boat succumbing to leaks, even the risk of violence...

It's all very neatly observed, the author basing it on her own experience (as she did with many of her novels), but changing things to give one particular real person a less tragic fictional end. Perhaps Offshore was dismissed because of this lightness of touch, but it's also a very smart book, threaded with knowledge and insight. There is lots on the practicalities of such an existence, of the shifting tides, the feel of the water. Nenna's daughters shrewdly spot tiles made by William de Morgan while out mudlarking, and know his life and work enough to correctly judge their value; they strike a hard bargain with the owner of an antique shop who makes the mistake of assuming their ignorance. (We then see the true value of the tiles: the girls earn enough money to splash out on records by Cliff Richard.)

On another occasion, one of the girls tours the Tate, remarking on what Whistler and his contemporaries did and didn't get right in their portraits of the Thames - the behaviour of the water, the behaviour of gulls.

"The attendant watched her, hoping that she would get a little closer to the picture, so that he could relieve the boredom of his long day by telling her to stand back." (p. 59)

It's another example of the knowledge, the skill, of these women being overlooked. But also there's something like Whistler in this novel as a whole: a portrait of the people on the river, a particular, brief moment, the apparent simplicity full of beauty and sadness and truth.

October 22, 2021

The Second World War, by Dominic Sandbrook

I raced through this enthralling, vivid account of the Second World War, part of a new series written by Dominic Sandbrook for his eight year-old son. There's a lot of pluck and excitement, largely told from the perspectives of individual eye witnesses, ordinary soldiers and civilians as well as the brass. There are accounts from children caught up in the action, from women and ethnic minorities - the war not exclusively Boy's Own.

I raced through this enthralling, vivid account of the Second World War, part of a new series written by Dominic Sandbrook for his eight year-old son. There's a lot of pluck and excitement, largely told from the perspectives of individual eye witnesses, ordinary soldiers and civilians as well as the brass. There are accounts from children caught up in the action, from women and ethnic minorities - the war not exclusively Boy's Own.I should declare an interest: I know Dominic a bit, have made three short documentaries with him for the Doctor Who DVDs, and his history-for-adults book White Heat was extremely useful when I wrote my book on The Evil of the Daleks and my audio play The Home Guard.

Much of his account of the war is familiar - key battles, famous speeches, the real people who inspired the movies. What really struck me is how Dominic conveys the "world" bit of the war, cutting from events in Europe to Khalkin Gol or Singapore, or how the war in the deserts of Africa differed from experience in Burma. The Nazi attack on Stalingrad, for example, feels very different in the context of everything else going on at the same time.

It's all told in a breathlessly engaging, slightly tabloid tone, all short paragraphs and direct quotations. Yet this is skilfully peppered with nuance and an eye for historical irony. Here's Hitler touring the newly conquered Paris, having posed for photographs in front of the landmarks:

"At the chapel of Les Invalides, Hitler stood for a long time before the tomb of Napoleon, another ordinary soldier who had risen to become an all-conquering emperor. Then, without a word, he turned away.

For the man who had painted postcards [in Vienna], this bright morning in August 1940 was the greatest moment of his life. Twenty years earlier he had been a nobody. Now he was the master of Europe.

After just three hours, the trip was over. It was only 9 o'clock in the morning, but Hitler had seen all he wanted.

As they drove back the airfield, he said quietly: 'It was the dream of my life to be permitted to see Paris. I cannot say how happy I am to have that dream fulfilled today.'

At that moment, Speer glimpsed the lonely, pathetic human being behind the mask of cruelty, and felt 'something like pity' for him.

Then the mask slipped back into place, and Hitler's familiar stern expression returned. And a few minutes later, as silently as he had arrived, the dictator was gone. He never came back." (p. 128)

There are a few notable absences - such as nothing on the V2. But my only objection is the lack of an index and that Sandbrook doesn't cite his sources - "I don't have room," he tells us in his note on page 353. I find this frustrating with the Horrible Histories books too: that you can't check the claims made with such authority. "History is sources," as a former tutor used to tell us sternly. (And, ahem, it helps when I inevitably pinch bits of this to use in other things...)

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers