Andrew Collins's Blog, page 53

June 26, 2011

See Florence and die

Alright, I'm not after having a go at Florence of Florence Against The Machine here, nor against the photographer Desmond Muckian, who took this photograph of Florence and was asked to talk about it recently by the Guardian as part of a promotion for some music-based photographic prints they were giving away, and for their regular feature My Best Shot, where a photographer chooses their best shot. (I hope they won't mind me reproducing the photograph. If they do, I shall take it down. If they do mind, you can see it in situ here.)

What I'm doing here, by reprinting the article, based upon an interview with Desmond Muckian, is demonstrating how accidentally pretentious and preening one may sound when forced into a corner of self-analysis, and then transcribed from conversation to the printed page – especially as part of a feature where you are expected to crow about what you think is Your Best Shot. (I am already quaking at the hypothetical idea of a feature called My Best Album Review, or My Best Episode Of EastEnders, or My Best 6 Music Link, or My Best Unscripted Podcast Remark.)

This is an unkind process. My guess is that Desmond is a straightforward and likable individual, like all the photographers I've ever met, but he is also an artist, by the very creative nature of his job, and it is the artist who's speaking here. Because he was made to. I don't know if Private Eye still do Pseuds Corner, but it's a candidate, in full.

I make no further comment. We'll just let the man speak. But let it be a lesson to us all: be careful how seriously you take yourself, or your job. It doesn't always translate to the printed page. (Actually, if it was a photo of somebody with a bit more artistic depth and longevity than Florence, whose most famous song is somebody else's and has released one long-playing record in her career so far, it might not be so funny, I'll concede that.)

"Sometimes you manage to capture a magical, in-between moment; this is one of those. I took it on 11 February last year at a studio in east London, as part of a portrait shoot for the Guardian's Weekend magazine. Florence came in for three or four hours, and she was fantastic to photograph. She's really comfortable in front of the camera. You get the sense she's pretty comfortable in front of the mirror, too.

"She sang all afternoon. Somebody put a Mystery Jets song on the sound-system, and she sang a duet right there in the studio; it was quite moving. It also meant that I really wanted to come at the shoot from a performer's perspective.

"My idea was to capture an off-stage moment … I was just shooting away, trying to get a good portrait – then there was an extended silence. Florence turned away from me, and I just caught the moment … What I really love about this picture is that it draws you in. It's not the kind of image you'd expect to see of Florence; you don't quite know what's going on in her head. She has this whole persona: the big red hair, the long legs, the flowing robes. In this picture, you wonder whether she's hiding behind that.

"The best portrait photography lets the subject's personality shine through. It can be pretty pressured – you often don't have very long, and your subject has been photographed countless times before. You've really got to be prepared. Most importantly, you have to express something about them that's true. If there's no truth in an image, it's stillborn."

Having scrolled down through the comments left after the Guardian article, I must ask you to remain civil. We're not criticising the photograph, or the photographer, we are marvelling at the waffle.

[As I write, my rumour that Florence will be guesting with the Wombles at Glastonbury today - cultivated over the weekend and broadcast across the site with the help of Guy and Gez Worthy FM via 6 Music - still might come true. Let's hope so. She will go way up in my estimation if she yields to the solidity of the rumour and makes it come true, only revealing that she was Madame Cholet at the end of the set when she removes her Womble head.]

June 25, 2011

Week eight

This week's Telly Addict is mounted for your viewing pleasure, reviewing The Apprentice: Week Eight, BBC's Wimbledon montages, and Sky One's new fantasy epic Wall Of Fame. Hope you like it. The link is here.

June 24, 2011

La Haines

Luke Haines: genius. I like writing that because, having met him on a number of occasions, I'm pretty sure he'd hate being called a genius, while secretly thinking, Yes, I am one. He is one. I'm talking about Luke Haines the musician, essentially, whose output from the Auteurs through to Luke Haines, via Black Box Recorder and Baader Meinhof, has been prolific to the point of masochism over the past couple of decades, and inspired not by record company imperatives as much as by an apparently bottomless well of ideas and tunes. But I am here to write about Luke Haines the writer. Luke Haines the author. Luke Haines the chronicler. Luke Haines: historian.

Post Everything is the sequel to his first memoir, Bad Vibes, which I recommend to anyone who thinks they remember Britpop. Not the way Haines remembers it, you don't, and he was there, in the thick of it – a no doubt uncomfortable participant in the famous Union Jack issue of Select in 1993, photographed in grainy black and white in a deckchair, as I recall, but a player nonetheless. Scabrous, cynical, self-aware to the point of self-laceration and yet utterly arrogant and invertedly self-aggrandising, albeit viewed through blood-tinted spectacles, Post Everything picks up the story just before Black Box Recorder have a hit, and takes the story up to about 2005, just after the plug has been pulled on Haines' NT-funded musical about Nicholas van Whatsisface, Property.

The book, out in paperback on July 7 (with its cover sweetly illustrated by someone called Siân, whom we hope is his wife Siân), is bloated with bons mots, acute skewerings ("the Colonel Kurtz of the Curly Wurly Memorial Club, the Shoko Asahara of the Spangles Appreciation Society" – he's talking about my close personal showbiz friend Stuart Maconie) and sly observations (that John Humphrys so despises "Pop Music" he feels the need to add a question mark to both words when using the phrase on the Today programme: "Pop? Music?"). You will rattle through it, as Haines and co-conspirators seem to constantly defy the falling masonry of an imploding record industry, picking up "demo money" while being shown the door, and having hits when all around are losing their heads.

In among all the bleating and pissing and moaning, Haines actually proves an astute observer of what's going down, detailing the "digital recording genocide" of the ProTools revolution in the 90s with a clear head and no agenda ("by the early 20th century, every cell-of-one-man band can afford a ProTools set-up … the holy legacy of punk rock? Not quite, sunshine, not quite"). While other writers are driven by the tyranny of balance, or the politics of growth, Haines cuts through the shit. He errs on the side of grumpy, but when your author is falling in love, getting married and having a baby, you know that there beats a soppy heart within, and if anything, it makes you admire his jaundiced stance all the more.

Dropped by a succession of labels both cool and uncool, and hounded out of musical theatre by a succession of "Grahams", Haines has reason to complain about his lot. But, frankly, he never courted fame, and when it flirts with him, it's with the same barely disguised disdain as Bono, dragged to meet the author by Danny Goffey of Supergrass, of all people. What a wonderful world.

It all ends a bit abruptly, and there are a couple of "fantasy" sequences involving a cat that might have hit the cutting-room floor and been replaced by proper chapters about stuff that actually happened, but maybe Haines is flexing his fingers to become a novelist. I prefer him as a documentarian. His songs have always been fat with non-fiction, bulging with true stories and post-encyclopaedic knowledge, and his prose flies when it is similarly stoked. Post Everything is worth your while. Although if you haven't read Bad Vibes, get that first.

Blick house

Heavens, I know I'm late with this (busy week), but BBC Two's The Shadow Line was good. I hear that it divided people over its seven episodes, which ended last week with a number of bangs and a couple of whimpers, and right from the first episode, I could understand why it wouldn't be for everyone. Too Shakespearean. Too fond of itself. Too verbose. But Hugo Blick, who wrote, directed and produced it – a rare hat-trick indeed in television – created something really special. Although a cops-and-robbers crime drama, and essentially a long, drawn-out a whodunnit, it seemed to take its cue from The Wire in that its villains were as interesting and as human as its goodies, and its goodies as flawed and rotten as its villains. Indeed, both sides were "investigating" the same murder. Thus, Chiwetel Ejiofor's DI Jonah Gabriel was mirrored by Christopher Eccelston's Joseph Bede: both had cause to want to know who shot Harvey Wrattan, and both had channels through which to find that out. (Both had Biblical names, too.) A great set-up for a drama that rarely went where you thought it was going to go.

Blick is a masterful spinner of words. It may not be natural, or real, but it's ear-catching and rhythmic and audacious. If he was just a brilliant writer, we would cherish him. But he can direct, too. Some fabulous framing here, and an interesting use of sound – a heavily amplified cigarette being lit; various channels dropping out, while others remain in the mix; a tiny pop to punctuate the end of a scene; a vividly spat out lump of bloodied chewing gum on concrete. What fun he seems to have had. And if you think you've seen enough chase scenes in crime drama, you need to see the one that went on forever in Episode Two: you can never stay one step ahead of Blick for long – the chase was almost a metaphor, with us chasing him and never catching up with him. (Marion & Geoff was Blick's calling card, which he also wrote and directed; I never saw Sensitive Skin, but I know my parents really liked it. I have never met him, by the way – it would probably be embarrassing if I did now. Actually, the fact that he is the same age as me makes me a bit sick with jealousy.)

It goes without saying that The Shadow Line's cast represents some of this country's finest acting talent – and Ireland's – the towering likes of Eccelston and Ejiofor go without saying, as do Anthony Sher and Robert Pugh and Lesley Sharp, but what a joy to see Rafe Spall chewing the arse out of the scenery as the psychopathic Jay Wratten (a performance that could divide a room as readily as the dialogue), and Kierston Wareing (so strong in Fish Tank) stealing the limelight away from Ejiofor with a role that was so much more than sidekick; also Malcolm Storry as the loyal Maurice, Sean Gilder getting away from the pantomime of Shameless to play a doughty Customs & Excise man, and Stanley Townshend as the threatening Babur (I wondered if Townshend was Turkish, so effortlessly convincing was his performance, but he's blinking Irish).

We must praise Stephen Rea, as the man in the hat and gloves, Gatehouse, but for me, he was the only weak link. I still admire Blick for writing him, and dropping what seemed like a cipher, or a refugee from John Le Carré, into an otherwise gritty, contemporary drama. He was certainly striking. But he grew to irritate me. He remained remote and unreal – and I'm sure that was the idea – and that undermined the breath I felt on the back of my neck watching the other characters double-cross and triple-cross their way round an insurmountable problem, as the bodies piled up.

God bless the BBC for supporting talent like Blick's, and letting him run with an idea. Don't forget, The Shadow Line was not an adaptation of a novel, it was a one-off, authored piece, snatched from one writer's imagination, whose chances of a second series are – NO SPOILERS – somewhat limited! The BBC let him do that.

June 20, 2011

Mistah Kurtz: he dead

I first saw Apocalypse Now, the best film ever made, on Tuesday April 6, 1982. I had just turned 17, and saw it at the Northampton College of Further Education Film Society, of which I was a member (as anyone who's read this month's Word will already know). It "blew my mind," and I am quoting my 1982 diary here. I was already a mini-cineaste, as evinced by my membership of film club – for £6 membership, you got to see 36 films, many of them forbidden "X" certificates – but I'm still retrospectively proud of me for getting it from the word go. My friend Craig, and his girlfriend Rebecca, who accompanied me that night, did not like it. Again, according to the account in my diary, Craig said it was "Boring crap!" and Rebecca said it was "Rubbish." There is no accounting for taste, but I was baffled at their bafflement. I wrote: "I'm so frustrated about everyone hating it. I've just seen a cinematic masterpiece."

Francis Coppola's masterwork was already a couple of years old in 1982, having been released in 1979, but it was as good as new to me. Of his oeuvre, I had, at that stage, only seen The Godfather Part II, so was not exactly his biggest fan, but over the next year or so, I caught up with The Conversation, The Rain People, The Outsiders, Rumble Fish and, well, The Godfather, and it started to fall into place: he was my main man. The more I read about him, the more I realised that this was the classic case of an American auteur channelling European influence, indicative of a much wider movement in Hollywood in the 70s, but I was coming at Apocalypse Now without intellectual baggage. I just knew it was a Vietnam war movie that had been a nightmare to shoot. My reaction to it was pretty organic and raw. I loved it because I loved it.

The next time I saw it was in 1983, when my friend Paul and I rented the video, and we not only watched it more than once, we taped it onto audio cassette, all the better to immerse ourselves in it, and learn it. In 1984 – the same year we experienced it on the big screen for the first time on a Nene College excursion to London, during which it happened to be playing at the Prince Charles Cinema in Leicester Square – we purchased the gatefold soundtrack album, which including huge swaths of dialogue. A bigger boy at Nene, a punk called Jon, claimed to have dropped acid and listened to the LP on headphones, and said it was like "going to Vietnam." It wasn't certain that Jon had even come back. (Neither Paul nor I were going to be dropping acid to find out.) By now, you can sense, Apocalypse Now was my life.

I'm often asked what is my favourite film of all time, and if I'm honest, I should say The Poseidon Adventure, as it is my favourite. But the best film of all time? That can't be The Poseidon Adventure. It has to be Apocalypse Now. It must be the film I have seen the most times, in full. I really can recite it. That may sound a bit childish, but seeing it is like listening to a favourite album, whose lyrics I have learned by heart. It never lets me down. I've seen it on tape, at the cinema, remastered and in Redux; I've listened to it; at one feverish, teenage stage in 1983, Paul and I acted out a full-length parody of it! (The cassette may even still exist somewhere. Don't ask me to dig it out. Oh, you weren't going to.) For the release of Redux, while at Radio 4, I got to interview cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and sound editor Walter Murch. A great day, even though Murch was a grumpy bastard, and didn't even get up out of his chair to shake my hand. By the way I've never seen the bootleg 289-minute cut.

Anyway, with the film out in a "restored" Anniversary Edition – which is the 2000 edition – at selected cinemas, and on 3-disc Blu-Ray for the first time (which would be exciting news if I had a Blu-Ray player), I allowed myself the adult treat of going to see Apocalypse Now at the reasonably new Curzon Millbank in London.

Plenty of people in, considering it was a Sunday morning 11.30am showing, and tremendous to see it digitally projected, and with digital sound, although don't get any funny ideas about the remastering turning it miraculously into an HD picture: it still looks satisfyingly like a film made in 1979 – indeed, some of the murk and the desaturated greys indicative of the late 70s are precisely the kind of effect all sorts of modern filmmakers thrive to achieve through digital fiddling. You don't really need me to review the film, but I will review my latest viewing of it.

I suppose it's no weirder going out to the cinema to see a film you know than paying to go and see a band whose back catalogue you can sing, but Apocalypse Now conceals no more secrets for me now: I know where you can spy the title of the film; I know which of the crew of the PBR dies and when; I know what's in the jungle when Chef and Willard get out of the boat; I know what type of board Lance prefers; I know what happens when the Vietnamese woman chucks a hat into the helicopter; I know what happens when the Playboy bunnies are helicoptered off the stage; I know how Clean's mom's recorded message plays out; I know what books Kurtz has in his hut (spoiler alert: From Ritual To Romance by Jessie L Weston; The Golden Bough by James Frazer; The Bible - much of which fed into what I was studying at A-level in 1982 ie. The Waste Land by TS Eliot); I know how it ends, with a whimper and not a bang. None of this reduces my awe.

The 2000 version is true to the original, in that it has no end credits, and just ends. A later version instated credits, which played over footage of the sets being burned, which audiences – me included – mistakenly took to be an air strike on Kurtz's compound, when in fact the footage had no connection to the film itself. It's weird to see a film at the cinema with no end credits, I'll tell you that much. No time to decompress. Just "the horror, the horror" and it's house lights up.

I'm so glad I made the effort to see it again. I have it on DVD – I could watch it any time I liked – but there's still something magical about seeing a film you love on the big screen. Oh, and if you think the headline displays casual racism, it's mah favourite quote from Eliot's The Hollow Men, itself a quote from Conrad's Heart Of Darkness. Aren't we all clever? I realise now that I loved Apocalypse Now as a teenager in the same way that I loved Monty Python and the NME as a teenager – because they taught me about things that I knew not of. If ever a film required footnotes, it's this one. Here's to the next time!

June 18, 2011

TV eye

Made it. My seventh Telly Addict column for the Guardian website this week actually carries a warning about "scenes of a sexual nature." In it, I'm reviewing the sexy Camelot on C4, plus the positively unsexy Kill It, Cut It, Use It on BBC3 and the return of Luther on BBC1. The link is here. What you hopefully won't be disturbed by, due to clever lighting and chair-positioning by producer Andy, is my partially bloodshot right eye, which I woke up with on Tuesday, possibly due to Breakfast shifts, stress and overwork, and a passing cold. It looks horrible in real life, but seems to be pretty much concealed on the tiny telly in your computer screen. Phew. You were warned. Still, the new shirt looks nice!

June 13, 2011

Origins are the only fruit

Again, the Curzon cinema supplements its diet of arthouse, foreign and independent films with a garden variety blockbuster, albeit not exactly a dumb one: X-Men First Class, which I have been looking forward to not because I am a Marvel nut with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the source comics, but because I liked the first three films. (I've never seen the one about just Wolverine, as he was always my least favourite X-Man. Let me know if I've made a massive tactical error.) The new one, directed by Matthew Vaughn, who was all set to direct X-3 but had to pull out – regretting it ever since – also has Jane Goldman's name on the credits, which further enhances her reputation of one of this country's hottest screenwriters, particularly in the fantasy/sci-fi/comic book genre. If she keeps this up, pretty soon they'll have to start calling Jonathan Ross "Jane Goldman's husband," which I'm sure he would welcome.

Although US-sourced, X-Men has a deeply English root, namely Professor Xavier, Oxford-educated young gentleman whose estate where the mutants are fostered and schooled, is in upstate New York but may as well be in Berkshire. First Class, an origins story to match Batman Begins and, although vastly superior, the second Star Wars trilogy, opens with Xavier as a boy, meeting Raven/Mystique, in his Westchester kitchen, the same year, 1944, that the future Magneto is being tortured by the Nazis and discovering what his unlocked anger can do to nearby metal. From these beginnings, it shifts forward to 1962 and the Cold War, and cleverly presses the actual Cuban Missile Crisis into service as a plot device to unite the seemingly unready young X-Kids in battle, and to test out their mutant superpowers off the Cuban coast. This film is drenched in special effects – there were so many technicians and digital wizards working on First Class, the closing credits were forced to stack them into five columns in order to cram them all in before the music finished. There are a number of money-shot set-pieces, all of which build to the nuclear stand-off on the cusp of the blockade, but strip away all the binary code, and you're still left with a decent script, some good gags (James McAvoy, as the young Xavier, on being granted his professorship, says, "I'll be going bald next" – a sly reference to the fact that Patrick Stewart will play him in much later life), and a credible narrative jigsaw which lays all the key pieces out on the table, such that not only do we understand how the gang got together, but leaves plenty of room for further adventures with the handsome actors before they turn into theatrical knights.

A fine cast includes Michael Fassbender, whose move from indie hunk (Hunger, Fish Tank) to mainstream hunk has been seamless, the aforementioned McAvoy, Winter's Bone star Jennifer Lawrence (who I recognised but couldn't place until the credits rolled), January Jones off of Mad Men (who, as has been pointed out elsewhere, was mainly bra), Nicholas Hoult from Skins, and Jason Flemyng, another Brit who seems to be taken very seriously by Hollywood. Sometimes I wonder if actual American actors feel a bit threatened by the current influx of Brits, going over there, stealing their jobs – and probably their women. (Great to see Michael Ironside as the captain of the US Navy warship charged with firing on the Russians during the Missile Crisis, though.)

Under the aegis of Bryan Singer, it seems that X-Men is one of the more reliable comics franchises. You have to suspend your disbelief a bit – I mean, how come the X-Men could appear out of the sky in a black stealth jet to prevent Russia and America from starting a nuclear war and not get blown out of the sky? – but it present an alternative history that almost hangs together. And of course, in the mutants, it reaches out to nerdy teens everywhere and tells them to be themselves and not be bullied into conforming. Not that they'll listen.

June 11, 2011

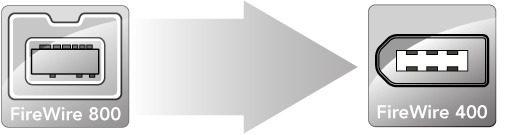

Niiiiiiiiice

Well, here's an unexciting picture. But it means something really heavy. It means there are nice people in the world. It's easy to start imagining that the world is cruel and heartless place, exclusively populated with people looking out only for themselves and barging everybody else out of the way. But then someone like David James, aka @vidjam on Twitter, sends you two Apple FireWire adapters out of the kindness of his heart, and your faith in humanity is restored.

I was, as you may remember, moaning on about Apple the other week; how I'd bought a brand new MacBook Pro and that they've changed the FireWire dock so that I can now no longer charge and sync my old iPod with my new laptop, and that surely if Apple are insistent on constantly upgrading and improving their products they should reward early adopters and brainwashed followers of their shiny cult by allowing them to exchange now-defunct cables with brand new ones, or leapfrogged versions of hardware with new ones, at no extra charge … Anyway, I am a stubborn bastard and had decided to refuse to pay Apple another penny for a cable that I only needed because they'd changed the sockets on their equipment. I was going to punish them by punishing myself. That would show them. I'd charge my iPod using my old MacBook, and sync it using my new one, as laborious as that would be.

I didn't really think that Apple would read my blog or my Tweets and send me a cable. They don't seem to work like that. However, a fellow Mac slave – @vidjam – got in touch via Twitter and offered to send me an old FireWire-friendly charger that he no longer uses. This was beyond kindness and I offered to send him something in return like a CD or a book, which he politely refused, citing the hours of free podcasts that I have given him with Richard over the last three years. This, he said, was payment in kind. Kind is the operative word. He didn't need to do this. And he was paying for the postage.

I went into 6 Music this morning, for the first time in a couple of weeks, to empty my pigeonhole and there was the expected jiffy bag, which did indeed contain the FireWire charger for the old iPod: a heartwarming act of recycling in itself in a clogged up world. I smiled on opening it. However, as well as the jiffy bag, there was an envelope from Amazon with my name on it, which confused me. I had ordered nothing from Amazon. Well, guess what, this packet contained a further adapter – FireWire 400 to 800 (with me, nerds?) – which @vidjam had, without prompting, also ordered and paid for and had sent to me. This is beyond nice.

So, let us praise David James for his two acts of niceness. Niceness is an undervalued commodity. I have spent 23 years in showbiz, during which time I have always endeavoured to be nice. I know that this will not lead to any kind of swashbuckling showbiz reputation, and you can never quantify whether or not it will lead to further work, but it helps me sleep at night, and if it means I am taken for granted, or forgotten about, or passed over, then so be it. I'd rather try to be polite and helpful and jolly and reasonable. It takes less muscles to be nice than to kill people, I think. (I was once in talks about publishing a book of my collected journalism; I had the title – Punctual.)

This post has not been about Apple, or computer hardware, it has been about being nice. Be nice.

Ticking boxes

Ah, here I am again, in a little box on your computer. Telly Addict this week looks at Jason Isaacs' new TV detective in Case Histories, BBC1; the quagmire reality show Our War, BBC Three; and format copycat The Restaurant Inspector, Channel Five. Well, it doesn't. I do. I can obviously never embed it, so the link is here.

June 10, 2011

Insect flak

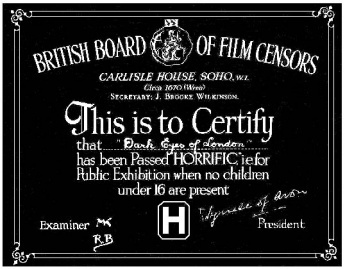

You'll have heard that the sequel to gross-out horror movie The Human Centipede – Human Centipede 2 (Full Sequence) – has been refused certification by the British Board of Film Classification. Where does this leave a prudish liberal like me, eh? I am, in the marrow of my bones, against artistic censorship. I believe in free expression, and for free expression to be placed in the public arena where it may be judged, or ignored, by the public, in context, as long as no animal or human being was harmed in its making. At the same time, I find the subject matter of The Human Centipede and its sequel – and the gleeful exploitation of that subject matter – revolting and obscene, and I believe that its squalid place in the "torture porn" pantheon represents an irreversible coarsening of our culture, and I'm glad the BBFC isn't letting them get away with it. Confused? I certainly am.

I had an angry letter published in the Radio Times in 1988 when BBC2 aired one of cinema's greatest works Apocalypse Now and presented a butchered version, in which the word "fuck" was painstakingly removed or dubbed over – such that anyone who, like me, had pretty much memorised the whole film (we all did that, right?) would feel each snip like a knife to the ribs. This, I pointed out in my letter, was a film about the horror of war, and one of the "fucks" they excised was the one in Colonel Kurtz's speech where he bemoans the fact that the US military won't allow its pilots to write "fuck" on the side of their aeroplanes and yet they train them to drop fire on people. This irony was, I suggested, lost on the BBC's moral guardians. (Needless to say, another reader wrote in to complain about my letter and accused me of getting off on hearing curse words. Cunt.)

I watched the first part of BBC3′s surprisingly good reality show about the war in Afghanistan, Our War (no, Your War), based on actual helmet-camera footage from on the ground with the 1 Royal Anglian regiment, and it effectively showed the death, in April 2007, of 19-year-old Private Chris Gray. Now, clearly his family had given consent, and appeared on camera, and it was sensitively framed and contextualised, and indeed acted as a moving memorial to another young life snatched by war, but some would argue that the BBC should not broadcast a soldier's death (it occurred in the dusty confusion of an ambush but you saw his dead body being carried away), and that the Ministry of Defence should not have released the footage. I disagree in this case. This is not presented as snuff; it's a human story with a human message. A similar argument – political, ideological and moral – can be had about whether we have a "right" to see footage, or photographs, of Osama bin Laden's corpse. At present, those images are censored. But they are not artistic.

In 1988, a young man in the first real heat of ideological indignance, I likened cutting the "fucks" from Apocalypse Now, which was shown long after the watershed, to cutting pieces out of the canvas of the Mona Lisa. I still believe that. And the nasty makers of The Human Centipede 2 (Full Sequence) – in which a pervert masturbates with sandpaper over a DVD of the first Human Centipede film in a metatextual masterstroke – plan to appeal the BBFC's verdict. They may yet cut a few seconds here and there in order to win a certificate. This happens all the time. It happened to the apparently rather unpleasant A Serbian Movie last year, which won its release.

The BBFC were very clear about why they have effectively banned The Human Centipede 2: their report heavily criticised the film as making "little attempt to portray any of the victims in the film as anything other than objects to be brutalised, degraded and mutilated for the amusement and arousal of the central character, as well as for the pleasure of the audience" and that the film was potentially in breach of the Obscene Publications Act, meaning its distribution in the UK would be illegal. The BBFC actually said that "no amount of cuts would allow them to give it a certificate". So, we may never legally see this film. (I managed to get my hands on a pirate video copy of A Clockwork Orange and saw that while it was still banned. And this was before the Internet.)

However – and I'm as guilty as anybody for adding to the chatter – The Human Centipede 2 is now the most famous film in the world. Even people who hadn't noticed the first one have heard of it now. The BBFC have, with the best intentions, made it a cause celebre. Imagine how alluring it will be, especially among teenage boys, now that it's forbidden fruit!

I suspect I will never see it, either way. I don't want to see it. I didn't want to see The Human Centipede, and easily avoided doing do. I watched the trailer and it made me feel ill. So should they actually ban the sequel? The idealist within me says no. If it causes a sick person to do something sick, why should art be censored for everybody else on account of that one sick person? This is a murky area, I know, as I hated the bit in episode two of BBC2′s incredible drama The Shadow Line where Rafe Spall appears to drown a cat. He didn't really. I don't imagine a cat was harmed – although a real one walked away looking pretty wet, and they hate being wet – but I really worry that some idiot somewhere will copy what they saw on TV. People can be incredibly stupid, and I genuinely believe that people have never been as stupid as they are now. But can we censor everything because of stupid people? (I'm hoping that The Shadow Line is so intelligent, very few stupid people will have still been watching by episode two.)

If you think I'm going to provide an answer to this dilemma, I'm not. But I'd like to talk about it.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers