Andrew Collins's Blog, page 52

July 23, 2011

You're tired!

No, I'm tired, having done two weeks on 6 Music Breakfast, plus my usual Zoe Ball breakfast slot on Saturdays, and then a Saturday morning show on 6 Music, while co-writing and script editing a new sitcom for Sky1, and fulfilling my Radio Times duties, which this week included transcribing and writing my JJ Abrams interview, and having a meeting at C4 about another sitcom pilot I'm working on. But still, with my eyelids propped open, I watch three whole television programmes so that you don't have to and sit in a studio at the Guardian and say words about them to a camera. I love it, of course, and have no right to complain as having no work would be much worse (because, as a self-employed person, no work means no food), and the rewards are not exclusively financial: the reward for doing Telly Addict for the Guardian is the appearance, overnight, every Friday, of the little box with my tired old face in it, skilfully edited into the clips, like this one, which is, amazingly, my twelfth. In it, I review The Apprentice: The Final on BBC1, Show Me The Funny on ITV1, and The Hour on BBC2. Do not click on the … oh, you already have. What more can I do?

July 22, 2011

World of the news

OK, the news. Preamble: in 1999, I was writing for Heat magazine. Seems unlikely now, but when it was first launched by Emap – the publisher for whom I'd worked on Select, Empire and Q before I went freelance – it was not the epoch-defining behemoth of celebrity tittle-tattle and eugenics that it is today; rather, it was a typically middlebrow attempt at a British Us Weekly: a bit of everything under one roof. To give you an idea of how different it was in its first, not-very-successful incarnation, I was commissioned to write a 1,300-word double-page spread comparing books about serial killers ("Dahmer cooked and ate the bicep of one victim with salt and pepper and steak sauce: 'My consuming lust was to experience their bodies'"), and another comparing books about war (quoting Anthony Beevor's Stalingrad at this much length: "The silence that fell on 2 February in the ruined city felt eerie for those who had become used to destruction as a natural state. Writer Vasily Grossman described bomb craters so deep that the low-angled winter sunlight never seemed to reach the bottom, and 'railway tracks, where tanker wagons lie belly up, like dead horses'"). Confusion initially reigned about what tone the new weekly should take. It was on fire in the TV ads, but not in real life.

Anyway, I was dispatched to interview Chris Tarrant, by then a huge TV star again thanks to Who Wants To Be A Millionaire. It was a hugely enjoyable interview and I delivered the copy. However, there was a problem. I hadn't asked about his estranged stepson. I'll be honest, I didn't even know he had a stepson, estranged or otherwise. But it had been in the tabloids apparently. And, sensing a certain lack of newsstand appeal, the editors of Heat seemed to want to move into a different realm. I was pretty mortified to have to go back to Tarrant's PR and request a "top up" chat with Chris about this urgent matter that I had failed to ask him about on the day, too busy was I asking him about Tiswas.

Tarrant was, I felt, gracious in agreeing to a bonus 10 minutes on the phone. He was in the back of a car being ferried somewhere, and, forewarned, he knew I was calling about more personal matters. I apologised for what I was about to ask him, and explained that I was under the cosh, but he said fire away. This is what I had been instructed to ask, and what he said, and what was printed, in full, at the end of the subsequent interview in Heat (you can skip past it if you're not interested in a TV presenter's relationship with his stepson in 1999):

Your 18-year-old stepson Dexter told one of the tabloids last year that you had thrown him out, saying, "Chris was an egotistical pig who tried to buy his family's love with money." What went on there?

The bottom line was, he wasn't thrown out, he chose to run off into the night because he didn't like the idea of doing a day's work. It was very hard at the time, particularly on his mum, very upsetting all round. He and I are now having a continued dialogue, we're working towards a sort of amicable reunion. He made his protest like all kids at 18 do, but had no idea that it was such a ridiculously high-profile thing to do. It happens to half the families in the country, but unfortunately because he's my kid it became a big deal. Dexter himself has been amazed, horrified and saddened by this huge public profile that he then got. He's cool, I spoke to him yesterday.

Other than that, the press have been pretty good to you haven't they?

Until Heat really. Those stitch-up bastards!

As you can see, he accepted his fate as a public figure with tabloid form with good humour and honesty. But I felt dirty. I was a freelancer, so I was cutting off a revenue stream, but I made clear that I was uncomfortable with this type of work, and I wasn't asked to write any more profile interviews. As it turned out, the magazine turned a corner when Mark Frith took over the rudder and the launch of Big Brother decided the magazine's fruitful fate. I was no longer required, and nor were my 1,300-word book pieces. (I guess the real irony of all this, is that David Hepworth and Mark Ellen were the launch editors – and it was Mark who'd sent me back for the extra tabloid content on Tarrant. Now, both of these men understand magazines, and Mark has a natural instinct for how to tell a story, which he uses when commissioning and editing for Word, but a more decent, honest, faithful and true pair of gents you would not meet. It does seem bizarre now that they started Heat. But they did.)

This was my first, last and only flirtation with tabloid journalism, and even then, at one remove from the real thing. It's not my strong suit. I'm rubbish at getting the killer quote. If I ever have got one, it has been by accident. My interview style is to try to find some common ground and develop a matey rapport with my interviewee in the allotted time, which can sometimes lead to a relaxed enough attitude for enlightening stuff to come out. Most of the time, you just get a chat. I'm happy enough with this, but don't come to me for a scoop. Leave that to the journalists.

As we speak, the profession of journalism seems to have split down the middle. On one side, we have the venal, unscrupulous, immoral, bloodthirsty, phone-hacking News Of The World scum; and on the other, the noble, investigative, truth-seeking, establishment-undermining Guardian knights in shining armour, who broke the phone-hacking story, and dragged it out into the open from the shadows of nepotistic self-interest and corruption. It is worth stating that not all tabloid journalists are scum. Not all journalists are tabloid journalists. And not all non-tabloid journalists are saints. Equally, not all journalists who worked at the now-defunct News Of The World were involved in illegal phone-hacking. But it seems fairly likely that journalists at other tabloid newspapers will have also paid for phones and emails to be hacked; after all, if it was common practice at one Sunday tabloid, it was probably on the menu at the others. After all, the newspaper market, in decline now, has always been pretty cutthroat. At the visible end, we've seen price cutting, bingo wars, spoilers and endless free CDs, DVDs, downloads and Greggs steak-bake vouchers; behind closed doors, far worse goes on.

"Tabloid journalism" is not restricted to the tabloids. Everybody's after a quote or a headline, a line it can sell, whether it's the Sun, or 6 Music News, or Radio Times. Tabloid mentality is endemic, and as the media marketplace becomes ever more frantic, attention spans more microscopic, and the meat on the bones of the available audience ever more scarce, tactics will get dirtier. Or maybe, now that the deletion of texts from a murdered schoolgirl's mobile stands as the flashpoint for the current crisis of confidence, tactics will have to be cleaned up. At least until we've all forgotten about it.

Rupert Murdoch, James Murdoch and Rebekah Brooks are merely the most public and most powerful faces at the centre of the current circus of death. It's easy to hate an apparently vulgar old billionaire who effects dodderiness when it suits him, and yet rules one of the biggest media empires the world has ever seen, so can't actually be that doddery. It's just as easy to hate a jumped-up, Harvard-educated corporate automaton and heir, who speaks in a monotonous American accent and exclusively in legalese. And it's even feasible to hate the woman who launched the "name and shame" campaign, even if that was the only alarmist stunt Rebekah Wade/Brooks ever pulled while editing a tabloid newspaper. They all claim to have been clueless, which is a counter-intuitive quality for chief executives of multi-million-dollar companies to show off about, when you think about it. I rather expect my bosses to know everything.

And when key News Of The World shopfloor whistleblower, Sean Hoare, is found dead – a death that is without suspicion in the same way that David Kelly's was – it's easy to feel a certain degree of sympathy for the reporters who were the last contact between their newspaper and a revolving cartel of seedy private investigators with loose morals and a tendency to go through bins. Hoare said that he and other reporters endured a climate of fear: get the story or else. The blame must go to the top. The bankers played with our money. The media moguls play with our heads.

But let us not think ourselves morally superior to all this. Or to absent ourselves from the morass. We're all responsible for the culture that took us to this particular brink … unless you have actually ignored celebrity tittle-tattle since 1969 when Murdoch's brand of lowest-common-denominator sensation began ("HORSE DOPE SENSATION"). I have never really been a tabloid reader in adult life. My Nan used to bring the Sun round our house on a Thursday, and as a teenager on the cusp of discovering sexism and Labour party politics, I used to flick through it for easy, "ironic" entertainment and funny things to cut out and stick in my diary with Pritt, like frames from the cartoonishly erotic Axa comic strip, and disembodied soaraway headlines. I would soon be under the Guardian's spell, once I got to college.

Ironically – and I don't mean "with irony" – I bought the Sun pretty much every week for three years between 2008 and 2011 so that Richard Herring and I would have something topical to make jokes about on our weekly podcast. We also bought the Mail, but mocked both for their poisonous and laughable idiocy, and in our own way, I hope, atoned for the 20p and 50p we paid out for those rags. But I've also bought the Sunday Times for my own use on a Sunday because I like the Culture section, and on occasion the Saturday Times, because I like the books section (which I've sporadically written for), so I'm in trouble when it comes to the absolutist stance of the cancel-your-Sky-subscription lobby – most of whom, I fancy, pay to see films made by the Murdoch-owned 20th Century Fox, or buy books published by the Murdoch-owned HarperCollins, or watch ITV, in which Murdoch has a 7.5% stake, or watch the Murdoch-owned National Geographic via another satellite provider. (And if they don't, I congratulate them. Truly. I avoided Starbucks for years after reading No Logo, and then I read that Naomi Klein occasionally uses Starbucks if it's the only coffee outlet available, say, at an airport, so I calmed down.)

It's been a hell of a week for the top brass at News International and News Corp. The latter's bid to buy the remaining 61% of the shares in BSkyB is dust. Execs including Brooks, Andy Coulson, Les Hinton and Neil Wallis, have either resigned and gone home, or resigned and then been arrested and then been released and gone home. The toppermost of the top brass have been called before a Parliamentary select committee, beamed all around the world, there to squirm beneath the desk, get the words "humble" and "humbling" mixed up, dish out platitudes and apologies and denials in the same voice, and in one soaraway instance, almost get some shaving foam on them. (All the while, the Metropolitan police, who appear to have been up to their necks in News International appeasement, are shedding chiefs by the day, to the point that – gasp! – a woman might have to be drafted in to save them.)

It's been gripping telly, and although the newspapers have been perhaps unnaturally biased towards coverage and analysis of just the one story while the Eurozone and the United States have been on the brink of economic collapse, again, it's been engrossing to read. It's ironic that the news is the news, and that the news has drawn people back to the news, whether on the news channels, one of which is 39% owned by News Corp, or in the newspapers. I don't usually like to see 80-year-olds being humiliated on television, but I do like seeing the most powerful people on the planet humiliated, so I didn't stay conflicted for too long on Tuesday. And as someone who also bangs tables when he's making a point, I even sympathised when Murdoch Sr was told by his wife to sit on his wrinkled hands.

But we are all to blame, as I say. The celebrity culture, whereby fame can be achieved by selling a story, or appearing on a stupid reality show, or having breasts, makes mugs of us all. Even looking at the headlines of the Sunday tabloids while picking up our Observer - just to see, ha ha, what they're frothing about this week, oh, it's Cheryl Cole – makes us complicit, even if we don't hand money over the counter. So let's not be too smug here, unless we are truly without sin. I will say this: Piers Morgan must be squeaky clean if he's prepared to challenge Louise Mensch the way he did on CNN on Tuesday night after she collated two passages from his book The Insider and made five, using Parliamentary privilege as a fig leaf for basically accusing him of phone-hacking during the hearing, which he denies.

Equally, you have to hope that nowhere down the line has anybody working for the Guardian done a dirty deal in an alley to get information at any point, otherwise its overarching smugness might too turn to albumen. (You have to hope that there are some good guys somewhere on Fleet Street.)

Rupert Murdoch's empire seems unlikely to strike back. If it turns out that victims of 9/11 were hacked, then it gets really nasty for him back home, as the Americans done like it up 'em, and I think I'm right in saying that corporate justice is much more bullish over there. We're giving Man and Boy a fair old roasting over here, even though the parent company is based in the US, and he's not from round these parts. Maybe a world where media empires don't exist would be a better one, although the one I do a lot of my work for, the BBC, is a global force to be reckoned with, and that's why the rest of the media are so enthusiastic about bringing it down. (The deal the government did in 2010 after which the licence fee was frozen, necessitating redundancies and property sell-offs and the threat to bring back the testcard, was done, we must now assume, at a time when News International ran the country. The NUJ are certainly asking the question: can we look at that again, in light of recent developments? If it's a battle between the BBC and News Corp, I know whose side I'm on.) I don't think David Cameron will be gone by Sunday, by the way. We shall see.

Sorry, going on a bit. But it's a big story, and I've been too busy to tackle it this week. Some once powerful men and at least one woman might go to prison over this. The Met are going to have to clean up their own back Yard. News Corp will surely sell News International, and another publisher will be delighted to buy the Sun at a knockdown price, which remains a very popular newspaper, and the Times, whose heritage and reputation cannot be knocked up overnight (but which doesn't make any money, and whose courageous paywall has yet to create a domino effect through the British newspaper industry). But will "the culture" look any different when the fuss has died down? We live in a post-News Of The World world. But its readers seem to have simply migrated to the Star and the Sunday Mirror and the People, because millions of British people wish to be entertained and titillated on a Sunday. And a Monday. And a Tuesday.

Like boxing, if you ban stupidity, it will only go underground. And anyway, isn't Google far more sinister and powerful than News Corp? Discuss.

July 21, 2011

America's last top model

I've been writing this week about meeting JJ Abrams, for Radio Times. You can read the feature in next week's issue, should you wish; it's based on an interview I did with him in May, when very few people had seen Super 8, his new family monster movie set in 1979 and produced by Steven Spielberg, to whose 70s work it seems clearly to be a tribute. (It is. It's an explicit tribute.) But it's the above scene – grabbed from the film's trailer – that intrigued me the most, as it features the Aurora glow-in-the-dark model of the Hunchback of Notre Dame, which I was given for my ninth birthday, in 1974. Although the company has been bought and sold a number of times since its 60s heyday, the horror icon model line, licenced through Universal, seems to have endured. I grabbed this shot of the box from the internet, where many a finished model, fully and meticulously painted, also appears.

Props to Abrams for mining his own geeky, movie-obsessed childhood for detail like the Hunchback model, seen being fastidiously painted by Super 8′s lead character Joe (Joel Courtney) in a scene that beautifully encapsulates the often solitary bedroom-bound existence of the young suburban nerd. As it happens, I painted my models out in the garage, where my vast range of Humbrol enamel paints were stored, and what hours of concentrated enjoyment I gleaned doing just that. Over the ensuing years, via birthdays, and swapsies at school, I collected pretty much the whole set of Aurora Universal monsters: Dr Jekyll/Mr Hyde, Frankenstein's monster, the Mummy, King Kong, Godzilla, the Phantom of the Opera and the Wolf Man. I also had Salem Witch, which didn't seem to be from a Universal horror film, but whose bubbling cauldron of bats and eyeballs was a fond favourite.

The Aurora horror range combined two of my early childhood loves: horror movies, and making models. I would pore for hours over the Airfix catalogue, trying to plan which model I would purchase next when pocket money or present-receiving opportunity would allow. I loved sticking them together, although the greatest thrill lay at either end of the process: handling the pieces when fresh out of the box and still affixed to the plastic frame, while absorbing the instructions, and then applying the paint at the other end. It's funny how a tiny detail about the glow-in-the-dark model became my first point of bonding with JJ Abrams, who was born a year after me. Having seen the Hunchback in the film – and with a 35-minute slot during which to win him round and get him to say interesting things into my tape recorder – I told him how much it meant to me and we were suddenly discussing the etiquette of whether or not to paint over the fluorescent parts of the model (in the Hunchback's case, his head and his back glowed, an aspect that actually freaked me out from my bedside).

I loved my kit models. I was a member of the Airfix Modellers' Club. I still have the membership card somewhere. And yet, "club" was a misnomer, as modelling never won me any friends, nor led to any social interaction. It wasn't exactly a group activity.

I never think of myself as the classic nerd. I spent a lot of time with friends, climbing trees, wading through streams, playing cricket and hide-and-seek. But I do celebrate the nerdiness gene, as it gave me time to think, whether I was sat up the dining room table meticulously creating my own comics, or out in the garage adding the decals to an Airfix model of an RAF Refuelling Set. (I did actually have that. It was brilliant.) My brother and I were obsessed with catalogues, and got as much pleasure looking through them as actually ever owning any of the stuff within.

That is all. I made the schoolboy error of looking at a thread about Collings & Herrin on the Word message boards after being alerted to its existence. As usual, a number of people who I would normally expect to ally myself with, being keen Word readers, heaped abuse upon me, and one called me a "gigantic bore" for writing about the past. He can actually fuck off. I find the past endlessly fascinating, especially the way it unites us, across continents sometimes. And anyway, the future looks pretty shit to me.

July 18, 2011

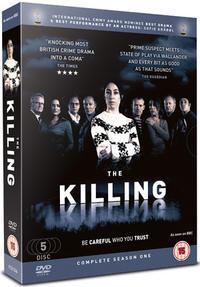

I could murder a Danish

Some late news just in. The Killing is a good television programme. I know, I know, get hip to the beat, Granddad, but when was the last time I got in early with something? I mean, really. I do not set trends. I follow them. Usually after everybody else has stopped following them due to lack of interest, and because a better trend has just started up somewhere else. And if I'd paid attention to my Radio Times colleague Alison Graham – who just sits over there from me in the Radio Times office, and anyway, even if she didn't sit over there, she highly recommended The Killing the week it started on BBC4 in the Radio Times, a magazine I read – I'd have been in at the ground floor. But I didn't, and wasn't. And then it was too late.

I mean, it was old news to the Danes when BBC4 started showing Forbrydelsen ("The Crime"), having aired, and been a hit, on Danish television in early 2007. I can't remember exactly what was on when The Killing started here, but it must have been a handful, as we never series-linked it – perhaps it clashed with something else? – so by the time the MEDIA had spotted it, about six episodes in, it was too late to practically catch up. (And iPlayer is great, but I don't like watching telly on my laptop – it eats up my wi-fi allowance for a start, and it's too small, and I've tried hooking it up to my telly, but it's not happening, right?) Hey, I was cool with having missed the start. I missed the start of The Office. I missed the start of The Wire. I missed the start of The Inbetweeners. I miss the start of everything. But BBC4 are smart, I thought – they'll just show the previous episodes as a "catch-up", maybe in the middle of the night, and we can draw up alongside, majestically. But they clearly didn't have the rights to repeat The Killing, and The Killing remained an exclusive pleasure of a) early adopters, b) Alison Graham disciples, c) people who don't mind watching things on the iPlayer, and d) some Guardian readers. Not all Guardian readers. But some.

At this point, I became as stubborn as a mule. If the BBC, which I'd already paid for, wouldn't show The Killing again from the start, I would not – that's WOULD NOT – shell out for the DVD box set. I remained unanimous in this. It became a badge of honour. When the box set came out, I did not buy it. Friends who did buy it found themselves with waiting lists, as others put their hands up to borrow it. So much time passed, I wondered if I would ever see this bloody programme.

BBC4 announced that they had purchased series two of The Killing. C4 announced that they had purchased the US translation of The Killing. A-boo! How could I watch either of these things without having seen the original. And then Zoe Ball stepped in. She lent me her box set, even though she was only halfway through it, as she couldn't foresee sufficient quality time ahead to fit any more of it in for the next two weeks. Grateful, I brought hers home with me after appearing on her Radio 2 show last Saturday. And I must give it back to her next Saturday. This will not be a problem. I've nearly finished all 20 episodes.

The Killing, or Forbrydelesen, which feels a more respectful name for it now that I have been sucked into its Danish ways, is superior, intelligent television. It's a whodunit, if you didn't know that already, with echoes of Twin Peaks in that there are a lot of trees, the music's all synthesised, and it revolves around the question, "Who killed …?" (In Twin Peaks, it was "Who killed Laura Palmer?"; here, it's "Who killed Nanna Birk Larsen?") Oh, and like Twin Peaks, it's gloomy and foreboding. Unlike Twin Peaks, it's not weird. It's a fairly straightforward police procedural, albeit one that's plotted exquisitely, and unfolds at a sometimes funereal pace, daringly allowing the reality of the situation – the grief, the suspicion, the subterfuge, the domestic – to breathe in among all the clues and red herrings. The weirdness lies simply in the fact that it's all unfolding in Copenhagen. What a fascinating insight into another culture this is! And how much we are learning about the national character and the mechanics of local government and the best type of wood for a sauna (although, to be fair to Denmark, the character who's interested in the wood is Norwegian and having a house fitted out in Sweden – the subtle differences between, and cultural friction between, the three Scandinavian countries provides a lot of intrigue for we outsiders).

You may have picked up on the vital fact that the lead detective, DCI Sarah Lund (the mesmerisingly natural Sophie Grabøl), wears a Faroese jumper. In fact, she wears two, one white with a dark pattern, the other dark with a white pattern, a negative of the more famous one. It does speak of the show's essence, certainly you might wear one if you lived in cold, grey, wet Copenhagen, with thermals underneath, and in that sense it's key, and – as has been pointed out already – it's a rare flash of light in the seemingly permanent night of Denmark. But it's not all that matters. What matters is that, even though it's subtitled – and Danish is a really difficult language to follow, with very few Anglicised words (apart from, mainly, "alibi", "station" and "fucked") – you're gripped. We all know that subtitles are considered commercial poison. This is why even foreign films with a wide release in this country are trailed by trailers that feature no dialogue, just in case we spot that they're not in English! But BBC4 have bucked this trend. Firstly with Spiral – which I started watching but couldn't really fall in love with – and now this, which I could.

You're into a whole new strata of modest numbers once you leave behind the main five channels, but to have pulled in 600,000 viewers come the end of The Killing's run is a remarkable feat. Especially when the much less Danish and much more relentlessly marketed Mad Men drew nowhere near that amount to BBC4 in its last series, opening with 370,000. Hence its purchase by Sky Atlantic for the fifth. The Killing is a hit by anyone's standards. And it's all foreign. This is cheering news for non-philistines. (And in this matter, I speak as someone who was once subtitles-intolerant, but had that allergy massaged out of me about ten years ago.)

And can I just nominate Bjarne Henrikson as The Killing's finest performer, among many? He plays Nanna's bereaved removals-man father, Theis Birk Larsen, the Scandinavian Harry Secombe. Stoic and often wordless, this great bear of a patriarch conveys the whole paintbox of human emotion with those hooded blue eyes, blonde sideburns and tiny, expressive mouth. (Yes, he conveys emotion with his sideburns.)

Oh, and I haven't finished watching it yet – three more eps to go! – and for those here who have yet to even start it, let's steer well clear of whodidit spoilers, please. Tak!

July 15, 2011

Do not click on this picture

You will. But don't. I know this is my weekly notification that the new Guardian Telly Addict review is up, but I simply cannot embed it into my WordPress blog. (I know many of you understandably click on the picture every week, because I am monitoring you all 24 hours a day and know where you live, but you have been forewarned this week.) I'm reviewing the US version of The Killing on C4, The Night Watch on BBC2 and The Good Cook on BBC1, which is a new TV chef ruined by technological showing-off.

I hope you approve. The actual link is here.

(Apologies for heightened faff levels of comment moderation, but I'm getting a lot of grief at the moment.)

Boring

Hey, not to be too self-pitying about it, but the lead letter in the new Word magazine came from a disgruntled reader of the previous Word magazine, who went to the trouble of getting in touch with the magazine to declare that the piece I'd written for that issue about my experiences, aged 14-17, as a member of the Northampton College of Further Education Film Society, was "the most boring piece I've ever read in a magazine." Quite why this rude man went to the trouble of letting Word know is beyond me – as beyond me as why he continued reading when the first page, and the second, had bored him so much. Anyway, because Word do not republish online, I sought permission to reprint the piece, in full, here. It's very long. And it's very boring. Hope you like it! (If you don't, please stop reading at the exact point that you get bored. That's my advice.)

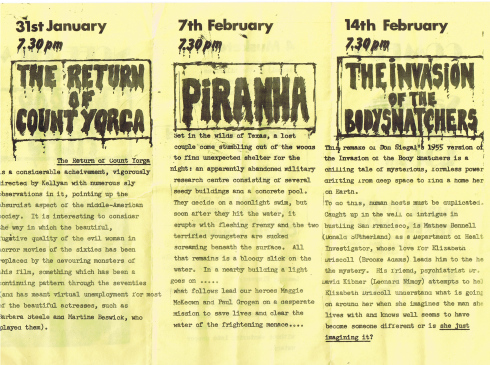

FIRST PERSON

In the early 80s, post-punk music and the cinema battled for my very soul

On Valentine's Day, 1980, a couple of weeks shy of my 15th birthday, I saw my first "X" film. The visceral Philip Kaufman remake of Invasion Of The Bodysnatchers, I didn't have to sneak in through a held-open fire door, wear a false moustache or lower my voice an octave, as per underage tradition. I paid £1 to see it, legally, projected onto a modest screen before an auditorium of arranged plastic chairs at Northampton College of Further Education's Arts Centre, courtesy of their members-only Film Society.

I loved it and wrote the following haiku-like review in my 1980 diary above a rough cartoon approximation of Donald Sutherland in his "footballer's perm" phase, emerging from an alien cocoon: "Really good'n'gory. Nice pod scenes, rather horrific, creepy and ace."

To contextualise this pivotal event in my junior filmgoer's life, in the same week in February 1980, my friend Pete and I had settled on the name D.D.T. for our first bedroom band (he on electric guitar; me on ice cream tub and tyre levers); and I'd optimistically posted off my entry for a Smash Hits competition asking readers to draw the 2 Tone label mascot Walt Jabsco as he might appear on the sleeve of another record (I had chosen The Damned's Smash It Up and neatly depicted him smashing up vinyl records) – the prize was a copy of The Specials LP.

Like any 14-year-old, I was wracked with a confusing hormonal need to fit in and rebel at the same time. My musical tendencies reflected this: I saw myself nominally as a "punk", although beyond a product-free sticking-up haircut that worried my Nan despite usually falling into a tame centre parting, I was just a provincial boy who wore sweatshirts and baseball boots from the Kay's catalogue and nothing more outwardly seditionary than the regulation Harrington jacket, which we all wore.

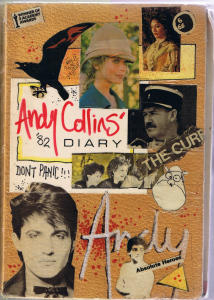

But a glance at the customised cover of my 1980 diary reveals a serious schism. Between the cut-out Photostats of my favourite bands the Undertones and 999 are pics of Gene Hackman, The Elephant Man and Marilyn Monroe, plus the logo of the aforementioned NCFE Film Society. At that difficult and easily distracted age, I was a little bit films and a little bit rock and roll.

I was not yet a member of the Film Society when I saw Invasion Of The Bodysnatchers – part of a special, leafleted Spring '80 Horror Films Season along with Piranha and The Return Of Count Yorga – but a guest of my friends Neil and Dave, a pair of what would these days be called nerds from the Trinity School side of town whom I'd fallen in with at Saturday morning art classes at "the Tech", and whose trendy English and Communications teacher Mr Tilley had been their link to the Film Society. Without perhaps fully appreciating it at the time, Neil (feather-cut, rainbow braces) and Dave (Phil Oakey fringe, green v-neck) were to be my passport into a new world and, ultimately, a fast-track to adulthood. That Film Club, as we knew it, would one day help qualify me for a career in film criticism would have been purely abstract at the time.

Northampton was, in the year of London Calling, one of the "faraway towns." Punk rock had only arrived there the year before, but I did my damnedest to catch up. My first official punk single had been Something Else by the Sex Pistols. (Rat Trap didn't count as it didn't have a picture sleeve.) Pocket money was thereafter invested in seven-inch vinyl futures; my broker was John Peel, whose late-nite Radio 1 show I was literally listening to under the covers through a single waxy earpiece. I remember in January 1980 going on an expedition to the still-new shopping mall in Weston Favell – colloquially known as the "Supacentre" – with my music-nut buddy Craig; after much deliberation, I bought the London Calling single, while he bought The Special AKA Live! EP. That evening the Undertones were featured on Nationwide, which felt like a moral victory for "us".

Craig lived in Weston Favell and so did my parallel pal Paul, who'd accompanied me to Invasion Of The Bodysnatchers. When I was round Craig's, we'd listen to music. When I was round Paul's, we'd draw cartoons together and pore over the movie spoofs in back issues of Mad magazine. Craig was into football, Paul couldn't even throw a ball straight when cast as a fielder in a school game of rounders; I was somewhere between the two.

It's clear to me now: between the years of 1979 and 1983 I was half-punk, half-nerd.

To neatly illustrate: in 1979 I'd begun to regularly buy two grown-up publications – the New Musical Express and Film Review. The former provided a vital weekly bulletin from the frontlines of the war on mediocrity, the latter a monthly fix of movie news albeit rather more vanilla in tone. An uncritical industry cheerleader for new releases, Film Review sold monthly through the ABC cinema chain. I expressed my devotion to it and to cinema in general by sending off for back issues, to study and keep, an early nod to voluntary history. I was now fully abreast of what was out, coming soon, and – less so in those days – in production. I had also become a devout disciple of Barry Norman and BBC1's Film '80, which morphed into Film '81, Film '82 and so on.

Paul and I expressed our groupie love of Barry one bored afternoon in 1981 – between drawing Mad-inspired caricatures of Charlton Heston and learning Monty Python LPs by rote – by improvising a silly, imagined clash of the titans, Barry Norman Vs Chris Kelly (ie. the presenter of ITV kids' movie magazine show Clapperboard). The cassette of this Pythonesque routine has been lost in time, fortunately, but it was definitely the Film Review me in ascendance, not the NME me.

When the two worlds collided, such as the week in December '79 when the NME devoted its cover story to a learned appreciation by Angus Mackinnon of Apocalypse Now, I felt whole. The rest of the time, I was torn. Was I about 999 and the Undertones, or Gene Hackman and The Elephant Man? Did I hang out with Neil and Dave and Paul, or Craig and Pete? The solution was: I hung out with both, separately.

Hey, I haven't even mentioned girls, whose sinister, preoccupying scent further complicated the hormonal tug-of-love in 1980: during the April and May of that year I started writing the name of my first actual girlfriend in every typeface I could passably render in a diary far more usefully employed as a logbook for films seen at the ABC and tunes heard on Peel.

In the final dark days before the VHS revolution, access to movies was controlled: you either saw a film at the cinema when the chains decreed it, or you saw it on TV after the usual five-or-six year gestation, and even then often cut for taste by the philistine broadcaster … unless you joined Film Club and transformed Tuesday nights for the best part of the academic year.

My 14-year-old desire to see Invasion Of The Bodysnatchers was salacious rather than academic: it was an "X" therefore I wanted to see what might be in it that qualified it to be one. (The "X" certificate seemed far more illicit than its prosaic replacement the "18".) My stunted height, choirboy's squawk and smooth features guaranteed I was among those fourth-formers who failed to get into The Exorcist and, a year later, Kentucky Fried Movie, even though on that occasion I was accompanied by my Dad, which cut no ice with the woman at the box office. But the NCFE Film Society, which I eagerly joined in September 1980, existed outside of such arbitrary, draconian restrictions.

First rule of Film Club: there were no rules. Actually, there was one: "All films start at 7.30pm – please try to be punctual." Once you'd paid your flat membership fee (£7.50, or £6 for students, OAPs and "claimants", which went up by a pound the following year), you were entitled to see all 36 films showing in the 1980-81 season and to sign in your own guests. A flash of your blue membership card also secured entry to and "unrestricted use" of the "Real Ale Bar" on film nights, where those of us at O-Level would comically nurse half-pints of shandy while making up nicknames for the more grown-up regulars. ("Stacy Keach," we called one of them, for self-evident reasons, keeping up the cineaste theme.) Film Club was run by a tireless man called Frank Quigg, who we must assume worked at the college. I have a picture in my mind of a slightly less racy History Man type with elbow patches but I may be post-rationalising.

During that first, mouth-watering season I saw any number of films that would have been off-menu if I'd continued to live the life of casual grazer: Roman Polanski's The Tenant (another "X", excitingly), Tomás Gutiérrez Alea's Memories of Underdevelopment (a landmark Cuban film set between the 1959 Revolution and the 1962 missile crisis with a prescient fractured narrative), Revenge Of The Creature in old-school red/green 3D, and the "lost" 1974 kitchen-sink drama Pressure, whose raw depiction of everyday life and separatist politics within the Trinidadian community in West London was quite a socio-political eye-opener. This was, I guess, the cinematic equivalent of roughage. Were it not for Frank Quigg, I might never have broadened my palate in this way.

It would be nigh-on impossible to explain the thrill of physical admission offered by Film Club to today's generation, spoiled as they are by push-button, palm-of-the-hand media access and the instantaneous sharing of opinion. You can download selected arthouse movies from the Curzon website the same day they are premiered on its cinema screens. If you favour less legal means, I expect the whole century of film is at your fingertips. In 1980, it was like we'd discovered a magic portal to another world.

By the time 1981 and phase two of Film Club's season had rolled around, a glance at my diary in February reveals a typically teenage list of "likes":

Digestives and butter and cheese

The B-side of Teardrop Explodes' Reward

Clint

Film Club

Playing snooker at Craig's

Lemon mousse

And a girl I'm not going to name

See how effortlessly films now slot into my 15-year-old spreadsheet? Focussing my teenage filmgoing devotion on Clint Eastwood was predictable; Paul and I had just seen a double bill, The Good, The Bad & The Ugly – "very ace indeed" – and The Outlaw Josey Wales – "Guns, guts and gob" – at Film Club so he was fresh and weatherbeaten-cool in our minds. But the tug of drumming along to Teardrop Explodes B-sides remained in place, not to mention the girl I wasn't going to name. (This meant she wouldn't go out with me.)

However, having paid my £6 I was still committed to squeezing my money's worth out of Film Club, and dutifully ticked off Summer Of '42 ("ace Durex-purchasing scene," according to my diary), Robert Altman curio Brewster McCloud ("a wonderful epic of weird and wit") and the first part of a Bill Douglas double, My Childhood ("black and white poverty-o plot") as the season built to its climax in April with Andrei Tarkovsky's meditative 1972 Russian sci-fi landmark Solaris ("bloody subtitles").

It would be easy to back-romanticise and rewrite my own underdevelopment so that Film Club's steady diet of foreign movies had a profound effect and opened my mind to world cinema on the spot. It didn't. Bloody subtitles indeed. I even fell asleep during the 165-minute Solaris, awoke and snuck out before the end. (Neil and Dave assured me that it got better after I'd gone.) But the fact remains, I was exposed to some choice nuggets of exotic cinema at an impressionable age, from Japan (Nagisa Oshima's Empire Of Passion) , France/Italy (Marco Ferreri's La Grande Bouffe), Germany (Werner Herzog's Nosferatu), and Argentina (Leopoldo Torre Nilsson's The House of the Angel) … I'd grown up with Abbot & Costello and British comedies like What A Whopper on TV, and James Bond and Disney at the pictures, so this forced march of maturity was significant.

But never mind the quality, feel the width. In 1981, I saw a total of 121 films. I have this precise figure at my fingertips because, world-class anal-retentive that I undoubtedly was, I had started keeping a running tally. This was the year that the Collins family took delivery of its first VCR – a Philips V2000 with the double-sided cassettes, very much the cleansed ethnic group in the VHS-Beta war – which eased the hunting of films around the TV schedules and empowered Paul and I to pause and replay the best bits of Chinatown, Death Wish, Deliverance and other choice, late-nite items from the ragged pages of the Radio and TV Times.

Within the year we would be supplementing our running cinematic buffet with those first trophies from video rental shops. At this nascent stage we'd bring home anything, frankly. And BBC2 were still lashing together Saturday night horror double bills, so you'd get 1943's The Seventh Victim followed by 1975's Race With The Devil. (Even on holiday in North Wales or the Channel Islands, we'd talk Mum and Dad into taking us to a local fleapit to catch the new Bond film: Live and Let Die in Nefyn, For Your Eyes Only in St Helier.)

If all this counting and collating suggests a quasi-autistic relationship with films, I can assure you that love coursed vividly through it. The badge of honour was in seeing every film I could possibly see. You can sense by the way each one is logged in my diary – title, year of release, certificate, followed by still frankly juvenile assessment ("Chariots Of Fire, 1981, 'A', starring Ian Charleston, Ben Cross … that's all the big stars out of the way!") – that I am now under the factfinding spell of the big film encyclopaedias I'd started buying or borrowing from the library.

I was taking a pocket-academic interest at last; starting to memorise years and directors' names like other boys reeled off the previous clubs and goal averages of First Division footballers. Key Christmas/birthday presents of the time included David Quinlan's Illustrated Directory of Film Stars and The Illustrated Encyclopedia of The World's Greatest Movie Stars and Their Films by Ken Wlaschin, which I pored over as if handling sacred scrolls. In particular, I fixated on filmographies of favourites like Gene Hackman, Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway and Charlton Heston, transported into reverie as I wondered what obscurities like Zandy's Bride, Psych-Out or I Never Sang For My Father might be about, or if I would ever see them.

Putting all such film studies aside, I still gleaned enormous, mathematical, savant-like satisfaction from the simple act of seeing multiple films in ad hoc double, triple or quadruple bills. During the Christmas holidays in 1981, for instance, I marked up six in one day, thanks to bingeing at the video with Bridge On The River Kwai, Carry On Doctor, Savage Bees, Superman, Superman II and Magic. At such a greedy rate, you can see how, the following year, my film total went up to 144.

In 1983, the year I turned 18 and cast aside the maroon blazer of the sixth form, I saw 175 films, which is I suspect a lifetime per annum record. Film Club, whose 1982-83 season was my last before heading off to London and to art college, helped plump up those impressive numbers. I never went to film school. But I didn't need to. Here, on tap, were the likes of Tony Garnett's directorial debut Prostitute, Luis Buñuel's Belle de Jour, further unsweetened black experience in Britain courtesy Babylon, Spielberg's 1941, the seminal Richard Pryor In Concert … but it is sad in retrospect to see Tuesday nights at Film Club gradually displaced by rented videos, band practices and nights at the Bold Dragoon pub.

I let my subscription to Film Club lapse without ceremony or fuss. Too many distractions. I carried on meticulously logging films in my 1983 diary, whose cover collage continues to convey my cultural duality by ranging Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now against Echo & The Bunnymen under sticky-back cellophane. I had carved up my soul and sold it piecemeal to post-punk raincoat music and Athena movie icons. My tastes in cinema had been converted to small-"c" catholicism by Film Club, and during the Christmas recess in 1983, I willingly sat down in front of the telly for my first Busby Berkeley musical, 1943's Take Me Out to the Ball Game and 1969's stunt parachutist drama The Gypsy Moths, mainly because I was on a mission to see the whole of Gene Hackman's CV.

I won my copy of the Specials LP in the Smash Hits competition in March 1980, by the way, and my drawing of Walt Jabsco was printed in the magazine. I was thrilled: an early taste of the media.

Before the decade was out, I saw my first ever professional film review – of the ho-hum yachting thriller Masquerade starring Rob Lowe – published in the NME, where I had found employment as a humble layout boy. From this en suite vantage point I had taken to pestering the paper's section editors for writing work, and they were starting to cave. Writing about music, and commissioning other people to write about music, dominated my nine-year employment history from 1988 to 1997 – NME to Vox to Select to Q – during which, videogames and live comedy made further supplementary claims on my time. But my devotion to films never waned.

In 1995, I briefly became the Editor of Empire magazine; in 2000, I landed the job of hosting Radio 4's weekly film programme Back Row; and, a year later, began writing about films for Radio Times, where I am still retained as Film Editor and – unbelievably – share reviewing duties with the source of my early film inspiration Barry Norman. I couldn't have achieved any of this without my self-enforced early-80s cinematic education, enhanced and nourished for those three key years by the imaginative and varied programmes of Frank Quigg, the geeky company of Neil, Dave and Paul, and the NCFE Film Society, where unrestricted use of the "Real Ale Bar" had made me a man, even without ever sampling any Real Ale.

And all this from a 16-year-old whose considered assessment of Buñuel's radical exposure of bourgeois sado-masochism Belle de Jour ran, in the 1982 diary: "This epic about horse carriages and bras was shit bum wank." And why not?

July 8, 2011

Watch the skies

OK, what would be called Telly Addict 10, if we were numbering them, which we're not, is up. (I kind of like waking up to it every Saturday, as it goes up around midnight which is past my bedtime. If you're interested, I usually watch it in the back of the BBC car that takes me in to be on Zoe Ball's programme on Radio 2 at 6.20am. With my headphones in, of course.) Under the hammer this week are FX's new sci-fi caper Falling Skies, BBC2′s Secrets Of The Pop Song, and Showtime's Nurse Jackie, now showing on Sky Atlantic, or, as it's known to most people, a future DVD box set. Sorry about the lack of shirt. I've been trying to keep my sartorial end up with a collar, but this week I stupidly went for a smart cardigan and t-shirt combination, and it was too hot in the studio to keep the cardigan on. Won't happen again.

July 4, 2011

Barking

You're all across The Tree Of Life, right? Sixth film in almost 40 years from Hollywood's most reclusive and slow-moving auteur Terrence Malick? The bloke who made Badlands, and then Days Of Heaven, and … yes, you could comfortably list all his films, although they're not exactly on TV every week. The Tree Of Life, which is sort of about a family in 1950s Waco, Texas, and the damage done to the eldest of three sons by a disciplinarian father, but is also about the meaning of life, and the wonders of creation, and nature versus grace, and the existence of God, or not (actually there's no "not" about it), and is so cleverly and deliberately designed to blow your mind, not all critics have succumbed and are calling it overlong and ponderous and even preachy and manipulative. Others, meanwhile, are calling it a masterpiece. It won the Palme d'Or at Cannes. It feels both European and American. It might be a masterpiece. It's certainly not a film that's been focus-grouped into submission – unless of course there was originally a cut that was even longer, and even more ponderous, and even more theologically manipulative.

If you've seen 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Darren Aronovsky's The Fountain, and The Lovely Bones, and the selected works of Jean Luc Godard – especially his more recent works – you're about halfway to getting the picture. Which is not my way of saying it's the kind of film you have to be a real smarty-pants to "get". You don't. The bulk of it is a fairly standard domestic drama in a period setting, with horseplay and tellings-off and tending to the lawn and dinner-table tension among the God-fearing. The bits where the origin of species and our potentially apocalyptic vanishing point are explored in mostly wordless, visually resplendent style, you choose how much to take from them. There would be nothing wrong with just sitting back and enjoying the pictures. They are amazing pictures – geological, astronomical, microscopic, biological, aerial, evolutionary - the sort you might see in an amazing documentary, except there they would be contextualised and narrated and stacked in some sort of order. Here, Malick uses these images – many of them pre-existing – to kind of wander off, deep in thought. The most protracted section comes within the first half-hour, just when you think you might be getting the measure of The Tree Of Life ("Oh, it's about Sean Penn, who's in the present, looked troubled, remembering his childhood in the 1950s – I get where we're going here, no matter how elliptically that's happening!"), and it's oddly jarring. But pleasurable.

I saw it this morning. It is quite an unusual way to start your Monday. I like being surprised. And I like being confused, to a degree. I like not quite knowing what's going on before my eyes. The dialogue is so minimal, with most of the wording coming through impressionistic fragments of whispered narration, that you're sometimes left scrabbling for detail. When a van drives through the neighbourhood spraying DDT and the kids dance about in the clouds of poison, you might ordinarly be expected to make a connection with this and, perhaps, a tragic event that we already know about. But it's not that straightforward. The image might just be an image. Malick is creating a whole here, not a series of easily-digested parts. It's how you feel at the end that counts.

Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain are well cast as the mum and dad, he all square-jawed and "Call me Sir" and ambitions thwarted but kept buttoned up beneath his starchy c0llars, and she all ethereal and saintly and pale, and Hunter McCracken is belieavable as the troubled adolescent tearaway, Jack, and these key performances (plus Sean Penn's in the modern day, existentially crushed by skyscrapers) give ballast to what might otherwise be a collage of snapshots and memories and bad dreams. I wonder if they knew what was going on?

I emerged, blinking, into the sunlight of Soho feeling oddly reassured and uplifted. And I don't believe in God. But it was that kind of experience, for me. I wouldn't argue that hard with anybody who emerged feeling like they'd been prodded in the chest, or led up the garden path, or had 139 minutes of their life taken away by an old sentimental man who has only made six films in 39 years. The Tree Of Life is not for all.

But it was for me.

July 2, 2011

Normal service

Telly Addict number nine is up on the Guardian website. (By the way, if anybody's clever and uses WordPress, would they have any idea why embed codes don't show up when I copy them into my blog entries?) This week, with my bloodshot right eye fading at last, I review my first ever episode of Top Gear on BBC2, and the opening episodes of HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce on Sky Atalantic and new comedy-drama Sirens on C4.

Incidentally, when I announced on Twitter that I was watching Top Gear for the first time (it has been going for 17 series since its stadium relaunch in 2002), a couple of very protective Top Gear fans informed me in a somewhat high-handed manner that I was not allowed to review a programme which I have never watched before. This was news to me. I objected to their objection. If I reviewed it and did not reveal that it was my first ever episode, then it might be a dereliction of critical duty, but since I make a point of it, I can't see the problem. (It's the first episode of a new series – my guess is that BBC2 would be delighted if some people started watching it.)

It's amazing how proprietorial fundamentalists can be. Anyway, you'll see that I have a certain amount of praise for the show, which is a big enough brand to juggernaut on for another 17 years without my patronage. Or until the oil runs out.

June 29, 2011

A personal explanation

It's a bit confusing. I posted this earlier, but felt it was too personal, on reflection, and removed it, so as not to add to what had turned into a bit of a deluge of goo. But, having taken down my bit, I also had to take down the comments, which seemed a bit harsh, on further reflection. So I'm putting it back up. But please don't post abusive comments, as many were doing. They won't be published, so you won't look clever in front of anybody. If you find this whole issue self-indulgent, then back away. Go and read something else.

Look at the two happy friends in the above picture. This was taken almost a year ago, and shows me (right) giving a birthday present to Richard Herring (left) on the Saturday closest to his birthday, in the 6 Music offices. We were at the 6 Music offices because, in July last year, we were almost six months into our stint in the Adam & Joe slot on Saturday mornings, having been booked for a month in February initially. What fun we had. The only downsides to the run that eventually lasted 13 months were a) not knowing how long it would last, which prevented us from ever feeling secure – and we were still billed as "in for Adam and Joe" months into our stint on the scrolling text on DAB radios and other electronic guides – and b) having to work around Richard's touring, and around Edinburgh, which took us both out of action for a month in August.

This week, as fans of the Collings & Herrin Podcast will know, we put out some "pretend podcasts" from November and December 2006, when Richard used to be a guest on my then-regular 6 Music weekend shows, and we would review the newspapers in a humorous and irreverent way. Listening to these recordings now – which were never podcasts, it's just a half-hour of radio with the music cut out for copyright reasons – it's amazing how young and silly and in love we sound! Little wonder that, a year after I stopped having a regular 6 Music show, we sought to recreate this exciting and natural chemistry by starting a podcast in Richard's house.

That was in February 2008, after a year of not doing anything together. At that time, I wasn't even being asked to deputise (or "dep") at 6 Music, as I had seemingly fallen out of favour with the station's bosses. Who needs them, I thought. So it was that Richard and I embarked upon our podcasting adventure, pretty soon falling into a rhythm of producing an hour of unedited, unscripted, unrehearsed nonsense every week, in his attic, using GarageBand and the in-built mic on my laptop. Collings & Herrin were born.

Over the next three years, we would not only keep this ridiculous podcast up, and pre-record podcasts to fill in the gaps when Richard was on tour or on holiday (I was seemingly never away), we also branched out into live performance, where our podcast relationship was made flesh for paying punters. The format stayed the same. But we changed. The podcast Richard became more and more dominant, and the 6 Music Andrew, the one who used to be in charge on the radio, became the butt of many of the podcast Richard's jokes and tirades. The irony was: in real life, we became closer.

When, in February last year, our podcasting reputation had finally earned us a shot at doing a radio show and we landed the prestigious Adam & Joe slot when Joe had to go off and make a hit movie, we were chuffed. Even though we were now equals, I knew how to "drive" the desk, so took charge of the buttons and faders. Also, Richard made no secret of the fact that he didn't much care about the music we were playing. This became part of our 6 Music schtick – we even built in a silly feature where I would "teach" Richard how to use the desk and he would press the wrong button (a rare example of something that was almost planned and rehearsed!) – and nobody seemed to object.

However, come the end of 2010, as if perhaps to compensate for the fact that I had my hands on the faders and Richard had never been given an email address, he grew more and more dominant on 6 Music, just as he had done on the podcast. The line between Herring and Herrin grew more blurred. I could see the comedy value in being the "victim", as, for most of the time, I knew I wasn't really the victim, and that most people who listened knew that. (Part of the real Richard, the one who is my friend, really does think I am an "idiot" but it's not the whole story, clearly.) I personally think we allowed the podcast relationship to infect the radio show, and by Christmas, it had changed.

Meanwhile, over the preceding year, I had become 6 Music's "super sub", filling in for pretty much any presenter who was ill, pregnant or on holiday. This was a development that I relished, as I love being on 6 Music on my own, and I love having the freedom to do other stuff while still being a "regular" on the network. I enjoyed doing the show with Richard on a Saturday, and with Michael Legge when Richard was gigging, but the solo shows were, and are, much less stressful. Richard delights in pushing the envelope, and always has done. This is even evident back in 2006, if you listen to the archive. It's what makes him brilliant and "edgy" (sorry to use a commissioning editor's buzzword) and vital. He is a unique professional comedian who occupies an increasingly enviable position in the comedy firmament: he plays by his own rules, plays to larger and larger audiences, and is now regularly invited on telly (despite his protests to the contrary). He works incredibly hard, and deserves every ounce of this success. I know he has moments of insecurity and doubt, but then, so do all comedians. It's a competitive business, and one that favours the young and the new, so to maintain a viable career by gigging and writing new material, and branching out, for 20 years or more is no mean feat.

Me? I had a stab at stand-up – ironically, because of the confidence that working with Richard had given me – but I am not deluded about it. I am not a comedian. I am a writer, and I am a broadcaster. These are the areas that might just continue to provide a career for me. Not comedy, or at least, not performance comedy. I envy Richard in many ways. His hard work is paying off. He is known as a pioneer in new media, and although I have had a hand in that, it's through AIOTM that he's made the biggest mark. I was never going to be a part of AIOTM – it was Richard's brainchild, and it was his project, and it would be separate to Collings & Herrin. I understood that.

I was, of course, the fictionalised butt of a lot of the jokes on AIOTM, and I think my discomfort at some of that is pretty well know, but Richard was respectful enough to pull back on that, and even invited me onto the stage, twice, to reclaim some dignity. I appreciated that. But AIOTM was Richard's thing, Richard's success, Richard's cult, Richard's Sony nomination. Just as Richard Herring's Objective is Richard's thing. And his Edinburgh shows are Richard's things. I have my things, which are, currently, a Guardian TV review, a slot on Zoe Ball's programme, and … yes, my regular solo work on 6 Music.

So, when 6 Music asked me to pilot a show with Josie Long, with a view to trying it out on air in July when Adam & Joe's latest bloc of shows ended, I was up for it. The writing had been on the wall for Collins & Herring on 6 Music from Christmas. We'd had a couple of run-ins, which we don't need to rake over, and all I can say is, I'm glad our last shows together on the network were less grumpy and shouty, and I think we ended on a good note. Which is why, understandably, many of our listeners, and podcast fans, are disappointed that Richard and I will not be filling in for Adam & Joe in July. Instead, it will be me, with another comedian. Josie and I have been given five Saturday shows, after which she, like everybody else in comedy, will be in Edinburgh.

Richard knows Josie better than me, although I have come to know her through the gigs that I have done for Robin Ince and Martin White. We are not forming a double act. We are co-hosting some shows, to see how they go. I think Josie will be great. I'm still kind of there to push the buttons and the faders. I appreciate that not all of our old listeners will like this change. But I hope they give Josie a chance. I don't need to be given a chance. I'm an old 6 Music war veteran in comparison to Josie. It's her moment, not mine.

So, Richard is cross that I have agreed to do a show on 6 Music without him, and with someone else. I respect him and his reasons for being cross. But I was not secretive about what was going on. And he knows that I rely on 6 Music now for a good chunk of my work. I have been a 6 Music presenter since 2002. I had a show on the first day ever of 6 Music. It was through my regular show that I was able to get Richard on, first on Roundtable, then as a regular guest. Our chemistry began to bubble up on 6 Music. But we both have separate careers, and always have had.

Richard is doing a run of solo podcasts in Edinburgh. Brilliant. I will download and listen to them all, and wish I was up there with him. But I can't afford the time or the money or the stress to go to Edinburgh. If I was going up, I feel sure we would be doing the podcasts together. But I am not a comedian, and I have no right to be up there. Also, the summer months offer up many "deps" at 6 Music, which, as I believe I have made clear, take priority. We're all self-employed; we all have to take our work where we can get it.

I love Richard Herring, in a funny sort of way. The penultimate time we saw each other was when we went to see Seinfeld – a great evening with my friend! I am sad that my decision to take a job without him has made him cross, and uncomfortable. But this is why the C&H podcast is on a break. We are on a break. I think, like a married couple, we will weather the break, and in fact, the break will do us good. We have both been working too hard.

I felt I should express my feelings about this before my first show with Josie, this Saturday, to clear the air. (Richard wrote about it on his blog yesterday, albeit more briefly than this.) I suspect Richard will not be listening on Saturday. But then, he claims not to listen to anything I do without him, or indeed listen to our podcast. He won't have listened to the "pretend podcasts" from 2006. If he did, I think he would be amazed how sunny and equal and silly we sound.

I hope we will be sunny and equal and silly again.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers